Coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) is an acute respiratory syndrome that emerged in the Chinese city of Wuhan in December 2019, then rapidly spread weeks later to reach other countries of the world to become a global threat. The WHO(1), as a result, declared Covid-19 to be a pandemic in March 2020. As of December 2021, there were over 279 million confirmed cases and over 5 million and three hundred and ninety thousand deaths(2). Due to the increasing numbers of cases worldwide, health authorities undertook strict measures to control the virus’s further spread, including social distancing, curfew, quarantines, closure of non-essential businesses and complete lockdowns(Reference Kraemer, Yang and Gutierrez3). These measures, albeit necessary, were associated with negative concomitants as they led to the drastic rise in unemployment rates(4) and to adverse modifications in the populations’ lifestyles(Reference Butler and Barrientos5–Reference Barkley, Lepp and Glickman8). The lockdowns negatively impacted the dietary practices of individuals manifested in the elevated consumption rate of foods high in sugars, refined carbohydrates and saturated fats(Reference Butler and Barrientos5,Reference Bennett, Young and Butler6) . The lockdowns also limited physical activity due to the closure of many fitness and recreational centers(Reference López-Moreno, López and Miguel7,Reference Barkley, Lepp and Glickman8) . In return, these deleterious lifestyle changes rendered the world more susceptible to obesity(Reference Lin, Vittinghoff and Olgin9) and various chronic diseases(Reference Lippi, Henry and Sanchis-Gomar10,Reference Chandrasekaran and Ganesan11) .

College students were among the populations most vulnerable to the lockdowns due to the unprecedented modifications they had to acclimate to. The closure of campuses, suspension of standard in-person learning, transition to fully online instruction(Reference Fawaz, Al Nakhal and Itani12–Reference Khawar, Abbasi and Hussain15), attenuation of social interaction(Reference Wathelet, Duhem and Vaiva16–Reference Hakami, Khanagar and Vishwanathaiah22), financial challenges(Reference Lee, Jeong and Kim23,Reference Sahile, Ababu and Alemayehu24) and the uncertainty of the future have dramatically disrupted their psychosocial functioning(Reference Elmer, Mepham and Stadtfeld25) and altered their lifestyles(Reference Sahu26). Even preceding the pandemic, college students were highly vulnerable to inadequate diet and physical activity(Reference Kang, Ciecierski and Malin27–Reference Perusse-Lachance, Tremblay and Drapeau29). Studies in the USA(Reference Kang, Ciecierski and Malin27) and Canada(Reference Busque, Yao and Miquelon28,Reference Perusse-Lachance, Tremblay and Drapeau29) , for example, have shown that, even prior to the pandemic, college students were not meeting the recommended intake for daily servings of fruits and vegetables. The pandemic unfavourably modified the college students’ lifestyles further and thus rendered them more susceptible to weight gain especially during the lockdown periods(Reference Millán-Jiménez, Herrera-Limones and López-Escamilla30–Reference Tavolacci, Ladner and Déchelotte35). Additionally, research suggests that college students were at high risk of becoming food insecure during the pandemic due to factors such as loss of employment, ineligibility to governmental economic relief efforts and alterations in living arrangements and housing status(Reference Silva, Osborn and Owens36–Reference Soldavini, Andrew and Berner43).

The detrimental impact of the pandemic on the physical activity level among college students has been researched, and the major study findings were weighed and presented in a review by López-Valenciano et al.(Reference López-Valenciano, Suárez-Iglesias and Sanchez-Lastra44). However, not much recent work has been done to assess the overall findings of studies investigating the association between the pandemic and the diet, body weight and food security status of college students. Thus, we conducted a systematic review to consolidate evidence for the effect of COVID-19 on college students’ dietary quality, dietary habits, body weight and food security status.

Methods

Search strategy and inclusion criteria

The search was conducted based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)(45). To identify relevant studies, a comprehensive electronic search was conducted in Google Scholar, MEDLINE, ScienceDirect, Embase and Scopus. The reference lists of the identified investigations were also used to extract articles. The search was restricted from March 2020, which marks the start of the lockdown, to September 2021. The following key terms were searched: (1) ((‘weight’ OR ‘weight gain’) AND (‘students’ OR ‘college students’) AND (‘pandemic’ OR ‘covid-19’ OR ‘corona virus’)); (2) ((‘diet’ OR ‘diet quality’ OR ‘dietary pattern’ OR ‘dietary habits’ OR ‘food intake’) AND (‘students’ OR ‘college students’) AND (‘pandemic’ OR ‘covid-19’ OR ‘corona virus’)); and (3) ((‘food security’ OR ‘food insecurity’) AND (‘students’ OR ‘college students’) AND (‘pandemic’ OR ‘covid-19’ OR ‘corona virus’)).

To be incorporated in this review, studies had to: (i) be published in peer-reviewed journals; (ii) be written in English; (iii) include students of higher education; (iv) measure the prevalence of obesity during the pandemic; (v) measure the prevalence of food insecurity during the pandemic; (vi) assess the changes in dietary habits and (vii) assess the changes in diet quality. We excluded investigations that did not include higher education students, did not measure the prevalence of obesity or food insecurity during the pandemic, did not assess the changes in diet quality or dietary habits and were review studies.

Screening and data extraction

Two independent reviewers, T.J. and R.K. screened the retrieved abstracts and full texts and assessed them for inclusion using EndNote X7(46). Disagreements between the two authors were resolved by discussion with the rest of the authors (R.A.H. and H.D.S.).

The electronic search identified 1529, 948 and 387 records related to the effect of the pandemic on diet quality/dietary habits (Fig. 1), body weight (Fig. 2) and food insecurity (Fig. 3), respectively. From these citations, 812, 486 and 241 duplicates were excluded, respectively. The remaining abstracts were then screened from which 429, 393 and 86, were excluded, respectively, for reasons such as conference abstracts, the lack of full texts, etc. Finally, the full-text articles were screened for eligibility based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria; articles were excluded for reasons such as published in a language other than English (13, 4 and 7 articles, respectively), did not target college students (189, 35 and 26 articles, respectively), did not provide assessment of changes in diet quality/dietary habits (38 articles), did not provide data on body weight changes (9 articles), did not provide data on prevalence of food insecurity (18 articles) and were preprints (24, 6 and 9 articles, respectively).

Fig. 1. Screening process for the review of the impact of COVID-19 on diet.

Fig. 2. Screening process for the review of the impact of COVID-19 on body weight.

Fig. 3. Screening process for the review of the impact of COVID-19 on food insecurity.

Data were extracted by two authors independently, T.J. and R.K., using Excel (version 15·37). Disagreements were discussed and resolved with the rest of the authors (R.A.H. and H.D.S.). The following data were extracted from the papers: author, year of publication, date of data collection, country, sample size, assessment tools for measuring diet quality, dietary habits, food insecurity, body weight and the key findings. The extracted results included the intake of various foods and food groups, the dietary habits such as cooking, shopping, snacking and ordering fast food, the prevalence of food insecurity, and the percentage of college students who gained weight during the pandemic.

