Nutrition is now the main risk factor influencing the burden of disease globally( Reference Lim, Vos and Flaxman 1 ). In response, there are calls for ‘inter-sectoral’ food and nutrition policies that address the social, environmental and health dimensions of food systems, and that emphasise cross-government coordination and broad stakeholder participation in policy development( 2 ). However, there are challenges in developing such policies due to the complexity of the issues and the tensions between sectoral interests( Reference Lang, Barling and Caraher 3 ).

The purpose of the present article is to critically analyse the development process for the Australian National Food Plan (also referred to as ‘the Plan’ hereafter) as a case study of contemporary food and nutrition policy making. The processes of consultation and stakeholder involvement in the development of the Plan are addressed, as is the power exerted by various industry groups. The article ends by exploring the fate of the Plan after a change in federal government in late 2013.

Background

The declaration of the International Conference on Nutrition and commitments to the World Food Summit in 1992( 2 ) obligated national governments to develop and revise National Plans of Action for Nutrition. A key message from the 1992 commitments was that plans should be inter-sectoral, placing nutrition in the context of broader food system influences on consumption, and involving all relevant government departments in the development of plans, including departments of agriculture and trade, as well as health. In practice, countries have continued to develop separate nutrition policies alongside food security and/or agricultural plans( 2 , Reference Nishida 4 ). These developments have been led by national governments, although as civil society and consumer concern about the global food system has grown, this has led to increasing involvement of other stakeholders in the development of food polices( Reference Carolan 5 , Reference Kneafsey, Cox and Holloway 6 ).

Prior to the 2013 National Food Plan, there had been several attempts in Australia to develop ‘inter-sectoral’ food and nutrition policies at national( 7 ) and state level( Reference Lawrence 8 , Reference Powles, Wahlquist and Robbins 9 ). In particular, the 1992 national food and nutrition policy( 7 ) was far-sighted in its statements that ‘the food and nutrition policy needs to be wide ranging and to ensure that the impacts of individual programs are examined throughout the food and nutrition system’ and that ‘the food and nutrition policy acknowledges the importance of ecological sustainable development so that resources are managed to ensure good health for future generations’. However, the policy received little support for its implementation and foundered. State food policy initiatives were also dominated by agricultural and food industry interests( Reference Alden 10 – Reference Caraher, Carey and McConell 12 ). Australia is a significant food producer, exporting about 60 % of the food that it produces( 13 ). Related to this export focus, over the last three decades, food policy in Australia has been characterised by an emphasis on agricultural and trade policy and by a neoliberal, market-driven agenda( Reference Caraher and Coveney 14 ).

In 2009, both the public health sector and the food industry released position papers calling for the development of a national food policy( 15 , 16 ). The position statements released by the Public Health Association of Australia (PHAA)( 16 ) (the peak body for the Australian public health sector) and the Australian Food and Grocery Council( 15 ) (the peak body for the food manufacturing sector) differed in many respects, particularly in their relative emphasis on health and trade concerns. However, both called for an ‘integrated’ or ‘whole of government’ policy that included all relevant government departments in its development and both also highlighted concerns related to future environmental challenges for food production. Shortly after the Labor Government was re-elected in late 2010, it announced that it was beginning work on a National Food Plan that would ‘integrate all aspects of food policy by looking at the whole food chain, from the paddock to the plate’( 17 ). Carcasci’s research( Reference Carcasci 18 ) suggests that the release of the Food Matters report( 19 ) by the UK Cabinet Office in 2008 was influential in the Australian Government’s decision to develop a National Food Plan, along with the Australian Food and Grocery Council’s position paper( 15 ).

Methodology

The present article uses a critical policy-based research approach, drawing on analysis of a variety of policy documents from key stakeholders relating to the development of Australia’s National Food Plan( Reference O’Connor and Netting 20 ). The document analysis focuses on the chronological stages of the development of the National Food Plan, identifying the key actors that influenced the Plan’s development. We also describe how the National Food Plan was shaped by the interests of those key actors and by the broader policy context in which the development of the Plan took place.

