Introduction

The Argentine shortfin squid Illex argentinus Castellanos, 1960 (Ommastrephidae) is a neritic-oceanic species, widely distributed along the outer shelf and slope of the south-western Atlantic Ocean, between 22°S and 54°S (Brunetti, Reference Brunetti1988; Torres Alberto et al., Reference Torres Alberto, Bodnariuk, Ivanovic, Saraceno and Acha2020), however, most catches occur in the southern range of the species (35°S to 52°S) (Haimovici and Pérez, Reference Haimovici and Pérez1990; Haimovici et al., Reference Haimovici, Brunetti, Rodhouse, Csirke, Leta, Rodhouse, Dawe and O'Dor1998, Reference Haimovici, Aguiar dos Santos, Bainy, Gomes Fischer and Cardoso2014). Two main currents (Malvinas and Brazil currents) dominate the regional oceanography, with their variability and interactions with other masses of water being the main determining factors of the Argentine shortfin squid distribution (Nigmatullin, Reference Nigmatullin1989; Haimovici et al., Reference Haimovici, Brunetti, Rodhouse, Csirke, Leta, Rodhouse, Dawe and O'Dor1998; Bazzino and Quiñones, Reference Bazzino and Quiñones1999). Such temporal variations in environmental conditions are common processes in the region, resulting in changes in the abundance and availability of squid preys, which, in turn, explain the interannual fluctuations usually recorded in squid abundance (Bazzino and Quiñones, Reference Bazzino and Quiñones1999). Furthermore, for I. argentinus, as for many other squid species, these strong interannual fluctuations in abundance are also a consequence of its semelparous life strategy and its latitudinal and bathymetric migrations, coupled with environmental influences on its recruitment (Dawe and Brodziak, Reference Dawe, Brodziak, Rodhouse, Dawe and O’ Dor1998; Pierce et al., Reference Pierce, Valavanis, Guerra, Jereb, Orsi-Relini, Bellido, Katara, Piatkowski, Pereira, Balguerias, Sobrino, Lefkaditou, Wang, Santurtun, Boyle, Hastie, MacLeod, Smith, Viana, González and Zuur2008; Torres Alberto et al., Reference Torres Alberto, Bodnariuk, Ivanovic, Saraceno and Acha2020).

Illex argentinus is a short-lived species, displaying a rapid growth rate and an annual life cycle, resulting in non-overlapping generations. It exhibits opportunistic trophic strategies, displaying a highly dynamic role in the trophic web, which can shift significantly between years and geographical areas due to variations in recruitment and in the abundance of interacting species within the food chain (Dawe and Brodziak, Reference Dawe, Brodziak, Rodhouse, Dawe and O’ Dor1998).

This is one of the most important commercial squid species for the Argentine fisheries, with total catches reaching 345 000 tons in 2020 (FAO, 2022). The assessment of their stocks is, therefore, critical for a sustainable fishing exploitation, but also for the maintenance of the ecological integrity of food webs given the relevance of the squids as both predator and prey (Vidal and Haimovici, Reference Vidal and Haimovici1999). The population structure of the southern range of I. argentinus is complex, with 4 stocks or subpopulations being differentiated according to the season and reproduction ground (Fig. 1): the spring-spawning stock (SpSS), the bonaerensis-north patagonic stock (BNPS), the summer-spawning stock (SSS) and the south patagonic stock (SPS) (Brunetti, Reference Brunetti1988; Ivanovic et al., Reference Ivanovic, Elena, Rossi and Buono2016; Arkhipkin et al., Reference Arkhipkin, Nigmatullin, Parkyn, Winter and Csirke2023). During the austral summer, from December to February, densest concentrations of I. argentinus, composed by juveniles and adults of 2 stocks (SPS and SSS, respectively), occur over the Patagonian continental shelf between 43°S and 55°S (Brunetti et al., Reference Brunetti, Elena, Rossi, Ivanovic, Aubone, Guerrero and Benavides1998). The co-occurrence in this zone, at certain times of the year, takes place due to the migratory-reproductive annual cycle of SPS, determining a mixing zone between 47°S and 49°S, approximately (Avigliano et al., Reference Avigliano, Ivanovic, Prandoni, Méndez, Pisonero and Volpedo2020). Stocks are distinguishable from each other by their size and their gonadal maturity. Indeed, reproductive squids, corresponding to SSS specimens, are found in the north region (44°–48°S), whereas pre-reproductive concentrations between 49°–52°S are represented by SPS individuals (Ivanovic et al., Reference Ivanovic, Elena, Rossi and Buono2016). Furthermore, a comprehensive stock assessment is necessary because this species is exploited during its ontogenetic migrations, both within exclusive economic zones of different coastal states along South American coasts and in adjacent high seas (Arkhipkin et al., Reference Arkhipkin, Nigmatullin, Parkyn, Winter and Csirke2023). In the high seas, where squids harvest accounts for around 45% of the total catch, regulation and control of fisheries are non-existent, posing a serious risk of stock depletion becoming the resource highly vulnerable to overfishing during years of poor recruitment and low abundance (Arkhipkin et al., Reference Arkhipkin, Nigmatullin, Parkyn, Winter and Csirke2023), highlighting the need for their precise identification.

