What are these US research organizations and foundations: the George Soros Foundation, the Ford Foundation, and others that have opened up shop in Russia? Why are they here?

—Report by the Russian Federal Counterintelligence Service, January 1995Footnote 1The dissolution of the Soviet Union and the third wave of democratization in the early 1990s gave a massive boost to the proliferation of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in Central and Eastern Europe. These NGOs sought to tackle a range of issues: institutional development, establishing and supporting electoral processes, and working to reduce ethnic conflict, to name a few.Footnote 2 As such, NGOs began to be seen in the West as a precondition for democratic transition and consolidation, protecting against authoritarian overreach and holding governments accountable.Footnote 3

However, while Western states were enthusiastic about NGOs because NGOs espoused the same liberal values these states ostensibly promoted, many host countries began viewing them with skepticism. In Russia, for example, Putin believed the West had orchestrated the color revolutions in Georgia, Ukraine, and Kyrgyzstan—which led to widespread protests and regime change—through their support of local NGOs and activists.Footnote 4 Following years of increasingly vocal suspicion, in 2006 Russian authorities passed a law restricting NGO activity.Footnote 5 This was followed in 2012 by the infamous “foreign agent” law, which forced organizations receiving foreign funding and engaging in political activities to register as foreign agents, a term intended to stigmatize NGOs.Footnote 6 Moscow argued that this crackdown was prompted by the excessively political role of US and Western European aid to NGOs.Footnote 7

Under the Bush administration's Freedom Agenda, the spread of democratic ideals worldwide became even more clearly linked with US national security objectives.Footnote 8 US Secretary of State Colin Powell commented in 2001, “American NGOs are out there serving and sacrificing on the frontlines of freedom. NGOs are such a force multiplier for us, such an important part of our combat team.”Footnote 9 Such statements did little to allay the concerns of foreign leaders.

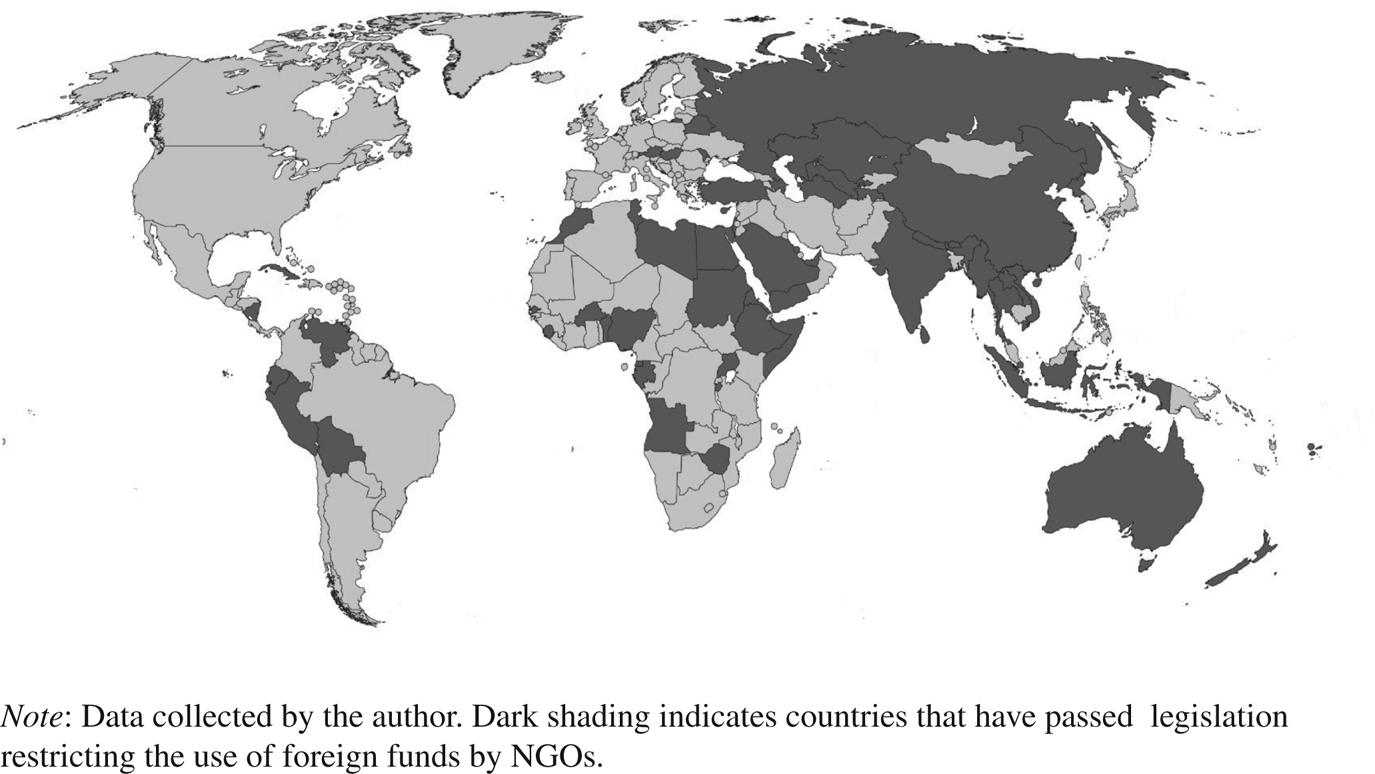

Research has shown that NGOs can wield real influence in ways that can be threatening to states. These organizations can influence electoral politics,Footnote 10 aid mobilization,Footnote 11 and threaten a state's economic interests.Footnote 12 In response, states have increasingly chosen to repress NGOs they perceive as threatening. In this article, I argue that when states decide to repress NGOs, they have two main strategies at their disposal: violent or administrative. Administrative crackdown is a nonviolent strategy which entails enacting legal restrictions to create barriers to entry, funding, and advocacy by NGOs.Footnote 13 Hampering foreign funding is the most insidious of these tactics because without adequate funds NGOs cannot continue their operations in target countries. Both democracies and autocracies have used this tactic to repress NGOs (Figure 1). More broadly, since the end of the Cold War, more than 130 countries have engaged in NGO repression. When they choose to repress NGOs, under what conditions do states use violent strategies versus administrative means?

Figure 1. Barriers to foreign funding for NGOs, 2017

I argue that, once states decide to repress NGOs, the choice of strategy (violent or administrative) depends on two factors: the nature of the threat posed by these groups, and the international consequences of cracking down on them. Violent crackdowns address a state's short-term strategic goals. When states are dealing with immediate threats, such as ongoing protests, they are more likely to violently repress NGOs they see as aiding these activities. However, violence has consequences: it can increase the state's criminal liability, reduce its legitimacy domestically and internationally, violate human rights treaties, and intensify mobilization against the regime. State agents may even refuse to implement violent orders. To avoid these consequences, states often look for strategies to prevent various forms of collective action from coalescing in the first place.

I argue that states are more likely to undertake administrative crackdown as a long-term strategy, especially in dealing with threats preventively. This is the case particularly when NGOs have the potential to influence electoral participation or challenge key economic interests of the state. Administrative crackdown has smaller domestic consequences than violence. Citizens are likely to see administrative crackdown as a form of regulation rather than repression, making a backlash less likely. The international consequences are also fewer, since administrative actions are less likely than violence to invite condemnation, shaming, or threats of aid withdrawal.

Using panel data on all countries from 1990 to 2013 and an original data set on state repression of NGOs using administrative crackdown, I demonstrate that as elections become increasingly competitive, states are, on average, more likely to repress NGOs via administrative means. However, administrative crackdown is not the state's main choice of strategy when NGOs pose immediate threats. Instead, a higher number of protests is positively and significantly associated with the use of violence against NGOs and activists. I provide qualitative evidence for the proposed mechanisms through a case from India. Through interviews with state elites and NGOs, this case sheds light on how states choose between different crackdown strategies. The case study also explores how states perceive varying levels of threats from domestic and international NGOs, even when they work on similar issues.

This article makes two main contributions. First, it develops a new theory of the conditions under which states, when they decide to repress NGOs, choose violent or administrative means. Although violent responses to dissent have been studied extensively,Footnote 14 the use of alternative mechanisms of control in a state's repertoire, such as the administrative crackdown introduced in this paper, has not. Research on such alternative mechanisms has looked primarily at co-optation or surveillance, and with a focus on autocracies.Footnote 15 By examining the frequency and tactics of administrative crackdown, I show how democracies and autocracies alike design coercive institutions to facilitate nonviolent repression. This article is also unique in that instead of focusing on armed targets, it shows how states crack down even on nonviolent nonstate actors, such as domestic and international NGOs.

Second, in contrast to the influential work on transnational advocacy networks, I show that human rights victories and reforms resulting from local and international pressure may be short-lived. Implicit in both the boomerang and spiral models of NGO power is the core assumption that local NGOs are able to reach out to international actors for assistance.Footnote 16 While this assumption had a stronger empirical basis in the past, this article sheds light on the contemporary barriers to NGO mobilization. Instead of initiating long-term improvements in human rights when facing international pressure, states may be learning to counter these dynamics by ramping up repression.

The article proceeds as follows. First, I examine the rise of NGOs as important actors in contemporary global governance, and look at the main strategies of repression states can employ against these groups. I then lay out my theory and introduce an original data set on state repression of NGOs to test its hypotheses. A case from India sheds light on how and why the state adopted different crackdown strategies in response to immediate or long-term threats, and how these strategies differed between domestic and international NGOs. I conclude by discussing the implications of this crackdown for the use of civil society actors by the international community, as well as donors and citizens in the Global South.

Directing Aid to Civil Society Abroad

Both the absolute number and the influence of domestic and international NGOs have grown dramatically since the middle of the twentieth century.Footnote 17 This was due to both geopolitical changes and the emergence of a pro-NGO norm across the international system.Footnote 18 Since NGOs provided a number of political and economic benefits, many states have given these organizations wide access and participatory roles in recent decades.Footnote 19

Globally, a large amount of resources was channeled to NGOs because many donors—public and private alike—perceived them as more efficient than states in achieving certain goals. For instance, in countries with weak institutions and poor governance, direct aid transfers to states raised issues of misuse and bureaucratic inefficiency. Donors then specifically sought out NGOs for projects instead.Footnote 20 Being less bureaucratic and more nimble than state institutions, NGOs were seen as key agents of both development and democratization.Footnote 21

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Western governments also began spending more resources to promote democracy abroad, including, but not limited to, conditionality, diplomacy, and military intervention. Democracy assistance, or “aid programs specifically designed either to help non-democratic countries become democratic or to help countries that have initiated democratic transitions consolidate their democratic systems,”Footnote 22 was among the most visible facets of democracy promotion.Footnote 23 As part of this assistance, US administrations have allocated billions of dollars in foreign assistance each year. Much of this was spent on programs supporting democratic institutions, rule of law, and human rights, implemented via domestic and international NGOs.Footnote 24 These groups became the face of civil society for donors seeking to promote democracy.Footnote 25 As a result, NGOs in the global South were often targeted by foreign donors as visible, easy-to-reach organizations within civil society.

