Poor diet quality is among the most pressing health challenges in the USA and worldwide, and is associated with major causes of morbidity and mortality including CVD, hypertension, type 2 diabetes and some types of cancer(1). The US National Prevention Strategy, released in June 2011, considers healthy eating a priority area and calls for increased access to healthy and affordable foods in communities(2).

High prices remain a formidable barrier for many people, especially those of low socio-economic status, to adopt a healthier diet(Reference Darmon and Drewnowski3). A 2004–2006 survey of major supermarket chains in Seattle found that foods in the bottom quintile of energy density cost on average $US 4·34 per 1000 kJ, compared with $US 0·42 per 1000 kJ for foods in the top quintile(Reference Monsivais and Drewnowski4). The large price differential between nutrient-rich, low-energy-dense foods such as fruits and vegetables and nutrient-poor, energy-dense foods might contribute to poor diet quality and various sociodemographic health disparities(Reference Monsivais and Drewnowski4–Reference Drewnowski7).

Increasing attention has been paid to the use of economic incentives in modifying individuals’ dietary behaviour. Fiscal policies (i.e. taxation, subsidies or direct pricing) to influence food prices ‘in ways that encourage healthy eating’ have been recommended by the WHO(8, 9). In September 2011, Hungary imposed a 10 forint (approximately $US 0·04) tax on packaged foods high in fat, sugar or salt(Reference Cheney10). One month later, Denmark implemented a tax of 16 Danish krone (approximately $US 2·80) per kilogram of saturated fat on domestic and imported foods with a saturated fat content exceeding 2·3 %(11). By 2009, thirty-three US states had levied sales taxes on sugar-sweetened soft drinks with an average tax rate of 5·2 %(Reference Brownell, Farley and Willett12). In addition, the Food, Conservation, and Energy Act of 2008 (Public Law H.R.6124, also known as the Farm Bill)(13) required a US Department of Agriculture pilot project to examine the effectiveness of a 30 % price discount on fruits, vegetables and other healthier foods in changing dietary behaviour among low-income residents enrolled in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program(14). Preliminary results may be available in 2013.

In the present study, we review current evidence from field interventions subsidizing healthier foods on their effectiveness in modifying dietary behaviour. A ‘field intervention’ refers to an experiment conducted in the real world rather than in the laboratory. The review focuses on the findings related to the following issues: Are subsidies effective in promoting healthier food purchases and consumption? What level of subsidies is required to be effective? Is there evidence of a dose–response relationship? Does the effectiveness differ across population subgroups? Are subsidies more or less effective than other intervention strategies? Does the impact maintain after the withdrawal of the incentive? Admittedly, it is unrealistic to address all these issues in a single review article as answers to those issues remain tentative, incomplete or even contradictory sometimes. Nevertheless, it serves as a starting point in the direction to synthesize relevant findings.

Four recent review articles are particularly relevant to our study. Kane et al. reviewed the role of economic incentives on a wide range of consumers’ preventive behaviours such as healthy diet, physical exercise and immunization(Reference Kane, Johnson and Town15). Wall et al. reviewed randomized controlled trials (RCT) that used monetary rewards to incentivize healthy eating and weight control(Reference Wall, Mhurchu and Blakely16). Thow et al. reviewed empirical and modelling studies on the effectiveness of subsidies and taxes levied on specific food items on consumption, body weight and chronic diseases(Reference Thow, Jan and Leeder17). Jensen et al. reviewed the effectiveness of economic incentives in modifying dietary behaviour among schoolchildren(Reference Jensen, Hartmann and de Mul18).

Our study contributes to the literature by systematically reviewing most recent scientific evidence on the effectiveness of monetary subsidies in promoting healthier food purchases and consumption. To synthesize data from a reasonably homogeneous body of literature with relatively rigorous study design, we exclusively focus on: (i) prospective field interventions with a clear experimental design; (ii) monetary subsidies in the form of a price discount or voucher for healthier foods; and (iii) food purchases and intake among adolescent and adult populations.

