The crisis in Syria since 2011 has broken many frontiers in terms of the horrific intensity of the fighting, its unpredictable spread across much of the country, its devastating effect on the civilian population and the indiscriminate use of terror and proscribed weapons. To this list can be added the number of deaths through the use of savagery for sheer shock effect and the vast displacement of the population, both internally and to neighbouring countries, even as far as Europe.

To regret the damage incurred to Syria's archaeological and historical sites is not to suggest that the cultural dimension rivals the human scale of the tragedy. In terms of physical damage to built structure, the loss of civilian housing stock greatly surpasses the extent of damage to historical buildings or archaeological sites.Footnote 1 Should we therefore be shocked when structures many hundreds of years old are destroyed? Should we even be surprised if at least two among the parties to the conflict go so far as to select buildings of great historic, religious or universal cultural value as targets in order to amplify the shock value of their mission – to show their determination to go beyond all bounds?

This article seeks to trace the reasons why participants in the Syrian conflict since 2011 have paid little attention to the norms of international law on the protection of heritage and monumental structures in conflict. It notes the main provisions under international law, the peculiar features of the Syrian conflict which have resulted in monuments becoming not simply incidental casualties but propaganda tools in the conflict, and the possible role of heritage reconstruction in a post-conflict context. It also seeks to give a tentative evaluation of the level of destruction of monuments in order to address the impression that the country's heritage has been irretrievably lost.

What we owe to Syria?

There are few countries that can rival Syria in terms of numbers of sites of archaeological and historical interest. It is simply an open book on the history of mankind over the last 10,000 years. While other countries may have brilliant phases of achievements on the scale of Egypt's Theban temples or Italy's Renaissance masterpieces, Syria has a continuous and more complex story to tell, one that draws in a wider catalogue of cultures of both the Mediterranean world and the key Islamic civilizations of the Middle East and beyond. This has been appreciated by a wider audience in recent decades, with over 100 foreign archaeological missions active in the country in any one year before 2011. During this time, the country's official body responsible for monuments and its thirty-four museums, the Directorate-General of Antiquities and Museums (DGAM), was active on an unprecedented scale.

In 1992, this author published Monuments of Syria, which was intended as the first comprehensive survey in English of the country's archaeological sites.Footnote 2 At the time, the number of foreign tourists was small, and many sites were poorly signposted and difficult to reach. The country was just beginning to feature on the tourist map and most places of archaeological interest were empty of visitors. Within twenty years, that had begun to change. Tourism had become the third-largest foreign exchange earner and an important means of regenerating the economy of many regions. By 2000 there were even many competing guide books available – not only five or six in English but a range in French, German, Italian, Spanish and Arabic.Footnote 3

As Syria began to flourish as a mass tourism destination, the country was particularly valued for the way its sites were presented, for the welcome its people extended to foreign visitors and, most encouraging of all, for the growing interest its own citizens took in the complexities of the country's past. Of course, there was an “agenda” whose subtleties were probably too suffused for most visitors to notice. Syria was presented as a civilization which was the sum of all its cultures, not a monoculture along the lines of the picture that even some European countries are still keen to present. Roman stood alongside Umayyad, Byzantine alongside Ottoman, each one not eliminating but building on the other. Research at Palmyra, for example, began to show that the Roman-era caravan city did not die with Rome's suppression of Zenobia's revolt in the late third century. Once a city of five temples, Palmyra later acquired an equal number of churches and eventually became a flourishing commercial centre of the early Arab period. Elsewhere, “Crusader” castles turned out to have important Mamluk or later phases, and the Crusaders’ ideas of a massive fortified enclosure, once the Westerner's prototype for all fairy-tale castles, were matched with a whole string of distinctly Arab fortresses previously only familiar as dots on a map.

So, what was the “agenda” that the monuments presented? It suited the Syrian government's professedly non-sectarian ideology to underline that Syria was not a monoculture – a product solely of one faith or ethnicity – but a rich tapestry built up over numerous migrations, virtually all of which had entered the country and lived alongside their predecessors without ongoing conflict.

The Hague Convention of 1954

It is not the purpose of this article to examine in what ways the parties to the Syria conflict have offended specific provisions of the 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict (1954 Hague Convention).Footnote 4 It is an unfortunate reality that most of the combatants are not conventional States who as signatories might be expected to be aware of their obligations under the provisions of the Convention, though of course ignorance is not an escape clause relieving parties of their obligations. In fact, the Convention provides a clear list of “dos and don'ts” which any party or group that takes up arms is nevertheless expected to observe, especially if it wishes to claim a place in Syria's post-conflict future.Footnote 5

In a conflict as savage as the one that has overwhelmed Syria, especially one which involves numerous outside participants with little stake or even interest in the country, there are many reasons why monuments become caught up in the intensity of war.