Quality assessment and synthesis of findings

The methodological quality of all the included studies was evaluated independently by T.J. and R.K. using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for non-randomised studies(Reference Wells, Shea and O’Connell47). This scale utilises a ‘star’ system that ranges from 0 (minimum) to 9 (maximum) to assess the quality of studies in three subscales: comparability of subjects; selection of participants and the assessment of exposures/outcomes. Studies that scored seven to nine stars were deemed to be of high quality. Disagreements were discussed and resolved with the rest of the authors (R.A.H. and H.D.S.)

From the selected studies, diet-related findings were extracted and presented under two different themes, ‘Diet Quality’ and ‘Dietary Habits’. Under ‘Diet Quality’, different food groups such as ‘Fruits and Veggies’, ‘Dairy Products’, etc as well as ‘Alcohol’ were presented separately. The percentage of the study population that changed their intake of specific foods under each food group, such as ‘fruits’ under ‘Fruits and Veggies’, was discussed and displayed on a table.

When it comes to dietary habits, findings were extracted and presented under different themes including ‘Binge Eating’, ‘Breakfast Skipping and Meal Timing’, ‘Cooking’, ‘Shopping’, ‘Snacking’ and ‘Ordering Fast Food’. These were the most commonly prevalent habits among the college students during the pandemic. Under each theme, the percentage of the study population that changed their particular dietary habit was discussed textually and displayed in a table.

Findings related to the change in the prevalence of weight gain from before to during the pandemic were also extracted and presented in a table. The different factors that were associated with this weight gain were discussed under different themes. For instance, the foods and food patterns shown to have an association with weight gain during the pandemic were discussed under ‘Diet’. Factors such as reduction in physical activity and increase in screen time were discussed under ‘Lack of physical activity’.

The prevalence data of food insecurity among college students during the pandemic along with the different factors associated with it were extracted then presented textually and in a table.

Results

The findings of this systematic review were presented under three different themes: diet, body weight and food insecurity.

Diet

We found that twenty-four studies met the inclusion criteria and assessed the dietary changes of college students during the pandemic(Reference Millán-Jiménez, Herrera-Limones and López-Escamilla30–Reference Palmer, Bschaden and Stroebele-Benschop32,Reference Dragun, Veček and Marendić34–Reference Sidebottom, Ullevig and Cheever37,Reference Al-Musharaf, Aljuraiban and Bogis48–Reference Cheng and Wong64) . Most of these investigations were cross-sectional and measured the college students’ diets via online questionnaires (online supplementary table). Findings related to diet were further grouped into two different sections, dietary intake and dietary habits.

Diet quality

Overall, in studies conducted in various nations, the diet quality of college students was reduced(Reference Silva, Osborn and Owens36,Reference Jia, Liu and Xie55,Reference Kilani, Bataineh and Al-Nawayseh57,Reference Bertrand, Shaw and Ko62) during the pandemic due to the decrease in the intake of whole grains(Reference Bertrand, Shaw and Ko62), dairy products(Reference Dragun, Veček and Marendić34,Reference Boukrim, Obtel and Kasouati49,Reference Jia, Liu and Xie55,Reference Bertrand, Shaw and Ko62,Reference Cheng and Wong64) , legumes(Reference Jia, Liu and Xie55), nuts(Reference Bertrand, Shaw and Ko62), fruits and vegetables(Reference Sidebottom, Ullevig and Cheever37,Reference Jia, Liu and Xie55,Reference Bertrand, Shaw and Ko62,Reference Cheng and Wong64) and the increase in the intake of confectionery products(Reference Palmer, Bschaden and Stroebele-Benschop32,Reference Dragun, Veček and Marendić34,Reference Huber, Steffen and Schlichtiger52,Reference Cheng and Wong64) and refined grains(Reference Palmer, Bschaden and Stroebele-Benschop32,Reference Huber, Steffen and Schlichtiger52) . Nevertheless, research strongly indicates that the diet quality improved during the lockdown in the study populations in certain nations, especially Spain, which enhanced their adherence to the Mediterranean dietary pattern(Reference Celorio-Sardà, Comas-Basté and Latorre-Moratalla31,Reference Dragun, Veček and Marendić34,Reference Imaz-Aramburu, Fraile-Bermúdez and Martín-Gamboa53) .

Fruits and veggies

The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the intake of fruits and vegetables varied based on the country. Studies conducted in nations that follow the Mediterranean diet indicated an increase in the intake of fruits(Reference Celorio-Sardà, Comas-Basté and Latorre-Moratalla31,Reference Dragun, Veček and Marendić34) and vegetables(Reference Celorio-Sardà, Comas-Basté and Latorre-Moratalla31,Reference Imaz-Aramburu, Fraile-Bermúdez and Martín-Gamboa53) among college students during lockdown. Celorio-Sardà et al. (Reference Celorio-Sardà, Comas-Basté and Latorre-Moratalla31), for instance, carried out a cross-sectional study to assess the dietary changes of Food Science students in Spain and showed that 24 % and 20 % of the study population increased their fruit and vegetable intake, respectively, during the pandemic. Imaz-Aramburu et al. (Reference Imaz-Aramburu, Fraile-Bermúdez and Martín-Gamboa53), in a longitudinal study conducted to assess the lifestyle changes of Health Sciences students from before to during the pandemic in Spain, showed that the percentage of the study population consuming vegetables increased from 59·8 % to 65·8 %, respectively.

Studies conducted on populations who were not following the Mediterranean dietary pattern, such as Canada(Reference Bertrand, Shaw and Ko62), China(Reference Jia, Liu and Xie55), Malaysia(Reference Cheng and Wong64) and the USA(Reference Sidebottom, Ullevig and Cheever37), indicated that the intake of fruits and vegetables among college students was reduced during the pandemic. Jia et al. (Reference Jia, Liu and Xie55), for instance, administered the Lifestyle Change Survey (COINLICS), a nationwide retrospective survey distributed via social media platforms, on 10 082 youth participants in China, before and after the lockdown and showed that there was a significant decrease in the percentage of students consuming fresh vegetables (from 56·9 % to 55·9 %) and fruits (from 24·7 % to 24 %).

Alcohol

Emerging but limited evidence suggests that alcohol intake increased during the pandemic in certain study populations(Reference Sidebottom, Ullevig and Cheever37,Reference Brancaccio, Mennitti and Gentile50,Reference Bertrand, Shaw and Ko62) . Bertrand et al. (Reference Bertrand, Shaw and Ko62) administered an online questionnaire before and during the pandemic on 125 students from the Universities of Saskatchewan and Regina in Canada to assess alcohol intake and showed a significant increase. An escalation in alcohol intake was also observed in a college population in Southwestern USA(Reference Sidebottom, Ullevig and Cheever37) and was more pronounced among males than females(Reference Brancaccio, Mennitti and Gentile50).