Methods

Study selection criteria

Studies which met all of the following criteria were included in the review: (i) intervention type: prospective field experiments; (ii) study population: adolescents 12–17 years old or adults 18 years and older; (iii) study design: RCT, cohort studies or pre–post studies; (iv) subsidy type: price discounts or vouchers for healthier foods; (v) outcome measure: food purchases or consumption; (vi) publication date: between 1 January 1990 and 1 May 2012; and (vii) language: articles written in English.

Arguably, children aged 11 years and younger comprise an important population for dietary intervention. Even so, we decided not to include them in the review for the following reasons. Children largely depend on their parents to pay their expenses. Therefore, most of the dietary interventions on children focus on free provision of a healthier meal or fruit/vegetable, nutrition education, role modelling and promotion of physical activities, while children-targeted interventions using a price discount or voucher worth a certain amount of money exchangeable for healthier foods remain scarce. Moreover, there has already been a systematic review on the effectiveness of economic incentives in modifying nutritional behaviour among schoolchildren by Jensen et al.(Reference Jensen, Hartmann and de Mul18).

Search strategy

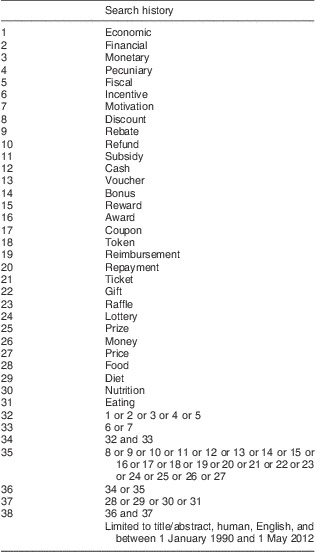

We searched five electronic bibliographic databases – Cochrane Library, EconLit, MEDLINE, PsycINFO and Web of Science – using various combinations of keywords such as ‘subsidy’, ‘discount’, ‘voucher’, ‘food’ and ‘diet’. A complete search algorithm for MEDLINE is reported in Table 1. Algorithms for other databases are either identical or sufficiently similar. Titles and abstracts of the articles identified through the keyword search strategy were screened against the study selection criteria. Potentially relevant articles were retrieved for evaluation of the full text.

Table 1 Search strategy for MEDLINE database

We also conducted a reference list search (i.e. backward search) and a cited reference search (i.e. forward search) from full-text articles meeting the study selection criteria. Articles identified through this process were further screened and evaluated using the same criteria. We repeated reference searches on all newly identified articles until no additional relevant article was found.

Data extraction and synthesis

A standardized data extraction form was used to collect the following methodological and outcome variables from each included study: intervention country, intervention duration, follow-up duration, intervention strategy, intervention setting, study design, economic incentive, eligible product, targeted population, targeted behaviour, sample size, outcome measure, study results and intervention effectiveness.

Ideally, a formal meta-analysis should be conducted to provide quantitative estimates of the effect of subsidies in promoting healthier diet. This requires intervention type and outcome measure across studies to be sufficiently homogeneous. However, among the twenty interventions included in the present review, few adopted the same experiment strategy and the type of food purchase/intake also differed substantially. The dissimilar nature of intervention strategy and outcome measure precludes meta-analysis. The present work was thus limited to a narrative review of the included studies with general themes summarized.

Study quality assessment

Following Wu et al.(Reference Wu, Cohen and Shi19), the quality of each study included in the review was assessed by the presence or absence of ten dichotomous criteria: (i) a control group was included; (ii) baseline characteristics between the control and intervention groups were similar; (iii) the intervention period was at least 5 weeks; (iv) the follow-up period was at least 3 weeks; (v) an objective measure of food purchases or intake was used; (vi) the measurement tool was shown to be reliable and valid in previously published studies; (vii) participants were randomly recruited with a response rate of 60 % or higher; (viii) attrition was analysed and determined not to differ significantly by respondents’ baseline characteristics between the control and intervention groups; (ix) potential confounders were properly controlled for in the analysis; and (x) intervention procedures were documented in detail in the article. A total study quality score ranging from 0 to 10 was obtained for each study by summing up these criteria. Quality scores helped measure the strength of the study evidence and were not used to determine the inclusion of studies.

