Obesity and overweight among children and youth is an important public health issue( 1 ). In Europe, between 9·4 and 26·4 % of boys and between 6·4 and 15·9 % of girls aged 10–15 years are overweight or obese( Reference Ahluwalia, Dalmasso and Rasmussen 2 ). In the USA, among adolescents aged 12–19 years, 20·5 % are obese and obesity rates are slightly higher among females (21·0 %) compared with males (20·1 %)( Reference Ogden, Carroll and Lawman 3 ). In Canada, 30·1 % of adolescents aged 12–17 years are overweight or obese( Reference Roberts, Shields and de Groh 4 ), which predisposes them to future chronic diseases( 5 ). To address the obesity problem, the WHO recently issued new recommendations encouraging populations of all ages to limit sugar intake, including sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB), to no more than 10 % and possibly 5 % of total energy intake( 6 ).

SSB consumption contributes to excessive intake of sugar among adolescents, which is related to many health problems such as heart diseases( Reference Yang, Zhang and Gregg 7 – Reference Malik, Popkin and Bray 10 ), stroke( Reference Yang, Zhang and Gregg 7 ), obesity( Reference Bray, Nielsen and Popkin 11 – Reference Olsen and Heitmann 16 ), type 2 diabetes( Reference Cozma, Sievenpiper and de Souza 17 – Reference Malik, Popkin and Bray 20 ), hypercholesterolaemia( Reference Sievenpiper, Carleton and Chatha 21 , Reference Welsh, Sharma and Abramson 22 ), cancer( Reference Larsson, Bergkvist and Wolk 23 ) and tooth decay( Reference Moynihan and Kelly 24 ). Moreover, SSB offer no health benefits, increase total energy intake and may reduce the consumption of foods containing essential nutrients for optimal health, such as milk( 6 , 25 ). Unfortunately, adolescents are large consumers of SSB. SBB are the main source of energy from all beverages in adolescents aged 13–18 years in London, UK( Reference Ng, Ni Mhurchu and Jebb 26 ). They are also the main sources of added sugar in Mexico, representing 66·2 % of added sugars for adolescents from 12 to 19 years of age( Reference Sanchez-Pimienta, Batis and Lutter 27 ). In the USA, adolescents aged 13–18 years drink an average of 606 ml of soda and fruit drinks daily( Reference Popkin 28 ). In Canada, boys aged 14–18 years drink a mean quantity of 574 g (which equates approximately the same in millilitres) of SSB daily and girls 354 g daily( Reference Garriguet 29 ).

Since habits developed during adolescence tend to be preserved throughout life( 1 ), it is essential to promote healthy behaviours among this population in a growing search for autonomy, especially in their food and drink choices( Reference Breinbauer and Maddaleno 30 , Reference Baril, Paquette and Ouimet 31 ). Although the family environment is largely responsible for the development of healthy habits among children and youth, the responsibility of the school environment should not be underestimated given the time spent at school( Reference Flynn, McNeil and Maloff 32 , 33 ). In fact, school is the ideal setting to develop and promote healthy eating habits among children and adolescents( Reference Flynn, McNeil and Maloff 32 , Reference Story, Neumark-Sztainer and French 34 – Reference Casey and Crumley 36 ). Additionally, schools offer the opportunity to easily reach young people, regardless of their age, socio-economic status (SES), cultural background and ethnicity( Reference Flynn, McNeil and Maloff 32 , Reference Bandura 37 , Reference Jones, Lynch and Kass 38 ).

In the field of public health, ecological models are commonly used to design interventions aimed at changing health behaviours( Reference Sallis, Owen and Fisher 39 ), such as decreasing SSB consumption among adolescents. One characteristic of these models is that they recommend targeting both individuals and their environment to increase the chances of successfully changing health behaviours( Reference Sallis, Owen and Fisher 39 ). For example, an intervention could target adolescents by giving them information on the negative health consequences associated with consuming SSB and also target their environment by removing SSB from the vending machines and the cafeteria at their school.

Some authors recommend using theory to develop interventions that have a greater chance of changing health behaviours( Reference Baranowski, Lin and Wetter 40 – Reference Rothman 45 ). The theories most commonly used to develop public health interventions originate from social psychology (i.e. psychosocial theories) and include the Social Cognitive Theory (SCT)( Reference Bandura 46 ) and its predecessor by the same author, the Social Learning Theory (SLT)( Reference Bandura 47 ), the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB)( Reference Ajzen 48 ), the Transtheoretical Model (TTM)( Reference Prochaska and DiClemente 49 ) and the Self-Determination Theory (SDT)( Reference Ryan and Deci 50 ). Explaining each of these theories is beyond the scope of the present review. However, each theory gives indications on what needs to be changed in order to get individuals to intend or be motivated to change their behaviour. For example, the SCT/SLT both suggest that changing people’s perception of their ability to change their behaviour – a notion known as self-efficacy – is one way to get them to change their behaviour. One advantage of the use of theory in designing public health interventions is that it can guide which techniques should be used to get participants to change their behaviour( Reference Michie, Johnston and Francis 51 , Reference Abraham and Michie 52 ). For example, the taxonomy of Cane et al.( Reference Cane, Richardson and Johnston 53 ) contains eighty-seven different behaviour change techniques originating from diverse theories that can be used to change health behaviours. There is also recent work that aims to link these behaviour change techniques to their own mechanisms of action to facilitate the development and evaluation of behaviour change interventions( Reference Michie, Carey and Johnston 54 ).

In order to develop or improve school-based interventions aimed at decreasing SSB intake among adolescents, it is essential beforehand to review the scientific literature to identify which interventions and behaviour change techniques are effective at promoting this behaviour among this population. A number of reviews on various topics related to SSB and children or adolescents have already been conducted. The majority of previous reviews have focused on associations between SSB consumption and adverse health effects among children and adolescents( Reference Ali, Rehman and Babayan 55 ), such as increased body weight( Reference Forshee, Anderson and Storey 56 – Reference Keller and Bucher Della Torre 59 ), and also on the methodological qualities of those reviews( Reference Bucher Della Torre, Keller and Laure Depeyre 60 , Reference Weed, Althuis and Mink 61 ). One study reviewed methods to assess intake of SSB in adults, adolescents and children( Reference Riordan, Ryan and Perry 62 ). A few studies have reviewed the impact of policies( Reference Levy, Friend and Wang 63 ) and additional taxes( Reference Powell, Chriqui and Khan 64 , Reference Cabrera Escobar, Veerman and Tollman 65 ) on children’s and adolescents’ consumption of SSB. Finally, there are a number of published reviews on interventions to reduce SSB consumption in children and adolescents( Reference Avery, Bostock and McCullough 66 , Reference Lane, Porter and Estabrooks 67 ), including school-based interventions( Reference Tipton 68 ), or to prevent childhood and adolescent obesity( Reference Sharma 69 ). However, those existing reviews did not specifically target adolescents, and also included children( Reference Avery, Bostock and McCullough 66 – Reference Sharma 69 ), and none of them assessed the behaviour change techniques used to decrease SSB consumption.

The aim of the present study was to fill this gap in the literature by performing a systematic review of school-based interventions aimed at reducing SSB consumption among adolescents aged 12–17 years. A second objective was to identify the behaviour change techniques most effective at decreasing SSB consumption using the taxonomy of Cane et al.( Reference Cane, Richardson and Johnston 53 ) in order to inform future school-based interventions aimed at changing this behaviour among adolescents.

Methods

The study protocol was registered in PROSPERO (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/) by Do.B. in May 2015 (no. 42015023582).

Study eligibility criteria

Population

Adolescents were defined as individuals between the ages of 12 and 17 years. Studies including participants aged <12 years or >17 years were included only if ≥80 % of the participants were individuals between the ages of 12 and 17 years or if the mean age was between these ages.

Intervention

To be considered school-based, interventions had to be carried out in a school setting or the authors had to refer to their intervention as school-based. Studies evaluating the impact of school nutrition policies were included. Community-based interventions or those carried out outside schools were not included in the review.