Data collection

Data were collected from a range of policy documents at three key stages of the policy development process. The three stages of policy development were typical of a ‘Westminster’ policy process. An issues paper was released by the Government, then a green paper and a final white paper, with public consultations at the first two stages of the process when stakeholders were invited to make submissions (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Stages of development of Australia’s National Food Plan from August 2010 to May 2013

The following types of documents were collected: (i) government discussion papers (the issues paper, green paper and white paper); (ii) stakeholder submissions to the issues paper and green paper; (iii) position papers and other policy documents from stakeholders related to the development of the Plan; and (iv) media releases from government and other stakeholders about the Plan. All the documents collected were publicly available. Submissions to the issues paper and green paper were downloaded from the website of the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry (DAFF), the lead government agency in the development of the Plan (see below). The submissions have since been archived and are no longer publicly available. Government discussion papers were also downloaded from the DAFF website. Other documents, such as media releases and position papers, were downloaded from the websites of key stakeholders. In addition to documents related to the three key stages of the policy’s development, information about other aspects of the policy development process – such as the establishment of the National Food Plan Unit and the Food Policy Working Group – was also gathered from the DAFF website. Documents were collected between June 2009, when stakeholders began calling for the development of a national food policy, and May 2013, when the final version of the National Food Plan was released.

Data analysis

Analysis of data in the present research draws on two analytical approaches: Walt and Gilson’s( Reference Walt and Gilson 21 ) health policy triangle and Kingdon’s( Reference Kingdon 22 ) policy streams model.