First, monuments just simply get in the way. Though international legal instruments such as the 1954 Hague Convention clearly seek to impose a moral obligation to quarantine the use of monuments as vantage points or targets, this author's view is that fighting groups have little interest in such “niceties” – or are not simply ignorant of but actively hostile towards them. The Convention specifically urges all parties to avoid the use of cultural properties for military purposes. However, prominent positions such as minarets or citadels which offer vantage points to fighters, often resistance forces using the mosques as barracks, have made such features particularly vulnerable.

Second, massive use of firepower in the form of intense shelling or area bombing has been a particular feature of this conflict, intended to clean out whole quarters and render them uninhabitable.

Third, particularly since 2014, groups who have joined the fighting have consciously chosen the destruction of heritage structures as a weapon of terror, seeking to reduce highly valued monuments to rubble through the massive use of explosives planted by tunnelling. Such operations profess ideological reasons, notably in the case of Islamist forces bent on the effacement of human or animal images or the elimination of monuments commemorating the dead. The perpetrators also seek to underline that they have no respect for the country's heritage and that they are prepared to go to any ends to convey their seriousness of purpose. The comparison with Pol Pot's return to a “Year Zero” in 1970s Cambodia seems apt.Footnote 6

Fourth, loss of central government control across much of the country before 2017 has lifted any restraints that official measures to protect cultural sites might once have imposed. Likewise, the lack of policing suggests that illegally excavated material can be more readily traded for profit given the increased opportunities for illicit traffic and eventual sale to dealers abroad.

It is also worth recalling that Article 23 of the 1954 Hague Convention stipulates that all States have an obligation to remove transportable cultural property out of harm's way and nominates the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) as the responsible international body charged with providing “technical assistance in organising the protection of (a nation's) cultural property”. All State Parties are also expected to take “all necessary steps to prosecute and impose penal or disciplinary sanctions upon those persons, of whatever nationality, who commit or order to be committed a breach of the present Convention”.

All of these provisions have been massively flouted in Syria, and all parties to the conflict have offended in one way or another. Moreover, external States (including States party to the Convention themselves) have provided funding or materiel to resistance elements deployed in Syria who have openly adopted some of the most flagrant acts of deliberate destruction as an essential part of their tactical procedures, even making them a centrepiece of the “image” they seek to promote in the outside world.Footnote 7

In the face of this situation, the Syrian heritage authorities (DGAM) have sought to do what they can to protect sites and work through the steps UNESCO has developed over the years to advise States Parties on appropriate protective procedures such as removing smaller items to safekeeping well out of the path of potential conflict. They have also continued to fund the salaries of DGAM staff even in areas beyond government control in the hope that they might still do what they can to secure sites and buildings and prevent illegal digging. In doing so these authorities have, in some areas, been quietly engaging the local villagers to deflect the attention of participants in the fighting away from cultural sites. Little publicity has been given to the DGAM's efforts to do what can be done in a wider environment of chaos to ensure cultural assets are not targets. It may not be an easy job in a war environment to ensure that citizens see monuments not just as pretty ornaments but as investments in their future, but the DGAM seems to have had some success, much of it necessarily away from the glare of publicity.Footnote 8

Assessing the toll

A useful form of outside monitoring which complements the picture of the damage to Syria's heritage is derived from satellite imagery, but there are limits to the scope of such information if it is assessed in isolation. Resolution of satellite images is improving each decade, but satellite imagery necessarily cannot see what the eye or camera on the ground can perceive. It can, however, show patterns of activity, movements by intrusive forces and disturbances of the landscape, such as looting pits or the use of earth-moving equipment to expose remains below ground. In three revealing articles prepared in 2014–17, Jesse Casana, Mitra Panahipour and Elise Jakoby Laugier summarized the conclusions reached over five years of examination of sites using high-resolution satellite imagery.Footnote 9 The authors presented examples of the value of imagery in revealing the level of damage. They also reported on the distribution of sites at risk from looting, vandalism or exploitation for military purposes and the pattern of damage in relation to factional control within Syria. They hoped that this information would be “of value to heritage officials and archaeologists after the war in Syria has subsided, while also providing a model for remote sensing-based monitoring of archaeological sites in conflict situations more broadly”.Footnote 10

Casana and Laugier's 2017 summary of the programme's interim findings provided interesting results. Their analysis covered 3,641 sites in Syria, including unexplored sites whose terrain indicated promising features such as tells (archaeological mounds) and other formations indicating built remains. Unlike other studies, the research, funded by the American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR) with US State Department support, also compared post- with pre-2011 historical imagery, thus overcoming one of the credibility gaps in earlier surveys that did not exclude pre-conflict interventions, including looting pits.