Outcome

Articles had to report information on individual SSB consumption to be included in the review. There were no criteria on how individual consumption of SSB needed to be reported in the articles (e.g. millilitres or number of glasses per day or per week, percentage of individuals who reported consuming a given quantity of SSB, etc.). SBB included regular (non-diet) soft drinks, fruit drinks (excluding 100 % pure fruit juices), energy drinks, sports drinks, sweetened tea and coffee (iced or hot) and other beverages with added sugar (e.g. slush)( 70 ). There were also no criteria on how studies that included multiple types of beverages in their SSB definition needed to report this outcome; it could be reported separately (e.g. soft drinks, fruit drinks, etc.) or collectively (i.e. for all SSB). Studies whose definition of SSB included 100 % pure fruit juices were not included in the review, except if this information was presented separately from other SBB. When unsure about whether or not SBB included 100 % pure fruit juices, the authors of the articles were personally contacted by Do.B. Studies reporting information on SSB availability or SSB sales in schools were not included, since they are not measures of individual consumption of SSB.

Study designs

Types of study design included were randomised controlled trials (RCT), quasi-experimental studies and one-group pre–post studies.

Exclusion criteria

Articles written in languages other than English or French were excluded. Qualitative studies were also excluded given that the objective was to perform a meta-analysis of the results of interventions.

Search strategy

The following databases were investigated: MEDLINE/PubMed (1950+), PsycINFO (1806+), CINAHL (1982+) and EMBASE (1974+). Proquest Dissertations and Theses (1861+) was also investigated for grey literature (i.e. unpublished trials). There was no restriction on the year of publication of the articles. The search was performed by L.-A.V.-I. on 2 July 2015 and was updated by the same author on 21 December 2016 to include articles published until 1 December 2016. In each database, the search strategy included terms related to three major themes: SSB, adolescents and school interventions (see the online supplementary material, Supplemental File 1, for the complete search strategy). The search was developed with an experienced librarian. Additional studies were included by checking the references of the articles included in the systematic review (i.e. secondary references).

Study selection and data extraction

All articles were first screened by L.-A.V.-I. for possible duplicates and then according to their title and abstract (see Fig. 1). Clearly irrelevant articles were excluded at this step. The remaining articles were fully retrieved (full text) and two authors (L.-A.V.-I. and Do.B.) independently assessed them for eligibility. A few studies reported results based on the same sample and/or the same intervention. To avoid duplication of results and attributing more weight to these studies, only the study that had the best methodological qualities (e.g. RCT with bigger sample size v. one-group pre–post pilot study) and that reported the most information (e.g. baseline, post-test and follow-up data v. baseline and post-test data only) was included for further analysis.

Fig. 1 PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flowchart( Reference Moher, Liberati and Tetzlaff 134 ) showing selection of the studies included in the present systematic review (SSB, sugar-sweetened beverage)

Data were extracted independently by two reviewers (L.-A.V.-I. and Do.B., A.B.-G., Da.B., C.S. or M.D.Footnote *) using a standardised data extraction form. Data extracted included information on the study population, intervention, types of SSB included in the study and their measure, use of theory, behaviour change techniques used and results of the intervention. Interventions were classified as educational/behavioural and/or legislative/environmental depending on whether they targeted individuals (e.g. nutritional education on SSB) or their environment (e.g. ban on SSB in schools) or both. The quality of studies was assessed using the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Study of the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP)( Reference Armijo-Olivo, Stiles and Hagen 71 ). This tool, recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration( Reference Higgins and Green 72 ), was selected because it can be used for different kinds of quantitative study design (RCT, one-group pre–post, etc.) and because it is especially formulated for public health studies. Briefly, the EPHPP tool evaluates the quality of studies using the following six criteria: (i) selection bias; (ii) study design; (iii) confounders; (iv) blinding; (v) data collection method; and (vi) withdrawals and dropouts. The rating for each of the six components is used to obtain a global rating of a study’s quality. A strong global rating is obtained when there are no weak ratings to any of the six components of the EPHPP. A moderate global rating is obtained when there is one weak rating and a weak global rating when there are two or more weak ratings( Reference Armijo-Olivo, Stiles and Hagen 71 ). Behaviour change techniques used in interventions were classified according to the taxonomy of Cane et al.( Reference Cane, Richardson and Johnston 53 ) which contains eighty-seven different behaviour change techniques (e.g. restructuring the physical environment, behavioural goal setting, self-monitoring of behaviour, etc; see online supplementary material, Supplemental File 2, for the complete list of behaviour change techniques). Disagreements at each step were resolved by discussion and when no consensus could be reached a third reviewer (Do.B. or A.B.-G., depending on who originally performed the second data extraction) helped resolve the discrepancy.

Results

The results of the search strategy and its update are presented in Fig. 1. A total of thirty-six studies detailing thirty-six independent interventions were included in the present systematic review (see Table 1). This represented a total of 152 001 participants at baseline. Seventy-five per cent of studies were conducted in North America (USA: twenty-four studies( Reference Jones, Lynch and Kass 38 , Reference Bauhoff 73 – Reference Nanney, MacLehose and Kubik 95 ); Canada: three studies( Reference Lo, Coles and Humbert 96 – Reference McGoldrick 98 )). Two studies were conducted in Australia( Reference Collins, Dewar and Schumacher 99 , Reference Smith, Morgan and Plotnikoff 100 ) and another two in Belgium( Reference Dubuy, De Cocker and De Bourdeaudhuij 101 , Reference Haerens, Deforche and Maes 102 ). Finally, one study was conducted in each of the following countries: Brazil( Reference da Silva Vargas, Sichieri and Sandre-Pereira 103 ), China( Reference Wing, Chan and Yu 104 ), India( Reference Singhal, Misra and Shah 105 ), Korea( Reference Bae, Kim and Kim 106 ) and The Netherlands( Reference Yildirim, Singh and te Velde 107 ). Given the important heterogeneity observed between the studies (i.e. differences in populations, study designs, types of intervention, behaviour change techniques used, behavioural measures and type of SSB included), no meta-analyses of the results were performed. In the rest of the text, the letter k will be used to represent the number of studies and the letter n to represent the number of participants.

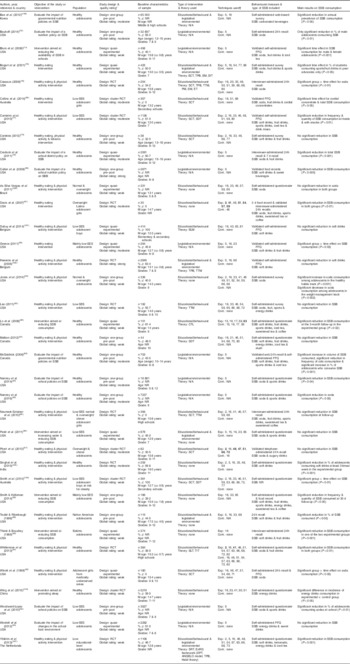

Table 1 Summary of the studies included in the present systematic review

SSB, sugar-sweetened beverage; SES, socio-economic status; RCT, randomised controlled trial; n, number of participants; ♂, male students; NR, not reported; M, mean; N/A, not applicable; SCT, Social Cognitive Theory; TPB, Theory of Planned Behaviour; EM, Ecological Model; DIT, Diffusion Innovation Theory; TTM, Transtheoretical Model; PM, Proactive Model; SM, Solution Model; ET, Empowerment Theory; SDT, Self-Determination Theory; ELM, Elaboration Likelihood Model; CTL, Constructivist Theory of Learning; SLT, Social Learning Theory; TIT, Theory of Interactive Technology; SRT, Self-Regulation Theory; EnRG, Environmental Research framework for weight Gain prevention; DPT, Dual-Process Theory; ANGELO, ANalysis Grid for Environments Linked to Obesity; Exp., experimental group; Cont., control group.

* Global rating of the quality of studies was performed using the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies( Reference Armijo-Olivo, Stiles and Hagen 71 ).

† The numbers refer to those used in the Behaviour Change Technique Taxonomy of Cane et al.( Reference Cane, Richardson and Johnston 53 ) (listed in online supplementary material, Supplemental File 2) and in cases where there is an active control group, differencing techniques are presented in bold font.

