Diet-related, chronic health problems remain a significant public health issue throughout much of the USA(Reference Ames and Burke1–Reference Satia3), with a disproportionate impact on American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) populations(Reference Slattery, Ferucci and Murtaugh4–Reference Hutchinson and Shin9). Such health problems in AI/AN populations include high rates of paediatric and adult obesity, high rates of development of type II diabetes and high rates of development of CVD(Reference Hutchinson and Shin9). Factors including low food security, geographic isolation and the loss of traditional foods and lifestyles have all contributed to less healthy diets within AI/AN communities and have been linked to the development of these diet-related health problems(Reference Jernigan, Huyser and Valdes10–Reference Lombard, Beresford and Ornelas12). In addition, the economic burden of treating diet-related health problems within medically resource-constrained environments faced by many AI/AN communities further compounds existent disparities(Reference Schneider13). As such, there exists an urgent need for innovative, multi-level and cross-sectorial strategies to address diet-related health problems in AI/AN populations, while simultaneously utilising and promoting AI/AN communities’ inherent, existing resources(Reference Gittelsohn and Rowan14,Reference Gittelsohn and Trude15) .

Navajo Nation, belonging to the Navajo (Diné) people, is the largest AI/AN reservation in the USA and is almost entirely a USDA-designated food desert(16). Navajo Nation’s land base extends into three states (New Mexico, Arizona and Utah), covering approximately 27 000 square miles. According to 2010 US census data, 332 129 individuals were identified as Navajo alone or in combination with another racial/ethnic group, with approximately 47 % living within Navajo Nation. The land is sovereign to the Navajo people and is governed by a three-branch system with legislative representation from 110 chapters/communities that make up the nation(17). Recent examination in Navajo Nation has revealed the highest rate of food insecurity reported within the US(Reference Pardilla, Prasad and Suratkar18). Low food security on Navajo Nation has been tied to high unemployment and geographic isolation, with sparse grocery establishments(Reference Mullany, Neault and Tsinge19). Families living on or near Navajo Nation who face substantial economic constraints and limited geographic access to healthy foods are thus motivated to purchase cheaper, energy-dense, low-nutrient foods with longer shelf lives(Reference Gittelsohn, Kim and He20,Reference Pardilla, Prasad and Suratkar21) . Commodity food dependence that developed due to historical forced assimilation and loss of both right and ability to harvest traditional foods have also contributed to a reduced consumption of healthier foods.

One strategy towards mitigating the effects of diet-related health problems involves increasing community access to fruits and vegetables. Indeed, previous studies have observed higher rates of diet-related health problems in populations with lower consumption of fruits and vegetables(Reference Stroehla, Malcoe and Velie22,Reference Sinley and Albrecht23) . The use of fruit and vegetable voucher programmes, which assist individuals and families at risk of diet-related health problems to purchase healthy foods, demonstrate trends towards increased consumption of fruits and vegetables among those receiving the intervention(Reference Bihan, Mejean and Castetbon24–Reference Herman, Harrison and Jenks26). Such programmes have typically targeted urban, low-income populations and have not previously been widely developed within a tribal community.

The Community Outreach and Patient Empowerment (COPE) Programme, a sister organisation of Partners In Health, initiated the Navajo Fruit and Vegetable Prescription Programme (Navajo FVRx) in 2014 to improve access to fruits and vegetables among Navajo families and community members. Through robust partnerships, Navajo FVRx aims to link existing health infrastructure and commercial food infrastructure, while simultaneously supporting growth within both frameworks. Navajo FVRx was also designed with the objective of amplifying a growing community-based effort to reclaim the use of traditional foods through strengthening food production systems, as well as through education related to nutrition and food preparation. Ultimately, the programme is intended to improve access and knowledge about healthy produce and traditional foods in order to combat diet-related health problems on Navajo Nation. The programme is also designed to strengthen the effectiveness of inter-professional healthcare teams and improve the quality of healthcare delivery to families, thus increasing both healthcare provider and patient/family satisfaction. Here, we describe a community-based participatory methodology used in the inception, design and implementation of Navajo FVRx and offer key lessons learned from the process.

