The Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 (FMLA) requires that U.S. workplaces with at least 50 employees provide 12 weeks of unpaid job-protected parental leave, as well as unpaid leaves for employees with serious illnesses and those caring for seriously ill relatives.Footnote 1 The rights promised to parents are quite modest, compared to other countries' leave benefits (Reference Gornick and MeyersGornick & Meyers 2003; Reference Kelly and Pitt-CatsouphesKelly 2005), and quite easy to administer compared to other employment rights in the United States. Yet this analysis reveals that at least one-quarter of covered workplaces were violating the parental leave requirements of the FMLA when surveyed four years after the law's implementation. What explains organizational noncompliance with the FMLA's parental leave provisions? I examine this question using a 1997 survey of almost 400 U.S. workplaces and 40 semi-structured interviews with managers.

This article advances the field in two ways. First, I extend neo-institutional theory to explain noncompliance. Previous research has documented how organizations respond to the legal environment, often by adopting new policies and programs that are thought to signal attentiveness to or compliance with the law (e.g., Reference DobbinDobbin et al. 1993; Reference EdelmanEdelman 1990, Reference Edelman1992; Reference KellyKelly 2003; Reference Sutton and DobbinSutton & Dobbin 1996). By examining noncompliance, I investigate which organizations are not responsive to a seemingly clear legal requirement and consider the limits of institutional pressures for advancing social change. I also propose connections between neo-institutional theory and research on deviant organizational cultures.

Second, I theorize and empirically examine different forms of noncompliance. Most previous research uses a dichotomous measure of compliance versus noncompliance (e.g., Reference Ashenfelter and SmithAshenfelter & Smith 1979; Reference Ehrenberg and SchumannEhrenberg & Schumann 1982; Reference Gray and ShadbegianGray & Shadbegian 2005; compare Reference SimpsonSimpson 1986; Reference VaughanVaughan 1999). I analyze different forms of noncompliance with a single law, contrasting organizations that do not provide any leave with those that provide less than the 12 weeks of leave required by the FMLA. I also analyze maternity leaves (for mothers) and paternity leaves (for fathers) separately, despite the fact that the FMLA is deliberately gender-neutral in its language. I find that there are different predictors of an outright lack of leave as compared to an illegally short leave, as well as important differences across the models for maternity leave and paternity leave. Like recent efforts to identify and explain different trajectories of offending among individuals (e.g., Reference Moffitt and CullenMoffitt 2008), this work demonstrates the value of disentangling the category of noncompliance rather than only contrasting those who abide by and violate the law.

Specifically, I contend that some forms of noncompliance reflect a failure to update existing policies and practices. Previous theories of noncompliance focus too much on strategic decisions and too little on the ways that entrenched policies and practices sometimes turn into noncompliance—without organizational decisions or actions—when the legal environment changes. The institutional perspective on noncompliance helps explain illegally short leaves—what might be called partial compliance—in particular. Predictions from a rational choice perspective and deviant culture perspective fare well in explaining an outright lack of family leave.

The qualitative evidence confirms that the failure to update old policies and practices is caused both by unintentional oversight and by ambivalence about the legal changes. Unintentional noncompliance is certainly problematic; however, different enforcement efforts may be appropriate for addressing distinct forms of noncompliance. “Sins of omission,” which are more common in smaller organizations and those that lack human resources professionals, play a strong role in noncompliant maternity leaves. Ambivalence about the law's support of men's caregiving encourages short paternity leaves even when 12 weeks of leave are officially available.

The FMLA and Its Precursors

Many organizations already had maternity leave policies and related benefits in place before the FMLA was enacted in 1993. These policies were adopted in the 1970s and early 1980s in response to changes in sex discrimination law (Reference Kelly and DobbinKelly & Dobbin 1999). Federal regulations and later the Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978 required organizations to treat employees “disabled” due to pregnancy or childbirth the same way they treated other workers who were physically unable to work (Reference EdwardsEdwards 1996; Reference VogelVogel 1993). For example, organizations that allowed employees time off if they needed to recover from a heart attack had to do the same for employees recovering from childbirth. In addition, disability insurance policies that provided partial pay to employees while they were on leave had to cover “pregnancy-related disabilities” as well (Reference Kelly and DobbinKelly & Dobbin 1999). Maternity leaves based on this disability analogy were only available to birth mothers, because only birth mothers need time to physically recover from childbirth. The length of those leaves was determined by women's ability to return to work, with a norm of six to eight weeks because that is the average time for a woman's uterus to return to its normal size and position in the body after childbirth.

The FMLA deliberately broadened access to leaves to fathers, as well as adoptive mothers, employees caring for a seriously ill relative, and employees dealing with their own health conditions (Reference ElvingElving 1995). The text of the statute emphasizes the gender neutrality of the new rights, referring to fathers' caregiving in positive terms, recognizing the rise of dual-earner households, and arguing that “employment standards that apply to one gender only have serious potential for encouraging employers to discriminate against employees and applicants for employment who are of that gender” (29 USCS § 2601). More broadly, the FMLA challenges institutionalized assumptions about what employers and employees should do when work and family obligations conflict. As Reference AlbistonAlbiston (2005:13) notes,

The law erodes certain taken-for-granted expectations about work, such as unbroken attendance as the measure of a good worker and employer control over work schedules. It also undermines traditional ideologies about the gendered division of labor in the family by requiring work to accommodate family needs on a gender-neutral basis.

Yet research suggests that the FMLA and similar state laws have had fairly minimal effects on women's leave-taking (in part because maternity leaves were common before the FMLA) and no discernible impact on men's use of leaves (Reference BaumBaum 2003; Reference Han and WaldfogelHan & Waldfogel 2003; compare Reference Johnson and DownsJohnson & Downs 2005). The lack of pay provisions in the FMLA discourages men's use of family leave; there is often a greater loss of family income if men take a leave (Reference Gornick and MeyersGornick & Meyers 2003). In addition, men are significantly less likely than women to know they are eligible for FMLA leaves (Reference Baird and ReynoldsBaird & Reynolds 2004; compare Reference Budd and BreyBudd & Brey 2003).Footnote 2 While the law's limited effects are related to its limited coverage, lack of income replacement, and narrow definition of family, the small changes in parental leave utilization since the FMLA may also be related to inadequate implementation of the law by organizations, i.e., noncompliance.

There has been relatively little research on organizational leave policies in the wake of the FMLA, but all the available evidence points to substantial levels of noncompliance. A 2000 survey found that 84 percent of establishments (all covered by the FMLA) reported providing “up to 12 weeks” of leave for all FMLA reasons, leaving 16 percent noncompliant (Reference CantorCantor et al. 2001:5.1). However, because the survey question cued respondents about the length of leave required by the law and because the U.S. Department of Labor sponsored the study, some organizations may have reported compliant policies when they normally provided shorter leaves. A 2008 study of 1,100 private sector organizations asked about “the maximum length of unpaid or paid job-guaranteed leave” without cuing respondents about the length of leave required by the FMLA. These data suggest that 19 percent of organizations are still noncompliant with the FMLA, but this figure is likely low because 30 percent of respondents did not answer all the questions about FMLA-covered leaves (Reference GalinskyGalinsky et al. 2008:6). Reference Gerstel and ArmeniaGerstel and Armenia (2009) recently used these data to estimate that between 28 and 44 percent of organizations are noncompliant, depending on how one treats the cases with missing data. Although the data utilized here were collected in 1997, recent studies find continued and significant noncompliance.