Strategies for Repressing NGOs

Authorities frequently engage in repression to counter ongoing challenges to the status quo. That is, dissent increases repressive behavior.Footnote 26 However, dissent and repression have an endogenous relationship: state authorities may engage in preventive repression to undermine or restrict dissent before it occurs.Footnote 27 In addition to undermining groups’ willingness to organize against the state, such preventive repression damages their capacity to impose costs.Footnote 28 As I show however, preventive repression is not synonymous with violent repression. Repression can also be carried out through administrative or nonviolent means. The causes and effects of what I call administrative crackdown have not been analyzed in great depth.

Existing studies on the determinants of state repression and control primarily look at the causes and consequences of state violence that is used to repress conventional challengers such as social movements,Footnote 29 opposition parties,Footnote 30 and dissidents,Footnote 31 with much less attention to state repression of NGOs. I focus on NGOs because of their centrality to contemporary global governance. Although their functions may sometimes overlap with broader civil society groups and social movements, NGOs are more institutionalized than other kinds of amorphous civil society organizations and thus may be easier to target. A focus on NGOs is valuable because states may repress nonviolent nonstate actors in ways that differ from those used against armed nonstate actors. However, NGO organizational structures and strategies are tied to national environments.Footnote 32 Beyond their internal organization, NGOs are shaped by the political structures and institutions with which they interact.Footnote 33 Ultimately, both domestic and international NGOs are governed by national laws, develop advocacy strategies in response to domestic political opportunities, and are shaped by powerful sets of social norms in their host countries. Although there is a growing number of studies on state–NGO dynamics,Footnote 34 this is the first paper to systematically analyze how states, once they decide to repress NGOs, choose between different crackdown strategies.

Repression is the use of coercive action against an individual or organization within the territorial jurisdiction of the state. Its purpose is to impose a cost on the target as well as to deter specific activities perceived to be challenging to state personnel, practices, or institutions.Footnote 35 I differentiate between violent or overt crackdown and nonviolent or administrative crackdown. Overt crackdown involves violence against NGO officials, including arrests, detention, extrajudicial killings, disappearances, and assassinations of organizational staff, volunteers, and activists. It also includes attacks on NGO offices and destruction of their property, and thus captures physical integrity rights violations. In contrast, administrative crackdown is the use of legal restrictions to create barriers to entry, funding, and advocacy by NGOs. This includes (but is not limited to) violations of civil liberties, such as the rights to free speech, assembly, association, and movement.Footnote 36

To be clear, not all NGO-related legislation is aimed at cracking down on these groups. Regulations may establish standards for appropriate organizational behavior and set penalties for legitimate violations. States frequently use regulations to routinize the behavior of NGOs. These regulations produce convergent practices and prevent malfeasance that threatens to undermine confidence in the entire NGO community.Footnote 37

However, I focus on the conditions under which states, when they decide to repress NGOs, use administrative crackdown (anti-NGO laws) as a strategy. Unlike regulation, administrative crackdown is intended to impede the larger NGO community, through barriers to entry, funding, and advocacy. Barriers to entry means the use of law to discourage, burden, or prevent the formation of NGOs. Such laws increase the complexity and difficulty of the registration process, expand state discretion in denying permits, and prevent appeals.

Barriers to funding impose restrictions on how NGOs secure financial resources. States impose restrictions based on the origin of the funds, how those funds are channeled, and what purposes they can be used for. Restrictions on foreign funding are worrisome because many NGOs in the Global South depend on funds from abroad. Local groups tackling contentious issues may not be able to raise funds domestically.Footnote 38 Even local philanthropists may be deterred by poor tax incentives or a fear of retribution.Footnote 39

Finally, barriers to advocacy restrict NGOs from engaging in the full range of free expression and public policy advocacy. They prevent legitimate activities by making certain forms of speech, publication, and activity illegal. Many countries also implement laws that ban NGOs from working on “political” issues. The word political in these laws is intentionally left vague, providing cover for states to crack down on NGOs they perceive as politically threatening.

Choosing Between Different Repressive Strategies

When confronted with threatening NGOs, states decide whether to accommodate them or repress them. Some states may decide to accommodate or tolerate their presence in the country, owing to the multitude of economic, technocratic, and service-provision benefits they provide.Footnote 40 However, it is clear that some states are not willing to tolerate at least some of the NGOs operating within their borders. Whether a state chooses violent or administrative crackdown depends, I argue, on its short-and long-term strategic goals.

To understand the causes and strategies behind state repression of NGOs, scholars have recently begun documenting trends, making important theoretical and empirical contributions in a burgeoning area of study.Footnote 41 For example, some studies have found that states perceive foreign aid to NGOs as supporting the regime's political opponents.Footnote 42 In these circumstances, states may choose to forego the benefits accrued from foreign-funded NGOs and adopt restrictive financing laws. Regimes that have recently experienced competitive elections are particularly likely to crack down on foreign aid to local NGOs as political opponents may seek to discredit the incumbent's victory and states perceive a window of opportunity to crack down on these opponents.Footnote 43 Most recently, scholars have argued that when states continue to commit severe abuses and have also ratified human rights treaties, they impose restrictions on human rights organizations to avoid monitoring and hide their noncompliance.Footnote 44

A large focus of this work lies in explaining the onset of legal restrictions, rather than variation in the type of laws, or repressive strategies, states employ to target NGOs. Moreover, the analysis is confined to democratizing low-and middle-income countries,Footnote 45 or to NGOs working in specific issue areas.Footnote 46 Instead of the narrower focus on the onset of restrictive foreign financing laws (one form of what I term administrative crackdown), I examine the variation in the type of crackdown (that is, violent or administrative). Empirically, I also expand the focus to include all countries.

I argue that violence is more useful in the context of ongoing domestic threats such as protests, since it addresses the short-term strategic goal of ending such threatening mobilization. But in addition to its punitive and deterrent effects, violence can have adverse consequences. Regimes may refrain from using violence against nonviolent mobilizations for fear of defection.Footnote 47 And even if the state orders violent crackdown, state agents might refuse.Footnote 48 Violence may also intensify mobilization against the regime. Research has shown that publics are more likely to approve of abuses targeted at violent opposition movements.Footnote 49 However, given that NGOs are nonviolent in nature, violently cracking down on them can alienate the population.

If violence is easily linked to the state or its agents, it also increases the state's risk of criminal liability. Since the 1980s, there has been a dramatic increase in criminal accountability of state officials for the past use of violence, in both international and domestic judicial processes.Footnote 50 These prosecutions of military, civilian, and political leaders can increase the perceived costs of repression.Footnote 51 Thus, state agents may be deterred from using violence due to a mix of normative pressures and material punishments. However, not all states have the same attitudes to the use of violence. Besides institutional features that protect organizations against repression, there are normative reasons why states may differ. The strong presence of the rule of law, combined with preferences for less coercive means, may lead some states to be more likely to use administrative means rather than violence to deal with opponents.

Violence against NGOs can also have adverse international consequences. It may violate human rights treaties and preferential trading agreements that contain human rights clauses.Footnote 52 Compared to local NGOs, targeting INGOs is especially risky since they often have the legal and political backing of their home states.Footnote 53 It can also be risky for states that are dependent on INGOs for service provision and transfer of aid. Finally, the use of violence requires knowledge of specific actors and organizations to target, information which is sometimes costly and difficult to acquire. Therefore, states may prefer strategies that prevent NGOs from posing challenges in the first place.

Administrative crackdown is one such strategy. In the short term, it may not be attractive because it requires time, effort, and resources. In democracies or states with democratic trappings, legislators have to go through the process of drafting bills, debating provisions, and collecting sufficient votes on a bill before it can be adopted as law. However, in the long term, it has advantages over the use of violence. Because laws seem ordinary, routine, and apolitical to many, they are more likely to be perceived as regulation rather than crackdown. Indeed, coercion can be “costly, crude, and potentially dangerous for authorities.”Footnote 54

Compared to violence, administrative crackdown is also less likely to invite international condemnation. When states repress groups administratively, they rarely face tangible consequences beyond minor public expressions of disapproval.Footnote 55 It can also deter collective action from coalescing in the first place. Aleksandr Tarnavsky, sponsor of Russia's 2015 “undesirable organizations” law, argued that it would be a “weapon hanging on the wall … that never fires” but stands as a warning to potentially uncooperative NGOs.Footnote 56 Thus administrative crackdown has some advantages over violent crackdown in the long term.

While the foregoing argument applies to both domestic and international NGOs, they are not entirely interchangeable. They represent different threats to states because they have different primary audiences. NGOs can direct their programming to locals, domestic elites, or international elites.Footnote 57 While both domestic and international NGOs may target all three of these constituencies, INGOs are inherently better at targeting other states, intergovernmental organizations, and transnational networks. INGOs disseminate information more effectively, and transnational advocacy networks can pressure governments to reform.Footnote 58 Access to Western forums is also critical to the success of local challengers, and INGOs can lend legitimacy to local grievances.Footnote 59 Negative reports by INGOs can also impair the shamed country's access to aid, trade, and foreign direct investment.Footnote 60 Since INGOs are better able to target international audiences and impose costs on states from above, states may feel more threatened by their activities.

These differences in audiences might lead states to crack down on domestic and international NGOs differently. Violence against domestic NGOs may go unnoticed internationally, but violence against INGOs is likely to be reported. Since such reports can have negative repercussions internationally, states may prefer to use administrative crackdown with INGOs.

Testable Implications: How Do States Repress NGOs?

Here I explore when NGO activities pose immediate or long-term threats to states, and how states consequently decide to use violent or administrative crackdown strategies against costly NGOs.

Influencing Electoral Politics

NGOs undertake multiple activities that can influence electoral politics and contribute to democratization. As Donno points out, “democratization involves a change in the quality and conduct—not necessarily the outcome—of elections.”Footnote 61 Even if multiple political parties exist and electoral competition is high, it does not necessarily mean that competition between parties is free and fair, which is essential for democratization. NGOs can be critical to improving both the quality and the conduct of elections. These organizations educate the public about their rights, organize “get out the vote” campaigns, monitor the transparency of the electoral process, and promote equal media access and electoral integrity.Footnote 62 INGOs also often carry out political party training to strengthen party development in transitional countries.