Methods

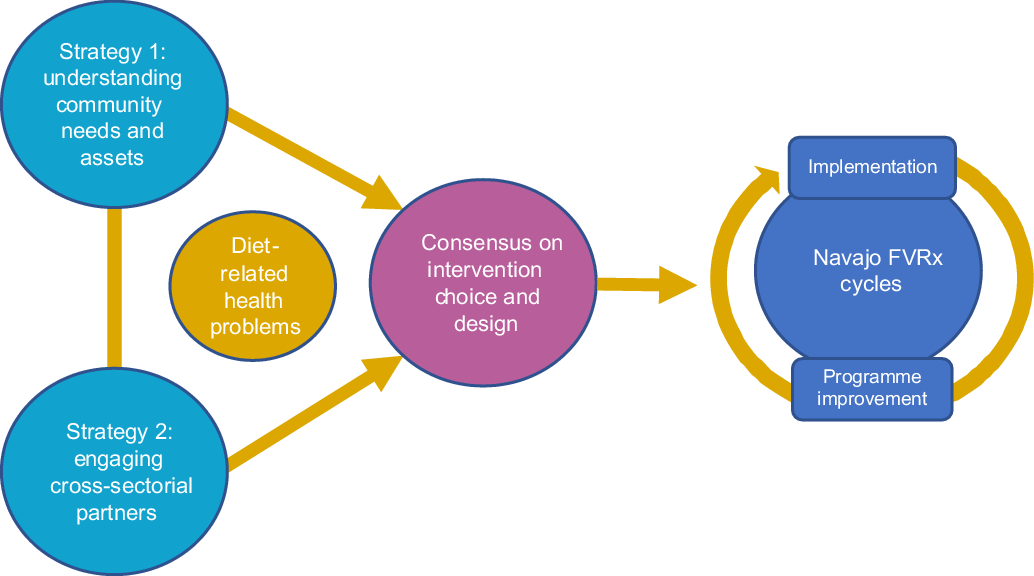

COPE is a native-controlled, community-based organisation that has partnered with healthcare providers, community outreach programmes and stakeholders since 2009 to address health disparities existent on Navajo Nation. The organisation has utilised a community-based participatory approach, informed by a socio-ecological lens focused on AI/AN populations. This approach incorporates community, government and academic partnerships to address the complex socio-economic and cultural interactions that have resulted in many health issues faced by Navajo communities. The development (phase I) of Navajo FVRx was informed by two inter-related strategies focused on diet-related health problems on Navajo Nation, often occurring simultaneously: (1) understanding the needs and inherent resources of Navajo communities and (2) engaging cross-sectorial partners on intervention choice and design. Once consensus was reached on the initial design of the programme, the programme was implemented (phase II) with cyclical adaptations to respond to lessons learned, feedback from partners and families, and to better fit local context and changing needs (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Schematic displaying the Community Outreach and Patient Empowerment community-based participatory approach to development, implementation and refinement of Navajo Fruit and Vegetable Prescription (FVRx). Two simultaneous strategies were used to consider diet-related health problems on Navajo Nation, leading to the FVRx intervention design. Implementation has involved regular programme improvement based on elicited partner and community feedback

Phase I: programme planning and design

Strategy 1: understanding community needs and assets

While diet-related, chronic health problems have been steadily rising within AI/AN populations in general, children and pregnant women have been found to be particularly vulnerable(Reference Anderson and Whitaker27–Reference Acton, Burrows and Wang29). Notably, both children and women of childbearing age have been shown to benefit from intensive lifestyle-related interventions(Reference Fagg, Chadwick and Cole30–Reference Ratner, Christophi and Metzger32). Drawing from published literature, local data and a community needs assessment collected in collaboration with community and national partners, COPE and partners ultimately focused on pre-school aged children and pregnant women as populations most suitable for introduction of an intervention. Here, we describe the process and timeline of understanding both community needs and assets as they pertain to diet-related health problems on Navajo Nation, informing the development of Navajo FVRx.

Identifying nutritional needs of the general community (2012–2014)

Through partnership with Navajo Community Health Representatives (CHR operate similarly to many community health worker programmes worldwide. The programme was established in 1968 with the goal of improving health within Navajo communities through home healthcare delivery, education and community health programmes, organised in coordination with tribal and Indian Health Service programmes. The programme is estimated to provide services to approximately 21 000 individuals living on or near Navajo Nation (http://www.nndoh.org/chr.html).) working in eastern Navajo Nation, between 2012 and 2013 COPE completed a community needs assessment(Reference VanWassenhove-Paetzold, Rajashekara and Shin33,Reference Rajashekara and Shin34) . The needs assessment involved a community survey followed by in-depth interviews of adult community members, including Crownpoint Chapter House officials, CHR and local heads of households. Survey results most impactful to intervention development included the findings that 57 % of 253 respondents felt that those in their home did not have enough fruits and vegetables, with 61 % reporting expense of healthy foods as a major barrier. Federal food assistance programmes were commonly used, with 25 % of households participating in the Food Distribution Programme on Indian Reservations, 40 % of households enrolled in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Programme and 12 % of households using the Special Supplemental Nutrition Programme for Women, Infants, and Children. While our survey targeted a broad array of households, among Navajo mothers eligible for Women, Infants, and Children, approximately 70 % are enrolled in the programme(35).

In 2014, COPE additionally conducted consumer preference surveys in eastern Navajo Nation in several communities – one at a popular flea market, another at a remote chapter house alongside a mobile grocery unit(Reference VanWassenhove-Paetzold, Rajashekara and Shin33). Participants who completed a survey were offered a selection of fruits and vegetables. Of fifty-five respondents, highest preferences for fruits and vegetables included lettuce, peaches, onion, cucumbers, apples, chillies, strawberries and oranges. More than half of the respondents (55 %) were willing to shop weekly or more frequently for produce, though 71 % of respondents preferred to travel by car no longer than 30 min to shop. Approximately half (51 %) of the respondents reported travelling more than an hour to the place where the majority of their food was purchased.