An Institutional Perspective on Noncompliance

Neo-institutional theory claims that organizational actors make decisions based on a drive to demonstrate the organization's legitimacy as a social actor, as well as to maximize financial performance. Research has established that organizations respond—to varying degrees—to the institutional environment, which includes “coercive pressures” such as regulations and laws, “normative pressures” often set by professions, and “mimetic pressures” to imitate peer organizations that appear legitimate or successful (Reference DiMaggio and PowellDiMaggio & Powell 1983; Reference ScottScott 2001). Scholars of law and organizations have shown that so-called coercive pressures are more complex than the term coercion implies. In the arena of U.S. employment law, at least, “the law” rarely dictates organizational policies and practices in a simple, top-down manner (Reference DobbinDobbin et al. 1993; Reference EdelmanEdelman 1990, Reference Edelman1992; Reference Edelman and UggenEdelman, Uggen, et al. 1999; Reference Kelly and DobbinKelly & Dobbin 1999; Reference Suchman and EdelmanSuchman & Edelman 1996; Reference Sutton and DobbinSutton & Dobbin 1996). Instead, employers, professionals such as human resources managers and attorneys, courts, regulators, and other interested actors interact to determine what will count” as compliance with new laws. Once new policies and practices are accepted as signals of compliance, large numbers of organizations adopt them, and eventually courts and other legal actors begin to defer to these management practices when assessing compliance (Reference EdelmanEdelman 2004; Reference Edelman and UggenEdelman, Uggen, et al. 1999).

Attentiveness to the Legal Environment

By examining noncompliance with the FMLA, I investigate which organizations are not responsive to changes in the legal environment. My first claim is a simple one: The organizational traits that predict responsiveness to the legal environment will be negatively associated with noncompliance. Attentiveness to the legal environment should reduce noncompliance with the FMLA. Research has consistently found that larger organizations and public sector organizations are quicker to adopt the policies, practices, and structures that signal compliance with anti-discrimination laws and regulations (e.g., Reference EdelmanEdelman 1990, Reference Edelman1992; Reference Sutton and DobbinSutton & Dobbin 1996). Hypotheses 1 and 2 (see Table 1) state that larger organizations and public sector organizations will be less likely to violate the FMLA's parental leave requirements. This literature also views personnel or human resources professionals as key conduits of institutional pressures because they are charged with monitoring the legal environment (e.g., Reference DobbinDobbin 2009; Reference Dobbin and SuttonDobbin & Sutton 1998; Reference Edelman and ErlangerEdelman, Erlanger, et al. 1993). Hypothesis 3 states that organizations with a human resources specialist (i.e., either a department or a member of a professional association) will be less likely to be noncompliant with the FMLA.Footnote 3

Table 1. Hypotheses Regarding Noncompliance with the FMLA

The Continuing Influence of Old Institutions

My second claim emphasizes the social context of organizational actions and the durability of social institutions (Reference Powell and DiMaggioPowell & DiMaggio 1991; Reference MartinMartin 2004; Reference ScottScott 2001) and helps disentangle different forms of noncompliance. Organizations may violate laws by continuing on with existing policies and practices after the state has told them to do things differently. This type of noncompliance does not necessarily reflect a conscious choice. After all, one of the characteristics of institutions is that they are generally self-sustaining and often taken for granted. Instead, noncompliance that reflects a failure to update institutionalized policies or practices may occur unintentionally or with limited planning.Footnote 4 This is quite different from the rational calculation of the benefits and likely costs of noncompliance that is assumed in many studies of noncompliance or corporate crime.

Individuals and organizations regularly face “competing institutions” that ask different things of them (Reference Friedland, Alford, Powell and DiMaggioFriedland & Alford 1991; Reference HeimerHeimer 1999). Competing institutions create openings for change, but they do not ensure it. New laws often signify an official challenge to older institutions; the old way of doing things is denaturalized and delegitimated, and new expectations are laid out explicitly in a new law. Still, the older institutions may win out in some contexts, even in the face of the coercive pressures for change contained in a new law. From this perspective, some forms of noncompliance can be understood as the failed deinstitutionalization of the older institutions.

In this case, previously institutionalized leave policies may foster noncompliance with the FMLA if they are not appropriately updated. Specifically, the disability framework that is encapsulated in the Pregnancy Discrimination Act (1978) and early maternity leaves may lead some organizations to continue to offer six to eight weeks of leave to mothers, although the FMLA now requires 12 weeks of leave to be allowed. Hypothesis 4 states that organizations with temporary disability insurance plans in place are more likely to provide illegally short maternity leaves. While my focus is the legacy of temporary disability policies, one could generalize from this to hypothesize that older organizations will be more likely to be noncompliant with the FMLA (Hypothesis 5). This is consistent with the institutional claim that organizations are imprinted at founding—they adopt the structures and policies considered legitimate at that time—and are unlikely to change in significant ways later on (Reference Stinchcombe and MarchStinchcombe 1965).

While institutionalized organizational policies may affect noncompliance with maternity leave requirements, noncompliant paternity leaves may be related to institutionalized assumptions that men are only minimally involved in caring for infants and institutionalized practices of giving men only a few days off after a birth. Gender scholars have long noted that organizations idealize—and reward—those who will work continuously and as many hours as are requested (e.g., Reference AckerAcker 1990; Reference Moen and RoehlingMoen & Roehling 2005). Obviously, “[this] way of defining the ideal worker is not ungendered. It links the ability to be an ideal worker with the flow of family work and other privileges typically available only to men” (Reference WilliamsWilliams 2000:5). Men realize that it is risky to violate these institutionalized expectations of unfettered commitment to the employer by taking family leaves, reducing their hours, or otherwise signaling their family obligations (Reference CooperCooper 2000; Reference TownsendTownsend 2002). The FMLA can be viewed as an attempt to challenge these institutionalized gender norms by encouraging men to take family leaves (Reference AlbistonAlbiston 2005). However, noncompliance with the FMLA's paternity leave provisions may reflect the continued influence of a more traditional gender regime in some organizations.

Although it has long been claimed that organizations are “gendered,” scholars have paid less attention to empirically explaining variation in gender traditionalism across organizations (Reference BrittonBritton 2000). To begin to address this gap, I explore two organizational traits that may be associated with gender traditionalism: sex composition and previous enactment of gender-neutral work-family policies. Hypothesis 6 claims that organizations with a higher percentage of male workers will be more likely to have noncompliant paternity leaves, although numerical dominance may matter most when women are tokens because then family leaves will be a rare event (Reference Moss KanterMoss Kanter 1977). A recent analysis finds that organizations where women are more than 50 percent of the workforce are less likely to be violating the FMLA provisions in general and more likely to provide paternity leave (Reference Gerstel and ArmeniaGerstel & Armenia 2009). Family leave policies may reflect a broader interest (or lack of interest) in work-life issues on the part of management. Organizations with other work-family policies—such as flextime and pre-tax accounts for dependent care expenses—that are available to both men and women may be more open to recognizing and supporting men's leave rights under the FMLA. Hypothesis 7 states that organizations with more work-family policies are therefore less likely to have noncompliant paternity leave policies.