By improving both the quality and the conduct of elections, NGO activities may help make opposition parties more competitive, threatening the incumbents. They can also call out electoral manipulation by incumbents. Reports of fraud by election-monitoring NGOs can threaten the numerous international benefits that accompany democratically certified elections.Footnote 63 Fraudulent elections also serve as focal points for citizens to collectively organize around; scholars have found that protests are more likely to occur and persist following negative reports from international observers.Footnote 64

In many countries, civil society activists or NGO leaders run for election. On occasion, NGOs may also transform into political parties.Footnote 65 With their prior support in the population and their organizational structures and resources, such groups can quickly upset the status quo. This may especially be the case in democratizing states where a multitude of parties exist. In Malaysia, for instance, after gradual electoral activism by NGOs, a number of NGO activists were candidates in the 2008 elections, and many succeeded in their bids.Footnote 66 In doing so, they reasoned, “We can't leave politics to the politicians … It is too important … We campaign on issues that the mainstream political parties will not touch.”Footnote 67

Even when political parties can compete freely, casting NGOs as “foreign agents” and linking their activities to foreign governments—whether the connections are real or perceived—can reduce their popularity. As discussed earlier, there is a growing donor preference for channeling aid via NGOs rather than official institutions. But states may be hesitant to allow cross-border transfers of money into their territory when they cannot directly monitor such funds.Footnote 68 Even if an NGO does not pose much of a threat to the state, the political leverage obtained by portraying it as a foreign agent might be helpful to the state. Indeed, a heavy international-aid footprint may be unpopular and delegitimizing for political leaders.Footnote 69 Christensen and Weinstein have argued that “where foreign donors are unpopular, leaders can realize a domestic political payoff by limiting donors’ influence—real or perceived.”Footnote 70 While these findings are based on limited public opinion data, they nevertheless point to another mechanism explaining why states seek to crack down on NGOs during electoral periods.

Since NGOs can aid the democratization process, potentially mobilize populations against the incumbent, and declare elections fraudulent, I argue that states are likely to crack down on NGOs when electoral competition increases. However, because these threats are long term rather than immediate, states will be likely to use administrative rather than violent forms of repression.Footnote 71

H1 When electoral competitiveness increases, states are significantly more likely to adopt a strategy of administrative crackdown against NGOs.

Aiding Domestic Mobilization

NGOs also have the potential to aid mobilization, which can subsequently threaten a state. NGOs can promote moderate political participation by means such as voting only in democracies when institutions are working quite well.Footnote 72 In poorly functioning democracies, people are less likely to see voting as an effective means of communicating their preferences, and NGOs are more likely to adopt contentious tactics such as protests.

NGOs facilitate this collective action by bringing resources (financial, educational, and infrastructural) to communities.Footnote 73 Studies have found that the presence of NGOs either in a state or in its geographic neighborhood increases the number of nonviolent, anti-government protests.Footnote 74 Actors such as NGOs, which use nonviolent action, often also receive greater resources and assistance from foreign governments, international organizations, and foundations.Footnote 75 State elites may fear that given NGOs’ ability to attract funds, they can train sizable parts of the population in protest techniques. For instance, in Serbia, US democracy aid reached a total of USD 50 million in 2000. A large part of these funds went to the student group Otpor, which led the grass-roots campaign of opposition to the Serbian regime.Footnote 76 Otpor later went on to train the leaders of the Rose Revolution in Georgia.Footnote 77 The US government also spent millions of dollars on democracy assistance to Kyrgyzstan in 2004, just a year before its revolution.Footnote 78

In the face of ongoing domestic threats, states will be more likely to crack down using violent rather than administrative means, since these can be immediately implemented. Even if states want to implement administrative crackdown to prevent future threats, this strategy may use limited critical bureaucratic and material resources. These resources could instead be used to respond to the immediate short-term threat of mobilization through violence. This may especially be the case as mobilization increases and the resulting information cascade persuades more people to join protests and show their dissatisfaction. In such a scenario, even states that had been devoting resources to multiple crackdown strategies may need to instead channel all resources to violence to stop the immediate threat.

The choice to avoid immediate implementation of administrative crackdown when faced with protests can be seen in the case of the color revolutions. While techniques for controlling civil society networks were pioneered in the region in 2001, it was not until 2005 to 2006 that there was an increase in administrative crackdown on NGOs in the region.Footnote 79 The Duma deputies who introduced the infamous “foreign agent” law in Russia specifically envisioned it as a “barrier to the spread of the revolutionary contagion.”Footnote 80 Similarly, Belarussian president Aleksandr Lukashenko insisted, “In our country, there will be no pink or orange, or even banana revolution. All these colored revolutions are pure and simple banditry.”Footnote 81 He subsequently enacted administrative crackdown measures that liquidated political NGOs and NGOs with access to foreign technical assistance. While administrative crackdown could have been introduced during the color revolutions, it was not until afterward that these states devoted resources to prevent NGO networks from mounting longer-term threats in the future.

H2 When mobilization increases in a state, it is significantly less likely to adopt administrative crackdown and more likely to adopt violent crackdown against domestic NGOs.

State Economic Interests

NGOs offer a number of economic benefits to states through their service provision. This is especially the case when states are unable to provide services on a regular and consistent basis.Footnote 82 States often claim credit for these services.Footnote 83 However, NGOs can also impose significant economic costs on a state. They can threaten the state's implementation of its industrialization policies, question the nature of its control over natural resources, and advocate for a more equitable distribution of wealth and resources. We often see this with large infrastructure projects that threaten the environment, displace populations, or harm indigenous workers. Advocacy NGOs may also influence potential donors to a state's development projects. When these projects have environmental consequences that have not been accounted for, lobbying by these NGOs may reduce donor contributions. Thus, states may find environmental NGOs costly if they perceive that such groups threaten their access to resources.

However, the state will not always crack down on such groups. I argue that crackdown is conditional on the state's vulnerability to international pressure. Such pressure is more effective when it has tangible consequences, such as the withdrawal of bilateral aid, official development assistance, or private aid.Footnote 84 INGO shaming of recipient governments, especially states that are not major powers, also leads donors to redirect aid away from state institutions and toward NGOs.Footnote 85 Therefore, states may refrain from cracking down on NGOs to avoid being punished by aid withdrawal.

But even aid-dependent and poorer states may hesitate to jeopardize NGO services, making them less likely to crack down on NGOs. For instance, Kyrgyzstan's parliament tried to pass a bill similar to Russia's 2012 “foreign agent” law, but the bill was defeated in 2016. Kyrgyz legislators who voted against the bill cited the need for foreign funding: “We get financial assistance from [international organizations] in many fields including healthcare, education, and agriculture among others. We need this money.”Footnote 86

Aid is also crucial for states with ongoing armed conflicts who depend on humanitarian INGOs for goods and services. To avoid losing access to aid altogether, states may prefer to avoid certain administrative crackdown tactics, such as barriers to foreign funding. However, they may still be open to using other tactics of administrative crackdown, such as barring NGOs from political activities. This ensures that the country still has access to aid, while hobbling NGOs that engage in contentious programming.

H3 States that depend on Western bilateral aid and official development assistance are less likely to use administrative crackdown against NGOs in their territory.

Data and Estimation

To quantitatively test my three hypotheses, I use panel data from 1990 to 2013. To address a common critique of this vein of empirical work—namely, that statistical association does not provide proof that the results are a product of the postulated mechanisms—I provide a case study from India. The country used both violent and administrative crackdown against NGOs and was a pioneer of the latter starting in the 1970s. A qualitative case study can also provide insight on how states decide to respond to NGOs depending on the nature of the threat they pose (immediate or long-term), and how the choice of crackdown strategy might depend on whether the NGO is domestic or international. Interviews with state officials allow me to further pin down the strategic logic behind why states might use one repressive strategy or another.

Scope Conditions

The analysis looks at repression of NGOs since the end of the Cold War across all countries (excluding micro-states, or states with a population of less than 500,000). The expansion of democracy assistance since 1990 means that the amount of assistance being channeled to NGOs is radically larger and more consequential than during the Cold War. Previous studies have shown that 1990 is often considered a watershed year in democracy assistance.Footnote 87 Also, there is little data on state policies toward NGOs and on amounts of types of aid channeled to countries before 1990; this makes it difficult to test my theory before 1990. The measures described in the next section incorporate crackdown on both domestic and international NGOs.

Dependent Variables and Descriptive Statistics on Administrative Crackdown

The two main variables of interest are violent and administrative crackdown. To measure violence, I use variables from the Ill-Treatment and Torture Data Collection Project, which codes allegations by Amnesty International of state ill-treatment and torture from 1995 to 2005.Footnote 88 This data set disaggregates the responsible state agents as well as the alleged victims. Specifically, the variable victim type codes victims of violence as “criminal,” “dissident,” “marginalized individual,” or “unknown,” and is operationalized as a count variable. I use the “dissident” category in my analysis because this refers to NGO activists, human rights defenders, and prisoners of conscience, so it is the concept most closely aligned with the population under analysis here.

I use a second variable from the data set, agency of control, to focus on attacks on dissidents by state agents, excluding big businesses and criminals. I also update the data set to 2013, specifically the count of dissidents attacked by state agents (as conceptualized in the original coding), to match the rest of the data used in the study. I use the same documents that were used in coding the Ill-Treatment and Torture data: Amnesty International's annual reports, press releases, and action alerts.

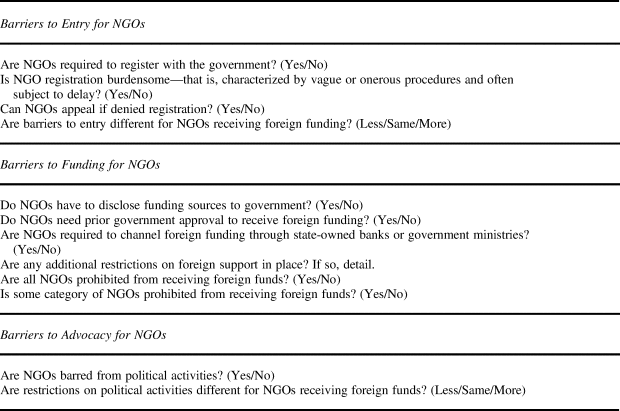

For administrative crackdown, I code laws representing barriers to entry, funding, and advocacy for NGOs.Footnote 89 These variables were coded from a variety of primary (legislation) and secondary sources produced by the International Center for Not-for-Profit Law, the USAID Civil Society Organization Sustainability Index, the USAID NGO Sustainability Index, NGO Law Monitor, and CIVICUS.Footnote 90

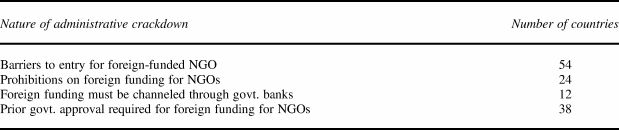

I coded administrative crackdown measures under three major categories, summarized in Table 1. These data offer a number of advantages over previously available data, which is more limited in its spatial and temporal scope,Footnote 91 looks at NGOs working only on certain kinds of issues,Footnote 92 excludes consolidated democracies or aid-providing countries, and looks at only specific types of administrative crackdown measures, such as restrictive foreign-financing laws.Footnote 93 Other available data do not distinguish between various forms of state repression of NGOs.Footnote 94 While these projects have laid important groundwork for documenting state crackdown on NGOs, the extended data presented here cover all countries and multiple strategies of repression, providing significantly greater leverage. They also offer a better match between theory and empirics, as state repression of NGOs is a global phenomenon that transcends regional boundaries, regime type, and levels of economic development. Thus the data presented here support a more comprehensive assessment of this topic globally, including multiple state crackdown strategies and a broader range of NGOs likely to be subject to it.

