Introduction

The quality of early parent-child interactions has consistently been shown to be important for the child’s socioemotional and cognitive development (e.g., Cui et al., Reference Cui, Mistur, Wei, Lansford, Putnick and Bornstein2018; De Wolff & van IJzendoorn, Reference De Wolff and van IJzendoorn1997; Deans, Reference Deans2018; Leerkes et al., Reference Leerkes, Blankson and O’Brien2009; Lucassen et al., Reference Lucassen, Tharner, Van IJzendoorn, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Volling, Verhulst, Lambregtse-Van den Berg and Tiemeier2011) and particularly for infant-parent attachment. Attachment relationships function as a blueprint for future social relationships (Bowlby, Reference Bowlby1969; Thompson, Reference Thompson, Cassidy and Shaver2016) and constitute the framework in which children develop their capacity to regulate emotional distress (e.g., Mikulincer & Shaver, Reference Mikulincer, Shaver, Cassidy and Shaver2016; Thompson, Reference Thompson and Lamb2015). Therefore, the quality of a child’s interactions and relationships with their primary caregivers has long-term implications for the child’s development and well-being (Fearon et al., Reference Fearon, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Van IJzendoorn, Lapsley and Roisman2010; Groh et al., Reference Groh, Roisman, van IJzendoorn, Bakermans-Kranenburg and Fearon2012, Reference Groh, Fearon, Bakermans-Kranenburg, van IJzendoorn, Steele and Roisman2014). While parental psychopathology increases the risk of poor parent-child interaction quality and insecure parent-child attachment (Bernard et al., Reference Bernard, Nissim, Vaccaro, Harris and Lindhiem2018; Madigan et al., Reference Madigan, Fearon, van IJzendoorn, Duschinsky, Schuengel, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Ly, Cooke, Deneault, Oosterman and Verhage2023), it is also linked with early infant social withdrawal (Braarud et al., Reference Braarud, Slinning, Moe, Smith, Vannebo, Guedeney and Heimann2013; Smith-Nielsen et al., Reference Smith-Nielsen, Lange, Wendelboe, Wowern and Væver2019; Stuart et al., Reference Stuart, Stougård, Smith-Nielsen, Egmose, Guedeney and Væver2022). Infant social withdrawal is found to be an early nonspecific risk factor for a range of developmental outcomes, such as behavioral problems, delayed language development, and attachment disorders (Guedeney et al., Reference Guedeney, Matthey and Puura2013; Milne et al., Reference Milne, Greenway, Guedeney and Larroque2009; Smith-Nielsen et al., Reference Smith-Nielsen, Lange, Wendelboe, Wowern and Væver2019). Such evidence has led to a growing interest in developing attachment-based intervention programs targeting at-risk families to promote sensitive parenting and secure child-caregiver attachment relationships (Berlin et al., Reference Berlin, Zeanah, Lieberman, Cassidy and Shaver2016). The present study evaluates the efficacy of the attachment-theory informed intervention, the Circle of Security-Parenting program (COSP™; Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Hoffman and Powell2009) in families with an infant aged 2–12 months where the mother fulfills criteria for postpartum depression (PPD) and/or the infant is assessed to be socially withdrawn.

Extensive research has shown that secure child-caregiver attachment promotes resilience and predicts positive outcomes such as social competence and confidence in the child (Tharner, Luijk, van IJzendoorn, et al., Reference Tharner, Luijk, van IJzendoorn, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Jaddoe, Hofman, Verhulst and Tiemeier2012; Thompson, Reference Thompson, Cassidy and Shaver2016). For a securely attached child, the caregiver acts as a secure base for exploration when the child is not distressed, and when the attachment system is activated (e.g., the child needs proximity and protection because they are frightened), the caregiver provides a safe haven for the child to return to for comfort and emotion regulation. On the other hand, when the caregiver is not able to act as a secure base and/or safe haven, it increases the risk of child insecure or disorganized attachment, which are known risk factors for later emotional and behavioral problems (Fearon et al., Reference Fearon, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Van IJzendoorn, Lapsley and Roisman2010; Groh et al., Reference Groh, Roisman, van IJzendoorn, Bakermans-Kranenburg and Fearon2012). Thus, it is important to consider how to promote secure child-caregiver attachment relationships from infancy, particularly in at-risk families.

Parental sensitivity, i.e., the parent’s ability to notice, interpret, and respond timely and appropriately to the child’s signals (Ainsworth et al., Reference Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters and Wall1978b), is assumed to be the most important predictor of the quality of the attachment relationship the child develops to its parent (Ainsworth, Reference Ainsworth, Caldwell and Ricciuti1973; Fearon & Belsky, Reference Fearon and Belsky2018). If the parent is sensitive to the child’s signals, the child develops the expectation that the caregiver is available to support their needs (Bowlby, Reference Bowlby1969; Bretherton & Munholland, Reference Bretherton, Munholland, Cassidy and Shaver2008). Accordingly, empirical links between parental sensitivity and child-parent attachment quality are well-established (for meta-analyses see, De Wolff & van IJzendoorn, Reference De Wolff and van IJzendoorn1997; Lucassen et al., Reference Lucassen, Tharner, Van IJzendoorn, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Volling, Verhulst, Lambregtse-Van den Berg and Tiemeier2011; Zeegers et al., Reference Zeegers, Colonnesi, Stams and Meins2017). However, parental sensitivity also only partly explains individual differences in attachment quality. In a meta-analysis, Zeegers and colleagues (Reference Zeegers, Colonnesi, Stams and Meins2017) pointed to parental reflective functioning, or parental mentalizing, as an important predictor of child-caregiver attachment quality. Parental reflective functioning is defined as the parent’s ability to reflect upon the ongoing psychological processes in their child and in themselves as a parent (Fonagy et al., Reference Fonagy, Steele, Steele, Moran and Higgitt1991; Slade, Reference Slade2005) and allows the parent to “decode” child behavior, linking it to mental states, and thereby provides the parent with a greater understanding of the child’s needs (Fonagy & Allison, Reference Fonagy, Allison, Midgley and Vrouva2013). While neither parental sensitivity nor mentalizing can predict all of the variance in child-parent attachment quality, they can nonetheless be considered important in early parent-child relationships.

One factor that has been found to impact the parent-child relationship negatively is depression in the postpartum period. PPD is common among postpartum women, affecting 12–17% of healthy mothers (Shorey et al., Reference Shorey, Chee, Ng, Chan, Tam and Chong2018; Woody et al., Reference Woody, Ferrari, Siskind, Whiteford and Harris2017). Compared to non-depressed mothers, mothers with depression are at increased risk of being less engaged with their children, more irritable, and to exhibit fewer emotions and less warmth (Feldman et al., Reference Feldman, Granat, Pariente, Kanety, Kuint and Gilboa-Schechtman2009; Feldman & Eidelman, Reference Feldman and Eidelman2007; Neri et al., Reference Neri, Agostini, Salvatori, Biasini and Monti2015). Further, research indicates that these early disruptions in mother-infant interaction may cause infant social withdrawal and negative affect in social interactions (Guedeney et al., Reference Guedeney, Matthey and Puura2013; Smith-Nielsen et al., Reference Smith-Nielsen, Lange, Wendelboe, Wowern and Væver2019; Tronick & Reck, Reference Tronick and Reck2009). Meta-analytic evidence shows that PPD is linked with compromised sensitivity (Bernard et al., Reference Bernard, Nissim, Vaccaro, Harris and Lindhiem2018) and decreased mentalizing abilities (Georg et al., Reference Georg, Meyerhöfer, Taubner and Volkert2023). Further, in a review, Śliwerski et al. (Reference Śliwerski, Kossakowska, Jarecka, Świtalska and Bielawska-Batorowicz2020) found that PPD may impact the emerging attachment relationship, however, only in the first six months postpartum, and a recent meta-analysis by Madigan and colleagues (Reference Madigan, Fearon, van IJzendoorn, Duschinsky, Schuengel, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Ly, Cooke, Deneault, Oosterman and Verhage2023) found that disorganized attachment was more likely if the parents had some form of psychopathology, including depression.

