A healthy eating pattern in early childhood is crucial for the adequate growth and development of children( Reference Bellisle 1 , Reference Uauy, Kain and Mericq 2 ). Furthermore, nutrition in childhood plays an important role in the development of chronic diseases later in life, such as metabolic syndrome, diabetes and CVD( Reference Dehghan, Akhtar-Danesh and Merchant 3 , Reference Bammann, Peplies and Pigeot 4 ). Dietary variety can be seen as an indicator of a healthy eating pattern. Consuming a variety of foods helps to ensure adequate intakes of nutrients and other beneficial substances( Reference Drewnowski, Henderson and Driscoll 5 – Reference Kant, Schatzkin and Harris 9 ). Research shows that a greater dietary variety is associated with a higher consumption of fruit and vegetables( Reference Drewnowski, Henderson and Driscoll 5 ), a lower risk of chronic diseases( Reference Kant, Schatzkin and Harris 9 ) and a lower mortality risk( Reference Tucker 7 ). Therefore, children must be encouraged to adopt a healthy and varied eating pattern.

Biologically, children tend to reject unfamiliar foods, a phenomenon called food neophobia( Reference Birch 10 – Reference Birch 12 ). Food neophobia can, however, be overruled, as taste preferences are shaped mainly by learning( Reference Birch and Fisher 13 , Reference Westenhoefer 14 ). In the literature, three processes are indicated to modify innate taste preference: (i) repeated experience of tasting food products; (ii) creation of associations between the physiological consequences of food products and their taste; and (iii) social influences( Reference Birch 11 , Reference Westenhoefer 14 , Reference Contento 15 ). Taking these processes together, repeatedly offering food products to children in a positive context increases taste acceptance( Reference Westenhoefer 14 , Reference Dovey, Staples and Gibson 16 ). Especially people in their close environment, such as parents, teachers and friends, play an important role in the development of children’s taste acceptance( Reference Westenhoefer 14 , Reference Rozin 17 ). In school settings, teachers have the opportunity to expose children to food and teach them about how to make healthy food choices. Also, they can create a social norm in which tasting unfamiliar foods is normal.

Although taste acceptance has been shown to be important in the promotion of healthy eating patterns among children, only a few school-based interventions have been developed that focus on taste acceptance. The French programme ‘Classes du Goût’, known as the SAPERE method, consists of twelve lessons for 8–10-year-old children and aims at encouraging children to taste unfamiliar foods. An evaluation of this programme showed a significant reduction of food neophobia and an increase in willingness to taste unfamiliar foods( Reference Reverdy, Chesnel and Schlich 18 ). The ‘SNAP-Ed’ intervention from the USA consists of four lessons for 8–9-year-old children, including food tasting and assignments. An evaluation of these lessons found a significant increase in preference, knowledge, attitude and self-efficacy towards eating vegetables( Reference Wall, Least and Gromis 19 ). In The Netherlands, the nutrition education programme ‘Taste Lessons’ (Smaaklessen) was developed for elementary schools to improve children’s taste acceptance. It includes lessons on taste, healthy eating behaviour and food quality. Although 33 % of the elementary schools in the Netherlands have implemented Taste Lessons, the programme’s effect has not yet been evaluated. The present study investigates the effect of children’s exposure to Taste Lessons during a single school year on behavioural determinants towards the target behaviours of tasting unfamiliar foods and eating healthy and a variety of foods.

Methods

Intervention design

Taste Lessons is a national school-based nutrition education programme, developed by the Netherlands Nutrition Centre and Wageningen University for grades 1–8 of elementary schools( 20 ). When a school registers for Taste Lessons, teachers are invited to attend an introductory workshop. In this workshop, the aim of the programme and the way it can be implemented at school are discussed. At the end of the workshop, the school receives a toolkit with teacher manuals and materials. The programme consists of ten to twelve lessons discussing various topics in relation to three themes: (i) ‘taste’; (ii) ‘nutrition and health’; and (iii) ‘food quality’. Each lesson consists of three to nine activities including experiments, cooking and tasting. Some lessons include home assignments which children are to complete with their parents. For each lesson, also tips for extra activities are provided, such as visiting a farmer. Teachers can implement Taste Lessons in a flexible way. They can, for instance, spread the lessons over a couple of weeks or cluster them in a project week. On average, the teachers implemented a third of the Taste Lessons programme.