Characteristics of interventions

Close to 60 % of interventions (58·3 %, k 21) included were aimed at reducing SSB consumption as part of a general objective: the promotion of healthy eating and physical activity combined (k 17)( Reference Jones, Lynch and Kass 38 , Reference Casazza 76 – Reference Cordeira 78 , Reference Lao 83 , Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Friend and Flattum 85 , Reference Pbert, Druker and Gapinski 87 , Reference Teufel and Ritenbaugh 89 , Reference Whittemore, Jeon and Grey 91 , Reference Winett, Roodman and Winett 92 , Reference Malbon 97 , Reference Smith, Morgan and Plotnikoff 100 – Reference da Silva Vargas, Sichieri and Sandre-Pereira 103 , Reference Singhal, Misra and Shah 105 , Reference Yildirim, Singh and te Velde 107 ) or healthy eating alone (k 4)( Reference Bogart, Elliott and Uyeda 75 , Reference Davis, Ventura and Alexander 81 , Reference Greece 82 , Reference Collins, Dewar and Schumacher 99 ). One study also included tobacco prevention( Reference Cordeira 78 ). Ten interventions (27·8 %) had the objective of evaluating the impact of nutrition policies in schools or changes in the school environment, such as reduced availability of SSB( Reference Bauhoff 73 , Reference Blum, Davee and Beaudoin 74 , Reference Cradock, McHugh and Mont-Ferguson 79 , Reference Cullen, Watson and Zakeri 80 , Reference Nanney, Maclehose and Kubik 84 , Reference Woodward-Lopez, Gosliner and Samuels 93 – Reference Nanney, MacLehose and Kubik 95 , Reference McGoldrick 98 , Reference Bae, Kim and Kim 106 ). Only four interventions (11·1 %) were specifically aimed at reducing SSB consumption and increasing water consumption( Reference Patel, Bogart and Elliott 86 , Reference Smith and Holloman 88 , Reference Thiele and Boushey 90 , Reference Lo, Coles and Humbert 96 ). Finally, one intervention was aimed at promoting sleep and included reducing energy drinks consumption as a means of achieving this goal( Reference Wing, Chan and Yu 104 ).

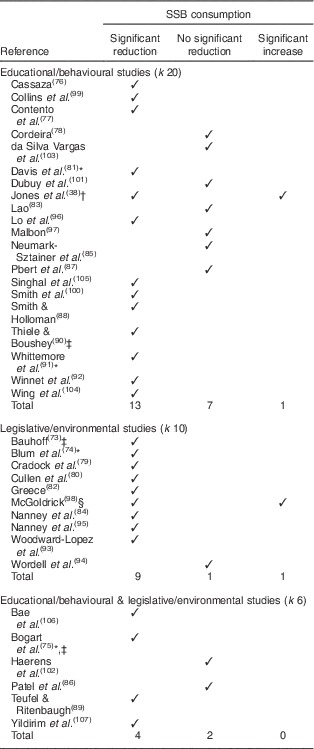

Twenty interventions (55·6 %) were classified as educational/behavioural( Reference Jones, Lynch and Kass 38 , Reference Casazza 76 – Reference Cordeira 78 , Reference Davis, Ventura and Alexander 81 , Reference Lao 83 , Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Friend and Flattum 85 , Reference Pbert, Druker and Gapinski 87 , Reference Smith and Holloman 88 , Reference Thiele and Boushey 90 – Reference Winett, Roodman and Winett 92 , Reference Lo, Coles and Humbert 96 , Reference Malbon 97 , Reference Collins, Dewar and Schumacher 99 – Reference Dubuy, De Cocker and De Bourdeaudhuij 101 , Reference da Silva Vargas, Sichieri and Sandre-Pereira 103 – Reference Singhal, Misra and Shah 105 ), while all the studies on school policies and environmental changes (k 10) were classified as legislative/environmental interventions( Reference Jones, Lynch and Kass 38 , Reference Bauhoff 73 , Reference Blum, Davee and Beaudoin 74 , Reference Cradock, McHugh and Mont-Ferguson 79 , Reference Cullen, Watson and Zakeri 80 , Reference Nanney, Maclehose and Kubik 84 , Reference Woodward-Lopez, Gosliner and Samuels 93 – Reference Nanney, MacLehose and Kubik 95 , Reference McGoldrick 98 ) (see Table 2). Only six interventions (16·7 %) included both an educational/behavioural component and a legislative/environmental component( Reference Bogart, Elliott and Uyeda 75 , Reference Patel, Bogart and Elliott 86 , Reference Teufel and Ritenbaugh 89 , Reference Haerens, Deforche and Maes 102 , Reference Bae, Kim and Kim 106 , Reference Yildirim, Singh and te Velde 107 ).

Table 2 Efficacy of interventions included in the present systematic review according to their type

SSB, sugar-sweetened beverage; k, number of studies.

* Significant time effect only or significant reduction of SSB consumption in both the experimental and the control group.

† Significant reduction of SSB consumption in half of the experimental group (peer advocates) and significant increase of SSB consumption in the other half of the experimental group (non-peer advocates).

‡ Significant reduction of SSB consumption in half of the experimental group and no significant reduction of SSB consumption in the other half of the experimental group.

§ Significant reduction in frequency of cola consumption, but significant increases in volume of SBB consumed and in percentage of adolescents who consume SSB.

Characteristics of participants

About half of the interventions (47·2 %, k 17) were conducted among healthy adolescents( Reference Bauhoff 73 – Reference Casazza 76 , Reference Cordeira 78 – Reference Cullen, Watson and Zakeri 80 , Reference Nanney, Maclehose and Kubik 84 , Reference Whittemore, Jeon and Grey 91 , Reference Nanney, MacLehose and Kubik 95 – Reference McGoldrick 98 , Reference Haerens, Deforche and Maes 102 , Reference Wing, Chan and Yu 104 – Reference Bae, Kim and Kim 106 ). Thirteen studies (36·1 %) targeted adolescents whose parents had a low SES( Reference Jones, Lynch and Kass 38 , Reference Contento, Koch and Lee 77 , Reference Greece 82 , Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Friend and Flattum 85 , Reference Patel, Bogart and Elliott 86 , Reference Smith and Holloman 88 , Reference Woodward-Lopez, Gosliner and Samuels 93 , Reference Wordell, Daratha and Mandal 94 , Reference Collins, Dewar and Schumacher 99 – Reference Dubuy, De Cocker and De Bourdeaudhuij 101 ), who had a low educational level( Reference Yildirim, Singh and te Velde 107 ) or who were living in medically underserved areas( Reference Winett, Roodman and Winett 92 ). Four studies targeted adolescent girls only( Reference Davis, Ventura and Alexander 81 , Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Friend and Flattum 85 , Reference Winett, Roodman and Winett 92 , Reference Collins, Dewar and Schumacher 99 ) and two adolescent boys only( Reference Smith, Morgan and Plotnikoff 100 , Reference Dubuy, De Cocker and De Bourdeaudhuij 101 ). Three studies targeted a mix of normal-weight and overweight adolescents( Reference Jones, Lynch and Kass 38 , Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Friend and Flattum 85 , Reference da Silva Vargas, Sichieri and Sandre-Pereira 103 ), two studies targeted overweight/obese adolescents( Reference Davis, Ventura and Alexander 81 , Reference Pbert, Druker and Gapinski 87 ) and another targeted adolescents at risk for obesity( Reference Smith, Morgan and Plotnikoff 100 ). Finally, three studies targeted specific ethnic minorities in the USA, such as Latina girls( Reference Davis, Ventura and Alexander 81 ), Native Americans( Reference Teufel and Ritenbaugh 89 ) and Inuits( Reference Thiele and Boushey 90 ). It is worth noting that some studies targeted adolescents with multiple sociodemographic characteristics, such as overweight adolescents whose parents had a low SES, which explains why the number of studies in this section exceeds the number of studies included in the review.