Due to the importance of parental caregiving behavior for later child development, several interventions, which are intended to positively impact child development, aim at increasing sensitive maternal behavior and secure child-caregiver attachment relationships (for reviews, see Berlin et al., Reference Berlin, Zeanah, Lieberman, Cassidy and Shaver2016; Mountain et al., Reference Mountain, Cahill and Thorpe2017; Steele & Steele, Reference Steele and Steele2018). One such program is the COSP™ (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Hoffman and Powell2009). The COSP™ program is a manualized group-based intervention that aims to promote the development of child-caregiver secure attachment relationships, utilizing insights from the attachment literature (Powell et al., Reference Powell, Cooper, Hoffman, Marvin and Zeanah2009). As a briefer version of the COS-Intensive group therapy model (Hoffman et al., Reference Hoffman, Marvin, Cooper and Powell2006; Woodhouse et al., Reference Woodhouse, Powell, Cooper, Hoffman, Cassidy, Steele and Steele2018), COSP™ is designed to be accessible to a wide range of parents, from high to low risk, with children up to six years old (Cassidy et al., Reference Cassidy, Brett, Gross, Stern, Martin, Mohr and Woodhouse2017). While the program uses pre-produced video vignettes to demonstrate typical parenting challenges in meeting children’s attachment needs, it also involves the parents’ bringing in examples of their own experiences, thereby combining educational and therapeutic elements (Marvin et al., Reference Marvin, Cooper, Hoffman and Powell2002).

The assumption of COSP™ is that facilitating caregivers’ understanding and reflections on children’s attachment needs, leads to increased parental sensitivity, hereby fostering the development of secure child-parent attachment (Woodhouse et al., Reference Woodhouse, Powell, Cooper, Hoffman, Cassidy, Steele and Steele2018).

Central to the COSP™ program are the concepts of safe haven and secure base as defined by Bowlby and Ainsworth. These concepts are key in the complex and dynamic interplay between the two innate behavioral systems of attachment and exploration interacting in an interdependent and circular way. When the infant is distressed, i.e., the attachment system is activated, the infant seeks proximity and the caregiver acts as the “safe haven”. When the fear system is reactivated, the caregiver acts as the “secure base” from which the infants explore the world and learn (e.g., Grossmann & Grossmann, Reference Grossmann and Grossmann2020). Children develop secure attachment relationships to their caregivers when caregivers provide both a “safe haven” for comfort and affect regulation and a “secure base” for exploration support. These concepts serve as a tool for the caregivers to reflect on their relationships with their children, aiming to foster positive parent-child interactions. The group sessions are led by a certified COSP™ facilitator, who guides caregivers in applying this framework to both the video vignettes, their examples of real-life interactions with their children, and the parents’ own childhood experiences with having a safe haven and secure base. This process of joint reflection with a facilitator, particularly on obstacles to meeting a child’s needs, is seen as the intervention’s mechanism of change, leading to increased mentalizing skills and more empathetic, responsive, and attuned parenting, which in turn is hypothesized to facilitate secure parent-child attachment.

Since the current study was designed and initiated in 2015, a number of studies evaluating the COSP™ have been published. These studies have found mixed results regarding parenting and child outcomes (see Zimmer-Gembeck et al. (Reference Zimmer-Gembeck, Rudolph, Edwards, Swan, Campbell, Hawes and Webb2022) for an overview). To the best of our knowledge, only four previous RCTs of COSP™ exist. Cassidy and colleagues (2017) investigated the efficacy of COSP™ in a randomized wait-list control study with 141 low-income mothers (75 in the intervention group) and their 3–5-year-old children. They found no effects of the COSP™ on child-caregiver attachment classifications, maternal supportive responses to her child’s distress, or child internalizing or externalizing behavior. However, they did find significantly fewer unsupportive maternal responses to child’s distress in the COSP™ group compared to the control group, as well as increased child inhibitory control. In exploratory post-hoc analyses, they found that maternal avoidant attachment moderated the effect of COSP™ on child-caregiver attachment quality. The moderation showed that when the mothers were more avoidant in their self-reported attachment style, the COSP™ children were both significantly more secure and less disorganized. Cassidy et al. (Reference Cassidy, Brett, Gross, Stern, Martin, Mohr and Woodhouse2017) argued that this moderator-effect highlights the fact that only subgroups benefit from COSP™ in its standardized form which may also contribute to their many non-significant results. They further suggest that future research should investigate how to further tailor the COSP™ sessions to suit the individual’s parenting needs. Risholm Mothander et al. (Reference Risholm Mothander, Furmark and Neander2018) compared the effect of COSP™ + care-as-usual (CAU) versus CAU only in 52 clinical mothers (28 in each group) and their 0–4-year-old children. They found no significant differences between the treatment groups on neither the mothers’ internal representations of their parenting or the relationship with their infant nor on mother-infant interaction quality. Risholm Mothander and colleagues (Reference Main, Solomon, Greenberg, Cicchetti and Cummings2018) interpret their lack of significant findings due to the high quality in CAU, meaning that they would not see any effects when adding on COSP™ to already comprehensive interventions. Zimmer-Gembeck et al. (Reference Zimmer-Gembeck, Rudolph, Edwards, Swan, Campbell, Hawes and Webb2022) compared 51 parents receiving COSP™ with 34 parents on a waitlist all of whom were at-risk of parenting distress/problems and child disruptive behavior. The children were 1–7 years old. They found that only self-reported parental attachment anxiety was significantly decreased in the COSP™ group, with no significant group differences on child behavior, parenting practices, parenting stress, depression, or reflective functioning. Zimmer-Gembeck et al. (Reference Zimmer-Gembeck, Rudolph, Edwards, Swan, Campbell, Hawes and Webb2022) suggested that the psychoeducational aspect of COSP™ was not effective in itself and that the intervention could perhaps be improved by adding on modules with direct individual feedback on parenting. Finally, Røhder et al. (Reference Røhder, Aarestrup, Væver, Jacobsen and Schiøtz2022) investigated an adapted version of COSP™ to pregnant women with psychosocial vulnerabilities. In this adapted version, two sessions occurred pre-birth, and the remaining seven modules occurred when the infant was between 9–36 weeks old. They compared 40 mothers in the COSP™-group with 38 mothers receiving CAU (i.e., extra ultrasounds examinations and consultations with general practitioners and midwives). They found no significant differences between the two groups on maternal sensitivity, reflective functioning, well-being, or the infant’s socioemotional functioning. However, they did find that COSP™ significantly reduced parental stress. Røhder et al. (Reference Røhder, Aarestrup, Væver, Jacobsen and Schiøtz2022) argued that their lack of significant findings may be because the CAU included extra care and support where they may also focus on supporting and improving mother-infant interaction quality. Thus, in summary, previous RCTs of COSP™ have not found main effects of the intervention on interaction quality, reflective functioning, or child-caregiver attachment quality in at-risk families. However, Cassidy et al. (Reference Cassidy, Brett, Gross, Stern, Martin, Mohr and Woodhouse2017) did find a moderated treatment effect on child-caregiver attachment quality. While there has been mixed results of the effect of COSP™, many municipality health visitors in Denmark are currently now trained/being trained in the program (Hammershøj, Reference Hammershøj2023), and we thus wanted to evaluate the effect of the program in a Danish setting.

Based on the theoretical model of change in COSP™ and the program’s core aims (i.e., increasing sensitivity and secure child-caregiver attachment), the current RCT aimed to evaluate the effect of COSP™ when delivered as a group-based preventive 10-session program compared to Care as Usual (CAU) in a Danish sample of mothers of infants aged 2–12 months where the mother had PPD and/or the infant showed social withdrawal. Our hypotheses were: The COSP™ intervention leads to (1) improved maternal sensitivity, (2) improved maternal reflective functioning, and (3) more securely attached children compared to CAU. We also investigated whether risk condition (maternal PPD and/or infant social withdrawal) and disadvantaged family status (i.e., low socioeconomic status) moderates the treatment effect on the three outcomes.