Alcohol intake has been shown to decrease during the pandemic in other populations such as Spain(Reference Millán-Jiménez, Herrera-Limones and López-Escamilla30,Reference Celorio-Sardà, Comas-Basté and Latorre-Moratalla31) and Korea(Reference Kang, Yun and Lee56). Millán-Jiménez et al. (Reference Millán-Jiménez, Herrera-Limones and López-Escamilla30), for instance, administered an online survey on medicine and architecture undergraduate students at the University of Seville, Spain. The study showed that 59 % reported alcohol consumption; however, data from pre-confinement attained from a national survey conducted by the Spanish Drugs and Addictions Observatory (OEDA) showed that 72 % of the Spanish population consumed alcohol.

Dairy products

The majority of the existing studies have shown that the intake of dairy products was below recommendations during confinement(Reference Dragun, Veček and Marendić34,Reference Boukrim, Obtel and Kasouati49,Reference Jia, Liu and Xie55,Reference Bertrand, Shaw and Ko62,Reference Cheng and Wong64) . Boukrim et al. (Reference Boukrim, Obtel and Kasouati49), using a reference score of the National Nutrition and Health Program (PNNS-GS) to measure the effect of confinement on the dietary habits of students of higher education in Southern Morocco, showed that only 18·47 % of participants met the recommendations for dairy products. The majority (76·11 %) consumed dairy products less than 2·5 times a day during the confinement. Gender differences were observed(Reference Boukrim, Obtel and Kasouati49,Reference Jia, Liu and Xie55) . Jia et al. (Reference Jia, Liu and Xie55) denoted that females consumed less dairy products than males during the lockdown.

Protein foods

Research has shown that study populations adhering to the Mediterranean diet increased their fish intake during the pandemic(Reference Celorio-Sardà, Comas-Basté and Latorre-Moratalla31,Reference Dragun, Veček and Marendić34) . In a cross-sectional study carried out to assess the dietary habits of medical students in Split, Croatia, Dragun et al. (Reference Dragun, Veček and Marendić34) showed an increase in the adherence to the Mediterranean diet when it came to fish during the pandemic compared with the pre-COVID-19 period. Research conducted on other study populations indicated there was little to no effect of the pandemic on fish intake(Reference Boukrim, Obtel and Kasouati49).

The lockdown also had little to no impact on the intake of legumes(Reference Celorio-Sardà, Comas-Basté and Latorre-Moratalla31,Reference Dragun, Veček and Marendić34,Reference Imaz-Aramburu, Fraile-Bermúdez and Martín-Gamboa53,Reference Jia, Liu and Xie55) . Dragun et al. (Reference Dragun, Veček and Marendić34) denoted in their study that college students slightly increased the intake of legumes in Spain during lockdown. On the other hand, Jia et al. (Reference Jia, Liu and Xie55) indicated a decrease in the percentage of students (from 7·3 % to 6·3 %, respectively) consuming soya bean products from before to during the lockdown.

Regarding the intake of nuts(Reference Dragun, Veček and Marendić34,Reference Imaz-Aramburu, Fraile-Bermúdez and Martín-Gamboa53,Reference Bertrand, Shaw and Ko62) and meat(Reference Palmer, Bschaden and Stroebele-Benschop32,Reference Boukrim, Obtel and Kasouati49,Reference Imaz-Aramburu, Fraile-Bermúdez and Martín-Gamboa53,Reference Jia, Liu and Xie55,Reference Kang, Yun and Lee56,Reference Bertrand, Shaw and Ko62) , research findings were less consistent. Imaz-Aramburu et al. (Reference Imaz-Aramburu, Fraile-Bermúdez and Martín-Gamboa53), for instance, observed in their study population that the percentage of the study population consuming fatty meats increased from before to during the pandemic (68·8 % to 75·9 %, respectively). Bertrand et al. (Reference Bertrand, Shaw and Ko62), Palmer et al. (Reference Palmer, Bschaden and Stroebele-Benschop32), Kang et al. (Reference Kang, Yun and Lee56), and Jia et al. (Reference Jia, Liu and Xie55), on the contrary, showed that meat intake decreased.

Grain and confectionery products

The change in the intake of grain products before and after the pandemic varied based on the type of food. Bertrand et al. (Reference Bertrand, Shaw and Ko62) indicated that the consumption of whole grains was attenuated during the pandemic in a group of University students in Canada. Huber et al. (Reference Huber, Steffen and Schlichtiger52), in a cross-sectional study conducted to assess the impact of lockdown measures on nutrition behaviour of 1980 college students in Germany, showed that the intake of white bread increased primarily in those who increased their overall food intake level.

The intake of confectionery products increased during the pandemic(Reference Palmer, Bschaden and Stroebele-Benschop32,Reference Dragun, Veček and Marendić34,Reference Huber, Steffen and Schlichtiger52,Reference Cheng and Wong64) . Palmer et al. (Reference Palmer, Bschaden and Stroebele-Benschop32) conducted an investigation to assess the lifestyle modifications in a group of university students in Germany during the first COVID-19 lockdown period and showed that 49 % of the participants reported an increase in the consumption of sweets and cakes. Huber et al. (Reference Huber, Steffen and Schlichtiger52) denoted that the increased intake of confectionery products was more pronounced among those who increased their overall food intake during the lockdown. Cheng and Wong(Reference Cheng and Wong64) suggested that this increase could be related to the COVID-19 perceived stress and observed a more pronounced increase in females than males.

Dietary habits

There was an increase in the prevalence of binge eating(Reference Tavolacci, Ladner and Déchelotte35,Reference Flaudias, Iceta and Zerhouni63) , breakfast skipping(Reference Celorio-Sardà, Comas-Basté and Latorre-Moratalla31,Reference Yokoro, Wakimoto and Otaki61,Reference Baquerizo-Sedano, Chaquila and Aguilar65) , cooking(Reference Celorio-Sardà, Comas-Basté and Latorre-Moratalla31,Reference Palmer, Bschaden and Stroebele-Benschop32,Reference Tavolacci, Ladner and Déchelotte35–Reference Sidebottom, Ullevig and Cheever37,Reference Kang, Yun and Lee56) and snacking(Reference Celorio-Sardà, Comas-Basté and Latorre-Moratalla31,Reference Palmer, Bschaden and Stroebele-Benschop32,Reference Tavolacci, Ladner and Déchelotte35,Reference Gallo, Gallo and Young51,Reference Jalal, Beth and Al-Hassan54,Reference Kim and Yeon58,Reference Powell, Lawler and Durham59,Reference Cheng and Wong64,Reference Dun, Ripley-Gonzalez and Zhou66) in various student populations during the pandemic.