The results can be summarized as follows:Footnote 11

• Of the 3,641 Syrian sites surveyed to 2017, pre-2011 imagery revealed illegal digging at 450 sites, with an additional 355 sites added in the post-2011 era.

• Ninety-nine of the sites already marked by looting pits before 2011 were active again post-2011; the rest were the work of looters exploring previously undisturbed sites.

• The proportion of sites affected by looting was around 17.04% (pre-2011), with an additional 13.44% added in the period 2011–17.

• The number of sites affected directly by military activity steadily increased during the period under review, reaching 103 in 2016, particularly at features used to garrison fighting units, for example through the use of heavy machinery, trenching, tank installations and troop housing.

• The intensity of looting in terms of the rate of interventions per year greatly increased over the years 2011 to 2014. When so-called Islamic State (IS) appeared on the scene in 2014–15, while the rate of deliberate destruction increased, the incidence of illegal digging decreased in terms of both severity and frequency.

What we don't know, of course, is what the looters found – what they managed to use for money-making ends and what might have been stored away for future sale. The extent of looting for profit (and the role of insurgent groups in encouraging, even licensing, the trade) is only known from a small number of anecdotal reports. Given that most artefacts can readily be traced as a result of the records available over 150 years or more of recording and analyzing pottery and decorative styles or technical data on the origins of stone or clay, the market abroad is possibly simply too “hot” to be exploited at the moment.Footnote 12 If most items go no further for the moment than the cellars of contraband handlers, the returns to the impoverished, perhaps even homeless illegal diggers might be minimal, with the trade for the moment relying mainly on fakes.Footnote 13

However, it is the more active intervention of two larger players which saw a marked increase in the intensity of destruction in 2015:

• conventional forces setting up firing positions often on prominent mounds or tells in contested territory,Footnote 14 and

• so-called Islamic State (which made an aggressive programme of destruction a central part of its campaign to project itself as a ruthless foe of all but the most basic or literal form of Islam) extending its operations from Iraq into Syria.Footnote 15

While looting may be the most widespread problem resulting from the breakdown of authority, the pattern of destruction among major archaeological sites varies considerably.Footnote 16 Some regions (notably those remaining in government hands) were untouched. Others bear the scars of occasional encounters between government and rebel forces. Some areas, however, have consistently been the scenes of major encounters, with fixed lines of battle strung across the historic centres of cities.Footnote 17

Monuments on the battle lines

The examples of Aleppo and Palmyra will perhaps best illustrate the devastating consequences of such persistent combat when modern explosives and weaponry are directed at ancient and medieval buildings, usually of stone. Most fortifications date back to pre-gunpowder eras and still have a robust resistance due to their massive bulk and heavy, well-laid masonry. They have had a good survival rate in this conflict. Most mosques, minarets, churches and historic houses, with their fragile structures and delicate embellishments, are more vulnerable.

The catalogue of monuments damaged or destroyed in the Syria conflict is necessarily still to be compiled. Virtually all sides to the conflict have been responsible for aspects of this destructive trail. At the time of writing, it seems reasonable to divide the pattern of destruction into five different categories.

• Struggles for tactical advantage, especially in urban conflict, touched off from the beginning by the deliberate choice of minarets or mosques/madrasas as vantage or refuge points.

• Operations to widen the margin of security around positions held by combatant forces.

• Application of heavy firepower or area bombing techniques in close urban engagements, particularly in order to force civilian populations to flee rebel-held areas.

• Deliberate adoption of buildings as targets for symbolic or propaganda purposes.

• Tunnelling to plant massive quantities of explosives with the aim of obliterating a building.

Two sites illustrate in different ways how the effect of prolonged conflict and the use of ruthless modern methods of warfare have had devastating consequences: the monumental historic zone in Aleppo and the main ruin field of the central desert caravan city, Palmyra.

Aleppo

The city of Aleppo contains one of the world's richest collections of monuments of the Islamic middle ages. Hundreds of buildings are on the register of the Syrian antiquities authorities, with a high percentage located within the city's medieval walls.