Figure 1. Study area showing the stocks distribution of Illex argentinus, spring-spawning stock (SpSS); bonaerensis-north patagonic stock (BNPS); summer-spawning stock (SSS); south patagonic stock (SPS). Coh19: cohort 2019; Coh20-1, Coh20-2: cohort 2020; Coh21: cohort 2021. Inverted triangles and squares represent a single station of Coh19 and Coh20-2 samples, respectively; whereas triangles and rhombuses belong to 5 and 2 stations of Coh20-1 and Coh21, respectively.

According to Timi and Buchmann (Reference Timi and Buchmann2023), the vast majority of studies on parasites as biological indicators to discriminate stocks deal with teleost fish as host, with a comparatively lower number of studies considering elasmobranchs and invertebrates. Despite the economic relevance of I. argentinus for regional fisheries and the knowledge about their parasites (Threlfall, Reference Threlfall1970; Nigmatullin, Reference Nigmatullin1989; Hochberg, Reference Hochberg and Kinne1990; Nigmatullin and Shukhgálter, Reference Nigmatullin and Shukhgálter1990; Sardella et al., Reference Sardella, Roldán and Tanzola1990; Vidal and Haimovici, Reference Vidal and Haimovici1999; González and Kroeck, Reference González and Kroeck2000; Cipriani et al., Reference Cipriani, Giulietti, Palomba, Mattiucci, Bao and Levsen2019), a single study has used parasites as indicators for their stock assessment in San Matías Gulf, Argentina (González and Kroeck, Reference González and Kroeck2000). However, results on parasite tags should be taken cautiously, and must consider the lifespan of squid parasites and its interaction with host characteristics, especially when infestations depend on host size or age (Lester and MacKenzie, Reference Lester and MacKenzie2009; Timi and Poulin, Reference Timi and Poulin2020). Indeed, the ecology and behaviour of cephalopods, together with life cycle, mantle size, deep range and vagility are important drivers of parasite diversity (González et al., Reference González, Pascual, Gestal, Abollo and Guerra2003). Additionally, migratory species such as squids, which alternate between feeding and spawning habitats, can evidence ontogenetic changes in the structure of transient parasite assemblages, leading to misinterpretation of their stock structure.

In this paper, the variability of parasite loads due to hosts and environment is analysed for squids of the SSS stock because it is known that they perform only small-scale spatial migrations, restricted to the outer shelf at depths ranging between 50 and 200 m, not using high sea areas every year (Arkhipkin et al., Reference Arkhipkin, Nigmatullin, Parkyn, Winter and Csirke2023). This characteristic makes the SSS easier to analyse than the SPS stock, which undergoes extensive migrations and, as a result, introduces potential variability to parasite loads when moving through oceanographically distinct areas. The aim of this study is, therefore, to analyse the inter- and intra-cohort variability in the structure of parasite assemblages in the SSS of I. argentinus to assess their value as indicators of stock structure in further studies at broader scales.

Materials and methods

Squid and parasites sampling

A total of 318 specimens of I. argentinus, distributed in 4 samples, corresponding to 3 consecutive cohorts (Coh19, Coh20-1, Coh20-2, Coh21) of the SSS caught between 2020 and 2022, were examined for metazoan parasites (Table 1). Two of them, Coh20-1 and Coh21, were obtained from research cruises of the Instituto Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo Pesquero (INIDEP), and those corresponding to Coh19 and Coh20-2 were obtained from commercial catches during summer, at intermediate waters of central Patagonia. Squids belonging to Coh20-1 and Coh21 included 5 and 2 stations, respectively, whereas Coh19 and Coh20-2 both included a single station (Fig. 1).

Table 1. Composition of 4 samples of Illex argentinus belonging to 3 consecutive cohorts of summer-spawning stock

Squids were deep frozen in plastic bags at −18°C until the examination. After thawing, each squid was measured (dorsal mantle length [ML], cm) and cut along the ventral midline of the mantle. Furthermore, sex and gonadal maturity index according to an established scale of maturity (Brunetti et al., Reference Brunetti, Ivanovic and Sakai1999) were determined.

The mantle, funnel, buccal cavity and viscera (oesophagus, stomach, digestive caecum, intestine, digestive gland, gills, heart, kidney and gonads) were examined and parasites were recovered and examined under a stereoscopic microscope. Some specimens were fixed on formalin 4% and ethanol 96% for morphological and molecular identification, respectively.