Deviant Culture Perspective

Regulation scholars have long been interested in the ways that deviance is supported and facilitated by some organizational cultures (Reference BraithwaiteBraithwaite 1984). Scholars have noted that employees are socialized into deviant cultures and that immersion in a deviant culture makes it easier to “normalize deviance” because it is so common. These arguments can be applied to organizations in an organizational field as well as individuals within a company. Doing so suggests links between neo-institutional theory's concept of mimetic isomorphism and the deviant culture perspective. Both perspectives recognize that organizations are affected by their peers' interpretation of the legal environment. If peer organizations are ignorant of the legal requirements, it is more likely that the organizations will remain in the dark. If peer organizations are deliberating violating the law, it is more likely that deviance will be normalized—excused as being what everyone else is doing (Reference ColemanColeman 1998; Reference VaughanVaughan 1996, Reference Vaughan1999). Hypothesis 8 states that organizations in industries where noncompliance is higher will be more likely to be noncompliant with the FMLA.

This literature also suggests that organizations have stable cultures, and that some organizations are “repeat offenders” across different legal domains (Reference Clinard and YeagerClinard & Yeager 1980; Reference Gray and ShadbegianGray & Shadbegian 2005; Reference Shover, Routhe and TonryShover & Routhe 2005). I lack direct measures of organizations' noncompliance with other laws and instead turn to a proxy measure. Because regulatory agencies often target organizations that are believed to be violating the law (Reference Gray and ShadbegianGray & Shadbegian 2005), Hypothesis 9 asserts that organizations that have previously gone through an Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs (OFCCP) compliance review—an audit of the organization's equal opportunity and affirmative action policies—will be more likely to be noncompliant with the FMLA. Alternatively, one could view an earlier OFCCP compliance review as a deterrent that would make organizations more careful about complying with all federal employment laws and therefore discourage noncompliance with the FMLA (Reference LangbertLangbert 1996).

Previous research emphasizes the role of top management in shaping organizational cultures and in determining how organizations will respond to laws (Reference Braithwaite and MakkaiBraithwaite & Makkai 1991; Reference Coglianese and NashCoglianese & Nash 2001). Based on the claim that “top management, particularly the chief executive office, sets the ethical tone” of an organization (Reference Clinard and YeagerClinard & Yeager 1980:60), Hypothesis 10 claims that organizations in which the CEO (or equivalent top executive) is more supportive of work-family issues are less likely to be noncompliant with the FMLA.

Rational Choice Perspective

From a rational choice perspective, organizations are “amoral calculators” (Reference Kagan, Scholz, Hawking and ThomasKagan & Scholz 1984; Reference BeckerBecker 1968), and noncompliance occurs after strategic and deliberate decisions about the relative costs and benefits of complying with or violating a given law. This perspective is dominant among economists (e.g., Reference Ashenfelter and SmithAshenfelter & Smith 1979; Reference Chang and EhrlichChang & Ehrlich 1985; Reference Ehrenberg and SchumannEhrenberg & Schumann 1982; Reference GrenierGrenier 1982) and has also been utilized by many political scientists and criminologists who study noncompliance with a variety of laws and regulations (e.g., Reference Braithwaite and MakkaiBraithwaite & Makkai 1991; Reference KaganKagan et al. 2003; Reference May and SalamonMay 2002, Reference May2004; Reference SimpsonSimpson 1986, Reference Simpson2002). In the case of family leaves, the costs and benefits of compliance and noncompliance will depend on the likely utilization of leaves, the costs of replacing workers, deterrent effects, and the level of financial strain in the organization.

Because women are more likely than men to use parental leaves (Reference Han and WaldfogelHan & Waldfogel 2003), the costs of compliance with the FMLA (and its maternity leave requirements, specifically) rise with each woman of childbearing age. This suggests that organizations with a higher percentage of women workers will be more likely to be noncompliant (Hypothesis 11), in contrast to the institutional hypothesis that organizations with more men will be more likely to violate the paternity leave requirements in particular.

The costs associated with leaves include the lost productivity of the leave-taker and the costs of temporary replacement workers. If leaves are not allowed, though, turnover costs will likely be higher, because workers may quit to meet their family obligations. Because highly skilled workers cost more to replace (Reference Ehrenberg and SchumannEhrenberg & Schumann 1982; Reference Doeringer and PioreDoeringer & Piore 1971), Hypothesis 12 states that organizations with more professional and managerial workers will be less likely to be noncompliant. Previous research has shown that organizations that rely on professional and managerial workers tend to provide more generous family policies (Reference Deitch, Huffman, Hertz and MarshallDeitch & Huffman 2001; Reference Glass and FujimotoGlass & Fujimoto 1995; Reference KellyKelly 2003).

Deterrence theory emphasizes the likely costs of noncompliance, in particular the risk of being caught and the sanctions that a violating organization would face if caught. Under the FMLA, the risk of detection and the severity of sanctions are both minimal. The federal government learns about disputes and possible noncompliance only when employees complain to the Wages and Hours Division of the Department of Labor or file a lawsuit. For example, in fiscal years 2000 to 2005, complaints averaged 3,137 per year, and employers were found to be violating the FMLA in 49 percent of those cases (U.S. Department of Labor 2002, 2005: n.p.). In cases where employers were found to be at fault, employees received an average of about $1600. In cases where employers were found to be at fault, employees received an average of about $ 1,600. Damages are capped at two times an employee's lost wages and benefits, or the costs of alternative care if the employee did not take a leave, plus legal costs. A review of appellate court cases on family leaves heard in the 1990s finds that employers won about 65 percent of the time (Reference WisensaleWisensale 1999).

While all the organizations in this study were subject to these low risks of detection and relatively small sanctions under the federal FMLA, I can evaluate variation in legal risks across states to begin to address the question of deterrence. Employers in the 15 states with their own family leave laws presumably face a higher risk of detection and sanctions because they are subject to two laws and two enforcement agencies (U.S. Department of Labor 1993). Accordingly, Hypothesis 13 states that establishments in states with state family leave laws will be less likely to violate the FMLA.

It is routinely argued that corporate crime is more likely when organizations are struggling to meet performance expectations (Reference Shover, Routhe and TonryShover & Routhe 2005; Reference VaughanVaughan 1999). For example, Reference Clinard and YeagerClinard and Yeager (1980:129) report that “firms in depressed industries as well as relatively poorly performing firms in all industries tend to violate the law to greater degrees.” Recent research on trucking firms—a highly competitive industry with tight profit margins and many small organizations—finds less proactive response to environmental regulations and fewer actions that go “beyond compliance” than in other industries with a smaller set of established firms (Reference Thornton and KaganThornton, Kagan, et al. 2009). Although the evidence that financial strain prompts organizational noncompliance is decidedly mixed (Reference Geis, Salinger and BambergerGeis & Salinger 1998; Reference SimpsonSimpson 1986, Reference Simpson1987; Reference VaughanVaughan 1999), it is plausible that organizations in less profitable industries will be more likely to be noncompliant (Hypothesis 14).