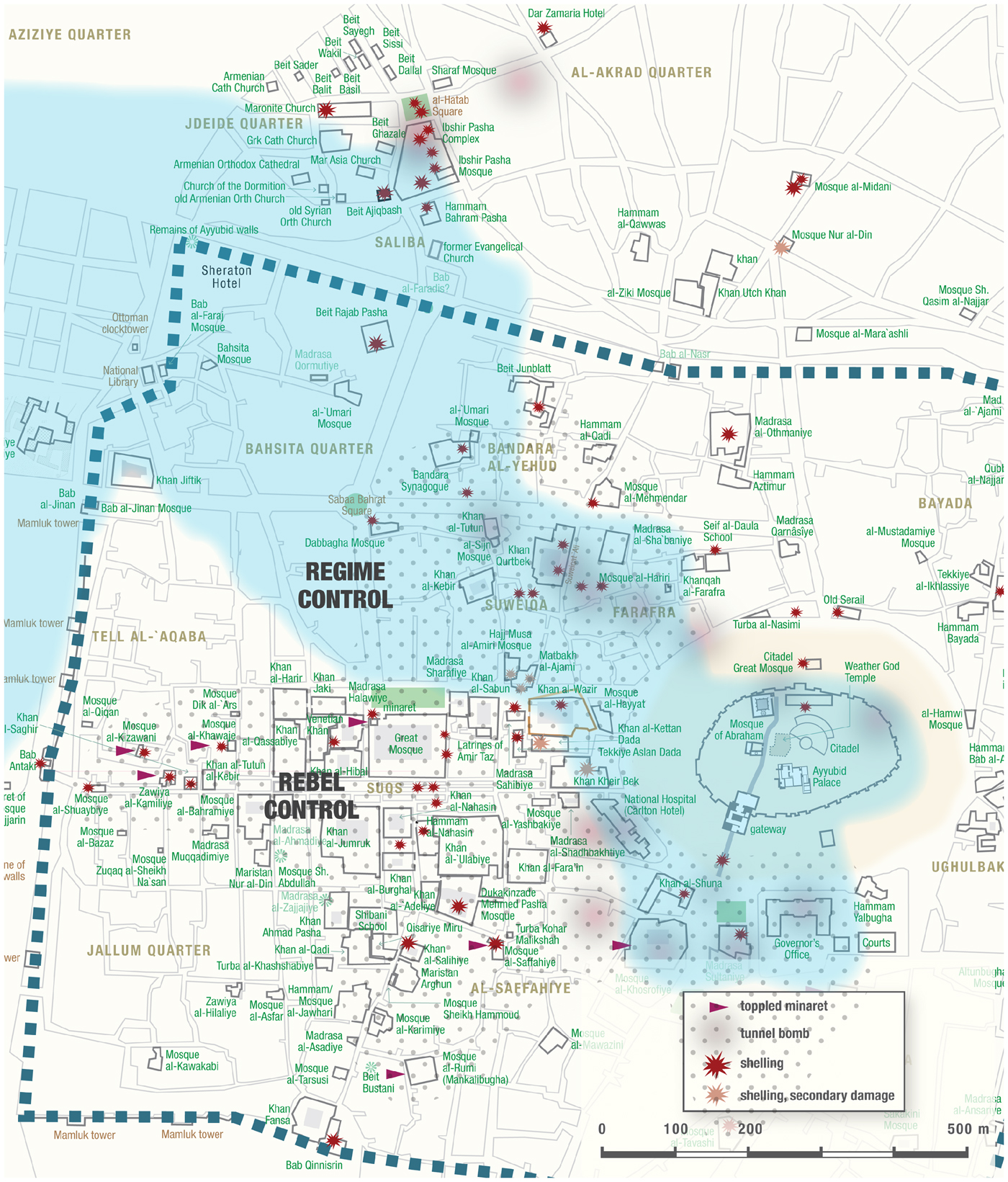

Figure 1. Map of the central historic zone of Aleppo showing locations of intense shelling and tunnel bombs pre-2017. The blue zone indicates control by government forces, red blurred circles indicate tunnel-bombed areas, red flashes show severe rocket damage, and red triangles indicate damaged minarets. Image by Ross Burns, 2017.

While Aleppo took fifteen months before rising in opposition to the central government, the war quickly settled into a pattern of intensity probably unmatched by any of the historic Syrian cities. The lines of confrontation were shaped by the central position of the Citadel, which consistently remained in government hands. The opposition forces adopted positions along the southern perimeter of the Citadel, spreading west into the main area of souks clustered around the Great Mosque, originally a work of the early Islamic dynasty, the Umayyads. Intense fighting took place, with the opposition forces adopting firing points in many of the historic mosques and their minarets and the government forces using artillery and tanks to attempt to regain the central area. A fierce blaze swept through the souks after an electricity substation caught fire, gutting many of the historic khans and madrasas and reaching one wing of the Great Mosque and its minaret.Footnote 18

During these months of exchanges, some of the most significant buildings of the Medina area were badly damaged. The minarets chosen as firing positions by opposition forces were particularly badly hit, given their prominence and relatively vulnerable structures. The minaret of the Great Mosque was the worst casualty, possibly felled by conventional artillery or deliberate explosion from within.

Figure 2. The Seljuk-period minaret of the Great Mosque in Aleppo. Photograph by Ross Burns, 2005.