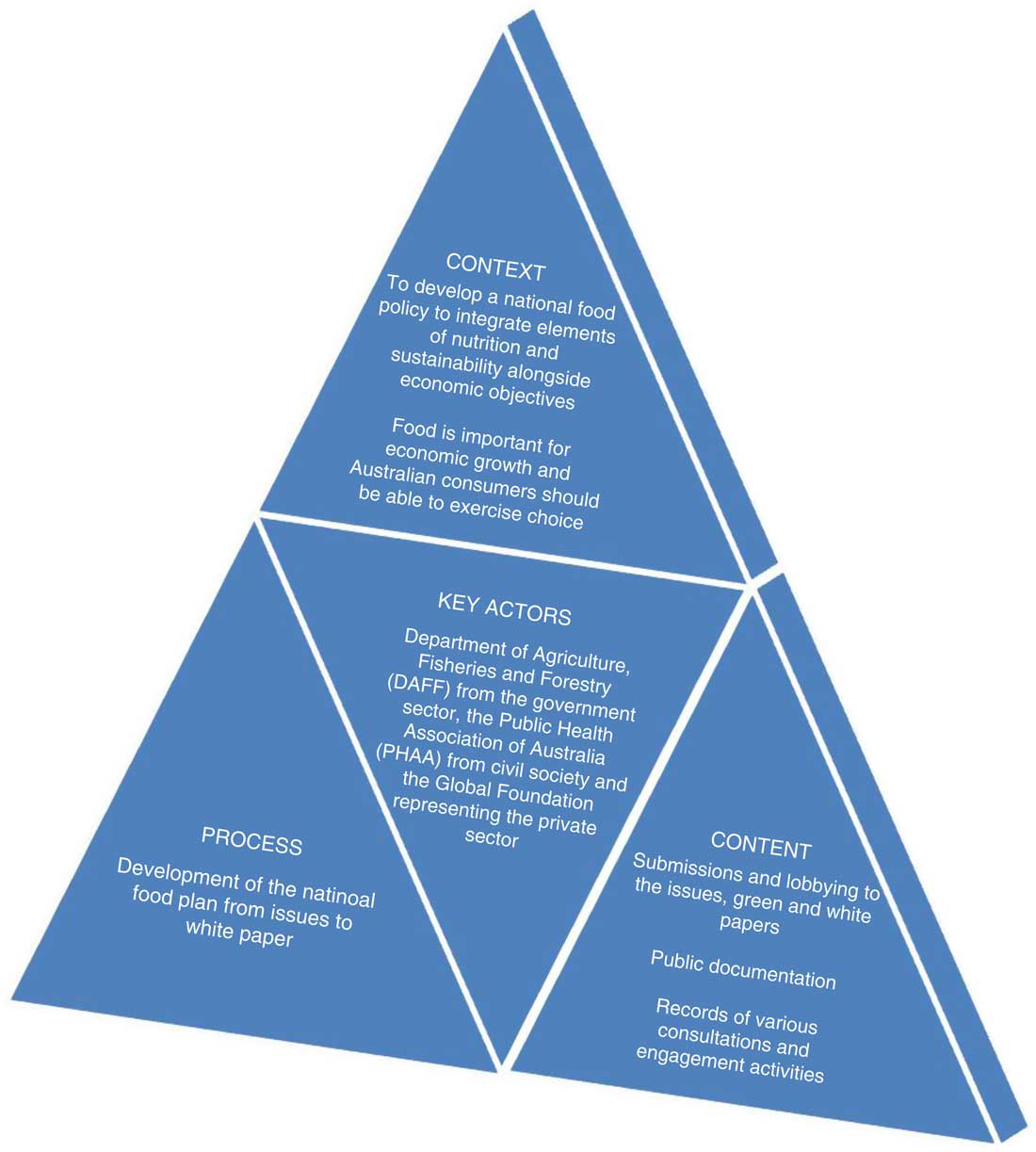

Walt and Gilson’s health policy triangle( Reference Walt and Gilson 21 ) was used as an organising framework to analyse how the Plan was developed and who was involved in its development (see Fig. 2). The policy triangle approach explores the role of actors informed by the context, process and content of policy development( Reference Walt and Gilson 21 ) and enables a generalized map of a policy area to be developed to aid systematic thinking( Reference Buse, Mays and Walt 23 ). This structure was used to organise and filter the documents gathered, first chronologically, then based on actors and stakeholder interests and positions. As Walt et al.( Reference Walt, Shiffman and Schneider 24 ) observe, policy analysis is a multidisciplinary approach ‘that aims to explain the interaction between institutions, interests and ideas in the policy process’ (p. 308). We would add that it is also multilevel in that interests and institutions operate at different levels in the policy world, from local to national. This is the case in Australia, which is a federation of states and independent territories with a parliamentary ‘Westminster’ system of government.

Fig. 2 The policy triangle as applied to the development of Australia’s National Food Plan (adapted from Walt and Gilson( Reference Walt and Gilson 21 ))

The perspectives of multiple researchers aided the development of a critical understanding of the policy process. Submissions to the public consultations for the National Food Plan were read by two of the researchers and an initial categorisation was made of the actors, sectors and interests that they represented. The two researchers then cross-checked their findings and further refined the categories. The results of this categorisation were read at a later stage by the two other authors. This informed the process of identifying the sectors that made submissions to the policy development process and the key actors within those sectors who were representative of the interests and tensions identified. We identified actors using the tripartite approach to food supply advocated by Lang and Heasman( Reference Lang and Heasman 25 ) of three key actors: civil society, the private sector and government.

Walt and Gilson’s( Reference Walt and Gilson 21 ) framework was augmented using Kingdon’s( Reference Kingdon 22 ) ‘policy streams model’. Kingdon argues that for a new policy to be developed and implemented, three different policy streams need to converge – problem, policy and politics – to create an active policy window, in which a new policy can be formed and implemented. Policy making is messy, with evidence playing one part and lobbying and vested interests shaping the eventual policy( Reference Kingdon 22 ). Drawing on the comparative work of Zahariadis( Reference Zahariadis 26 ), Cairney( Reference Cairney 27 ) argues that the strength of this multiple streams approach to understanding policy decisions is in its ‘explanatory power’ (p. 240). Kingdon’s model allows the overall policy context to be explored, so that events beyond the submissions in terms of the politics of the time are used to frame the developments of the policy. This does not necessarily mean that the correct policy decisions are always reached, but that we can look to underlying influences beyond evidence in the process of food policy making( Reference van Zwanenberg and Millstone 28 ). It is for this reason that Kingdon’s approach is used as a framework for analysis. In the context of the present research, the potential points at which the policy ‘streams’ could overlap were the three key stages of the policy development process: the initial issues paper and the green and white papers.

Cairney( Reference Cairney 27 ) suggests that the most efficient process for analysing public policy is twofold. First, mapping the policy development process provides a direction of travel for research. Initial mapping of the process was undertaken through policy scoping and document review, which identified relevant documents and drew out themes for analysis. The development of the Plan then became a case study of influence and an example of what Bell( Reference Bell 29 ) calls ‘policy story-telling’. The present article analyses the how of the policy processes and who (which actors) have been involved in the development of the process. We move from the general to the specific, using a case study approach, to show how key actors were involved in the process of influence.

Key actors

Walt et al.( Reference Walt, Shiffman and Schneider 24 ) highlight that within health policy analysis ‘it can be difficult to “tell the story” without getting immersed in the detail’ (p. 310). In order to address the risk of getting lost in the complexity, we chose to focus on the activities of one key actor representing each apex of the policy triangle: DAFF from the government sector, the PHAA from civil society and the Global Foundation from the private sector (see Table 1). The three policy actors were chosen on the basis of their role in the development of the Plan.

Table 1 Key actors in the development of Australia’s National Food Plan

DAFF was chosen as a government actor because it was the lead federal government agency involved in the development of the Plan (see Results section). Australia is a federal nation, and the federal and state governments share responsibility for aspects of health, environment and agricultural policy. As a result, there are both horizontal and vertical policy streams between the federal government and the states, as well as across states. The development of the National Food Plan was led by DAFF (the federal department for agriculture) and individual states made submissions during the consultation process.