Binge eating

The lockdown measures were associated with eating disorders such as binge eating(Reference Tavolacci, Ladner and Déchelotte35,Reference Flaudias, Iceta and Zerhouni63) . Flaudias et al. (Reference Flaudias, Iceta and Zerhouni63) carried out a cross-sectional study on a group of 5738 French students and found an association between stress related to the lockdown and a greater likelihood of binge eating and dietary restriction. The study also found that aside from stress, exposure to Covid-19 related media was associated with eating restriction. Other factors related to binge eating included having an existing eating disorder, being a female, and having high body dissatisfaction. Tavolacci et al. (Reference Tavolacci, Ladner and Déchelotte35), in a repeated cross-sectional study, examined the changes in eating disorders among 8981 university students in France and showed that it was stable between 2009 and 2018 but significantly rose from 31·8 % in 2018 to 51·8 % in 2021 and from 13·0 % in 2009 to 31·3 % in 2021 for women and men, respectively. All types of eating disorders, including binge eating, increased except for restrictive eating disorders among men.

Breakfast skipping and meal timing

College students were skipping breakfast and delaying meal time during the pandemic(Reference Celorio-Sardà, Comas-Basté and Latorre-Moratalla31,Reference Yokoro, Wakimoto and Otaki61,Reference Baquerizo-Sedano, Chaquila and Aguilar65) . Yokoro et al. (Reference Yokoro, Wakimoto and Otaki61) indicated in their study conducted in Japan that the percentage of the study population skipping breakfast during the emergency was significantly higher than the pre-emergency period (26·8 % v. 11 %, respectively); frequencies of skipping lunch and dinner, however, did not change(Reference Yokoro, Wakimoto and Otaki61). Similar findings were observed by Celorio-Sardà et al. (Reference Celorio-Sardà, Comas-Basté and Latorre-Moratalla31) who indicated that 7·2 % of the subjects skipped breakfast while maintaining lunch and dinner in Spain. In addition, Baquerizo-Sedano et al. (Reference Baquerizo-Sedano, Chaquila and Aguilar65) denoted that students were delaying the consumption of many of their main meals.

Cooking

Research strongly indicates an increase in cooking frequency among college students during the pandemic(Reference Celorio-Sardà, Comas-Basté and Latorre-Moratalla31,Reference Palmer, Bschaden and Stroebele-Benschop32,Reference Tavolacci, Ladner and Déchelotte35–Reference Sidebottom, Ullevig and Cheever37,Reference Kang, Yun and Lee56) . Celorio-Sardà et al. (Reference Celorio-Sardà, Comas-Basté and Latorre-Moratalla31) showed that 57 % of the students increased their home cooking practices, and 67 % reported trying new recipes yet most did not change the type of fat used in cooking before and during the pandemic. Silva et al. (Reference Silva, Osborn and Owens36) denoted that most students in their study increased the frequency of cooking meals at home and reduced that of eating out or getting takeout. Kang et al. (Reference Kang, Yun and Lee56) reported an increase in the percentage of students who cooked at least 1 meal/d from 17·6 % in 2019 to 32·9 % in 2020. Palmer et al. (Reference Palmer, Bschaden and Stroebele-Benschop32) indicated that 56·7 % of students in their study reported cooking with fresh ingredients during the pandemic.

Shopping

The pandemic led to modifications in the shopping habits of college students; while many were buying in large quantities due to worry of future food shortages, others reduced their shopping due to financial issues(Reference Celorio-Sardà, Comas-Basté and Latorre-Moratalla31,Reference Silva, Osborn and Owens36,Reference Imaz-Aramburu, Fraile-Bermúdez and Martín-Gamboa53) . Silva et al. (Reference Silva, Osborn and Owens36), in a cross-sectional internet-based study, showed that COVID-19 restriction led to changes in shopping habits of a group of college students in Texas, USA; African American students, in particular, struggled to buy food due to the alterations in their employment status. Studies conducted in Spain, however, showed that the pandemic had a different impact on shopping habits of students(Reference Celorio-Sardà, Comas-Basté and Latorre-Moratalla31,Reference Imaz-Aramburu, Fraile-Bermúdez and Martín-Gamboa53) . Imaz-Aramburu et al. (Reference Imaz-Aramburu, Fraile-Bermúdez and Martín-Gamboa53) observed, in their study, a higher frequency of food purchases especially vegetables. Furthermore, Celorio-Sardà et al. (Reference Celorio-Sardà, Comas-Basté and Latorre-Moratalla31) indicated that 39 % of students in their study reported a greater purchase of local products compared with pre-pandemic.

Snacking

College students increased the frequency of unhealthy snacking during the pandemic(Reference Celorio-Sardà, Comas-Basté and Latorre-Moratalla31,Reference Palmer, Bschaden and Stroebele-Benschop32,Reference Tavolacci, Ladner and Déchelotte35,Reference Gallo, Gallo and Young51,Reference Jalal, Beth and Al-Hassan54,Reference Kim and Yeon58,Reference Powell, Lawler and Durham59,Reference Cheng and Wong64,Reference Dun, Ripley-Gonzalez and Zhou66) . Gallo et al. (Reference Gallo, Gallo and Young51) showed that the frequency of intake of energy-dense snacks increased in a population of Australian university female students; no significant change was observed in males. Celorio-Sardà et al. (Reference Celorio-Sardà, Comas-Basté and Latorre-Moratalla31) denoted in their study an increase in the intake of foods such as salty snacks, homemade pastries and chocolate, and a change in timing of snacks; almost 50 % of the study population ceased the intake of a midmorning snack while over 53 % started consuming a late-night snack before bedtime. Cheng and Wong(Reference Cheng and Wong64) reported that students who were more stressed engaged in emotional eating and consumed high palatability and energy-dense snacks.

Ordering fast food

The evidence, albeit meagre, has displayed a decrease in the frequency of ordering and consuming fast food meals among college students during the pandemic(Reference Palmer, Bschaden and Stroebele-Benschop32,Reference Al-Musharaf, Aljuraiban and Bogis48,Reference Jalal, Beth and Al-Hassan54) . Al-Musharaf et al. (Reference Al-Musharaf, Aljuraiban and Bogis48) conducted a prospective study to evaluate the lifestyle changes of students before and during lockdown in Saudi Arabia and showed that 81 % of participants decreased their fast-food intake during the pandemic.

Weight gain prevalence

As displayed in Table 1, we found that fifteen studies have met the inclusion criteria and assessed weight change among college students during the early phase of the pandemic. Most of these investigations were cross-sectional and assessed self-reported weight change via online surveys. Students had to report their current weight and recall their pre-pandemic weight status(Reference Millán-Jiménez, Herrera-Limones and López-Escamilla30–Reference Tavolacci, Ladner and Déchelotte35,Reference Kim and Yeon58,Reference Baquerizo-Sedano, Chaquila and Aguilar65,Reference Tan, Tan and Tan67–Reference Chaturvedi, Vishwakarma and Singh69) .