Among the twenty-nine studies reporting information on the sex of participants( Reference Jones, Lynch and Kass 38 , Reference Bauhoff 73 – Reference Cradock, McHugh and Mont-Ferguson 79 , Reference Davis, Ventura and Alexander 81 – Reference Lao 83 , Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Friend and Flattum 85 – Reference Teufel and Ritenbaugh 89 , Reference Whittemore, Jeon and Grey 91 , Reference Winett, Roodman and Winett 92 , Reference Wordell, Daratha and Mandal 94 , Reference Lo, Coles and Humbert 96 – Reference Haerens, Deforche and Maes 102 , Reference Wing, Chan and Yu 104 , Reference Singhal, Misra and Shah 105 , Reference Yildirim, Singh and te Velde 107 ), 43·6 % of samples were comprised of adolescent boys. The pooled mean age of the twenty-four studies reporting age was 14·3 years( Reference Jones, Lynch and Kass 38 , Reference Blum, Davee and Beaudoin 74 – Reference Contento, Koch and Lee 77 , Reference Davis, Ventura and Alexander 81 – Reference Lao 83 , Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Friend and Flattum 85 – Reference Teufel and Ritenbaugh 89 , Reference Whittemore, Jeon and Grey 91 , Reference Winett, Roodman and Winett 92 , Reference Lo, Coles and Humbert 96 , Reference Collins, Dewar and Schumacher 99 – Reference Singhal, Misra and Shah 105 , Reference Yildirim, Singh and te Velde 107 ). Finally, twenty-eight studies reported information on the level of education of their participants( Reference Jones, Lynch and Kass 38 , Reference Bauhoff 73 – Reference Cullen, Watson and Zakeri 80 , Reference Greece 82 – Reference Nanney, Maclehose and Kubik 84 , Reference Patel, Bogart and Elliott 86 – Reference Thiele and Boushey 90 , Reference Winett, Roodman and Winett 92 – Reference McGoldrick 98 , Reference Haerens, Deforche and Maes 102 – Reference Singhal, Misra and Shah 105 ). The range of education was from grades 6 to 12. Depending on the country where the study was conducted, this referred to either elementary, middle or high/secondary schools or a mix of these schools.

Behavioural measures of sugar-sweetened beverage consumption

Less than a third (27·8 %) of studies (k 10) used a validated tool to measure SSB consumption( Reference Blum, Davee and Beaudoin 74 , Reference Contento, Koch and Lee 77 , Reference Cullen, Watson and Zakeri 80 – Reference Greece 82 , Reference Pbert, Druker and Gapinski 87 , Reference McGoldrick 98 , Reference Collins, Dewar and Schumacher 99 , Reference Dubuy, De Cocker and De Bourdeaudhuij 101 , Reference Haerens, Deforche and Maes 102 ) and three out of four of the instruments (75·0 %, k 27) were self-administered( Reference Jones, Lynch and Kass 38 , Reference Bauhoff 73 – Reference Bogart, Elliott and Uyeda 75 , Reference Contento, Koch and Lee 77 , Reference Cordeira 78 , Reference Greece 82 – Reference Nanney, Maclehose and Kubik 84 , Reference Patel, Bogart and Elliott 86 , Reference Smith and Holloman 88 , Reference Whittemore, Jeon and Grey 91 – Reference McGoldrick 98 , Reference Smith, Morgan and Plotnikoff 100 – Reference Yildirim, Singh and te Velde 107 ). Among them, two studies used web-based questionnaires, such as a web-based survey( Reference Bae, Kim and Kim 106 ) and a web 24 h recall( Reference McGoldrick 98 ). Three studies did not specify the mode of delivery of their behavioural measure( Reference Cullen, Watson and Zakeri 80 , Reference Teufel and Ritenbaugh 89 , Reference Collins, Dewar and Schumacher 99 ). The most common method for measuring SSB consumption was a survey or questionnaire (50·0 %, k 18)( Reference Jones, Lynch and Kass 38 , Reference Bogart, Elliott and Uyeda 75 , Reference Cordeira 78 , Reference Lao 83 , Reference Nanney, Maclehose and Kubik 84 , Reference Patel, Bogart and Elliott 86 , Reference Smith and Holloman 88 , Reference Whittemore, Jeon and Grey 91 , Reference Woodward-Lopez, Gosliner and Samuels 93 , Reference Nanney, MacLehose and Kubik 95 – Reference Malbon 97 , Reference Smith, Morgan and Plotnikoff 100 , Reference da Silva Vargas, Sichieri and Sandre-Pereira 103 – Reference Yildirim, Singh and te Velde 107 ), followed by 24 h recalls (27·8 %, k 10)( Reference Bauhoff 73 , Reference Casazza 76 , Reference Cradock, McHugh and Mont-Ferguson 79 , Reference Davis, Ventura and Alexander 81 , Reference Nanney, Maclehose and Kubik 84 , Reference Patel, Bogart and Elliott 86 , Reference Smith and Holloman 88 , Reference Teufel and Ritenbaugh 89 , Reference Whittemore, Jeon and Grey 91 , Reference Malbon 97 ), an FFQ (25·0 %, k 9)( Reference Blum, Davee and Beaudoin 74 , Reference Contento, Koch and Lee 77 , Reference Greece 82 , Reference Whittemore, Jeon and Grey 91 , Reference Woodward-Lopez, Gosliner and Samuels 93 , Reference Malbon 97 , Reference McGoldrick 98 , Reference Smith, Morgan and Plotnikoff 100 , Reference Dubuy, De Cocker and De Bourdeaudhuij 101 ) and food records (8·3 %, k 3)( Reference Cullen, Watson and Zakeri 80 , Reference Davis, Ventura and Alexander 81 , Reference Smith and Holloman 88 ). Among the studies that used 24 h recalls, 60·0 % (k 6) chose interviewer-administered( Reference Casazza 76 , Reference Cradock, McHugh and Mont-Ferguson 79 , Reference Davis, Ventura and Alexander 81 , Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Friend and Flattum 85 , Reference Thiele and Boushey 90 ) or telephone-administered( Reference Pbert, Druker and Gapinski 87 ) 24 h recalls for assessing SSB consumption. Four studies (11·1 %) used multiple self-reported tools, such as a 3 d food record and 24 h recalls( Reference Davis, Ventura and Alexander 81 ), a 24 h recall and an FFQ( Reference Winett, Roodman and Winett 92 , Reference McGoldrick 98 ), and a questionnaire and a food record( Reference Smith and Holloman 88 ).

More than 90 % (91·7 %) of studies (k 33) included soft drinks such as soda in their definition of SBB( Reference Jones, Lynch and Kass 38 , Reference Bauhoff 73 – Reference Woodward-Lopez, Gosliner and Samuels 93 , Reference Nanney, MacLehose and Kubik 95 – Reference Collins, Dewar and Schumacher 99 , Reference Dubuy, De Cocker and De Bourdeaudhuij 101 – Reference da Silva Vargas, Sichieri and Sandre-Pereira 103 , Reference Singhal, Misra and Shah 105 – Reference Yildirim, Singh and te Velde 107 ). Among the studies that did not measure soft drinks, one did not specify the type of beverages included in its definition of SSB( Reference Smith, Morgan and Plotnikoff 100 ), another only considered energy drinks( Reference Wing, Chan and Yu 104 ) and one included energy drinks and sweet drinks without specifying if soft drinks were included in the latter category of beverages( Reference Lo, Coles and Humbert 96 ). Seventeen studies (47·2 %) included fruit drinks in their SSB definition( Reference Blum, Davee and Beaudoin 74 , Reference Bogart, Elliott and Uyeda 75 , Reference Contento, Koch and Lee 77 – Reference Cradock, McHugh and Mont-Ferguson 79 , Reference Davis, Ventura and Alexander 81 – Reference Lao 83 , Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Friend and Flattum 85 , Reference Smith and Holloman 88 – Reference Whittemore, Jeon and Grey 91 , Reference Lo, Coles and Humbert 96 – Reference Collins, Dewar and Schumacher 99 ) and twelve studies (33·3 %) sports drinks( Reference Bogart, Elliott and Uyeda 75 , Reference Contento, Koch and Lee 77 , Reference Davis, Ventura and Alexander 81 , Reference Lao 83 – Reference Patel, Bogart and Elliott 86 , Reference Smith and Holloman 88 , Reference Woodward-Lopez, Gosliner and Samuels 93 , Reference Nanney, MacLehose and Kubik 95 , Reference Malbon 97 , Reference McGoldrick 98 ). Nine studies (25·0 %) included either iced tea or sweetened tea and coffee( Reference Blum, Davee and Beaudoin 74 , Reference Contento, Koch and Lee 77 , Reference Davis, Ventura and Alexander 81 , Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Friend and Flattum 85 , Reference Smith and Holloman 88 , Reference Lo, Coles and Humbert 96 – Reference McGoldrick 98 , Reference Yildirim, Singh and te Velde 107 ). Six studies (16·7 %) included energy drinks( Reference Lao 83 , Reference Smith and Holloman 88 , Reference Wordell, Daratha and Mandal 94 , Reference Malbon 97 , Reference Wing, Chan and Yu 104 , Reference Yildirim, Singh and te Velde 107 ) and four studies (11·1 %) included other types of SSB such as cordial concentrates( Reference Collins, Dewar and Schumacher 99 ), drink mixes( Reference Contento, Koch and Lee 77 ), slush( Reference Malbon 97 ) and lemonade( Reference Yildirim, Singh and te Velde 107 ). Finally, three studies (8·3 %) had a general ‘sweet drinks’ category( Reference Cullen, Watson and Zakeri 80 , Reference Pbert, Druker and Gapinski 87 , Reference Wordell, Daratha and Mandal 94 ).