Not only was the minaret an emblematic centrepiece of the city, but it was also a monument of incomparable historical value as it was the only building surviving from the period of Seljuk rule in late eleventh-century northern Syria. As such, it gave us our only glimpse of the rich blend of traditions that were present in the area at the time.

While the pattern of historic monuments becoming victims of intense fighting, with each side seeking tactical advantage, is a familiar risk in warfare, the Syrian conflict went on to introduce a new benchmark in mindless destruction. The savage use of explosive power intentionally to topple historic buildings was introduced to the Syrian theatre by Islamic Front, a militia grouping backed by outside Sunni interests, who initiated a series of eleven tunnel bombs around the Citadel and along the approaches from the northwest. Around the southern perimeter of the Citadel, some of the most precious buildings of the Ayyubid and Ottoman eras were destroyed by tunnelling beneath them, filling the excavated spaces with explosives and setting off massive blasts that virtually sucked the remains of once-solid buildings into a crater, leaving little more than piles of dust. The tunnel-bomb explosions are mapped in Figure 1 as blurred red circles. There can be few more telling examples in modern times of the use of explosives deliberately to efface historic buildings for ends which are virtually pointless in military terms. The fact that most of these explosions were claimed by an organization funded to support the cause of Islam is particularly bewildering.Footnote 19 Perhaps equally puzzling is the fact that it seems this series of destructive acts attracted nothing like the level of condemnation outside Syria which the campaign of destruction by the Islamic State armed group would soon attract.

Figure 3. Plan of Palmyra. Red markers indicate monuments destroyed or heavily damaged. Image by Ross Burns, 2017.

Palmyra

In 2015, Islamic State varied the formula for the use of monuments in a “shock and awe”Footnote 20 campaign by putting considerable effort into attracting maximum “credit” for its destructive achievements using video clips, posted images and even a glossy monthly English-language magazine, Dabiq, now defunct. IS heralded its arrival by targeting Islamic sites, then ranging further to explore two apparent objectives: to destroy sites associated with the commemoration of the dead, and to eliminate buildings from pre-Islamic cultures, a choice not confined to those displaying human figures.Footnote 21

After graduating from simple, rural Islamic “saints' tombs”, IS perfected the art of gaining the attention of an audience by targeting solid structures of immense historical significance, beginning with the detonation of the small but richly decorated Temple of Baalshamin in Palmyra. The more publicity such blasts yielded, the more it seemed to encourage IS to move on to even more impressive targets. The IS blast experts even managed to destroy the towering walls of the central cella of the Temple of Bel, largely reducing it to powder and heaps of rubble.Footnote 22

Figure 4. Central shrine (cella) of the Temple of Bel, 2004. Photograph by Ross Burns.

Moving on, IS carefully selected for toppling twelve of the most intact of the Roman-era tower tombs that bordered the oasis on the west, and hammered most of the facial features from the remaining limestone reliefs and busts on the walls of the Palmyra Museum.Footnote 23 The relatively open structure of the oasis's famed Monumental Arch required two attempts to topple it and even then most of the outer pylons survived the blasts. During its brief retaking of Palmyra in early 2017, IS took on the city's great Tetrapylon and the Roman-era theatre, both major features along the city's striking colonnaded axis. Also open structures, both were harder targets, but IS succeeded in bringing down twelve of the sixteen columns of the Tetrapylon's majestic structure.Footnote 24

Writing off Syria's monuments?

A common set of assumptions, reflected to some extent in Western media coverage of these campaigns of destruction,Footnote 25 is that little is left of Syria's ancient and Islamic remains, that most damage is terminal and that few monuments are under effective Syrian care. However, on all three counts, especially the last, nothing could be further from the truth.

Syria is so rich in remains, particularly in the areas west of the country's main north–south transport axis, that it still presents an unrivalled range of treasures. Shortly after the current conflict began, this author sought to counter the impression that Syria's past was a write-off, perhaps best forgotten, and to that end he set up a website, entitled The Monuments of Syria, to give a visual complement to the text of his study of Syria's archaeological treasures.Footnote 26 The idea was to show people how much was at stake. Increasingly, this author was concerned at the number of media reports (often uncritically re-endorsed through social media)Footnote 27 that gave the impression that massive structures such as the great Hospitaller castle, Krak des Chevaliers, might have been “destroyed”.

Figure 5. Southern inner defences of Krak des Chevaliers, 1998. Photograph by Ross Burns.

In fact, damage from several bouts of shelling seems confined to a few fairly limited sections – for example, one or two crenellations on top of a tower or a part of a tower wall section, and, most regrettably, some of the fine Gothic-style tracery on the portico of the knights’ Great Hall.Footnote 28 In general, the overall structure of monuments like the Krak is as capable today of withstanding a few mortar shells as when it withstood the mangonels of Baybars in the late thirteenth century (when its Crusader defenders gave up not because they had lost the protection of their fortified walls but because they had run out of manpower and supplies). Often claims of extensive damage were supported by photos that showed the structures to be in the same condition as they had been in prior to 2011, as seen in this author's own photo resources.Footnote 29 The wear and tear of the centuries has often been misinterpreted as damage from hostilities in the civil war.

