Policy Significance Statement

The shift toward citizen-centric solutions in smart city development and urban data has reproduced top-down governance logics and failed to deliver inclusive democratic engagement and community empowerment in data governance. This research provides policymakers with a replicable and transferable participatory design process for the co-creation of data governance prototypes combined with multicriteria analysis to open up a plurality of perspectives on empowering community engagement without forcing participants to make trade-offs or settle on a single best option in the appraisal of complex knowledge and policy decisions. Design for social innovation and multicriteria mapping are put forward as a novel participatory methodological approach for empowering community engagement in urban data governance. This contribution addresses the lack of standard or consolidated methods to define data governance policies at a community level.

1. Introduction

Over the past decades cities and citizens have increasingly been equipped with sensors, devices, and platforms that capture data about urban flows and processes. Advocates such as technology vendors and urban managers have argued that this will greatly enhance the efficiency of urban governance, whereas critics have pointed to the challenges, for instance in terms of ethics and governmentality. Despite these debates, challenges remain in how to ensure urban communities are empowered to have their say over the ways in which they are involved in data governance. In the academic literature, data has been a prominent theme in urban scholarship exploring topics related to multistakeholder governance, community engagement and data rights in the context of smart city strategy (de Hoop et al., Reference de Hoop, Smith, Boon, Macrorie, Marvin, Raven, Jensen, Cashmore and Spaeth2018; Morozov and Bria, Reference Morozov and Bria2018; Yigitcanlar et al., Reference Yigitcanlar, Kamruzzaman, Foth, Sabatini-Marques, da Costa and Ioppolo2019). Investment in smart cities have sparked intense debates about the enclosing influence of the private sector in urban planning and critical infrastructure provision (Goodman and Powles, Reference Goodman and Powles2019; Carr and Hesse, Reference Carr and Hesse2020). Data communities are diverse and overlapping in scale, transcend binary categories (public vs. private) and do not map neatly across demographics, governance boundaries or applications. Implementing community engagement in more effective and inclusive ways remains an important and unsolved challenge in the digital strategy of every city. Questions remain about whether cities are equipped and capable of inclusive community engagement in relation to data governance in ways that will promote diversity, safeguard citizens’ privacy and accelerate sustainable urban transformation (Evans et al., Reference Evans, Karvonen, Luque-Ayala, Martin, McCormick, Raven and Palgan2019).

Data governance is an emerging field of study concerned with how a range of actors can successfully manage data assets according to rules of engagement, decision rights and accountabilities (Ladley, Reference Ladley2020, p. 17). Data governance raises various social, political, and ethical challenges for the community and institutions, especially in relation to power asymmetries between actors (Micheli et al., Reference Micheli, Ponti, Craglia and Berti Suman2020). Data’s role in society has been met with scepticism and uncertainty, particularly from the community’s perspective, on issues related to digital data collection, use and ownership (Kitchin, Reference Kitchin2016). Critical data studies scholars have pointed toward the instrumental use of smart technologies and algorithms as an emerging mode of “algocratic governance” which uses tracking, surveillance and social profiling to monetise experience, influence behavior, and intensify socio-economic discrimination (Pasquale, Reference Pasquale2015; Zuboff, Reference Zuboff2019; Sadowski, Reference Sadowski2020). These tensions highlight the need to balance individual and community autonomy in the use of data with the extractive nature of commercial business models and the drive for efficiency in public services (Veale, Reference Veale2018). Organizations face a variety of challenges related to operationalizing data governance. The governance of urban data can reproduce power asymmetries between institutions controlling urban data and other social groups and organizations excluded from decision-making (Lupi, Reference Lupi2019). Local governments have also encountered difficulties in carrying out data-driven social policy. Municipalities in Europe have used data to support the digital welfare state but experienced problems with data quality, privacy protections, citizen engagement, and democratic legitimacy (van Zoonen, Reference van Zoonen2020).

Our main research goal in this study is to develop and test a participatory methodology to identify strategies for pluralising community engagement in urban data governance processes. We ask the following research question: How can empowering approaches to community engagement in urban data governance be co-created and co-appraised by members of a precinct community? Given the empirical nature of our study, we are interested in data governance in the context of a university and technology precinct as an urban living lab that facilitates socio-technical experimentation across a range of sustainability related areas such as energy systems, mobility, and buildings. Our methodology utilizes design for social innovation to empower precinct citizens using enabling tools to support the development of data governance prototypes. Multicriteria mapping (MCM) is used to elicit diverse ways in which precinct citizens perceive community engagement in data governance by appraising the prototypes against a set of self-selected criteria. Using quantitative/qualitative web-based software and deliberation techniques focussing on opening up the appraisal process to participants equally, the method ensures systematic and equal attention is given across the prototypes and perspectives.

We trial this approach in the context of a revelatory case study of a university and technology precinct undergoing net zero transformation. The Net Zero Precincts (NZP) project is part of the Net Zero Initiative at Monash University, Australia, a $135 m initiative to become net zero carbon emissions by 2030.Footnote 1 “Precinct citizens” including university staff and students, local residents, and government and industry members were encouraged to participate in our study to co-create and co-appraise plural pathways at the precinct scale. We acknowledge that this participatory methodology has limitations in terms of the small number of “precinct citizens” engaged and the single instantiation of workshops and interviews. However, we contend that the insights to emerge from this empirical research makes a significant methodological contribution toward urban data governance studies.

This article is structured as follows: Section 1 provides a brief literature review of our conceptual framing that brings together urban studies, transition studies, and design for social innovation. This is followed by a section on our participatory research design and methodology. We then present and discuss results and insights from the empirical data collection that outlines future directions for research and end with a short conclusion.

2. Bridging Urban Studies, Transition Studies, and Design for Social Innovation

Our research is situated at the intersection of urban studies, transition studies, and design for social innovation. Critical urban studies scholarship has continued to demonstrate and criticize lack of community engagement in urban data governance projects, including in local sustainability initiatives (Paskaleva et al., Reference Paskaleva, Evans, Martin, Linjordet, Yang and Karvonen2017; Evans et al., Reference Evans, Karvonen, Luque-Ayala, Martin, McCormick, Raven and Palgan2019). The smart city vision has come under scrutiny for promoting a narrow form of “ICT-led urban growth” that fails to account for the specificities of distinct urban contexts (Barns, Reference Barns2018). Shelton and Lodato (Reference Shelton and Lodato2019, p. 35) argue that smart city endeavors are a vehicle for private sector actors to reinscribe “urban social and spatial inequalities” that privilege neoliberal forms of urban planning and governance. Smart living labs have also been criticized for utilizing top-down processes that preclude democratic engagement and promote a “technological fix” that can reduce the agency of community stakeholders (Levenda, Reference Levenda2018).

Urban scholarship also reveals a number of social, ethical, and technological challenges in operationalizing community engagement in data governance (Micheli et al., Reference Micheli, Ponti, Craglia and Berti Suman2020). These relate to tensions between corporate control and technological sovereignty (March and Ribera-Fumaz, Reference March and Ribera-Fumaz2018); privacy and data rights (Bennett and Raab, Reference Bennett and Raab2020); and top-down and bottom-up governance logics in a variety of institutional settings (Hodson et al., Reference Hodson, Evans and Schliwa2018). Smart city discourses that promote citizen empowerment have also been viewed skeptically as mere “window-dressing” to improve the appearance of profit-making systems of techno-surveillance (Cardullo, Reference Cardullo2020). Other urban scholars have argued for more inclusive forms of “entrepreneurial urban governance” that promote experimentation, multilevel governance and systemic learning across scales to foster social inclusion and resource efficiency (Swilling and Hajer, Reference Swilling and Hajer2017). However, few move beyond critique to unpack in more detail what community engagement in smart city development and data governance should look like.

Transition studies is an interdisciplinary field of scholarship, which posits that socio-technical systems like energy, transport and the built environment exhibit strong path-dependencies. Transition scholars argue that radical change is necessary because incremental change is insufficient to address sustainability challenges. According to this logic, systems-level transition is required to normalize far-reaching changes in institutions, infrastructures, markets, policies, behaviors, and culture (Markard et al., Reference Markard, Raven and Truffer2012). Transition Management is a particular governance framework within transition studies that suggests how various actors can be mobilized for sustainability to overcome path-dependencies and enable system-level transitions (Kemp et al., Reference Kemp, Loorbach and Rotmans2007). Similarly, Strategic Niche Management as a governance approach has emphasized the opportunities for creating protective spaces where new actor coalitions can articulare and share future expectations, experiment with alternative socio-technical configurations and generate and share lessons about their possibilities, limitations, and social desirability (Kemp et al., Reference Kemp, Schot and Hoogma1998). A relevant strength of transition inspired governance approaches such as Transition Management or Strategic Niche Management is that they use social learning processes to co-create futures with stakeholders by creating new socio-technical knowledge about current and possible alternative transition scenarios. This opens up new possibilities to think about the potential role of community members to anticipate and influence their own involvement in designing future socio-technical pathways.

Transition studies offer a conceptual understanding of incumbent socio-technical structures and process-based methods for engagement that are relevant to this study’s focus on pluralising approaches to urban data governance. Urban living labs for instance are urban arenas for designing, testing, and learning from emerging socio-technical experiments and practices with various actors in real-world settings (Bulkeley et al., Reference Bulkeley, Coenen, Frantzeskaki, Hartmann, Kronsell, Mai and Palgan2016; von Wirth et al., Reference Von Wirth, Fuenfschilling, Frantzeskaki and Coenen2019). Urban living labs are beginning to appear at precinct and related scales, such as a district or neighborhood (Sharp and Salter, Reference Sharp and Salter2017; Marvin et al., Reference Marvin, Bulkeley, Mai, McCormick and Palgan2018; Sharp and Raven, Reference Sharp and Raven2021). Critics, however, have suggested that transition studies overemphasis on systems underplays the role of actors and agency resulting in a gap so that the role of people is somewhat of an afterthought (de Haan and Rotmans, Reference De Haan and Rotmans2018, p. 275). Exceptions include the literature on actor (dis)empowerment in transition settings (Avelino, Reference Avelino2017) and the role of grassroots innovations in transformative change (Seyfang and Smith, Reference Seyfang and Smith2007).