Study design and procedure

A quasi-experimental design was used to assess the effect of Taste Lessons. The study was carried out among 1183 children of forty-nine classes in grades 5–8 in twenty-one elementary schools. At the start of the 2011–2012 school year (September to December 2011), research assistants visited both intervention and control schools to collect baseline information. The children were requested to complete a questionnaire in the classroom with the supervision of a research assistant.

During the school year, teachers in the intervention group were asked to notify the research team when they planned to teach their last lesson of Taste Lessons. Four weeks and six months after the teachers taught this lesson (February–June and September–December 2012), two consecutive follow-up measurements were conducted. During these measurements, schools were visited by the research team to get the children to complete the same questionnaire as at baseline. Because of busy schedules and separated classes, five schools (three intervention and two control schools) received the questionnaires for the second follow-up measurement by post and let the children fill out the questionnaire without guidance of a research assistant.

Schools in the control group were matched with schools in the intervention group based on grade, month of baseline measurement and province. Subsequently, the first and second follow-up measurement in the control group took place in the same period as the matched schools in the intervention group. The effect of Taste Lessons was measured by comparing changes in behavioural determinants (follow-up minus baseline) between the intervention group and the control group.

Study population

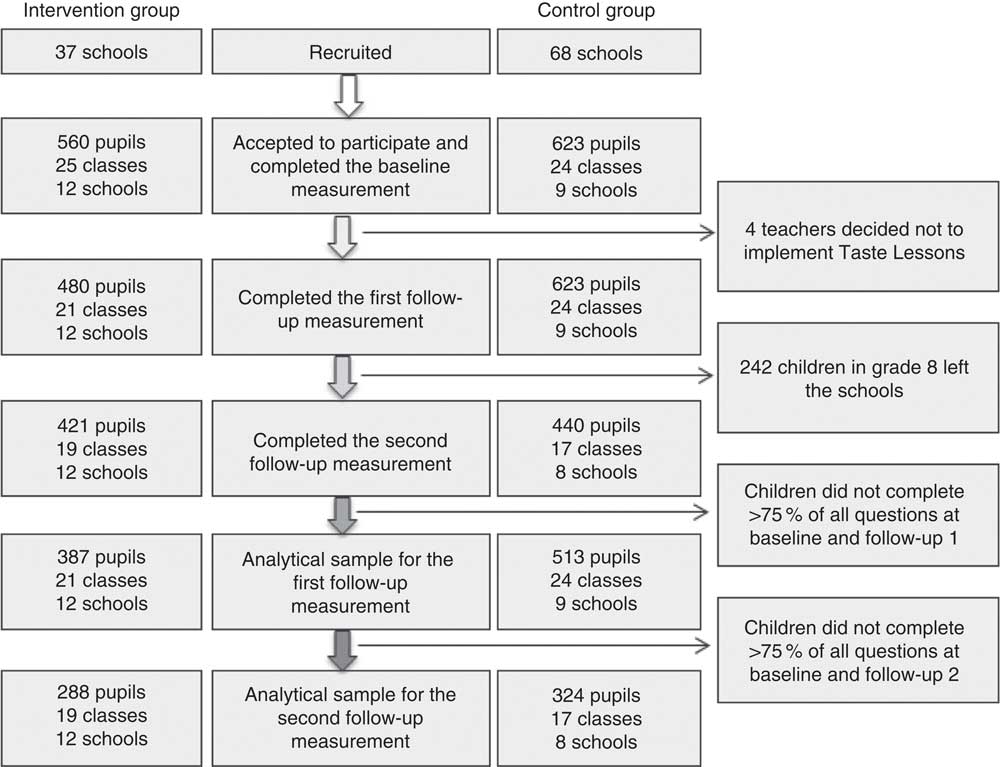

Elementary schools in the centre of the Netherlands that had registered for Taste Lessons and had followed an introductory workshop were invited to join the intervention group. Schools were included when they planned to teach Taste Lessons in grades 5–8, were not previously enrolled in Taste Lessons and were not planning to participate in any other nutrition-related programme. Twelve out of thirty-seven schools met the inclusion criteria and were willing to participate (32 %; Fig. 1). From these schools, twenty-five classes participated. To recruit schools for the control group, a list was consulted with all elementary schools in the Netherlands. From this list, schools in the centre of the Netherlands and schools not registered for Taste Lessons were randomly approached to participate in the study. The schools were eligible to participate when they were not enrolled in any other nutrition-related programme outside their regular school curriculum. Nine (twenty-four classes) out of sixty-eight schools were willing to participate (13 %).