Results

Study selection

A total of 8036 articles were identified in the keyword and reference search, among which 7963 were excluded in title/abstract screening. The remaining seventy-three articles were further evaluated in full text against the study selection criteria. Among them, thirteen were controlled laboratory experiments(Reference Epstein, Dearing and Handley20–Reference Giesen, Havermans and Nederkoorn24), computer simulations(Reference Waterlander, Steenhuis and de Boer25, Reference Waterlander, Steenhuis and de Boer26) or modelling exercises(Reference Cash, Sunding and Zilberman27–Reference Nordström and Thunström32) rather than field interventions; six exclusively enrolled children participants aged 11 years and younger(Reference Lowe, Horne and Tapper33–Reference Horne, Hardman and Lowe38); ten were cross-sectional observational studies without clear experimental or quasi-experimental designs(Reference Taren, Clark and Chernesky39–Reference Freedman, Bell and Collins48); seven provided fruits and vegetables in school or other settings for free rather than using a price discount or voucher(Reference Johnson, Beaudoin and Smith49–Reference Lachat, Verstraeten and De Meulenaer55); seven used economic incentives unrelated to healthier foods (i.e. financial rewards for weight loss(Reference Jeffery, Wing and Thorson56–Reference Jeffery and French60) or subsidies on staple or other basic food necessities(Reference Galal61, Reference Jensen and Miller62)); four used weight loss rather than food purchases or consumption as the outcome measure(Reference Wing, Jeffery and Pronk63–Reference John, Loewenstein and Troxel66); and two were published before 1990(Reference Cinciripini67, Reference Mayer, Brown and Heins68). Excluding the above articles yielded a final pool of twenty-four studies(Reference Jeffery, French and Raether69–Reference An, Patel and Segal92) with reported outcomes from twenty distinct field interventions. Figure 1 shows the study selection process.

Fig. 1 Flowchart showing the selection of studies included in the present review

Basic characteristics of the included studies

Table 2 summarizes the studies included in the review. The twenty interventions were conducted in seven countries: a majority of them (n 14) in the USA, and the remaining six in Canada, France, Germany, Netherlands, South Africa and the UK. Fourteen interventions provided price discounts for healthier food items, and the other six used vouchers worth a certain amount of money exchangeable for healthier foods. Subsidies (i.e. price discounts and vouchers) applied to various types of healthy foods and beverages sold in supermarkets (n 6), cafeterias (n 5), vending machines (n 5), farmers’ markets (n 2), restaurants (n 1) or organic food stores (n 1). Eligible foods mainly consisted of fruits/vegetables and low-fat snacks, and eligible beverages mainly consisted of fruit juice, vegetable soup and low-fat milk. Interventions enrolled different population subgroups such as school or university students, metropolitan transit workers and low-income women. RCT were the most common study design (n 9), followed by pre–post studies (n 8) and cohort studies (n 3). The difference between pre–post and cohort studies is that the latter not only had an intervention group as in the former but also a control group which was followed before and during the intervention.

Table 2a Summary of studies included in a review of field experiments on the effectiveness of subsidies in promoting healthy food purchases and consumption: intervention country, intervention duration, follow-up duration, study design, eligible item and intervention environment

RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Table 2b Summary of studies included in a review of field experiments on the effectiveness of subsidies in promoting healthy food purchases and consumption: targeted population, targeted behaviour, sample size/unit and intervention strategy

N/A, not applicable.

Table 2c Summary of studies included in a review of field experiments on the effectiveness of subsidies in promoting healthy food purchases and consumption: outcome measure, study results and intervention effectiveness

%E, percentage of energy.

Intervention effectiveness

All but one study found subsidies on healthier foods to significantly increase the purchase and consumption of promoted products. The only null finding, reported in Kristal et al., was likely due to its small financial incentive – a voucher worth $US 0·50 towards the purchase of any fruit or vegetable(Reference Kristal, Goldenhar and Muldoon73). As the authors noted in their conclusion, ‘more powerful interventions are probably necessary to induce shoppers to purchase and consume more fruits and vegetables’.