Genetic identification of cestode larvae

Given the wide range of sizes and shapes of larval cestodes (plerocercoids) parasitizing I. argentinus (see Threlfall, Reference Threlfall1970; Nigmatullin and Shukhgálter, Reference Nigmatullin and Shukhgálter1990), and the presence of intermediate forms and sizes, it was necessary to assess how many taxa they represent. Therefore, a subsample of 8 plerocercoids from digestive tracts and 1 undeveloped larva found encysted in the stomach wall were collected for genetic analysis. DNA extraction was carried out using whole specimens with the DNeasy Blood and Tissue® Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. A fragment (~1400 bp) of the lsrDNA gene (28S rDNA) spanning domains D1–D3 was amplified using the primer combinations ZX-1 (Waeschenbach et al., Reference Waeschenbach, Webster, Bray and Littlewood2007)/1500R (Tkach et al., Reference Tkach, Littlewood, Olson, Kinsella and Swiderski2003) or LSU5 (Littlewood et al., Reference Littlewood, Curini-Galletti and Herniou2000)/1200R (Lockyer et al., Reference Lockyer, Olson and Littlewood2003). The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) reactions were carried out in a 25 μL volume containing 0.5 μL of each primer (10 mm), 3 μL of MgCl2 25 mm (Promega, Wisconsin, USA), 5 μL of 5 × buffer (Promega), 2 μL of dNTPs 10 mm, 0.25 μL of Go-Taq Polymerase (5 U μL−1) (Promega), 5 μL of total DNA (~30 ng μL−1) and sterilized distilled water up to 25 μL. PCR temperature conditions were the following: 94°C for 2 min (initial denaturation), followed by 40 cycles at 94°C for 30 s (denaturation), 56°C for 45 s (annealing), 72°C for 2 min (extension) and followed by post-amplification at 72°C for 7 min.

All amplified PCR products were verified in a 1.2% agarose gel. The successful PCR products were purified using QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit or QIAquick PCR purification Kit (Qiagen). Sequencing of both strands was carried out using ABI 3730XLs automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Macrogen, South Korea).

Sequences were edited and assembled in Proseq v.3.5 (Filatov, Reference Filatov2002) and deposited in the GenBank database. For identification, generated sequences were compared against the NCBI database using the BLAST algorithm (Sayers et al., Reference Sayers, Bolton, Brister, Canese, Chan, Comeau, Connor, Funk, Kelly, Kim, Madej, Marchler-Bauer, Lanczycki, Lathrop, Lu, Thibaud-Nissen, Murphy, Phan, Skripchenko, Tse, Wang, Williams, Trawick, Pruitt and Sherry2022). Sequences are available from GenBank under accession numbers OR725126 to OR725133.

Quantitative and similarity analysis of parasites

Each parasite was identified and counted and the prevalence and mean abundance for each species in each sample were calculated following Bush et al. (Reference Bush, Lafferty, Lotz and Shostak1997). The ML was compared across samples by a 1-way permutational multivariate analysis of the variance (PERMANOVA, Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Gorley and Clarke2008) on Euclidean distances (1 × 4 factorial design, ‘sample’ as fixed factor), testing for main effects after 9999 permutations and subsequent post-hoc pairwise comparisons. Following Anderson et al. (Reference Anderson, Gorley and Clarke2008), an unrestricted permutation of raw data was used as the method of permutation. Species richness (S) was calculated for each individual squid, and the mean values were compared across samples by a PERMANOVA analysis as in the case of ML, but applying a sequential sum of squares (type I SS) because samples were unbalanced (different numbers of squids examined by sample) and host size was included as a covariate (analysis of covariance [ANCOVA] model).

Multivariate analyses between samples were conducted using both Bray–Curtis index (based on abundances) and Jaccard index (based on presence/absence) for all possible pairs of hosts (infracommunities sensu Bush et al., Reference Bush, Lafferty, Lotz and Shostak1997) from different samples. Due to the large differences in parasite loads across parasite species, data were square root-transformed prior to all analyses in order to downweigh the importance of most prevalent/abundant species, so that the less dominant species contribute in determining similarity among samples (Clarke and Gorley, Reference Clarke and Gorley2015).

To evaluate if samples can be differentiated based on the abundance and composition of their parasite assemblages, non-metric multidimensional scaling (nMDS) of the both similarity matrices was performed between all infracommunities, and their centroid differences were visualized by means of bootstrap averaging based on repeated resampling (with replacement, 75 iterations) from the original dataset (Clarke and Gorley, Reference Clarke and Gorley2015). Differences between infracommunities among samples were further examined using canonical analysis of principal coordinates (CAP) (Anderson and Willis, Reference Anderson and Willis2003; Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Gorley and Clarke2008).