Fig. 1 Flowchart of participants during the measurements and analyses

All recruited schools and classes participated in the baseline measurement. After the baseline measurement, four classes of different schools in decided not to provide Taste Lessons that school year. This reduced the intervention group for the first follow-up measurement to twenty-one classes in twelve schools (84 % of the baseline group). All twenty-four classes in the control group participated in the first follow-up measurement.

Since the second follow-up measurement took place in the next school year, most classes had new teachers who had to be recruited for participation in the study. One teacher in the control group was not willing to participate. Furthermore, children in grade 8 started the next school year in the first grade of secondary school and were excluded for the second follow-up measurement due to practical reasons. This resulted in a study population of nineteen classes in twelve schools upon the second follow-up measurement in the intervention group (76 % of the baseline group). The study population of the control group consisted of seventeen classes in eight schools (71 % of the baseline group).

Measures

Behavioural determinants

Changes in behavioural determinants towards the two target behaviours (i.e. tasting unfamiliar foods and eating healthy and a variety of foods) were selected as outcome measures. Based on the ‘integrative model of behavioural prediction’ by Fishbein et al.( Reference Fishbein, Triandis and Kanfer 21 ), four determinants were selected: (i) skills; (ii) attitude; (iii) subjective norm; and (iv) intention. Since Taste Lessons aims to change children’s eating behaviour in a positive and playful way, attitude was divided in rational (attitude) and emotional (emotion) thoughts and feelings. Furthermore, knowledge and awareness were selected as relevant determinants. Children’s knowledge was assessed by questions based on what they were taught during Taste Lessons. Awareness was measured by questions on how often children perform behaviours related to the target behaviours (scale from 1=‘never’ to 5=‘always’). From the Taste Lessons materials, four skills were selected which are related to the target behaviours. In the questionnaires, the children were asked if they were able to perform the particular skill (‘no’, ‘a little’, ‘yes’). Questions and scales for attitude and emotion (‘How much do you think the target behaviours are clever/interesting and nice/cool/tasty?’), subjective norm (’How much do you think your classmates/parents/teacher wants you to perform the target behaviours?’) and intention (‘How much are you planning to perform the target behaviours?’) were used as described by Ajzen and Fishbein( Reference Ajzen and Fishbein 22 ) and were formulated in a way that is simple and understandable for children (scale from 1=‘no, not at all’ to 5=‘yes, totally’). In addition, four determinants were selected to assess the effect on taste acceptance for sixteen selected foods: (i) number of foods known (‘yes’, ‘no’); (ii) number of foods tasted (‘yes’, ‘no’); (iii) expected positive taste of foods (‘yes’, ‘a little’, ‘no’); and (iv) willingness to taste unfamiliar foods (‘yes’, ‘maybe’, ‘no’). A questionnaire was developed to be filled out by the children themselves. Since the lessons for grades 5–6 differ from the lessons for grades 7–8, questionnaires were developed for both age categories with overlapping and programme-specific questions (Table 1).

Table 1 Content of the questionnaires

† Number of questions in the questionnaire for grades 5–6, grades 7–8 and both questionnaires.

The questionnaires were pre-tested for clarity and length in grades 5–8 of an elementary school and appeared appropriate after small adaptations. With data of the baseline measurement, the sets of questions per determinant were analysed on their internal consistency using Cronbach’s α. All sets of questions scored Cronbach’s α>0·6. We concluded, therefore, that the concepts were assessed adequately. In the data analyses, we used mean score of the answers on these questions. Since single unrelated questions were asked to test different aspects of knowledge, Cronbach’s α was not appropriate. Therefore, a score of correct answers was used in further analyses. Item facility and item discrimination were used as measures of quality. This resulted in the exclusion of questions which either were answered correctly by more than 80 % of the children or poorly correlated to the total score on knowledge (Pearson’s correlation<0·2)( Reference Parmenter and Wardle 23 ).

