Food insecurity is the limited or uncertain availability or access to nutritionally adequate, culturally relevant and safe foods(1–Reference Kendall and Kennedy3). It is a dynamic condition and its prevalence may vary by location and time depending on a range of factors(Reference Gundersen and Gruber4–Reference Phillips and Taylor6). Studies undertaken in developed countries over the last 12 years have shown that the prevalence of food insecurity ranges from 4 to 14 % among population-representative samples(Reference Booth and Smith7) and up to 82 % among disadvantaged groups such as ethnic minorities and single-parent families(Reference Kendall and Kennedy3, Reference Booth and Smith7–Reference Chavez, Telleen and Ok12).

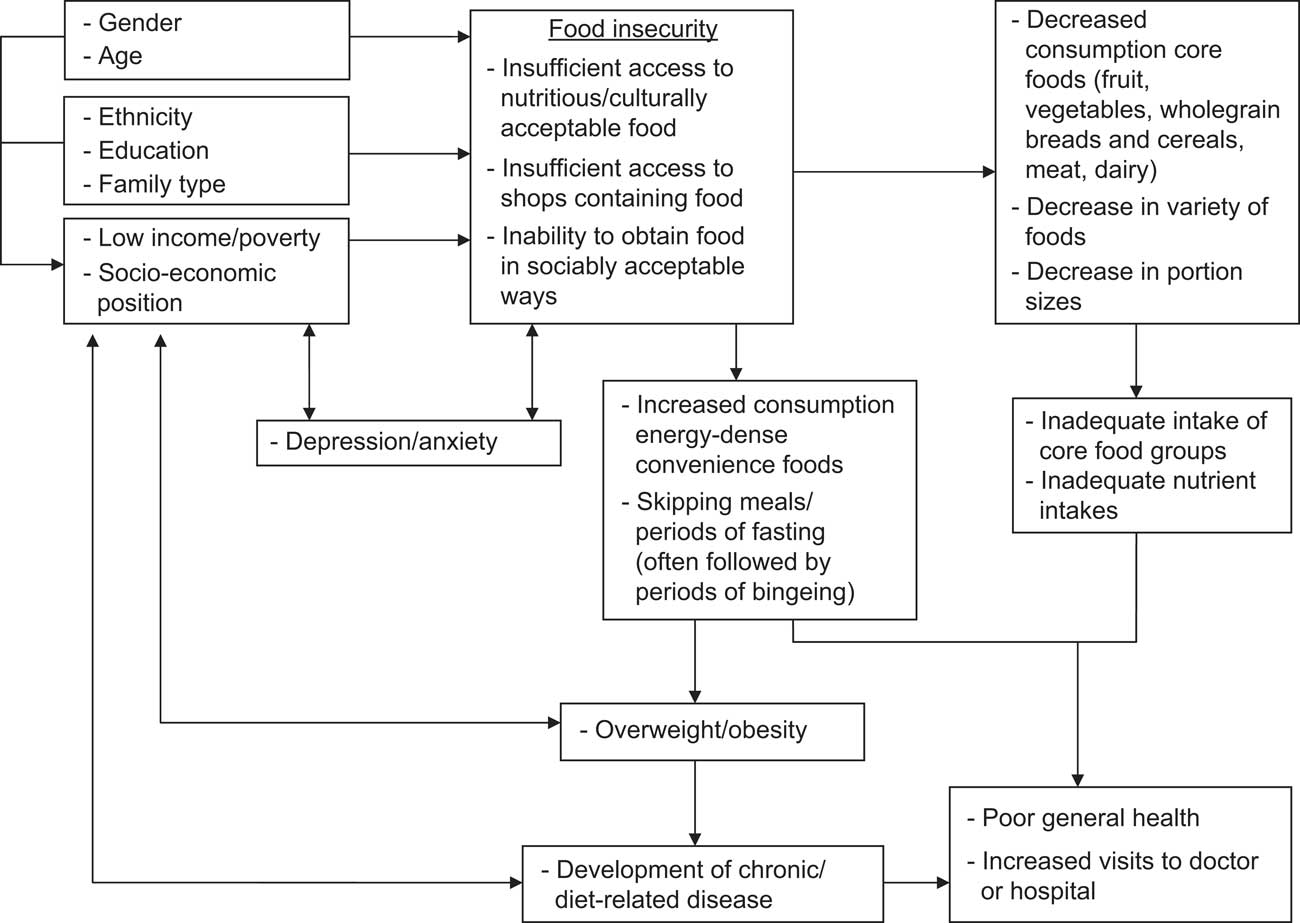

The major predictor of food insecurity is low income or poverty, which limits financial resources for acquiring food(Reference Bartfield and Dunifon10, Reference Stuff, Horton and Bogle13–Reference Cutler-Triggs, Fryer and Miyoshi15). Other potential determinants of food insecurity include belonging to an ethnic minority(Reference Bartfield and Dunifon10, Reference Kaiser, Baumrind and Dumbauld16–Reference Willows, Veugelers and Raine18), having a lower level of education(Reference Bartfield and Dunifon10, Reference Cutler-Triggs, Fryer and Miyoshi15–Reference Kersey, Geppert and Cutts17), being of younger age(Reference Kaiser, Baumrind and Dumbauld16, Reference De Marco and Thornburn19) and family type (single-parent family v. couples with children)(Reference Alaimo, Briefel and Frongillo9, Reference Bartfield and Dunifon10, Reference McIntyre, Connor and Warren14, Reference Vozoris and Tarasuk20). Food insecurity may be associated with lower fruit and vegetable intakes(Reference Radimer, Allsopp and Harvey21–Reference Kaiser, Melgar-Quionez and Townsend25), lower consumption of lean meats(Reference Radimer, Allsopp and Harvey21, Reference Tarasuk23), poorer general health(Reference Stuff, Horton and Bogle13, Reference Vozoris and Tarasuk20, Reference Radimer, Allsopp and