The structures of parasite infracommunities were compared between samples considering possible gender difference, introducing host ML as a covariable (ANCOVA model, 2 × 4 factorial design, samples and sex as fixed factors) and testing for main effects after 9999 permutations, using Bray–Curtis and Jaccard indices. Following Anderson et al. (Reference Anderson, Gorley and Clarke2008), a permutation of residuals under a reduced model was used as the method of permutation. A sequential sum of squares (type I SS) was applied because the use of a covariate due to samples was unbalanced (different numbers of squids examined by sample). Where differences were detected by PERMANOVA, pairwise comparisons were used to determine which samples differed. All similarity and distance measures, as well as multivariate analyses were implemented in PRIMER V7 and PERMANOVA+ for PRIMER package (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Gorley and Clarke2008).

Results

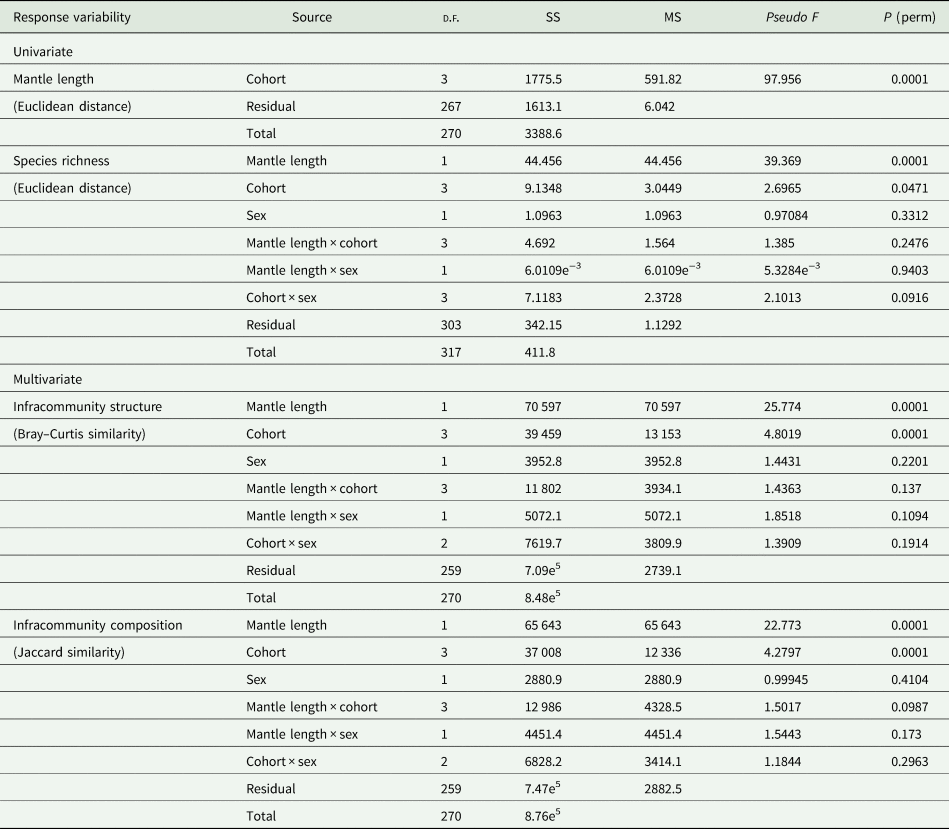

Squid ML was significantly different among samples (F 7,246: 97.956; P perm < 0.01) (Table 2, Fig. 2A), with pairwise comparisons showing significant differences (P perm < 0.01) for most pairs of samples, except between Coh19 and Coh21 (P perm > 0.05).

Table 2. PERMANOVA results of comparisons of mantle length, species richness, composition and structure of parasite communities of Illex argentinus across 4 samples corresponding to 3 cohorts of the summer-spawning stock

P values obtained after 9999 permutations.

Figure 2. Averaged dorsal mantle length (A) and infracommunity species richness (B) of Illex argentinus in 4 samples of the summer-spawning stock. Cohorts are represented by a grey scale. Vertical bars representing standard deviations (as shown in Table 2). Coh19: cohort 2019; Coh20-1, Coh20-2: cohort 2020; Coh21: cohort 2021.

The molecular characterization allowed to identify 7 of the phyllobothriid plerocercoid sequences (1201 bp) as belonging to Clistobothrium n. sp. 1 (MT732134) and Clistobothrium sp. (KM272992 and MT732134) deposited in GenBank, with a percentage of identity of 99.67 (1 isolate) to 100% (6 isolates). Therefore, all morphological types of phyllobothriid plerocercoids were pooled for further analyses. The sequence of the undeveloped larval cestode (1430 bp) retrieved a percentage of identity of 96.65–96.79% with sequences of 3 unidentified species of Grillotia (Lacistorhynchidae) (MH688700, MH688704 and MH688707).