Data Methods

The Survey

I analyzed a 1997 phone survey of 389 U.S. work establishments with 50 or more employees. The survey was developed by researcher Frank Dobbin and me and conducted by the University of Maryland's Survey Research Center. A stratified random sample of establishments was drawn from the Dun and Bradstreet Market Identifier database (see Reference KellyKelly 2003 for more detail). The response rate for the survey was 56 percent, and the cooperation rate (calculated as the percentage of contacted managers who completed interviews) was 74 percent. Respondents did not differ from nonrespondents in terms of establishment size, firm size, region, type of establishment (independent location, headquarters, or branch), subsidiary status, or sex of the top executive. Government agencies, nonprofit organizations, chemical manufacturers, and automobile manufacturers were significantly more likely to respond than organizations in other industries. I interpreted these findings in line with Reference Tomaskovic-DeveyTomaskovic-Devey et al.'s (1994) claim that organizations in the public sector and other firms highly regulated by the government (here, heavy manufacturers) are more responsive to the public's request for information. Organizations in the public and nonprofit sectors and larger organizations were oversampled to facilitate comparisons across sectors and size categories, so I report analyses of the weighted data. The weights are based on the Dun and Bradstreet Market Identifiers database, and they reflect the inverse of the probability that establishments were sampled.

Survey Measures of Noncompliance

The clear legal requirements of the FMLA made it possible to identify and analyze apparently noncompliant leave policies and practices as of 1997. Respondents were first asked whether there was a written policy for “leaves for new mothers” and “leaves for new fathers” and, if not, what would happen if a worker needed each type of leave. The law does not require written leave policies; it only requires that employers allow leaves in the specified circumstances. Respondents that did not have a written leave policy were asked whether workers would be allowed to take a leave, could use vacation time only, or whether decisions were made on a case-by-case basis. The first response was counted as compliance, whereas responses that workers would be allowed to take vacation time only or that decisions were made on a case-by-case basis were coded as noncompliance.Footnote 5 All three responses were read to managers who reported that they did not have a leave policy, in order to make all three responses seem acceptable. The survey then asked all respondents how many weeks of leave a new mother and a new father could take (in separate questions). These questions allowed me to analyze different forms of noncompliance, comparing organizations that provided illegally short leaves with those that did not allow any leave.

The survey measures identified significant violations of the FMLA requirements, but they did not capture all forms of noncompliance. I analyzed only parental leaves because the survey did not ask about the length of leaves to care for ill relatives or medical leaves. In addition, my measures of noncompliance with the parental leave provisions of this law ignored seemingly minor, but often consequential, violations such as the failure to post a notice about FMLA rights, the failure to continue health insurance during a leave, or penalizing workers who take family leaves (Reference AlbistonAlbiston 2005). Therefore this study provides a conservative estimate of noncompliance with the FMLA in 1997.

As with all self-reports of regulated actions, there may have been response bias at the level of participation in the study and in the truthfulness of managers' answers to the survey questions. To minimize these biases, the recruitment materials presented the survey as a broad investigation of human resources policies and practices (with no mention of the FMLA in the invitation letter), the interviewers presented a lack of leave as an acceptable action, the question about the length of leave did not prompt managers with the 12-week requirement, and the study was not associated with the enforcing agency. These strategies led me to believe that these survey questions were an improvement over previous measures of employers' noncompliance with the FMLA. Furthermore, these self-reports were better than much of the data routinely used in noncompliance research. I did not rely on complaints or target firms that have been accused of being noncompliant (e.g., Reference AlbistonAlbiston 2005; Reference Clinard and YeagerClinard & Yeager 1980; Reference Harlan and RobertsHarlan & Roberts 1998), nor did I substitute managerial intentions or motivations for data on organizational behavior (e.g., Reference MayMay 2004; Reference Simpson and PiqueroSimpson & Piquero 2002).

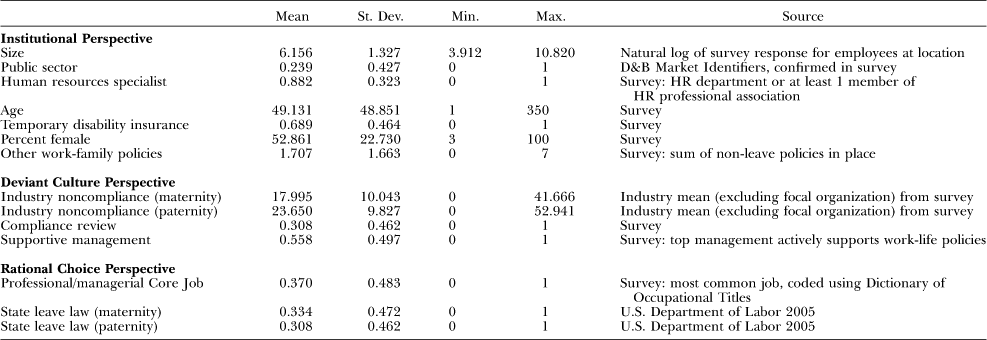

Measures of Independent Variables

Table 2 provides descriptive statistics for the variables used in the analysis and describes the data source for each variable. Two variables require further comment. First, the survey asked whether top management “actively supports work-family policies, accepts work-family policies but does not actively support them, or opposes some work-family policies.” I compared organizations in which top management was reported to “actively support” work-family policies to all others. Second, the survey asked whether the organization had ever been through a compliance review—an audit of anti-discrimination and affirmative action practices—by the OFCCP. This agency targets government contractors, but 35 percent of the establishments that did not have a federal contract as of 1997 reported having been through a compliance review.

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics

Financial performance data were limited for private sector organizations and not available for the public sector organizations in the sample. The Dun & Bradstreet database provided spotty data on the sales reported by private sector organizations, and it was not clear which year those figures referred to. For these reasons, I used industry-level data from the National Income and Products Accounts from the U.S. Department of Commerce for the 296 private sector organizations. In the private sector analyses discussed below, I average the profits before taxes for the years 1993–1997 (i.e., the period when the organizations were subject to the FMLA).

Analytic Strategy

Because I conceptualized noncompliance as a categorical variable, I estimated multinomial logit models for maternity leave and paternity leave requirements. These models summarized how a variety of organizational traits and environmental conditions are associated with the likelihood that an organization has no leave (relative to a compliant leave) and the likelihood that an organization provides illegally short leaves (relative to a compliant leave). I also estimated a second set of models to examine the predictors of having no leave as compared to having an illegally short leave. Multinomial logit models were preferable to a series of binomial logistic models (i.e., no leave vs. compliant, short leave vs. compliant) that would be based on different samples (Reference Long and FreeseLong & Freese 2003:190). Models were estimated in Stata with robust standard errors that provided correct standard errors even if model assumptions were violated, using weighted data.