The PHAA was chosen as the key civil society actor because it is the national peak body for public health in Australia and played a significant role in advocating for the development of an integrated national food policy, with nutrition and sustainability as a central focus( 16 , 30 ).

The Global Foundation was chosen as the key private sector actor because of the significance of its activities in relation to the development of the National Food Plan (see Results) and because of the involvement of some of Australia’s most powerful food industry stakeholders in these activities. The Global Foundation is a registered charity with links to key stakeholders in the private sector. The Global Foundation established a Food Security Working Group in 2009 that included representatives of Woolworths (one of Australia’s two main retailers), the Australian Food and Grocery Council (the national peak body representing food manufacturers)( Reference Mayes and Kaldor 31 ), the National Farmers’ Federation (the national peak body representing farmers) and the CSIRO (Australia’s national science agency)( 32 ).

Many other actors were involved in the development of the Plan, and this can be seen in the several hundred written submissions received on the issues paper and the green paper. Although we focused primarily on three key actors, we also drew on wider sources and documents from other actors. These actors are introduced in the Results where relevant.

Results

Policy development process

The National Food Plan was developed over two-and-a-half years between December 2010 and May 2013. The development of the Plan is described in terms of three key stages: the Issues Paper, Green Paper and the finalised White Paper. Prior to the Plan’s development, a National Food Plan Unit was established to lead the development of the Plan within Government and a National Food Policy Working Group was set up to advise on its development. These are also described.

The National Food Plan Unit and the National Food Policy Working Group

A National Food Plan Unit was established to coordinate development of the Plan under the leadership of the Minister for Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry. The Unit was based in the Agricultural Productivity Division of DAFF. The Minister for Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry was said to be ‘working closely with relevant ministerial colleagues to ensure a whole-of-government approach’ to the development of the Plan( 33 ). However, the location of the National Food Plan Unit within the federal department of agriculture stood in contrast to the development of the UK’s integrated food policy, Food 2030( 34 ), which was coordinated directly by the Prime Minister’s Cabinet Office( 19 ). The decision to locate the National Food Plan Unit within DAFF was an early indicator of the direction that the Plan would take.

A National Food Policy Working Group was set up in December 2010 ‘as a forum for active communication between the food industry and government’( 35 ). Of the thirteen members of the Working Group, ten were from the agriculture and food industries; there was just one consumer representative and one health representative. Some of the most powerful stakeholders in the agri-food sector in Australia were represented on the Working Group, including the National Farmers’ Federation, the Australian Food and Grocery Council and Woolworths (one of two major food retailers in Australia, the other is Coles). These organisations were also key members of the Global Foundation’s Food Security Working Group( 32 ).

The dominance of agriculture and food industry representatives on the Working Group led to criticism from the health sector that the working group was ‘stacked with industry’( Reference Sweet 36 ) and concerns that health, consumer and environment advocates had effectively been ‘locked out’ of the key policy forums. There was also criticism that there was a lack of transparency in the activities of the Working Group, as the agendas and minutes of meetings were not made public( 37 ).

The sectors that were under-represented in the National Food Policy Working Group responded in several ways. A number of grass-roots civil society groups came together after the August 2010 pre-election announcement to write an open letter to politicians, expressing their concern that the development of the policy should be an open and democratic process that reflected the interests of all Australians. Many of the signatories of this letter went on to form the Australian Food Sovereignty Alliance, which became a significant civil society actor in the national food policy arena, developing an alternative policy framework to the National Food Plan, The People’s Food Plan( 38 ).

The Issues Paper (June 2011)

The Issues Paper presented a view that Australia was essentially ‘food secure’, emphasising that 60 % of the country’s food production was exported. The overall emphasis of the Issues Paper was on maximising food production and promoting a ‘competitive, productive and efficient food industry’( 39 ). This view was criticised by academics, civil society and public health stakeholders, who argued that a fundamental shift was needed to a fair, sustainable and healthy food system( 40 – 42 ). The criticism came in the form of policy position papers( 37 ) and media releases( 41 ), as well as submissions to the public consultation on the Issues Paper( 42 , 43 ).

The Issues Paper placed relatively little emphasis on the potential of climate change and other environmental pressures to impact Australia’s future food security, and had little to say on nutrition and public health concerns. The Paper also placed little emphasis on the role of government intervention to address the drivers of obesity, indicating its preference for an approach based on consumer choice: ‘the government’s policy is to allow commercial entities to position themselves to facilitate consumer preferences’( 39 ) (p. 41). When the development of a National Food Plan was announced in 2010, health and nutrition were initially excluded from the first phase of the Plan’s development. The first phase was to concentrate on developing ‘a strategy to maximise food production opportunities’ and health and nutrition was to be considered in a second phase after a major national review of food labelling had concluded( 17 ). After public criticism of this neglect of public health concerns( Reference Sweet 44 ), the two-stage process was abandoned.