Sociodemographic factors

Children’s questionnaires included questions on age (in years), gender and ethnicity of the child and parents (country of birth). Children were classified as non-native when they or one of their parents were born outside the Netherlands. Information on the characteristics of the schools was obtained from the online database of Dutch elementary schools( 24 ). The database included location (city, small city or town), religious principle (public or religious) and size of the school (small, <150 pupils; medium, 150–400 pupils; or large, >400 pupils). Socio-economic status score was looked up in another online database( 25 ). This score was based on the degree of education, income and work status of households within zip code districts, ranging from <0 as relatively high social status to >0 as relatively low social status in the district. These sociodemographic factors were considered as potential confounders in further analyses.

Statistical analyses

The statistical software package IBM SPSS Statistics version 19·0 was used for descriptive analyses. First, the intervention group and control group were compared on their sociodemographic characteristics by use of one-way ANOVA. Second, mean scores on the determinants were calculated for children who filled out at least 75 % of the questions in all determinants. Third, change scores were calculated. These consisted of difference in mean score between the baseline measurement and follow-up measurements( Reference Van Breukelen 26 ). In the main analyses, data of grades 5–8 were pooled, including overlapping questions. Stratified analyses were conducted for grades 5–6 and grades 7–8 separately, including the group-specific questions, and specified analyses were conducted for each of the two target behaviours.

Multilevel analyses were performed by use of the program HLM version 7 to evaluate the effect of Taste Lessons on change in behavioural determinants, including three levels: (i) pupil; (ii) class; and (iii) school. First, simple linear regression was used, with the change score of each behavioural determinant as the dependent variable and intervention as the explanatory variable. Second, potential confounders and effect modifiers were identified by adding all sociodemographic factors to the model one by one. From these analyses, children’s age and gender appeared to be significant confounders for most behavioural determinants, whereas no effect modifiers were found. Third, multivariate linear regression analyses were performed, adjusting for children’s age and gender.

With the results of the adjusted analyses, relative effect sizes were calculated for each determinant. These were expressed as Cohen’s d ( Reference Cohen 27 ): the β of the intervention (adjusted difference in change score between the intervention and control group) divided by the total standard deviation over all levels of the adjusted model. A Cohen’s d of 0·2 is interpreted as a small, 0·5 as a medium and 0·8 as a large effect size( Reference Cohen 27 ). Results were interpreted as significant when P<0·05 (two-sided).

Results

Characteristics of the study population

The intervention group included relatively younger children, more boys and more non-native children compared with the control group (Table 2). Furthermore, the intervention group included more schools in cities, more schools with a religious principle, more small schools and more schools in districts of lower socio-economic status than did the control group.

Table 2 Sociodemographic characteristics of the children and schools in the intervention and control group; effect evaluation of the Dutch school-based education programme ‘Taste Lessons’ in forty-nine classes (1183 children, 9–12 years old) in grades 5–8 of twenty-one elementary schools, 2011–2012 school year

SES, socio-economic status.

† A child is labelled as non-native when s/he or at least one parent is born outside the Netherlands. For twenty-eight children in the intervention group and four children in the control group information on ethnicity is missing.

‡ Status score based on the zip code of the school. Mean status score for the Netherlands is 0; values >0 indicate a neighbourhood with more social deprivation.

Effects on change in taste acceptance

Both the intervention and the control group showed a positive change on the determinants related to taste acceptance at both the first and second follow-up measurement (Table 3). The intervention group showed a significantly higher positive change in foods known and foods tasted than the control group. These effects, however, did not remain significant at the second follow-up measurement.

Table 3 Mean scores, change scores and effect sizes for each determinant for grades 5–8 togetherFootnote †; effect evaluation of the Dutch school-based education programme ‘Taste Lessons’ in forty-nine classes (1183 children, 9–12 years old) in grades 5–8 of twenty-one elementary schools, 2011–2012 school year

*P<0·05, **P<0·01, ***P<0·001.

† Mean scores and change scores are unadjusted, but effect sizes are adjusted for children’s age and gender. n 900 at the first follow-up measurement (grades 5–8) and n 592 at the second follow-up measurement (grades 5–7).

Effects on behavioural determinants

Both groups showed a positive change in most behavioural determinants between baseline and both follow-up measurements (Table 3). At the first follow-up measurement, the intervention group showed a significantly higher positive change in knowledge than the control group. This effect remained significant at the second follow-up measurement. Furthermore, at the first follow-up measurement the intervention group showed a significantly higher change in subjective norm of the teacher and intention, and a borderline significantly higher change in awareness than the control group. At the second follow-up measurement, the intervention group showed a borderline significantly higher negative change in emotion compared with the control group.