The Interviews

This study also utilized 40 semi-structured interviews with the managers who were charged with developing and/or implementing human resources policies such as family leaves. Along with researcher Alexandra Kalev, I conducted the interviews in 2000 and 2001 in organizations randomly sampled from the Dun & Bradstreet Market Identifiers database. We sampled organizations in northern California, Minnesota, New York, and New Jersey and conducted in-person interviews averaging 90 minutes. The participating establishments varied greatly in size, with nine organizations employing fewer than 100 workers, 12 organizations employing between 100 and 1,000 workers, and 20 organizations employing more than 1,000 workers worldwide. We completed interviews in 46 percent of the organizations we contacted and found no significant response bias (Reference Kelly and KalevKelly & Kalev 2006). The invitation letter described the study as an effort to understand “what companies are doing (formally or informally) to help workers with their family responsibilities.” Although neither family leaves nor the FMLA were mentioned, individuals may have refused the interviews if they knew their organization was not complying with the FMLA or if they believed their organization was particularly unsupportive of workers' family responsibilities.

We asked respondents to tell us about their family leaves and then, through a series of probes, we determined when the policy had been adopted, how much time was allowed for each kind of family leave, whether and how much of it was paid, how workers learned about these leaves, whether managers had any discretion in granting leaves, and whether there had been disputes or “interesting situations” with these leaves. We also asked how many workers had taken a leave in the previous year, but less than half of our respondents could provide actual numbers or close estimates. We did not mention the FMLA by name or refer to leave laws in general until the respondents had either brought up the law or had finished describing their leave policies and practices. If time permitted, we explained that the survey had found that about a quarter of organizations were not complying with the FMLA and asked the respondent, “What is your sense of why that might be?” This question allowed us to hear more about the respondents' understanding of why noncompliance occurs without putting them on the defensive about their organization's policies.

Interviews were taped, fully transcribed, read repeatedly to identify themes and key concepts, and coded in a qualitative software program. For this article, the primary analysis was a systematic review to summarize each organization's maternity and paternity leave policies, spontaneous mentions of the FMLA (particularly the first mention), the sources of paid leave in that organization, whether and how disability insurance benefits were integrated with FMLA leaves, differences in the administration of maternity and paternity leaves, and respondents' responses to the question about why noncompliance occurs.

Findings

The Prevalence of Noncompliance

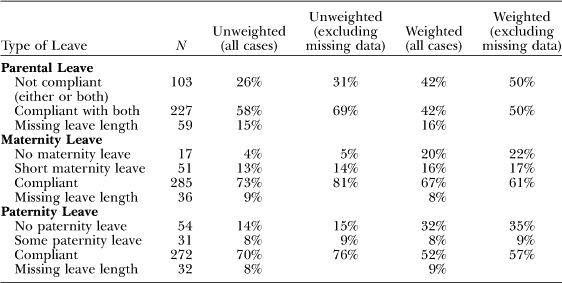

Noncompliance with the parental leave provisions of FMLA was quite common four years after the law went into effect. Even assuming that all organizations with incomplete information were actually compliant, one-quarter of the sample did not meet the basic requirements for parental leaves required by the FMLA. Furthermore, this sample overrepresented the public sector and large organizations; when the data were weighted, I estimated that up to one-half of covered establishments were not complying with the FMLA's parental leave provisions in 1997. Although the compliance rate was fairly similar for maternity and paternity leave (73 and 70 percent, respectively), Table 3 shows that organizations were more likely to provide illegally short maternity leaves than to lack maternity leave completely, and the pattern was reversed for paternity leaves.

Table 3. Noncompliance With the Parental Leave Requirements of the Family & Medical Leave Act (N=389 covered establishments)

Findings From the Survey Data

The multinomial logistic regression findings in Table 4 clearly demonstrate the utility of conceptualizing and analyzing distinct types of noncompliance rather than relying on a dichotomous analysis of compliant versus noncompliant organizations. The significance and even the signs of coefficients reveal that organizations without leaves were distinguished from compliant organizations in different ways than organizations with illegally short leaves are. The multinomial models also show that illegally short maternity leaves were better explained by the institutional perspective, while deviant culture and rational choice perspectives help explain outright noncompliance, as evidenced by a lack of leaves.

Table 4. Multinomial Logit Models of Noncompliance, Compliant Leave as Base Category

Maternity Leaves

The first column of Model 1 summarizes how the variables in the model affected the likelihood that an organization would lack maternity leave altogether, as opposed to having compliant maternity leave policies. All three perspectives received some support. Larger establishments were significantly less likely to lack maternity leave entirely than to have a compliant leave policy, as suggested in Hypothesis 1. With all other variables at their means, the predicted probability of having no maternity leave was 0.05 for the smallest organizations and less than 0.001 for the largest.Footnote 6 In support of Hypothesis 2, public sector organizations were significantly less likely to lack maternity leave policies than to have compliant leave policies.

There was also evidence supporting deviant culture and rational choice perspectives. Organizations that had been audited for compliance with antidiscrimination laws had a higher likelihood of having no maternity leave, as proposed in Hypothesis 9. Having top management that was perceived to support work-family policies significantly reduced the likelihood that an organization lacked maternity leave altogether (Hypothesis 10). Model 1 shows that organizations in states with their own maternity leave law—those subject to two different leave laws—were significantly less likely to lack maternity leave, as expected in Hypothesis 13. In models limited to the private sector (available upon request), establishments in more profitable industries were significantly less likely to lack maternity leave altogether than to have compliant policies, as suggested by Hypothesis 14.

The second column of Model 1 summarizes how the independent variables affected the likelihood that organizations had illegally short maternity leaves. The findings strongly support the institutional perspective. Human resources professionals are charged with monitoring the legal environment and updating policies as needed. As stated in Hypothesis 3, establishments with a human resources professional on site were significantly less likely to have short maternity leaves than to have compliant leaves. The predicted probability of illegally short maternity leave was 0.08 for establishments with a human resources professional and 0.26 for those without, with all other variables at their means. Having institutionalized policies that linked maternity leave to disability benefits significantly increased the likelihood that an organization would have illegally short maternity leaves rather than compliant leaves (supporting Hypothesis 4). With all other variables at their mean, the predicted probability of having short maternity leaves was 0.15 for organizations with temporary disability insurance and 0.04 for organizations without that policy in place. Forty-two of the 51 organizations (72 percent) with illegally short maternity leave reported leaves of six to eight weeks—the norm set by the disability framework. These findings clearly support the idea that some forms of noncompliance occur because of a failure to update existing policies.

Changing the base category in the multinomial logit models allowed me to investigate whether there were statistically significant contrasts between organizations with short maternity leaves and those without any maternity leaves (see notes in Table 4 and AppendixTable A1). Organizations with supportive top management were significantly more likely to end up with short maternity leave, rather than no maternity leave. Top management “values” apparently reduced the likelihood of the more extreme violations of the FMLA, but they did not affect whether or not organizations provided maternity leaves of the proper length. In addition, organizations in the public sector were much more likely to end up with short maternity leave, rather than no maternity leave. Government agencies may take care to provide some maternity leave, but they were not statistically more likely to provide enough leave time to meet the FMLA requirements.

