Among the determinants for food intake in children that are often reported are gender, age and socio-economic position(Reference Vereecken, Bobelijn and Maes1–Reference Paulus, Saint-Remy and Jeanjean3). Healthy foods such as fruits and vegetables are found to be consumed more often in girls, in relatively younger age and with a higher socio-economic position of the family. Another important determinant is the parent’s food consumption. A parent–child link for food intake including vegetables and fruits as well as sweets has been described(Reference Longbottom, Wrieden and Pine4–Reference Hanson, Neumark-Sztainer, Eisenberg, Story and Wall6). Children, as a matter of course, tend to eat more of what is available in the household(Reference Bere and Klepp5, Reference Hanson, Neumark-Sztainer, Eisenberg, Story and Wall6). The food intake of the parents, in turn, can be affected by several factors. Socio-economic position is a well-known factor, with a healthier food intake pattern in higher socio-economic groups(Reference Bere and Klepp5, Reference Irala-Estevez, Groth, Johansson, Oltersdorf, Prattala and Martinez-Gonzalez7).

Psychological factors may also be important in understanding health behaviours, including patterns of food intake. A psychological construct of eating behaviour such as cognitive restraint has been related to a higher intake of fruits and vegetables(Reference Beiseigel and Nickols-Richardson8). We found little research on other aspects of eating behaviour in relation to food intakes. Emotional eating implying eating in response to negative emotions could be important for understanding the consumption of food for comfort. Emotional eating has been linked to a higher intake of sugar in girls in one study(Reference Striegel-Moore, Morrison, Schreiber, Schumann, Crawford and Obarzanek9), but more knowledge is needed in this area. Emotional eating in combination with negative life events has furthermore been associated with weight gain(Reference van Strien, Rookus, Bergers, Frijters and Defares10). External eating implying eating as a reaction to external food cues has been linked to more positive attitudes towards different types of foods(Reference Wardle, Marsland, Sheikh, Quinn, Fedoroff and Ogden11). External eating is of relevance considering the food exposure in today’s Western societies. Unhealthy foods are usually exposed more frequently than healthy foods, and a greater sensitivity to external food cues could therefore affect food intake towards unhealthier eating.

Self-esteem could also be important in relation to food intakes. A related concept such as self-efficacy has been linked to a higher fruit and vegetable consumption(Reference Steptoe, Perkins-Porras, McKay, Rink, Hilton and Cappuccio12, Reference Brug, Lechner and De Vries13). Self-efficacy is a component in models predicting health-related behaviour(Reference De Vries, Dijkstra and Kuhlman14), and it means the confidence in one's ability to modify behaviour, for example, eating patterns in a desired direction. Self-esteem implies a trust in one's capacity to manage life in general and within specific domains, and may therefore be of importance for health behaviour. Global self-worth according to the Harter Self-Perception Profile has, in prior literature, been negatively associated with overweight in girls(Reference Burrows and Cooper15) and high-risk behaviours such as higher alcohol consumption(Reference Araujo and Wong16). Body weight is, of course, also essential to consider in eating styles, although there are no consistent results in this area(Reference Togo, Osler, Sorensen and Heitmann17).

Measuring the total food consumption in terms of energy intake is known to pose many methodological problems(Reference Lichtman, Pisarska, Berman, Pestone, Dowling, Offenbacher, Weisel, Heshka, Matthews and Heymsfield18). In the present study, we focus on the frequency of food intake patterns related to the daily consumption of fruit and vegetables as well as sweets and soft drinks. According to the literature, vegetable and fruit consumption is an important marker of a healthy eating style, also being related to biological outcomes(Reference Aranceta, Perez-Rodrigo, Ribas and Serra-Majem19–Reference Djuric, Ren, Mekhovich, Venkatranamoorthy and Heilbrun22). Sweets and sweetened beverages have, on the other hand, been suggested as markers of an unhealthy or ‘Western’ eating style(Reference Aranceta, Perez-Rodrigo, Ribas and Serra-Majem19, Reference Rashidkhani, Akesson, Lindblad and Wolk21).