Harvey21, Reference Tarasuk23, Reference Siefert, Heflin and Corcoran26–Reference Walker, Holben and Kropf29), chronic conditions such as CVD(Reference Vozoris and Tarasuk20, Reference Weigel, Armijos and Posada Hall30–Reference Holben and Pheley32) and depression(Reference Siefert, Heflin and Corcoran26, Reference Siefert, Heflin and Corcoran27, Reference Laraia, Siega-Riz and Gundersen33–Reference Fuller-Thomson and Nimigon37), and overweight or obesity among women(Reference Wilde and Peterman38–Reference Townsend, Peerson and Love44). There are several hypothesised mechanisms through which food insecurity may be associated with these factors. Budgetary constraints may result in decreased intakes of fruits, vegetables and lean meats, which are perceived to be expensive and less satisfying(Reference Scheier45–Reference Drewnowski and Specter47), and increased intakes of energy-dense foods(Reference Scheier45–Reference Drewnowski and Specter47). These changes may contribute to the development of overweight, obesity or poor health. Food insecurity may also result in a pattern of fasting and bingeing as a consequence of cyclical access to money; this pattern may lead to excess weight gain(Reference Scheier45, Reference Tanumihardo, Anderson and Kaufer-Horwitz48). Corresponding nutrient deficiencies (due to dietary changes), metabolic changes and accompanying stress may, in turn, lead to the development of chronic diseases such as CVD, diabetes or depression, which may result in increased utilisation of health-care services(Reference Wilkinson49). An alternative hypothesis is that poorer general health, depression and chronic disease may result in debilitation, decreased participation in the workforce and, consequently, lower earning capacity or material disadvantage which may contribute to the development of food insecurity. Figure 1 details the hypothesised associations between food insecurity, sociodemographic characteristics, diet, and health outcomes.

Fig. 1 Hypothesised relationships between food security, dietary and health outcomes