DAFF gathered feedback on the Issues Paper through roundtables, a public webcast and written submissions. There was continuing criticism from some civil society groups about a lack of transparency during the consultation process, particularly in relation to a series of ‘invitation only’ roundtables that took place in August 2011( 40 ). Little public information was made available about the roundtables initially, although lists of attendees and a summary of the roundtable consultations were later published. Of the 180 stakeholders who attended roundtable meetings, just over 60 % were from the agriculture and food industries (and associated parts of the food supply chain), 9 % were from consumer and community groups, and 7 % from the health sector( 45 ). Other attendees came from a variety of sectors, including regional development, research and development, and education.

Over 270 written submissions were made to the Issues Paper, with the greatest number of submissions – about 30 % – being made by industry and agricultural stakeholders. Just over 20 % of submissions came from individuals, about 7 % from local, regional and state governments, 3 % from academic institutions and about 5 % from actors in the public health sector. The majority of other submissions came from civil society groups across a wide range of sectors, including groups focused on social justice, animal welfare, consumer rights and environmental issues. The number of written submissions from key sectors contrasts with the involvement of these sectors in the roundtables, described above. The Global Foundation made a submission to the Issues Paper that outlined its vision of increased food exports: ‘with a forward thinking and comprehensive food plan, Australia has the potential to become a major exporter of high value-added food products’( 32 ). The submission also described the involvement of its own Food Security Working Group in the genesis of the Plan. The Australian Minister for Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry attended three meetings of the Global Foundation’s Food Security Working Group prior to the announcement of the National Food Plan, where the need for a national food security strategy was discussed. This Food Security Working Group continued to collaborate closely with the Minister during the development of the Plan( 32 ).

The PHAA responded to the Issues Paper by submitting a response to the consultation( 42 ) and by developing its own position paper, A Future for Food 2, which outlined the PHAA’s vision of a healthy, sustainable and fair food system( 30 ). A Future for Food 2 was an update of an earlier position paper, A Future for Food ( 16 ), which was released prior to the development of the Plan and had called for the development of ‘a national integrated food policy’ (p. 3); as Crotty( Reference Crotty 46 ) puts it, a way of linking ‘pre-swallowing’ to ‘post-swallowing’ sciences.

Green Paper (July 2012)

The Green Paper comprised a set of possible policy options and directions for the Plan. It outlined an overarching vision of ‘A sustainable, globally competitive, resilient food supply, supporting access to nutritious and affordable food’( 47 ) (p. 2) and proposed seven key objectives, one of which related specifically to health: ‘Reduce barriers to a safe and nutritious food supply that responds to the evolving preferences and needs of all Australians and supports population health’( 47 ) (p. 2). The overall emphasis of the Green Paper was on increasing agricultural productivity and promoting the competitiveness of the food industry, and the paper proposed an ambitious target of doubling food exports to Asia.

Stakeholders in the agriculture and food industries largely welcomed the Green Paper( 48 , 49 ). However, civil society stakeholders described the Green Paper as a ‘plan for large agribusiness and retailing corporations, rather than a plan for all Australians’( Reference Rose and Croft 50 ). The PHAA published a scorecard of public health objectives that it intended to evaluate the Green Paper against( 51 ).

Feedback on the Green Paper was gathered via written submissions, at a series of public meetings and at eight invitation-only ‘CEO-level’ roundtable meetings. There was criticism from civil society groups that the public consultation process was inadequate, as public meetings were over-subscribed and some people were excluded from the process( 52 ). In addition to the public consultation process, meetings were held with state and territory governments and a small number of roundtables were held with ‘key representatives from across the food system supply chain’( 45 ).

Just over 400 submissions were made to the Green Paper. The PHAA submission argued that the Green Paper was a ‘“business as usual” plan focusing on the economic value of all food production’ and that securing a healthy and sustainable food supply should come before economic considerations( 53 ) (p. 12). The Global Foundation did not make a submission to the Green Paper. However, in May 2012, a few weeks before the Green Paper was released, the Australian Prime Minister, Julia Gillard, gave a speech at the Global Foundation’s annual summit( Reference Gillard 54 ) at which she emphasised Australia’s potential to become a ‘regional food superpower’ and a ‘provider of reliable, high quality food to meet Asia’s needs’, echoing elements of the Global Foundation’s submission to the Issues Paper( 32 ).