Paternity Leaves

The first column of Model 2 in Table 4 reveals that organizations that were smaller, located in the private sector, had a compliance review, and had less supportive top management were significantly more likely to lack paternity leave altogether. The same hypotheses (1, 2, 9, 10) were supported here as in the model for the absence of maternity leaves, suggesting that the conditions that foster an outright lack of leave are similar for maternity and paternity leaves. However, the predicted probabilities of lacking maternity leave were small—even when an organization had the significant “risk factors”—while the predicted probabilities for lacking paternity leave were considerably larger. The predicted probability of lacking paternity leave was 0.03 for organizations with supportive top management and 0.13 for organizations with less supportive leaders, with all other variables at their mean. The predicted probability of lacking paternity leave was 0.15 for organizations that had been through a compliance review and 0.03 for other organizations. Public sector organizations were much less likely than private sector organizations to lack paternity leave (predicted probabilities of 0.02 and 0.08, respectively), but government agencies were actually more likely than private sector organizations to have illegally short leaves (predicted probabilities of 0.09 and 0.03). Models using a dichotomous measure of compliance did not reveal these distinctions and did not produce a significant coefficient for public sector organizations. In models limited to the private sector (available upon request), industry profitability significantly reduced the likelihood that an organization would have illegally short paternity leaves, as compared to compliant paternity leave. This partially supports Hypothesis 14.

I proposed that noncompliant paternity leaves would be more likely in organizational settings where traditional gender norms about men's limited involvement in caregiving were stronger. There was no support for Hypothesis 6 suggesting that the percentage of male employees would affect paternity leave noncompliance.Footnote 7 In models not reported here, I explored whether workplaces where men were in a strong majority (more than 66 percent male and more than 80 percent male) were more or less likely to have noncompliant paternity leaves; these predictors were not significant either. As expected in Hypothesis 7, organizations with other (gender-neutral) work-family policies in place were more likely to have paternity leaves in place as well. Each additional work-family policy reduced the likelihood that an organization would lack paternity leave completely.

As seen in the second column of Model 2, there were no statistically significant coefficients for illegally short paternity leaves. In other words, none of the variables in the model predicted whether an organization would provide illegally short paternity leaves rather than compliant leaves. The one variable that was marginally significant (p=0.07) in this model was a human resources specialist (consistent with Hypothesis 3). Workplaces with a local human resources specialist had a predicted probability of illegally short paternity leaves of 0.03, as compared to 0.13 for establishments without a professional on site. This points again to the role of human resources specialists in paying attention to the details of the FMLA.

The model suggests that organizations with illegally short paternity leaves are not bad apples; indeed, they seem to be the same as compliant organizations. Common models that utilize a dichotomous measure of compliance/noncompliance would miss this information by lumping together organizations with no leaves and organizations with illegally short leaves. These analyses show that it is only organizations with no paternity leave that can be distinguished from compliant organizations. The interview data below reveal that these similarities are due to the continued power of a traditionalist gender regime in both officially compliant organizations and those with illegally short paternity leaves.

Findings From the Interviews

The interviews strongly supported an institutional perspective on the compliance process. The accounts provided by the managers substantiated the key findings from the maternity leave models about the conditions fostering attentiveness to the law and the continued influence of the older disability framework in the administration of maternity leaves. Respondents in smaller organizations and especially those in establishments with fewer or less professionalized human resources staff described the challenges of keeping up with the law. The interviews also helped make sense of the nonsignificant contrasts in the paternity leave models because they revealed the strong influence of institutionalized norms about men's caregiving in compliant and noncompliant organizations alike. Management practices reinforce institutionalized gender norms and discourage long paternity leaves, regardless of whether official policy provides 12 weeks or less.

It is possible that overt resistance to the FMLA is also a strong motive for noncompliance, even though such resistance was very rarely expressed in the interviews. Managers who had deliberately decided not to comply with this law may have chosen not to participate in the interview study as well. Furthermore, participating managers may not have discussed their strategic resistance to this law because of social desirability bias. The concept of “normalization of deviance” also suggests that individuals in noncompliant organizations may reconstruct their behavior as appropriate or even lawful, in their own thought and in their discussion with others (Reference VaughanVaughan 1996, Reference Vaughan1999). While these data do not rule out resistance to the law as a motive for noncompliance, the perspectives that were shared in the interviews point to the need to integrate an institutional perspective into the study of noncompliance.

Institutionalized Policies and Questionable Compliance for Maternity Leave

The interviews supported the claim that noncompliance with maternity leave often happens because older leave policies have not been updated to match the requirements of the FMLA. Managers in the seven organizations with questionable maternity leave policies described these leaves using the disability framework rather than the FMLA. These organizations may allow up to 12 weeks of leave for mothers if women push for it, but they focused first and foremost on the shorter, paid disability leaves. For example, when asked whether the company had a policy allowing women to take leave when a child is born, the manager in a small manufacturing organization answered simply, “No.” The interviewer followed up with this question: “What happens when a worker is pregnant?” and the manager responded, “When a worker is pregnant, it's handled like a normal disability” and continued on to say that the leave length “all depends on what the doctor says … . Because having a baby, by law, isn't anything different than breaking a leg.” This was an accurate description of the law regulating maternity leave as of 1992, but it did not reflect the requirements of the FMLA. A manager at a large manufacturing company responded to the question “How many weeks of leave does the new mother get?” by saying “Normally six.” The interviewer later tried to probe to clarify how long maternity leaves could be, including both paid and unpaid leave time, and the manager responded:

In general, a mother who is having a child is usually allowed six weeks, and they're under the doctor's care for that amount of time. If it turns out that they have to be under the doctor's care longer than that, then it would be whatever it is. But, in general it's six weeks (emphasis added).

Employees in this organization may or may not hear about their rights to unpaid leave because the disability framework and pregnancy discrimination laws still dominate these managers' understanding of what maternity leave is.

The presence of disability policies does not necessarily lead to leave violations of the FMLA. Sixteen organizations provided disability insurance benefits for the first six to eight weeks of a maternity leave but also made it clear that employees could take a total of 12 weeks of leave. In a textbook example of how the disability benefits and the FMLA requirements should interact, the manager from a mid-sized advertising agency explained:

Under our policy, if they've been here one year, obviously they're eligible for FMLA. They can have up to 12 weeks off, unpaid. And if they return within the 12 weeks, they return to the same paying position, etc. What we have that runs, additionally, is our short-term disability [insurance] that compensates an employee that's out for medical leave and it compensates them at 100 percent for up to 12 weeks, depending on what the physician recommends for sufficient time off. Generally, we've seen that it's been six weeks. So they'll get six weeks of full pay, and then what they do is the last six weeks (because most of them now take 12), they'll use personal time, some vacation, a mixture.

Organizations can combine older and newer leave policies in compliant and even generous ways that go “beyond compliance.” Eleven organizations had policies that allowed mothers to take disability leave and then begin their FMLA time, so that they would end up with up to 18 weeks of leave.