The psychological factors described above could affect the food choices of parents and their children. These factors will be investigated for parents and children’s intake of vegetables, fruits, sweets and soft drinks, respectively, as a first step. The links between psychological factors and food intake may differ for men and women as well as for parents and children. To find the most important characteristics that could explain the eating style of the children, a second step is to test the parents’ food intake and eating behaviour as well as the child’s own characteristics in relation to their food intake.

We hypothesised that restrained eating and self-esteem are related to healthier food intakes seen in fruit and vegetable consumption, in contrast to emotional and external eating. Understanding various types of food intakes is essential for more effective public health interventions that take people's motivating forces and perceived barriers into account. If children’s food intakes are strongly influenced by the characteristics of their parents, this would furthermore emphasise the role of the parents and the need to direct information or interventions towards them.

Methods

Sample and procedure

The PITCH (Parental Influences on Their Children’s Health) dataset was created by a record linkage between several Swedish national registers in the year 2000 (the Medical Birth Register, the Military Service Conscription Register and the Statistics Sweden’s Multi-Generation Register). From the database, boys and girls born in Sweden during 1988 and 1989, whose biological parents were born in a Scandinavian country, living in Sweden and alive during 1999, were selected. The study design included three weight groups among the parents: (i) an overweight father and normal-weight mother; (ii) an overweight mother and normal-weight father; and (iii) both parents being normal weight. This implies that the mean BMI of the parents are higher than in the general Swedish population. The response rate was 33·5 %. The sample consists of 1795 mothers, 1471 fathers and 1441 of their children (731 girls and 710 boys) for whom the data from both parents were complete. The children were all approximately 12 years old (Table 1) at the time of the data collection for this study. Different questionnaires adapted for adults and children were sent to parents and children separately, accompanied by a letter with information. According to the information in the letters, the questionnaire should be completed by the parent or child on their own. Analyses of missing data due to non-participation or incompletely filled questionnaires showed no difference in BMI for the parents, but a higher proportion of well-educated parents among the respondents(Reference Eriksson, Nordqvist and Rasmussen23).

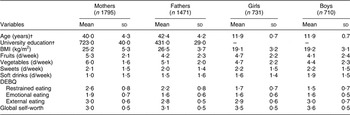

Table 1 Sociodemographic data, body size, food intake and DEBQ scores for parents and children

DEBQ, Dutch Eating Behaviour Questionnaire.

†Data are n and %.

Food intake

The assessment of food intake was performed using an FFQ of the type inquiring only about frequencies of food types without specification of portion size(Reference Khani, Ye, Terry and Wolk24), but in a new version adapted for the study. This FFQ covered eleven types of foods: fruits, vegetables, sweets, sugar-sweetened soft drinks, artificially sweetened soft drinks, low-fat milk, whole-fat milk, potato chips, French fries, dark bread and white bread. The following typical healthy and unhealthy foods were selected from this list: fruits, vegetables, sweets and soft drinks. All kinds of sweets were assessed as one category, using the Swedish word for ‘sweets’ that includes all sorts of candies and chocolate. Soft drinks with sugar and with artificial sweeteners were collapsed into one soft drink category, as they were both considered as markers of unhealthy foods. Artificially sweetened soft drinks add no nutritional value. Furthermore, it has been hypothesised that a predisposition to sweet taste is maintained by an exposure to sweetened drinks(Reference Beauchamp and Moran25), which may be the case for artificial sweeteners as well. Artificially sweetened soft drinks were therefore included in the overall soft drink measure indicating an unhealthy food pattern. Collapsing both types of soft drinks into one variable also gave a better distribution of the data, as soft drink consumption was rather uncommon. Food intakes were measured as consumption of the respective food alternatives in number of days during the last week. The alternatives were no intake, 1 d, 2 d, 3–4 d, 5–6 d and every day. To enable data on an interval scale, these alternatives were coded as 0, 1, 2, 3·5, 5·5 and 7, respectively. The numerical range for the food intakes is thus 0–7, as the food could have been consumed from none to all 7 d of the week.