Table 1. Coding rules, administrative crackdown

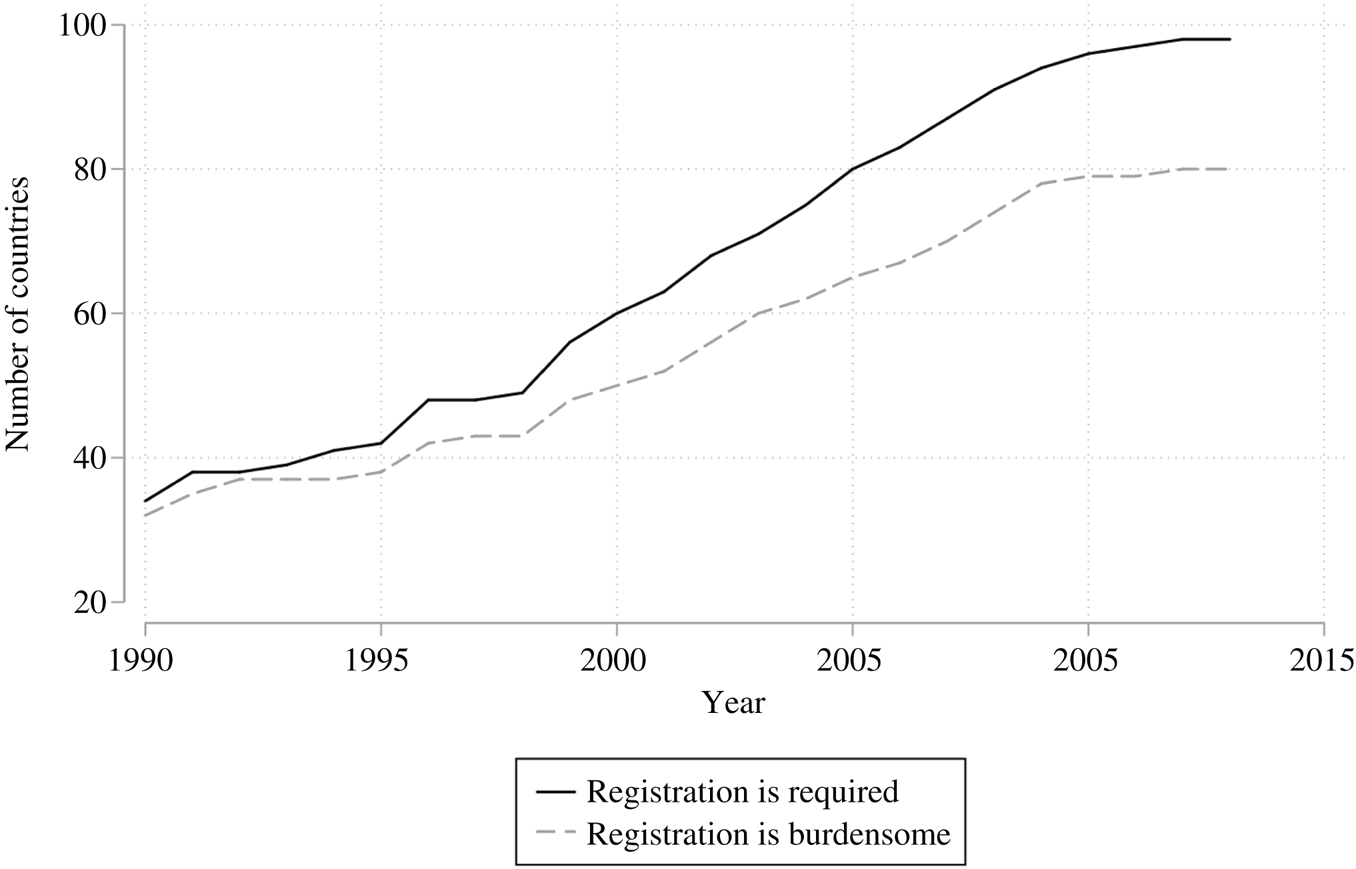

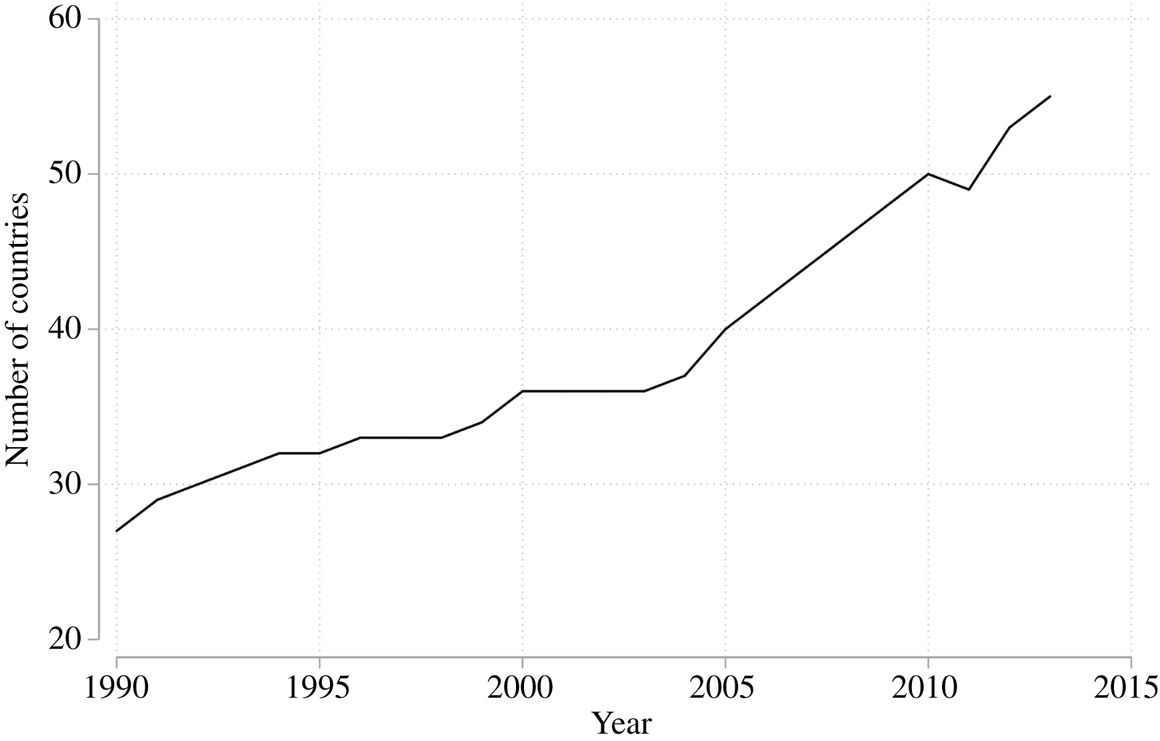

For barriers to entry, as a baseline regulation, I first look at whether states require mandatory registration for NGOs operating in their territory. Burdensome registration is coded as 1 if the process includes vague criteria for registration, a requirement to register every year, permission to operate only in certain issue areas, lengthy wait times, or unreasonable founding requirements in terms of number of members or initial funds. I also code dummy variables for whether a NGO can appeal if denied registration and whether barriers to entry are different for NGOs receiving foreign funding. The number of countries making it mandatory for NGOs to register has been steadily increasing, along with the number of countries where this process also places a high burden on NGOs (Figure 2). While the former can be conceived of as potentially harmless regulation, the latter constitutes crackdown.

Figure 2. NGO registration requirements, 1990–2013

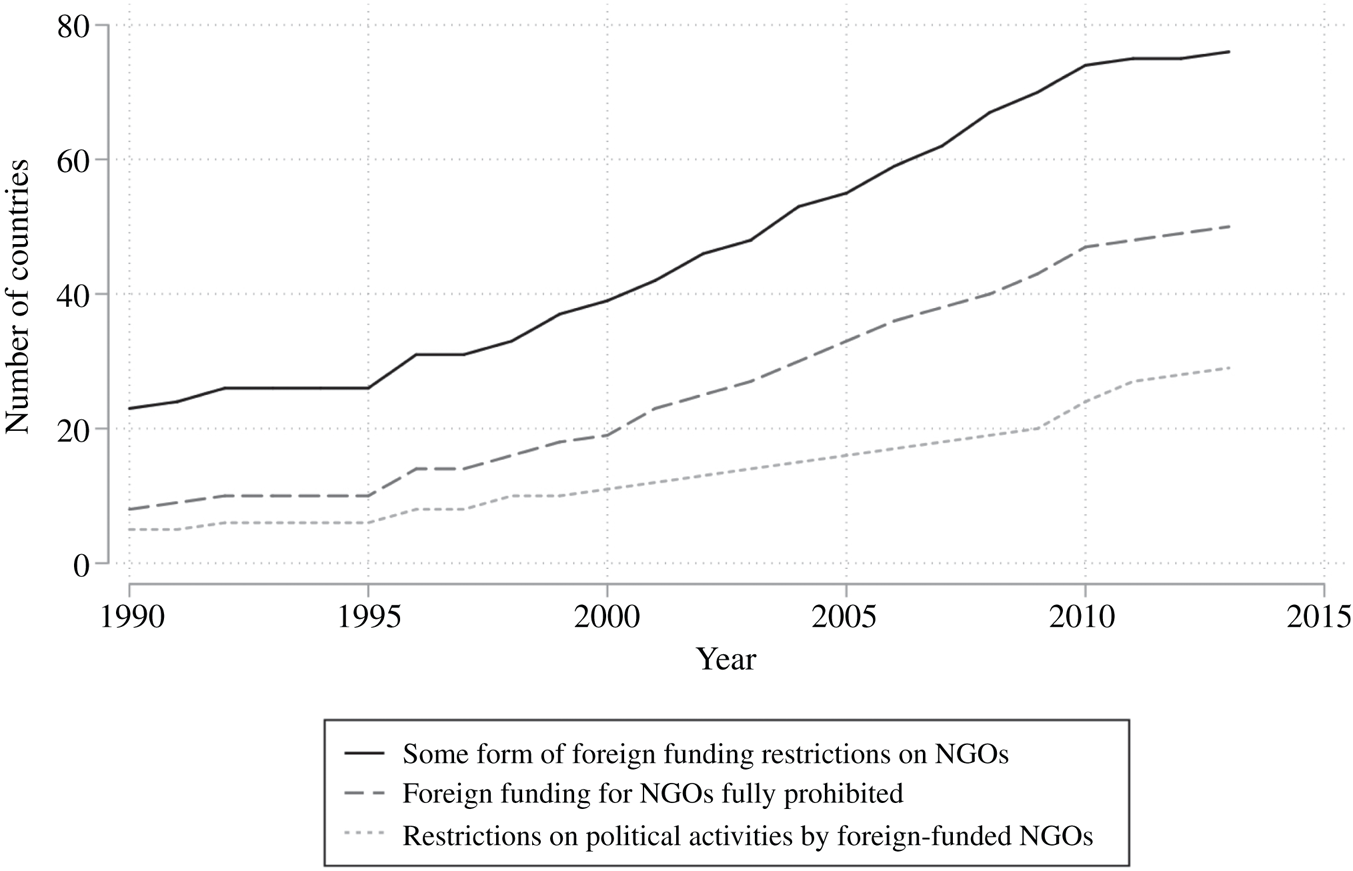

In creating barriers to funding for NGOs, states can block foreign funding for NGOs completely or partially. They can impose restrictions on NGOs based on the origin of funds, how those funds are channeled, or which issues these funds can be channeled to. Figure 3 and Table 2 show the nature and growth of such administrative crackdown tactics. Additional measures against NGOs vary by country and include limiting foreign NGOs’ number of foreign employees, imposing travel restrictions on employees of foreign NGOs, requiring prior approval for participation in international conferences, and restricting association with foreign NGOs.

