Coeliac disease (CD) is an immune-mediated enteropathy triggered by the ingestion of gluten in genetically susceptible individuals that affects approximately 1 % of the population( Reference Sapone, Bai and Ciacci 1 ). Currently, a gluten-free diet is the only safe and effective treatment for CD( Reference Lerner 2 ).

Gluten is used extensively by the food industry in a wide range of products due to its chemical characteristics which confer firmness, elasticity, moisture and uniformity to food( Reference Zandonadi, Botelho and Gandolfi 3 , Reference Araújo, Araújo and Botelho 4 ). Nevertheless, there are health conditions related to gluten that limit its consumption by CD patients and beyond. A number of disorders are linked to gluten ingestion, such as dermatitis herpetiformis, gluten ataxia, wheat allergy and gluten sensitivity, all of which demand a gluten-free diet( Reference Sapone, Bai and Ciacci 1 , Reference Ludvigsson, Leffler and Bai 5 ).

According to the Codex Alimentarius, ‘gluten-free foods’ are those in which the gluten level does not exceed 20 ppm (mg/kg) in total( 6 ). However, in most countries there is no consistent monitoring process to assess gluten content in supposedly gluten-free foods, in order to guarantee safe products for CD patients( Reference Diaz-Amigo and Popping 7 ).

Hence, out-of-home eating may constitute a problem for these individuals( Reference Farage and Zandonadi 8 ). The presence of gluten in supposedly gluten-free products (GFP) might occur due to cross-contamination because of shared production areas, kitchenware not being sanitized properly and inadequate procedures by restaurant staff( Reference Araújo, Araújo and Botelho 4 ).

CD patients need to follow a gluten-free diet not only to prevent the occurrence of gastrointestinal symptoms, but also to reduce the risk for long-term complications( Reference Sainsbury and Mullan 9 ).

Therefore, the aim of the present study was to assess the safety of gluten-free bakery products for consumption by CD patients and other individuals who require a gluten-free diet.

Methods

Sampling

A list of all bakeries in Brasilia (Brazil) was created, based on registrations in the city’s telephone register and the Commercial Registry’s record of bakery establishments. A total number of fifty-eight bakeries was obtained. All bakeries (n 58) were contacted by telephone in order to check whether they sold GFP and, if so, which products they had in their assortment. These GFP were compiled into a list.

All bakeries (n 58) were considered for the sampling process. The sample size was calculated through simple random sampling without replacement for a finite population, adopting a 5 % significance level. The variance considered was 0·25 since there is no information about it in the reference population. The final sample consisted of twenty-five bakeries (n 25) and the establishments were selected randomly.

Collection of food samples

According to the list of GFP obtained, the items were categorized into the following groups, organized in order of highest frequency: (i) cheese bread or cheese biscuit (100 %); (ii) tapioca flour biscuits (paulista biscuit; peta biscuit; cracknel; 72 %); and (iii) gluten-free cake or bread (44 %).

In each bakery, the samples were collected three times, on three different days. The bakeries were visited without previous contact and the samples were purchased by the researcher as a regular consumer would do. One sample from each available group of products was collected during these visits, in order of priority considering the highest frequency of the item within the groups. So, if there was cheese bread and cheese biscuit on the same day, cheese bread was purchased over the cheese biscuit since it was the most frequent product among the group according to the data collected via the telephone call. Thus, the collection was limited to a maximum of three products for each bakery, if all three categories of products were available on the day of the visit.

It is noteworthy that only the products identified as gluten-free were purchased. In order to be considered gluten-free, the product should fulfill at least one of the following criteria: (i) presence of ingredients list with no gluten-containing ingredient described on the product; (ii) presence of the claim ‘gluten-free’ on the product label; and (iii) bakery staff referred to the product as being gluten-free during the visit. This approach was used to select the samples as it closely resembles the approach behaviour of a typical CD patient looking for gluten-free foods. Gluten-free and gluten-containing foods were produced in the same production routine in all the bakeries, as checked by the researcher. A total of 130 samples were collected and evaluated.

Preparation of food samples

Samples were homogenized using a food processor. All surfaces, instruments and equipment used had been (previously) cleaned with water, regular detergent, Triton X (a detergent to remove proteins such as gluten; 3 % v/v solution), distilled water and ethanol (70 % v/v solution) in order to prevent any gluten contamination. This cleaning procedure was also carried out between the homogenization process of each sample, to avoid contamination among them, as proposed by Silva( Reference Silva 10 ).