Stratified analyses for grades 5–6 and grades 7–8

Overall, results of stratified analyses for grades 5–6 and 7–8 were similar to those of the main analyses (Table 4). In grades 5–6, however, no (borderline) significant effect of Taste Lessons was found on number of foods known and intention, but a significantly higher positive change in subjective norm of the parents was found at the first follow-up measurement. Regarding grades 7–8, no (borderline) effects of Taste Lessons were found on number of foods known and subjective norm of the teacher. On the other hand, a borderline significantly higher positive change in attitude was found at the first follow-up measurement.

Table 4 Effect sizes for each determinant, stratified into grades 5–6 and grades 7–8Footnote †; effect evaluation of the Dutch school-based education programme ‘Taste Lessons’ in forty-nine classes (1183 children, 9–12 years old) in grades 5–8 of twenty-one elementary schools, 2011–2012 school year

*P<0·05, **P<0·01, ***P<0·001.

† Effect sizes are adjusted for children’s age and gender. For grades 5–6: n 407 at the first follow-up measurement and n 408 at the second follow-up measurement. For grades 7−8: n 474 at the first effect measurement and n 195 at the second effect measurement.

Specified analyses for the two target behaviours

Overall, results of specified analyses for the target behaviours showed significant effects for both follow-up measurements for determinants similar to those in the main analyses (Table 5). However, some differences appeared between the target behaviours. Subjective norm of the teacher was significant only for tasting unfamiliar foods, whereas intention was significant only for eating healthy and a variety of foods. The negative effect on emotion at the second follow-up measurement in the main analyses was shown to be strongest for eating healthy and a variety of foods.

Table 5 Effect sizes for each determinant per target behaviourFootnote †; effect evaluation of the Dutch school-based education programme ‘Taste Lessons’ in forty-nine classes (1183 children, 9–12 years old) in grades 5–8 of twenty-one elementary schools, 2011–2012 school year

*P<0·05, **P<0·01, ***P<0·001.

† Effect sizes are adjusted for children’s age and gender. n 710 at the first follow-up measurement and n 484 at the second follow-up measurement.

Discussion

The results of the present study show that Taste Lessons in grades 5–8 of elementary school increased children’s knowledge towards tasting unfamiliar foods and eating healthy and a variety of foods. This higher increase in knowledge remained significant six months after the intervention. The number of foods known also showed a significantly higher increase after receiving Taste Lessons.

Furthermore, four weeks after the implementation of, on average, a third of the Taste Lessons programme, a positive effect on the number of foods tasted by children was observed. Other short-term effects were found on children’s subjective norm of their teacher and parents to taste unfamiliar foods (in grades 5–6) and their intention to eat healthy and a variety of foods (in grades 7–8). Finally, Taste Lessons appeared to be inversely associated with children’s enjoyment of eating healthy and a variety of foods in the long term (in grades 7–8).

Reflection on the methods used

In this quasi-experimental study, different methods were used to recruit schools for the intervention and control group. In the intervention group, schools were included that registered for Taste Lessons and participated in the introductory workshop. The control group consisted of a selection of elementary schools located in a similar area as the intervention schools. These schools were approached for participation by the research team. When comparing the characteristics of both groups with those of all Dutch elementary schools, schools in the intervention group appeared representative, whereas the control schools differed in sociodemographic characteristics. These differences may have influenced the change in behavioural determinants. However, only children’s age and gender were found to be significant predictors of change and after controlling for these confounders, the effects of Taste Lessons remained significant. Furthermore, as both groups had mean baseline values at the middle of the scale, a ceiling effect is unlikely to have influenced the results.

For the present study, questionnaires were developed to be filled out by the children themselves. These self-reports may have caused socially desirable answers and measurement errors. For example, children’s cognitive capabilities may have been too limited to sufficiently understand the questions and to provide appropriate answers. With the development of the questionnaire, however, attention was paid to children’s cognitive limitations to reduce measurement errors. Questions and answer scales were developed and piloted. Furthermore, children completed the questionnaire under the supervision of a research assistant, who also instructed the children on how to fill out the questionnaire properly and who was available for questions. As a result, the reliability of questionnaires appeared to be sufficient with Cronbach’s α > 0·6.

