Inadequate dietary iodine intake during pregnancy, and resulting iodine deficiency, can cause maternal and fetal hypothyroidism and impair neurological development in the fetus( Reference Zimmermann 1 ). In populations at risk of iodine deficiency, the WHO, International Council for Control of Iodine Deficiency Disorders and UNICEF recommend assessing urinary iodine concentration (UIC) in spot urine samples among school-aged children and/or pregnant women( 2 ). Previous assessments of iodine deficiency have often relied on school-aged children because they are not only vulnerable to iodine deficiency but also easily accessible at schools( 2 ). However, recent reports have shown that children’s iodine status often does not reflect iodine status in pregnant women and thus may result in underestimating the risk of iodine deficiency in the most vulnerable populations( Reference Gowachirapant, Winichagoon and Wyss 3 – Reference Ategbo, Sankar and Schultink 5 ). Thyroglobulin (Tg) is also a recommended indicator in school-aged children, reflecting longer-term iodine intake than UIC( 2 , Reference Zimmermann, Moretti and Chaouki 6 ); and Tg can be measured on dried blood spots (DBS)( 2 ). However, the usefulness of Tg as a biomarker of iodine status during pregnancy is unclear( Reference Ma and Skeaff 7 ).

In areas at risk of iodine deficiency, salt iodization is the most cost-effective strategy to prevent iodine deficiency( 2 ). Over 120 countries around the world implement salt iodization programmes and many countries have successfully eliminated iodine deficiency disorders or made substantial progress in their control( 8 ).

The present study was implemented in the Zinder region, which is mainly a rural, agricultural zone in south-eastern Niger. Niger has the highest total fertility rate in the world, 7·6 children per woman, and the tenth highest mortality rate for children under 5 years of age( 9 ). Results from the 2012 Niger Demographic and Health Survey indicated that rates of undernutrition and anaemia are among the highest in the Zinder region( 10 ). No recent surveys of iodine status are available from school-aged children in Niger. However, two small studies recently assessed UIC in pregnant women in Niamey and in breast-feeding infants and their mothers in Dosso( Reference Sadou, Seyfoulaye and Malam Alma 11 , Reference Sadou, Moussa and Alma 12 ) and concluded that iodine status was inadequate among the women. This is in spite of mandatory salt iodization since 1996. The present regulations require an iodine content of 30–60 ppm at the time of importation and 20–60 ppm at retail( Reference Kupka, Ndiaye and Jooste 13 , 14 ). The 2012 Demographic and Health Survey reported that national household coverage of salt containing any iodine was only 58·5 %( 10 ).

The objectives of the present study were to:

-

1. assess iodine status among pregnant women and the household coverage of iodized salt in rural Zinder, Niger;

-

2. compare the iodine status of the pregnant women with the iodine status of school-aged children from the same households; and

-

3. evaluate the validity of Tg concentration in assessing iodine status among pregnant women.

Methods

Study design and participants

The present assessment of iodine status among pregnant women and school-aged children is a cross-sectional study embedded into the Niger Maternal Nutrition (NiMaNu) Project, which was registered with the US National Institutes of Health (www.ClinicalTrials.gov; NCT01832688). The study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the National Consultative Ethical Committee (Niger) and the Institutional Review Board of the University of California, Davis (USA). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Briefly, eighteen rural health centres from two health districts in the Zinder region were selected to participate in the NiMaNu project. In each community, pregnant women were randomly selected and invited to participate in the survey. They were eligible if they provided written informed consent, had resided in the village for at least 6 months and had no plans to move within the coming 2 months. Pregnant women were ineligible if they had severe illness warranting hospital referral or were unable to provide consent due to mental disabilities. Children were eligible if they had written parental consent, lived in the same household as an enrolled pregnant woman, shared regular meals with the pregnant woman and were 5–15 years of age.

Study procedures and outcomes

The iodine assessment was implemented from April 2014 to July 2015. The NiMaNu survey consisted of two contacts with each pregnant woman: (i) a home visit; and (ii) a follow-up visit 1 month later in a centralized location in her village. Among all survey participants, information on socio-economic status, including the Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS)( Reference Coates, Swindale and Bilinsky 15 ), and anthropometric measurements were completed during the home visit. Women’s and children’s weights, heights and mid-upper arm circumferences were measured to 50 g precision (SecaScale model 874; Seca, Hamburg, Germany), to 0·1 cm precision (SecaStadiometer model 217; Seca) and 0·1 cm precision (ShorrTape© Measuring Tape; Weigh and Measure, Olney, MD, USA), respectively. For logistical reasons, school-aged children were asked to provide a spot urine sample during the home visit and pregnant women during the 1-month follow up visit, where a 7·5 ml venous blood sample was also drawn from pregnant women as part of the NiMaNu baseline survey. DBS were collected in pregnant women for assessment of Tg (DBS-Tg) concentration.