Limited Administrative Capacities Encourage Noncompliance

Respondents routinely explained other firms' noncompliance by pointing to their own or others' confusion about the law. Respondents also expected that confusion and the noncompliance associated with it were more likely to occur in smaller organizations and those that had limited human resources staff (as the survey analysis showed). For example, a manager for a county government in California responded to the question about why she thought other organizations did not comply with the FMLA by saying:

So one thing is nobody understands it. Smaller private employers and even smaller public employers are mystified by some of these laws. They don't quite know how to ask, “What does this mean?” They get very upset and all these changes are often beyond the capacity of smaller organizations to implement. Now that's not an excuse, but it's real. They may have an overworked HR department of one person, who now in addition to everything else that person is doing has to figure out how to get this information out, work with the payroll department, work with the supervisors, develop the policy for implementing, get a form ready. It's a lot of work.

Other respondents conveyed that financial capacity to do what the law requires was not the issue; instead, noncompliance was related to administrative capacity to know what the law requires. The human resources manager at a transportation company with about 200 employees pointed to the limited familiarity with the law among some human resources staff. She explained:

I don't think it's that people don't want to comply. I think that it's just very difficult to stay on top of it. I sat in that class at the [local university's business school] … . There were probably 50 or 60 people in that class with me. Over half, which surprised me, knew less about it than I did. There were even some people that didn't have any idea of what the law was. They're just people in companies [pause]. Oftentimes I think you see administrative assistants (like I used to be) put into an HR role, I think that happens more and more, and you just don't know [about the law].

Although this organization seemed to be compliant with the FMLA, the ellipses above mark the place where she commented: “I think that we do a darn good job, although I've made mistakes. We tried to fix them or correct them as soon as we realize what we've done, but it's never intentional to not comply.” The administrative capacity explanation dominated respondents' discussion of why noncompliance occurs, with only three respondents presenting other explanations.

Institutionalized Gender Norms and Noncompliant Paternity Leaves

Institutionalized expectations that men are not, and perhaps should not be, caregivers drove some noncompliance with the FMLA's paternity leave requirements. A respondent from a small, high-tech company revealed noncompliant paternity leaves, ignorance about the law's coverage of men, and the most explicit statement of disapproval about men's use of leaves in these interviews. After a discussion of maternity leaves, he was asked:

Interviewer: Do you offer anything to new fathers? What happens?

Respondent: Not anything formally.

Interviewer: And what do you have informally?

Respondent: I don't think we've run into it. Or we haven't run into it where the father wanted any extensive time off. That would have created a problem here because each position that we have here, we don't have a way to cover for someone else … if they wanted like three months off to be with their newborn child that would be a major economic problem for us. And we probably wouldn't be able to support that.

Interviewer: So were there cases in which new fathers asked for a week?

Respondent: I haven't ever had any. I don't remember any employees that have been here having babies. They may have, but it never came up to my attention with respect to time off or I don't remember ever getting a cigar from anybody.

Although the manager did not appear to know that the FMLA covers fathers, he responded to the question about leaves to care for seriously ill relatives by saying, “I think that comes from the Family Leave Act. And that if it's a direct relative, there are requirements that the company needs to support that.” Later, the manager was asked:

Interviewer: What do you think about family leave?

Respondent: I'm not sure if lots of it is needed. I think that there are many situations where [pause]. I don't think the husband needs a leave for having children. I don't know where that came from and I'm not a really strong supporter for that. I am a strong supporter for the woman or if something biological happens (emphasis added).

A second example illustrates that organizations may simultaneously do more than the law requires by providing paid paternity leave but not comply with the FMLA requirements on leave length. These short leaves—even when they are paid—reinforce the expectation that men are not primary caregivers. A manager at a large advertising agency first said no when asked if the firm had paternity leave. The current practice at this company was simply for the father to take two or three days off. The manager explained, “So, we sort of say, ‘Please, be with your family. You need to be with your family now,’ knowing that we'll get that time back from them one way or another.” She later explained that the company was planning to initiate three days of paid paternity leave and revealed her expectation that fathers have a subordinate, supportive caregiving role:

What we did was we surveyed the advertising industry of what the other competitors offered. And it was an average of three to five days [of paid paternity leave]. And most of the agencies were doing three. And we felt that three was suitable. For two reasons: Now a female is in the hospital an average of 24 to 48 hours following the delivery of a child. So we felt that three days was more than enough time to take care of the remaining siblings at home, if necessary, while the mom was in the hospital. And one or two more days to be at home with the mom and the new baby, to help her, and certainly be able to go one or two days to the hospital to see her. So, we felt that three days was suitable (emphasis added).

This respondent knew about the FMLA. She noted that there was no discretion with maternity leave “because maternity is protected by the Family Medical Leave Act, so they're entitled to take that.” But the manager apparently did not believe the FMLA applied to fathers. When asked, “What about paternity leave? Do managers have latitude?” she said:

They do, because again it's not a formalized policy. So if there's a male employee that says, “I want to take three days off,”the manager can say no, if they're in the middle of something. I'm not aware of that ever happening here though (emphasis added).

Although the respondent claimed that supervisors would normally allow these short paternity leaves, men in this organization have not achieved the right to leave that was intended in the FMLA.

Institutionalized Gender Norms and Paternity Leave Practices in Compliant Organizations

Institutionalized gender norms influenced management practices and the leave time men actually took in compliant, as well as noncompliant, organizations. Respondents in compliant organizations reported that men generally took short leaves, often using vacation time or personal days rather than official FMLA or paternity leave. About one-third of the respondents said that they did not know of a single case of a father taking significant time off, and the remaining two-thirds said that fewer than five men had done so.Footnote 8 Compliant policies are clearly not sufficient to increase men's use of leaves. Employees must also know about their rights and choose to claim them (Reference AlbistonAlbiston 2005; Reference Baird and ReynoldsBaird & Reynolds 2004; Reference SchusterSchuster et al. 2008). Men's limited use of family leaves is certainly influenced by their (socially constructed) preferences and identities and the lack of income replacement in FMLA leaves. But there are also specific management actions that discourage men from mobilizing their rights.

Managers may question men's use of leaves even in compliant organizations and thereby reinforce institutionalized, gendered patterns of caregiving. When the human resources manager of a state agency was asked whether men took family leave, he said they definitely did to care for family members. “If the wife has had a baby and has some problems,” a man can take family leave, he reported. The interviewer said: “I know this isn't common, but what would happen if a man wanted to take 12 weeks of family leave to take care of the infant?” The manager replied that a man in that situation could take a leave, because it was covered by the FMLA and a state parental leave law. But the respondent also said that he would investigate to “be sure the man was sincere” and didn't just “want 12 weeks off.” He also noted that the father's supervisor would probably try to get the man to work part-time during this time, because “of operational needs.” Despite operational needs, the same respondent reported that most women took six months of leave after a birth. Organizations like this one may comply with the FMLA's paternity leave provisions when push comes to shove, but men will be less likely to push for leaves in these settings.