Body weight and height

Body weight and height for adults were self-reported and constituted the most recent weights, whereas the weights from the national databases were past weights and not used for the analyses in this study. Body weights and heights for the children were collected from the school health records or, if the date of measurement differed more than ±6 months from the date when the children answered the questionnaire, from the questions answered by the parents. The mother’s information about the child’s body weight and height was then used, and if this was not available, the father’s information about the child was used. The height and weight data were collected from school health records for 49 % of the children, from the mother for 47 % and from the father for 4 %.

Eating behaviour

Eating behaviour was measured using the Dutch Eating Behaviour Questionnaire (DEBQ)(Reference van Strien, Frijters, Bergers and Defares26), which consists of thirty-three individual items that form subscales for Restrained Eating, Emotional Eating and External Eating. The numerical ranges for the DEBQ scales are 1–5. A higher score represents a more pronounced level of the eating behaviour measured with the scale.

The DEBQ has previously been used in a sample of around 10 000 Dutch adolescents aged 11–16 years (mean age 13 years)(27). The psychometric properties for the DEBQ in this age group were good in terms of Cronbach’s α (restrained eating: 0·92, emotional eating: 0·92, external eating: 0·84) and a factor analysis that confirmed the factor structure observed in adults for the three scales.

Self-esteem

Self-esteem was measured according to a model proposed by Harter(Reference Harter28), using the Harter Self-Perception Profile for Adults (SPPA)(Reference Messer and Harter29) for the parents, and the Harter Self-Perception Profile for Children (SPPC)(Reference Harter30, Reference Wichstrom31) for their children. The SPPA (thirty individual items) and SPPC (thirty-five individual items) contain several subject-specific subscales in addition to a global self-worth scale. The global self-worth scale was used in our analyses. The numerical range for this score is 1–4. A higher score represents higher self-worth.

Education

The parents’ educational level was self-reported as an item with six alternative levels, ranging from less than 9 years of primary school education to 3 or more years of university education. Education was recoded into a dichotomous variable with the categories ‘college/university education’ and ‘no college/university education’.

Statistical analysis

Associations between food intake patterns in parents and children and their BMI, DEBQ scores and global self-worth score were analysed using partial correlations controlling for age and education of the parents. The partial correlations between children’s food intake patterns and BMI were adjusted for their age in addition to the age and education of the parents, as there was some variability in age when children’s heights and weights were measured or reported.

To find the most important explanatory factors or predictors of food intake, in a second step we tested the independent variables that were significant at P level <0·05 (according to the initial correlations) in stepwise linear regression models of food-intake frequencies. This meant regression models for intake of fruit, vegetables, sweets and soft drinks for mothers, fathers, girls and boys. For the parents, their BMI, eating behaviour and self-esteem were considered as potential predictors. In the models for the children, the BMI, food intakes and eating behaviour of the parents were considered as potential predictors, besides the characteristics of the children themselves (children’s BMI, eating behaviour and self-esteem). The parent’s age and education were controlled for by including them in the stepwise procedures (maternal age, paternal age, maternal education and paternal education).

The stepwise linear regression models were set at P-in 0·05 and P-out 0·10. From the models derived in the stepwise procedures, the one with the highest explaining value (R 2) that did still add at least 0·01 in R 2 to the R 2 for the preceding model, i.e. increased the explained variance in outcome variable by at least 1 %, was chosen as the best model and hence presented. However, if the last variable to be included in the model was age or education that was not considered to provide new information, the preceding model was chosen to be presented.

In the analyses for mothers and fathers, the complete dataset was used. In the analyses of the children’s food intakes, only the children with data from both parents were included in the analyses, as the mother's as well as father's characteristics should have the same probability to influence the child’s food intake.

Differences in strengths for correlations stratified for education were analysed using a test for significant differences between independent correlations(Reference Howell32). For the statistical analyses the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS for Windows) version 13.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used.