Identifying target groups for a nutritional interventions (2012–2014)

Pregnant mothers were identified as an important target population for nutritional intervention based on anecdotal suggestions from local healthcare providers as well as findings from the Navajo Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System conducted between 2005 and 2011. This was a population-based surveillance system developed and sponsored by the CDC and implemented by New Mexico Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System(35). Findings demonstrated that 14 % of Navajo mothers developed diabetes during pregnancy and that 3 % of mothers had existing diabetes before pregnancy. Closely related, 20 % of Navajo mothers reported that they did not always have enough food to eat during pregnancy. Fifty-seven percentage of Navajo mothers had a BMI percentile that indicated they were overweight.

Children were identified as a target population after COPE evaluated Navajo childhood obesity by a 2013–2014 population-level study of BMI among eastern Navajo elementary school children between 3 and 6 years of age(Reference VanWassenhove-Paetzold, Rajashekara and Shin33). Using de-identified data from a health facility in eastern Navajo, 629 children were surveyed. Of the children, 51 % were male; 10 % of boys and 15 % of girls were classified as overweight (85th–94·9th BMI percentile), and 58 % of boys and 59 % of girls as obese (≥95th BMI percentile)(Reference Barlow36). As a comparison, reported trends for obesity in children aged 2–4 years (BMI > 95th percentile) suggested an overall population prevalence of 14·74 % in 2011(Reference Pan, McGuire and Blanck7).

Gaining knowledge of community assets towards a nutritional intervention (2013–2014)

Identifying community assets was a critical step towards informing diet-related intervention choices. Navajo Nation has sparse grocery stores and a low population density, with significant travel time and fuel cost involved in grocery shopping. Collaborative work with the CDC and Navajo Nation Department of Health conducted in 2013 confirmed that, while small convenience stores were more abundant than grocery stores on Navajo nation, they provided fewer options for healthy foods(Reference Kumar, Jim-Martin and Piltch37). However, while these data demonstrated the paucity of dietary fruits and vegetables available on Navajo Nation, the work served to highlight the potential of working with local stores, particularly convenience stores and trading posts, which serve as local points of contact for food sales in remote communities throughout the reservation.

Taken together, through a community-based participatory approach that focused on diet-related health problems within Navajo Nation, COPE and partners identified the key intervention populations as Navajo children and pregnant women and designed a programme to capitalise on a community desire for healthy foods in close proximity. Alongside community momentum, the strategy of partnering with small local food retailers willing to expand their healthy food options to a reliable demand was felt to be viable ground for advancing access on Navajo Nation.

Strategy 2: engaging cross-sectorial partners on intervention choice and design

Arriving at the Navajo FVRx programme (2012–2014)

Intervening upon and preventing downstream effects of diet-related health problems are most effectively accomplished through use of multi-level, multi-disciplinary approaches(Reference Fagg, Chadwick and Cole30,Reference Brown, Alwan and West31) . Successful interventions require strong community buy-in and supportive collaborators in implementation. The development of an intervention targeting healthy food access among Navajo at risk of developing diet-related health problems originated from iterative feedback received from groups with vested interest in food access, food sovereignty, food system change and diet-related health problems. This process occurred between 2012 and 2014 and involved local groups including the Diné Community Advocacy Alliance, the Diné Policy Institute, the market-access and community-involvement organisation Hasbídító, the Navajo Nation Department of Health, Navajo CHR, small store owners and local health facilities including the Indian Health Service, tribally-run facilities and other contracted providers. Partnerships or working relationships additionally included the national organisations Wholesome Wave and the CDC.

COPE and stakeholders arrived at Navajo FVRx, a programme that would equip healthcare providers with the ability to write a prescription for fruits and vegetables in the amount of one United States Dollar (USD) per d per family member, based on existing programmes in the US Families could redeem vouchers at local retailers for fresh and frozen fruits and vegetables as well as traditional Diné foods (e.g. blue and yellow maize and cornmeals, mutton/lamb, heirloom beans). This was considered an ideal strategy as a high-impact intervention that would provide families with increased purchasing power, while incorporating nutrition education and traditional dietary knowledge. Similar incentive programmes aimed at making healthy choices more affordable have been shown to be successful in other communities nation-wide(38), yet had not been implemented in a tribal community. Navajo FVRx was a response to healthcare providers’ desire to address food insecurity as part of their clinical interventions, to community and tribal advocates’ efforts to bolster the local economy on the reservation by supporting local businesses and to academic collaborators’ promotion of data-driven intervention methods.