Nine studies (25·0 %) only measured the impact of their intervention on soft drinks consumption( Reference Jones, Lynch and Kass 38 , Reference Bauhoff 73 , Reference Casazza 76 , Reference Winett, Roodman and Winett 92 , Reference Dubuy, De Cocker and De Bourdeaudhuij 101 – Reference da Silva Vargas, Sichieri and Sandre-Pereira 103 , Reference Wing, Chan and Yu 104 , Reference Bae, Kim and Kim 106 ). Slightly more than a third (36·1 %) of studies included two types of SSB (k 13), generally soft drinks and fruit drinks( Reference Cordeira 78 – Reference Cullen, Watson and Zakeri 80 , Reference Greece 82 , Reference Nanney, Maclehose and Kubik 84 , Reference Patel, Bogart and Elliott 86 , Reference Pbert, Druker and Gapinski 87 , Reference Teufel and Ritenbaugh 89 – Reference Whittemore, Jeon and Grey 91 , Reference Woodward-Lopez, Gosliner and Samuels 93 – Reference Nanney, MacLehose and Kubik 95 ). Three studies (8·3 %) included three types of SSB( Reference Blum, Davee and Beaudoin 74 , Reference Bogart, Elliott and Uyeda 75 , Reference Collins, Dewar and Schumacher 99 ) and six studies (16·7 %) reported information on four categories of SSB( Reference Davis, Ventura and Alexander 81 , Reference Lao 83 , Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Friend and Flattum 85 , Reference Lo, Coles and Humbert 96 , Reference McGoldrick 98 , Reference Yildirim, Singh and te Velde 107 ). Finally, three studies (8·3 %) included five types of SSB( Reference Contento, Koch and Lee 77 , Reference Smith and Holloman 88 , Reference Malbon 97 ) and among them, only one study( Reference Smith and Holloman 88 ) included all of our five categories of SSB, namely soft drinks, fruit drinks, sports drinks, energy drinks and sweetened tea or coffee (iced or hot)( 70 ).

Study designs and quality of studies

Thirteen interventions (36·1 %) were RCT or cluster RCT( Reference Casazza 76 , Reference Contento, Koch and Lee 77 , Reference Davis, Ventura and Alexander 81 , Reference Lao 83 , Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Friend and Flattum 85 , Reference Pbert, Druker and Gapinski 87 , Reference Whittemore, Jeon and Grey 91 , Reference Collins, Dewar and Schumacher 99 , Reference Smith, Morgan and Plotnikoff 100 , Reference Haerens, Deforche and Maes 102 , Reference Wing, Chan and Yu 104 , Reference Singhal, Misra and Shah 105 , Reference Yildirim, Singh and te Velde 107 ). A third of studies (33·3 %, k 12) adopted a one-group pre–post study design, mainly those aimed at evaluating the impact of nutrition policies in schools (i.e. SSB consumption pre- and post-policy)( Reference Jones, Lynch and Kass 38 , Reference Bauhoff 73 , Reference Cordeira 78 , Reference Cullen, Watson and Zakeri 80 , Reference Nanney, Maclehose and Kubik 84 , Reference Smith and Holloman 88 , Reference Teufel and Ritenbaugh 89 , Reference Woodward-Lopez, Gosliner and Samuels 93 , Reference Nanney, MacLehose and Kubik 95 , Reference Malbon 97 , Reference McGoldrick 98 , Reference Bae, Kim and Kim 106 ). Eleven interventions (30·6 %) used quasi-experimental designs( Reference Blum, Davee and Beaudoin 74 , Reference Bogart, Elliott and Uyeda 75 , Reference Cradock, McHugh and Mont-Ferguson 79 , Reference Greece 82 , Reference Patel, Bogart and Elliott 86 , Reference Thiele and Boushey 90 , Reference Winett, Roodman and Winett 92 , Reference Wordell, Daratha and Mandal 94 , Reference Lo, Coles and Humbert 96 , Reference Dubuy, De Cocker and De Bourdeaudhuij 101 , Reference da Silva Vargas, Sichieri and Sandre-Pereira 103 ).

Over 60 % (61·1 %) of studies (k 22) received a weak global rating for their quality according to the EPHPP tool( Reference Jones, Lynch and Kass 38 , Reference Blum, Davee and Beaudoin 74 – Reference Casazza 76 , Reference Cordeira 78 , Reference Lao 83 , Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Friend and Flattum 85 , Reference Patel, Bogart and Elliott 86 , Reference Smith and Holloman 88 – Reference Wordell, Daratha and Mandal 94 , Reference Lo, Coles and Humbert 96 , Reference Malbon 97 , Reference Smith, Morgan and Plotnikoff 100 , Reference Dubuy, De Cocker and De Bourdeaudhuij 101 , Reference da Silva Vargas, Sichieri and Sandre-Pereira 103 , Reference Wing, Chan and Yu 104 , Reference Yildirim, Singh and te Velde 107 ). Over 80 % (81·8 %) of quasi-experimental studies (k 9) received a weak global rating( Reference Blum, Davee and Beaudoin 74 , Reference Bogart, Elliott and Uyeda 75 , Reference Patel, Bogart and Elliott 86 , Reference Thiele and Boushey 90 , Reference Winett, Roodman and Winett 92 , Reference Wordell, Daratha and Mandal 94 , Reference Lo, Coles and Humbert 96 , Reference Dubuy, De Cocker and De Bourdeaudhuij 101 , Reference da Silva Vargas, Sichieri and Sandre-Pereira 103 ), followed by one-group pre–post studies (50·0 %, k 6)( Reference Jones, Lynch and Kass 38 , Reference Cordeira 78 , Reference Smith and Holloman 88 , Reference Teufel and Ritenbaugh 89 , Reference Woodward-Lopez, Gosliner and Samuels 93 , Reference Malbon 97 ) and RCT (53·8 %, k 7)( Reference Casazza 76 , Reference Lao 83 , Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Friend and Flattum 85 , Reference Whittemore, Jeon and Grey 91 , Reference Smith, Morgan and Plotnikoff 100 , Reference Wing, Chan and Yu 104 , Reference Yildirim, Singh and te Velde 107 ). The three most frequent reasons for a weak global rating were: (i) presence of a selection bias; (ii) no blinding; and (iii) the data collection tool was not valid or reliable. A third (33·3 %) of studies (k 12) received a global rating of moderate quality( Reference Bauhoff 73 , Reference Contento, Koch and Lee 77 , Reference Cradock, McHugh and Mont-Ferguson 79 , Reference Davis, Ventura and Alexander 81 , Reference Greece 82 , Reference Nanney, Maclehose and Kubik 84 , Reference Pbert, Druker and Gapinski 87 , Reference Nanney, MacLehose and Kubik 95 , Reference McGoldrick 98 , Reference Collins, Dewar and Schumacher 99 , Reference Singhal, Misra and Shah 105 , Reference Bae, Kim and Kim 106 ). Close to 40 % (38·5 %) of RCT (k 5) received a global moderate rating( Reference Contento, Koch and Lee 77 , Reference Davis, Ventura and Alexander 81 , Reference Pbert, Druker and Gapinski 87 , Reference Collins, Dewar and Schumacher 99 , Reference Singhal, Misra and Shah 105 ), followed by one-group pre–post studies (33·3 %, k 4)( Reference Bauhoff 73 , Reference Nanney, Maclehose and Kubik 84 , Reference McGoldrick 98 , Reference Bae, Kim and Kim 106 ) and quasi-experimental studies (18·2 %, k 2)( Reference Cradock, McHugh and Mont-Ferguson 79 , Reference Greece 82 ). Finally, only two studies received a strong global rating according to the EPHPP tool. One was a one-group pre–post study that evaluated the impact of a school nutrition policy on SBB consumption using validated food records( Reference Cullen, Watson and Zakeri 80 ). The other was an RCT on healthy eating and physical activity which used a validated self-administered FFQ to assess SSB consumption( Reference Haerens, Deforche and Maes 102 ).