Attempting a damage tally

Two years into the conflict, this author began to produce from his own database a running tally of damage where it could be verified from posted images,Footnote 30 accompanied by an assessment (based purely on visual evidence, not verbal descriptions) of the degree of damage as it related to the possibility of restoring the remains. It should be emphasized that these conclusions have been reached only through examination of visual evidence from posted photo material, so they necessarily represent a selective account of the extent of the damage. While such visual comparison cannot replace an on-the-spot report by a structural engineer, the attempt at a provisional tally in relation to Aleppo and Palmyra is reproduced in Figure 6, with the second column recording the national total of sites or buildings in each category.Footnote 31 The figures question to some extent the estimate often given in social media or commentary on the extent of the damage. Though the figures (broken down between national cases and with sub-categories for Aleppo and Palmyra) include a number of high-profile cases of deliberate or large-scale destruction, the last two categories of verified cases involve minor or at least non-structural damage which could be repaired.

Figure 6. Table of damage estimates for March 2017, with breakdown for Aleppo and Palmyra.

It should also be noted that levels of destruction vary greatly from site to site given the sporadic pattern of fighting in many areas and the difficulties all sides have had in retaining territory. In the third and fourth columns of Figure 6, the figures for Palmyra and Aleppo show that the two locations combined account for around 40% of total cases in the national count (ninety-eight out of 250). But between Aleppo and Palmyra, the severity of the damage at the two sites shows different patterns.

Aleppo was exposed to the slow grind of a conflict that continued for over four years across its historic city centre until its fall to government forces in December 2016, with the front lines hardly moving in that time. By contrast, the campaign of destruction at Palmyra by IS was more deliberate and ruthless, and was over more quickly. The Palmyra damage list, at twenty-seven in total, contains many fewer buildings than the seventy-one recorded at Aleppo.Footnote 32 However, because of the small number of structures there, Palmyra suffered the loss of around the same percentage of its historic remains on the casualty list. The cases of destruction at Palmyra were more numerous in category 1 (near or total loss); the detonations were more thoroughly effective in a short period of time but did not result in extensive secondary damage to other buildings. Aleppo, however, accounts for something like 35% of the cases recorded nationwide in categories 2 and 3 (damage short of structural loss), with military activity spread across a large percentage of the walled city.

An archaeological wasteland?

These two cases, Aleppo and Palmyra, illustrate part of the overall pattern of destruction that has spread across much of the country east of the Orontes Valley, with well over 200 major buildings or sites damaged or destroyed over the past six years of conflict. To many in the outside world, the impression is that Syria's past is a wasteland – ironically this image has been imprinted on people's minds more through the repeated video footage of collapsed modern civilian housing, especially in east Aleppo. As the area of historic monuments was rarely directly accessible by foreign journalists coming via rebel-held areas to the north and east, the impression might have arisen that all of Aleppo resembles the burnt-out wasteland of the eastern suburbs.