Methods

Participants

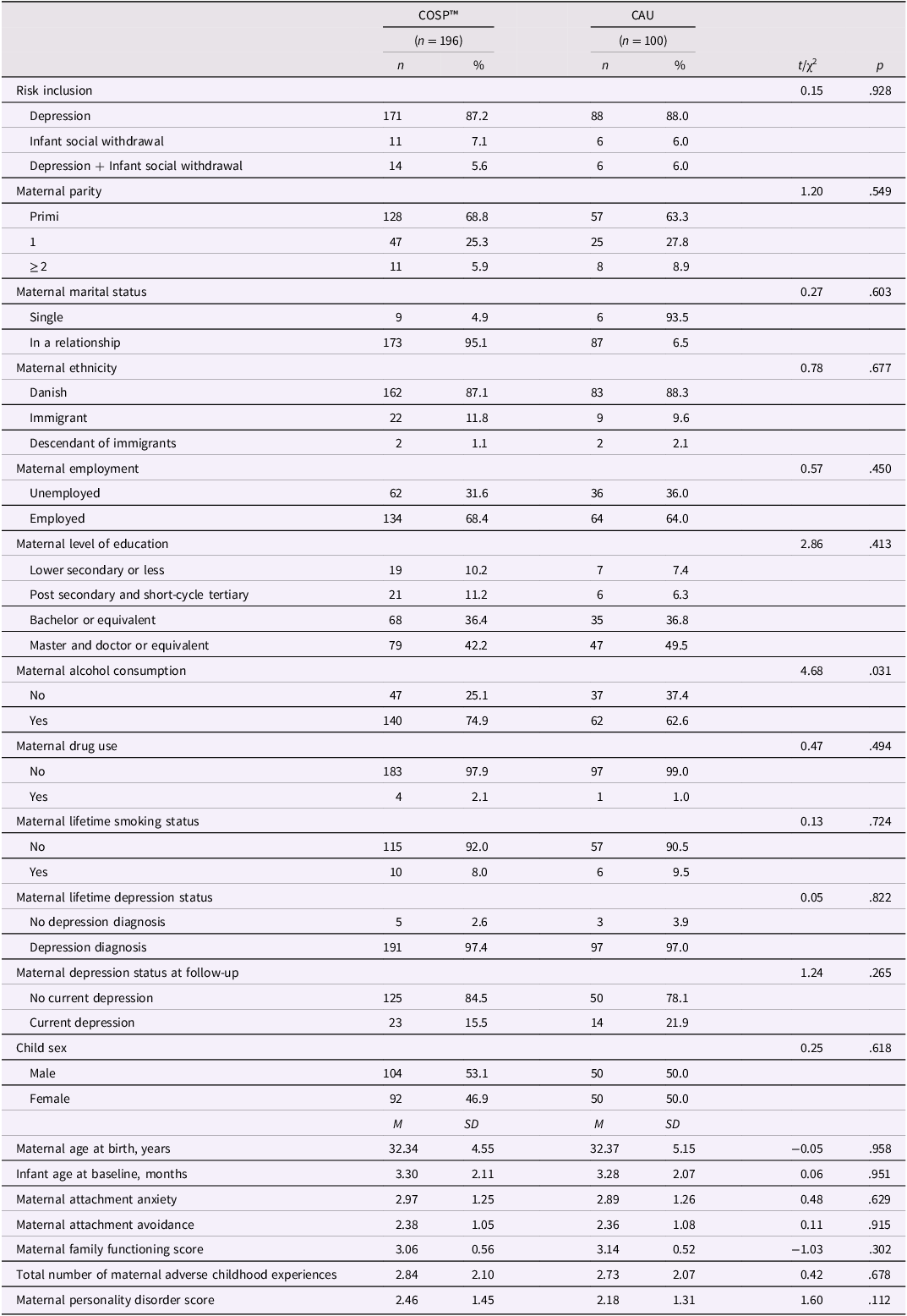

This RCT study was preregistered in the protocol paper for the Copenhagen Infant Mental Health Project (CIMHP; Væver et al., Reference Væver, Smith-Nielsen and Lange2016) and was approved by the local ethical review board (Approval number: 2015-10). It was conducted in collaboration with the municipal health visitors in Copenhagen, and inclusion ran from 2015–2019. In all, 297 mothers and their infants were included in the study. Table 1 shows the sample characteristics for the RCT study. The majority (87.5%) were included based on the PPD screenings. While this was an at-risk sample, mothers were generally well-functioning in that the majority had completed a higher level of education (77.3%), lived with a partner (87.8%), and were employed when not on maternity leave (66.9%). As we can see from Table 1, the randomization was not successful regarding maternal alcohol consumption (self-report about consumption within the last month prior to the time of baseline assessment, i.e., postpartum), with more mothers consuming alcohol in the intervention group. However, the effect size (φ = .128) indicated that this was a small difference between the two groups, and it may just be a type I error due to multiple testing. Nonetheless, it is important to keep in mind that this potential difference is of significance.

Table 1. Sample characteristics

Procedure

As part of the national, universal health care services in Denmark, all families are offered routine visits by public health visitors during the first year postpartum. In Copenhagen, the families are visited right after birth and when the infant is around two months, four months (this visit is only offered to first time parents), and 8 months old. During these visits, the health visitor screens the mother for PPD using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS; Cox et al., Reference Cox, Holden and Sagovsky1987) and the infant for social withdrawal using the Alarm Distress Baby Scale (ADBB; Guedeney & Fermanian, Reference Guedeney and Fermanian2001). If the mother scored 10 or above on the EPDS and/or the infant scored 5 or above on the ADBB, the family was invited to participate in CIMHP. Inclusion criteria further encompassed that the mother was ≥18 years old, spoke and understood Danish, and the mother fulfilled criteria for a depression diagnosis according to DSM-5 (First et al., Reference First, Williams, Karg and Spitzer2015) AND/OR the infant scored 5 or above on a second ADBB assessment conducted within a range of 10–20 days after the first one. Exclusion criteria were that the infant had a severe medical condition/early retardation, extremely premature birth (< 28 weeks), maternal bipolar/psychotic disorder, known severe intellectual impairment, mother attempted suicide pre- or postpartum, mother shows alcohol/substance abuse, and if the families expressed that they would move away from Copenhagen during the RCT study period. Further, children were not included in the study if they were younger than two months or older than 10 months. This was due to the ADBB only being valid to use in infants from the age of two months, and because the infant needed to not be older than 10 months to provide sufficient time for the family to undergo baseline assessment, enter the RCT, and participate in follow-up assessments.

After referral, a psychologist from the research team visited the family in their home where they obtained written and informed consent from the mother and, in cases of shared custody of the child, from the partner in approval of the infant’s participation. This visit functioned as the baseline measurement point. The psychologist conducted interviews with the mother - including a diagnostic interview to assess maternal depression - and a five-minute free-play mother-infant interaction was video-recorded. Questionnaires were also sent online at the time of the home visit for the mother to fill out.