Laboratory analysis

For the extraction of gluten, the extraction cocktail solution (R7016) from R-Biopharm (Darmstadt, Germany) was used, according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

The ELISA R5 technique was selected for the quantification of gluten and the RIDASCREEN® Gliadin kit (R7001) from R-Biopharm was used, following the manufacturer’s protocol. The samples were analysed in triplicate.

The test results were given through absorbance, where the average of the triplicate analysis results of each sample was put on a curve in order to determine the gluten concentration of the sample in ppm. The curve was calibrated using a regression with the gluten concentration on the x-axis and the absorbance on the y-axis. The values of each result of the five flasks of gluten standard of the kit used, containing 0, 5, 10, 20, 40 and 80 ppm of gluten, respectively, were entered in order to form the curve.

Statistical analysis

For data analysis, the statistical software package IBM SPSS Statistics Version 20.0.0 and Microsoft® Excel version 2013 were used.

Results and discussion

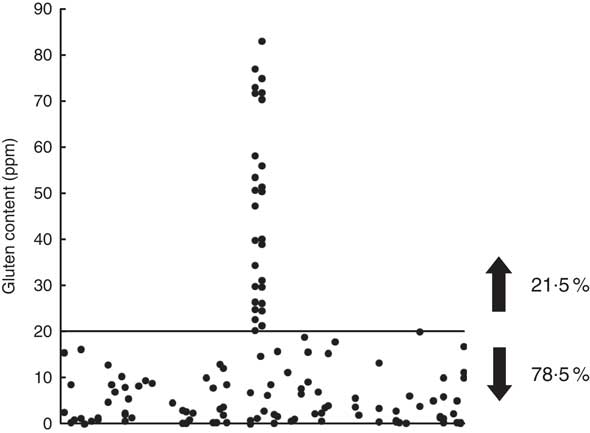

When removing gluten from the diet, it is common to search for alternatives derived from cassava and corn( Reference Silva 10 ). As such, we expected GFP found in the bakeries to be a viable choice for CD patients. However, laboratory tests revealed that out of the 130 samples analysed in total, 21·5 % (n 28) had a gluten contamination above 20 ppm (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Quantification of gluten in gluten-free products sold at twenty-five bakeries in Brasilia (Brazil), 2014. Of the 130 samples analysed, 21·5 % were above the threshold of 20 ppm gluten considered the safe upper limit for gluten-free food as proposed in the Codex Alimentarius

These figures are higher than those found by Oliveira et al. in bean samples from self-service restaurants (16 % of contamination)( Reference Oliveira, Zandonadi and Gandolfi 11 ). In the study by Silva, a total of 11·4 % of contamination was observed in processed GFP( Reference Silva 10 ). Laureano also examined processed GFP and found 12·9 % of contamination above 20 ppm( Reference Laureano 12 ). However, a higher percentage of contamination was expected in the present study since the baking environment involves an extensive manipulation of wheat flour, which increases chances of cross-contamination.

The results raise concern since bakeries are highly frequented by a broad range of consumers for reasons like convenience, practicality, location and opening hours( Reference Germano, Boanova and Matté 13 ). Moreover, the availability of products that are naturally gluten-free and frequently consumed by the population in general, such as cassava and corn products, could attract CD patients and others looking for GFP.

The situation becomes even more concerning considering that 64 % of the bakeries (n 16) in the current study sold at least one contaminated ‘gluten-free’ product. Only nine establishments (36 %) had no gluten-contaminated products in our sample.

Furthermore, it is noteworthy that only 6·2 % of the sampled products displayed ingredient lists on the label, which could cause coeliac individuals difficulties when analysing a product for purchase. Of those products with ingredient lists that listed gluten-free ingredients, a total of 21·3 % were contaminated. The ‘gluten-free’ claim was present only on the gluten-free bread products sampled (1·5 %). A possible explanation for this is the fact that the Brazilian legislation only demands such a claim for industrially processed food( 14 ).

In 92·3 % of the cases, the bakery employee verbally provided the information that the product was gluten-free. However, 23·7 % of these products were contaminated. This result is in agreement with findings from other studies that show restaurant staff are not always well versed in CD and gluten contamination issues( Reference Karajeh, Hurlstone and Patel 15 – Reference Laporte and Zandonadi 18 ). Therefore, the employees, to the best of their knowledge, state the information they have and believe to be true.