Results

General results

Sociodemographic characteristics and mean values for the food items and the psychological variables are presented in Table 1. Considering the healthy foods, vegetables had been consumed during all 7 days by 65 % of the adult women, 42 % of the men, 37 % of the girls and 32 % of the boys. Fruits had been consumed during all 7 days by 51 % of adult women and 30 % of the men, by 38 % of the girls and 28 % of the boys. Looking at the unhealthy foods, sweets had been consumed during all 7 days by 3 % of the women, boys and girls, and by 2 % of the men. The corresponding numbers for soft drinks was 3 % for women, men and boys, and 1 % for girls.

Correlates for food consumption

The correlations between food intake and the variables under study are given in Table 2. With higher restrained eating, a more frequent consumption of fruits and vegetables was more likely for the adults, whereas less restraint was associated with a more frequent consumption of sweets, in particular for boys. External eating was in particular related to sweet consumption, for adults as well as children. Emotional eating was associated with a food style with sweets and soft drinks, apparent for women and girls. Self-esteem according to the global self-worth scale showed association with frequency of intake of vegetables among mothers, fathers and boys (P < 0·01).

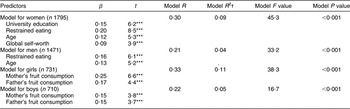

Table 2 Correlations for food intake and psychological characteristics among 1795 mothers, 1471 fathers, 731 girls and 710 boys

W, women; M, men; G, girls; B, boys; DEBQ, Dutch Eating Behaviour Questionnaire.

Significance: *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01, ***P < 0·001.

†Partial correlations controlling for the parent's age and education.

‡Children's BMI controlled for the child's age in addition to the parent's age and education.

Associations between parents and children

The correlations between the characteristics of the parents and the children’s food intakes are shown in Table 3. As can be seen, vegetable and fruit consumption in parents is clearly related to the same food types in their children. Correspondingly, consumption of sweet foods and soft drinks in parents is associated with higher frequencies of these food items in their children. The other parental characteristics were of minor importance for the children’s food intakes.

Table 3 Correlations between the children’s food intake and the parent’s characteristics among 1795 mothers, 1471 fathers, 731 girls and 710 boys

M, mother; F, father; DEBQ, Dutch Eating Behaviour Questionnaire.

Significance: *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01, ***P < 0·001.

†Partial correlations controlling for the parent's age and education.

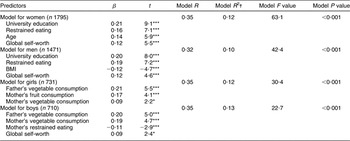

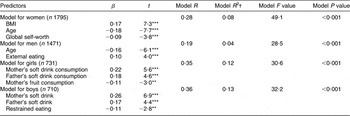

Multiple linear regression analyses of food consumption

The linear regression analyses of food consumption are displayed in Tables 4–7. The regression models for healthy food consumption seen in Tables 4 and 5 included different characteristics for adults and children. For adults, important psychological explanatory variables for higher intake (frequency) of fruits and vegetables were more restrained eating and higher self-worth. A higher education and age did, however, contribute to the explanation of the consumption of these foods. The variance in vegetable consumption explained by these factors reached about 10–13 %. For the children, it was instead the parent’s healthy food intake that explained a higher consumption of fruits and vegetables. For the boys, the mother’s restrained eating and the boy’s self-worth were additional factors associated with their vegetable consumption.

Table 4 Predictors for consumption of fruits as estimated by multiple linear regression analysis

Four separate models fitted for women, men, girls and boys, respectively. All models adjusted for age and education but the corresponding estimates are only presented if significantly associated with the outcome at P = 0·05.

Significance: *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01, ***P < 0·001.

†Proportion of total variance in outcome variable explained by the whole model.

Table 5 Predictors for consumption of vegetables as estimated by multiple linear regression analysis

Four separate models fitted for women, men, girls and boys, respectively. All models adjusted for age and education but the corresponding estimates are only presented if significantly associated with the outcome at P = 0·05.