Transition scholars have developed new analytical categories on smart city materialities, discourses, and institutions in the context of experimentation and institutional reconfiguration (Sengers et al., Reference Sengers, Späth and Raven2018). The complexity of sustainability transitions across a diverse set of sectoral and geographical contexts has also led to methodological innovations through the use of participatory tools to account for diverse group perspectives in evaluation processes (Raven et al., Reference Raven, Ghosh, Wieczorek, Stirling, Ghosh, Jolly and Sengers2017). From a socio-technical perspective, the realization of sustainability benefits in smart city development is by no means “automatic” and requires interdisciplinary, deliberative, and participatory processes that involve “prospective users” to improve the likelihood of implementation and ensure a diverse range of social perspectives are included (Nochta et al., Reference Nochta, Wan, Schooling and Parlikad2021, p. 264). The use of deliberate techniques, such as MCM, is increasingly recognized in studies of far-reaching and contested socio-technical change as an appropriate technique to improve the quality of and diversity within the governance of transitions (Truffer et al., Reference Truffer, Voß and Konrad2008; Eames and McDowall, Reference Eames and McDowall2010; Raven et al., Reference Raven, Ghosh, Wieczorek, Stirling, Ghosh, Jolly and Sengers2017). Nevertheless, while such approaches are strong in assessing diverse perspectives and improving debates about the future, what such approaches are lacking is a perspective on designing concrete ways forward for enrolling people into socio-technical futures.

Here, we contend that design for social innovation provides an agency-centered approach and participatory methodology that can open up community engagement in urban data governance and overcome some of the gaps identified in the urban studies and transitions literature. The technological focus of early design for sustainability research led to the emergence of design for social innovation with its focus on creating initiatives to address unmet needs by empowering community actors typically excluded from innovation systems, and to build capacity for these individuals and organizations to affect social change through new socio-material relationships in the interests of generating public good outcomes (Murray et al., Reference Murray, Caulier-Grice and Mulgan2010; Chick, Reference Chick2012; Ceschin and Gaziulusoy, Reference Ceschin and Gaziulusoy2016). Design for social innovation is a social learning process to catalyze socio-technical transformation through actions along a spectrum of diffuse design that can be undertaken by everyday people, to expert design carried out by professionals, or a hybrid of bottom-up and top-down approaches (Manzini, Reference Manzini2015, p. 40). Design for social innovation has taken insights from design thinking in product and service design and applied it toward fostering community-based and bottom-up innovations (Ceschin, Reference Ceschin2014). Design thinking has been part of the shift toward co-production in the public and social sectors and has been used to guide innovation that is more “experimental, iterative, concrete and citizen-centered” (Bason, Reference Bason2010, p. 174). As a social learning process, design for social innovation has applied design thinking to societal challenges through a large number of design experiments with citizens and institutions to enable learning-by-doing and transform innovation contexts (Rizzo et al., Reference Rizzo, Deserti and Cobanli2017, p. 4).

Design for social innovation is a form of social learning aimed at the “construction of socio-material assemblies for and with the participants” in projects (Manzini and Rizzo, Reference Manzini and Rizzo2011, p. 201). Examples include the Sustainable Everyday exhibition and City Eco Lab which demonstrated visions and scenarios of sustainable living using local community input (Manzini, Reference Manzini2015). Proponents share a people-centric view that supports active participation according to the idea that everyone is an “expert in what they do,” “has valuable insights,” and “a voice that needs to be heard” (Chick, Reference Chick2012, p. 55). Manzini developed the term “enabling experiment” to describe the creation of “favorable environments to enable local actors to take active roles as co-creators in the development and proliferation of social innovations” (Ceschin, Reference Ceschin2014, p. 4). This focus on individual and community empowerment uses design devices known as enabling tools that include prototyping as a catalyst for new actions and events (Ehn, Reference Ehn2008 cited in Manzini and Rizzo, Reference Manzini and Rizzo2011, p. 200). Enabling tools like prototyping make the ideas of everyday people visible, encourages emergent forms of collaboration, and uses experimentation to “put on stage” visions of future lifestyles and make them tangible (Manzini and Jégou, Reference Manzini and Jégou2003). Malmö Living Labs used prototyping to co-design “small-scale experiments in real-world contexts” with marginalized groups of people that were recognized as valuable “unused assets” (Hillgren, Reference Hillgren, Manzini and Staszowski2013, pp. 76–79). These participatory design-led local projects are conceived of as short-term, small-scale experiments that need to be amplified and nested within enabling platforms like urban living labs to achieve larger-scale transformation at a city-level (Manzini and Rizzo, Reference Manzini and Rizzo2011, p. 209). Within the context of design for social innovation, such experiments allow for new actors to enter through an open process of ideation and prototyping that create space for generative problems, opportunities and solutions to arise (Manzini and Rizzo, Reference Manzini and Rizzo2011, p. 211). This approach to nesting, scaling and generativity creates opportunities for transformative change through design-led learning processes that responds to the fluid and open-ended nature of urban experimentation (Raven et al., Reference Raven, Sengers, Spaeth, Xie, Cheshmehzangi and de Jong2019).

Geoff Mulan has pointed to visualization and a user-centered approach as strengths of design for social innovation but notes that weaknesses include a lack of implementation ability, the high-cost of design expertise and superficiality of some proposals (Hillgren et al., Reference Hillgren, Seravalli and Emilson2011). It has also been suggested that a singular focus on driving social innovations risks the omission of broader socio-technical structures and is unlikely to bring about the radical changes necessary for systems transformation (Ceschin and Gaziulusoy, Reference Ceschin and Gaziulusoy2016). Furthermore, design for social innovation interventions would benefit from deeper analysis from a transition studies lens especially in relation to the protection of spaces for niche innovation, key factors of success or failure and the roles of different actors in these processes (Ceschin, Reference Ceschin2014). We argue that drawing on combined insights from urban studies, transition studies and design for social innovation can provide a way to start thinking about a more comprehensive approach to the design of inclusive urban data governance processes in the context of the NZP. The next section details the participatory methods used to enable precinct citizens to ideate and evaluate relevant data governance prototypes.

3. Methodology

The choice of methods used in this study have been inspired by an ambition to situate the project within critical urban studies on smart cities, transition studies on urban transformation and design for social innovation. Overall, the methodological approach is informed by design for social innovation thinking (Manzini, Reference Manzini2015) and uses participatory design tools like prototyping as enabling processes that aim to empower people to make change happen in their local communities (Meroni, Reference Meroni2007). The result of design for social innovation processes can be products and services, principles, ideas, a social movement or a combination of these outputs (Chick, Reference Chick2012). We drew on critical urban geography research on smart cities for identifying cases of community engagement in data governance that were useful in framing the workshop to participants around themes of technological sovereignty and empowerment (Smith and Martin, Reference Smith and Martín2021). We chose MCM as the approach to evaluate the outcomes of the design process, based on insights from transition studies as well as critical urban studies concerned with opening up transition pathways to diverse views and interests, and supported by earlier successful application of this approach in the context of urban experimentation (Raven et al., Reference Raven, Ghosh, Wieczorek, Stirling, Ghosh, Jolly and Sengers2017).

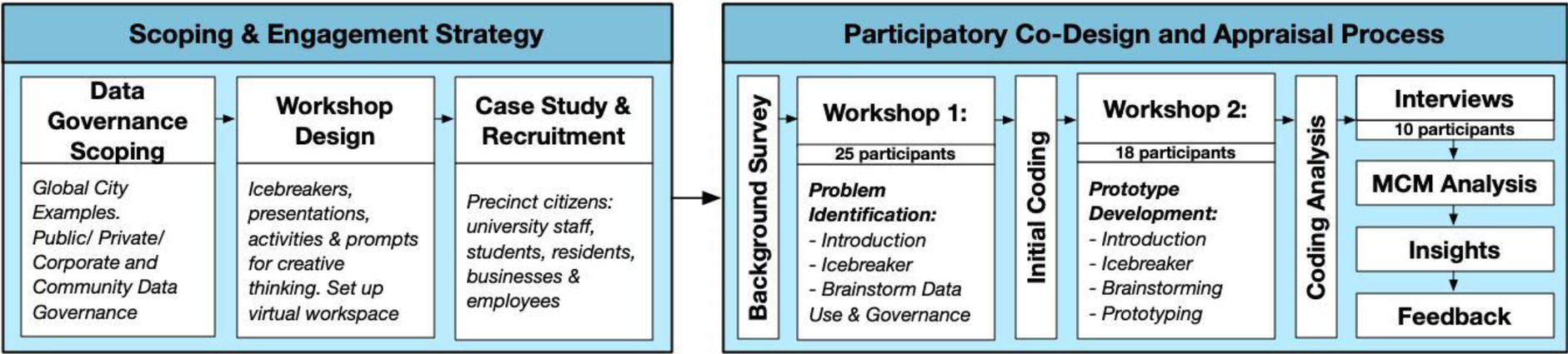

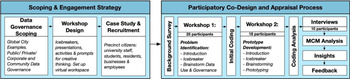

Hence, the methodological approach consisted of two overarching stages: (a) scoping and engagement strategy; and (b) participatory co-design and appraisal (Figure 1). The scoping and engagement phase involved a desktop review of global city examples of data governance approaches incorporating community engagement; workshop design drawn from the research team’s experience with design for social innovation and co-design methods; and recruitment of participants from the case study area. The second stage involved a series of primary data collection activities that began with short background surveys of participants to determine interest and familiarity with the topic. Two participatory co-design workshops were held: the first of which focussed on “problem identification” and invited precinct citizens’ to share their perceptions, practices, concerns, and uncertainties related to data governance. The second workshop focussed on “prototype development” with mostly the same cohort and used the co-design method to support small group ideation and rapid development of data governance prototypes. MCM interviews were undertaken with 10 workshop participants to evaluate the prototypes.

Figure 1. Project research methods: strategy and process.