Enrolling an adequate number of woman–child pairs was challenging due to a lower number of school-aged children in households than anticipated and a higher number of women giving birth before the follow-up visit. Thus, the enrolment strategy had to be adjusted twice: initially every fourth woman was randomly selected to participate in the iodine assessment. Subsequently, all women living in a household with a school-aged child were invited to the iodine assessment. Lastly, we also enrolled women without a school-aged child to meet the target sample size for study objective 3.

The iodine content of salt samples from randomly selected households participating in the NiMaNu survey were tested using the rapid test for salt iodization (MBI, Madras, India), which can differentiate between iodine concentrations above and below 15 ppm. As recommended for quality control( Reference Rohner, Zimmermann and Jooste 16 ), in a randomly selected sub-sample of 108 salt samples, the iodine content was assessed quantitatively by titration at the University of California, Davis (Davis, CA, USA)( Reference Sullivan, Houston and Gorstein 17 ). Water samples (n 37) were collected from the primary water source of randomly selected households for assessment of iodine concentration.

Urine, water and DBS samples were stored at −20°C until shipment on ice packs to the ETH Zurich, Switzerland for analyses. Urine and water samples were assessed for iodine concentration using a modification of the Sandell–Kolthoff reaction( Reference Jooste and Strydom 18 ). DBS-Tg concentrations were analysed by a newly developed sandwich ELISA assay( Reference Stinca, Andersson and Erhardt 19 ). DBS were analysed for thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) and total thyroxine (TT4) concentrations by an automated time-resolved fluoroimmunoassay (DELFIA neonatal TSH and T4 assays; PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Turku, Finland)( Reference Torresani and Scherz 20 ). The normal range for UIC of school-aged children is 100–199 µg/l and for pregnant women is 150–249 µg/l( 2 , 21 ). There is currently a recommended normal range for Tg assessed in DBS available for school-aged children (4–40 µg/l), but not for pregnant women( 2 ); the former reference range was used for the pregnant women. Trimester-specific normal ranges were used for TSH: 0·2–3·0 mU/l in the second trimester and 0·3–3·0 mU/l in the third trimester( Reference Stagnaro-Green, Abalovich and Alexander 22 ). The manufacturer’s normal reference range for TT4 (65–165 nmol/l) was increased by 1·5-fold to 97·5–247·5 nmol/l to reflect the natural increase of TT4 during pregnancy( Reference Baloch, Carayon and Conte-Devolx 23 ).

Sample size

To detect a prevalence of 50 % of low UIC among pregnant women and school-aged children with a 95 % CI for the estimation of mean prevalence ±5 %, the total sample size needed was 384 (objectives 1 and 2). The sample size estimate for objective 3 was 506, which was based on an effect size of 0·25 sd in Tg concentration between two groups of women (high and low UIC) with a significance of P=0·05 and power=0·80. This magnitude was observed in the multi-country survey of schoolchildren( Reference Zimmermann, Aeberli and Andersson 24 ). An attrition rate of 15 % was included, resulting in a target sample size of 452 for objectives 1 and 2 and 595 for objective 3.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were carried out using the statistical software package SAS for Windows version 9.4. Descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation; median and interquartile range (IQR); number and proportion) were used to assess baseline information of the two population groups and to report concentrations of UIC, DBS-Tg, TSH and TT4. A statistical analysis plan was created prior to analysis( Reference Hess and Ouedraogo 25 ). Spearman’s rank-order correlation test was used to determine the strength of association between the UIC of women and the UIC of school-aged children in the same households. Spearman’s rank-order correlation test was also used to determine the correlation between DBS-Tg concentration and UIC in the same woman. The t test using log-transformed values was used to compare the concentrations of UIC, DBS-Tg, TSH and TT4 of younger women v. older women (defined as above and below the median age), as well as women who were primiparous v. women who were multiparous. Similarly, iodine status was compared between women in the second trimester and those in the third trimester. ANOVA on the log-transformed UIC variable was performed to explore differences between food security category and UIC in women and children. The χ 2 goodness-of-fit test was used to assess the relationship between HFIAS category and iodine content assessed by rapid test.