The whole sample of I. argentinus harboured 12 parasite taxa (Table 3). At infracommunity level, no differences in species richness were observed across samples (Table 2, Fig. 2B). A total of 85.22% squids were parasitized by at least 1 species, and 2187 individual parasites were recorded in the whole sample (Table 3). Only 8 of those taxa showed a prevalence >10% in at least 1 of the samples. Most parasites were larval forms, with the exception of the digeneans Derogenes varicus and Elytrophalloides oatesi, and the nematode Hysterothylacium aduncum, all found in the digestive tract. Larval cestodes dominated numerically the assemblages, representing 64.84% of individual parasites, being mainly represented by phyllobothridians and tetraphyllidians found in the digestive caecum, and less commonly in gills, stomach, intestine, funnel, buccal cavity and oesophagus.

Table 3. Prevalence (P), mean abundance (MA) with standard deviation (s.d.), site of infection and stage of development of parasites of Illex argentinus in 4 samples corresponding to 3 consecutive cohorts of the summer-spawning stock

Di, digestive tract; Ma, mantle cavity; Co, coelomic membrane; St, stomach wall.

a Genetic identification.

The bootstrap-average-based nMDS ordination of both Bray-Curtis (Fig. 3A) and Jaccard (Fig. 3B) was similar to each other, and showed an apparent pattern of separation between samples, with a low level of stress (0.04 and 0.05, respectively). Squids from Coh21 were clearly separated from the rest, especially along the first axis; parasite assemblages of Coh19 occupied an intermediate position between the 2 samples of Coh20, these 3 groups being mainly separated along the second axis.

Figure 3. Non-metric multi-dimensional scaling plot (nMDS) of bootstrap averages (75 repetitions) of parasite infracommunities of Illex argentinus distributed within 4 samples at intermediate waters of central Patagonia based on Bray–Curtis and Jaccard similarity of square root-transformed data. Individual repetitions are based on random draw and replacement of samples from the original dataset. Black symbols represent the overall centroids across all repetitions. Grey areas represent 95% confidence regions. Coh19: cohort 2019; Coh20-1, Coh20-2: cohort 2020; Coh21: cohort 2021.

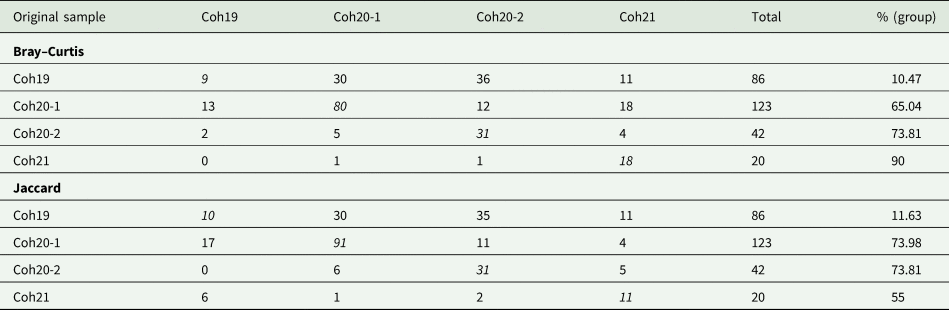

The CAP analysis showed significant differences among samples (tr = 0.4725 and tr = 0.558 for Bray–Curtis and Jaccard, respectively; both P < 0.001). The selected orthonormal PCO axes (m = 5 and m = 6, respectively) described 92.5 and 99.15%, respectively, of the variation in the data ‘cloud’, although the percentage of correct allocations was relatively low (50.9 and 52.8%, respectively). Cross-validation results based on Bray–Curtis similarity (Table 4) showed that Coh21 had the highest percentage of correctly allocated squids, whereas most hosts from both samples of Coh20 were mostly allocated to their respective sample. Finally, Coh19 showed a very low proportion of correctly allocated squids, most of which were misclassified among Coh20-1 and Coh-20-2. When Jaccard index was considered (Table 4), a similar picture was observed, although several squids of Coh21 were misclassified in Coh19.

Table 4. Results of the cross-validation of principal co-ordinates analysis (CAP) based on Bray–Curtis and Jaccard similarity (leave-one-out allocation of individual squid to 1 of 4 samples)

Rows correspond to group memberships, including the percentage of correctly classified squid to their individual sample. Numbers in italics indicate number of squids in 4 samples of spawning-summer stock correctly allocated to their own locality.

The structure and composition of parasite infracommunities varied across samples and with ML but not with host sex, nevertheless no interaction between ML and samples was observed (Table 2). Pairwise comparisons after ‘correcting’ for the effect of squid length evidenced significant differences for both Bray–Curtis and Jaccard indices among most pairs of samples (Pperm < 0.01), whereas squids from Coh19 were similar to those of both Coh20-1 and Coh20-2 (Pperm > 0.05).