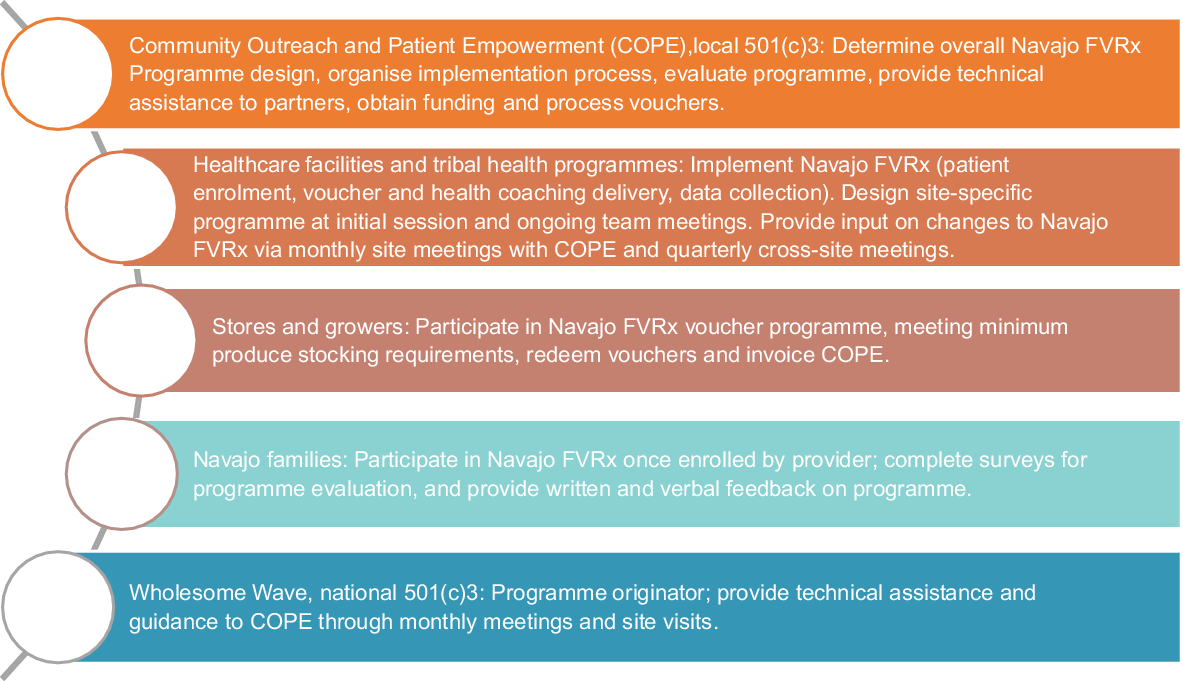

Navajo FVRx offered an avenue to build on existing resources by focusing on stores on Navajo Nation, rather than trying to create a new food system. Along with this, Navajo Nation passed the Healthy Diné Nation Act in 2014, taxing junk food while making healthy foods – including fruits and vegetables – tax exempt. Navajo FVRx helped bring tax-exempt, healthy food sale options to small businesses to support their growth away from less healthy food options. Additionally, there was potential for Navajo FVRx programmatic evaluation using existing CDC store data as a baseline. The impact not only on the health of families but also on the food environment itself could be measured through rigorous programmatic data collection. COPE’s pre-existing cross-sectorial partnerships put the organisation in a unique position to implement Navajo FVRx, with continued engagement of many stakeholders in programme implementation (Fig. 2). With the consensus to implement a voucher programme, partnerships were formed with national organisations, including Wholesome Wave, which has designed a model for FVRx programmes in the USA.

Fig. 2 Roles of key community, regional and national partners involved in the inception, design and implementation of Navajo Fruit and Vegetable Prescription (FVRx)

Through collective input from community partners, Navajo FVRx was designed to engage both health and food sectors as equally important partners in the programme. Healthcare providers from local health facilities provided the clinical point of entry for programme participants. At the same time, local vendors – including grocery stores, convenience stores, trading posts and local farmers’ markets – were recruited to redeem the vouchers. This cross-sectorial engagement was critical to creating the synergies necessary for programme success in the setting of inability to provide financial compensation to participating partners. For this reason, the programme had to be designed to ensure streamlined implementation for both healthcare providers and retailers. Furthermore, intensive support to healthcare teams, stores and growers was needed to launch the programme.