3.1. Case study: Monash Net Zero Precincts

To address the research question and explore the usefulness of the methodology, we tested and refined the approach in a particular setting: Monash University’s Net Zero Precincts (NZP) project that forms part of the Net Zero Initiative which is operationalizing its main campus into an urban living lab focussed on precinct-scale decarbonization.Footnote 2 This initiative is developing within a diverse socio-institutional context, which presents fertile ground for trialing participation in data governance strategies between university, government, industry, and community members. The Monash NZP as such provides a revelatory case study for how to engage community participants in data-driven transformation pathways given the research team: “has an opportunity to observe and analyze a phenomenon previously inaccessible to social science inquiry” (Yin, Reference Yin2009, pp. 48–49). The Monash Net Zero Initiative is transforming all four university campuses to net zero carbon emissions by 2030, which relies on the use of data and digital techniques such as a microgrid, the equipment of buildings with sensors, data visualization platforms, and other technologies commonly explored as part of smart city projects (Evans et al., Reference Evans, Karvonen, Luque-Ayala, Martin, McCormick, Raven and Palgan2019). Monash University is the largest university in Australia with over 86,000 registered students in 2019.Footnote 3 The main university campus in Clayton, Victoria forms the research and education hub of the largest employment and innovation cluster, outside of the city center, within the Melbourne metropolitan area. Whilst decarbonization is an advanced topic and overarching goal at the campus, the NZP project is looking to expand its net zero transformation ambitions to the surrounding Monash Technology Precinct. This precinct is home to Australia’s national science agency and a host of innovative manufacturing enterprises including an emerging energy ecosystem. The technology precinct is interwoven with local residential areas, shops and small to medium enterprises.

3.2. Participant recruitment

Calls for participation were advertised widely to attract diverse Monash precinct citizens including university staff and students, local residents and businesses, government and industry members. The call was sent to NZP partners, government and industry contacts and advertised through Monash University public facing and internal media, and at the same time targeted communities with interest toward sustainable development. Residents were invited through an e-flyer sent to the City of Monash (local government) and publicly available community groups. A total of 25 participants attended the first workshop, with 18 participating in the second (17 of which had attended the first). Participants in the first workshop comprised 8 Monash university staff (both academic and professional), 11 students (undergraduate and postgraduate), 1 each from local government and the national science agency, and 4 local residents/small business. There were some overlap that a participant can belong to more than one category, for example, a student who lives in the precinct might have a different view compared to those who only study at Monash. Similar composition can be seen in the second workshop with five university staff, eight students, one each from local government and industry, and two local residents/small business. The participants had varied levels of familiarity and technical expertise regarding data governance based on results collected during the short background survey. Recruitment was focused on engaging precinct citizens that were interested in the creation, use or management of personal and collective data in the context of local sustainability. Overall the workshop participants, while small in overall numbers, reflected most precinct citizen groups the project aimed to include. We also acknowledge there was a higher proportion of university staff (professional and academic) and students (undergraduate and postgraduate) compared to other groups and reflect on this further in Section 5. We interviewed nine of these workshop participants in one-on-one MCM interviews (see Section 4.2).

3.3. Participatory engagement workshops

Design for social innovation uses participatory design methods called “enabling tools” to surface multiple perspectives to a topic or problem and explore solutions or new approaches using a variety of design tools, artifacts, and prototypes (Manzini, Reference Manzini2015). The co-design workshop is one such enabling tool that supports everyday people to generate, test and refine ideas using ideation and rapid prototyping (IDEO, 2015). Co-design workshops typically use story-telling scenarios or case studies as a grounding context for creative brainstorming, ideation, and prototyping. We held a series of two participatory engagement workshops to create inclusive learning environments for precinct citizens to discuss opportunities for mutual value creation and concerns about data collection, use and ownership, and start to understand diverse needs. The first workshop was run as two sessions on the same day to accommodate the large group size (25 participants) and ensure a balanced representation of diverse “precinct citizen” groups. Each had dedicated icebreaker activities to allow participants to get to know each other. All workshops took place in July 2020 during the Covid-19 pandemic which necessitated the use of online platforms. ZoomFootnote 4 was used as the main communications platform to deliver presentations and host break-out rooms. MiroFootnote 5 provided real-time collaboration capabilities using an online whiteboard environment for post-it notes, brainstorming and prototyping activities. All workshop activities were audio-visually recorded. While engagement could have diminished with online workshops, the use of preprepared Miro whiteboard activities coupled with the workshop activity design and dedicated facilitators per break-out group managed to encourage participation. Still, face-to-face workshops with its bidirectional communication and informal chat in between activities would have enhanced group interactions. Yet it is unlikely that this lack of informal interaction had any impact on the substance of results, due to the process-based structure of the design methods utilized and extensive preparation of the activity spaces in the online platform.

The first workshop introduced data as a critical asset in contemporary society and data governance as a process for managing value generation, control and collective good. Community engagement in data governance was presented through case studies on bicycle safety, urban ecology and emissions reductions. Participants were split into small break-out groups with at least one facilitator from the research team, and were invited to respond to a series of questions related to data use and data governance. Responses were added to post-it notes and placed on the virtual whiteboards. The whiteboard structure was developed to address the main research question and divided into four quadrants: (a) Perceptions (what we think happens); (b) Practices (what we currently do); (c) Expectations (how things should be); and (d) Uncertainties (what we want to know). The break-out groups went through two iterations of focused question and answer sessions adding post-it notes to the whiteboards with facilitators reporting key insights back to the group as a whole.

The second workshop used rapid prototyping which brings small teams together using creative media to develop a drawing, model or storyboard (Mulgan, Reference Mulgan2014). Prototypes are generally reviewed for desirability, feasibility and viability, with the most robust turned into pilot projects (IDEO, 2015). We recognize the contested nature of prototyping, which always happens within personal and situated conditions and histories, that set constraints on the possibilities of free and creative thinking. In terms of process, participants were introduced to a design challenge via three different story-based scenarios of data governance in the context of the research question. These stories were generalized into “how might we” questions, also known as opportunity statements. The workshop group was split into four break-out teams for a short brainstorming session, led by at least one facilitator, and were asked to come up with as many ideas as possible related to the opportunity statements. The final stage of the workshop involved a rapid prototyping session where teams selected top ideas from brainstorming and developed these into a tangible idea for a process, service, program, vision, tool or resource. Teams delivered a short presentation of their prototype back to the whole group.

3.3.1. Data analysis

We developed our analysis of results from the workshops using qualitative coding. Results from the workshops were collaboratively and iteratively coded and sorted within the Miro collaboration platform. For example, in workshop one, each team member worked independently to look for themes then discussed and consolidated themes as a team by looking at common themes and identifying any grouping that overlaps. Active categorization was used by drawing on insights from transition studies and urban experimentation to support data analysis and theory building (Grodal et al., Reference Grodal, Anteby and Holm2020). Our coding and data analysis was informed by Sengers et al.’s (Reference Sengers, Späth and Raven2018) conceptualization of smart city experimentation in the context of urban living labs which provided a useful analytic division between three categories: (a) the material arena which includes locations, physical infrastructures and technologies; (b) the discursive arena which describe visions, images and narratives of transformation; and (c) the institutional arena which reveals how governance arrangements are constituted between public, private, knowledge and community actors. The outcome of this process was four prototypes for community empowerment in data governance. These formed the basis for the next stage of data collection related to the participatory appraisal of the prototypes.

3.4. MCM interviews

MCM is a quantitative/qualitative evaluation method for exploring contrasting perspectives on uncertain, dynamic and contested issues (Stirling, Reference Stirling2010a). MCM helps individuals to explain their perspectives about complex issues in a structured and systematic way. Unlike other approaches to the social appraisal of technology that seek to “close down” the range of possible options, MCM invites participants to “open up” on the “plural and conditional” range of choices preferable under “different framing conditions” which relate to real-world divergence in contexts, values, perspectives and interests (Stirling, Reference Stirling2008, p. 280).

In this study, MCM interviews were undertaken with 10 precinct citizens between September and October 2020. Nine of these participants also had taken part in one or both of the previous two workshops. An energy industry partner also participated in an interview but was unable to attend the workshops. We aimed to be inclusive in our selection of participants to cover a diverse range of precinct citizen interests. The composition of interview participants was as follows: Monash University staff (one academic and four professional), postgraduate student (one), local resident (one), local government (one), energy industry partner (one), and national science agency (one). The MCM approach is supported by an online software tool to facilitate data collection, analysis and reporting.Footnote 6 Interview participants were emailed a briefing package in advance which provided an overview of the MCM process and the options (the four prototypes that were developed through the preceding workshops) to be evaluated in terms of addressing the “focal goal”: how can we empower community engagement in data governance for the NZP? At the start of the interview, participants were asked if they were happy for the Zoom call to be audio and video recorded and reminded they should conduct their appraisal in a personal capacity, bearing in mind their institutional context as a useful position from which to proceed with their responses.

MCM interviews followed a standard four stage process as prescribed in the manual: (a) review options; (b) define criteria; (c) assess scores; and (d) assign weights (Coburn et al., Reference Coburn, Stirling and Bone2019). In stage 1, the four core options (prototypes) were presented in relation to achieving the focal goal. Interviewees were asked to describe their general reaction to each of the options, identify any gaps and define their own additional option/s if the core options presented were considered insufficient. In stage 2, participants were asked to define self-selected criteria to evaluate the options from stage 1. Criteria are the different ideas, beliefs, technical judgements, or opinions participants might consider when evaluating each option. In stage 3, participants evaluated each option according to how well they thought it performed under each of the criteria defined in stage 2. In other words, the extent to which each option would achieve the focal goal under each criterion. This involved scoring each option according to each criterion—giving both a pessimistic and optimistic score (between 0 and 100)—reflecting the subjective values of the interviewees and taking into account uncertainties that may arise when assessing the different options. In stage 4, respondents were asked to assign weights to the criteria to reflect their overall priorities. This was aided by a visual representation of the scores and weights to see the implications for how options end up being ranked compared to each other. At each stage, participants were asked to explain their reasoning so that the researcher could take qualitative notes of the reasoning underpinning the quantitative assessment. At each stage, the researcher asked the interviewee to confirm that he/she was comfortable with the pattern of scores on the charts and if it provided a reasonable reflection of their own judgements. If not, readjustments in the assessment were made accordingly until the results were in line with the interviewee’s judgment.