In her speech, the Prime Minister also highlighted a connection between the National Food Plan and the Australia in the Asian Century White Paper( 55 ), which was then in the final stages of development. The Australia in the Asian Century White Paper( 55 ) was to be a key part of the Gillard Government’s policy platform, outlining a plan for Australia to take advantage of economic growth in Asia. The Australia in the Asian Century White Paper was released in October 2012, and the agriculture and food sectors featured strongly, with a vision that ‘Australian food producers and processors will be recognised globally as innovative and reliable producers of more and higher quality food and agricultural products, services and technology to Asia’( 55 ) (p. 28).

National Food Plan White Paper (May 2013)

The White Paper( 13 ) outlined four key themes: ‘Growing Exports’, ‘Thriving Industry’, ‘People’ and ‘Sustainable Food’ (see Table 2). The Paper also described the initiatives through which the themes would be implemented and the funding that would be allocated to each initiative. The first two themes, ‘Growing Exports’ and ‘Thriving Industry’, dominated. These two themes attracted over 90 % of the $AU 42·8 million total funding allocated to implementing the Plan, leaving the themes of ‘People’ and ‘Sustainable Food’ with less than 10 % of the funding. The allocation of funding was indicative of the Plan’s major thrust and direction: the idea that Australia could become a ‘food bowl for Asia’, echoing the vision of the Global Foundation( 32 ) and the Australia in the Asian Century White Paper( 55 ). About 80 % of funding was allocated to investigating and building ties with Asian food markets, and included goals to increase food exports by 45 % and to grow agricultural productivity by 30 %( 13 ). The goal of increasing food exports by 45 % had been watered down from an earlier goal in the Green Paper of doubling food exports, after criticism from some stakeholders that this was unrealistic, given increasing environmental constraints on food production( 56 ).

Table 2 GoalsFootnote * in the green and white papers on Australia’s National Food Plan

* Some goals in this table have been paraphrased from the original for brevity.

Stakeholders from the food and agriculture industries largely welcomed the White Paper( 57 , 58 ). However, civil society stakeholders were less welcoming, with the PHAA calling the Plan a ‘sop to industry’ and a ‘lost opportunity’( 59 ). One aspect of the Plan that attracted criticism will be explored further here: the sidelining of public health nutrition and environmental sustainability.

Public health nutrition and environmental sustainability

Public health nutrition featured in one of sixteen goals of the White Paper under the theme ‘People’. It was no longer a central objective as it had been in the Green Paper and had effectively been removed from the Plan altogether into the development of a new, but separate, National Nutrition Policy( 13 ). Furthermore, no new funding had been allocated to initiatives to tackle obesity; instead, the principles of ‘freedom to choose’ and ‘free and open markets’ formed central pillars of the Plan. The Plan stated: ‘Australians are free to make their own choices about food … we will only intervene to prevent harm or meet our international obligations. We will provide information so people can make “informed choices”’( 13 ) (p. 18).

Environmental sustainability was also largely overlooked in the Plan. No significant initiatives were proposed to shift food production to more environmentally sustainable approaches and there was little consideration of what increasing exports might mean for the long-term sustainability of Australia’s food production base. The Australian Greens (a national political party with roots in environmental politics) argued that the Plan failed to address the impact of climate change on food production( 60 ). About 17 % of Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions are related to agriculture( 61 ) and climate change is likely to lead to a significant reduction in water availability in Australia’s main food bowl, the Murray–Darling Basin( 62 ). The Plan said little about these issues and allocated no new funds to encouraging sustainable food production( Reference Friel, Barosh and Lawrence 63 – Reference Friel 65 ).

Discussion

The National Food Plan began with the stated intention of being an integrated national food policy, but evolved into an industry-focused plan in which both health and environmental sustainability were sidelined. Despite one Senator’s( Reference Boswell 66 ) claims that government departments are driven by the green agenda, the green and health lobbies were ineffective in advancing the case for health and climate change( Reference Rootes 67 ). The final Plan also had little focus on Australia’s domestic food supply and became primarily focused on increasing food exports to Asia. Yet Australia and its population also face food security challenges, such as food insecurity among vulnerable population groups and environmental limitations to food production, including water scarcity and soil degradation( Reference Huntley 68 , Reference Farmer-Bowers, Higgins and Millar 69 ). There were, however, some positive aspects to the Plan’s development, including the opportunities for stakeholder consultation through the process.