Within Australia, screening for food insecurity occurs via a single question in the National Health Survey (NHS), undertaken every three years. Between 1995 and 2004, the rate of food insecurity among the Australian population remained steady at approximately 5 %. Due to the perceived low prevalence of food insecurity, screening was not undertaken in the most recent NHS (2007/08). A comparison of the single-item NHS measure with the more comprehensive US Department of Agriculture Food Security Survey Module (USDA-FSSM) has suggested that the single item may underestimate food insecurity by approximately 5 %. Within Australia specifically, a limited number of studies have investigated the factors associated with food insecurity. Findings suggest that sociodemographic characteristics, including low levels of income, limited financial resources, poor capacity to save money or being unemployed, may be predictors of food insecurity(Reference Radimer, Allsopp and Harvey21, Reference Nolan, Rikard-Bell and Mohsin50–Reference Temple52). Furthermore, living alone or being of single marital status(Reference Radimer, Allsopp and Harvey21, Reference Quine and Morrell51, Reference Temple52), experiencing poor health or disability(Reference Nolan, Rikard-Bell and Mohsin50–Reference Temple52) and renting as opposed to being a home owner(Reference Nolan, Rikard-Bell and Mohsin50, Reference Quine and Morrell51) were factors potentially associated with food insecurity.

Few studies internationally have examined how a broad range of health behaviours and health risk factors are associated with food insecurity and no known Australian studies exist investigating these. The recent financial crisis co-occurred with a food crisis, creating an unprecedented rise in the prevalence of food insecurity internationally through a combination of increasing domestic food prices, decreased income and higher rates of unemployment(53, 54). It is envisaged, therefore, that the health and social burdens of food insecurity may increase worldwide, particularly among socio-economically disadvantaged groups(53, 54).

Despite the increasing global salience of food insecurity, most studies investigating its potential consequences have been conducted in the USA. Most studies outside the USA have primarily utilised crude, one-item indicators of food security which have been shown to underestimate the prevalence of food insecurity, limiting their ability to assess food security status(Reference Nolan, Rikard-Bell and Mohsin50, Reference Keenan, Olson and Hersey55). The range of measures of food insecurity applied outside the USA has further restricted the comparability of the prevalence of food insecurity between countries, limiting our understanding of the implications of food insecurity in other developed nations.

To date, most studies that focused on food insecurity have examined either a population-representative sample or population subgroups at increased risk, such as ethnic minorities or single-parent households. Few studies have examined the prevalence and potential consequences of food insecurity in geographical areas of concentrated socio-economic disadvantage. This is of significance, given that: (i) health promotion strategies and welfare agencies are increasingly servicing defined geographic areas; and (ii) efforts to improve health are increasingly being tailored to areas(Reference Prochaska56, Reference Glanz, Lewis and Rimer57).

The current study addresses these limitations in understanding the sociodemographic, dietary and health factors associated with food insecurity and builds on current food security knowledge as it examines the prevalence, health and health-related behaviours associated with food insecurity among residents of socio-economically disadvantaged urban areas in Australia. It also examines several aspects of health that have previously been investigated in disparate studies.

Methods

The present study was approved by the Queensland University of Technology ethics committee (approval number 0800000735).

Study scope and sampling

The study was conducted in the Brisbane Statistical Sub-Division, Australia. The sampling of individuals was undertaken in a two-stage procedure. The first stage involved the identification of the most disadvantaged 5 % of census collector districts (CCD) in Brisbane, according to each CCD's Index of Relative Socioeconomic Disadvantage (IRSD). The IRSD is derived from the Australian Bureau of Statistics using census variables related to advantage and disadvantage (including income, education and employment). The IRSD reflects a continuum of disadvantage through advantage, with lower values indicative of greater disadvantage(58).

Stage two of the sampling involved selecting 1000 individuals aged between 25 and 45 years from households within these CCD. Individuals between these ages were selected in order to capture the age group with the greatest likelihood of having a residential child (related to a subsequent aim of the study); however, the final age of respondents ranged between 20 and 59 years. Data providing name, gender, age and address were accessed via the electoral roll (voting is compulsory for all adults above 18 years of age in Australia). The electoral roll for the Brisbane Statistical Sub-Division was geocoded to the selected CCD using MapInfo version 11·5 software (MapInfo Corporation, Troy, NY, USA) and households within these CCD were identified. A total of 1000 households were then randomly selected to participate in the study.

Participants and data collection

Data collection occurred between March and May 2009. Individuals were contacted about their participation in the study using the mail-out method developed by Dillman(Reference Dillman59). All selected individuals were offered a small financial gratuity comprising a $AU 1 lottery ticket. The questionnaire was twelve pages in length, comprised primarily of previously validated items, and sought information on dietary and health factors, household food security status and sociodemographic information.