Results of interventions

Over 70 % (72·2 %, k 26) of all interventions, regardless of whether they targeted individuals, their environment or both, were effective in decreasing SSB consumption( Reference Jones, Lynch and Kass 38 , Reference Bauhoff 73 – Reference Contento, Koch and Lee 77 , Reference Cradock, McHugh and Mont-Ferguson 79 – Reference Greece 82 , Reference Nanney, Maclehose and Kubik 84 , Reference Smith and Holloman 88 – Reference Woodward-Lopez, Gosliner and Samuels 93 , Reference Nanney, MacLehose and Kubik 95 , Reference Lo, Coles and Humbert 96 , Reference McGoldrick 98 – Reference Smith, Morgan and Plotnikoff 100 , Reference Wing, Chan and Yu 104 – Reference Yildirim, Singh and te Velde 107 ). Their efficacy, however, varied according to the type of intervention (see Table 2). The ten legislative/environmental studies had the highest success rate, with nine studies (90·0 %) reporting a significant reduction in SSB consumption( Reference Bauhoff 73 , Reference Blum, Davee and Beaudoin 74 , Reference Cradock, McHugh and Mont-Ferguson 79 , Reference Cullen, Watson and Zakeri 80 , Reference Greece 82 , Reference Nanney, Maclehose and Kubik 84 , Reference Woodward-Lopez, Gosliner and Samuels 93 , Reference Nanney, MacLehose and Kubik 95 , Reference McGoldrick 98 ) and only one study with no significant reduction in SSB consumption following changes in the school food environment( Reference Wordell, Daratha and Mandal 94 ). The twenty educational/behavioural interventions and the six interventions that were both educational/behavioural and legislative/environmental were almost equally effective in reducing SSB consumption, with success rates of 65·0 % (k 13)( Reference Jones, Lynch and Kass 38 , Reference Casazza 76 , Reference Contento, Koch and Lee 77 , Reference Davis, Ventura and Alexander 81 , Reference Smith and Holloman 88 , Reference Thiele and Boushey 90 – Reference Winett, Roodman and Winett 92 , Reference Lo, Coles and Humbert 96 , Reference Collins, Dewar and Schumacher 99 , Reference Smith, Morgan and Plotnikoff 100 , Reference Wing, Chan and Yu 104 , Reference Singhal, Misra and Shah 105 ) and 66·7 % (k 4)( Reference Bogart, Elliott and Uyeda 75 , Reference Teufel and Ritenbaugh 89 , Reference Bae, Kim and Kim 106 , Reference Yildirim, Singh and te Velde 107 ), respectively. It is noteworthy that one legislative/environmental study( Reference McGoldrick 98 ) and one educational/behavioural intervention( Reference Jones, Lynch and Kass 38 ) reported significant increases in SSB consumption post-intervention.

Theory used in designing interventions

Among the twenty-six interventions that had an educational/behavioural component, over 60 % (61·5 %, k 16) of studies were based on behavioural theories( Reference Bogart, Elliott and Uyeda 75 – Reference Cordeira 78 , Reference Lao 83 , Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Friend and Flattum 85 , Reference Pbert, Druker and Gapinski 87 , Reference Whittemore, Jeon and Grey 91 , Reference Winett, Roodman and Winett 92 , Reference Lo, Coles and Humbert 96 , Reference Malbon 97 , Reference Collins, Dewar and Schumacher 99 – Reference Haerens, Deforche and Maes 102 , Reference Yildirim, Singh and te Velde 107 ). The theory most frequently used to design this type of intervention was the SCT( Reference Bandura 46 ) and its predecessor the SLT( Reference Bandura 47 ) (k 10)( Reference Bogart, Elliott and Uyeda 75 – Reference Cordeira 78 , Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Friend and Flattum 85 , Reference Patel, Bogart and Elliott 86 , Reference Whittemore, Jeon and Grey 91 , Reference Winett, Roodman and Winett 92 , Reference Collins, Dewar and Schumacher 99 , Reference Smith, Morgan and Plotnikoff 100 ), followed by the TPB( Reference Ajzen 48 ) (k 4)( Reference Bogart, Elliott and Uyeda 75 , Reference Casazza 76 , Reference Haerens, Deforche and Maes 102 , Reference Yildirim, Singh and te Velde 107 ), the TTM( Reference Prochaska and DiClemente 49 ) (k 4)( Reference Casazza 76 , Reference Lao 83 , Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Friend and Flattum 85 , Reference Haerens, Deforche and Maes 102 ) and the SDT( Reference Ryan and Deci 50 ) (k 3)( Reference Contento, Koch and Lee 77 , Reference Malbon 97 , Reference Smith, Morgan and Plotnikoff 100 ). It is worth noting that all of them are psychosocial theories (i.e. theories originating from social psychology) related to human motivation/intention. Other theories were mentioned by only one study. More than half (56·3 %, k 9) of theory-based interventions were effective in reducing SSB consumption( Reference Bogart, Elliott and Uyeda 75 – Reference Contento, Koch and Lee 77 , Reference Whittemore, Jeon and Grey 91 , Reference Winett, Roodman and Winett 92 , Reference Lo, Coles and Humbert 96 , Reference Collins, Dewar and Schumacher 99 , Reference Smith, Morgan and Plotnikoff 100 , Reference Yildirim, Singh and te Velde 107 ).

Behaviour change techniques used in interventions

As previously mentioned, the majority of interventions targeted the reduction of SSB consumption as part of a general objective to promote healthy eating and physical activity or healthy eating alone. Consequently, the majority of the behaviour change techniques were directed towards promoting the larger behaviours (healthy eating and/or physical activity). Nevertheless, an effort was made to code only the behaviour change techniques related to SSB consumption and not those related to healthy eating (e.g. fruit and vegetable consumption) and/or physical activity when possible. When this was not possible, only the behaviour change techniques related to healthy eating and not those related to physical activity were coded. However, in some studies, the curriculum of the intervention that specifically targeted SSB and/or healthy eating was not stated.