Results

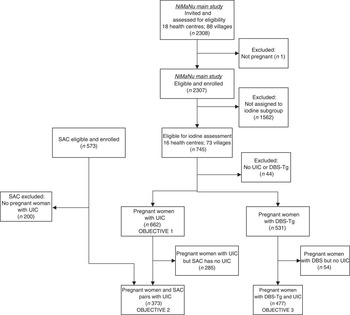

A total of 2307 pregnant women from villages belonging to eighteen health centres were enrolled in the main NiMaNu project. The iodine assessment was implemented in sixteen of these health centres and women from seventy-three villages were eligible. We consented 745 pregnant women and 573 school-aged children to the iodine sub-study (Fig. 1). Among the 662 pregnant women with a urinary spot sample, 373 women–children pairs provided UIC and 477 women provided both UIC and DBS-Tg concentrations. The mean age of pregnant women was 27·7 (sd 6·2) years and almost all women were estimated to be in the second (27·5 %) or third trimester (61·6 %; Table 1). Almost a quarter of all pregnant women (23·7 %) had low mid-upper arm circumference (<23 cm), indicating undernutrition. Children were 7·7 (sd 2·2) years of age. As expected due to the sampling scheme, the age of women with UIC was significantly higher than the age of women in the NiMaNu project who were either not invited to the iodine assessment or did not provide a urine sample (27·7 (sd 6·2) v. 25·1 (sd 6·3) years; P<0·0001). Similarly, women with UIC were less likely to be primiparous then those without UIC information (9·1 v. 15·6 %; P<0·0001).

Fig. 1 Flow diagram of clusters and participants through the iodine status assessment of the Niger Maternal Nutrition (NiMaNu) Project (SAC, school-aged child(ren); UIC, urinary iodine concentration)

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of pregnant women and school-aged children in Zinder, rural Niger

Min–max, minimum–maximum; HFIAS, Household Food Insecurity Access Scale.

* Iodine content of salt samples was assessed by rapid test (MBI, Madras, India) in 554 households.

† Iodine content was assessed by iodometric titration in a randomly selected subset of 108 households.

Twenty-two households (3·8 %) had no salt available at the time of the household visit. Forty-one per cent of salt samples tested in 554 households using the rapid test kit contained no detectable iodine (Table 1). The low coverage of salt iodization was confirmed by iodometric titration; the majority (98·1 %) had an iodine content below the minimum required amount of 20 ppm mandated at the retail level in Niger. The median (minimum–maximum) iodine content of salt was 5·5 (0·6–41·3) ppm. Among the thirty-seven water samples collected from the primary water source of randomly selected households, thirty-two (86·5 %) had an iodine content below the detectable limit of 6 µg/l. Of the remaining five water samples, the iodine concentration ranged from 6·8 to 19·7 µg/l.

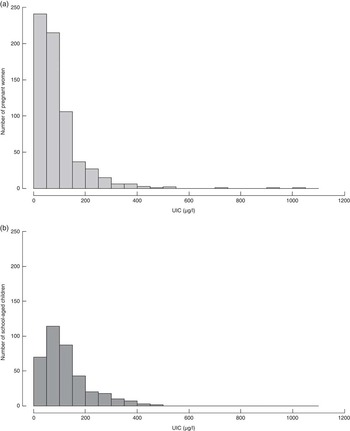

Among women who provided a urine sample (n 662) the median UIC was 69·0 (IQR 38·1–114·3) µg/l, which is below the recommended cut-off of 150 µg/l (Table 2). When considering only pregnant women who were also part of the woman–child pairs, the median UIC was 69·5 (IQR 38·0–112·6) µg/l (n 373; Fig. 2). There was no significant difference between the ranked-sum of the UIC of these two groups of women (P=0·817). The median UIC of school-aged children (n 373) was 100·9 (IQR 61·2–163·2)µg/l and <20 % had UIC below 50 µg/l, thus implying adequate iodine status. Although UIC of pregnant women and school-aged children in the same households were correlated (r s=0·24; P<0·0001), this association was weak.

Fig. 2 Distribution of urinary iodine concentration (UIC) in (a) pregnant women and (b) school-aged children living in the same households in Zinder, rural Niger

Table 2 Urinary iodine concentrations in pregnant women and school-aged children and thyroglobulin concentration in pregnant women in Zinder, rural Niger

Min–max, minimum–maximum; UIC, urinary iodine concentration; DBS-Tg, dried blood spot thyroglobulin; TT4, total thyroxine; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone.

* Subclinical hypothyroidism defined as increased TSH (>3·0 mU/l) and normal TT4 (97·5–247·5 nmol/l).

† Overt hypothyroidism defined as increased TSH and low TT4 (<97·5 nmol/l).

‡ Hypothyroxaemia defined as low TT4 (<97·5 nmol/l).