3.4.1. Data analysis

Results from the interviews were analyzed using the MCM online software tool following the protocols defined in the MCM manual (Coburn et al., Reference Coburn, Stirling and Bone2019). In summary, quantitative and qualitative data were examined together within the online tool and both played an important role in forming conclusions. The qualitative MCM data comprised three forms: the options (the four prototypes) presented to participants for appraisal; statements made by participants during the interview and recorded by the researcher as text notes; and recordings of discussions during the interview (audio-visual recordings were captured in Zoom). The quantitative MCM data was structured using the online tool and comprised four forms: numerical values for pessimistic and optimistic scores for the options under particular criteria; the intervals between these scores which constitute the range of uncertainty associated with the options under particular criteria; the weight (relative priority) of each criteria as determined by individual participants; and the ranks computed by the software tool to express the overall performance of each option (prototype) under all criteria on the whole. It is important to note that as a hybrid method MCM aims to focus as much attention on the qualitative reasoning of participants (discursive and textual) as to the numbers derived from scoring (graphical representation). We analyzed the process around two sets of results namely (a) performance diversity: relative performance observable across all prototypes on empowering community engagement; and (b) appraisal diversity: how different participants use diverse criteria for assessing each prototype’s capacity to empower community engagement (Raven et al., Reference Raven, Ghosh, Wieczorek, Stirling, Ghosh, Jolly and Sengers2017).

4. Results and Findings

This section presents results and findings from the two workshops and 10 MCM interviews held between July and October 2020.

4.1. Workshop one: Problem identification

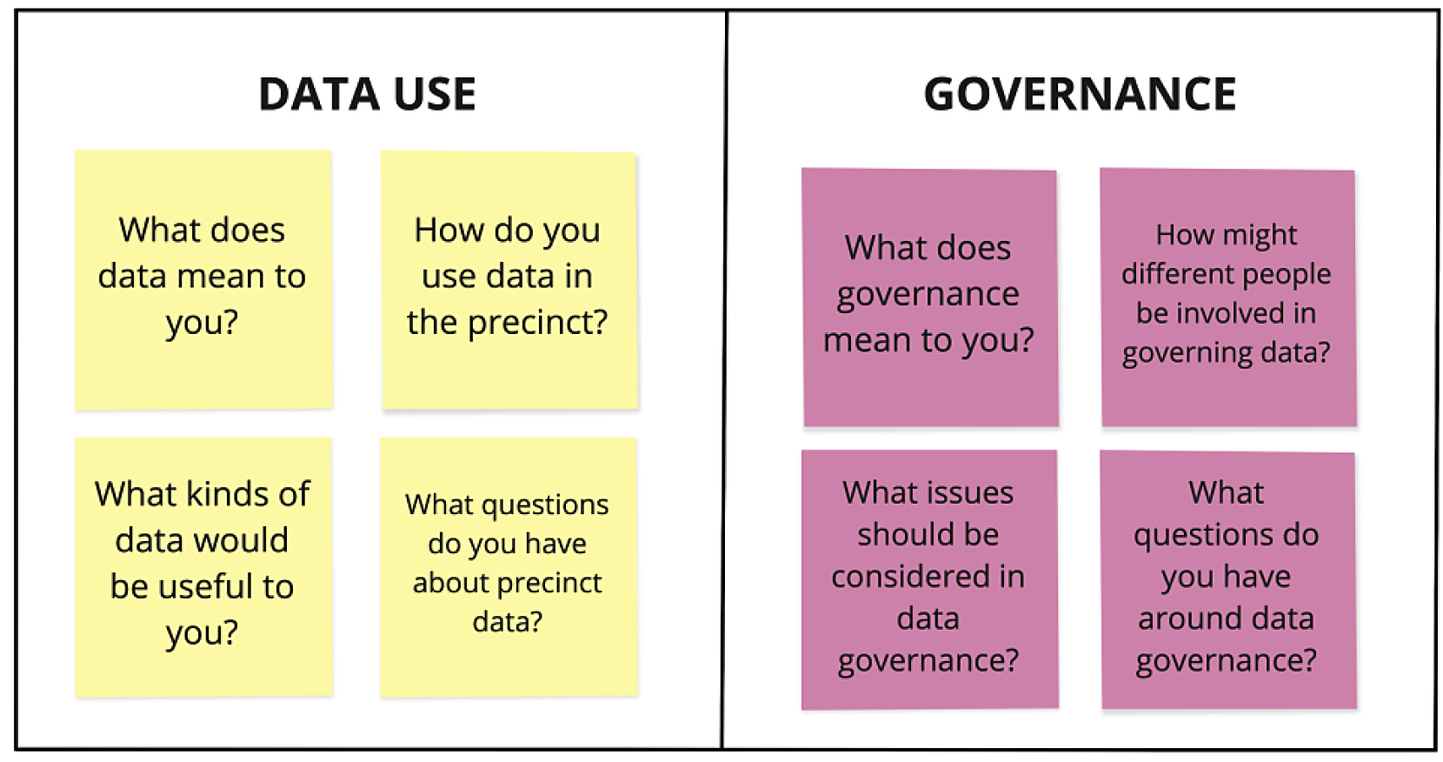

The Problem Identification Workshop (workshop one) invited participants to reflect on and discuss data use and data governance in small break-out groups using virtual post-it notes to capture ideas. Across the two sessions there were four break-out groups, each with dedicated facilitators from the research team to answer any questions and provide additional guidance to encourage open discussion and promote diversity of views. Participants were given time to individually respond (on post-its notes) to the four questions relating to “data use” starting with “What does data mean to you?” (on yellow post-its, see Figure 2). The participants then discussed the topics and placed their post-its on the four quadrants of their group’s whiteboard containing the four titles: Perceptions, Practices, Expectations, and Uncertainties (as shown in Figure 3). A second activity followed answering four different questions (see Figure 2) related to data governance, starting “What does governance mean to you?” but using different colored (pink) post-its to distinguish these responses from those from the first activity. Participants were again invited to place their post-it note answers on to the four quadrants of the whiteboard. Each of the eight questions are shown in Figure 2. Figure 3 shows one of the four break-out group whiteboards at the end of workshop one.

Figure 2. Workshop one: eight questions relating to data use and data governance.

Figure 3. Workshop one: four quadrant whiteboard during post-it note ideation activity.

During both activities group conversations took place in Zoom, while participants were writing and placing virtual post-it notes in Miro. Toward the end of this activity, we identified that there were substantially more pink post-it notes on the “Expectations” and “Uncertainties” quadrants compared to yellow post-it notes (as shown in Figure 3). This suggested that participants had many expectations about data governance, but at the same time were highly uncertain about data governance issues. After the workshop, we reviewed the recordings of each individual break-out group session. Following this, we combined the four break-out group whiteboards and grouped the post-it notes by common themes. This was performed by all researchers involved in facilitating break-out group discussions to minimize the risks of misinterpretation of the outputs. Overall, the results from the first workshop revealed three clusters of themes—data, values and processes—that were informed by Sengers et al.’s (Reference Sengers, Späth and Raven2018) analytical categories of materiality, discourses, and institutions in smart city experimentation.

4.1.1. Citizen data

The first cluster of ideas revolved around citizen data. Participants identified data interpretations and literacy as an expectation of what data governance should consider. With the growing amount of data it is important for citizens to be aware of available data sets and able to make informed decisions on their use. Another theme within the cluster is access and interfaces. Access as articulated in the workshop includes actual access to data, different levels of access, better indices and data discovery. Intuitiveness and readability were identified as part of data interfaces. Ensuring high levels of security and protection were also conveyed. This includes expectations on transparency on how citizen data will be protected and the handling of sensitive and personal data. The need for standards and best practices emerged from collections of ideas. Participant conversations revealed a general lack of awareness of available structures for data governance and processes particularly in relation to data formats. Examples of participants’ remarks on the Miro board include: “Energy bills, comparing my energy use with others;” “Some organisations are collecting my information;” “Open data set structure and format;” “Who owns the data? security and privacy issues.”

4.1.2. Citizen values

The second cluster of ideas includes diversity, equity and inclusion, democratization and decentralization, trust and transparency, quality and integrity. Diversity is one of the most prominent themes within this cluster. The need to consider different languages in metadata and equity in data access are some of the expectations identified by participants but at the same time there were concerns about bias in data processing, particularly with the use of algorithmic technology. Data democratization was identified as another expectation in which participants conveyed various ways citizens can be involved in data governance including ability to vote on data related policies and issues as well as through mechanisms like Creative Commons licenses. Participants also expressed a general lack of transparency in dealing with data and that a good governance should include means of communicating how citizen data is collected, managed and used. This was put forward as a way to build citizens’ trust in entities who will be managing data. Additional ideas within this cluster included data quality and integrity and a proposal to incorporate peer review processes to maintain data integrity. Examples of participants’ remarks include: “Information about me, others can make money with;” “I get to vote on policies of data procurement, management and access;” “Can we trust them?” “Who put you in charge?”

4.1.3. Citizen processes

The third cluster of ideas relates to consultation and communications, roles and responsibilities, and agency. Conversations and notes in the session revealed aspects of, in this case, NZP community coordination and how community participants can have their own advocate or champions (selected as community representatives) that would act as a conduit or connect them to precinct institutions like the university and local council. Ensuring that proposed data governance has gone through a review process and providing opportunities for community feedback were suggested. However, issues of hierarchy within communities and how it can impede citizens from expressing ideas freely was noted. Questions were raised about who collected data, who is in control, and stewardship (who is responsible for various data). Thus, it was identified that there is a need for clear responsibility and roles in data governance design. Participants also envisaged that strengthening individual and community agency over data creation and use is crucial in fostering meaningful citizen engagement toward governance. Examples of participants’ remarks include: “Local ratings and reviews;” “Someone is responsible for managing my data;” “Providing opportunity for community feedback;” “Locus of responsibility, if something goes wrong, who’s responsible?”