Children needed on average 30 min to complete the questionnaire. Although this length appeared to be acceptable at the pre-test of the questionnaire, some children were not able to finish the questionnaire in time, especially children with reading problems. Consequently, the number of unanswered questions on the last pages was higher compared with the number of unanswered questions on the first pages. Since no difference was found in the number of unanswered questions between the intervention and control group, this issue is unlikely to have influenced our results. On the other hand, it has resulted in reduced power of the study, as children’s data were included in the analyses only when at least 75 % of all determinants in the questionnaire had been filled out.

Children in grade 8 were not able to participate in the second follow-up measurement. Since this measurement took place in the next school year, these children had left primary school. The loss of children in grade 8 for the second follow-up measurement might have caused insufficient power to detect long-term effects.

Teachers in the intervention group were free to either implement Taste Lessons in a project week or to spread the lessons over a wider period of time. Consequently, the period between baseline and follow-up measurements differed between the intervention schools. However, teachers were asked to notify the researchers when they planned to teach their last Taste Lesson. Follow-up measurements were taken twice in each intervention school. The first measurement was approximately four weeks after the last Taste Lesson, and the second approximately six months after the last Taste Lesson. Besides, the measurement periods for the intervention and control schools were equal due to matching of schools. These efforts may have reduced potential time effects.

Reflection on the results

Tasting different foods is an essential step in food acceptance( Reference Dovey, Staples and Gibson 16 , Reference Reverdy, Chesnel and Schlich 18 ) and, with that, reaching a healthy and varied eating pattern( Reference Contento 15 , Reference Dovey, Staples and Gibson 16 ). Therefore, an important aim of Taste Lessons is encouraging children to taste unfamiliar foods. The study showed that children in the intervention group tasted more different foods than children in the control group, which suggests that Taste Lessons contributes to children’s taste acceptance. The intervention group, however, did not show a significantly higher increase in willingness to taste unfamiliar foods than the control group. An evaluation of a French study on twelve taste lessons (‘Classes du Goût’, SAPERE method) showed that children’s preferences of the foods they were exposed to in the programme was significantly higher in the intervention group than in the control group. This was the case both directly after the lessons had taken place and ten months after the intervention( Reference Reverdy, Schlich and Köster 28 ). Another evaluation of the same programme showed significant short-term effects on reduction of food neophobia. This outcome is related to willingness to taste unfamiliar foods( Reference Reverdy, Chesnel and Schlich 18 ). The stronger results of these studies might be explained by the higher number of lessons implemented in those studies.

The present study showed a significant increase in children’s knowledge in the longer term. This effect was consistently found in all grades, for both target behaviours and also for the number of known foods. Besides, the study found a borderline significant short-term effect on children’s awareness of eating healthy and a variety of foods, which is closely related to knowledge. Most other evaluation studies on school-based nutrition programmes found an effect on knowledge in the short and the longer term as well, such as ‘High 5’( Reference Reynolds, Franklin and Binkley 29 ), ‘CATCH’( Reference Edmundson, Parcel and Feldman 30 , Reference Auld, Romaniello and Heimendinger 31 ), ‘Be Smart’( Reference Warren, Henry and Lightowler 32 ) and ‘Pathways’( Reference Caballero, Clay and Davis 33 ). No comparisons could be made regarding awareness, since to our knowledge no other evaluation studies have included awareness as an outcome measure.

Although Taste Lessons included many practical assignments, we did not find an effect on skills. Possibly, the type of skills assessed in our questionnaire requires higher exposure to the programme than achieved in the present study. Other evaluation studies of school-based nutrition programmes such as High 5 and CATCH found an effect on children’s self-efficacy, which is closely related to skills( Reference Wall, Least and Gromis 19 , Reference Reynolds, Franklin and Binkley 29 , Reference Auld, Romaniello and Heimendinger 31 , Reference Belansky, Romaniello and Morin 34 , Reference Keihner, Meigs and Sugerman 35 ). The intensity of implemented lessons and activities of most of these programmes was higher than that of Taste Lessons. High 5, for example, consists of twelve lessons focusing solely on fruit and vegetables. In CATCH, a more integral approach was used.