Navajo FVRx design – health sector component

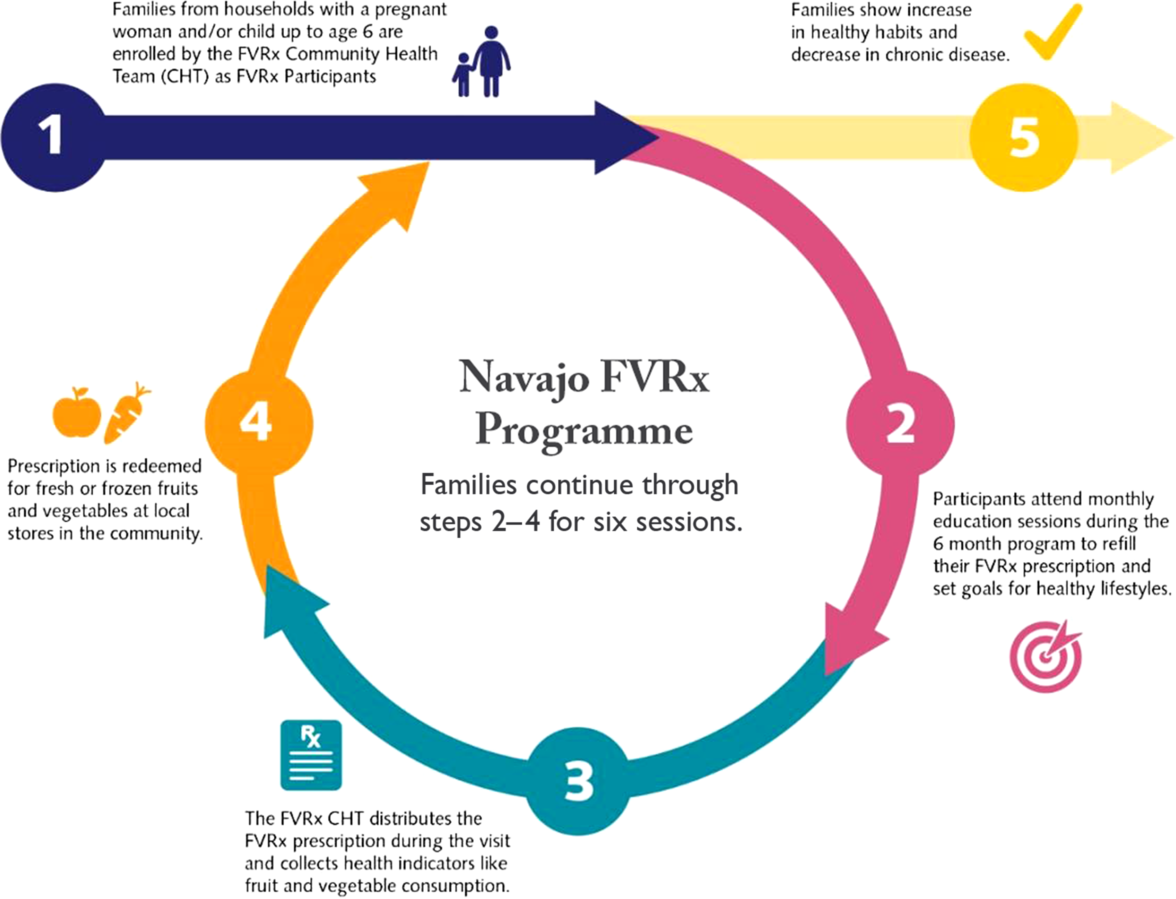

Based on community assessment data and the incorporation of prior models for fruit and vegetable voucher programmes from Wholesome Wave, Navajo FVRx was designed to provide financial and geographic access to fresh fruits and vegetables for those on Navajo Nation at risk for diet-related chronic health problems. Figure 3 displays the general programme design. At-risk individuals were identified by healthcare providers at participating Navajo FVRx sites. Initial enrolment criteria for Navajo FVRx included families with either a pregnant or post-partum mother with diabetes or a child between 3 and 6 years with a BMI percentile indicating the child was overweight or obese. Healthcare providers invited eligible participants to participate in the 6-month programme. Upon programme enrolment, families participated in monthly nutrition education sessions. At each session, group or individual programme participants were provided nutrition education. At the conclusion of the session, the adult participant or parent was provided with vouchers valued at one USD per family member, per d (capped at 4 USD/d), to last for 1 month and to be used at participating Navajo FVRx retailers. Vouchers were coupled with nutrition education in order to boost attendance and programme retention. Participants were also asked to complete a brief evaluation form at each session.

Fig. 3 Cyclical design of Navajo Fruit and Vegetable Prescription (FVRx), demonstrating the process from enrolment into the programme until completion

Navajo FVRx programme design was adapted from Wholesome Wave’s FVRx model to fit the needs identified by COPE collaborators and prior COPE studies. COPE expanded upon Wholesome Wave’s model when creating Navajo FVRx to include pregnant women in addition to overweight children and later to also include food-insecure children. Given the existing food retail infrastructure on Navajo Nation, and the findings from store product analyses at convenience stores, COPE decided to focus on small stores, a shift from Wholesome Wave’s focus on farmers’ markets, as an intervention to fundamentally improve the Navajo Nation food environment. An emphasis remained on promoting locally grown produce.

COPE developed baseline, monthly programme and exit surveys for both adult diabetes in pregnancy participants and caregivers of preschool participants. Surveys were adapted from Wholesome Wave with additional input from public health practitioners to evaluate change in pre-specified measures of food access and security; clinical outcomes; health behaviours related to fruit and vegetable consumption, physical activity, sleep and screen time, and food purchasing; as well as satisfaction with the patient–provider relationship. Clinical parameters measured with the surveys included BMI (plotted to percentiles for age and sex in children) and Hb A1c among women with diabetes in pregnancy. Related to food security, USDA-validated six-item module questions were adapted. Questions were revised to be more culturally understandable on Navajo Nation by including images, as previous work indicated that visual/symbolic representations were well received, and by modifying language to better reflect a holistic way of thinking and to match average literacy levels of community members. Before using the survey, the questions were reviewed and approved by the Navajo Nation Human Research Review Board. Surveys were further modified based on stakeholder feedback elicited from focus groups following each completed cycle of the Navajo FVRx programme.