The median of DBS-Tg concentration of pregnant women was 34·6 (IQR 23·9–49·7) µg/l. Over one-third of women (38·4 %) had DBS-Tg concentration >40 µg/l, which is above the normal range recommended for school-aged children. The ranked-sum of the UIC among women with and without DBS-Tg concentrations were not different (P=0·772). The UIC and DBS-Tg concentration of pregnant women were not correlated (r s=−0·0804; P=0·079). Subclinical hypothyroidism was found in four (0·8 %) women only.

There was no clear pattern between HFIAS category and iodine content of salt assessed by rapid test kit. Household food insecurity, as assessed by HFIAS, was not associated with UIC of pregnant women (P=0·597) or of school-aged children (P=0·108). The median UIC of pregnant women younger than the median age and pregnant women older than the median age were 71·5 (IQR 38·8–120·0) and 67·2 (IQR 37·5–109·0)µg/l, respectively; and those of primiparous and multiparous women were 72·9 (IQR 41·7–113·8) and 68·4 (IQR 37·5–114·6)µg/l, respectively. Mean concentrations of UIC, DBS-Tg, TT4 and TSH did not differ by age group or between primiparous and multiparous women, nor was there a significant difference in the prevalence of low and high concentrations of these indicators (data not shown). There were also no significant differences in iodine status defined by any of the iodine status indicators between women in the second or third trimester (data not shown).

Discussion

The low coverage of iodized salt and the low median UIC in pregnant women in rural villages of Zinder, Niger indicate a need for immediate action. WHO and UNICEF recommend that countries, or areas within countries, in which less than 20 % of the households have access to adequately iodized salt should assess the current situation of the salt iodization programme to identify national or sub-national problems and to update strategies and action plans( 26 ). Considering the critical role of iodine during pregnancy and early childhood, WHO and UNICEF recommend that pregnant and lactating women should be supplemented with iodine and children aged 7–24 months should be given either a supplement or complementary food fortified with iodine until the salt iodization programme is scaled up( 26 ).

Surveys to assess the iodine status of a population are often implemented in school-aged children due to the easy access( 2 ). The present survey is the first in an African country with low salt iodization household coverage to confirm concerns that the surveys in school-aged children tend to underestimate the risk of iodine deficiency among the most vulnerable population groups. In particular, the present study in rural Niger confirms an earlier finding in central Thailand, where the UIC in pregnant women suggested iodine deficiency while the UIC of their school-aged children indicated adequate iodine status. Namely, the median (minimum–maximum) UIC of Thai pregnant women was 108 (11–558) µg/l compared with 200 (25–835) µg/l among school-aged children( Reference Gowachirapant, Winichagoon and Wyss 3 ). The difference between the two groups was less in a study in Rajasthan, India, where the median UIC of pregnant women was 127 (IQR 55–230) µg/l compared with 139 (IQR 70–254) µg/l in school-aged children of the same households( Reference Ategbo, Sankar and Schultink 5 ). Because of the different cut-offs to define iodine deficiency in school-aged children and pregnant women, these surveys in Thailand and India suggested adequate iodine status in school-aged children and iodine deficiency in pregnant women. In a cross-sectional study of households in Bangalore, India, median (range) UIC in women was 172 (5–1024)µg/l indicating iodine sufficiency while median (range) UIC in their school-aged children was 220 (10–782)µg/l, indicating more-than-adequate iodine intake( Reference Jaiswal, Melse-Boonstra and Sharma 27 ). Taking the above summarized findings together, some national salt iodization programmes seem to be able to meet the iodine requirements of school-aged children, but may provide insufficient iodine to meet the increased iodine requirements of pregnant women.

The findings in pregnant women in rural Zinder confirm two recent small studies which assessed UIC in pregnant women in Niamey and in breast-feeding infants and their mothers in Dosso and concluded that iodine status was inadequate( Reference Sadou, Seyfoulaye and Malam Alma 11 , Reference Sadou, Moussa and Alma 12 ). Our findings of low coverage with adequate iodized salt confirm those from the 2012 Niger Demographic and Health Survey, which reported that the national average household coverage of salt containing any iodine was only 58·5 %, and 30·1 % in the region of Zinder( 10 ). In the present study, iodometric titration found that only 2 % of salt samples contained 20 ppm of iodine, even though the mandated iodine content of salt at the retail level in Niger is 20–60 ppm( 14 ). We also found undetectable iodine concentrations in the majority of water samples, suggesting this is not a source of iodine intake in this region. Assuming the children in this area excrete ≈1 litre of urine daily, their median UIC would correspond to an iodine intake of about 100–110 µg/d. Considering the low amounts of iodine in salt and water, it is likely there are other source(s) of dietary iodine in the area. In West Africa, bouillon cubes used for seasoning often contain iodized salt and can be a significant source of iodine for children, as shown in a recent study in northern Ghana( Reference Abizari, Dold and Kupka 28 ). Bouillon cubes are consumed in rural Niger, and some of the brands sold on local markets contain 1–2·8 mg of iodine per 100 g. Nevertheless, it is unclear why the UIC of school-aged children implied marginally adequate iodine status considering the very low iodine content of salt. Strengthening of the salt iodization programme in Niger should be a priority.