Food security status

Food security was assessed using the USDA-FSSM. This is an eighteen-item food security screening questionnaire with reliability of α = 0·75 in the current sample, and categorises households as: (i) food secure, (ii) low level of food security, (iii) very low level of food security and (iv) very low level of food security among children. As the proportions of households experiencing each individual level of food security were small (11·1 % low level of food security, 12·7 % very low level of food security and 0·8 % very low level of food insecurity among children), this variable was dichotomised as ‘food secure’ or ‘food insecure’.

Sociodemographic characteristics

Data on gender, age, country of birth, equivalised household income, family type and indigenous status were collected. Participants were asked to indicate their gender (‘male’ or ‘female’) and indigenous status (‘non-Indigenous’ or ‘Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander’). To determine country of birth, participants were asked to record the country in which they were born. These were categorised into ‘Oceanic/Antarctica’, ‘Europe’, ‘Africa and the Middle East’, ‘Asia’ and ‘the Americas’. Age was reported as a continuous variable then categorised for analyses. Participants were also asked to report their total gross household income. Equivalised income was then calculated as per the methods employed by the Australian Bureau of Statistics. First, individuals within the household were provided weightings (1 for the first adult, 0·5 for consecutive adults, 0·5 for the first child and 0·3 for each consecutive child). Each weighting was multiplied by the number of corresponding adults or children and then summed(60). The income mid-point for each category was then divided by this number and categorised into tertiles, with the lowest tertile indicating the lowest income per household unit.

Fruit and vegetable intakes

Intakes of fruits and vegetables (including potatoes) were assessed using short answer questions from the Australian NHS(60). Participants were asked ‘How many pieces of fruit do you usually eat per day?’ and ‘How many servings of vegetables do you usually eat per day?’ Responses to this item were categorised as: ‘1 serving per day or less’, ‘2 servings per day’ or ‘3+ servings per day’.

Meat consumption

Questions relating to meat consumption were modified from those used in the Queensland Cancer Risk Study(61). Participants were asked to report on their usual weekly consumption of red meat, fish, chicken and processed meats (such as sausages, salami, etc.; e.g. ‘How many times per week do you eat red meat?’). Responses were categorised as ‘never/less than once per week’, ‘one to two times per week’ or ‘three or more times per week’.

Takeaway consumption

Takeaway consumption was measured using items modified from the 1995 Australian National Nutrition Survey (NNS; the most recent NNS to date)(62). These items measured the frequency of consumption of potato chips, fries or wedges, hamburgers, Chinese food, pizza, cakes, savoury pies, fried fish and fried chicken; these were the ten most popular takeaway items consumed by the Australian population(62). Responses were coded as ‘never/ rarely’, ‘less than once per week’ and ‘one or more times per week’.

Self-assessed health and depression

A single item asked participants to rate their overall health (‘excellent’, ‘very good’, ‘good’, ‘fair’ or ‘poor’). The depression domain from the Short Form 12 (SF12; reliability of α = 0·79 among this sample) was summed to provide a continuous scale which was categorised into tertiles to indicate risk of depression (‘low’, ‘medium’, ‘high’); higher scores indicated higher risk of depression.

Chronic disease

Consistent with the NHS, participants were asked to indicate (‘yes’ or ‘no’) whether they had been told by a doctor, nurse or health professional that they had diabetes, high blood pressure, hardened arteries, high cholesterol or heart attack(60).

Weight status

Weight status was assessed using BMI. As per standard procedure in mail-based surveys, participants were asked to report their height and weight. BMI was calculated and categorised as underweight/normal weight (BMI < 25·00 kg/m2), overweight (BMI = 25·00 to 29·99 kg/m2) and obese (BMI ≥ 30·00 kg/m2) using the WHO international classification for adults’ BMI(63).

Covariates

Based on bivariate analyses, indigenous status, education, household income and family type were associated with food insecurity and were considered to be potential confounding variables (Table 1). Chi-square analyses were undertaken to investigate the associations between these covariates and each of the potential outcomes to be investigated. Covariates that were associated with both food insecurity and the potential outcome at the bivariate level were adjusted for during multivariate analyses. As such, each analysis investigating the association between food insecurity and a specific outcome has uniquely adjusted for all relevant potential confounding variables. The covariates adjusted for during each analysis are summarised in the footnotes of Table 3.