Issues of what Howlett( Reference Howlett 70 ) calls repeating policy cycles are evident, in the sense that the situation in 2012/13 echoes aspects of the 1992 attempt at integrated food policy development( 7 ). The central policy direction of increasing food exports to Asia was influenced to a significant extent by key players, such as the Global Foundation, ensuring that the problem, policy and politics streams came together in a similar way to previous occasions in 1987 and 1992, when business interests won the day. In Buse et al.’s( Reference Buse, Mays and Walt 23 ) terms, public health nutrition and sustainable food supplies have been removed from the content of policy development, a pattern repeated elsewhere( Reference Holdsworth 64 , Reference Friel 65 ).

Our analysis highlights how one of the key actors, the Global Foundation, used its ‘unique, bipartisan model of public–private cooperation on policy development’( 71 ) (p. 6) to enable key food industry stakeholders to collaborate with each other, and with government, in developing a clear vision for Australia’s food future. Such was the Global Foundation’s influence on the development of the Plan that the organisation describes itself as the ‘architect of Australia’s first national food plan’( 72 ). It seems that the Global Foundation operated beyond the formal submission and lobbying processes and was successful in gaining the confidence of politicians and civil servants. As a result, the Food Security Working Group established by the Global Foundation played an important role in shaping the Plan.

The policy development process for the National Food Plan also provided the food and agriculture industries with significant opportunity to influence the development of the Plan, as did its location within DAFF. The National Food Policy Working Group and roundtables to discuss the Issues Paper were both industry dominated. Assigning responsibility for the development of the Plan to DAFF, rather than to a cross-government Task Force, also cemented the influence of the federal department of agriculture and lessened the potential for other government departments, such as the federal Department for Health and Ageing, to influence the process. van Zwanenberg and Millstone( Reference van Zwanenberg and Millstone 28 ) describe a similar situation in the establishment of the UK Food Standards Agency, where despite initial calls for the Agency to deal with issues across the food chain, the issues of food safety and nutrition were separated from farm and export policy.

In contrast to the central role that the Global Foundation assumed in the Plan’s development, the PHAA and the public health nutrition sector were under-represented in the policy development process. The Global Foundation built a powerful alliance of stakeholders from across the food and agriculture sectors, but the PHAA engaged to a lesser extent in alliance building. Its two ‘A Future for Food’ papers( 16 , 30 ) presented an integrated vision of a ‘sustainable, healthy and fair’ food system, but it did not build strong cross-sector alliances with the broader movement of civil society groups who came together to form the Australian Food Sovereignty Alliance. This broader movement included groups focused on food sovereignty, community gardening, social justice and environmental sustainability( 38 , Reference Parker and Morgan 73 ). While the food and agriculture industries presented a coordinated agenda under the banner of the Global Foundation, the response from the public health sector was fragmented in comparison. Bronner( Reference Bronner 74 ) highlights the limits of public health nutrition and suggests that sometimes the best that can be hoped for is that nutrition policies are incorporated into public health policies. This seems to miss the opportunity to engage with the wider food system and to influence the determinants of poor nutrition at a structural level. Although cross-sector alliances can be fraught with difficulty and temporary in duration, as agendas may differ over principles and even evidence, the new ecological public health and sustainable diets agenda offers an opportunity for a broad alliance of (disparate) interests to come together in pursuit of common goals.

The Issues Paper, Green Paper and White Paper presented ‘windows of opportunity’ that were missed for public health nutrition to work together in a broad alliance with other sectors. The process and content from issues paper to white paper reflects the first shifting of the problem and the lack of an opportunity (or policy window) to address a comprehensive food policy where national interests were matched with those of export and economics. At the same time, the National Dietary Guidelines were being revised and even here the opportunity was lost to link food production and nutrition to sustainability( Reference Friel, Barosh and Lawrence 63 , Reference Rootes 67 ).

There emerges a lack of problem definition for policy to tackle, complicated by multiple diverging streams – for example, the divergence of agriculture and nutrition, export-oriented agriculture and local/regional food policy. There were no links or overlapping of the three streams of problem, policy and politics occurring as Kingdon( Reference Kingdon 22 ) contends. These data also illustrate other characteristics that depart from Kingdon’s( Reference Kingdon 22 ) model. The National Food Plan experience shows that the streams might be omnipresent, but they did not meander of their own accord. Instead, their route and the velocity with which they travelled were influenced by powerful actors who engineered the forging of where, when and under what circumstances the streams came together.