Discussion

Previous records of parasites in I. argentinus from the south-western Atlantic Ocean are mostly descriptive, and include several species of cestodes, digeneans, nematodes, 1 copepod and 1 coccidia (Threlfall, Reference Threlfall1970; Nigmatullin, Reference Nigmatullin1989; Hochberg, Reference Hochberg and Kinne1990; Nigmatullin and Shukhgálter, Reference Nigmatullin and Shukhgálter1990; Sardella et al., Reference Sardella, Roldán and Tanzola1990; Vidal and Haimovici, Reference Vidal and Haimovici1999; González and Kroeck, Reference González and Kroeck2000; Cipriani et al., Reference Cipriani, Giulietti, Palomba, Mattiucci, Bao and Levsen2019). To our knowledge, the present findings represent new host records for the digenean E. oatesi, the cestode Lacistorhynchidae gen. sp., larval nematodes of the Order Rhabditida and the gnathiid isopod.

In agreement with previous studies on parasite fauna of other cephalopod species (Pascual et al., Reference Pascual, González, Arias and Guerra1995; Brickle et al., Reference Brickle, Olson, Littlewood, Bishop and Arkhipkin2001; Tedesco et al., Reference Tedesco, Bevilacqua, Fiorito and Terlizzi2020), cestode plerocercoids were the most abundant group found in I. argentinus, which also showed a substantial morphological variability (see Threlfall, Reference Threlfall1970; Nigmatullin and Shukhgálter, Reference Nigmatullin and Shukhgálter1990; Sardella et al., Reference Sardella, Roldán and Tanzola1990). Characterization of species via molecular analysis allowed to confirm that the larvae of Phyllobothrium sp., previously reported in I. argentinus, correspond to the phyllobothridean genus Clistobothrium, as was shown by Brickle et al. (Reference Brickle, Olson, Littlewood, Bishop and Arkhipkin2001) for cestodes from Doryteuthis gahi caught in southern areas. Similarly, the larval morphotype previously identified as Pelichnibothrium speciosum (Threlfall, Reference Threlfall1970; Nigmatullin and Shukhgálter, Reference Nigmatullin and Shukhgálter1990; Sardella et al., Reference Sardella, Roldán and Tanzola1990) was genetically identified as Clitobothrium. The incipient development of the larvae that was found to be encysted did not allow their identification as a trypanorhynch cestode due to the lack of structures such as tentacles or bothridia. The absence of these structures has been observed in early stages of the larval development in some trypanorhynchs, such as those of the genus Grillotia (Schramm, Reference Schramm1991). Indeed, the highest percentages of identity were concordant with sequences of 3 unidentified species of Grillotia found in Amblyraja radiata, Bathyraja magellanica and B. brachyurops, respectively, the last 2 from South Atlantic Ocean (Beer et al., Reference Beer, Ingram and Randhawa2019).

Many studies on parasites of cephalopods are aged and reliant upon morphological features. Only recently, the implementation of molecular techniques began to more accurately elucidate the taxonomic status of cestode species parasitizing squids (Brickle et al., Reference Brickle, Olson, Littlewood, Bishop and Arkhipkin2001; Caira et al., Reference Caira, Jensen, Pickering, Ruhnke and Gallagher2020; Guardone et al., Reference Guardone, Giusti, Bilska-Zajac, Malandra, Różycki and Armani2020), providing evidence of a potential overestimation of cestode species in I. argentinus and allowing proper comparisons for squid stock assessment.

Host size is an important feature that affects parasite diversity by influencing the rates of colonization by new parasites (Luque and Poulin, Reference Luque and Poulin2004). Furthermore, host size is a useful surrogate of trophic level, determining patterns of predation and vulnerability to mortality (Jennings et al., Reference Jennings, Pinnegar, Polunin and Boon2001). Consequently, the characterization of the relationship between fish size and diet and trophic level is essential for assessing how much these interactions affect the structure of parasite assemblages (Timi et al., Reference Timi, Luque and Poulin2010, Reference Timi, Rossin, Alarcos, Braicovich, Cantatore and Lanfranchi2011). In the present study, whereas the increase of ML in Coh20-2 regarding Coh20-1 is an expected result, since the 2 months separating samples represent a considerable proportion of the annual squid lifespan, the observed variability in ML across years, even when squids were caught in the same month, can be attributed to the fact that growth and recruitment of cephalopods are highly influenced by environmental conditions. This results in wide inter-annual fluctuations of these processes, and even a sub-structure of microcohorts (intra-annual) is frequently present (Boyle and Rodhouse, Reference Boyle and Rodhouse2005). Regarding parasites, the mean infracommunity species richness was uniform across samples. Such homogeneity responds to the small number of species found in the whole sample and the recurrence in the dominance by the same group of species, independently of their variability in abundance across samples. In the region, the diet of squids has evidenced a very low diversity and the dominance of a single type of prey in the majority of stomachs so far examined (Ivanovic and Brunetti, Reference Ivanovic and Brunetti1994; Ivanovic, Reference Ivanovic2010; Prandoni, Reference Prandoni2022). Considering that most parasites of I. argentinus are acquired through the consumption of parasitized preys, the low diversity in its food items explain the rather homogeneous species richness recorded.