Table 1. Findings of studies related to impact of COVID-19 pandemic on students’ body weight

In studies conducted in Spain, no less than 30 % of students gained weight during confinement(Reference Millán-Jiménez, Herrera-Limones and López-Escamilla30,Reference Celorio-Sardà, Comas-Basté and Latorre-Moratalla31) . Weight gain was also observed in other European countries such as Germany(Reference Palmer, Bschaden and Stroebele-Benschop32), Romania(Reference Stanila, Oravitan and Matichescu33), Croatia(Reference Dragun, Veček and Marendić34) and France(Reference Tavolacci, Ladner and Déchelotte35). Tavolacci et al. (Reference Tavolacci, Ladner and Déchelotte35) conducted repeated cross-sectional studies in France and showed that between 2009 and 2021, the prevalence of overweight and obesity significantly increased from 8·8 to 13·3 % in women and from 4·0 to 9·5 % in men, respectively. In China, two retrospective studies were carried out to measure body weight change between the period preceding the lockdown (December 2019 – January 2020) to after the end of the lockdown (May 2020)(Reference Dun, Ripley-Gonzalez and Zhou66,Reference Jia, Zhang and Yu70) . Jia et al. (Reference Jia, Zhang and Yu70), for instance, indicated that the prevalence of overweight and obesity in their study population increased from 21·4 % to 24·6 % and from 10·5 % to 12·6 %, respectively. The percentage of weight gain was even more pronounced in the study populations in other Asian countries such as India(Reference Chaturvedi, Vishwakarma and Singh69), Korea(Reference Kim and Yeon58), Malaysia and Indonesia(Reference Tan, Tan and Tan67), with no less than 35 % of students gaining weight during the pandemic. Countries in South America such as Peru(Reference Baquerizo-Sedano, Chaquila and Aguilar65) and Brazil(Reference da Mota Santana, Milagres and Dos Santos68) showed that no less than half of the student populations gained weight during the pandemic. Other investigations did not display the prevalence of weight gain but did indicate an increase the students’ body weight(Reference Brancaccio, Mennitti and Gentile50,Reference Tran, Dinh and Nguyen71) . Brancaccio et al. (Reference Brancaccio, Mennitti and Gentile50) showed that, in Italy, there was a modest increase in mean body weight from 67·4 ± 14·9 kg to 68·0 ± 15·2 kg before and after the beginning of the quarantine, respectively.

Factors associated with weight gain

Gender

Studies have shown that male college students were more likely to gain weight than female college students during the pandemic(Reference Stanila, Oravitan and Matichescu33,Reference Tavolacci, Ladner and Déchelotte35,Reference Brancaccio, Mennitti and Gentile50,Reference da Mota Santana, Milagres and Dos Santos68) . In a cross-sectional study involving a group of participants from the University of Naples Federico II (Italy), Brancaccio et al. (Reference Brancaccio, Mennitti and Gentile50) showed that body weight increased more significantly among males than females which was related to the higher consumption of take-away food and alcohol. Stanila et al. (Reference Stanila, Oravitan and Matichescu33) also denoted an association between high alcohol intake among males and an increase in body weight during the pandemic.

Diet

The unfavourable changes in diet quality and dietary habits were directly associated with weight gain(Reference Palmer, Bschaden and Stroebele-Benschop32,Reference Boukrim, Obtel and Kasouati49,Reference Brancaccio, Mennitti and Gentile50,Reference Jalal, Beth and Al-Hassan54,Reference da Mota Santana, Milagres and Dos Santos68) . Foods that were strong predictors of weight gain included take-away foods, alcohol(Reference Brancaccio, Mennitti and Gentile50), refined carbohydrates such as pasta, sweets including cake, savoury snacks(Reference Palmer, Bschaden and Stroebele-Benschop32) and fast and fried foods(Reference Jalal, Beth and Al-Hassan54). When it comes to dietary patterns, da Mota Santana et al. (Reference da Mota Santana, Milagres and Dos Santos68) indicated, in a cross-sectional study involving students from four universities in Brazil, that processed and ultra-processed dietary patterns (based mainly on processed and ultra-processed foods, respectively) were a major risk factor for obesity during the pandemic.

Lack of physical activity

Sedentary behaviour exacerbated the risk of weight gain during the pandemic, especially when the lockdown was first set forth. Baquerizo-Sedano et al. (Reference Baquerizo-Sedano, Chaquila and Aguilar65) carried out a study to assess the effect of 12-week confinement on body weight of 521 university students and showed that for every 1 h-increase in sedentarism, there was a 0·3 % increase in body weight. Screen exposure time was another factor associated with weight gain during the confinement(Reference Tan, Tan and Tan67). Tan et al. (Reference Tan, Tan and Tan67) showed in their study population that Malaysian and Indonesian students spent 9·16 h/d and 7·85 h/d, respectively, in sedentary behaviour during home confinement. López-Valenciano et al. (Reference López-Valenciano, Suárez-Iglesias and Sanchez-Lastra44) indicated that college students from different countries in their study reduced their level of walking, along with moderate, vigorous, and total physical activity levels during the COVID-19 pandemic confinements. Nevertheless, students who met the current minimum physical activity recommendations preceding lockdown continued to meet them during the confinements. Physical inactivity could also be related to the increased sitting time associated with remote learning and working from home which in-return increased the risk of weight gain(Reference Dun, Ripley-Gonzalez and Zhou66,Reference Tan, Tan and Tan67) .

Weight status pre-pandemic

Weight status preceding the pandemic was a risk factor for obesity during the pandemic; those who were obese/overweight before the confinement were at higher risk of increasing their food intake considerably during the lockdown and thus gained more weight(Reference Huber, Steffen and Schlichtiger52).

Sleep quality

The pandemic has been associated with reduced sleep quality and duration among the college student population which in return increased the risk of obesity(Reference Wang, Chen and Liu72). Baquerizo-Sedano et al. (Reference Baquerizo-Sedano, Chaquila and Aguilar65) indicated that for every hour of increase in sleep duration, there was a 0·2 % decrease in body weight.

Meal timing

Research suggests that the pandemic led to delays in meal timing(Reference Sinha, Pande and Sinha73). This delay, according to a study by Baquerizo-Sedano et al. (Reference Baquerizo-Sedano, Chaquila and Aguilar65), was associated with a twofold increase in obesity among college students.