The level of subsidies varied substantially across interventions. The price discounts ranged from 10 % to 50 %, and the monetary values of vouchers were largely between $US 7·50 and $US 50, except for the $0·50 voucher in Kristal et al.(Reference Kristal, Goldenhar and Muldoon73). The lower bounds (i.e. 10 % price discount and $US 7·50 voucher) could serve as a conservative estimate for the minimal level of subsidies required to induce a meaningful increase in healthier food purchases or consumption.

There is some preliminary evidence from price discount interventions that the demands for fruits and low-fat snacks are price elastic – a 1 % decrease in price is associated with a larger than 1 % increase in quantity demanded. Jeffery et al. documented a twofold increase of fruit purchases in a university cafeteria when price was reduced by half(Reference Jeffery, French and Raether69). French et al. reported that the fruit sales in high-school cafeterias increased fourfold following a 50 % price reduction(Reference French, Story and Jeffery72). Lowe et al. reported an increase of fruit intake by about 30 % in hospital cafeterias when price was lowered by 15–25 %(Reference Lowe, Tappe and Butryn88). French et al. found a 50 % price reduction for low-fat snacks sold in university vending machines to be associated with a 78 % increase in sales(Reference French, Jeffery and Story71). French et al. reported a fourfold increase in sales of low-fat snacks sold in worksite vending machines when prices decreased by 50 %(Reference French, Hannan and Harnack86). Evidence for price elasticities of other foods is less consistent. For example, given a 50 % price reduction of salad sold in cafeterias, Jeffery et al. documented a twofold increase in sales(Reference Jeffery, French and Raether69) while French et al. reported none(Reference French, Story and Jeffery72).

Most studies adopted a fixed subsidy level that did not vary across groups or over time, so that the dose–response relationship could not be examined. Two exceptions were French et al. and An et al., which both confirmed a dose–response relationship between the level of price discount and sales/consumption of subsidized foods. In French et al., price reductions of 10 %, 25 % and 50 % on low-fat snacks sold in school and worksite vending machines were associated with an increase in sales by 9 %, 39 % and 93 %, respectively(Reference French, Jeffery and Story75). An et al. reported that 10 % and 25 % discounts on healthier food purchases were associated with an increase in daily fruit/vegetable intake by 0·38 and 0·64 servings, respectively(Reference An, Patel and Segal92).

Evidence on the differential effect of subsidies across different populations remains sparse. Blakely et al. is the only study that examined the differential effect of price discount on food purchases across ethnic and socio-economic groups(Reference Blakely, Ni Mhurchu and Jiang90). No variation in intervention effect was identified by household income or education, and the evidence for differential effects of price discounts across ethnicities was weak.

A few studies compared subsidies with alternative intervention strategies, namely nutrition education, product labelling, promotional signage (e.g. posters in cafeteria) and stimulation (i.e. a text message to remind/encourage action) or health message (i.e. a text message to introduce the health benefit of nutritious food intake). The results are largely inconclusive. Anderson et al.(Reference Anderson, Bybee and Brown74) and Bihan et al.(Reference Bihan, Castetbon and Mejean84, Reference Bihan, Mejean and Castetbon85) found that vouchers and nutrition education both increased fruit and vegetable consumption significantly (with similar effect sizes), and Anderson et al. reported that combination of the two had the largest effect. Conversely, Burr et al.(Reference Burr, Trembeth and Jones81), Ni Mhurchu et al.(Reference Ni Mhurchu, Blakely and Jiang89) and Blakely et al.(Reference Blakely, Ni Mhurchu and Jiang90) found no impact of nutrition education on fruit or other healthier food purchases. No effects on healthier food sales were found for health message(Reference Horgen and Brownell78), and some but limited effects were reported for product labelling(Reference Lowe, Tappe and Butryn88, Reference Kocken, Eeuwijk and Van Kesteren91), promotional signage(Reference French, Jeffery and Story75) and stimulation message(Reference Bamberg76).