Despite their low iodine intakes, the majority of pregnant women in the present study maintained euthyroidism. By upregulating iodine uptake and thyroid hormone secretion, thyroid metabolism can adjust not only to the requirements of the pregnancy but also to low dietary iodine intake( Reference Stagnaro-Green, Abalovich and Alexander 22 , Reference Glinoer 29 ). Thus, TSH and thyroid hormones are insensitive biomarkers of iodine deficiency( 2 ). In contrast, Tg may be a sensitive indicator of iodine status in children( 2 , Reference Zimmermann, Moretti and Chaouki 6 ) and non-pregnant women( Reference Ma and Skeaff 7 ). However, the usefulness of DBS-Tg during pregnancy is uncertain( Reference Ma and Skeaff 7 ). Tg may increase moderately in iodine-deficient women during pregnancy( Reference Eltom, Elnagar and Elbagir 30 ), possibly due to increased stimulation of thyroid hormone secretion to meet increased maternal and fetal requirements. Elevated Tg concentrations are expected during pregnancy due to high oestrogen levels( Reference Pearce 31 ). In the present study, DBS-Tg concentration was above the normal range recommended for school-aged children in over one-third of the pregnant women. However, in our study population of pregnant women, DBS-Tg and UIC were not well correlated, as previously reported among pregnant women in France and New Zealand( Reference Brucker-Davis, Ferrari and Gal 32 , Reference Brough, Jin and Shukri 33 ). Nevertheless, compared with TSH and TT4, DBS-Tg may be a more sensitive indicator of iodine deficiency in pregnant women. Further research is required to assess the usefulness of DBS-Tg as an indicator of iodine status during pregnancy.

Strengths of the current study include the sample size, the use of multiple iodine status indicators among pregnant women and that the iodine status assessment was coupled with assessment of the household coverage of iodized salt. Several limitations also have to be considered. In particular, this was a convenience sample derived from the NiMaNu project and may thus not be representative regionally or nationally. Because one of the study objectives was to compare UIC between pregnant women and school-aged children in the same households, women who participated in the iodine assessment tended to be older and multiparous compared with women in the NiMaNu project. However, there was no significant difference in concentrations of UIC, DBS-Tg, TSH and TT4 between primiparous and multiparous women or between younger and older women; this suggests that the women in the present iodine status assessment were comparable to the randomly selected cohort of pregnant women in the study area of rural Zinder.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the present study identified iodine deficiency in pregnant women in rural Niger and a very low household coverage of adequately iodized salt. In observational studies, even mild iodine deficiency during pregnancy has been associated with impaired neurodevelopmental outcomes in the offspring( Reference Bath, Steer and Golding 34 , Reference Hynes, Otahal and Hay 35 ). Thus, strengthening the national salt iodization programme in Niger should be a priority. In the meantime, the provision of supplemental iodine to pregnant women should be considered( 26 ). In contrast to pregnant women, the iodine status of school-aged children living in the same households and sharing regular meals with the pregnant women was just adequate. Monitoring iodine status using the median UIC in school-aged children tends to underestimate the risk of iodine deficiency in pregnant women. To assess the risk of iodine deficiency among pregnant women, UIC needs to be measured in pregnant women.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors thank the entire study staff, and sincerely appreciate the support of the participating women, children and their families, the local communities and the staff of the Health District of Mirriah and Zinder. Financial support: The iodine add-on study was funded by Global Affairs Canada (GAC) (grant number 10-1422-UCALIF); the Micronutrient Initiative; and UNICEF. None of the funders had a role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: S.Y.H. designed the study, C.T.O. and I.F.B. implemented the research, S.Y.H. and K.R.W. supervised data collection, S.S. and M.B.Z. were responsible for laboratory analyses, R.T.Y. completed the statistical analyses and S.Y.H. drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the National Consultative Ethical Committee (Niger) and the Institutional Review Board of the University of California, Davis (USA). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.