Navajo FVRx design – food sector component

It has been demonstrated that positive health outcomes are associated with closer proximity to a supermarket(Reference Gittelsohn, Kim and He20); COPE sought to decrease the amount of travel time for families to their nearest healthy foods access point by engaging local shopping sources with Navajo FVRx (Fig. 4). COPE and partners identified retailers in FVRx site catchment areas that would have the potential to stock sufficient amounts of fruits and vegetables to supply participating families and approached store owners and corporate headquarters to engage them in FVRx. With a predictable number of families participating in Navajo FVRx, retailers were incentivised to increase their supply of fruits, vegetables and traditional Navajo foods. This improved food environment benefited not only FVRx families but also the entire community. As more stores became Navajo FVRx retailers, interest continued to expand amongst surrounding stores and stores within corporate networks. Upon evaluation of the first cycle of Navajo FVRx, COPE found that a portion of the stores struggled to stock adequate amounts of fruits and vegetables to meet families’ demand. For this reason, COPE derived a Healthy Store Index, adapted from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Minimum Stocking Levels and Marketing Strategies of Healthful Foods for Small Retail Food Stores, to easily calculate a score for each store that indicated their ability to support an increased demand for produce and traditional foods(Reference Laska and Pelletier39). COPE worked with small retailers to improve produce handling techniques, distribution channels and on-site promotion of healthy food options to increase their Healthy Food Index values and then used this Healthy Store Index threshold to identify stores that were primed to participate in Navajo FVRx for subsequent implementation cycles.

Fig. 4 Map of Navajo Nation with Fruit and Vegetable Prescription (FVRx) store and clinic sites, as of cycle III (2017). The figure displays current and future sites, as well as sites on hold during cycle III. The map was designed using Google Earth software (Google, CA, 2017)

In order to stimulate the local economy and focus on remote communities, original FVRx criteria stipulated that retailers had to be located on the Navajo reservation. Based on consultation with Wholesome Wave and local partners, vouchers could be redeemed for fruits and vegetables that were fresh or frozen without additives. Participating retailers accepted Navajo FVRx vouchers as payment for fresh and frozen fruits and vegetables, as well as some traditional food items. Stores, in turn, were asked to save their receipts documenting type of items purchased and submit them, along with the vouchers, for reimbursement by COPE.

Phase 2: implementation and iterative learning (2014-present)

Navajo FVRx community health teams

Patient-centred programme implementation was conducted by teams of community and clinic-based healthcare providers in strategic locations across Navajo Nation. These community health teams, referred to as Navajo ‘FVRx teams’, were composed of community health providers (e.g. CHR, public health nurses), clinical providers (e.g. physicians, dieticians) and public health programme employees (e.g. Head Start, Navajo Nation Special Diabetes Project). These inter-professional teams were based in clinical (e.g. clinics, hospitals) and community (e.g. Head Start classrooms, CHR office) facilities. They assumed the duties of delivering educational curriculum, the distribution of FVRx vouchers, the collection of surveys and clinical data, and the support of FVRx families and local retailers. Throughout the course of the programme, COPE facilitated an inter-professional team development curriculum for the FVRx teams, developed over multiple iterations throughout the implementation of Navajo FVRx and modified from FVRx team feedback. Aimed at improving inter-professional team efficacy across the FVRx teams, COPE developed this curriculum to help teams clarify roles and responsibilities and highlight strategies for effective communication.

Implementation cycles and programme expansion

Navajo FVRx was implemented in six-session cycles, with one session held each month. Enrolment cycles (rather than continuous enrolment) not only allowed teams to dedicate time to the programme but also pause between cycles to adjust their teams and programmes. Cycles also allowed COPE to evaluate outcomes as discrete cohorts.

Cycle I of Navajo FVRx began in 2015. Six FVRx teams, ten retailers and ten families participated in this first 6-month cycle. Cycle II began in 2016 and expanded to include nine FVRx teams and twelve retailers and served seventy-seven families for a total reach of 395 individuals. Cycle III began in 2017; to date, cycle III has involved six FVRx teams and twenty-five retailers (including two farmers’ markets). In the first implementation year (2015), retailers sold USD $10 130 of products through FVRx vouchers. In 2016, Navajo FVRx-linked sales increased nearly 500 % to a total of USD $48 771.