At a national level, a key outcome of the development of the National Food Plan has been a strengthening of the ‘food movement’ in Australia( 38 , Reference Parker and Morgan 73 ). The development of the National Food Plan brought together numerous community and environmental groups who found themselves under-represented in the policy development process. A number of these groups went on to form the Australian Food Sovereignty Alliance, releasing an alternative vision to the National Food Plan, The People’s Food Plan( 38 ). Alternatives are emerging to the neoliberal, economically focused food policies of national and state governments in Australia. They are emerging from local and regional governments and alliances of civil society organisations. These plans are partly a response to the failure of national food policy to address issues related to health, environment and social equity and to deal adequately with those issues alongside economic objectives. These alternative policies seek to integrate economic goals into broader agendas that promote a healthy, fair, sustainable and prosperous food system. Examples in the State of Victoria include the City of Melbourne Food Policy( 75 ) that was developed in 2012 and several regional food policies that are currently under development( 76 , 77 ). The challenge for these local movements will be to engage and remain policy relevant with the mainstream and not, as Guthman( Reference Guthman 78 ) reflects, by elevating the production and consumption of local food to the level of political action, a different form of consumerism and in itself a form of depoliticisation. These new social movements need to both work below the surface of the dominant food system to raise awareness but also to create new alliances to challenge policy( Reference Gros 79 ). The danger is that these new social movements themselves become divisive by engaging in what Melucci( Reference Melucci 80 ) calls ‘regressive Utopianism’ (p. 4).

A few months after the National Food Plan White Paper was released, the Labor Government lost the federal election and the Abbott Government (a Liberal–National Party Coalition) came to power with an agenda of a shrinking state and a belief in the neoliberal system to deliver benefits without government interference. The National Food Plan was quickly and quietly shelved, and the new Government began work on its own Agricultural Competitiveness White Paper( 81 ). The focus is firmly on identifying ‘pathways and approaches for growing farm profitability and boosting agriculture’s contribution to economic growth, trade, innovation and productivity’ and public health nutrition issues are not within scope. The development of a separate National Nutrition Policy continues, although little information has been made public about its development.

Although the National Food Plan has been shelved, the push for Australia to become the food bowl of Asia looks likely to gather pace. In effect, a food export plan is under development with little focus on health and sustainability concerns. The Global Foundation has advanced its policy platform on ‘Feeding Asia and the World’ with both the governing and opposition parties in Australian politics, and its vision of Australia as a ‘clean green foodbowl of Asia’ was evident in both the Coalition Government’s pre-election policy platform( 82 ) and the development of the Agricultural Competitiveness White Paper( 81 ).

Conclusions

The present article highlights how corporations and food industry interests shaped Australia’s National Food Plan. It underlines the message that policy making is not primarily based on objective evidence, but is shaped by other influences, such as politics and business. The study illustrates that it is no longer sufficient for the field of public health nutrition to engage solely in formal policy consultation processes. Public health nutrition, as a movement, needs to shift beyond traditional lobbying and evidence submissions to winning hearts and minds. Engaging broad public support and developing strong cross-sector alliances with civil society groups in the environment, social justice and community food sectors has the potential to achieve greater policy leverage. The evidence also suggests that engagement of the public health sector with industry should be approached with caution.

Finally, the article raises the question of whether pursuing a ‘whole of government’ food and nutrition policy is always the best option to achieve policy leverage for public health nutrition. In the case of Australia’s National Food Plan, the policy arena was dominated by powerful agri-food industry interests and responsibility for the Plan’s development lay with the federal agriculture department, rather than an inter-departmental unit. As a result, public health nutrition interests were squeezed out by a dominant trade agenda. Under these circumstances, the development of a national nutrition policy may offer the public health nutrition sector greater opportunity for policy influence than an integrated national food and nutrition policy. It remains to be seen whether this is the case in the ongoing development of Australia’s National Nutrition Policy. However, a key lesson for public health nutrition is the need to carefully assess policy environments to determine whether they offer the potential for a genuinely integrated food and nutrition policy that places health, social equity and environmental sustainability at the heart of the policy development process. The alternative, though, represents a continuation of existing approaches to nutrition policy, rather than addressing the need for a ‘whole of government’ food and nutrition policy that integrates the food chain from paddock to plate.

Acknowledgements

Financial support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. However, part of the research was carried out while R.C. was an employee of the Food Alliance, funded by VicHealth, and while M.C. was ‘Thinker in Residence’ at Deakin University, March–May 2012. Conflict of interest: R.C. is an employee of the Food Alliance, an organisation based at Deakin University that advocated on the development of the National Food Plan. M.C. was ‘Thinker in Residence’ at Deakin University, based at the Food Alliance, from March to May 2012. M.L. was the grant holder for the setting up of the Food Alliance. Authorship: R.C. and M.C. collected and analysed data, and were responsible for the first complete draft of the paper. M.L., S.F., M.C. and R.C. all contributed to subsequent drafts of the paper. Ethics of human subject participation: Ethical approval was not required.