Table 1 Association between food security status and sociodemographic covariates: individuals aged ≥ 20 years (n 487) from disadvantaged suburbs of Brisbane city, Australia, 2009

*Significant at P < 0·05.

Based on previous literature, gender was considered a potential effect modifier and results were initially stratified by gender. However, as there were no differences between results that were stratified for gender and those that were not and the direction of associations between food insecurity and potential outcomes were similar for both males and females, data were combined to provide more statistical power.

Data analyses

Data were analysed using the SPSS statistical software package version 16 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Chi-square analysis was used to test for statistical significance between food security status and the sociodemographic and outcome variables. Binary and multinomial logistic regression analyses were then used to assess the potential determinants and outcomes of food insecurity controlling for the appropriate covariates. For variables with more than 5 % of data missing, a separate category, ‘missing’, was created.

Results

Of the 1000 individuals sampled, three were unable to speak English, forty-nine no longer resided at the address listed on the electoral roll and one was overseas; these groups were therefore unable to complete the questionnaire, leaving 947 potential participants. Five-hundred and five completed questionnaires were returned, resulting in a final response rate of 53 %.

Table 1 summarises the associations between sociodemographic characteristics and food insecurity. At the bivariate level, household income, indigenous status, education and family type were associated with food insecurity. After each of these variables was included in a logistic regression model, equivalised household income was the only factor that remained significant.

Table 2 summarises the demographic and food security characteristics of participants in the study. The sample was comparable to the general population residing in the selected CCD in terms of gender and country of birth. Our sample included a slightly increased proportion of higher-income households than the general population. As we intentionally selected our sample according to age range, our sample differed slightly with regard to age distribution and household structure, with a lower proportion of individuals aged 20–29 years (17 % in the study sample v. 28 % in the general population of the eighty-two CCD) and higher proportions of individuals aged 40–49 years (35 % v. 25 %) and couples with children (49 % v. to 37 %). The prevalence of food insecurity was about 25 %.

Table 2 Demographics and food security characteristics of the study sample (n 487) compared with the total population in the selected census collector districts (CCD), disadvantaged suburbs of Brisbane city, Australia, 2009

The diet and health characteristics and the results adjusted for sociodemographic covariates are summarised in Table 3. Although lower fruit and vegetable intakes were reported by those from food-insecure households, differences were not statistically significant.

Table 3 Diet and health characteristics (%) according to food security status and adjusted associations (odds ratios and 95 % confidence intervals) between health and dietary outcomes and food security status: individuals aged ≥ 20 years (n 487) from disadvantaged suburbs of Brisbane city, Australia, 2009

GP, general practitioner.

*Significant at P < 0·05.

†Adjusted for equivalised household income.

‡Adjusted for indigenous status.

§Adjusted for equivalised household income, indigenous status, household structure and education.

∥Adjusted for family type.

¶Adjusted for equivalised household income and education.

††Adjusted for family type and indigenous status.

‡‡Adjusted for equivalised household income and indigenous status.

§§Adjusted for indigenous status.

∥∥Adjusted for education and family type.

¶¶Adjusted for equivalised household income, indigenous status and household structure.

†††Adjusted for education.

There were no significant associations between food insecurity and meat consumption; however, the findings showed that food-insecure households were two-and-a-half times more likely to report more frequent hamburger consumption. For health outcomes, food insecurity was associated with a two- to threefold increase in having seen a general practitioner and with a twofold higher likelihood of being hospitalised within the last 6 months. A positive association was seen between food insecurity and poorer general health and depression; food insecurity was associated with a threefold increase in experiencing fair or poor general health and with a two- to sixfold increase in likelihood of depression among respondents compared with those who were not food insecure. Weight status was not associated with food insecurity.

Discussion

Our findings showed that food insecurity was prevalent among adults residing in socio-economically disadvantaged areas of urbanised Australia. Food insecurity was associated with lower household income and multiple adverse health behaviours and outcomes, such as increased risk of depression, poorer general health and more frequent hospitalisations or visits to general practitioners. We did not find evidence that food insecurity was associated with other sociodemographic characteristics or with fruit and vegetable intakes, meat consumption, weight status or chronic disease among this sample. These findings suggest that food insecurity is a salient public health issue among residents of socio-economically disadvantaged areas outside the USA. Health promotion and welfare strategies aimed at improving food security status may need to address the increased rates of poor health, depression and health-service utilisation associated with food insecurity to reduce the potential burden of these health and social consequences in such areas.