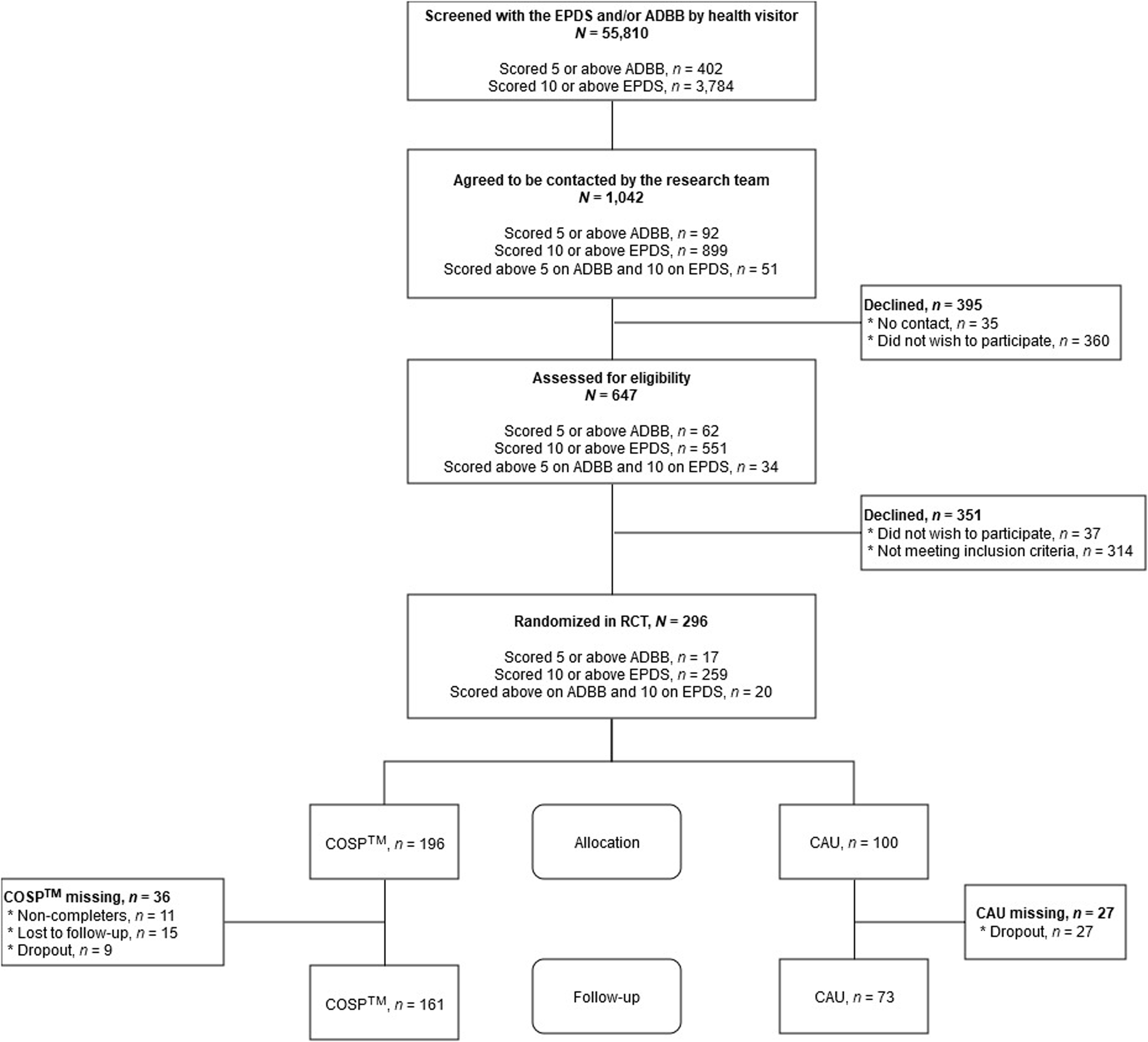

The family was randomly allocated 2:1 to the COSP™ intervention+CAU or CAU. The 2:1 randomization to COSP™ was conducted to include participants and thereby minimize waiting time for the groups to be filled. The families in the COSP™ intervention also received CAU. The COSP™ program was delivered over 10 sessions, corresponding to 10 weeks. Follow-up assessments could take place when the infant was at least 11 months old and maximum 16 months old due to the age restrictions on the assessment of child-mother attachment quality. The timing of follow-up assessments was guided by the infant’s age at baseline and the goal of ensuring consistency in the time between enrollment and follow-up. Families were contacted for follow-up approximately one month before the infant’s optimal age for assessment, which was typically 12 months but could range between 12 and 15 months depending on the infant’s age at baseline (see supplementary materials, Table S1, for an overview of the approach). This approach ensured attachment was assessed at a developmentally appropriate time while maintaining consistency across participants. Thus, some families who entered the RCT with very young infants waited longer for the follow-up assessment. On average the waiting time was 223.89 days (SD = 71.37 days, range: 31–389 days), i.e. 7.4 months. The follow-up assessments took place at the university laboratory. Here, maternal depression was examined using the diagnostic interview, free-play mother-child interactions were video-recorded, and the Strange Situation Procedure (SSP; Ainsworth et al., Reference Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters and Wall1978a) was conducted. Online questionnaires were also sent out to mothers at the time of the follow-up visit. Figure 1 shows the flowchart of the procedure.

Figure 1. Flowchart of participants.

Care as usual (CAU) intervention

The CAU intervention was standard practice for mothers with PPD. At minimum, CAU included that the families receive the standard home visits from the health visitor. CAU could include additional home visits or phone calls from health visitors, individual counseling sessions, group therapy (e.g., PPD or parenting groups) provided by family therapists or psychologists, and/or pharmacological treatment. Table 2 shows the frequencies of the additional treatments apart from the standard home visits in the two intervention groups. A bit over half of the participants in the COSP™ also received some form of additional CAU, with the majority receiving individual therapy. In the CAU group, the majority received either individual or individual and group therapy. There was no significant difference between the two groups and whether they received any psychotropic drugs for their PPD.

Table 2. Overview of care as usual (CAU)

Circle of security-parenting (COSP™) intervention

The COSP™ is a manualized parenting program designed to be delivered in groups for parents of children aged 0–6 years. During the intervention, parents view pre-produced video vignettes of parents and their children in different contexts and are invited to engage in discussions about parent-child interactions. Parents are encouraged to share “circle stories” in every session, detailing their own children’s ways of expressing needs for exploration, closeness, and emotional regulation, and how they as parents are able to meet or may struggle with accommodating these needs. These personal narratives are instrumental for facilitators in guiding parents to understand how to support the development of a secure child-caregiver attachment relationship. The COSP™ manual outlines the facilitator’s role in directing discussions towards particular themes using the video vignettes from each chapter. In this study, we used the Danish COSP™ manual (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Hoffman and Powell2009), which was translated with small cultural adaptations into the Danish language by native Danish speakers in collaboration with the original authors. The COSP™ material used in the RCT is produced in the US and shows English speaking parents and their children. There was, however, a Danish speaking narrator on the videos, Danish subtitles on parent-child interactions, and all parenting resources, such as exercises and handouts, were also in Danish. The intervention was delivered over 10 weekly sessions, each 90 minutes long. Each group, consisting of 6–10 parents, was co-facilitated by a pair of certified Circle of Security-Parenting (COSP™) facilitators with minimum one of the facilitators being a psychologist. In total, nine facilitators collaboratively conducted 36 COSP™ groups. The sessions were held in a room at the research facility, equipped for group activities and video presentations. To reduce parent absences, infant care was offered in nearby rooms during the sessions by student assistants. All partners of the mothers were invited to participate, with 91 (30.6%) accepting. To maintain consistent attendance, parents who anticipated missing more than two sessions were advised to enroll in a later group. If parents missed a session, they were invited to attend a brief “brush-up”, approximately 15 min prior to the next session, where the central themes of the missed session material were reviewed.

After each session, the facilitators completed a post-session fidelity journal, designed by Circle of Security International. This tool, comprising fidelity and reflection questions, aligns with the eight chapters of the COSP™ program. It aims to assess facilitator adherence to the intervention goals in each chapter, their ability to engage parents in reflective dialogs, provide a “holding environment” in the group, and address relational ruptures with parents. Additionally, all facilitators received ongoing supervision led by D. Quinlan, the developer of the fidelity journal, and JSN (2nd author), who is the Danish COSP™ trainer and certified fidelity coach. The fidelity journal was the basis for these supervision sessions. Finally, group sessions were recorded for video-review in supervision sessions, in conjunction with the fidelity journal.

Measures

Primary outcome

Maternal Sensitivity. The Coding Interactive Behavior (CIB; Feldman, Reference Feldman1998), which is a global rating system for social interactions, was used to assess maternal sensitivity. CIB was coded during five minutes of free-play during the home visit and five minutes of free-play in the university laboratory. The families were instructed to play and interact with their child as they normally would with whatever toys they had in the home at the baseline visit and with provided age-appropriate toys during the follow-up. The measure consists of 33 items: 18 relating to the parent’s behavior (e.g., ‘Acknowledging’), eight relating to the child (e.g., ‘Initiation’), five to the dyad (e.g., ‘Dyadic Reciprocity’), and two representing the lead-lag of the interaction. All items are rated from 1 (minimal level of behavior) to 5 (high level of behavior) with half-point increases. In all, six coders were involved in coding all RCT videos. All coders were blind to the allocated condition of the mothers. It was not possible for the coders to be blind to assessment timepoint, as the baseline assessment took place in the families’ own home, and the follow-up assessment took place at the university. At baseline, 19.7% of the sample was coded for reliability with inter-rater agreement being 91.3% (i.e., the percentage of agreement between ratings for each item). The coders could deviate no more than 1 point to be considered in agreement. Inter-rater reliability was calculated based on an absolute agreement one-way random effects model (Koo & Li, Reference Koo and Li2016), showing excellent reliability (ICC = .97, 95% CI [.96; .97]). Cohen’s κ = .90, indicating almost perfect reliability. At follow-up, 20.9% of the sample was coded for reliability and had an inter-rater agreement of 95.3%. Inter-rater reliability still showed excellent reliability (ICC = .98, 95% CI [.98; .98]), and Cohen’s κ = .94, also indicating almost perfect reliability. The sensitivity composite was based on a recent validation study of the CIB in a subsample of the project (Stuart et al., Reference Stuart, Egmose, Smith-Nielsen, Reijman, Wendelboe and Væver2023) and consisted of the average of the following nine items: ‘Adaptation Regulation’, ‘Resourcefulness’, ‘Consistency of Style’, ‘Parent Supportive Presence’, ‘Overriding – Intrusiveness’ (reverse coded), ‘Acknowledging’, ‘Appropriate Range of Affect’, ‘Anxiety’ (reverse coded), and ‘Tension’ (reverse coded). Higher scores reflect higher sensitivity.