Figure 3. Restrictions on foreign funding for NGOs, 1990–2013

Table 2. Barriers to funding for NGOs, 1990–2013

Finally, I analyze barriers to advocacy for NGOs. I first look at whether countries restrict NGOs’ political activities (Figure 4), and second, whether these restrictions differ for NGOs receiving foreign funds.

Figure 4. Laws restricting NGOs’ political activities, 1990–2013

The figures show that states have increasingly used such strategies over time. This may be because initial democracy assistance in the early 1990s was directed toward small-scale NGO initiatives lacking coherence. Therefore, these organizations were never perceived as challenging state interests. However, this perception changed with the overthrow of the Milošević regime and the success of the color revolutions, aided by Western NGOs.Footnote 95

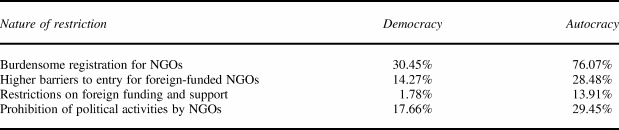

Table 3 and Figures 5 and 6 disaggregate how administrative crackdown measures are distributed across democracies, autocracies, and hybrid regimes.Footnote 96 Democracies typically implement fewer such crackdowns than autocracies do, with the exception of restrictions on political activities by NGOs. This could be because of the nature of the threats NGOs pose to these states, as well as the varied state reactions to these NGOs. Many democracies have well-established institutional mechanisms for accommodating the demands of citizens, which may lead to fewer threats from societal groups. Besides institutional features, normative reasons such as regularized interaction among citizens and elites and frequent compromises promoting a peaceful norm of conflict resolution may also reduce the number of serious challenges from NGOs, which impacts the choice of whether to repress these organizations. However, as in any bivariate comparison, there may be a host of other factors driving this relationship, which I explore in the next section.

Figure 5. Barriers to foreign funding for NGOs by type of regime, 1990–2013

Figure 6. Barriers to political activities by NGOs by type of regime, 1990–2013

Table 3. Administrative crackdown by regime type (country-years), 1990–2013

Independent Variables

The main independent variables of interest are levels of electoral competition and levels of domestic mobilization. Electoral competetiveness measures legislative electoral competition and is an ordinal scale from 1 to 7.Footnote 97 This variable captures whether elections are allowed, whether opposition is allowed and multiple parties are legal, whether parties stand an actual chance in elections, and how close elections are. At the lowest level, 1 captures unelected leaders and legislatures where there is no real competition, and at the highest level, 7 captures a system that has multiple parties and close elections, with the largest party getting less than 75 percent of the vote. Domestic mobilization is operationalized as protest levels, which measures the total number of nonviolent and anti-government protests per country-year, as identified by the Cross-National Time-Series Archive.Footnote 98

To measure vulnerability or susceptibility of a state to international pressure, I use logged (and lagged) development aid from the United States, European Union, and other countries in the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development's total bilateral aid and official development assistance.Footnote 99 dependence on aid is measured as aid as a percentage of GDP.

Control variables include a polity variable from the Polity IV database,Footnote 100 and GDP data from the World Bank (constant 2005 dollars), which is both lagged and logged. I use the Political Terror Scale as a control for overall repression in the state.Footnote 101 The Political Terror Scale is an ordinal scale from 1 to 5 for the levels of political violence and terror a country experiences in a given year, with 1 being the lowest and 5 being the highest. civil war is measured using data from UCDP/PRIO's Armed Conflict Database,Footnote 102 and population (logged) is coded from the World Bank's World Development Indicators.

The models also control for neighborhood effects, or the percentage of countries in a geographic region that have adopted administrative crackdown measures on NGOs, such as restrictions on foreign funding or political activities.Footnote 103 I anticipate regional effects for administrative crackdown rather than violence because countries may not be able to violently crack down on potential threats due to its adverse consequences. INGOs perceived as threatening may not even be present in the country. Even for domestic NGOs, states may not have knowledge about the right targets. On the other hand, administrative crackdown may prevent costly NGOs from posing a threat or even entering the country in the first place. By erecting legislative barriers that constrain the activities of both local and international NGOs and prevent international actors and their resources from reaching the country, states can push back against democracy promotion.Footnote 104

Estimation

The prior section looked at a variety of tactics of administrative crackdown. Many argue that these different restrictions are functionally equivalent from a repressive point of view.Footnote 105 However, for the models that follow, I focus on two tactics of administrative crackdown in particular as the main dependent variables: barriers to foreign funding for NGOs and whether NGOs are prohibited from political activities. These two tactics are perceived as most concerning in existing policy discussions.Footnote 106 Disaggregating these two also allows us to see whether states are significantly more or less likely to use one or the other when faced with threats. However, the online supplement also provides models for assessing the probability of states’ using other tactics of administrative crackdown as dependent variables.

All models looking at administrative crackdown as the outcome variable (whether barriers to foreign funding or political activities) are binary logit with a random effects specification. However, the coefficients for a logistic regression do not have a simple translation. To make these results more interpretable, I also show predicted probability graphs for the relevant variables.

The models use a random effects rather than a fixed effects specification because random effects are better at estimating both the between-and within-unit effect, whereas fixed effects prioritizes the within-unit variation.Footnote 107 Given that countries may not be cracking down on NGOs independently of one another and that the models include a variable on neighboring effects to account for that, a fixed effects model would throw away all the variation across countries. Thus the contextual and temporal structure of the data necessitates a random rather than a fixed effects model. The models also include temporal controls in the form of lagged independent variables. There are both theoretical and statistical reasons to expect that the effect of explanatory variables such as protest levels, dependence on foreign aid, and regional patterns of NGO crackdown might operate with a lag.Footnote 108

In addition to analyzing different tactics of administrative crackdown, I construct a comprehensive index of obstruction, which includes the various forms of administrative crackdown described in the previous section. As shown in Table 1, this includes ten different indicators. This index of obstruction uses an ordinal scale from 0 to 10, with 0 implying no administrative crackdown measures and 10 indicating that all measures were present in a given year. Since the index is a discrete count variable, I use a negative binomial regression model to test the conditions under which states are more or less likely to enact these measures.Footnote 109

Since state crackdown on NGOs using violence is available as count data, I first check whether I should employ the zero-inflated Poisson model or the negative binomial model. Since the count data has an excess of zeros and is also over-dispersed, I use a zero-inflated Poisson model with a random effects specification while looking at the use of violence as the dependent variable.

Results

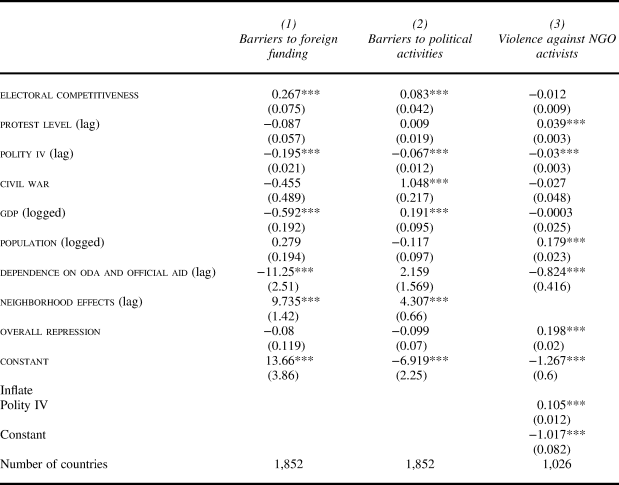

Table 4 looks at states’ use of violent or administrative crackdowns against NGOs. The first and second models look at the use of different types of administrative crackdown, while the third model looks at the use of violence. My argument suggests that, on average, states perceive NGOs as costly when they have the potential to challenge the status quo, especially during electoral periods. Consequently, states are more likely to implement administrative crackdown against these costly NGOs. However, when faced with ongoing protests, states are, on average, more likely to use violence rather than administrative crackdown, since the former can be implemented immediately.

Table 4. Crackdown against NGOs, 1990–2013

Notes: Results in columns (1) and (2) are based on a logistic regression, while those in (3) are based on a zero-inflated Poisson model. Robust standard errors in parentheses. * p < .10; ** p < .05; *** p < .01.