Managers and coworkers may be critical of fathers who use leaves. A human resources manager for a city reflected on the likely response to a city employee taking paternity leave:

The concern here might be that they might be viewed as not fitting in. I'm thinking of the police department, for instance. If they wanted to go out for a couple of months and stay home with the family. Uh [comic pause], no. That wouldn't fit the mold of the law enforcement environment … . And I'm wondering if that still might be a little too revolutionary for some.

A mid-sized transportation company did more than the law required by providing a six-month leave policy to women and men. However, women received paid family leave (after the disability period) and men's paid leave was limited their accrued vacation. When I asked the respondent whether she knew why men were not covered, she answered:

This is confidential, right? I can tell you that a lot of the people that are in management here have been here a long time, from the old school. [These managers believe:] You don't pay dads to take time off to be home to take care of the children. Just forget it, that's ridiculous. I never did it. Forget it. My wife takes care of that stuff.

Perhaps feeling uncomfortable for having criticized her superiors in this way, she immediately commented:

And I think it would be a lot of inconvenience. There was a warehouse manager that was one of the guys that took the leave. He took a six-month leave and there was a tremendous hardship for the warehouse … . His wife stayed home six months and then he stayed home six months. They wanted a year with their baby at home without daycare. Then when he did come back, he took a second shift position so they worked opposite shifts so they had another whole chunk of time. I thought that was a really neat way to do it. It was interesting how people didn't. Some of them—men especially—in the organization just thought that was ridiculous that he would go that far.

The manager reported that most men in the company took “maybe the day of the birth, maybe the few hours at the hospital. ‘I'll be right there, honey, when I finish this phone call.’ The baby's born, back to work with cigars.” These findings illustrate how institutionalized gender norms continue to influence everyday practices even in organization with compliant or generous official policies.

Conclusion

Employment laws such as the FMLA challenge the ways things have been done and lay out what organizations should do. This kind of mandate is institutional pressure for organizational change in perhaps its purest and most overt form. But existing institutions—in this case, institutionalized disability policies that provide some paid maternity leave and institutionalized norms about men's role in families—influence how organizations act (or do not act) in response to the changing legal environment. Noncompliance sometimes occurs through a failure to update previously institutionalized policies and practices to bring them into line with current law.

This point has not been theorized in previous research on noncompliance. Indeed, most research on noncompliance uses dichotomies, contrasting legal with illegal behavior, rather than considering the possibility that there are different forms of noncompliance that reflect different processes and are found in different contexts. This article provides evidence about which organizations are more likely to violate the FMLA in different ways. Both survey and interview evidence point to information overload—particularly in smaller organizations and those with less professionalized human resources staff—as a cause of noncompliant maternity leaves. Noncompliance is also more likely when organizational actors who are ambivalent about the legal changes (such as men's right to longer family leaves) conveniently forget to check whether their policies and practices need to be updated. In both situations, there does not seem be a calculated decision to violate the law, but the end result is that employees are not availed of the family leaves promised in the FMLA.

This work has several implications beyond the case of FMLA noncompliance. First, the finding that different forms of organizational noncompliance have different causes parallels the move within criminology to identify different offender trajectories (e.g., Reference Moffitt and CullenMoffitt's [2008] adolescent-limited and life-course persistent offenders) and specify the predictors of these different patterns (e.g., Reference ChungChung et al. 2002). Identifying different forms or patterns of offending has implications for enforcement policies and strategies; I discuss this below. Second, noncompliance from a failure to update existing policies and practices is likely to occur in other legal domains, although additional research is needed. This type of analysis might proceed by categorizing continuous data, such as emissions released by a polluting organization, into levels such as “very high,”“levels near the requirements of an older law,”“levels at or near the current legal requirements,” and “levels lower than the current law requires.” Scholars studying health and safety regulations might be able to separate noncompliance into categories such as “no ergonomic adjustments,”“equipment that is responsive to older regulations,” and “equipment that complies with current regulations.”

When is noncompliance from a failure to update most likely to occur? I suggest three conditions that encourage this form of organizational noncompliance. First, this may be more likely when laws or regulations require affected parties to file complaints or lawsuits to start an investigation, rather than having an agency that inspects or audits organizational compliance. Regulators routinely educate the regulated parties about their (new) obligations under the law during inspections or audits (Reference Gray and ShadbegianGray & Shadbegian 2005; Reference Thornton and GunninghamThornton, Gunningham, et al. 2005). Second, this type of noncompliance and, more generally, confusion about legal requirements may be more likely to occur when an organizational action is regulated by both state and federal laws or by multiple federal laws. For example, in my interviews, even well-informed managers reported confusion about how to reconcile the medical leave requirements of the FMLA with the Americans with Disabilities Act (1990)—two related laws that are enforced by separate federal agencies. Third, and most broadly, this form of noncompliance may be more likely in welfare states that provide less of the social safety net through public programs and instead deliver key benefits through employers. As Reference GottschalkGottschalk (2000:1) notes in her description of the “shadow welfare state” in the United States, “The United States has quite an extensive but generally overlooked welfare state that is anchored in the private sector but backed by government policy.” In the realm of family-supportive policies, we ask employers to do more—pay less in taxes, but do more administratively—than many other industrialized nations (Reference Kelly and Pitt-CatsouphesKelly 2005). When organizations do not comply with these laws, employees miss out on the rights and benefits promised to them by the state.

If previously institutionalized policies, practices, and norms encourage noncompliance, what might destabilize the older institutions and bring about more social change? First, I suggest that additional education about the FMLA may reduce noncompliance and increase utilization of parental leaves (at least modestly). Because some forms of noncompliance may be unintentional, it would be useful to educate employers about the FMLA and how the disability policies related to the Pregnancy Discrimination Act (1978) should mesh with the FMLA. Because smaller establishments and those without human resources professionals may not attend training on the FMLA, a public education campaign is an important complement to programs for employers. Furthermore, employees who are familiar with the FMLA may educate their employers, mobilize their rights by requesting leaves, and dispute decisions that are arguably noncompliant. It is often difficult and frightening to mobilize rights within the workplace (Reference AlbistonAlbiston 2005; Reference Budd and BreyBudd & Brey 2003; Reference McCannMcCann 1994; Reference Nelson and BridgesNelson & Bridges 1999), but public education campaigns may make this process less intimidating. Second, a federal law creating paid parental leaves could render older policies and practices irrelevant and thereby reduce noncompliance. However, public education is needed for full utilization even when paid leave is available. A recent study shows limited awareness of California's Family Leave Insurance program (which provides some pay during family leaves) even among parents who were especially likely to need leave because they had a child with a serious health condition (Reference SchusterSchuster et al. 2008). Even if a federal paid leave law is not passed anytime soon, campaigns for paid leave—and the debate that would surely ensue—may increase both workers' and managers' awareness of existing rights under the FMLA and perhaps reduce some forms of noncompliance with the existing law.

Appendix

Table A1. Multinomial Logit Model of Regression, With Illegally Short Leaves as Base Category

Notes:

+ p<.10,

* p<.05,

** p<.01.