When analysing contamination by product category, cake products had the highest percentage of contamination (66·7 %), followed by biscuits (31·8 %) and cheese bread (8·3 %).

In order to prevent gluten cross-contamination, the Codex Alimentarius advocates the implementation of good manufacturing procedures( 6 ). However, most restaurants in Brasilia do not comply with the requirements established in this system, as revealed in a study by Akutsu et al.( Reference Akutsu, Botelho and Camargo 19 ). This finding hampers the establishment of having a gluten-contamination control programme, since neither sanitary prerequisites are met nor is there standardization of the processing steps to guarantee safe products.

International studies have also identified gluten cross-contamination as a concern( Reference Thompson, Lee and Grace 20 , Reference Gélinas, McKinnon and Mena 21 ). The production of safe GFP comprises a complex process. However, it is essential for improving the quality of life of CD individuals.

In some countries, control programmes for the prevention of gluten cross-contamination have been created and implemented in food industries and services( 22 – 28 ). These programmes are mostly based on the HACCP (Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points) method. The HACCP principles are used as a tool to minimize the risk of occurrence of undesired events by controlling procedures on specific critical points. The challenge of introducing these principles in Brazil may be even greater as basic sanitary prerequisites such as the good manufacturing procedures are not yet met( Reference Akutsu, Botelho and Camargo 19 ). Considering the extensive manipulation of wheat flour in bakeries, this environment may be considered an even more vulnerable spot for gluten cross-contamination. A first step could be to install separate production areas for gluten-free and gluten-containing foods.

The presence of gluten traces in GFP can cause health problems for individuals with CD. Hollon et al. investigated cases of patients who were not responsive to a gluten-free diet (refractory CD) and found that many had been incorrectly diagnosed and were actually exposed to contaminated products. These findings reaffirm that the presence of gluten traces may prevent histological and clinical recovery of patients with CD, even leading to an incorrect diagnosis of refractory CD, which could result in unnecessary use of immunosuppressive therapy( Reference Hollon, Cureton and Martin 29 ).

The sample in the current study was composed of randomly selected bakery establishments and as such it is representative of the bakeries in the city of Brasilia (Brazil). However, it is important to mention the limitations of the study, such as the lack of similar studies for the comparison of results and the impossibility of tracking and analysing the ingredients used in the preparation of the GFP.

Another important issue is related to the analytical method used. Choosing the ELISA R5 technique hampers comparisons with the results from other studies which analysed gluten content in foods by means of other techniques. Despite being accepted as the gold standard for gluten analysis by the Codex Alimentarius Commission and the Association of Official Analytical Chemists, this technique requires at least two epitopes in the protein. However, in hydrolysed foods, proteins are fragmented during food processing and converted into peptides in which only one toxic epitope may appear( Reference Mena, Lombardía and Hernando 30 ), which can compromise part of the results.

Conclusion

The immune system reacts to and deals with gluten in distinct ways, which is why there is a diversity of gluten-induced conditions currently diagnosed. The treatment for CD and all gluten-related disorders, however, consists of the removal of gluten from the diet. Essentially, about 10 % of the population needs to adopt a gluten-free lifestyle. Therefore, there is an urgent need to provide gluten-free foods for those who need them.

The present results indicate that gluten contamination in supposedly gluten-free bakery products is a reality for CD patients. This situation is highly concerning, not least due to increased numbers of meals eaten out of home. The unavailability of safe gluten-free foods directly affects the quality of life of patients with CD and as such it is essential to design viable and effective strategies to prevent contamination, including respective legislation, control measures and supervision by competent agencies.

Acknowledgements

Financial support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: The authors’ contributions were as follows. P.F.: conception and design of the study; acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript. Y.K.d.M.N.: conception and design of the study; analysis and interpretation of data; supervision; critical revision of the manuscript. R.P.: conception and design of the study; supervision; critical revision of the manuscript. L.G.: conception and design of the study; supervision; critical revision of the manuscript. P.A.: analysis and interpretation of data; critical revision of the manuscript; statistical analysis. R.P.Z.: conception and design of the study; analysis and interpretation of data; supervision; drafting and critical revision of the manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: Not applicable.