4.2. Workshop two: Prototype development

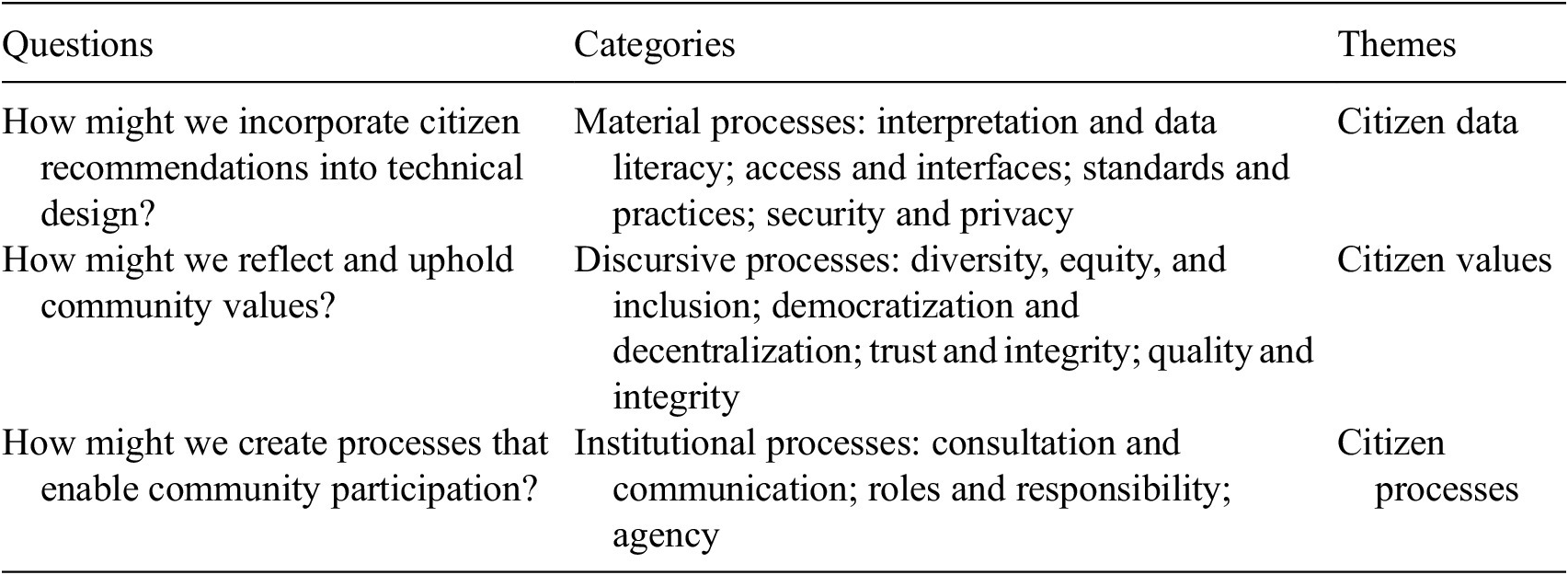

The second workshop shared back results from the previous workshop and used this as the basis to develop the following opportunity statements called “how might we” questions which were used to stimulate a brainstorming session in small break-out groups (Table 1). Participants were then asked to select their favorite ideas from the brainstorming boards using a red-dot based voting system to simplify the selection process (Figure 4).

Table 1. “How Might We” questions, categories, and themes

Figure 4. Workshop two: idea selection for prototyping (colored dots represent participant votes).

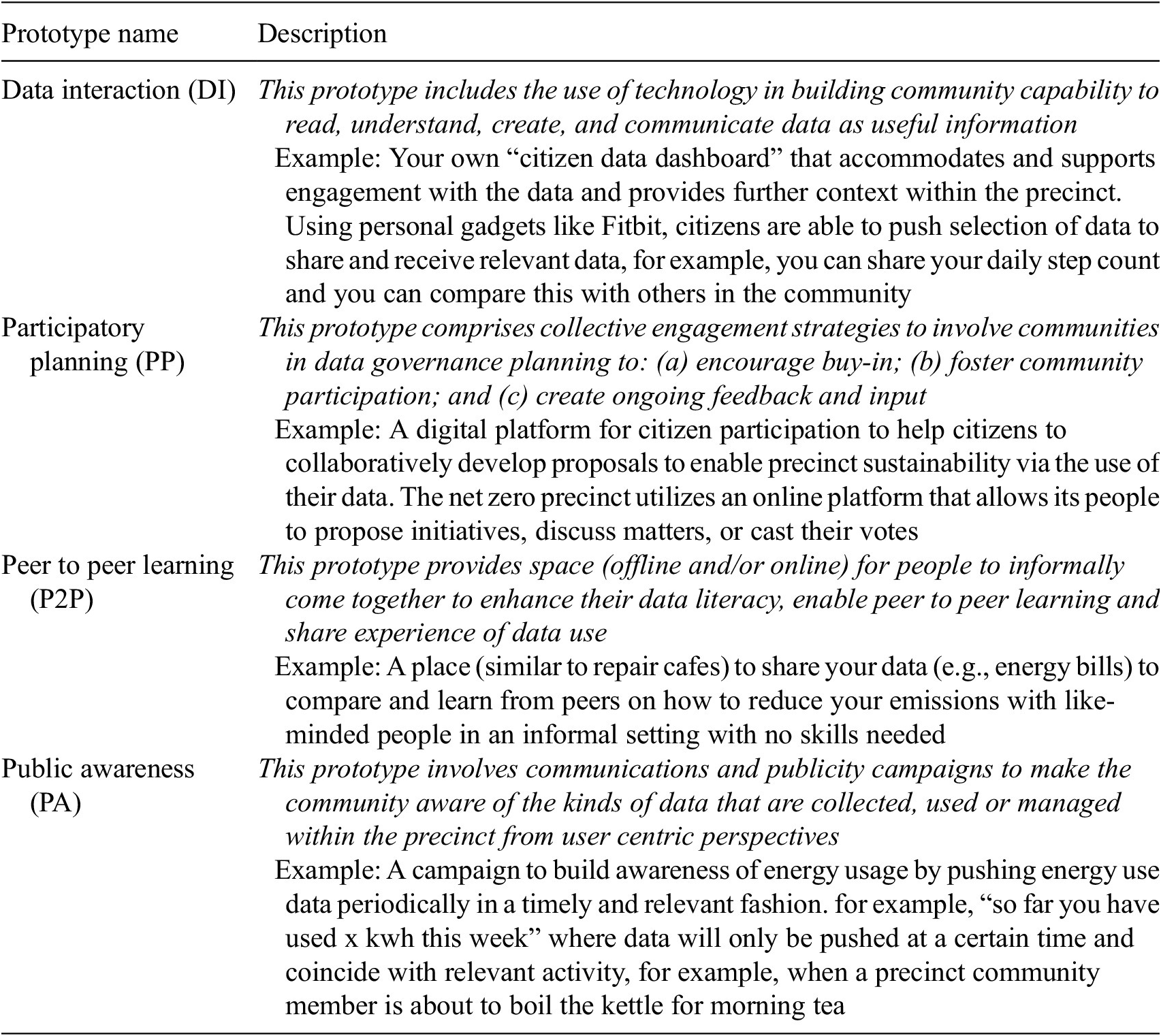

Teams were given 30 min to develop a basic prototype using the following guidelines: (a) select ideas based on either the most feasible, the most innovative or one that provides greatest benefit to the precinct community; (b) design something tangible: for example, a process, service, program, vision, tool, or resource; and (c) identify its purpose, function, and users. The four prototypes are summarized below (Table 2).

Table 2. Data governance prototypes from co-design workshop two

4.3. MCM interviews

The four data governance prototypes developed during the second workshop were presented as core options for empowering community engagement in the MCM interviews with 10 participants (P1–P10). The participants appraised these prototypes against their self-defined criteria. This section will outline performance diversity and appraisal diversity (see Section 3.4) of the results from the MCM process.