The behaviour change techniques that were the most frequently used in interventions were providing information about the health consequences of performing the behaviour (72·2 %, k 26)( Reference Jones, Lynch and Kass 38 , Reference Bogart, Elliott and Uyeda 75 – Reference Cordeira 78 , Reference Greece 82 , Reference Lao 83 , Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Friend and Flattum 85 – Reference Winett, Roodman and Winett 92 , Reference Lo, Coles and Humbert 96 , Reference Malbon 97 , Reference Collins, Dewar and Schumacher 99 – Reference Yildirim, Singh and te Velde 107 ), followed by restructuring the physical environment (47·2 %, k 17)( Reference Bauhoff 73 – Reference Bogart, Elliott and Uyeda 75 , Reference Cradock, McHugh and Mont-Ferguson 79 , Reference Cullen, Watson and Zakeri 80 , Reference Greece 82 , Reference Nanney, Maclehose and Kubik 84 , Reference Patel, Bogart and Elliott 86 , Reference Teufel and Ritenbaugh 89 , Reference Woodward-Lopez, Gosliner and Samuels 93 – Reference Nanney, MacLehose and Kubik 95 , Reference McGoldrick 98 , Reference Haerens, Deforche and Maes 102 , Reference Singhal, Misra and Shah 105 – Reference Yildirim, Singh and te Velde 107 ), behavioural goal setting (36·1 %, k 13)( Reference Jones, Lynch and Kass 38 , Reference Casazza 76 – Reference Cordeira 78 , Reference Davis, Ventura and Alexander 81 , Reference Lao 83 , Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Friend and Flattum 85 , Reference Pbert, Druker and Gapinski 87 , Reference Whittemore, Jeon and Grey 91 , Reference Winett, Roodman and Winett 92 , Reference Malbon 97 , Reference Smith, Morgan and Plotnikoff 100 , Reference Yildirim, Singh and te Velde 107 ), self-monitoring of behaviour (33·3 %, k 12)( Reference Jones, Lynch and Kass 38 , Reference Casazza 76 , Reference Contento, Koch and Lee 77 , Reference Davis, Ventura and Alexander 81 , Reference Pbert, Druker and Gapinski 87 , Reference Whittemore, Jeon and Grey 91 , Reference Winett, Roodman and Winett 92 , Reference Malbon 97 , Reference Collins, Dewar and Schumacher 99 , Reference Smith, Morgan and Plotnikoff 100 , Reference Wing, Chan and Yu 104 , Reference Yildirim, Singh and te Velde 107 ), threat to health (30·6 %, k 11)( Reference Jones, Lynch and Kass 38 , Reference Casazza 76 – Reference Cordeira 78 , Reference Lao 83 , Reference Teufel and Ritenbaugh 89 , Reference Teufel and Ritenbaugh 89 , Reference Smith, Morgan and Plotnikoff 100 , Reference da Silva Vargas, Sichieri and Sandre-Pereira 103 – Reference Singhal, Misra and Shah 105 ) and providing general social support (30·6 %, k 11)( Reference Jones, Lynch and Kass 38 , Reference Casazza 76 , Reference Cordeira 78 , Reference Lao 83 , Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Friend and Flattum 85 , Reference Teufel and Ritenbaugh 89 , Reference Whittemore, Jeon and Grey 91 , Reference Collins, Dewar and Schumacher 99 , Reference Smith, Morgan and Plotnikoff 100 , Reference Haerens, Deforche and Maes 102 , Reference Yildirim, Singh and te Velde 107 ). The other behaviour change techniques were mentioned in ten or fewer different studies. The majority of legislative/environmental studies used only one behaviour change technique (i.e. restructuring the physical environment) while the majority of interventions with an educational/behavioural component used multiple behaviour change techniques. Restructuring the physical environment was a frequently used behaviour change technique given that all legislative/environmental studies aimed at evaluating the impact of school nutrition policies implied some changes in the school environment, such as banning SBB or replacing SSB by healthier alternatives (e.g. water, milk, 100 % pure fruit juices). The majority of educational/behavioural interventions explained to adolescents the negative health consequences of consuming SSB and they also sometimes included a component about threat to health when they further explained how chronic diseases related to SSB consumption, such as obesity and type 2 diabetes, can be detrimental to health. Behavioural goal setting (e.g. setting an objective to decrease one’s own SSB consumption by one serving per day by next week), self-monitoring of behaviour (e.g. recording one’s own daily consumption of SSB) and providing general social support were other behaviour change techniques commonly part of interventions with an educational/behavioural component. Parents (72·7 %, k 8)( Reference Jones, Lynch and Kass 38 , Reference Casazza 76 , Reference Cordeira 78 , Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Friend and Flattum 85 , Reference Teufel and Ritenbaugh 89 , Reference Collins, Dewar and Schumacher 99 , Reference Smith, Morgan and Plotnikoff 100 , Reference Haerens, Deforche and Maes 102 ) and/or friends (45·5 %, k 5)( Reference Casazza 76 , Reference Cordeira 78 , Reference Lao 83 , Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Friend and Flattum 85 , Reference Yildirim, Singh and te Velde 107 ) were enlisted for social support and one study did not report from which specific persons social support was sought( Reference Whittemore, Jeon and Grey 91 ). In some studies, parents received written material (newsletters, text messages, emails, postcards)( Reference Jones, Lynch and Kass 38 , Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Friend and Flattum 85 , Reference Collins, Dewar and Schumacher 99 , Reference Smith, Morgan and Plotnikoff 100 , Reference Haerens, Deforche and Maes 102 ) and/or were invited to school meetings( Reference Teufel and Ritenbaugh 89 , Reference Haerens, Deforche and Maes 102 ) to encourage them to support their adolescent to change his/her behaviour.

Finally, only four studies (11·1 %) used a control group which received some kind of intervention (i.e. active control group)( Reference Davis, Ventura and Alexander 81 , Reference Pbert, Druker and Gapinski 87 , Reference Whittemore, Jeon and Grey 91 , Reference Lo, Coles and Humbert 96 ). Among those studies, two had only one or two behaviour change techniques differentiating the experimental and the control group( Reference Whittemore, Jeon and Grey 91 , Reference Lo, Coles and Humbert 96 ) while the other two studies had six behaviour change techniques differentiating both groups( Reference Davis, Ventura and Alexander 81 , Reference Pbert, Druker and Gapinski 87 ). Unfortunately, it was not possible to identify the most effective behaviour change technique given that studies with an educational/behavioural component often used a combination of different behaviour change techniques in their experimental group.

Discussion

The results of the present systematic review indicate that the majority of school-based interventions are effective at reducing SSB consumption among adolescents, although the overall rating of the interventions was frequently weak. This suggests that the school setting might represent a promising place to easily reach adolescents, regardless of their age, SES, cultural background and ethnicity( Reference Flynn, McNeil and Maloff 32 , Reference Bandura 37 , Reference Jones, Lynch and Kass 38 ). For example, in the present systematic review, a few studies targeted adolescents whose parents had a low SES( Reference Contento, Koch and Lee 77 , Reference Greece 82 , Reference Lao 83 , Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Friend and Flattum 85 , Reference Patel, Bogart and Elliott 86 , Reference Smith and Holloman 88 , Reference Woodward-Lopez, Gosliner and Samuels 93 , Reference Wordell, Daratha and Mandal 94 , Reference Collins, Dewar and Schumacher 99 – Reference Dubuy, De Cocker and De Bourdeaudhuij 101 ) or specific ethnic minorities in the USA( Reference Davis, Ventura and Alexander 81 , Reference Teufel and Ritenbaugh 89 , Reference Thiele and Boushey 90 ). Given that parents’ lower SES can be associated with SSB consumption among young children( Reference Mazarello Paes, Hesketh and O’Malley 108 ), schools – especially those in low-income neighbourhoods – could be a good place to reach adolescents at high risk for SSB consumption.

According to the present findings, legislative/environmental interventions were the most effective while educational/behavioural interventions and those targeting both individuals and their environment were less, but both equally effective, at decreasing SSB consumption among adolescents. Overall, this suggests that governmental efforts to reduce availability and/or eliminate SSB in schools should be pursued. However, governmental nutrition policies can also have unintended consequences. For example, one study conducted in Canada reported that while frequency of SSB consumption decreased following a ban on SSB in schools, the volume of SBB (in millilitres) consumed increased( Reference McGoldrick 98 ). In other words, adolescents might report consuming SSB less frequently simply because they drink larger quantities each time they consume SSB. This could reflect a trend of the industry to continuously increase the size of the SBB it sells over the years( Reference Nielsen and Popkin 109 ). Another study in the USA observed that while the overall mean servings of SSB in school decreased following the implementation of a school nutrition policy, three times more adolescents mentioned bringing SBB from home post-policy( Reference Cullen, Watson and Zakeri 80 ). Similarly, the results of another study not included in the present review (the outcome was SSB sales) suggested that when there is a ban on SSB in schools, some adolescents instead buy SSB in stores located on their school commute( Reference Grummon, Oliva and Hampton 110 ). One way of possibly avoiding these unintended consequences could be to provide educational/behavioural activities among adolescents and their parents about the negative consequences associated with consuming SSB as well as tips to promote drinking heathier alternatives and to overcome the barriers that could be encountered. This could help adolescents make healthy choices when they are outside school and parents could also support them by providing non-SSB at home, such as water and milk. In fact, substituting SBB with water and milk can have a positive effect on body fatness of adolescents( Reference Zheng, Rangan and Olsen 111 ). Yet, in the present review, only six interventions targeted both individuals and their environment as recommended by ecological models often used to design public health interventions( Reference Sallis, Owen and Fisher 39 ) and by research specifically targeting obesity prevention and healthy eating among children and adolescents( Reference Sharma 69 , Reference Veugelers and Fitzgerald 112 , Reference Flodmark, Marcus and Britton 113 ).

Among studies including an educational/behavioural component, more than half were based on a psychosocial theory, such as the SCT/SLT, TPB, TTM and SDT, which are some of the most commonly used theories for developing public health interventions( Reference Glanz and Bishop 114 ). This is an interesting finding as over the years, a number of authors have advocated for the use of theory in designing public health interventions( Reference Baranowski, Lin and Wetter 40 – Reference Michie and Abraham 44 , Reference Glanz and Bishop 114 , Reference Bartholomew and Mullen 115 ). In fact, among the theory-based interventions included in the present review, more than half of them were effective in reducing SSB consumption among adolescents. While at first sight this might seem like a rather low success rate, current evidence regarding the efficacy of theory-based interventions is conflicting, with some studies reporting that theory-based interventions are more effective than those not theory-based( Reference Glanz and Bishop 114 , Reference Webb, Joseph and Yardley 116 ) while others report that both theory-based and non-theory-based interventions are equally effective in changing health behaviour( Reference Prestwich, Sniehotta and Whittington 117 ). Nevertheless, one advantage of using a theory is the potential to guide the choice of behaviour change techniques to use in interventions( Reference Michie, Johnston and Francis 51 , Reference Abraham and Michie 52 ).