Beyond the similar values of species richness, all multivariate analyses evidenced a high level of structural and compositional heterogeneity across samples, largely driven by differences in squid size, but not by sex. Given that most parasites are transmitted trophically to squids, changes in parasitism are surely determined by host diet and its ontogenetic and seasonal changes. Transient parasites, namely those living in the gut lumen of hosts, such as most helminths found in I. argentinus, can persist in the host for a few weeks (Lester et al., Reference Lester, Barnes and Habib1985; Lester, Reference Lester1990) representing mostly the food items consumed in recent times, whereas long-lived parasites, such as larvae of Anisakis, tend to accumulate as the host ages (Braicovich et al., Reference Braicovich, Ieno, Sáez, Despos and Timi2016). This cumulative pattern is readily evident when comparing the increase of prevalence in squids from the same cohort, caught 2 months later.

The dominance of short-lived helminths makes the parasite assemblages of the Argentine shortfin squid highly susceptible to short-term environmental fluctuations, either directly or indirectly through their effect on zooplankton and other intermediate hosts. Consequently, depending on recent diets, their composition and structure can vary accordingly, driving unpredictable temporal patterns. Indeed, the observed interannual changes were not uniform, with parasite communities of Coh19 and Coh20 being more similar to each other than to Coh21. Similar heterogeneities were observed even for members of the same cohort. Of course, these differences are influenced by the differences in squid size and the locality of capture, but even after correcting for host size, most differences remained. On the other hand, squid sex had no effect on parasite loads. This is a consequence of the numerical preponderance of trophically transmitted parasites in a host that does not exhibit gender differences in diet composition or relative abundance (Prandoni, Reference Prandoni2022), nor in somatic growth rates prior to sexual maturity (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Chen, Chen and Fan2015). Likewise, no differences between sexes were observed for the parasites of Illex coindetii in Galician waters, Spain (Pascual et al., Reference Pascual, González, Arias and Guerra1995).

In addition to the features of the parasite taxa, as well as of the host diet and its variations, other host and environmental characteristics play crucial roles in determining the observed patterns of parasite variability. Indeed, I. argentinus, like many other cephalopods, exhibits high metabolic rates and rapid growth, whose high variability is environmentally driven, resulting in interannual variations in stock abundance and distribution (Arkhipkin et al., Reference Arkhipkin, Hendrickson, Payá, Pierce, Roa-Ureta, Robin and Winter2021). Furthermore, its life cycle is highly variable both spatially and temporally due to their latitudinal migrations and bathymetric distribution, the latter also changing throughout its ontogeny (Ivanovic et al., Reference Ivanovic, Elena, Rossi and Buono2016), all features that make their trophic interaction quite dynamic and scale-dependent.

In relation to the environment, spawning of I. argentinus is associated with marine fronts, whose characteristics change seasonally and their geographical locations vary according to the dynamics of marine currents in semi-annual, annual and biannual cyclic periods (Acha et al., Reference Acha, Mianzan, Guerrero, Favero and Bava2004; Sacau et al., Reference Sacau, Pierce, Wang, Arkhipkin, Portela, Brickle, Santos, Zuur and Cardoso2005). Indeed, studies modelling squid abundance in this ecosystem have retained sea surface temperature, latitude, longitude, month, average fishing depth and year as main predictors (Sacau et al., Reference Sacau, Pierce, Wang, Arkhipkin, Portela, Brickle, Santos, Zuur and Cardoso2005), evidencing the complexity of the system and justifying its variability. Disparate environmental conditions, when experienced by early stages of I. argentinus, can also affect the success of recruitment (Torres Alberto et al., Reference Torres Alberto, Bodnariuk, Ivanovic, Saraceno and Acha2020) and growth rates (Arkhipkin, Reference Arkhipkin1990; Haimovici et al., Reference Haimovici, Brunetti, Rodhouse, Csirke, Leta, Rodhouse, Dawe and O'Dor1998), leading to interannual differences in growth either intracohort and between winter stocks (Arkhipkin and Scherbich, Reference Arkhipkin and Scherbich1991; Haimovici et al., Reference Haimovici, Brunetti, Rodhouse, Csirke, Leta, Rodhouse, Dawe and O'Dor1998).