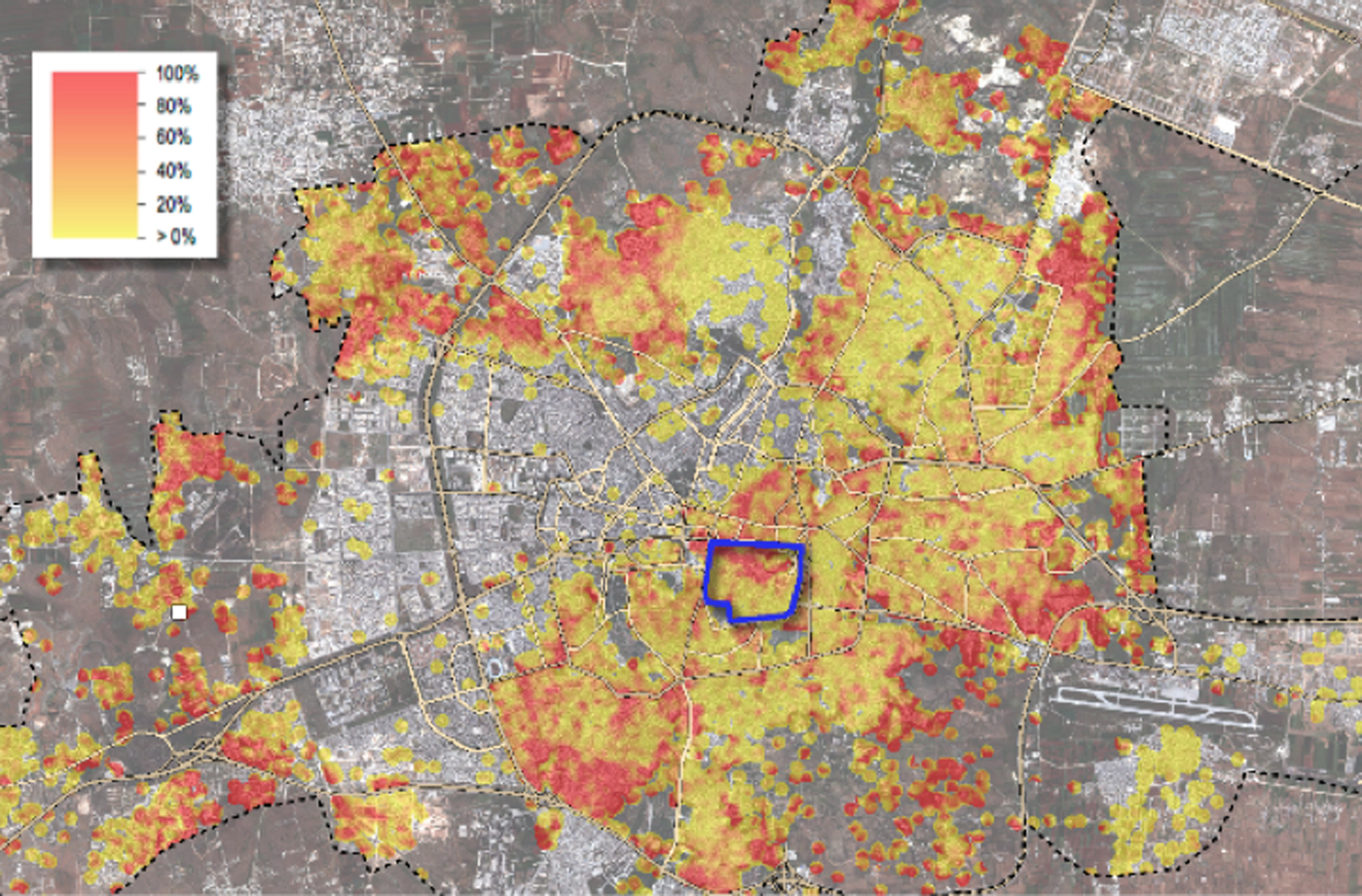

If the conflict is ever to wind down to a stable future, the risk of writing off Syria's status as a cultural treasure trove might perhaps be the worst legacy the outside world could provide. Often this is done in the most well-meaning way, but it reinforces assumptions that there is little or nothing left to serve as a basis for reconstruction. While this is true of many areas of devastated modern housing more often exposed, for example, to area bombardment (see Figure 7), the conclusion doesn't necessarily apply to the remains of the past that are less often adopted by civilians as refuges.

Figure 7. UNOSAT satellite image of Aleppo with walled city in blue box. Scale shows intensity of destruction, mainly in areas of modern housing. Image by Ross Burns, January 2017. Also see: https://tinyurl.com/y8ynexdw.

Moreover, it is somewhat concerning that many well-intentioned outsiders, assuming that much of Syria's past is lost, envisage a future for Syria's heritage in the world of 3D animation or scaled-down reproductions generated by expensive technological processes carried out abroad. Any future for a regenerated tourism industry in a post-conflict Syria must lie with Syrians fully engaged in the process, whether as experts and engineers or as bus drivers, waiters, guides and curators. This means homes must be restored or rebuilt, and refugees encouraged to return and rebuild. The old quarries that once supplied the honeycomb-textured stone of Palmyra or the crystalline columns of Apamea can then be activated again, with Syrian masons and engineers doing what their predecessors have done over 2,000 years. It will take time, and will involve retraining, restoration of services and an environment of security. For Palmyra it will require the bringing back to life of Tadmor, the modern town alongside Palmyra that once supplied all the services and support staff needed. To envisage Syria's reconstruction in any other way – for example, as a new employment opportunity for experts abroad – is not only misguided; it is wrong.