Seven interventions included a follow-up period to assess changes in dietary behaviour after the withdrawal of incentives, but their findings diverged. Three found sustained improvement after the intervention – the effect remained the same in the 6-month follow-up reported in Herman et al.(Reference Herman, Harrison and Jenks79, Reference Herman, Harrison and Afifi80), increased by about twofold in the 5-week follow-up in Michels et al.(Reference Michels, Bloom and Riccardi82) and decreased by half in the 6-month follow-up in Ni Mhurchu et al.(Reference Ni Mhurchu, Blakely and Jiang89). Conversely, the other four interventions(Reference Jeffery, French and Raether69, Reference French, Jeffery and Story71, Reference French, Story and Jeffery72, Reference Lowe, Tappe and Butryn88) found no extended effect in the follow-up period.

Study quality

Table 3 reports the results of study quality assessment. On average, studies included in the review met six out of ten quality criteria, but the distribution of qualification differed substantially across criteria. Almost all studies included an objective measure of food purchases or intake, used a measurement tool that was shown to be reliable and valid in previously published studies, and documented intervention procedures in detail. In contrast, nearly none recruited participants randomly with a response rate of 60 % or higher.

Table 3 Quality assessment of studies included in a review of field experiments on the effectiveness of subsidies in promoting healthy food purchases and consumption

Note: Items 1 to 10 are all dichotomous variables.

Discussion

The high price of nutrient-rich, low-energy-dense foods relative to nutrient-poor, energy-dense foods might prevent individuals, especially those who have low income, from adopting a healthier diet. In the present study, we systematically reviewed evidence from field interventions on the effectiveness of monetary subsidies in promoting healthier food purchases and consumption. Improved affordability was associated with significant increases in the purchase and consumption of healthier foods.

Economic theory suggests that when the price of healthy diets drops, individuals will substitute healthy foods for unhealthy ones, but as their real income increases due to price reduction, they may spend more on food overall, including unhealthy foods. Among the interventions included in the present review, the amount of subsidies relative to personal income appears to be small. In this case, the income effect is unlikely to play a major role, and the study estimates suggest an unambiguous effect on improved patterns of healthier food purchases and consumption.

The evidence on the effectiveness of subsidies is to some extent compromised by a few major limitations in the reviewed studies. Arguably, the biggest limitation is the external validity of study outcomes. Almost all studies included in the review were limited in scale, had a small or convenience sample rather than a population-representative sample, and were implemented in very specific settings (e.g. one or a few supermarkets, cafeterias, vending machines, farmers’ markets or restaurants), which have substantially limited the generalizability of study results beyond the sample. Moreover, the intervention duration was usually limited to a few weeks and a majority of the studies did not incorporate a follow-up period after the intervention. Therefore, the long-term trends and effectiveness of subsidies cannot be evaluated and whether the effect will sustain after the withdrawal of incentive remains questionable. Separating the effects of subsidies from those of other intervention elements (e.g. prompting, product sampling, increasing the number of healthier food choices) was often infeasible due to the integrated study design. Policy makers are not well informed of the potential for large-scale application of subsidies on healthier foods because none of the reviewed studies explicitly measured cost-effectiveness of the interventions or evaluated the potential impact on the food industry. No study targeted overall diet quality and thus little is known about the impact of subsidies on total diet/energy intake.

In addition to weaknesses of the individual studies, the review itself also suffers from various limitations. Studies included in the review differed substantially by study population, intervention setting, experimental design and outcome measure, which precluded meta-analysis. Only a small proportion of the reviewed studies examined each predefined research question, resulting in a wide range of uncertainties. The literature search was restricted to peer-reviewed journal articles in English published between 1990 and 2012. Although this restriction may potentially increase the likelihood of obtaining concurrent studies with reasonably high quality, publication bias can be a concern. The review exclusively focused on one specific type of economic incentive, namely subsidies in the form of price discounts and vouchers for healthier food purchases, while other forms of economic incentives, such as taxes on less-healthy foods, food stamps for basic necessities or rewards for weight loss, were not examined. Readers interested in the role of taxation in modifying dietary behaviour may refer to the review articles by Caraher and Cowburn(Reference Caraher and Cowburn93), Kim and Kawachi(Reference Kim and Kawachi94) and Brownell et al.(Reference Brownell, Farley and Willett12).