All these sources of variability related to parasites, hosts and environment are expected to be reflected on parasite assemblages of I. argentinus, requiring consequently a careful selection of those parasite tags to be used or, at least, to make cautious interpretations of the observed patterns. In view of this generalized variability, stock differences can be overestimated, undermining its value as management tools for sustainability of the resource. For such purposes, and to promote a rational exploitation of squids, differences between stocks of I. argentinus using parasite tags should be based on specimens of equivalent size or age, and caught simultaneously at the putative stock units under study. Any departure of these conditions poses a serious risk of misinterpreting natural variability due to the stock of origin. This seems to be the case of the previous study on parasite tags for I. argentinus (González and Kroeck, Reference González and Kroeck2000), where differences in parasite fauna were attributed to variations between stocks arriving with months of differences to a north patagonian gulf and showing notable differences in ML. Even when the stock identification based on squid size and maturity could be correct, the variability in parasite loads may respond to different causes, such as to squid size and not to the stock of origin. Indeed, higher species richness and abundances were observed in a sample composed by squids ranging between 23 and 38 cm ML, in relation to the second sample whose members measured between 14 and 22 cm ML. Although a gradual increase of parasitism is acknowledged (González and Kroeck, Reference González and Kroeck2000), host size seems to be overlooked as a relevant determinant of these changes. Furthermore, the authors argue that these stocks are biotopically isolated from those inhabiting neighbouring areas when compared with previous studies carried out a decade earlier.

The biological and ecological host features regulating the prevalence and abundance in parasite assemblages, mostly composed of transient parasites, are shared by many squid species. Research on parasites as tags has been misleading as an ad hoc tool in elucidating the discreteness of unit stocks (Pascual and Hochberg, Reference Pascual and Hochberg1996). Few previous works using parasites as indicators of stock structure for squids have been carried out worldwide, being not free of these flaws, or having concluded that parasites are of little value as biological tags. For example, Dawe et al. (Reference Dawe, Mercer and Threlfall1982) analysed the parasites of the short-finned squid Illex illecebrosus of several sizes caught at several localities, seasons and years in the northwest Atlantic. The authors concluded that, because of the broad geographic distribution of parasites, their condition of generalists and the lack of taxonomic resolution, parasites were useless as indicators. On the other hand, Bower and Margolis (Reference Bower and Margolis1991) proposed parasites of the flying squid, Ommastrephes bartrami, as potential tags for discriminating stocks between north-western and north-eastern Pacific waters based on differences, after comparing their results with previous studies carried out years earlier and not considering squid size or age as relevant variables. Pascual et al. (Reference Pascual, González, Arias and Guerra1995) conducted a survey of parasites of short-finned squid I. coindetii taken from 2 locations off the north-western Iberian Peninsula. Despite finding geographic differences, parasite infections showed close correlations with host life-cycle, with parasite loads increasing often with host size and maturity, which were considered for interpreting the observed patterns. In a multidisciplinary study of Nototodarus sloani from New Zealand waters, carried out by Smith et al. (Reference Smith, Roberts and Hurst1981), parasitological evidence, after taking account of host age (or length) and month of capture, supported the results of genetic and morphological study resulted in the identification of 2 congeneric host species.

Owing to the short life-cycles and variable growth rates of most cephalopods, their stocks may be highly volatile, due to their susceptibility to recruitment and overfishing (Pierce and Guerra, Reference Pierce and Guerra1994). Therefore, if parasites are selected as indicators for stock assessment, it is crucial to carefully consider all the previously discussed sources of variability in order to obtain reliable results. Otherwise, differences between host populational units could be overestimated or, at least, derived from parasite tags varying for reasons other than those driving to actual dissimilarities between host stocks.

Data availability statement

Datasets are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Nucleotide sequences of the 28S rDNA of Clistobothrium sp. (OR725126 to OR725132) and Lacistorhynchidae gen. sp. (OR725133) were deposited in GenBank database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank María Isabel Lohfeldt for providing the samples from the commercial catches.

Author contributions

M. P. G.: conceptualization, sampling, statistical analysis, writing original draft, writing review and editing. D. C.: sampling, writing original draft and writing review. P. E. B.: sampling, statistical and molecular analyses, writing original draft and writing review. A. L. L.: sampling. M. M. I.: sampling and molecular analysis. M. L. I.: provision of squid samples and results analyses. N. I. P.: provision of squid samples and results analyses. B. E.: provision of squid samples and results analyses. J. T. T.: conceptualization, statistical analysis, supervision and funding acquisition.

Financial support

Financial support was provided by grants from Fondo para la Investigación Científica y Tecnológica (PICT no. 2019-03376) and Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata (EXA 1104/22).

Competing interests

None.

Ethical standards

Not applicable.