Secondary outcomes

Maternal Reflective Functioning. The Parental Reflective Functioning Questionnaire (PRFQ; Luyten et al., Reference Luyten, Mayes, Nijssens and Fonagy2017) is a self-report 18-item questionnaire used to assess maternal reflective functioning. In the present study, we use the recently validated infant version (PRFQ-I; Wendelboe et al., Reference Wendelboe, Smith-Nielsen, Stuart, Luyten and Væver2021). This version entails 15 of the 18 items from the PRFQ. Items are rated on a Likert scale from 1 (“completely disagree”) to 7 (“completely agree”). The items are averaged into three subscales: 1) Prementalizing (PM; 3 items), non-mentalizing modes with the mother having difficulties recognizing/acknowledging her child’s mental states (e.g., “My child cries around strangers to embarrass me”); 2) Certainty of Mental States (CMS; 6 items), how certain the mother is in attributing mental states to the child (e.g., “I can always know why my child acts the way he or she does”); and 3) Interest and Curiosity (IC; 6 items), the mother’s interest in understanding her child’s mental states (e.g., “I am often curious to find out how my child feels”). Higher scores on PM indicate less optimal reflective functioning, with higher scores on CMS and IC reflecting more optimal reflective functioning.

Child-Mother Attachment Quality. Infant-mother attachment quality was assessed with the Strange Situation Procedure (SSP; (Ainsworth et al., Reference Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters and Wall1978a), which is a well-validated and commonly used research experiment for evaluating the quality of attachment relationships when infants are 11–24 months of age (e.g., Madigan et al., Reference Madigan, Fearon, van IJzendoorn, Duschinsky, Schuengel, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Ly, Cooke, Deneault, Oosterman and Verhage2023). Through experimental manipulations aimed at causing mild-to-moderate stress in the child, the procedure activates the child’s attachment behavioral system, and the organization of their attachment behavior in relation to a primary caregiver (here, the birth mother) can be observed. The experimenter asked mothers not to breastfeed their children or use a pacifier during the procedure. Briefly, the procedure was that the experimenter showed the child and mother into a laboratory room, where multiple age-appropriate toys were ready on the floor for the child to play with. After 3 minutes, an unfamiliar researcher (the “stranger”) entered and sat down. After the stranger had interacted with first the mother and then the infant, the mother got up to quietly leave the room. This first separation of mother and child would last for 3 minutes, unless the child cried intensely and could not be soothed by the stranger over the course of more than 15 seconds. The mother then reentered the room indicating the beginning of the first reunion, the mother interacted with her child as felt natural to her, and as soon as she thought was possible attempted to get the child to play. The stranger quietly left the room when the mother and child were reunited. After 3 minutes upon the mother’s return, the mother got up, said goodbye to her child, and left the room. The child was alone in the room indicating the beginning of the second separation; if children started crying and did not calm down within 15 seconds, the episode was cut short. If the child was still crying at the end of the first reunion, they were not left alone; the stranger would come in and gently take the child from the mother, who would leave. Finally, the mother reentered the room indicating the beginning of the second reunion and she was asked to behave similarly to the first reunion.

SSPs were scored by IE (3rd author) and SR (4th author). IE passed the Minnesota reliability test for coding the Ainsworth et al. (Reference Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters and Wall1978a) classifications (ABC) and the Main and Solomon (Reference Main, Solomon, Greenberg, Cicchetti and Cummings1990) disorganized (D) classification. SR passed the Minnesota reliability test for coding the Ainsworth et al. (Reference Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters and Wall1978a) ABC classifications and obtained 71% agreement with expert coders on the Main and Solomon (Reference Main, Solomon, Greenberg, Cicchetti and Cummings1990) D classification. Based on a random selection of 44 videos, interrater agreement for ABC classification was Cohen’s κ = .74 (agreement on 38/44 videos, 86%). Interrater agreement for ABCD classification was Cohen’s κ = .67 (agreement on 35/44 videos, 80%). Particularly complex cases, about which IE and SR could not come to a clear conclusion (n = 14), were additionally coded by certified coder Dr Tommie Forslund (Stockholm University). These cases were discussed, and a consensus on their final classification was reached. Seven SSPs were excluded: Five because the procedure had to be terminated before completion and two due to technical errors. All coders were blind to the allocated condition of the mothers. For the analyses, we used both the four-way classification, the continuous D score, and a continuous score for attachment security based on Richters et al. (Reference Richters, Waters and Vaughn1988) (modified and validated by van IJzendoorn & Kroonenberg, Reference van IJzendoorn and Kroonenberg1990) that has been used in several studies; (Luijk et al., Reference Luijk, Roisman, Haltigan, Tiemeier, Booth-LaForce, van IJzendoorn, Belsky, Uitterlinden, Jaddoe, Hofman, Verhulst, Tharner and Bakermans-Kranenburg2011; Tharner, Luijk, Raat, et al., Reference Tharner, Luijk, Raat, IJzendoorn, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Moll, Jaddoe, Hofman, Verhulst and Tiemeier2012; Væver et al., Reference Væver, Cordes, Stuart, Tharner, Shai, Spencer and Smith-Nielsen2022). For the continuous D score, higher scores reflect more attachment disorganization. For the continuous attachment security variable, higher scores reflect more attachment security, with scores ≥ 0 indicating secure attachment.

Risk condition

Maternal Depressive Symptoms. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS; Cox et al., Reference Cox, Holden and Sagovsky1987) is used to screen for symptoms of PPD occurring in the past seven days. It consists of 10 items (rated on a 4-point Liker scale) related to mood and feelings. Total scores range from 0 to 30 with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms. In the current study, the Danish version of the EPDS was administered by the health visitors to indicate possible PPD (using a cutoff of 10 or above).

Infant Social Withdrawal. The Alarm Distress Baby Scale (ADBB; Guedeney & Fermanian, Reference Guedeney and Fermanian2001) is a short observer-rated instrument used to assess infant social withdrawal. It consists of eight items, rated 0–4: facial expression, eye contact, general level of activity, self-stimulation gestures, vocalization, briskness of response to stimulation, capacity to engage in a relationship with the observer, and capacity to attract and maintain the observer’s attention. The items are summed to a total score, with higher scores reflecting more social withdrawal. We used a cutoff of 5 and above to indicate elevated levels of social withdrawal. Previous research has shown a cutoff score of 5 to demonstrate acceptable levels of sensitivity and specificity (De Rosa et al., Reference De Rosa, Curró, Wendland, Maulucci, Maulucci and Giovanni2010; Guedeney & Fermanian, Reference Guedeney and Fermanian2001; Lopes et al., Reference Lopes, Ricas and Mancini2008). To ensure that the infant’s display of social withdrawal is not a transient phenomenon, the ADBB should be repeated within 1–2 weeks, when a child scores above cutoff. Persistent social withdrawal is confirmed when the child has scored above cutoff on two consecutive assessments. The infant’s interaction with the observer was video-recorded, and 20% were randomly selected to be coded for inter-rater reliability by a psychologist trained and certified in the ADBB. Inter-rater reliability was shown to be good (ICC = .79; 95% CI [.72; .84], Cohen’s κ = .66). It is important to note that the reliability coder only had the video-recordings to code the ADBB, while the observer could use the entire home visit to base their rating of the infant’s social withdrawal behaviors.