Contributions from outside, however, would make sense if they were to aid in this process of harnessing the skills and commitment of Syrians and were supervised through UNESCO, which itself has no capacity to provide funding. For example, those institutions abroad that have long housed finds from Syrian expeditions, either in museums or in research institutions, could ensure that this material is fully digitized and freely available not only to researchers but to the interested public, including Syrians. The best form of direct assistance for the work to be done in Syria might be in the form of training in modern techniques and materials for restoration, along the lines, for example, of the work that several Italian teams have quietly been doing in the Middle East for some years to restore wall paintings and mosaics. In this respect, computerized modelling of buildings could inform the physical restoration of structures in Syria by enabling engineers and builders to best understand how structures could be rebuilt using as much of the original materials as possible. But 3D imaging is not an end in itself. It is a step on the path to bringing monuments back to life – in Syria, not in Trafalgar Square or downtown Manhattan.Footnote 33

Some foreign experts have preferred to express their opposition to reconstruction altogether, arguing that the phases of damage and even the total collapse of a building are part of its “story”.Footnote 34 This, too, is misguided. Where buildings can be reassembled from their rubble, they should be made intelligible to a wider audience. We should also recall that a high proportion of Syria's great monuments have been reconstructed, restored or patched up, either over the centuries or more often in the past century. Much of Palmyra, for example, had already been put back together after centuries of earthquakes and destructive interventions. Buildings such as the Temple of Bel were carefully restored to ensure their future stability. It is worth noting that although much of the building's cella was virtually turned to dust by the explosive charges laid by IS in 2016, the most heavily restored part, the great towering entrance doorway in the western colonnade of the central shrine, still stands proud. It was reinforced with steel following the French detailed study of the temple in 1929–32.Footnote 35

The records of researchers of the past can also present significant resources to help us understand how buildings, now toppled, worked structurally. It may be no coincidence that virtually all the Palmyrene tombs, temples and monuments savagely reduced to dust by IS in 2016 were carefully studied by archaeological research teams over recent decades. The teams’ publications and their archives have often left us stone-by-stone records of buildings. The way to offer insights into the rich layering of cultures Syria provides is to use this documentary trail to take what stones have survived the destructive urges of the present and use them as a basis to fill in the gaps. It is a painstaking task, requiring years of dedicated work, but it has been done before – for example, with the Dresden Frauenkirche after the bombing raids of 1944.Footnote 36 Without reconstruction programmes, too, sites such as the great avenue of columns stretching across Apamea in the Orontes Valley would largely comprise tumbled column drums hidden in the grass. Syrians deserve to know how splendid a past their country presented to the world, just as, for example, one of the first reconstruction projects of post-Civil War Lebanon in the early 1990s was the National Museum, superbly brought back to life and with a high proportion of its exhibits recovered from safe storage locations, many years after they were assumed destroyed or lost.Footnote 37

Other institutions reinforce UNESCO's central role in such efforts to safeguard monuments, particularly those inscribed by member countries on the World Heritage list. The pre-2011 record of organizations such as the Aga Khan Trust for Culture has been remarkable in restoring some of Syria's major Islamic buildings.Footnote 38 The International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) harnesses non-governmental expertise in the field of reconstruction, respecting the authenticity of a monument, and promotes the application of theory, methodology and scientific techniques to that end. Rules have long been drawn up to guide reconstruction programmes such as the Venice Charter of 1964–2004.Footnote 39 In many UNESCO member countries there is an inherent tension between “dirt archaeologists” and experts intent on preserving the integrity of their evidence, on the one hand, and the local authorities responsible for presenting sites to make them more accessible and comprehensible to visitors. Syria has so far managed to avoid the “Disneyfication” of sites that has taken place in other countries, where authenticity has been sacrificed for tourism or commercial ends.

At the time of completing this article, the conflict in Syria has begun to wind down, hopefully reducing the level of risk to the country's population and the monuments which record their great heritage. Some pockets of rebel control remain, parts of the country remain under occupation by foreign forces, and a workable programme for the repatriation of civilians to their homes has yet to be undertaken. It may not, however, be premature to think about reconstruction in areas that are no longer contested, though at the moment the terms for external aid to the reconstruction process remain controversial.Footnote 40

A proper inventory of sites and degree of damage will be a starting point, a project already being undertaken by the DGAM.Footnote 41 It will take decades to complete any schedule of regeneration, but a good start could be made by selecting some of the key monuments that could encourage the reawakening of civic pride and eventually of the tourism industry. In many areas, local civic groups or authorities are repairing mosques, and such landmark buildings as the Aleppo Great Mosque's minaret are now being studied and viable remains rescued from the rubble and sorted.Footnote 42

The worst outcome would be the belief that Syria's past is lost. We need to resist such assumptions, and we should also avoid encouraging illusions that the country's monuments can be revived in such “here-today-gone tomorrow” palliatives as 3D printed facsimiles or virtual-reality reconstructions. It was the whole context – the countryside, the people, their openness and generosity, the food and the experience of seeing a site like Palmyra come to life as shadows crept across its tapestry of centuries – that made Syria memorable. We shouldn't settle for less. We owe that to the Syrians.

Figure 8. Palmyra seen from Qalaat Shirkuh at the approach of sunset. Photograph by Ross Burns, April 2011.