As expected, lower household income was associated with food insecurity. This is likely due to fewer financial resources with which to acquire food (resulting in food insecurity). At the bivariate level, indigenous status, education and family type were also associated with food insecurity. However, these associations were no longer statistically significant after adjustment for income. This may suggest that these factors affect food security status indirectly through income, rather than directly.

Consistent with previous findings, we found that food insecurity was associated with poorer general health(Reference Stuff, Horton and Bogle13, Reference Vozoris and Tarasuk20, Reference Radimer, Allsopp and Harvey21, Reference Tarasuk23, Reference Siefert, Heflin and Corcoran26–Reference Walker, Holben and Kropf29), increased risk of depression(Reference Siefert, Heflin and Corcoran26, Reference Siefert, Heflin and Corcoran27, Reference Laraia, Siega-Riz and Gundersen33–Reference Fuller-Thomson and Nimigon37) and more frequent hospitalisations and visits to general practitioners(Reference Kushel, Gupta and Gee64, Reference Nelson, Cunningham and Anderson65). There are two hypothesised pathways by which food insecurity may be associated with adverse health, including (i) physiological and psychological changes due to nutrient deficiencies and (ii) the stress and anxiety experienced as a result of being unable to access sufficient amounts of food. Alternatively depression and poor health may limit participation in the workforce, lowering earning capacity and contributing to the development of food insecurity(Reference Vozoris and Tarasuk20, Reference Siefert, Heflin and Corcoran27, Reference Laraia, Siega-Riz and Gundersen33, Reference Heflin, Siefert and Williams35). The direction of these associations is unclear; to date, studies examining these issues have been cross-sectional, with the exception of two(Reference Siefert, Heflin and Corcoran27, Reference Heflin, Siefert and Williams35) that suggested that food insecurity may be a precursor to depression.

We did not find an association between food insecurity, fruit and vegetable and meat intakes among our sample. Those from food-insecure households reported more frequent consumption of hamburgers, but not other takeaway foods. Evidence from the USA and Canada suggests that food insecurity is associated with lower intakes of fruit and vegetables(Reference Tingay, Tan and Tan22, Reference Tarasuk23, Reference Kaiser, Melgar-Quionez and Townsend25) and lean meat(Reference Tarasuk23). Only one other study has investigated the association between food insecurity and takeaway consumption(Reference Tingay, Tan and Tan22). Similar to the current study, it found no association between food insecurity and consumption of takeaway items(Reference Tingay, Tan and Tan22). Limited consumption or exclusion of lean meats, fruits and vegetables among food-insecure individuals may be due to the perception that these food groups are expensive(Reference Scheier45, Reference Tanumihardo, Anderson and Kaufer-Horwitz48). Objective data collected on food prices suggest that these food groups, which are less energy-dense, are more expensive than satiating energy-dense foods, such as those high in sugars or fats(Reference Drewnowski46, Reference Drewnowski and Specter47). Consequently, food-insecure households may be less likely to consume foods such as lean meats, fruits and vegetables, and more likely to have diets that comprise more energy-dense options(Reference Scheier45, Reference Tanumihardo, Anderson and Kaufer-Horwitz48).

Among the general Australian population, fruit and vegetable intakes have been found to be low, with about 50 % and 10 % of Australian adults consuming the recommended servings of fruits and vegetables, respectively(66). Lower socio-economic groups are less likely to consume the recommended servings of fruits and vegetables(Reference Giskes, Turrell and Patterson67). Our sample of adults comprised primarily participants who were disadvantaged in terms of their area- and individual-level socio-economic position. Compared with a population-representative sample, the fruit and vegetable intakes of the current sample were lower(66). Therefore, an association between food insecurity and fruit and vegetable intakes may not have been apparent, as has been shown in studies utilising samples with greater socio-economic variation(Reference Radimer, Allsopp and Harvey21, Reference Tingay, Tan and Tan22, Reference Kirkpatrick and Tarasuk24).