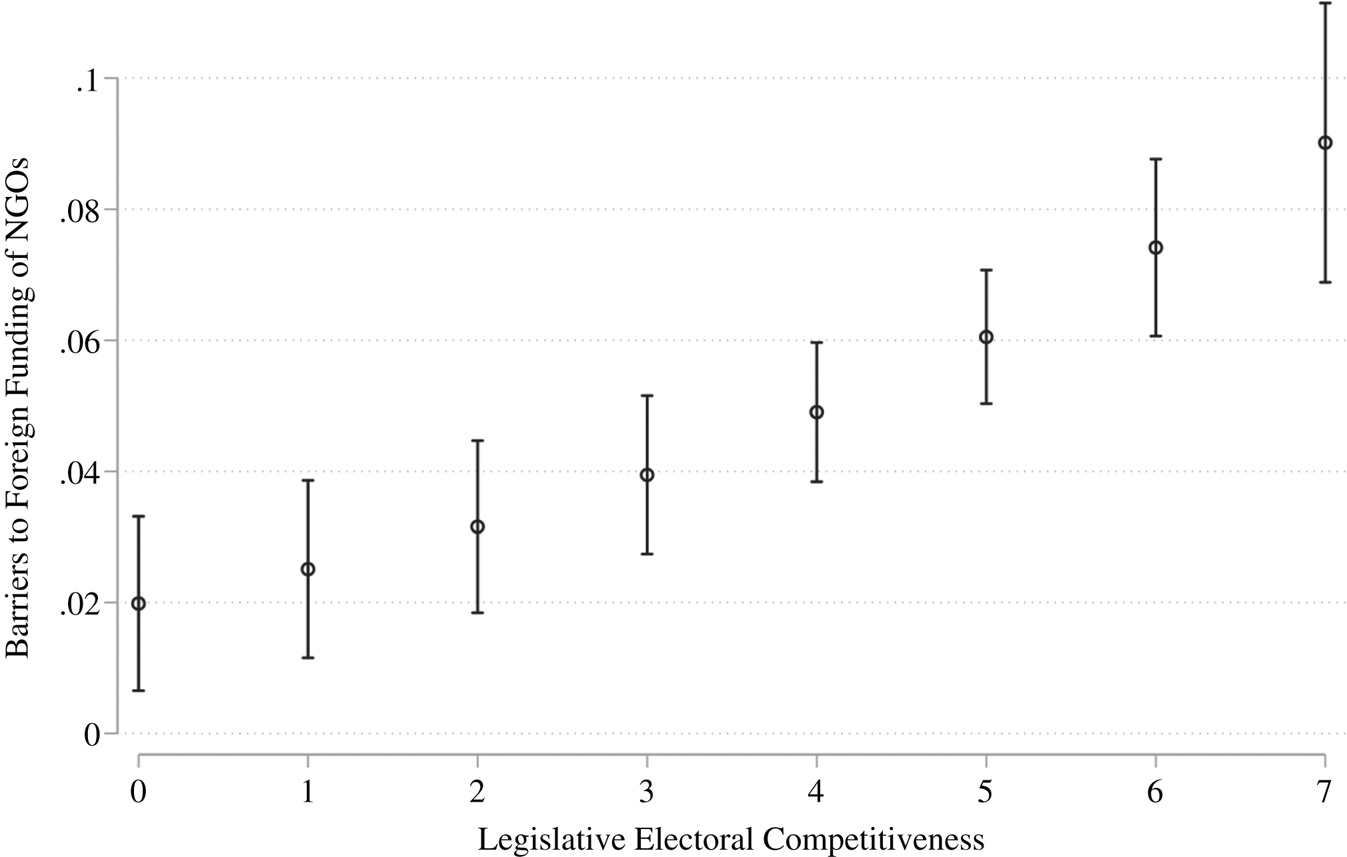

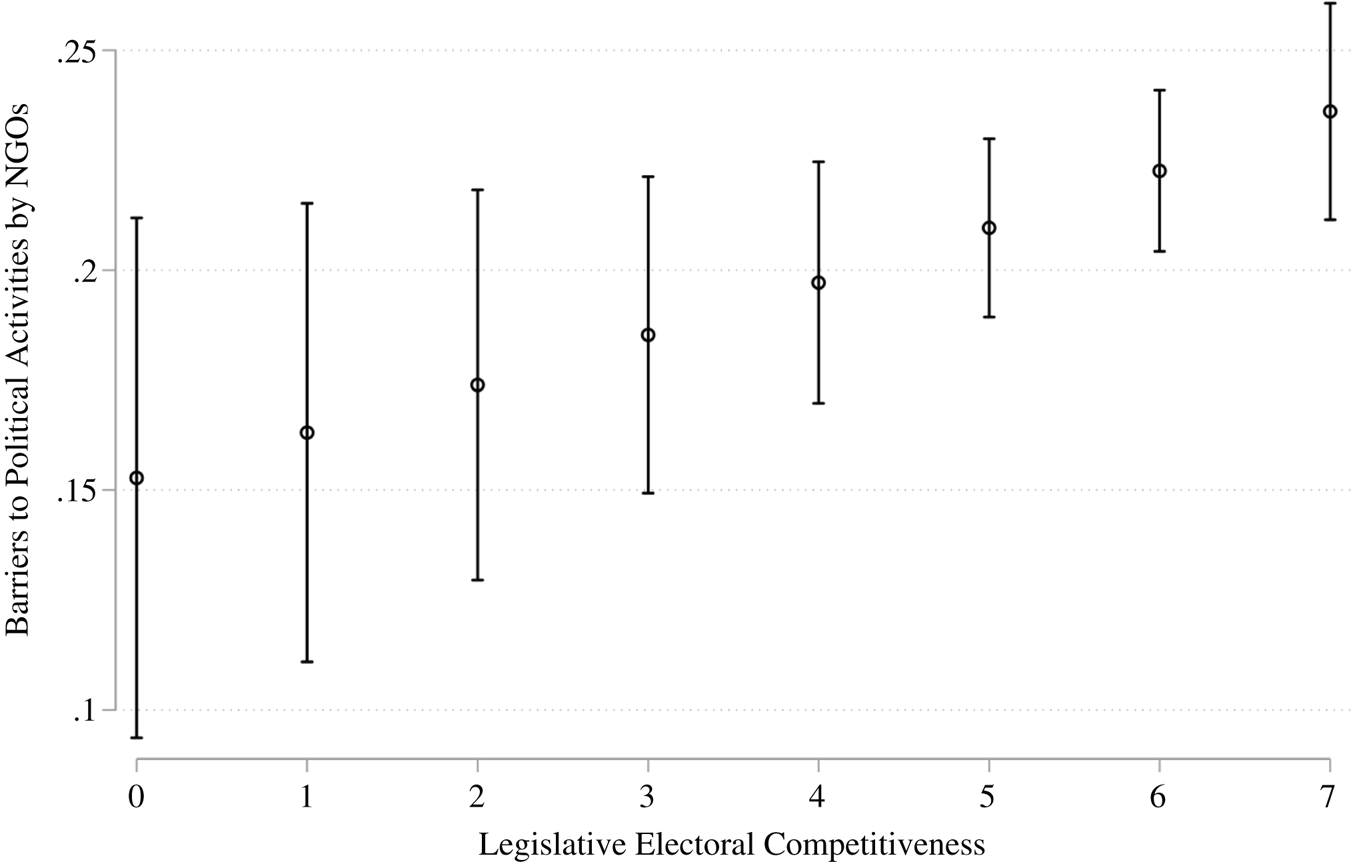

The logistic regressions in columns (1) and (2) show that increases in legislative electoral competitiveness are positively and significantly associated with a strategy of administrative crackdown against NGOs. This includes increasing restrictions on foreign funding for NGOs as well as on political activities by NGOs.Footnote 110

Figures 7 and 8 present the predicted probability of administrative crackdown as electoral competition increases. The predicted probability of state adoption of foreign-funding restrictions on NGOs increases with electoral competition. The confidence intervals overlap in some cases, but this does not mean that the results are statistically indistinguishable. To determine the likelihood that the true values of the differing levels of electoral competition occur simultaneously in the overlapping tails, I carry out post-estimation tests. The increase in the likelihood of adoption of such laws is significant, whether in terms of levels of competitiveness 0 to 4, or 4 to 7 (both at p < 0.01).

Figure 7. Predicted probability of barriers to foreign funding for NGOs, contingent on legislative electoral competitiveness, 95% CI

Figure 8. Predicted probability of limitations on “political activities” by NGOs, contingent on the level of legislative electoral competitiveness, 95% CI

Similarly, the predicted probability of state adoption of restrictions on political activities by NGOs increases with legislative electoral competitiveness (Figure 8).Footnote 111 According to the post-estimation tests just described, the increase in the likelihood of adoption of such laws is significant, whether in terms of levels of competitiveness 0 to 4 (p = 0.015) or 4 to 7(p = 0.04). These results suggest that states are using administrative crackdown to preempt challenges during electoral periods. It also lends support to recent findings by scholars that anti-NGO laws give advantages to incumbents in future electoral contests.Footnote 112

Neighborhood effects is also positively and significantly correlated with the use of barriers to foreign funding and political activities in a given year (Table 4). This suggests that states are learning from or emulating the administrative crackdown measures of other countries in the same geographical region. A state is more likely to prohibit foreign funding of NGOs if it is in a region where a higher percentage of states have adopted such prohibitions (model 1). The same holds for prohibition of NGOs from political activities.

There is also qualitative evidence of this trend. Through textual comparison of anti-NGO laws in the Middle East and sub-Saharan Africa, recent work finds evidence of NGO legal provisions being drawn almost verbatim from other countries. These similarities were “heavily geographically determined, moving between countries that either share a border or are in close proximity to each other.”Footnote 113 This dynamic can also be seen in the color revolutions, where “in their efforts to prevent a future color revolution, rulers learned not only from countries that experienced one, but also from countries that avoided having a color revolution.”Footnote 114 Many leaders in Central Asia learned the benefits of tightly controlling NGOs and foreign influence from Russia.Footnote 115 As a result, states in the region not only adopted administrative crackdown measures when others in the region did so, but even copied the most useful elements of these laws.Footnote 116 The evidence thus suggests that states are learning to navigate potential threats from their regional environment.

These results are also robust to using various other forms of administrative crackdown as outcome variables. This includes preventing appeals from NGOs that have been denied registration, requiring approval from the state before accepting foreign funding, and requiring NGOs to channel funds through state ministries or state-owned banks.Footnote 117 This provides evidence that, on average, electoral competitiveness directly affects states’ decisions to undertake administrative crackdown on NGOs.