Programme improvement

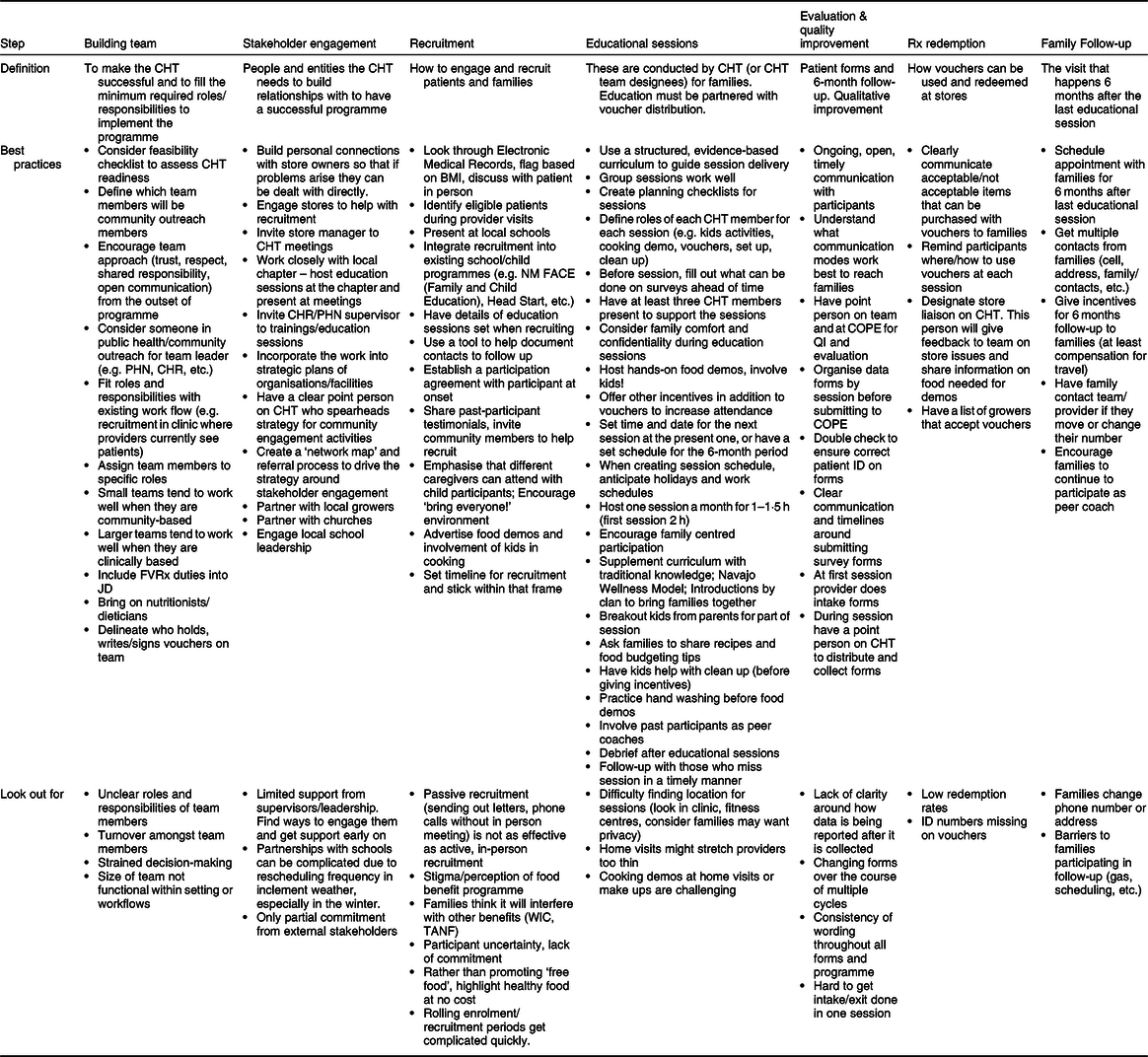

At the end of each cycle, feedback surrounding best practices and challenges was gathered from FVRx teams in one-on-one interviews, group listening sessions and ongoing meetings throughout the implementation cycle. Emphasis was also placed on learning about families’ experience with FVRx through face-to-face interviews, focus groups and surveys. Cumulative feedback from the provider teams was tracked using a best practices and challenges chart that addressed six areas of programme implementation: team building, stakeholder engagement, recruitment, education sessions, evaluation and quality improvement, prescription redemption, and family follow-up (Table 1).

Table 1 Navajo Fruit and Vegetable Prescription (FVRx) best practices and challenges*

CHT, Community Health Team; PHN, Public Health Nursing; CHR, Community Health Representative; JD, job description; TANF, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families; COPE, Community Outreach and Patient Empowerment; WIC, Women, Infants, and Children.

* Developed in conjunction with FVRx teams, based upon provider experiences operating the Navajo FVRx programme at individual sites.

After cycle I, key successes and best practices included intentional planning and programme design at each site prior to launching the programme, clear delineation of roles and responsibilities for families and providers, and alignment of FVRx duties with existing workflows for providers. Challenges involved lack of shared responsibility, communication breakdown across clinical and community healthcare providers, and structural barriers to programme participation – such as staff turnover and transportation for families or community health workers. With these findings, COPE held a series of improvement planning sessions with interdisciplinary internal and external COPE partners to streamline FVRx integration into routine clinical and community-based care and to reinforce a patient-centred approach. Additionally, edits were made to the FVRx inter-professional team development curriculum to better equip teams to define roles and responsibilities and improve communication.