Food insecurity

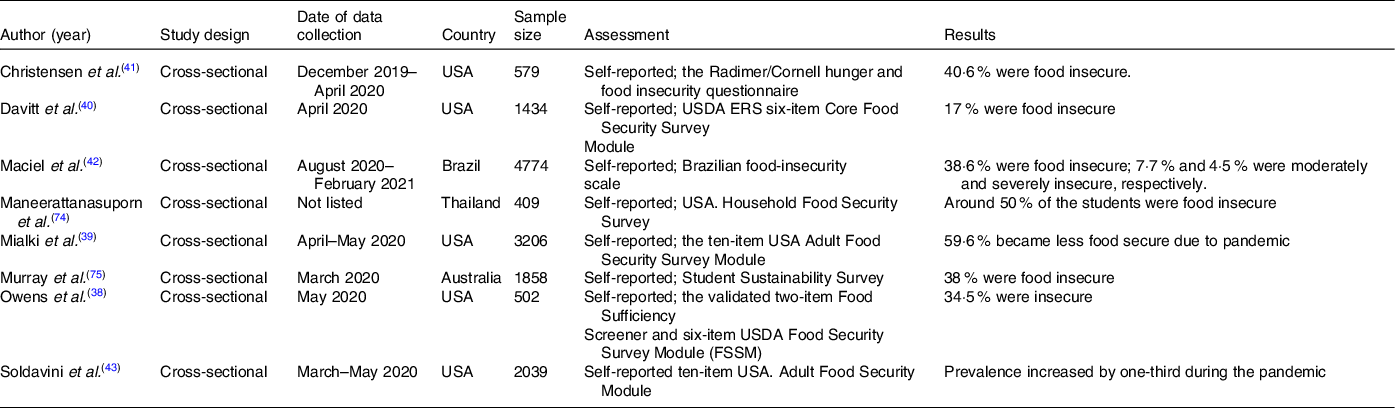

Research suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic affected the students’ abilities to attain food and increased the prevalence of food insecurity(Reference Silva, Osborn and Owens36–Reference Soldavini, Andrew and Berner43). Table 2 displays the prevalence of food insecurity during the early phase of the pandemic. In studies conducted in the USA(Reference Owens, Brito-Silva and Kirkland38,Reference Mialki, House and Mathews39,Reference Christensen, Forbush and Richson41,Reference Soldavini, Andrew and Berner43) , Brazil(Reference Maciel, Lyra and Gomes42), Thailand(Reference Maneerattanasuporn, Techakriengkrai and Jamphon74) and Australia(Reference Murray, Peterson and Primo75), over 30 % of students were food insecure. Mialki et al. (Reference Mialki, House and Mathews39) denoted that 59·6 % of students became less food secure due to the pandemic in the USA. Sidebottom et al. (Reference Sidebottom, Ullevig and Cheever37) indicated that there was an increase of 54 % in the number of students not able to afford healthy food or balanced meals and an increase of 68 % in the number of those who started skipping meals or consuming less food due to lack of resources during the pandemic. Food insecurity was even more pronounced among minorities than non-minorities(Reference Silva, Osborn and Owens36,Reference Mialki, House and Mathews39,Reference Maneerattanasuporn, Techakriengkrai and Jamphon74) . Silva et al. (Reference Silva, Osborn and Owens36) indicated that Black students were more likely to report changes in their ability to access sufficient healthy food. Davitt et al. (Reference Davitt, Heer and Winham40) reported that 17 % of students were food insecure during the pandemic. This lower level of food insecurity prevalence compared with other studies could be partly related to the high number of students who moved back with their parents during the pandemic and thus had access to additional family resources. Factors that predicted food insecurity among college students during the pandemic included loss or reduction of employment, receipt of financial aid, furlough, alterations in living arrangements and housing status, lower cooking self-efficacy, consumption of more take-out or fast food, low diet quality, pre-COVID-19 financial status, the non-White ethnicity and closure of college campuses(Reference Owens, Brito-Silva and Kirkland38–Reference Soldavini, Andrew and Berner43,Reference Maneerattanasuporn, Techakriengkrai and Jamphon74) .

Table 2. Findings of studies related to impact of COVID-19 pandemic on students’ food insecurity status

Discussion

The diet quality of college students was compromised(Reference Silva, Osborn and Owens36,Reference Jia, Liu and Xie55,Reference Kilani, Bataineh and Al-Nawayseh57,Reference Bertrand, Shaw and Ko62) during the pandemic in many nations due to the decrease in the intake of whole grains(Reference Bertrand, Shaw and Ko62), dairy products(Reference Dragun, Veček and Marendić34,Reference Boukrim, Obtel and Kasouati49,Reference Jia, Liu and Xie55,Reference Bertrand, Shaw and Ko62,Reference Cheng and Wong64) , legumes(Reference Jia, Liu and Xie55), nuts(Reference Bertrand, Shaw and Ko62), fruits and vegetables(Reference Sidebottom, Ullevig and Cheever37,Reference Jia, Liu and Xie55,Reference Bertrand, Shaw and Ko62,Reference Cheng and Wong64) and the increase in consumption of alcohol(Reference Sidebottom, Ullevig and Cheever37,Reference Brancaccio, Mennitti and Gentile50,Reference Bertrand, Shaw and Ko62) , confectionery products(Reference Palmer, Bschaden and Stroebele-Benschop32,Reference Dragun, Veček and Marendić34,Reference Huber, Steffen and Schlichtiger52,Reference Cheng and Wong64) and refined grains(Reference Huber, Steffen and Schlichtiger52). Nevertheless, the lockdown had the opposite effect on the diet quality in countries that adopted the Mediterranean dietary pattern(Reference Celorio-Sardà, Comas-Basté and Latorre-Moratalla31,Reference Dragun, Veček and Marendić34,Reference Imaz-Aramburu, Fraile-Bermúdez and Martín-Gamboa53) . The increased intake of fruits and vegetables in Spain, for instance, could be partially explained by their low prices, the growth in their production and accessibility(76), the higher frequency of food purchases(Reference Rodríguez-Pérez, Molina-Montes and Verardo60,Reference Di Renzo, Gualtieri and Pivari77) , the increased health perception and the emphasis on eating healthy during the pandemic to boost the immunity and prevent severe disease effects(Reference Rodríguez-Pérez, Molina-Montes and Verardo60,Reference Muscogiuri, Barrea and Savastano78) . The reduction in alcohol intake(Reference Millán-Jiménez, Herrera-Limones and López-Escamilla30,Reference Celorio-Sardà, Comas-Basté and Latorre-Moratalla31) could also be explained by the increase in health awareness and by its association with leisure activities. The restriction of leisure activities during the pandemic led to a decrease in alcohol intake since students had less opportunities to meet for drinks(Reference Kang, Yun and Lee56).