Covariates

In the analyses, we controlled for the following background information: child sex, child age in months at baseline, maternal age at birth, maternal marital status, maternal educational level, maternal employment status, and whether the mothers in the last months had had alcohol and/or drugs or whether they had smoked during their lifetime. We also controlled for maternal PPD assessed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Disorders – Research Version (SCID-5-RV; First et al., Reference First, Williams, Karg and Spitzer2015), maternal personality disorder assessed with the Standardized Assessment of Personality Abbreviated Scale (SAPAS; Moran et al., Reference Moran, Leese, Lee, Walters, Thornicroft and Mann2003), maternal attachment style assessed with Experiences in Close Relationships – Revised (ECR-R; Fraley et al., Reference Fraley, Waller and Brennan2000), maternal experiences of traumatic events in her childhood assessed with the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE; Felitti et al., Reference Felitti, Anda, Nordenberg, Williamson, Spitz, Edwards, Koss and Marks1998), and family functioning assessed with the McMaster Family Assessment Device (FAD; Epstein et al., Reference Epstein, Baldwin and Bishop1983).

Statistical analyses

The analyses were pre-registered in the protocol paper (Væver et al., Reference Væver, Smith-Nielsen and Lange2016). All analyses were done using the lme4 package (Bates et al., Reference Bates, Maechler, Bolker and Walker2015) in R. A power analysis (as reported in the protocol paper (Væver et al., Reference Væver, Smith-Nielsen and Lange2016)) showed that 250 participants were needed to provide 90% power to detect a medium effect of the treatment. As dropouts were expected, recruitment aimed at including 314 families. We ended up with 297 participants, indicating that the study should be adequately powered to detect a medium effect size. However, we did also have a larger number of dropouts than expected, resulting in a complete case sample of 234 participants. As this was more than 5% of the sample being missing, we did not run complete case analyses. Instead, missing data was handled with multivariate imputation by chained equations (van Buuren & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, Reference van Buuren and Groothuis-Oudshoorn2011) with the mother’s age, educational level, marital status, and level of depressive symptoms used as predictors. Imputation was done separately for RCT-groups (i.e., COSP™/CAU).

All hypotheses were tested using mixed models to account for the correlation induced by mothers attending the same COSP™ group. Nesting was handled by a variable detailing which of the 36 COSP™ groups, the individual mother had attended. As we did not have specific information on the treatments in the CAU group, they were all nested together. We tested both under the intention-to-treat principle and treatment-as-given (i.e., if the mother had participated in four or fewer COSP™ sessions, she was moved to the CAU group). Under each of the two test principles, we ran two models. In the first model, we only included the baseline measure of the outcome. In the second model, we included the baseline measure and a range of family characteristics as covariates (risk condition, child sex, child age at baseline, mother’s age at birth, marital status, educational level, employment status, lifetime depression status, attachment anxiety, attachment avoidance, personality disorder, family functioning, alcohol/drug/smoking use at baseline, depression status at follow-up, and number of adverse childhood experiences). This resulted in four models being run for each outcome.

For the primary outcome, maternal sensitivity, we did linear mixed models with RCT-group as the predictor. A linear mixed model was also fitted for the secondary outcomes, maternal reflective functioning and the continuous measures of child attachment. Due to the child’s age at inclusion, we did not have baseline assessments of child attachment and did thus not control for it. For child attachment classification, we ran three logistic mixed models with secure attachment (B) as the reference group.

We tested two variables as moderators. The first was risk condition (i.e., the inclusion reason being either high EPDS, high ADBB, or both). The second moderator variable was disadvantaged family status (i.e., a binary variable being low educational level AND no employment (=1) compared to every other combination of educational level and employment status (= 0)). We investigated if these two variables had a moderating effect on the association between RCT-group and outcome by adding them as separate interaction effects in their own models to the analyses described above.

As described, some families had a long waiting period from last COSP™-session to their follow-up assessment. We do not have any information on when the families started and finished their different CAU treatments. In post hoc exploratory analyses, we added the waiting period from baseline assessment to follow-up assessment (CAU: M = 325.14, SD = 60.81, range = 146–430; COSP™: M = 325.57, SD = 68.65, range = 142–561) as a covariate to the abovementioned analyses.

All reported p-values are two-tailed and tested at a significance level of .05.

Results

Descriptive statistics

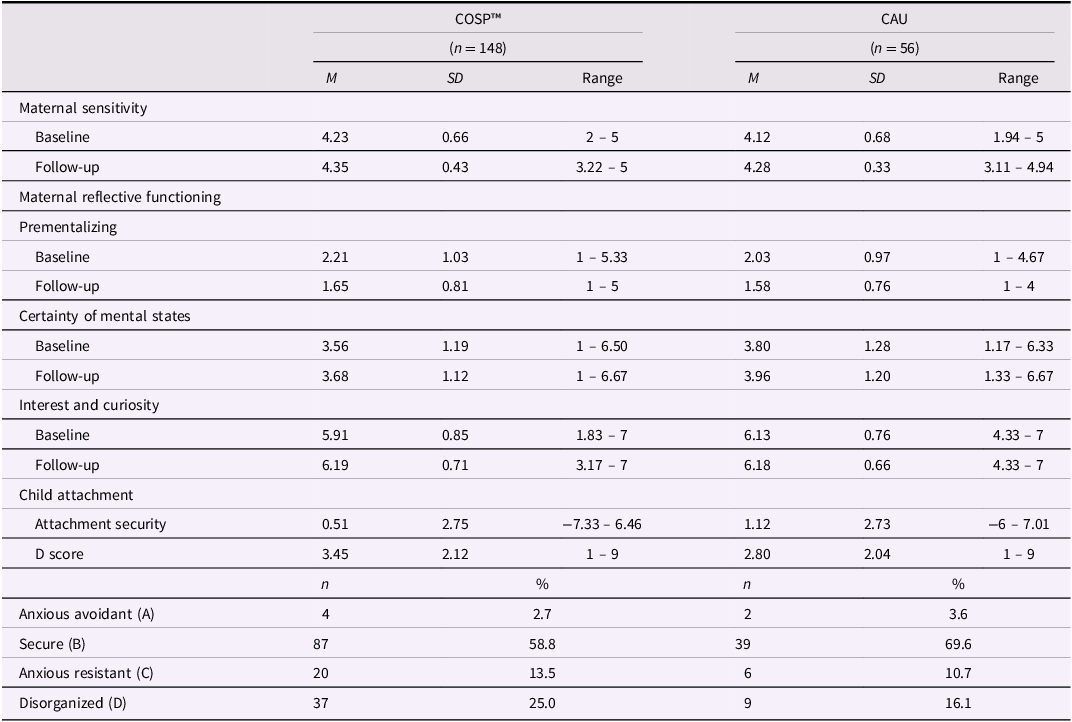

Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 3. The mothers had high sensitivity scores in both groups already at baseline, as the maximum possible score was 5. Scores on the PRFQ could possibly range from 1–7, and the mothers scored optimal on the PRFQ at baseline; low scores on Prementalizing, moderate scores on Certainty of Mental States and high scores on Interest and Curiosity. There were very few children with avoidant attachment classifications, and in both groups, the majority of the children were securely attached to their mother. Descriptive statistics in Tables 1, 2, and 3 are based on complete cases, while in Table 4, the reported estimates are based on multiple imputed data. The attendance rate of the mothers in COSP™ was on average 7.48 (SD = 2.87) sessions. In the supplementary materials (Table S2), a correlation matrix between the outcomes and the covariates shows that there were few significant associations between the variables.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics of the outcome variables