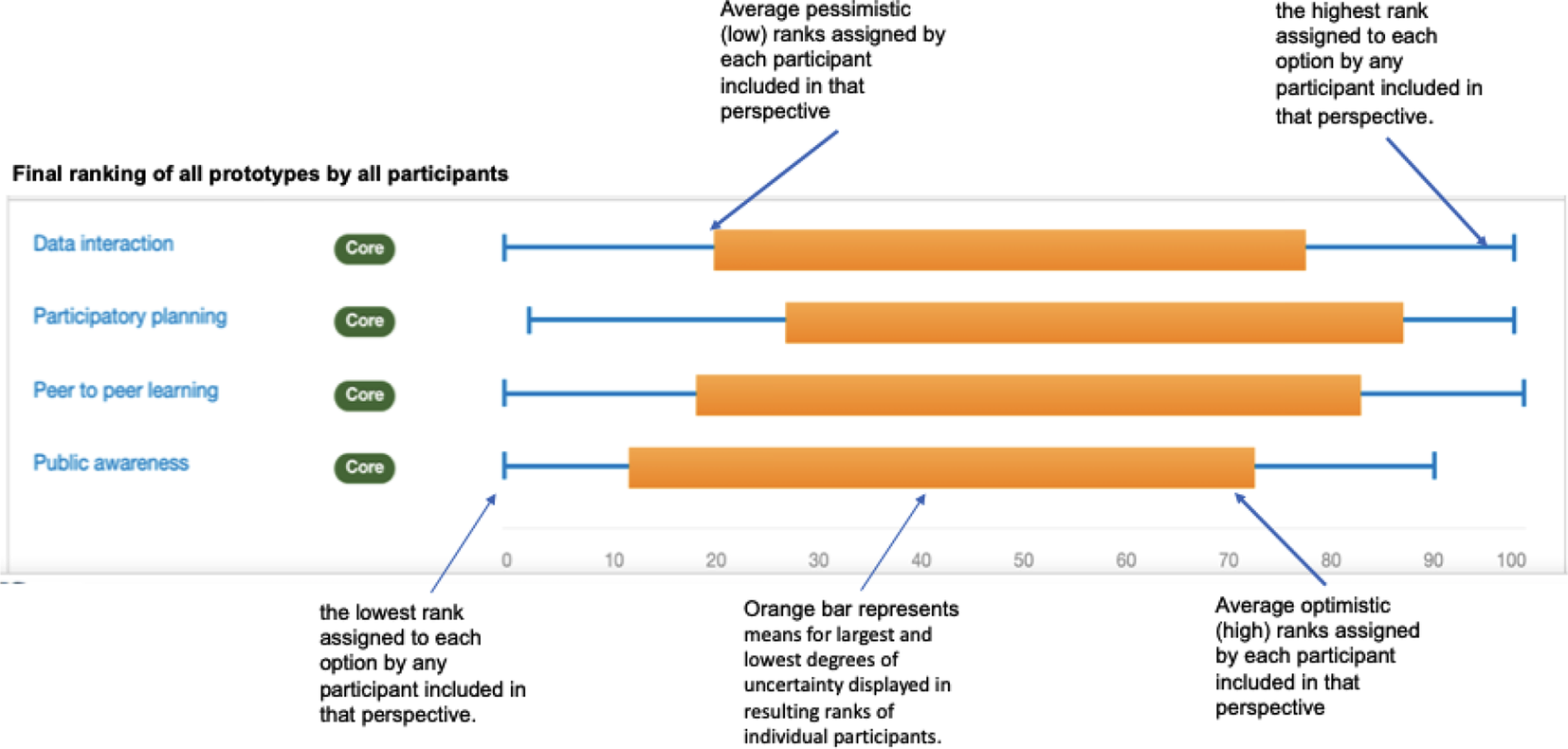

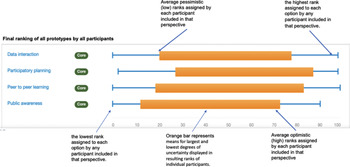

4.3.1. Performance diversity

Performance diversity relates to the observable differences in the assessments for each of the prototypes (known as options in MCM) in the overall capacity to empower community engagement. The overall ranking of the four prototypes based on the aggregated appraisals of all individual participants is shown in Figure 5. The MCM interviews revealed that both participatory planning (PP) and peer to peer learning tend to be perceived as having greater capacity to empower community engagement than the data interaction (DI) and public awareness prototypes. However, all prototypes received a more or less similar ranking which shows that these approaches are all considered desirable in terms of empowering community engagement. The range of scoring indicated by the orange bars shows a combined effect of uncertainty, conditionality and variability in the assessment of the prototypes. The overall ranges are very broad for all prototypes, showing relatively high optimistic and low pessimistic scoring.

Figure 5. Performance diversity of prototypes (options).

The wide range of uncertainty indicated by the orange bars reveals that participants perceived performance of the prototypes as conditional on a diverse range of factors (Figure 5). The data shown in Figure 5 is not an attempt to make a rigorous statistical analysis, but rather as a qualitative indication of the uncertainties. Analysis of the qualitative data from the MCM interviews sheds light on the conditional evaluation of the prototypes, articulated by participants through a range of strengths, weaknesses and challenges, thus opening up the evaluation process to a plurality of approaches rather than building consensus on a definitive solution.

The plural, uncertain and conditional assessment of the prototypes revealed a number of insights. Engaging the community through the DI prototype was seen as having potential to provide a wide range of data-driven insights but requiring more care to avoid the misuse of data. One participant suggested that this prototype might appeal to early adopters only and potentially exclude those who are not comfortable with technology: “How do you capture people who are not aware about the technology? If exclusive, it could backfire the benefit of the program” (P2). This prototype was also judged as better able to address individual empowerment but with added data sharing could promote collective achievements that might incentivize behavior change. DI was viewed as a powerful option to see the impact of having data on people (P9). The option will benefit from the use of data visualization but that “data interpretation needs to be easy and not overwhelming” (P9).

The PP prototype was seen by some participants as having the potential to provide a voice to citizens, something beyond the approach of feedback requests in conventional community consultation processes. PP was also considered to provide a sense of agency in planning and decision-making processes which could result in longer term buy-in. However, participants also observed there could be some challenges in running PP processes related to inclusivity and the specific focus on topics to be deliberated. For example, some participants suggested this prototype might require people to be preengaged in the topic to be involved and thus exclude those who are not active in the knowledge space or only attract established community leaders (P7). Interview participants suggested that any PP approach should have a well-defined agenda on intended programs to enable more focused community feedback. To quote one university staff member: “It is useful to have these platforms but sometimes if you have too much of a blank slate it may be too hard for people to conceptualize or get enough of a cross-section” (P9). It was also suggested that a PP process should not be exclusively online and have an accompanying in-person element like a focus group (P1). In this option, data will be useful if utilized to show implications of decisions being made at the planning stage as suggested by (P10).

The peer to peer learning (P2P) prototype was seen as a uniquely powerful approach for driving change at the grassroots level. The ability to access knowledge from other peers was seen as attractive to people who are not actively involved in the knowledge space of using data for sustainability and want to get up to speed. Participants that were supportive of a peer to peer approach to community engagement offered various justifications including the ability to keep the momentum going and making sure that knowledge sharing continues organically. Suggestions to improve the prototype included linking knowledge transfer to an outcome and/or to include experts in the conversation. Another participant observed that this prototype requires people to meet together in a certain “space” which could pose challenges for people who are reluctant to meet in person. To address this, it was suggested that the activities could be designed within an already active community or network, for example, library, cafe or food court where people are already visiting. Another suggestion was that the prototype could be augmented by an online component to provide more flexible engagement and make it more attractive for people to join any time as stated by a Monash Council employee: “pre smartphone/internet, it would be a meet up at some place which I might not go but with a Whatsapp group I do not miss out on anything that I deem important: it is flexible engagement, free and accessible” (P7).

The public awareness (PA) prototype, while having potential to reach many people, was seen as problematic in terms of its unidirectional information flow which does not provide opportunities for feedback from the community. This prototype was also considered lacking in a call to action for behavior change. Involving community representatives from diverse backgrounds was also viewed as very important for any future public awareness campaign/s. Interview participants suggested that the public awareness prototype should attempt to include those who have not been involved or interested about data use and emissions reduction initiatives by involving community champions and public figures and leveraging social media influencers. Participants also suggested that public awareness required the community to have a base level of awareness on the benefits of data use for driving emissions reduction within the NZP.

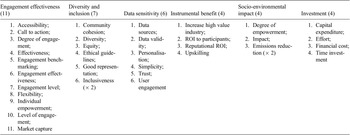

4.3.2. Appraisal diversity

Interview participants’ contrasting judgements and perspectives can be defined as appraisal diversity (Raven et al., Reference Raven, Ghosh, Wieczorek, Stirling, Ghosh, Jolly and Sengers2017) and analyzed at an individual or aggregated level to reflect the full range of relevant issues (Coburn et al., Reference Coburn, Stirling and Bone2019). Differing perspectives on empowering community engagement were reflected in participants’ selection of criteria and how these criteria were weighted. By weighting the criteria, participants expressed their own judgment concerning the relative importance of the different criteria.

In MCM analysis, appraisal diversity can be identified by experimenting with different ways of grouping the various types of data collected and critically reviewing any relevant patterns or clusters of ideas that emerge. This qualitative clustering resulted in two types of groupings: (a) perspectives: groupings of different types of participants that were involved in the appraisal; and (b) issues: groupings of different types of criteria used by participants to appraise the options (Coburn et al., Reference Coburn, Stirling and Bone2019). Observing any patterns emerging from these groupings allows for a more detailed understanding of participants’ views of the prototypes (options) from a diverse range of perspectives.

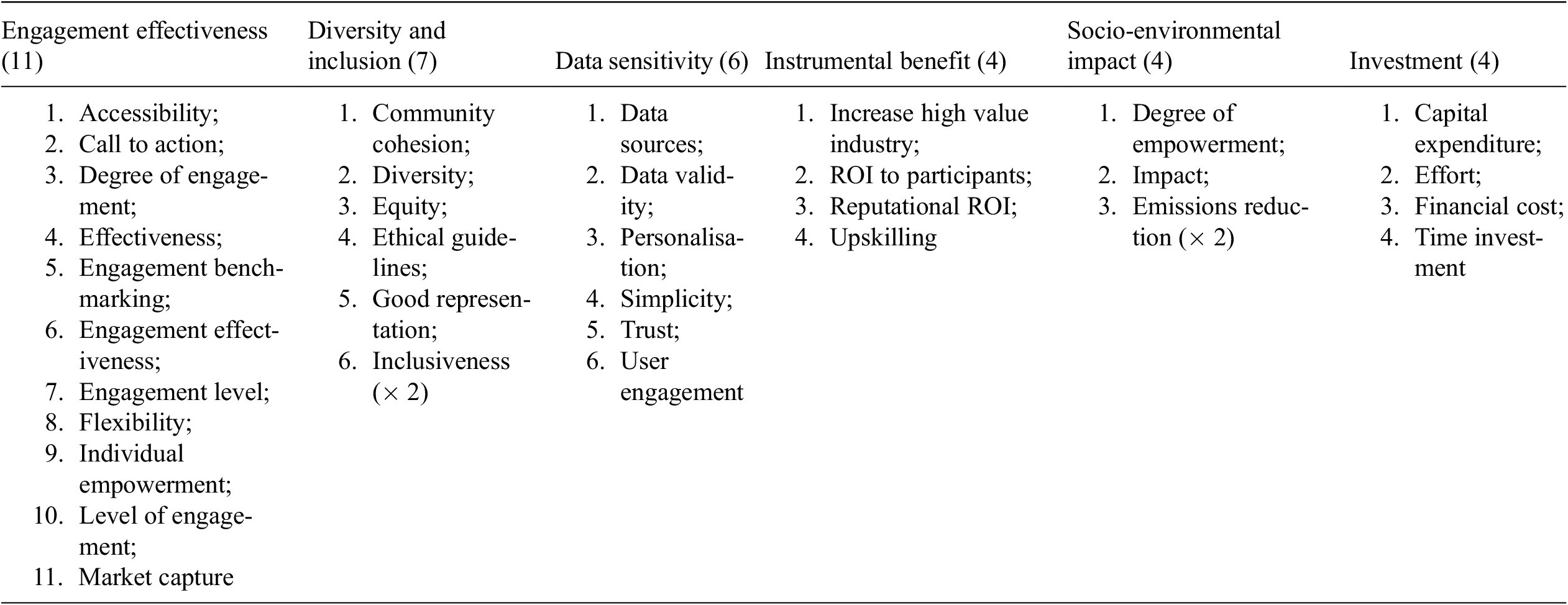

A total of 36 criteria were proposed by the participants—an average of four per participant. The different criteria selected by each participant reflected a diversity of perspectives and value judgements. Criterion with the same name can have different meanings and emphasis depending on each participant’s interpretation. For example, inclusiveness was defined by one participant as the extent to which a prototype is inclusive of diverse groups of people, while another participant perceived inclusiveness as how well the prototypes can attract people who are usually excluded from sustainability conversations—those beyond the “usual suspects.” All 36 criteria were grouped by the research team into six issues through grounded analysis of the participants’ subjective definitions (see Table 3).