The reduction in diet quality observed in many nations, however, could be a concomitant of unfavourable changes in dietary habits of college students such as binge eating,(Reference Tavolacci, Ladner and Déchelotte35,Reference Flaudias, Iceta and Zerhouni63) , breakfast skipping(Reference Celorio-Sardà, Comas-Basté and Latorre-Moratalla31,Reference Yokoro, Wakimoto and Otaki61) and increased snacking frequency of unhealthy food items(Reference Celorio-Sardà, Comas-Basté and Latorre-Moratalla31,Reference Palmer, Bschaden and Stroebele-Benschop32,Reference Tavolacci, Ladner and Déchelotte35,Reference Gallo, Gallo and Young51,Reference Jalal, Beth and Al-Hassan54,Reference Kim and Yeon58,Reference Powell, Lawler and Durham59,Reference Cheng and Wong64,Reference Dun, Ripley-Gonzalez and Zhou66) . These changes could be partially explained by the rise in the prevalence of pandemic-related mental conditions including stress, depression and anxiety(Reference Jehi, Khan and Dos Santos79), along with other factors such as boredom(Reference Gallo, Gallo and Young51,Reference Cheng and Wong64) and food insecurity(Reference Sidebottom, Ullevig and Cheever37). Other dietary habits, however, such as cooking frequency improved during the pandemic(Reference Celorio-Sardà, Comas-Basté and Latorre-Moratalla31,Reference Palmer, Bschaden and Stroebele-Benschop32,Reference Tavolacci, Ladner and Déchelotte35–Reference Sidebottom, Ullevig and Cheever37,Reference Davitt, Heer and Winham40,Reference Kang, Yun and Lee56) , which could be related to the closure of on-campus cafeterias and restaurants, boredom and fear of infection from eating out/ordering foods(Reference Silva, Osborn and Owens36). Nevertheless, there was an increase in the total amount of energy intake(Reference Gallo, Gallo and Young51,Reference Jalal, Beth and Al-Hassan54) , which, along with the modifications in the dietary quality and habits, led to unfavourable weight changes. Studies have shown that no less than 20 to 30 % of students gained weight during the pandemic(Reference Millán-Jiménez, Herrera-Limones and López-Escamilla30,Reference Celorio-Sardà, Comas-Basté and Latorre-Moratalla31,Reference Kim and Yeon58,Reference Tan, Tan and Tan67,Reference Chaturvedi, Vishwakarma and Singh69) , and this was related to factors such as the male gender(Reference Stanila, Oravitan and Matichescu33,Reference Tavolacci, Ladner and Déchelotte35,Reference Brancaccio, Mennitti and Gentile50,Reference da Mota Santana, Milagres and Dos Santos68) , increased intake of refined carbohydrates, alcohol, fats, and take away foods (Reference Palmer, Bschaden and Stroebele-Benschop32), increased snacking (Reference Palmer, Bschaden and Stroebele-Benschop32), reduced sleep quality(Reference Baquerizo-Sedano, Chaquila and Aguilar65), delay in meal-timing(Reference Baquerizo-Sedano, Chaquila and Aguilar65), low levels of physical activity(Reference Huber, Steffen and Schlichtiger52,Reference Baquerizo-Sedano, Chaquila and Aguilar65–Reference Tan, Tan and Tan67) and food insecurity(Reference Owens, Brito-Silva and Kirkland38).

COVID-19 pandemic affected the students’ abilities to attain food and increased the prevalence of food insecurity among this population(Reference Silva, Osborn and Owens36–Reference Maciel, Lyra and Gomes42), with over 30 % of students being food insecure in the USA(Reference Owens, Brito-Silva and Kirkland38,Reference Mialki, House and Mathews39,Reference Christensen, Forbush and Richson41) , Brazil(Reference Maciel, Lyra and Gomes42), Thailand(Reference Maneerattanasuporn, Techakriengkrai and Jamphon74) and Australia(Reference Murray, Peterson and Primo75). Factors that predicted food insecurity among college students during the pandemic included loss or reduction of employment, receipt of financial aid, furlough, alterations in living arrangements and housing status, lower cooking self-efficacy, consumption of more take-out or fast food, low diet quality, pre-COVID-19 financial status, the non-White ethnicity and closure of college campuses(Reference Owens, Brito-Silva and Kirkland38–Reference Maciel, Lyra and Gomes42,Reference Maneerattanasuporn, Techakriengkrai and Jamphon74) .

The pandemic was associated with emotional eating among the college population(Reference Cheng and Wong64) which has been linked with the replacement of healthy foods with comfort foods rich in saturated fats and refined carbohydrates. These changes could have resulted in an insufficient dietary fibre(Reference Turner and Lupton80) and phytochemicals intake(Reference Carnauba, Chaves and Baptistella81).

The sudden changes in the students’ lifestyle during the pandemic could affect their health by elevating their risk of various chronic diseases. The reduction in physical activity levels, the unhealthy dietary habits such as skipping meals and snacking, along with the simultaneous weight gain, have been shown to be associated with an increased risk of dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, chronic systemic inflammation, hypertension(Reference St-Onge, Ard and Baskin82,Reference Rodríguez-Hernández, Simental-Mendía and Rodríguez-Ramírez83) and CVD(Reference Takagi, Hari and Nakashima84). Food insecurity also increases the risk of chronic conditions such as obesity and diabetes(Reference Laraia85). Additionally, food insecurity is associated with eating disorder – related impairment, binge eating and compensatory fasting(Reference Christensen, Forbush and Richson41).

The findings of this literature review offer public health professionals and policymakers valuable information on the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on students’ diet quality and dietary habits, which can assist them to be better prepared and take effective action during future outbreaks. Governments and academic institutions should ensure that students’ dietary behaviours are not compromised during the pandemic by raising awareness and placing a strong emphasis on the urgency of adopting a healthy dietary pattern(Reference Reshma, Priya and Gayathri86). Nutrition education interventions should be offered through various media outlets(Reference Deliens, Van Crombruggen and Verbruggen87) and entrenched in school curricula(Reference Dudley, Cotton and Peralta88) to instruct the students on the importance of cooking, increasing the consumption of fruits, vegetables, whole grains and fish, and avoiding unhealthy behaviours such as binge drinking, snacking and breakfast skipping. A meta-analysis by Deliens et al. (Reference Deliens, Van Crombruggen and Verbruggen87) showed that nutrition education, improvement of self-regulation towards dietary intake and point-of-purchase messaging strategies, could enhance the students’ dietary intake. Mental health support must be provided through counselling centers free of charge to help students cope with anxiety, depression and stress without resorting to emotional eating during the pandemic(Reference Cheng and Wong64).

The findings of this review also suggest that weight gain, a manifestation of unhealthy lifestyle behaviours, should be addressed. Even amid a complete lockdown, universities should offer weight-loss counselling services, educate the students on various weight management guidelines and heavily encourage the students to engage in outdoor physical activities such as hiking, biking, swimming, etc.(Reference Al-Musharaf, Aljuraiban and Bogis48). The faculty has a critical role to play by building and implementing online curricula designed to promote healthful eating to students of any major(Reference Frantz, Munroe and McClave89). The online lessons should place emphasis on improving the behaviours, attitudes and self-efficacy of students to help them amend their diets and achieve weight management goals during the pandemic(Reference Greene, White and Hoerr90).

This review also highlights the need to mitigate college students’ food insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic by implementing a robust, comprehensive policy response. This entails expanding the eligibility of governmental economic relief efforts to involve students, increasing access to healthy foods by raising awareness of food assistance programs and establishing food banks and food pantries near university campuses to support students during challenging times(Reference Owens, Brito-Silva and Kirkland38).