With regard to attitude, we found a borderline significant short-term effect in grades 7–8. Other evaluation studies found a positive effect on attitude in the short or longer term( Reference Wall, Least and Gromis 19 , Reference Auld, Romaniello and Heimendinger 31 , Reference Nicklas, Johnson and Myers 36 , Reference Joshi, Azuma and Feenstra 37 ). In a review of Contento et al.( Reference Contento, Manning and Shannon 38 ), it is stated that effects of school-based nutrition education programmes on attitudes were generally positive but inconsistent. Furthermore, it is stated that up to 50 classroom hours of exposure are required to achieve stable improvements( Reference Contento, Manning and Shannon 38 ). The implementation of three or four lessons of Taste Lessons might explain the weak and inconsistent effects on attitude we found in our study.

In our study, we did not find any effect of Taste Lessons on children’s emotion. In contrast, at the second follow-up measurement, the intervention group showed a higher decrease on enjoyment of eating healthy and a variety of foods than the control group. At baseline, children in the intervention group showed a significantly higher score on emotion compared with the control group. This difference remained significant one month after the intervention. Six months after the intervention, however, the higher score in the intervention group dropped to a score similar to that of the control group at all three moments of measuring. A possible explanation for this decrease in emotion in the intervention group at the second follow-up measurement might be that a habituation process took place( Reference Brickman, Coates and Janoff-Bulman 39 ) or the absence of new stimuli to maintain positive feelings towards the behaviour. Positive feelings about a certain behaviour might fade to neutral feelings over time. Since no other evaluation studies have assessed the effect on emotion, more research needs to be conducted for exploring the role of emotion in changing children’s eating behaviour.

In the present study we found short-term effects of Taste Lessons on children’s subjective norm of the teacher and parents to taste unfamiliar foods. Similar results were found in the evaluation study of High 5. In the latter study, a significantly higher increase in the children’s perceived social norm of the teacher towards eating fruit and vegetables one year after baseline was found in the intervention group compared with the control group( Reference Reynolds, Franklin and Binkley 29 ). There was also a significantly higher increase in the children’s perceived social norm of the family two years after baseline, compared with the control group. To our knowledge, other evaluation studies of school-based nutrition programmes did not assess subjective norm of classmates, teachers and parents. Social influence is, however, identified as an important factor in the development of children’s food preferences and eating behaviour( Reference Birch 11 , Reference Contento 15 , Reference Westenhoefer 40 ). The observed effect on children’s subjective norm of their teacher establishes that children feel pressure to perform the desired behaviours focused on in class.

Implications for (sustained) behavioural change

As the present study shows positive effects of Taste Lessons on behavioural determinants, such as knowledge, subjective norm and intention, the programme might contribute to behavioural change in the longer term. A review of European school-based nutrition intervention programmes revealed that 76 % of the programmes were able to show improvements in children’s eating pattern, with a duration varying from two weeks to five years. Even stronger effects were found among multi-component interventions( Reference Van Cauwenberghe, Maes and Spittaels 41 ). However, the results of our study showed that only the effect on knowledge remained significant in the new school year. Short-term effects on other determinants did not sustain over a longer period of time. The limited number of implemented lessons might explain these effects. Elementary schools are not obliged to implement nutrition education in the Netherlands; this type of education is optional. A more intensive implementation of Taste Lessons in subsequent years, also in combination with other school activities and a strong support platform, might be required to achieve sustainable effects on behavioural determinants. As they play a key role in the development of healthy eating behaviour of children, also parents should be involved in the programme to reach improved eating behaviours in the long term.

Conclusions

Results show that a partially implemented one-year ‘Taste Lessons’ programme demonstrated small but statistically significant short-term effects on increasing the number of foods known and tasted, and on knowledge, subjective norm of the teacher and intention in relation to taste acceptance and healthy eating behaviour. Full and repeated implementation of Taste Lessons in subsequent years might result in larger effects.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors like to thank the national coordination team of Taste Lessons for providing information on the programme and assisting with the recruitment of schools for the study; and the children and teachers for their participation. Financial support: This work was financially supported by the Ministry of Economic Affairs of the Netherlands, who approved the study design but had no role in the analysis and writing of this article. Conflict of interests: None. Authorship: M.C.E.B.-F. was responsible for formulating the research questions, designing the study, collecting and analysing the data, and writing the article. A.H.-N. and P.v.t.V. participated in formulating the research questions and designing the study, and assisted with analysing the data and writing the article. R.-J.R. and H.J.M. assisted with writing the article. Ethics statement: Ethical approval was not required.