The findings of the current study did not support an association between food insecurity and weight status. Evidence from previous studies is inconsistent and the existence of an association between food insecurity and weight status remains debatable; some studies have shown a positive association (more consistently seen among women)(Reference Radimer, Allsopp and Harvey21, Reference Wilde and Peterman38–Reference Townsend, Peerson and Love44), whereas others report no association(Reference Weigel, Armijos and Posada Hall30, Reference Jones and Frongillo68–Reference Whitaker and Sarin71). Socio-economic disadvantage, particularly among women, has been shown to be associated with overweight and obesity(Reference McLaren72). The null association found in the current study may be due to the sample being drawn from socio-economically disadvantaged areas. Our reliance on self-reported height and weight to calculate BMI may also explain the lack of an association, as individuals are more likely to overestimate their height and underestimate their weight(Reference Nyholm, Gullberg and Merlo73–Reference Stewart, Jackson and Ford76), resulting in a lower calculated BMI.

We did not find any association between food insecurity and self-reported diabetes, high cholesterol, hardened arteries or stroke. Similarly, this lack of association may be due to our socio-economically disadvantaged sample. There is a limited body of literature pertaining to associations between food insecurity and chronic disease, specifically heart disease, blood pressure, cholesterol and diabetes. Heart disease and high blood pressure have previously been shown to be associated with food insecurity in one Canadian study(Reference Vozoris and Tarasuk20); however, these results were not replicated among other studies in the USA(Reference Weigel, Armijos and Posada Hall30, Reference Holben and Pheley32). Multiple studies have suggested that food insecurity is positively associated with diabetes(Reference Holben8, Reference Vozoris and Tarasuk20, Reference Seligman, Bindman and Vittinghoff43). The evidence pertaining to cholesterol is inconsistent. One study found that food insecurity was associated with raised levels of LDL cholesterol and TAG among American women(Reference Tayie and Zizza31); however, two other studies contradicted these findings(Reference Weigel, Armijos and Posada Hall30, Reference Holben and Pheley32).

The findings of the current study should be interpreted within the context of a number of limitations. First, the cross-sectional nature of the study did not allow for assessment of the temporal relationship between food insecurity and potential outcomes; consequently it is unknown whether food insecurity preceded the development of poor health, depression and increased health-service utilisation or whether food insecurity occurred as a result of these conditions. Second, our data were collected via mail survey, which may have biased the sample against those from non-English speaking backgrounds and/or with poor literacy. Consequently, our study may under-represent some of the most disadvantaged segments of society and those at highest risk of experiencing food insecurity; therefore the magnitude of associations in the current study may underestimate those in the population. Third, our survey relied on self-reported data, leaving our study open to potential response bias. In particular, participants may have under-reported with regard to weight status(Reference Nyholm, Gullberg and Merlo73–Reference Stewart, Jackson and Ford76). Potential under-reporting of food insecurity may suggest a rate higher than the 25 % identified in our study.

There are very few studies investigating the associations between food insecurity, health status, health-care utilisation, chronic conditions and dietary behaviours. More research is required, particularly among developed countries outside the USA, to monitor the prevalence and potential consequences of food insecurity. The findings of the current study may provide a framework for the development or improvement of policies and interventions to address factors associated with food insecurity in an effort to reduce the potential social and economic burdens.

Conclusions

Food insecurity may be prevalent in urbanised disadvantaged areas in Australia; among this sample, approximately 25 % of respondents reported household food insecurity. Households with lower incomes may be at higher risk of experiencing food insecurity. Furthermore, individuals experiencing food insecurity may be at risk of a wide range of adverse health outcomes, including poorer general health and increased risk of depression, and are likely to increase their utilisation of general practitioner and hospital services. As the prevalence of food insecurity is predicted to increase in the context of the recent food and financial crises, the public health significance of food insecurity is likely to increase.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Queensland University of Technology Research Grants Scheme. R.R. was supported by an Australian Postgraduate Award Scholarship and G.T. was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Research Fellowship. There were no conflicts of interest. R.R. conceptualised and wrote the paper, and has primary responsibility for the final content. K.G., G.T. and D.G. assisted in conceptualisation of the review, provided input into writing of the manuscript and feedback on subsequent drafts. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.