Significance: *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01, ***P < 0·001.

†Proportion of total variance in outcome variable explained by the whole model.

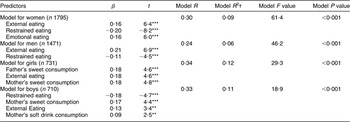

Table 6 Predictors for consumption of sweets as estimated by multiple linear regression analysis

Four separate models fitted for women, men, girls and boys, respectively. All models adjusted for age and education but the corresponding estimates are only presented if significantly associated with the outcome at P =0·05.

Significance: *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01, ***P < 0·001.

†Proportion of total variance in outcome variable explained by the whole model.

Table 7 Predictors for consumption of soft drinks as estimated by multiple linear regression analysis

Four separate models fitted for women, men, girls and boys, respectively. All models adjusted for age and education but the corresponding estimates are only presented if significantly associated with the outcome at P = 0·05.

Significance: *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01, ***P < 0·001.

†Proportion of total variance in outcome variable explained by the whole model.

As seen in Table 6, sweet consumption in adults was best explained by a model including all or some of the DEBQ eating behaviour domains: more external and emotional eating and less restrained eating. Corresponding to the results for healthy food intakes, intake of sweets in the children was best explained by the parent’s sweet intake, and in addition by the children’s external eating. Soft drink intake in the children could likewise be best explained by the parent’s soft drink intakes (Table 7). Among adults, age and higher education were inversely associated with soft drink consumption. A higher BMI was furthermore associated with higher soft drink consumption for women, and external eating for the men. As for the models for healthy food intake, the models for unhealthy food intake reached at the most 11–13 % of the variance explained, seen for the children.

Different levels of education

As there was a higher proportion of well-educated parents among the respondents, the analyses were repeated with the sample stratified according to the level of education. Of the significant links reported in Table 2, only one correlation differed significantly (P < 0·01) depending on the level of education: The fathers with university education showed a stronger negative correlation for vegetables and BMI (r = −0·19, P < 0·001), than the non-significant correlation seen for fathers with lower education (r = −0·02, NS). There were no significant differences in the correlations for food intake and psychological variables reported as significant associations for the whole sample in Table 2.

The multiple linear regressions for intake of fruits and vegetables in parents (Tables 4 and 5) were also stratified for level of education as a university education was a predictor in these models. The β-estimate for the psychological predictor Restrained Eating in these models was similar for the fathers with different levels of education. For the mothers, the β-estimate for fruits as well as vegetables was 0·09 units higher among those with no university education: The β-estimate for restrained eating in the model for fruit intake was 0·23 for mothers with no university education, v. 0·14 for those with university education. The β-estimate for restrained eating in the model for vegetable intake was 0·19 for mothers with no university education v. 0·10 for those with university education.

Discussion

In the present study, we investigated psychological factors associated with the consumption of fruits, vegetables, sweets and soft drinks in parents and their children, also taking the parent’s characteristics into account when investigating the children’s food intakes. The food intakes were measured as consumption of the food items in number of days during the last week, and did not take portion sizes into account. Although this is a crude measure of food intake, weekly food frequency can be regarded as an indicator of food intake patterns. Such a measure can be an alternative to more detailed dietary assessments in large-scale studies as it is time-sparing and easily administered.

Education

The impact of a higher education on purchasing more vegetables and fruits in the household is known from prior literature(Reference Ricciuto, Tarasuk and Yatchew33). In accordance with previous research, our results showed positive associations of intake of vegetables and fruits with level of education and age of the parents. With higher education, the knowledge and awareness of healthier eating could be more common, and a higher income as well as social habits can also affect food choices. In this study, we were interested in exploring psychological dimensions that could extend our understanding of the complex mechanisms behind food choices in families with children.