Table 3. Summary of issues (grouped criteria)

Engagement effectiveness which accounted for the most criteria (11) proposed by participants included criteria that considers the number of people that will engage; the extent to whether they will stay with the program; barriers to participation; and also how empowered citizens would be to participate. For example, the criteria of flexibility is included in this issue as it was defined as “flexibility in being able to participate at an individual’s own pace and capacity” (P8). This criterion was proposed by a student participant who needs to juggle study, work, self-development and other interests and that her participation in any event is often determined by time availability and ease of access to places. The diversity and equity issue include criteria that point to the cohesiveness and diversity of community representatives from different cultures, backgrounds, and interests. A notable criterion in this group is community cohesion which refers to “the degree to which individuals feel they are part of and supported by the community” (P1) which went a step further to consider the collective empowerment in engagement initiatives. Data sensitivity on the other hand was expressed as how data is utilized in the program; appropriate use of data; and how relatable the data is to community members. Participants who included criteria of appropriate use of data. An interesting criterion named user engagement was included to evaluate which options result in the greatest use of data available. Here participant (P10) specifically linked their appraisal to the data governance issue.

Instrumental benefit refers not only to the value of the program to community members including upskilling and networking but also to the university and industry partners (e.g., increase high value industry). One participant who proposed the criteria of ROI to participants focussed on the potential benefits of the prototypes to them personally: “what are intangible benefits for me e.g., networking, career, growth opportunities, personal branding etc.” (P5). The set of issues under “socio-environmental impact” considered the degree to which the four prototypes could encourage behavior change and initiatives toward emissions reduction and net zero transitions. This issue also includes a degree of empowerment criteria which refers to “how much people feel their participation and input has brought about any changes” (P4). Finally, the investment issue reflected participants’ criteria around time, financial and opportunity costs associated with each of the prototypes.

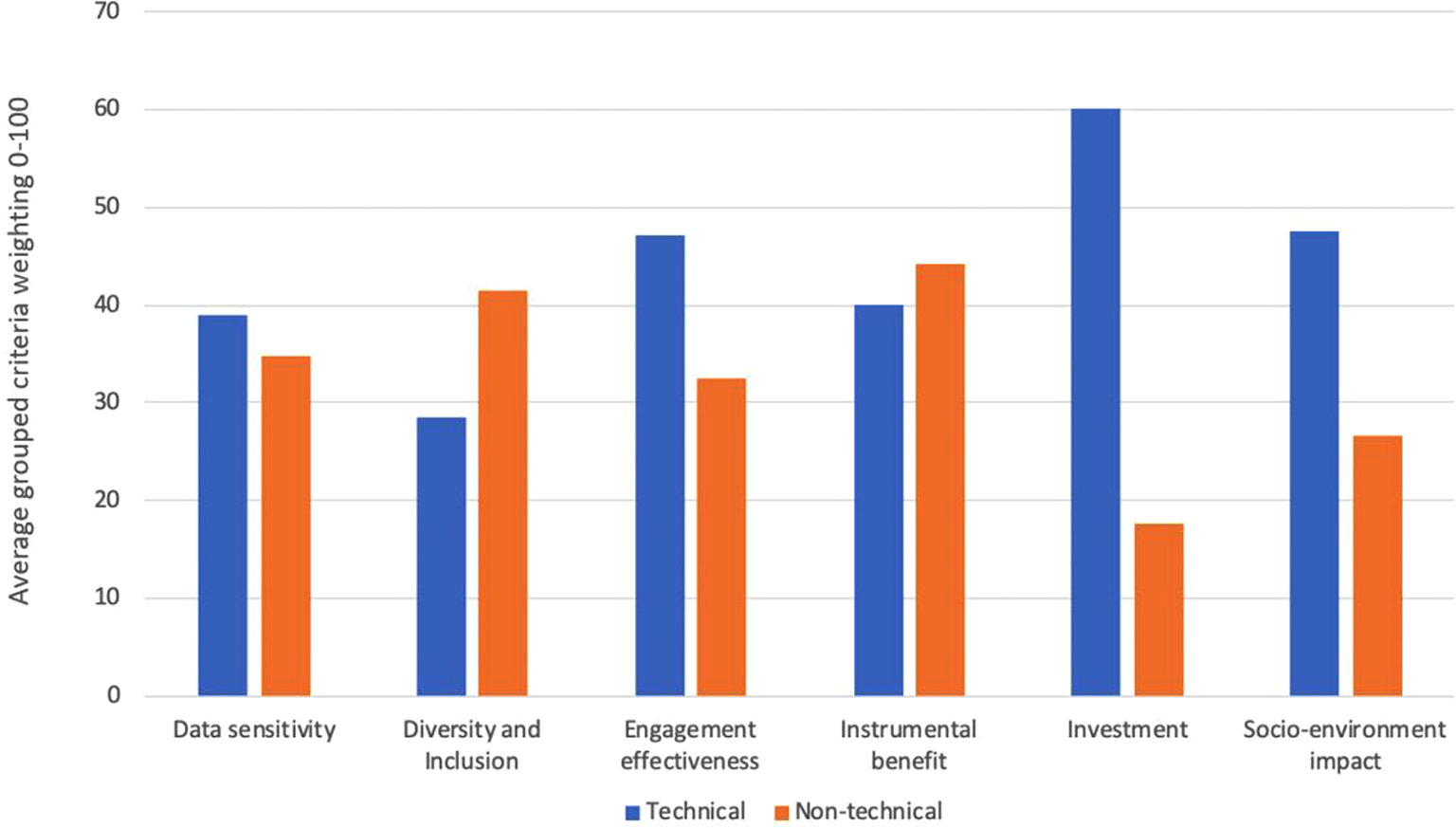

As an example of capturing appraisal diversity at a semi-aggregated level, we compared the weights assigned to each group of criteria under participants’ perspectives across those identified with “technical” and “non-technical” background (Figure 6). Data is conventionally perceived as a technical consideration yet data governance issues affect a diverse range of stakeholders including those from non-technical backgrounds. The MCM participants were grouped into the two perspectives. We included in the technical perspective those who obtained their degree in a technical course, for example, engineering and/or are working/have worked in a technical job/role during their career, while others were included in the non-technical perspectives. Figure 6 shows that the technical group attributed relatively high average weight to investment and socio-environmental impact issues. Emphasizing on impact, a Monash staff member with a background in environmental engineering considered the potential of the prototype to help address the key barriers and challenges to reach net zero emissions, he stated: “For me, getting people involved in the impact potential is critical. More important than the effort involved to get there” (P10). Another participant placed greater emphasis on investment and pointed to capital expenditure as a critical consideration in terms of how much an option financially constrains capability in other options (opportunity cost).

Figure 6. Weighted issues split by technical and non-technical background.

By contrast, those participants identified as “non-technical” considered the extent to which the prototypes can address diversity and inclusion as having a high priority. From this perspective inclusion emphasizes community engagement approaches that include people who might be outside the information space and precinct community representatives from diverse demographics.

This section has highlighted two main findings from MCM interviews: First, performance diversity which was reflected through the varied set of strengths and weaknesses considered by participants for each of the similarly ranked prototypes. The kinds of engagement approaches represented by all four prototypes are seen as viable. While care must be taken around inclusivity and data issues via possible implementation, these approaches have the capacity to provide a voice to precinct citizens’ concerns and enable further agency in data governance at precinct scale. Second, the appraisal diversity outcomes reveal a plurality of self-selected criteria based on individual participant’s subjective worldview, professional background and institutional affiliation. Engagement effectiveness and diversity and inclusion were also viewed as crucial issues in appraising the prototypes and professional background appears to have had some bearing on the prominence of those issues.

5. Discussion

The discussion that follows examines the significance of our findings in relation to our research goal to develop and test a participatory methodology to identify strategies for empowering community engagement in urban data governance processes. We reflect on how deliberative spaces for participation can foster pluralism to promote inclusive community engagement that is sensitive to diverse concerns in the context of our case study. We also explore how empowering community engagement raises important issues related to democratic engagement, value creation and data literacy, and consider some implementation strategies to support the embedding of participatory approaches within specific socio-institutional contexts. The limitations of this study and future research directions are also considered.

5.1. Deliberative spaces for pluralising participation

Our research is relevant to advancing debates in critical urban studies on smart cities. In the literature review, we discussed how the first generation of smart city development has been criticized for failing to realize inclusive community engagement and collaboration with citizens (Kitchin, Reference Kitchin2015; Trencher, Reference Trencher2019). To address concerns that citizen participation in smart cities had become overly instrumental and technocratic, cities and technology vendors responded with a raft of so-called “citizen-centric” offerings, yet critics suggest these market-based solutions have only worked to reproduce top-down managerialism and one-size-fits all solutions (Cardullo and Kitchin, Reference Cardullo and Kitchin2019). Urban studies point toward more recent cases of democratic forms of citizen engagement in Spanish smart cities that attest to the importance of creating deliberative spaces for participation. These contributions argue for more “open-ended explorations” given the “multiplicity of urban knowledge involved” in order to maintain democratic legitimacy and incorporate the perspectives of otherwise marginalized citizens (Smith and Martín, Reference Smith and Martín2021, p. 327).