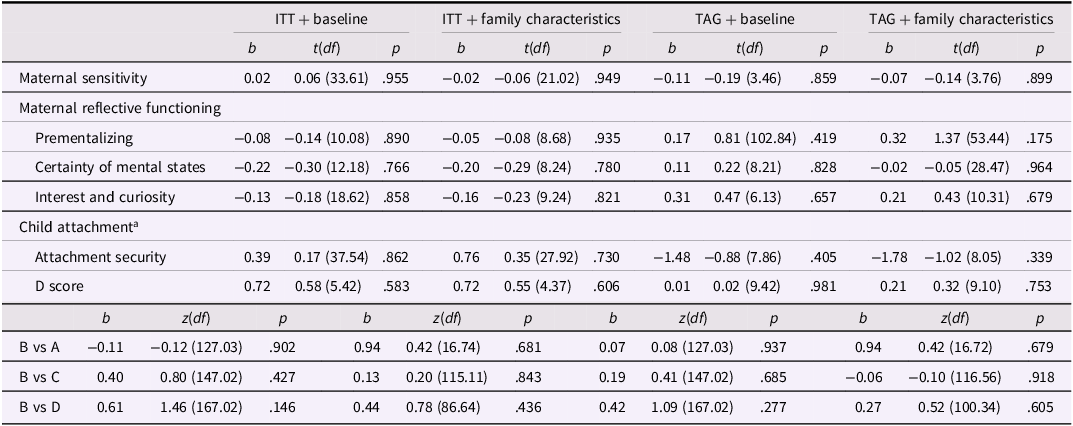

Table 4. Effect of RCT-group (reference group is CAU) on the primary and secondary outcomes in the analyses

Note. ITT = intention-to-treat; TAG = treatment-as-given. aWe did not have baseline assessment of child attachment and thus did not control for it in the models.

Attrition analyses

As seen in the flowchart (Figure 1), we had a high percentage of dropout from baseline to follow-up: 15.3% in COSP™ and 31% in CAU. This was a significant difference (p = .014), indicating that there were 2.1 higher odds for dropping out in the CAU group compared to the COSP™. Binary logistic regression analyses did not find any of the baseline measures of our outcome variables to be significantly related to dropout (all ps ≥ .281) or the background variables gestational age, maternal age at birth, parity, employment status, educational level, relationship status, ethnicity, depression status (current or lifetime), alcohol, drugs, or smoking, child gender, child age, or risk condition (i.e., included in RCT based on EPDS and/or ADBB scores), (all ps ≥ .135). Further, maternal personality disorder, attachment style, or adverse childhood experiences did also not predict dropout (all ps ≥ .081). However, family functioning was a significant predictor (p = .041), indicating that the more dysfunctional the family was, odds were 0.5 lower for dropping out. This association was not significantly different in the two RCT groups (OR = 1.19, p = .067). A sensitivity analysis of complete cases revealed no differences in significant estimations (all ps ≥ .060) as compared to the multiple imputation estimates presented in the next section. Taken together, this indicates that dropout and data was missing at random, and that the subsequent outcome analyses estimated with multivariate imputation by chained equations were not biased.

Outcome analyses

The results of the mixed models are presented in Table 4. There were no significant differences between the COSP™ and CAU group on neither the primary nor secondary outcomes (all ps ≥ .146).

There was no significant interaction between RCT-group and risk condition in any of the four models or on any of the outcomes (all ps ≥ .139). The same applied for the interaction between RCT-group and disadvantaged family status (all ps ≥ .322).

Controlling for the waiting time from baseline to follow-up assessment did not significantly affect any of the results (all ps ≥ .072)

Discussion

The present study investigated the efficacy of combining the COSP™ with CAU versus CAU alone in families with infants, who are affected by maternal PPD and/or infant social withdrawal. Contrary to our hypotheses, we found no differences between the two groups on any of the three outcomes. These null-findings are in line with the results from other RCTs, published after the current study was initiated, where either few (Cassidy et al., Reference Cassidy, Brett, Gross, Stern, Martin, Mohr and Woodhouse2017; Røhder et al., Reference Røhder, Aarestrup, Væver, Jacobsen and Schiøtz2022; Zimmer-Gembeck et al., Reference Zimmer-Gembeck, Rudolph, Edwards, Swan, Campbell, Hawes and Webb2022) or no significant effects of the COSP™ (Risholm Mothander et al., Reference Cassidy, Brett, Gross, Stern, Martin, Mohr and Woodhouse2018) were found.

Ceiling effects of sensitivity and parental reflective functioning

The lack of observed effects may not be surprising given the high baseline levels of maternal sensitivity and parental reflective functioning. Participating mothers demonstrated high baseline scores in sensitivity and had optimal scores across the three subscales of the PRFQ. Already high-functioning individuals may affect our capacity to detect notable improvements through the COSP™ at a group level. Further, following the notion of the “good enough” parent (Winnicott, Reference Winnicott1964), striving for perfection in parenting may not only be unnecessary but unwarranted in terms of supporting healthy parent-child relationships.

However, assessing maternal sensitivity in a free play situation and parental reflective functioning using a questionnaire may not have been the most optimal methods. Research suggests that assessing sensitivity in stress-inducing situations may better capture individual differences in sensitivity, since it is typically more challenging for parents to maintain sensitivity during child distress (Branger et al., Reference Branger, Emmen, Woudstra, Alink and Mesman2019; Dittrich et al., Reference Dittrich, Fuchs, Führer, Bermpohl, Kluczniok, Attar, Jaite, Zietlow, Licata, Reck, Herpertz, Brunner, Möhler, Resch, Winter, Lehmkuhl and Bödeker2017; Leerkes et al., Reference Leerkes, Blankson and O’Brien2009). Thus, the free-play context employed in our study may have prevented us to identify potential challenges faced by the mothers in responding sensitively to distress, potentially contributing to the ceiling effect observed in maternal sensitivity assessments. Similarly, since parental reflective functioning can be influenced by the context, particularly in situations involving infant crying and distress (Rutherford et al., Reference Rutherford, Goldberg, Luyten, Bridgett and Mayes2013, Reference Rutherford, Bunderson, Bartz, Haitsuka, Meins, Groh and Milligan2021), evaluating this outside of direct parent-child interactions might have overlooked potential deficits in mentalizing that emerge in stressful or challenging situations. While the COSP™-protocol includes content and reflective questions about the significance of shared delight and supporting the child’s exploration, it places more emphasis on the parent’s role as a safe haven, especially regulating difficult emotions in the child. Therefore, evaluating maternal sensitivity and reflective functioning in a context that mildly stresses both the mother and child could have aligned more closely with the objectives of COSP™, providing a more suitable setting to observe and measure the intended outcomes of the intervention.

Distributions of attachment classifications

The distribution of infant-mother attachment classifications in our study is in line with the recent meta-analysis by Madigan et al. (Reference Madigan, Fearon, van IJzendoorn, Duschinsky, Schuengel, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Ly, Cooke, Deneault, Oosterman and Verhage2023). While we found relatively high frequencies of disorganized attachment (22.5%), it is still similar to the meta-analysis (23%), and the meta-analysis further indicates that there is a higher rate of disorganized attachment in samples with psychopathology. Our rate of secure attachment was 61.8% compared to 52% in the meta-analysis, and resistant was almost identical (in the present study, it was 12.7%, in the meta-analysis 10.2%). It was only our rate of avoidant classification that was very low (2.9%) compared to the meta-analysis (14.7%). However, Madigan et al. (Reference Madigan, Fearon, van IJzendoorn, Duschinsky, Schuengel, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Ly, Cooke, Deneault, Oosterman and Verhage2023) also find that the rate of avoidant attachment is decreasing, and that it is only particularly high in samples of sociodemographic risk. Our distribution may, thus, reflect that the sample generally exhibited a high level of resources. Nevertheless, the lack of impact of COSP™ on increasing the proportion of attachment security calls for critical reflections on its efficacy in altering the relational dynamics. The only other study examining effects of the COSP™ on infant-mother attachment quality also reported no main effects of the intervention on attachment quality (Cassidy et al., Reference Cassidy, Brett, Gross, Stern, Martin, Mohr and Woodhouse2017). The standard COSP™ format with pre-produced video-vignettes combined with group reflections may not offer sufficient support to prevent attachment disorganization and insecurity, perhaps because it does not effectively support parents in “translating” conceptual learnings into behavioral changes during interactions with the child. To improve parent-child relationship quality, it may be necessary that the intervention is dyadic in that it includes both parent and child rather than only including the parent in the intervention as is the case with COSP™. Indeed, previous interventions that have facilitated a decrease in rates of disorganized attachment include both parent and child in the actual intervention in addition to individualized video-feedback (e.g., Bernard et al., Reference Bernard, Dozier, Bick, Lewis-Morrarty, Lindhiem and Carlson2012; Juffer et al., Reference Juffer, Bakermans-Kranenburg and van IJzendoorn2005; Moss et al., Reference Moss, Dubois-Comtois, Cyr, Tarabulsy, St-Laurent and Bernier2011). Likewise, the intensive 20-week version of the COS intervention includes video feedback, thereby bringing the child into the therapeutic setting, as well as individualized treatment planning and showed significant reductions in the proportion of children with a disorganized attachment in a pre-post-study (Hoffman et al., Reference Hoffman, Marvin, Cooper and Powell2006).