Feedback after cycle II suggested these modifications resulted in improved FVRx team dynamics, as well as programme recruitment and enrolment. Suggestions for continued improvement included simplified programme tools, relaxing eligibility requirements, a wider offering of eligible products and retail locations, and less stringent FVRx team requirements. In response to this feedback, COPE, along with partner organisations, simplified the FVRx prescriptions, designed a programme toolkit to unify access to programme resources and simplified data collection forms. Eligibility requirements were expanded to include all pregnant women and children aged 0–6 years; providers were encouraged to use the Indian Health Service Food Insecurity Screening Questionnaire as a means to identify households with social risk factors rather than focus on clinical risk factors of an individual. To optimise access for families, traditional food products were included as eligible items. Stores located adjacent to reservation land were also allowed to participate if they supported regional food systems, such as purchasing from local growers and offering traditional foods. Rather than assigning families to redeem at a specific store, every participating Navajo FVRx retailer was authorised as a redemption point for every participating family. Feedback that some stores lacked adequate produce supplies led to the establishment of the aforementioned minimum produce stocking requirement as a requisite for store participation in the programme(Reference Laska and Pelletier39). Lastly, the requirements to be a FVRx team were expanded to meet the varying capacities and work flow of clinical and community-based providers.

At the beginning of cycle III, COPE convened FVRx teams to gather feedback on these updates. The FVRx teams were receptive to the changes and provided added suggestions for improvement including to further expand eligibility, to increase the number of local growers as redemption sites and to continue to strategise around aligning duties with workflow for providers. COPE made determinations on overarching programme elements based on collective feedback, resulting in the modifications to Navajo FVRx described in Table 2. However, many decisions were left to team discretion, allowing for heterogeneity across sites. For example, several FVRx teams raised the issue of whether families could be re-enrolled after completing a cycle. COPE encouraged sites to determine their own policies regarding how to allocate resources. While most sites opted against re-enrolment in order to expand access to new families, several sites allowed re-enrolment particularly among families with severe food insecurity.

Table 2 Core programme elements of Navajo Fruit and Vegetable Prescription (FVRx)*

* Currency is in United States Dollar ($).

Discussion

COPE’s community-based participatory approach to building Navajo FVRx has allowed for broad community-driven and culturally relevant design of the programme. Continued community involvement has preserved an iterative approach throughout programme implementation that focuses on the local context and its changing needs. With a socio-ecologically informed understanding of the needs and assets of Navajo families, COPE has been able to incorporate programmatic elements identified as important by multiple stakeholders and move towards transformation of the food environment and improved health among those at risk for diet-related health problems on Navajo Nation.

COPE and partners have strived to create a programme guided by three core principles: the overarching goal of reducing diet-related health disparities; a patient-centred approach and site-based flexibility and ownership. By reinforcing patient centredness as a core principle, teams are able to make their own decisions when designing their version of the programme. For instance, while families must have a pregnant person and/or child aged 0–6 years, teams can decide whether to narrow their target population using additional eligibility criteria (e.g. diabetes in pregnancy, obesity, food insecurity). Navajo FVRx must include health coaching to families, but again, teams may choose whether to use a structured curriculum and if so, whether to deliver one-on-one or in groups. With each phase of improvement, COPE has been careful to communicate to teams regarding changes and to maintain ongoing, close communication through different venues to clarify questions as they arise.

In future Navajo FVRx cycles, COPE will continue to restructure the programme based on feedback from families and providers. In addition, data collected from each cycle of the programme will be important to understand the effects of the programme on improving access to healthy foods, changes in food security, health and nutritional literacy, reduction of barriers to achieving healthy diets and changes in health indicators for vulnerable Navajo populations. Additionally, such forthcoming data will provide insight into the limitations of this programme as it compares with other multi-sectorial diet-related health problem interventions occurring in comparable populations.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: Please note that authors M.A.S. and A.C.W. contributed equally to this work and share authorship position. We acknowledge the many important contributions from multiple clinic sites and providers, non-profit programmes, tribal programmes, governmental agencies and participants in the development of Navajo FVRx. Financial support: Funding (in part) was by the Notah Begay III Foundation (NB3F) through the Walmart Foundation, the Rx Foundation, the Zegar Family Foundation and the Leonard Family Foundation. Funding was made possible (in part) by a cooperative agreement with the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (no. 5NU58DP005872). This project was supported (in part) by the University of Minnesota General Internal Medicine Research Fund. Conflict of interest: The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the official views of the Indian Health Service or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does the mention of trade names, commercial practices or organisations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Authorship: M.A.S.: formulation of study design, analysis of data and writing of article. A.C.W.: formulation of study design, carrying out study and writing of article. J.V.P., C.G., S.M.S. and G.G.: formulation of study design, carrying out study and analysis of data. D.S.C., L.J.B., A.M., B.J., K.B.C., M.G.B., T.W., H.S.S., O.M., L.H., M.T., C.K.B., E.E., J.M., J.P. and A.F.: formulation of study design and carrying out study. S.S.S.: formulation of study design, carrying out study, analysis of data and writing of article. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving human subjects/patients were approved by the Navajo Nation Human Research Review Board. Verbal informed consent was obtained prior to enrolment of participants in the programme.