Restrained eating

Restrained eating was associated with more fruit and vegetable consumption in adults, and with a lower intake of sweets in parents and children, as hypothesised. However, the benefit of higher restraint over eating is not obvious from the literature. Although restrained eating behaviour increases with successful weight control as seen in obesity treatment(Reference Karlsson, Hallgren, Kral, Lindroos, Sjöström and Sullivan34), restraint has also been suggested as a predecessor of more problematic eating with cravings for unhealthy foods(Reference Tuschl35). Still, others have also found restrained eating (according to various questionnaires) to be related to a higher intake of fruits and vegetables in adults(Reference Beiseigel and Nickols-Richardson8, Reference de Lauzon, Romon, Deschamps, Lafay, Borys, Karlsson, Ducimetière and Aline Charles36). Restrained eating as measured by the DEBQ does seem to represent a relatively more successful dieting behaviour component of restraint(Reference Laessle, Tuschl, Kotthaus and Pirke37). However, due to the cross-sectional nature of the dataset analysed, the fact cannot be excluded that the restraint implies dieting attempts, and the healthy foods reported may reflect the dieting intentions rather than foods actually consumed.

For the children there were no associations between restrained eating and fruit and vegetable intakes, only an inverse association was found with the intake of sweets. Restrained eating may have different meanings for adults and children. Other researchers have reported that adults and teenagers differ with respect to associations of food intake patterns with restrained eating that are consistent with our findings, implying a negative correlation to energy-dense foods in teenagers, rather than the association with a healthy eating style that was seen in adults(Reference de Lauzon, Romon, Deschamps, Lafay, Borys, Karlsson, Ducimetière and Aline Charles36). Children 11–12 years of age and adolescents may not have attained the maturity and knowledge to restrict their diet in such a way that is not only low in calories but also healthy and of good nutritional value. Higher restrained eating in children has also been associated with poorer cognitive performance(Reference Brunstrom, Davison and Mitchell38), which could indicate a poor nutritional status.

Self-esteem

Higher self-esteem was yet another factor of importance for healthy eating as hypothesised and remained when education was controlled for. Higher self-esteem may be associated with a trust in own capacity to adopt a healthy eating pattern that can affect food choices. Having a higher sense of self-worth can furthermore imply caring more about the personal health and well-being, leading to healthier food intakes.

External and emotional eating

When it comes to external and emotional eating, less is known about the associations to food intakes. External eating was an important explanatory variable for sweet intake in adults and also associated with sweet intake in children. External eating was furthermore associated with soft drink consumption, although those associations were weaker. External eating implies being more prone to eating in response to external food cues and our results should be regarded in the context of the food culture in the Western society. There are economic interests in marketing processed foods high in sugar and fat, such as sweets, in our society(Reference Nestlé39). The advertising and marketing includes providing tempting stimuli, increasing the variety of tastes and making the packet sizes larger. These are all stimuli that influence our senses and will therefore, in particular, affect the person who is more prone to external eating. Foods high in sugar are also perceived as more palatable, which can affect individuals prone to external eating more as taste is one of the aspects in external eating.

We found an association between emotional eating and sweet intake to be foremost in women, and to a lesser extent in girls. Emotional eating means to eat for comfort, as a response to various negative and painful emotions. The psychological aspects imply eating as a compensation, and as a way to avoid emotions that would be painful or unpleasant to experience fully. According to theories, an inadequate early mother–child interaction can also cause an inability to distinguish among various internal states, be it emotions or hunger(Reference Bruch40). Sweets could be perceived as especially soothing in eating for comfort, due to the pleasurable and rewarding aspects that are usually linked to sweets. The possibility of additional rewarding and soothing neuro-chemical effects of sweets cannot be excluded(Reference Dallman, Pecoraro and la Fleur41, Reference Cooper, Jackson and Kirkham42). The association between sweets and emotional eating was foremost in women and girls. Sweet taste may be more physiologically rewarding for women, or the use of sweets for comfort may be more accepted by women and be a learned behaviour in our culture. The need for foods such as sweets for comfort is a psychological factor that can be very difficult to abstain from, despite conscious ambitions, and should thus be considered in people’s food choices.