It is interesting to note that while a majority of interventions report being based on the SCT/SLT, TPB, TTM and SDT, none of the most popular behaviour change techniques previously discussed – except providing information about health consequences, which is part of the SCT/SLT and the TPB – are recommended by any of these psychosocial theories( Reference Abraham and Michie 52 ). Unfortunately, it is rather common that behaviour change techniques used in interventions are not necessarily related to the theory that interventions are supposed to be based on( Reference Prestwich, Sniehotta and Whittington 117 ), which is why some authors came up with the expression ‘theory-inspired’ instead of ‘theory-based’ to describe certain interventions( Reference Michie, Carey and Johnston 54 ). This could also explain the somewhat low success rate of theory-based interventions because using behaviour change techniques linked to the chosen theory should be more effective at changing behaviour than using theory-irrelevant behaviour change techniques( Reference Prestwich, Sniehotta and Whittington 117 ).

Finally, in the present review, providing information on the health consequences related to SSB consumption was the most frequently used behaviour change technique. While knowledge of the health benefits and risks of a particular behaviour is a requirement and one of the first steps for behaviour change, it is usually deemed not sufficient to engender behaviour change according to the author of the SCT/SLT( Reference Bandura 118 ). Other behaviour change techniques need to be used in conjunction with this strategy. Self-monitoring of behaviour was another behaviour change technique often used in interventions aimed at decreasing SSB consumption among adolescents. In fact, according to previous reviews, self-monitoring is one of the most commonly used techniques to promote physical activity among overweight/obese adults( Reference Bélanger-Gravel, Godin and Vézina-Im 119 ) and it is also consistently associated with behaviour change( Reference Harkin, Webb and Chang 120 , Reference Michie, Abraham and Whittington 121 ) and with weight loss( Reference Burke, Wang and Sevick 122 ), which might explain its popularity. Behavioural goal setting was also a prevalent behaviour change technique to encourage adolescents to reduce their SSB consumption. Previous reviews found that goal setting is an effective strategy to promote health behaviour changes among overweight/obese adults( Reference Pearson 123 ) and people with type 2 diabetes( Reference Miller and Bauman 124 ). Providing general social support was another frequent component of interventions whose objective was to lower SSB consumption among adolescents. As previously mentioned, parents play an important role in encouraging their adolescents to develop healthy habits outside school. In the articles included in the present systematic review, they were the persons most frequently solicited for social support and some studies even targeted them in their interventions by sending them written material and/or inviting them to school meetings. In fact, according to ecological models used in public health( Reference Sallis, Owen and Fisher 39 ) and supported by empirical work aimed at improving nutrition and preventing obesity among youth( Reference Flynn, McNeil and Maloff 32 , Reference Sharma 69 , Reference Waters, de Silva-Sanigorski and Hall 125 ), interventions that target different levels of social influences, such as adolescents, their parents and the school environment, should be more effective at changing health behaviours than those simply aimed at individuals.

Recommendations for future studies

More studies targeting individuals and their environment, as recommended by ecological models used in public health( Reference Sallis, Owen and Fisher 39 ), are needed to avoid unintended consequences associated with interventions only aimed at changing the school food environment. Ideally, theory-based interventions should choose behaviour change techniques relevant to their choice of theory. Authors whose interventions are aimed at multiple health behaviours, such as healthy eating (including SSB consumption) and physical activity, should clearly report which behaviour change techniques were used for each behaviour. This information would help distinguish which behaviour change techniques are the most effective for improving each specific behaviour. To facilitate replication, authors are encouraged to briefly explain how each behaviour change technique was used. In many of the included studies, authors simply reported using goal setting and self-monitoring without specifying how this was applied. This information is important given that there is evidence that increasing the level of specificity of certain behaviour change techniques increases the chances of successfully changing behaviour. For example, action planning is a behaviour change technique similar to goal setting, but that requires more detailed planning, such as specifying at least one of the following components: the context, frequency, intensity and duration of the behaviour( Reference Cane, Richardson and Johnston 53 ). Recent studies found that adults who made more specific action plans had greater odds of attaining their goal concerning fruit or vegetable intake or physical activity( Reference Plaete, De Bourdeaudhuij and Verloigne 126 ) and experienced greater weight loss when they had high weight-loss goals( Reference Dombrowski, Endevelt and Steinberg 127 ). To improve the quality of their study and also facilitate comparison across studies, authors are also advised to use a valid and reliable measure of SSB consumption to obtain precise information on both frequency (e.g. times per day or per week) and quantity (e.g. in millilitres or fluid ounces) of SBB consumed. Finally, authors are encouraged to not just include soft drinks in their definition of SSB given that other types of SSB such as sports drinks and energy drinks are increasingly more popular among adolescents( Reference Harris and Munsell 128 ) and are equally detrimental to health( Reference Ali, Rehman and Babayan 55 , Reference Richards and Smith 129 – 131 ). There is also evidence that when only sodas are banned in schools, adolescents replace them by other SBB, such as sports drinks, energy drinks and sweetened coffee and tea( Reference Taber, Chriqui and Vuillaume 132 ). However, when including different types of SSB, authors are advised to report on types of SSB separately in case their intervention has a different effect on each drink included in their definition.

Limitations of the systematic review

Unfortunately, it was not possible to conduct a meta-analysis on the efficacy of interventions given the important heterogeneity observed between studies. Part of this heterogeneity could result from the inclusion of different individual measures of SSB consumption (e.g. millilitres or number of glasses per day or per week, percentage of individuals who reported consuming a given quantity of SSB, etc.) and also different measures of this outcome (e.g. different types of SSB reported separately or collectively) in the present systematic review. This decision was made since there was no consensus on how to measure individual SSB consumption. In fact, a recent review of methods to assess intake of SSB among adults, adolescents and children concluded that there is a need for an agreed definition of SSB among instruments measuring this behaviour( Reference Riordan, Ryan and Perry 62 ). At the same time, a strength of the present review was the inclusion of different types of intervention, such as educational/behavioural and legislative/environmental interventions, as both can inform the development of school-based interventions and are relevant for public health. The inclusion of different study designs was another strength( Reference Valentine and Thompson 133 ), since including only RCT would have excluded studies reporting the efficacy of school nutrition policies. It was also not possible to verify the presence of a publication bias, which could explain why the majority of the studies reported a significant reduction of SSB consumption after their intervention. To lower the risk of encountering this bias, grey literature (i.e. unpublished trials) was included in the present review.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, the present study is the first to systematically review school-based interventions aimed at reducing SSB consumption among adolescents. It also applied the taxonomy of Cane et al.( Reference Cane, Richardson and Johnston 53 ) to classify the behaviour change techniques used in interventions. Another novel aspect of the current review is the assessment of the quality of each study using the EPHPP tool( Reference Armijo-Olivo, Stiles and Hagen 71 ). As such, the present review contributes to identify gaps in knowledge and suggest new directions for people wishing to develop school-based interventions to effectively reduce SSB consumption among adolescents.

School-based interventions show promising results to reduce SSB consumption among adolescents and governmental efforts to reduce availability and/or eliminate SSB in schools should be pursued. More studies targeting individuals and their environment, as recommended by ecological models used in public health( Reference Sallis, Owen and Fisher 39 ), are needed to avoid unintended consequences associated with interventions aimed only at changing the school food environment. Finally, it is hoped that these findings and the growing rates of obesity among adolescents will encourage public health authorities and researchers to pursue their efforts to encourage adolescents to adopt healthy drinking habits, such as replacing SSB by water or milk( Reference Zheng, Rangan and Olsen 111 ), which could be maintained throughout life.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of Marie-Ève Émond-Beaulieu who helped with the search strategy. Financial support: This work was supported by a grant from Université du Québec à Rimouski (UQAR) (grant number TRF C3-751325). UQAR had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: L.-A.V.-I. conducted the search strategy and its update in each database, selected studies for their inclusion in the systematic review, extracted and analysed the data, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript with Do.B. Do.B. designed the review with L.-A.V.-I., registered the protocol in PROSPERO, confirmed the study selection, did the second data extraction for a selection of articles and critically revised the manuscript. A.B.-G., D.a.B. and M.D. did the second data extraction for a selection of articles and critically revised the paper. C.S. and V.P. critically revised the manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: Not applicable.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980017000076