The present study confirms findings on the effectiveness of economic incentives in modifying health behaviours from previous review articles. Kane et al.'s meta-analysis of forty-seven RCT estimated that the economic incentives, on average, worked 73 % of the time to improve consumers’ preventive health behaviours(Reference Kane, Johnson and Town15). All four RCT reviewed in Wall et al. documented a positive effect of monetary incentives on food purchases, food consumption or weight loss(Reference Wall, Mhurchu and Blakely16). Thow et al. reviewed twenty-four relevant studies and concluded that a substantial subsidy or tax on food was likely to influence consumption and improve health(Reference Thow, Jan and Leeder17). Jensen et al. reviewed evidence from thirty articles and found price incentives to be effective for altering children's food and beverage intake at school(Reference Jensen, Hartmann and de Mul18).

Despite the accumulated evidence on the effectiveness of economic incentives in modifying dietary behaviour, policy adoptions remain scarce. Hungary and Denmark are the only countries so far that have imposed a fat tax(Reference Cheney10, 11). In the USA, since the snack food tax in Maine and the District of Columbia was repealed in 2000 and 2001, respectively, no states currently levy taxes on snacks(Reference Kim and Kawachi94). Although a majority of US states have adopted a soft drink tax(Reference Brownell, Farley and Willett12), the tax rate is believed to be too small to induce a meaningful change in beverage consumption(Reference Sturm, Powell and Chriqui95), and no tax revenue is earmarked for subsidizing healthier food purchases or physical activity programmes(Reference Jacobson and Brownell96). Besides the opposition against targeted subsidies and taxation of foods from the food industry(Reference Caraher and Cowburn93), concerns on the unintended consequences of these policies may also contribute to the slow and reluctant adoption of economic incentives in improving diet quality(Reference Kim and Kawachi94). For example, a fat tax could be regressive for low-income populations who spend a higher proportion of income on food and consume more energy-dense foods. Although subsidies on low-fat foods are generally observed to increase sales and consumption of those products, improved health outcomes might not be achieved if higher consumption of low-fat foods leads to an increase in total energy intake.

Further research is warranted to advance knowledge about the role of subsidies and other economic incentives in modifying dietary behaviour. Based on the limitations of existing literature, future studies should aim to improve several aspects. A sufficiently large and representative sample should be used to obtain more precise estimates at the population level and facilitate subgroup comparison. More rigorous experimental designs, such as RCT, should be adopted to clearly demonstrate causal effects and prevent contamination of potential confounders. Overall food purchases and total diet/energy intake, in addition to that of the subsidized foods, need to be carefully documented to detect any unintended consequences. Finally, the experiment and follow-up periods need to be sufficiently long to assess the evolution and long-term effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the intervention.

Conclusions

Subsidizing healthier foods tends to be effective in modifying dietary behaviour. Even so, existing evidence is compromised due to various study limitations: the small and convenience samples of the interventions obscure the generalizability of study results; the absence of overall diet assessment questions the effectiveness in reducing total energy intake; the short intervention and follow-up durations do not allow assessment of long-term impact; and the lack of cost-effectiveness analysis precludes comparison across competing policy scenarios. Future studies are warranted to address those limitations and examine the long-term effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of economic incentives at the population level.

Acknowledgements

Source of funding: This study was funded by the National Cancer Institute (grant no. R21CA161287), the National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (grant no. R21HD071568), and the Anne and James Rothenberg Dissertation Award 2011–2012. Conflicts of interest: The author has no conflicts of interest relating to this manuscript. Acknowledgements: The author thanks Roland Sturm, Susanne Hempel, Roberta Shanman and Christina Huang for their helpful comments and generous assistance in study design and data acquisition.