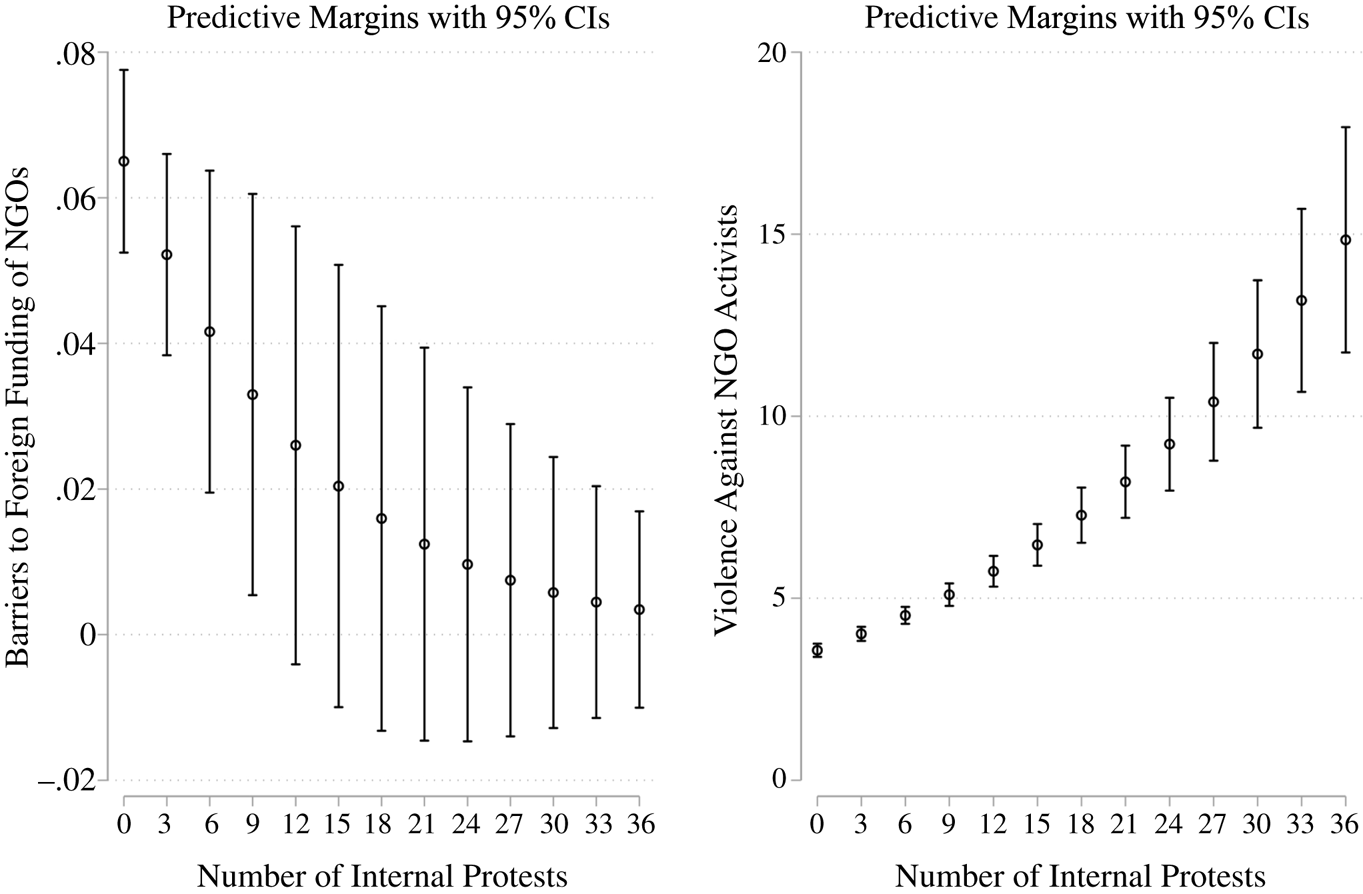

NGOs may also threaten states due to their mobilization of local populations. However, in view of the time it takes to implement administrative crackdown, H2 argued that states may not always employ that strategy during protests and would be more likely to use violent crackdown. I find that increasing protest is negatively associated with states’ use of administrative crackdown and positively and significantly associated with violence against NGOs and activists (Table 4). Prior scholarship finds that states are more likely to repress dissent as it becomes more violent.Footnote 118 However, the finding that even NGOs evoke such repressive responses from states is notable, because these groups are inherently nonviolent actors.

The predicted probability of both violent and administrative crackdown (through barriers to foreign funding) on NGOs increases with the number of protests in a year (Figure 9). The likelihood of administrative crackdown on NGOs falls as the number of protests in a given year increases. On the other hand, the probability of violence against NGOs increases as the number of protests increase, whether from 0 to 3, 3 to 9, 9 to 15, or 27 to 37 events (all at p < 0.01).

Figure 9. Predicted probability of state repression of domestic NGOs through violence or administrative crackdown, contingent on the level of protest in the country.

That the number of protests is positively and significantly associated with the use of violence suggests that as more individuals participate in protests, states reassess their strategy. They may shift their limited resources from administrative crackdown to violence. The downside of using administrative crackdown against increasing mobilization is that it can use up material and bureaucratic resources that are needed for violent crackdown. Thus states may be making trade-offs when choosing a crackdown strategy, depending on the nature and timing of the threat.

Turning to the effect of international vulnerability on state propensity to repress NGOs, we find that state dependence on foreign aid and official development assistance is negatively and significantly associated with states’ use of barriers to foreign funding for NGOs (Table 4). However, it is not significantly associated with the use of barriers to political activities by NGOs.

As dependence on foreign aid increases, why do restrictions on foreign funding go in the expected negative direction, while barriers to political activity do not? The former is expected because donors prefer channeling funds directly through nonstate organizations, and states do not want to jeopardize access to such funding altogether.

However, states may have no qualms about restricting political activities by NGOs because groups engaging in such programming may not be providing crucial services in the first place. Contentious groups may also not be among the NGOs that are receiving official foreign aid. Previous research has documented that donors have incentives to pursue programs that are more regime compatible. These include issues such as good governance, women's representation, and humanitarian aid. However, donors have fewer incentives to pursue programs that are regime challenging.Footnote 119 Thus, states may have no qualms about cracking down on groups pursuing regime-challenging issues such as elections, human rights, media, and corruption, among others.

This dynamic can be seen in Nepal, where 40 percent of state expenditure is financed through official development assistance. Despite numerous recent cases of state crackdown on domestic NGOs in the country, a former employee of a US-based INGO argued that state crackdown on INGOs is muted due to the country's heavy reliance on foreign aid. This has resulted in a scenario where “national-level posturing toward INGOs is always delicately handled.”Footnote 120 On the other hand, the state has more freely repressed domestic NGOs. This was particularly the case for NGOs participating in the 2006 Democracy Movement, or Jana Andolan II, a political agitation against the monarchy. NGOs were so central to this movement that in a survey, 30 percent of the respondents who said that they participated in it claimed they did so because they had been organized by NGOs.Footnote 121 Given the widespread support base commanded by these groups, the state repressed political activities by regime-threatening NGOs, but chose to avoid cracking down on INGOs receiving foreign funds and pursuing regime-compatible issues.

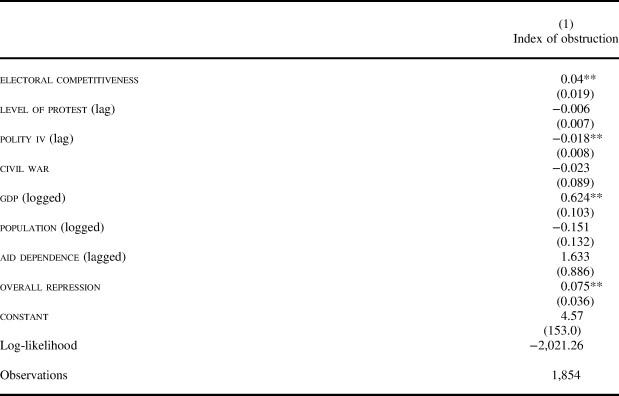

The foregoing analysis focuses on two of the most prominent tactics of administrative crackdown: barriers to foreign funding of NGOs and barriers to political activities by NGOs. I also construct an index of obstruction based on the ten different administrative crackdown variables shown in Table 1.Footnote 122

To test whether the association between electoral competitiveness and states’ use of administrative crackdown still holds when looking at such an index instead of individual laws, I use a negative binomial regression model. Greater electoral competitiveness is positively and significantly associated with more administrative crackdown measures (Table 5). However, the level of protests or mobilization is not significantly associated with administrative crackdown measures in either direction.

Table 5. Crackdown against NGOs, 1990–2013

Notes: Results are based on a negative binomial panel analysis with random effects. Standard errors in parentheses. * p < .10; ** p < .05; *** p < .01.

Finally, given the decision to repress, instead of strategically choosing between different crackdown strategies, states could use both strategies and be outright repressive to silence opponents. To assess this, I create a dichotomous variable both repression that takes a value of 1 if, during a given year, a state is using both a high level of violence and administrative crackdown against NGOs, and 0 if it is not.Footnote 123 In a logistic regression with a random effects specification, factors such as level of democracy, overall repression, or rule of law are not significantly associated with the use of both violent and nonviolent strategies of repression together (Table A5 in the online supplement). States are also neither more nor less likely to use both strategies during increased electoral competition or increased protest levels. Instead, I argue that states using both strategies typically do so because they face multiple kinds of threats from different NGOs all at once. In the next section, I show how the nature of these different threats affects how states use both strategies of repression.

Exploring Alternative Variables to Account for Reporting Bias

Reporting bias may affect the values of variables used in this analysis. The variable on ongoing mobilization (total protests) is based on newspaper reports, which may be less likely to report in smaller or less populated regions, or in regions with greater language barriers. To account for this, I use a variable on anti-system movements from the Varieties of Democracy data set.Footnote 124 This variable captures ongoing threats to the regime, in the form of mobilization, which must have a mass base and an existence separate from normal electoral competition. This ordinal variable ranges from 0 to 4, where 0 denotes that anti-system movements are practically nonexistent, while 4 denotes anti-system movement activity that poses a real and present threat to the regime. Using this variable instead of the total protest variable as a measure of mobilization, I find that the results remain substantively unchanged: as anti-system movements become a bigger threat, states are more likely to violently repress NGOs and activists.Footnote 125

Reporting bias may also affect the dependent variable on violence against NGOs. Given the difficulty of collecting data on violence, these figures are likely to be under-reported because media may focus on certain countries or events rather than others. Smaller events may not even be reported. Therefore, the results given here are likely conservative estimates. In terms of count data, given that Amnesty International is the only source that has maximal worldwide coverage and that it concentrates on attacks on rights defenders as one of its issue areas, it is the best available resource for this kind of data.

However, the Varieties of Democracy data set includes a variable for whether states attempt to repress civil society organizations through violence, among other strategies. This is an ordinal variable ranging from 1 to 5, where 1 denotes that organizations are free to organize, associate, strike, express themselves, and criticize the state without fear of sanctions or harassment and 5 denotes that the state violently and actively pursues all real and even some imagined members of civil society organizations.Footnote 126 Using this variable as a measure of violent attacks on NGOs instead, the results remain substantially unchanged. As the number of total protests in a given year increases, or the threat of mobilization from anti-system movements grows, states are more likely to repress civil society organizations using harassment, arrests, imprisonment, beatings, threats to family, and damage to property.Footnote 127

Variation Across Issue Area and the International–Domestic Dimension: A Case Study

A case study can shed light on why states, once they decide to repress NGOs, employ violence or administrative tools as the means. India has used both strategies and was a pioneer of administrative crackdown starting in the 1970s, a fact that can provide leverage on how states choose among repressive strategies.Footnote 128 The different types of NGOs discussed offer significant variation on my theory's main explanatory variable, the nature of the perceived threat NGOs pose to the state.

India also illustrates how state crackdown strategies differ between domestic and international NGOs. Since the measures used in the quantitative analysis pertain to both kinds, a case study can shed light on how states may perceive the varying levels of threat from them due to the differences in their main target audience. Finally, a historical case spanning several decades also ensures that the outcome is not the result of one particular government or set of elites in power.

For several decades after independence, the Indian government maintained cooperative relationships with a number of domestic and international NGOs that were primarily engaged in rural development and poverty alleviation in the country.Footnote 129 Yet by the 1970s, these relationships had definitively soured. How did these cooperative state–NGO relationships become antagonistic? I demonstrate here how my theory of immediate and long-term threats can shed light on the shifting relationships between the Indian state and various domestic and international NGOs. According to the theory, immediate threats should be more likely to elicit violent crackdowns, while longer-term threats should be more likely to elicit administrative crackdowns. Moreover, there should be evidence that the state chose administrative crackdown to avoid negative consequences associated with violence, especially in targeting INGOs. In what follows, I first shed light on historical periods when NGOs posed long-term versus immediate threats to states, followed by a discussion of how and why state strategies differed between domestic and international NGOs, even when these organizations worked on similar issue areas.