According to the International Food Policy Research Institute, there had been a global food price crises with a dramatic surge in the prices of staple foods such as rice, beans, maize and soybeans. This has been a concern especially for low-income countries due to their governments’ limited ability to protect the purchasing power of their underserved communities and prevent the high food prices from leading to food insecurity and altering diet quality(Reference Vos, Glauber and Hernández91). To fight food insecurity, especially in developing countries, it is crucial to place emphasis on commodities’ distribution and supply chain management system(Reference Bairagi, Mishra and Mottaleb92). Necessary policy actions should be taken by the governments to stabilise food prices during pandemics. These include supplying markets during pandemics with staple foods from the public food distribution system(Reference Bairagi, Mishra and Mottaleb92). Furthermore, policies should be established to prevent the sellers from raising the prices of foods during such crises(Reference Bairagi, Mishra and Mottaleb92).

To our knowledge, this review is the first to take a comprehensive approach to identifying peer-reviewed journal articles published globally that delve into the effect of COVID-19 on dietary habits, diet quality, food insecurity prevalence and body weight changes of college students. It also drew from existing literature to present and consolidate the evidence for the various factors associated with the high prevalence of food insecurity and obesity among students during the pandemic. However, most of the displayed findings were generated from cross-sectional investigations which render it challenging to assess causality and make robust conclusions(Reference Millán-Jiménez, Herrera-Limones and López-Escamilla30–Reference Silva, Osborn and Owens36,Reference Owens, Brito-Silva and Kirkland38–Reference Soldavini, Andrew and Berner43,Reference Boukrim, Obtel and Kasouati49,Reference Huber, Steffen and Schlichtiger52,Reference Jia, Liu and Xie55,Reference Kim and Yeon58,Reference Flaudias, Iceta and Zerhouni63,Reference Baquerizo-Sedano, Chaquila and Aguilar65,Reference Tan, Tan and Tan67–Reference Chaturvedi, Vishwakarma and Singh69,Reference Maneerattanasuporn, Techakriengkrai and Jamphon74) . Nevertheless, findings from various longitudinal studies also confirmed a significant increase in body weight of college students during the pandemic(Reference Al-Musharaf, Aljuraiban and Bogis48,Reference Jalal, Beth and Al-Hassan54,Reference Dun, Ripley-Gonzalez and Zhou66,Reference Jia, Zhang and Yu70) and a decrease in diet quality(Reference Jalal, Beth and Al-Hassan54,Reference Jia, Liu and Xie55) . Another limitation is the use of self-reported measures, in most of the studies, to assess and determine changes in diet quality(Reference Celorio-Sardà, Comas-Basté and Latorre-Moratalla31,Reference Palmer, Bschaden and Stroebele-Benschop32,Reference Jia, Liu and Xie55,Reference Rodríguez-Pérez, Molina-Montes and Verardo60) , dietary habits(Reference Palmer, Bschaden and Stroebele-Benschop32,Reference Brancaccio, Mennitti and Gentile50,Reference Gallo, Gallo and Young51,Reference Rodríguez-Pérez, Molina-Montes and Verardo60) and body weight(Reference Millán-Jiménez, Herrera-Limones and López-Escamilla30–Reference Tavolacci, Ladner and Déchelotte35,Reference Al-Musharaf, Aljuraiban and Bogis48,Reference Huber, Steffen and Schlichtiger52,Reference Kim and Yeon58,Reference Baquerizo-Sedano, Chaquila and Aguilar65,Reference Tan, Tan and Tan67–Reference Chaturvedi, Vishwakarma and Singh69) along with the prevalence of food insecurity(Reference Silva, Osborn and Owens36,Reference Owens, Brito-Silva and Kirkland38–Reference Soldavini, Andrew and Berner43,Reference Maneerattanasuporn, Techakriengkrai and Jamphon74,Reference Murray, Peterson and Primo75) . When it comes to diet, for instance, most investigations relied on one survey administered at one-time point to measure intake during the pandemic and compare it retrospectively with pre-pandemic times, which may possibly be subjected to recall bias(Reference Celorio-Sardà, Comas-Basté and Latorre-Moratalla31,Reference Brancaccio, Mennitti and Gentile50,Reference Jia, Liu and Xie55) . Other studies based dietary analyses on a single 24-h recall instead of repeated recalls and thus might have failed to capture usual intake(Reference Gallo, Gallo and Young51). Since no training was provided to participants, their perception of food portions could have led to an under/over-estimation of their actual intake(Reference Rodríguez-Pérez, Molina-Montes and Verardo60). Furthermore, most studies on dietary intake and habits did not conduct nutrient analysis at the level of the macro and micronutrient but exclusively assessed the intake of foods and food groups during the pandemic(Reference Celorio-Sardà, Comas-Basté and Latorre-Moratalla31,Reference Palmer, Bschaden and Stroebele-Benschop32,Reference Sidebottom, Ullevig and Cheever37,Reference Boukrim, Obtel and Kasouati49,Reference Cheng and Wong64) . The majority of the studies collected body weight data by self-reporting tools such as online questionnaires instead of weight scales which could have led to social desirability bias and memory recall bias(Reference Palmer, Bschaden and Stroebele-Benschop32,Reference Al-Musharaf, Aljuraiban and Bogis48) . When it came to assessing the prevalence of food insecurity, various studies used a convenience sample which might have impacted the generalisability of the findings(Reference Mialki, House and Mathews39,Reference Davitt, Heer and Winham40) .

Our systematic review has limitations. For instance, we did not contact relevant experts to include data from unpublished manuscripts and thus our systematic review might be subjected to publication bias(Reference Dalton, Bolen and Mascha93). Furthermore, we might have missed a number of articles published on this topic due to a lack of access to databases such as Web of Science. Nevertheless, by following inclusive search strategies, we made extensive efforts to identify all relevant published studies.

It is recommended, from a research standpoint, to conduct longitudinal investigations to assess the long-term effects of the pandemic on the dietary habits, body weight and food security status of students in case of subsequent pandemic waves. These studies should rely on direct means of measuring body weight such as weight scales and diet such as repeated 24-h recalls(Reference Freedman, Midthune and Arab94). This would lead to more robust conclusions regarding the cause-and-effect relationships between the different factors presented in this review and these outcomes among higher education students. Furthermore, additional research should be conducted to explore the effect of the pandemic on the macro and micro-nutrient levels among college students.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 outbreak has exacerbated the students’ diet quality and placed them at high risk of food insecurity. Students engaged in unfavourable dietary habits such as binge eating, breakfast skipping and unhealthy snacking. This, along with other factors such as the male gender, reduced sleep quality, lack of physical activity, pre-pandemic weight status and meal-timing loneliness, have increased the susceptibility of college students to weight gain. Thus, higher education institutions and governments should improve students’ access to nutritious foods and implement nutrition education interventions through the school curricula to instruct the students on the importance of following a healthy dietary pattern. In case of future outbreaks, it would also be recommended to conduct longitudinal investigations to assess the long-term effects of the pandemic on the dietary habits, body weight and food security status of students.

Acknowledgements

None.

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conceptualization: T.J., R.K., R.H., and H.D.S; Investigation: T.J., R.K., R.H., and H.D.S; Supervision: T.J.; Writing - original draft: T.J. and R.K.; Writing - review and editing: T.J., R.K., R.H., and H.D.S.

There are no conflicts of interest.