Target population: mothers suffering from postpartum depression and infants

The participants in this RCT were identified as at-risk due to PPD and/or infant social withdrawal. As these factors have previously been associated with poorer mother-infant relationship (e.g., Bernard et al., Reference Bernard, Nissim, Vaccaro, Harris and Lindhiem2018; Dollberg et al., Reference Dollberg, Feldman, Keren and Guedeney2006; Madigan et al., Reference Madigan, Fearon, van IJzendoorn, Duschinsky, Schuengel, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Ly, Cooke, Deneault, Oosterman and Verhage2023), we assumed that this was an ideal target group to benefit from COSP™. However, one point of note is that almost all mothers in the CAU group received some form of psychotherapy where they may have touched upon subjects such as how to be sensitive and meeting their children’s emotional needs. Røhder et al. (Reference Røhder, Aarestrup, Væver, Jacobsen and Schiøtz2022) previously attributed their lack of significant findings to this fact.

Additionally, the content of the COSP™ might not have been well-aligned with the needs of the participants in this study, where the majority of mothers had been diagnosed with major depression. Indeed, a recent systematic review found that intervention approaches focusing on treating or preventing PPD alone or in combination with a focus on the mother-child relationship were most effective for reducing PPD (Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Hameed and Avan2023). Furthermore, as discussed, at a group-level, the mothers already scored quite high on sensitivity at baseline, which may indicate that, rather than relationship issues, depression was the primary challenge for most mothers in the current sample. While some previous research has indicated that PPD negatively affects the mother-child relationship (Bernard et al., Reference Bernard, Nissim, Vaccaro, Harris and Lindhiem2018; Śliwerski et al., Reference Śliwerski, Kossakowska, Jarecka, Świtalska and Bielawska-Batorowicz2020), other studies found negative effects only when PPD occurred in combination with other risk factors such as personality disorder (e.g., Emmanuel & St John, Reference Emmanuel and St John2010; Kingston et al., Reference Kingston, Tough and Whitfield2012; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Pallant and Negri2006; Smith-Nielsen et al., Reference Smith-Nielsen, Tharner, Steele, Cordes, Mehlhase and Vaever2016; Wendelboe et al., Reference Wendelboe, Smith-Nielsen, Stuart, Luyten and Væver2021). As seen in the correlation matrix (Table S2), we did not find any significant associations between personality disorder and the study outcomes, but future studies should investigate personality disorder as a potential moderator, as there may be subgroups of mothers who benefitted from COSP™. Therefore, many of the mothers in the present study might have benefited more from an intervention focusing on their depression, whereas others might have benefitted from combining COSP™ with elements that target the depression.

Yet another possible reason for the lack of effectiveness of the COSP™ in this study could be due to its implementation in families primarily with infants aged between two and four months at the beginning of the intervention. The COSP™ manual (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Hoffman and Powell2009), which was revised after the initiation of the present RCT, in fact advises against enrolling parents of infants younger than four months. This is because parenting challenges at these earlier ages differ significantly, focusing more on managing immediate needs, such as crying regulation, sleep, and feeding, rather than the issues emphasized by COSP™. Consequently, offering COSP™ to families with infants included before four months of age may not have been the most appropriate intervention choice.

Moderator analyses

While we were sufficiently powered to detect a main effect of COSP™ on maternal sensitivity (Væver et al., Reference Væver, Smith-Nielsen and Lange2016), like most RCTs, we were underpowered to detect moderating effects (cf. Rothwell, Reference Rothwell2005). However, to tailor specific interventions to specific populations, moderator analyses are imperative in identifying what works for whom. Therefore, we explored whether risk inclusion (i.e., only PPD or infant social withdrawal or both) and disadvantaged family status moderated effects of COSP™ but found no significant moderating effects. While this could be explained by lack of statistical power, it could also be that the risk inclusion and disadvantaged family status are not relevant moderators particularly in our sample: The vast majority of the sample was included based on PPD, and very few families were classified as disadvantaged. In future studies, we will explore other potential moderators, such as maternal attachment style and depression symptom severity, which moderated effects of COSP™ on child attachment in the Cassidy et al. (Reference Cassidy, Brett, Gross, Stern, Martin, Mohr and Woodhouse2017) study.

Limitations

In addition to the limitations already discussed, our study has three major limitations to consider. Firstly, the dropout rate in the Care as Usual (CAU) group from baseline to follow-up was higher than anticipated. Although a dropout rate of 20% in each group was expected (Væver et al., Reference Væver, Smith-Nielsen and Lange2016), 31% dropped out of the CAU group (vs. 15% in the COSP™ group). We did missing data imputation to retain power for our analyses. Nonetheless, it is critical to acknowledge that such imputations rely on the data from participants who remained, which might not accurately represent the characteristics or outcomes of those who withdrew from the study. Additionally, there is a possibility that the participants who completed the follow-up assessment were among the more well-functioning families, potentially introducing a bias in the observed outcomes, especially in the CAU group.

Secondly, our study is limited in terms of generalizability. Despite being identified as at-risk, the families in our study were well-resourced. This was also evident in their high levels of sensitivity and parental reflective functioning at baseline. This suggests that our findings may not extend to populations facing more severe socioeconomic challenges or those with low levels of mentalizing and sensitivity at baseline. The resilience factors present in our sample could therefore differ significantly from those in more disadvantaged contexts, where external stresses might overshadow intrinsic familial strengths.

Thirdly, some families had a longer waiting period between the last COSP™ session and the follow-up assessment. This was particularly true for families whose infants were only two months old at baseline, enrolled in a COSP™ group shortly after allocation, and required to wait until their infant reached at least 11 months for the SSP/follow-up assessments to be conducted. While we controlled for the waiting time and did not find it to have any significant impact on the results, it is nonetheless important to consider the timing of the post-intervention assessment. Cassidy et al. (Reference Cassidy, Brett, Gross, Stern, Martin, Mohr and Woodhouse2017) speculate that their lack of significant findings may be due to them having the assessment too close to the last COSP™ session to be able to capture any meaningful effects of changes in parenting and attachment relationships. In that line of thinking, our own non-significant results may also then be considered short/medium-term effects, and future research should investigate if long-term follow-up assessments detect any significant effects of COSP™.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the present RCT found no effects of the COSP™ on maternal sensitivity and reflective functioning, or infant-mother attachment when comparing COSP™ as an add on to CAU versus only CAU. We posit that more individualized intensive interventions are required to facilitate changes. Our null-findings invite considerations on the applicability and targeted population for interventions like COSP™, emphasizing the importance of precise participant selection to identify those who might benefit most from such interventions. It also underscores the need for future research to consider baseline functioning as a critical factor in the design and evaluation of parenting interventions, ensuring that they are tailored to meet the specific needs of the population they intend to serve.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579425000112.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all of the health visitors and families who participated in the study. We would also like to thank the many employees and student assistants at the Center for Early Intervention and Family Studies who have helped with data collection and coding. We would like to thank Dr Tommie Forslund for helping to code the SSP data.

Funding statement

The project was funded by the charitable foundation Tryg Foundation (Grant ID no 107616).

Competing interests

ACS, JSN, IE, SR, KIW, MS, and MSV are employed at the Center for Early Intervention and Family Studies where training in the use of the ADBB scale is offered as part of the continuing education program at the University of Copenhagen. JSN and KIW are both certified fidelity coaches in the Circle of Security (COS) intervention being tested in the current project. JSN is the Danish COS-Parenting and COSP-Classroom trainer.