Intake of soft drinks in adults was partly explained by the sociodemographic characteristics and external eating for the men. In addition, the correlations showed an eating behaviour pattern similar to the one seen in sweet intake, but weaker.

Children’s food intake

The most important explanatory factors for the children’s food intakes were the food intakes of the parents. In addition, the intake of sweets was linked to external eating, and in the correlations also to unrestrained eating for boys and emotional eating for girls.

According to a review of prior literature, the majority of the studies in the area show that parental fruit and vegetable intakes have a positive association with children’s intakes(Reference Rasmussen, Krolner, Klepp, Lytle, Brug, Bere and Due43), and an association for chocolate(Reference Longbottom, Wrieden and Pine4) and soft drinks(Reference Grimm, Harnack and Story44) have also been found. It seems reasonable that children tend to eat more of the foods their parents eat as this is exposed to them and available in their homes.

The fact that the food intake of the parent is apparently essential for the child’s food intake can evoke a greater sense of responsibility and insight among parents that they are able to influence their children’s food intake towards a healthier pattern. Furthermore, the children’s food intake was less affected by psychological factors than among adults, and may thus be easier to alter. Information, advice and support to parents as regards their possibilities as well as responsibility to influence their children’s health behaviour in a positive direction are important. Self-efficacy among parents may be crucial in this context(Reference Steptoe, Perkins-Porras, McKay, Rink, Hilton and Cappuccio12, Reference Brug, Lechner and De Vries13). The parents have great opportunities in providing healthier and less-unhealthy foods at home, and serving as a role model in food habits. Advice to increase the availability and accessibility of fruit and vegetables in the child’s daily environments has been suggested as an intervention(Reference Blanchette and Brug45).

Limitations

To measure the intake of fruit and vegetables in children and adults is difficult(Reference Andersen, Bere, Kolbjornsen and Klepp46, Reference Kristjansdottir, Andersen, Haraldsdottir, de Almeida and Thorsdottir47), and social desirability is one sort of bias that may have caused overestimations in reporting consumption of fruits and vegetables and underestimations of sweets and soft drinks. However, the fact that up to 70 % of the children did not have vegetables or fruits on all days of the last week does not seem to indicate that social desirability bias is a major problem in the present study. Furthermore, parent–child associations found for food intakes may potentially be biased as parents may have assisted their children to complete the questionnaires despite instructions that the children should complete their questionnaires on their own. Another limitation with the study was the low response rate of 33·5 %, with a higher proportion of well-educated parents among respondents. This means fruit and vegetable intake that is known to be linked to a higher education was likely more frequent than in the general population. The food intake patterns described in the study may not be representative for the general Swedish population of families with children 12 years of age, due to the higher response rate among well-educated families. However, our results showed that the associations between food intake patterns and psychological dimensions of eating behaviour did not differ substantially by social position as measured by level of education.

Conclusion

We conclude that psychological factors were associated with the intake of some healthy and unhealthy foods in a meaningful pattern for adults as well as children, and also that these factors are more important for the adults. Being more sensitive to external food cues can imply proneness for unhealthy food consumption in our society, whereas more restrained eating implied healthier food choices, in particular for adults. Eating for comfort was indeed associated with the consumption of sweets, as popular belief claims, but mainly among women and girls. Sweet intake was the food style that could be best understood in terms of the psychological constructs of eating behaviour. The most important factors for the children’s intake of healthy and unhealthy foods were clearly the food intakes of their parents.

Acknowledgements

Conflict of interest: We have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding support: This study was supported by a grant to Finn Rasmussen from the Swedish Council for Social Research (grant number F0123/2000).

Authors’ contributions: K.E. developed the hypotheses for this specific study, performed the statistical analyses and drafted the paper. S.T. participated substantially in the development of questionnaires and in the selection and adjustment of measurement scales and creation of the PITCH database. F.R., principal investigator of the PITCH study, provided input to the analytic work, revision of the draft and the final version of the paper. The contributions of Per Tynelius, with regard to sampling and creation of the database, are greatly appreciated.