The participatory approach we developed and tested in this study can support such open-ended, deliberative discussions with a range of participants. Indeed, our findings have generated rich information about a small group of precinct citizens’ perceptions, practices, expectations, and uncertainties related to data governance in the context of a university and technology precinct undergoing net zero transformation. The multiplicity of ideas and perspectives generated by participants suggests that creating deliberative spaces for pluralistic community engagement is an achievable ambition in the design of inclusive data governance approaches. All of the data governance prototypes were considered feasible and were perceived to have different strengths and challenges. The performance appraisal of the prototypes revealed a considerable degree of uncertainty, which points to the benefits of enabling plural and conditional interpretations to complex problems over single definitive solutions to incomplete knowledge which can be misleading and presume consensus (Stirling, Reference Stirling2010a, Reference Stirlingb).

The appraisal of the participant-generated data governance prototypes using MCM provided further insights on precinct citizens’ perspectives in relation to the focal goal of empowering community engagement. Our results from the MCM interviews revealed the high degree of appraisal diversity in terms of criteria, uncertainties and rankings across a range of individual perspectives. This diversity points toward the importance for those who are involved in data governance activities to provide sufficiently diverse options for community engagement and to be mindful of various conditions influencing their potential successful implementation. We argue that participatory multicriteria approaches to community engagement in data governance open up a plurality of perspectives without forcing participants to make trade-offs or settle on a single best option in the appraisal of complex knowledge and policy decisions. Given we found such a diversity of preferences for community engagement, even within a small and less-than-ideal heterogeneous group of participants, it is likely that a more diverse group of participants would have generated an even greater diversity of views. Future research can advance the application and testing of MCM and similar approaches and explore their usefulness for pluralising design and engagement in urban data governance.

5.2. Empowering community engagement in data governance

Our research is also relevant to scholarly debates on empowerment in transition studies in the context of urban data governance. Empowerment is a common theme in much smart city rhetoric which promotes the idea that digital-led innovation can enhance democracy and economic efficiency, yet questions remain about which actors get to play a role and share any benefits (Jacobs et al., Reference Jacobs, Edwards, Markovic, Cottrill and Salt2020). It has also been noted that involving “data subjects” in data governance can lead to greater accountability of data holders and mitigate the risks of technocratic overreach and the misuse of data (Micheli et al., Reference Micheli, Ponti, Craglia and Berti Suman2020). The aim of this study was to develop and test new ways to empower precinct citizens using participatory methods and explore their views, values and ideas about how they can be engaged in data governance. The findings from our research suggest that precinct citizens can be empowered to identify useful data sets and standards; shape the values and principles of specific data communities; and participate in complex decision-making processes. Our research also reveals that design for social innovation and prototyping can recenter the agency of individual and community participants by democratizing the design of future data governance processes.

The results of our study also shed further light on contemporary debates in data governance related to issues of trust, citizen control and the creation of public value (Mulgan and Straub, Reference Mulgan and Straub2019). The DI prototype for example was imagined as a personal data dashboard where users push selective data to share with other precinct citizens. Participants raised relevant insights on the tension between public and private value creation with the latter viewed by one interviewee (P2) as better suited to individual empowerment without proper data sharing protocols in place to support collective achievement (Section 4.3.1). The democratic values embedded in the PP prototype have much in common with new forms of citizen participation in urban planning that promote social innovation. For instance, recent Nordic case studies reveal that experimental citizen participation methods “do not simply happen” and require design, and should function as a means to test out new forms of engagement that are suited to specific contexts, challenges and citizens (Nyseth et al., Reference Nyseth, Ringholm and Agger2019, p. 14). Future research could explore how to incorporate citizen values and concerns in the design of data governance platforms and institutions building on emerging models of data sharing, data cooperatives, data trusts and data sovereignty (Micheli et al., Reference Micheli, Ponti, Craglia and Berti Suman2020).

Critical education about data and ensuring adequate data literacy is another important aspect of democratic engagement in society as we evolve to the digital age (Pangrazio and Sefton-Green, Reference Pangrazio and Sefton-Green2020). Participants in workshop one (problem identification) identified data literacy as a key consideration in data governance, especially in relation to the use of citizen data. The Peer to Peer Learning (P2P) prototype focussed on empowering precinct citizens by enhancing data literacy through informal knowledge sharing between peers to support carbon reduction goals. These issues are further challenged by calls to reconsider “data literacy,” and to think instead about “literacy in the age of data” defined as “the desire and ability to constructively engage in society through and about data” and to promote it for “empowering citizens and communities as free agents,” emphasizing the need for social inclusion given the structural and political inequalities that remain present in data governance considerations (Bhargava et al., Reference Bhargava, Deahl, Letouzé, Noonan, Sangokoya and Shoup2015, p. 23). New issues to explore include the role of data literacy in empowering community engagement in data governance, especially to support social inclusion.

5.3. From design for social innovation to design for sustainability transitions

Finally, this study has implications for design for social innovation scholarship and practice in terms of the implementation of our participatory approach, along with further testing and refinement of the prototypes. Reflecting on our results, we can now argue that our participatory research opened up a plurality of perspectives about data governance by utilizing design for social innovation methods to prototype potential solutions and evaluate them using MCM. While design for social innovation can empower actors to trial new social learning processes using enabling tools like prototyping, this approach has been criticized for producing short-term outputs. The Young Foundation has proposed slow prototyping as a long-term approach to facilitate a “scaling-up process,” build capacity for new models to succeed and to meet the needs of specific communities in their local contexts (Hillgren et al., Reference Hillgren, Seravalli and Emilson2011, p. 173). Others have pointed out that design for social innovation tends to focus on design processes at the expense of outcomes and would benefit from greater reflection on issues of power and politics in participation (Ceschin and Gaziulusoy, Reference Ceschin and Gaziulusoy2019). The politics of participation remains central to debates over the legitimacy of sustainability transitions, especially in relation to who participates in, and who has power over transition processes (Markard et al., Reference Markard, Raven and Truffer2012).

Our findings suggest that participants can be empowered to co-design solutions to complex problems that respond to diverse perceptions, practices, expectations, and uncertainties. The design of potential data governance solutions is encouraging but in reality, these ideas will not gain traction unless they are taken up by decision-makers within the university and gain some support from other institutional actors, industry partners, small business owners, residents and other community members within the broader technology precinct. In practice, the implementation of participatory approaches to community engagement in urban data governance remains challenging due to a variety of pre-existing institutional arrangements, path dependencies and political dynamics that involve tensions and frictions (Raven et al., Reference Raven, Sengers, Spaeth, Xie, Cheshmehzangi and de Jong2019). Future research could leverage insights from the emerging field of “design for sustainability transitions” which provides guidance on implementation strategies that consider the need for design experiments to influence border structural changes within specific innovation contexts like the NZP. Design for sustainability transitions uses design approaches like participatory design to support the “transformation of socio-technical systems through technological, social, organizational and institutional innovations” (Ceschin and Gaziulusoy, Reference Ceschin and Gaziulusoy2019, p. 127). Design for sustainability transitions also broadens the scope for practitioners to design operational, tactical and strategic activities that are necessary in transition projects to encourage long-term thinking and the experimentation required in socio-technical system transformation (Loorbach, Reference Loorbach2010; Ceschin and Gaziulusoy, Reference Ceschin and Gaziulusoy2019, p. 132).

The emerging scholarship on design for sustainability transitions sheds further light on the strengths and challenges of using participatory design to empower community engagement. It also reveals the need for deeper engagement with transition dynamics, scaling-up processes and the politics of transitions in the future design of urban data governance processes. Embedding is another strategy that has been used to foster implementation through the adoption of the “design, approach or outcomes” of socio-technical experimentation into local structures or communities of practice (von Wirth et al., Reference Von Wirth, Fuenfschilling, Frantzeskaki and Coenen2019, p. 232). Future work could focus on the development of implementation strategies to influence the adoption of our participatory methodology with actors in the precinct responsible for data governance using emerging insights on design for sustainability transitions (Ceschin and Gaziulusoy, Reference Ceschin and Gaziulusoy2019). Specifically, how to develop transition strategies to support longer-term community engagement in data governance, utilizing insights on transformative processes to support the embedding and scaling of niche innovations and the politics of transitions (Schot et al., Reference Schot, Kivimaa and Torrens2019). Finally, we have additional questions about how community engagement in data governance can support net zero transformation at precinct scale in the context of socio-technical systems innovations through urban living lab approaches. Net zero is the guiding purpose for the case study in question, and further research questions could explore how specific processes of community engagement in data governance could accelerate decarbonization goals.

5.4. Limitations

Despite the promising results in the development and testing of a participatory methodology to identify approaches to community engagement, this study has a number of limitations. The research team acknowledge that choices were made in the first workshop on problem identification in the selection of data gathered and the qualitative coding of results. Themes were independently interpreted by members of the research team and then collaboratively synthesized following a process of active categorization informed by the research question. Prototyping also requires researchers to make selective choices in terms of framing the design challenge and interpreting the creative outputs developed by participants. While the study is not intended to be representative of the precinct population, only a small number of precinct citizens participated in a single series of two workshops and interviews over a short time frame. We also acknowledge there was a higher proportion of university staff (professional and academic) and students (undergraduate and postgraduate) that participated in the study compared to other precinct groups.

Beyond these methodological limitations, an important limitation of our approach is that while it enables the development of prototypes, whether or not they come to make a difference will depend on the precinct regime in which they are to be implemented. We recognize the significant challenges and potential barriers to implementation of novel participatory approaches to community engagement in data governance, like the one presented in this article. The politics of incumbency underscores the power imbalances that exist between incumbent actors and niche innovators and between formal actors and grassroots actors (Kemp et al., Reference Kemp, Loorbach and Rotmans2007). And yet, our case study of a precinct undergoing net zero transformation also represents a window of opportunity to trial further experiments in empowering community engagement and embedding participatory governance at precinct scale (Sharp and Raven, Reference Sharp and Raven2021). From a practical perspective, further trials of our participatory approach could test implementation strategies and enroll larger numbers of precinct citizens to participate, no doubt increasing the diversity of perspectives.

6. Conclusion