Electoral Influence and Economic Costs: Exploring Long-Term Threats from NGOs

The first major electoral threat to the state from NGOs came during Indira Gandhi's rule in the 1970s. In 1974, Citizens for Democracy succeeded in ousting the government in the state of Bihar. The group then set its sights on the national government in Delhi, campaigning for various electoral reforms as well as the eradication of corruption. This posed a definite electoral threat to the state as the group provided support and training to opposition parties.Footnote 130 At the same time, the Cold War was deepening concerns about external influence in India's domestic electoral politics. This fear was genuine on the part of the state and, as one interviewee put it, “was not merely a smokescreen to enact repressive practices at home.”Footnote 131

To deal with these electoral challenges, in 1976 the Indian state enacted the Foreign Contribution Regulation Act (FCRA). It prohibited donations from foreign states, aid agencies, and foreign corporations, especially to NGOs of a “political” nature. As an interviewee commented, “during the span of the commission's life [1982–87], over 9,000 organizations were accused of subversion, providing perhaps the most dramatic example of tension between a large number of NGOs and the state in India.”Footnote 132 However, with the passage of time and the end of Indira Gandhi's rule in the 1980s, the Indian state lightened its administrative crackdown on NGOs. It further embraced foreign funding with the liberalization of the economy in 1991. An increasing number of NGOs began receiving foreign funding from international sources, including the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund.Footnote 133

However, starting in 2010, the Indian state renewed its discussions on the FCRA and amended the law to make it more stringent. Under the new act, NGOs needed to continually renew their registration and the renewal was subject to state discretion. The act also restricted the proportion of foreign funding that could be used for an organization's administrative expenses, limiting how NGOs could spend their money.Footnote 134 This administrative crackdown was prompted by the increasing electoral and economic threats posed by NGOs. Like numerous other countries where NGO activists have run in elections and threatened the status quo, the incumbent faced challenges with the growth of the Aam Aadmi Party (Common Man's Party). The party grew out of a particular NGO, the Public Cause Research Foundation, and went on to win the 2014 Delhi elections. It did so in part because of its organizational infrastructure, but also by garnering the support of other key NGOs that rapidly broadened the party's base of support.Footnote 135

As my theory would predict, the state consequently renewed its administrative crackdown on NGOs supporting the Aam Aadmi Party. Shortly after, the state also began targeting groups that questioned its development policies. The Modi-led Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government was elected in 2014 on a platform of economic growth. As a policymaker points out, “Given's BJP's proximity to corporates, it is wary of NGOs that fight for people's rights to natural resources.”Footnote 136 One of the main targets of administrative crackdown at this time was the National Alliance of Peoples’ Movements (NAPM). The NAPM scrutinized the activities of multinationals in India and led an anti-nuclear movement.Footnote 137 These activities were perceived as threatening because the state was investing heavily in fossil fuel and nuclear energy. In pushing for renewable energy sources, the NAPM sought to mobilize public opinion against these actions.

Facing such threats, in 2010 the state amended the FCRA to make it even harder for foreign-funded NGOs, including the NAPM, to operate effectively in India. As one official put it, the NAPM was seen as “a dangerous organization, a coalition of all kinds of obstructionists, which tended to obstruct projects related to infrastructure, power, and mining. How can one organization be solely focused on opposing growth-oriented projects? Why do they take no interest in issues such as land reform?”Footnote 138 The threat to the state was clear, resulting in an administrative crackdown.

NGO Mobilization: Exploring Immediate Threats from NGOs

The Indian state's strategy when faced with immediate NGO threats differed from the longer-term threats mentioned earlier. In 1987, a disputed election in Kashmir reignited an insurgency in the region, which lasted for a decade. As a result, the region was increasingly militarized by the Indian state. During this period human rights NGOs monitored widespread human rights violations by state-sponsored paramilitaries, including the shooting of unarmed demonstrators, civilian massacres, and execution of detainees.Footnote 139

The theory predicts that states will use violent crackdown on NGOs engaging in this kind of mobilization. And indeed, many human rights organizations were the victims of state-sanctioned violence during this period. Activists documenting violations in Jammu and Kashmir were attacked, while the state also sanctioned violence against the human rights organizations working in the region of the Naxalite insurgency. On the latter, activists argued that the few NGOs present in this region tried as much as possible to keep a low profile “for fear of drawing attention to themselves” from the state.Footnote 140 Yet some of these activists were threatened with arrest, while others critical of state forces became the targets of state-sanctioned shoot-on-sight orders.Footnote 141

From the Indian government's perspective, the immediacy of the threat during the insurgency warranted a response that could not be realized with administrative crackdown. Violent crackdown was a more timely strategy for disrupting the work of local human rights NGOs. “With such violent crackdown on domestic NGOs, groups were unable to diffuse information about state abuses by contacting international groups,” confirmed one human rights activist. “International NGOs often only approach trusted domestic NGOs, in an effort to maintain credibility. When these sources cannot work, international groups may desist from shaming without credible sources.”Footnote 142 By using violence, the state prevented domestic NGOs from carrying out their programming and ensured that international actors could not access verifiable information to pressure the state.

Variation in State Crackdown Between Domestic and International NGOs

Regardless of the nature of the threat posed by NGOs (immediate or long term), the Indian state always hesitated to use violence against INGOs. According to the theory, INGOs disseminate information better than domestic NGOs. Negative reports by INGOs can reduce trade, aid, and investment in the repressive country. Since INGOs are better able to target international audiences and often have the legal and political backing of their home states, host states may hesitate to use violence against them, preferring more administrative means.

During both the Kashmir and the Naxalite insurgencies, for instance, although human rights INGOs were also the subject of government-sponsored crackdown, it was of the administrative variety. Aryeh Neier, founder of Human Rights Watch, mentioned that India was a major challenge for the organization. Much of the NGO's early reporting on India was focused on Kashmir. The Indian government subsequently declared Human Rights Watch's lead researcher on India persona non grata, and “though India was the country on which she had built her professional career, she could no longer travel there.”Footnote 143 Similarly, beginning in the 1990s, Amnesty International employees were denied visas and more generally obstructed in their dealings with the Indian state. The organization made repeated requests to visit Kashmir for numerous years, but the state refused permission.Footnote 144

Amnesty International later tried to circumvent these administrative obstacles by changing its organizational structure and having Amnesty India registered as a domestic group that was formally separate from its London-based INGO hub.Footnote 145 This organizational change enabled Amnesty India to overcome state-sanctioned barriers to entry against INGOs. Yet the state did not use violence against Amnesty India, unlike other domestic human rights groups. Rather, it continued to obstruct the organization through administrative crackdown. In September 2020, the government froze Amnesty India's bank accounts, forcing the organization to halt its work in the country.Footnote 146 This made India only the second country (after Russia in 2016) where Amnesty International had to entirely cease its operations.Footnote 147 This stringent administrative crackdown can be traced to the fact that Amnesty India pressured the government to investigate civilian deaths in Indian-administered Kashmir, and campaigned against the arbitrary detention of domestic human rights defenders.Footnote 148

India also used administrative crackdown against INGOs posing an economic threat. Greenpeace International was considered threatening to the regime due its public campaign against the coal industry, which was central to the Modi government's plans to boost industrial production. Eventually Greenpeace was accused of engaging in “anti-national” activities, leading to the suspension of its registration and the blocking of its bank accounts.Footnote 149

To understand the logic behind choosing administrative over violent crackdown, I interviewed numerous state officials who were in power when the FCRA was amended in 2010. “States are bigger leviathans now,” one official told me by way of justification for tightening the law. “Such crackdowns are more efficient than killing or threatening factivists individually.”Footnote 150 Even officials from the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (National Volunteer Organization), a voluntary paramilitary organization closely allied with the BJP government—precisely the kind of group one would expect to favor the use of violence over other strategies—articulated their support for using legal means instead of force for “neutralizing” dissidents.Footnote 151

In sum, the case of India shows why and how the state adopted different crackdown strategies when faced with immediate or long-term threats. It also demonstrates how democratic norms do not always preclude state use of repression through legal or administrative means. This is particularly the case when dealing with INGOs, even when these groups may be focusing on similar issues as domestic NGOs.

Conclusion

The international community saw the proliferation of NGOs in the early 1990s as a promising development. It was hoped that these groups could aid service delivery and policy innovation, facilitate free and fair elections, and consolidate democratic gains in countries around the world. With reduced international rivalry, many argued there would be a “symbiotic relationship” between states and NGOs, due to their mutual goals.Footnote 152 However, the data presented in this article show that the increase in the powers of NGOs was alarming to many host states.Footnote 153

This paper examines the conditions under which, given the decision to repress threatening NGOs, states choose to employ violent versus administrative crackdown. I argue that the choice of strategy depends on two main factors: the nature of the threat posed by these groups—particularly whether this threat is immediate or long term—and the consequences of cracking down on them. When states face immediate threats, they are likely to crack down on NGOs with violence. However, this strategy may backfire, as violence reduces the state's legitimacy, violates human rights treaties, increases leaders’ criminal liability, and encourages mobilization against the regime. So states have sought other, less costly ways to crack down on these groups, especially in dealing with threats preventively. States engage in what I term “administrative crackdown,” which enacts legal restrictions to create barriers to entry, funding, and advocacy. Administrative crackdown avoids the negative consequences of violence and is particularly useful in preventing NGOs from influencing electoral activities or outcomes, or threatening a state's economic interests. It is also useful in preventing long-term threats against regimes from coalescing in the first place.

Using original data on violent and administrative crackdown on NGOs from 1990 to 2013, this article shows that ongoing protests are positively and significantly associated with the use of violence against NGOs. On the other hand, when faced with longer-term threats, such as when elections become increasingly competitive and NGOs can influence electoral outcomes, states are, on average, more likely to repress NGOs using administrative crackdown. The data set on multiple strategies of repression of NGOs introduced in this paper could also be used to test other important questions on human rights and transnational advocacy networks, international law, and foreign aid.

Administrative crackdown has important implications for the future of democracy promotion and the use of civil society actors by the international community. The democracy-promotion project was an important part of the vision for a liberal world order, and the crackdown documented here validates its impact, at least in part. States would not be repressing NGOs if these groups were not successful in spreading democratic norms by challenging electoral irregularities, corruption, and a lack of rule of law and respect for human rights.

However, the international context within which the democracy promotion enterprise operates has changed tremendously. Given concerns about democratic backsliding, this article provides a deeper understanding of state–civil society relations, particularly in showing us how even democracies may use autocratic methods to manage nonviolent nonstate actors that challenge their rule.