Food and nutrition security exists when ‘all people at all times have physical, social and economic access to food, which is safe and consumed in sufficient quantity and quality to meet their dietary needs and food preferences, and is supported by an environment of adequate sanitation, health services and care, allowing for a healthy and active life’( 1 ). The determinants of food insecurity are multifactorial and complex, occur at multiple levels (the individual, social and environmental), and include poverty, social and economic disadvantage, individual characteristics and the political and social environments. Food insecurity can affect all stages of the lifespan( Reference Weinreb, Wehler and Perloff 2 – Reference Radermacher, Feldman and Bird 5 ), resulting in poor dietary intakes and negative health consequences( Reference Girard and Sercia 6 – Reference Tarasuk 11 ). These outcomes place significant burden on health-care systems, thus food insecurity is a significant issue for individuals, households, communities and nations alike, yet there exists no internationally accepted measurement of individuals’ and households’ food security. Accurate measurement of food security is imperative to understand the magnitude of the issue and to identify specific areas of need, in order to effectively tailor policies and interventions for its alleviation.

The definition encompasses four hierarchical dimensions which are integral to achieve food security. ‘Availability’ refers to a reliable and consistent source of enough quality food for an active and healthy life. At a macro level this has been the primary focus of nation-states; however, simply increasing production is not enough to ensure availability at a household level. The availability of food may include home food production, transport systems to ensure food is available at source points away from where it is grown, and exchange systems for food. Food needs to be available in socially acceptable ways, which meet the definition of human dignity. ‘Food availability’ is realized when people have enough food, of sufficient nutritional quality, available( Reference Gross, Schoeneberger and Pfeifer 12 ). Availability does not necessarily predict access. ‘Access’ acknowledges the resources required in order to put food on the table; this could be economic or physical (transport). It refers to the food needed by all household members to meet dietary requirements and food preferences and to achieve and maintain optimal nutritional status. This takes into consideration prioritization of food by the household over other goods and services as well as intra-household distribution of food. ‘Food access’ requires food availability to be established for it to be achieved, and it is attained when people have adequate economic resources and sufficient physical access to food( Reference Gross, Schoeneberger and Pfeifer 12 ). ‘Utilization’ refers to the intake of sufficient and safe food which meets individual physiological, sensory and cultural requirements. It also refers to physical, social and human resources to transform food into meals. It encompasses food safety but also sanitary and hygienic conditions. ‘Food utilization’ centres on people’s ability to choose nutritionally adequate foods and their ability and resources to safely prepare and store them( Reference Barrett 13 ). ‘Stability’ recognizes that food insecurity can by transitory, cyclical or chronic. ‘Stability over time’ affects the three aforementioned factors through seasonal and temporary change( Reference Gross, Schoeneberger and Pfeifer 12 ). Food insecurity therefore may occur when access to or availability of safe, culturally appropriate and nutritious foods is compromised, or when these foods cannot be obtained via socially acceptable means. However, if food security is to exist, then availability, access and utilization need to be stable over time and not be subject to weather variations, food price shifts or civil conflict( Reference Ecker and Breisinger 14 , Reference Carletto, Zezza and Banerjee 15 ).

The contextual nature and complexity of the issue, combined with the practical considerations of data collection, may make the measurement of food security problematic. Given these complexities, multi-item tools are likely to be able to capture the full extent of the food security spectrum; however, such tools are often long and have significant time and financial implications for data collection, particularly in large-scale monitoring efforts( Reference Masters, Coles-Rutishauser and Webb 16 ). A systematic review by Marques et al. in 2014, which searched the literature up to 2011, identified the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) Food Security Survey Module (FSSM) as the only tool in the literature in which psychometric properties had been substantially evaluated, having undergone rigorous testing among a variety of population groups( Reference Marques, Reichenheim and de Moraes 17 ). The FSSM measures household food insecurity. It is an eighteen-item measure that assesses the dimension of food access through financial resources, with questions investigating concern about and actually running out of food and instances of reducing amounts and quality of food in a household. The FSSM was developed based on two early instruments: the Community Childhood Hunger Identification Project (CCHIP) tool and the Radimer/Cornell tool( Reference Carlson, Andrews and Bickel 18 ). Despite its validity and reliability, the FSSM may not fully capture the extent and magnitude of food security, as its measurement is limited to one dimension of food security( Reference Marques, Reichenheim and de Moraes 17 , Reference Bickel, Nord and Price 19 ). In addition, it has not been validated in certain populations, so may not be the most appropriate tool for some groups. There is a need to more fully explore the tools that are available to assess food security, particularly the dimensions they assess.

The present review aimed to update and build on the previous Marques review( Reference Marques, Reichenheim and de Moraes 17 ) to identify all reliable and valid multi-item tools, separate to the FSSM, and the dimensions of food security they assess.

Methods

Using the PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) framework( Reference Moher and Tricco 20 ), the present review aimed to answer the question ‘In developed countries, what tools are available for measuring food security, in addition to the USDA FSSM, and what dimensions of food security do they assess?’ Describing the prevalence of food insecurity measured by these tools across different countries was beyond the scope of the review.

Eligibility criteria

To avoid unnecessary repetition of the findings of the Marques review( Reference Marques, Reichenheim and de Moraes 17 ) that had no search date limit, studies that reported on the FSSM tool were excluded from the present review. Given the variations in both determinants and outcomes of food insecurity between developed and developing countries, and subsequently potential differences in measurement, studies in developing countries were omitted to ensure issues of famine and war did not influence measurement or findings. The authors sought to strengthen generalizability of the findings to the developed country context to support advocacy efforts around monitoring of food insecurity.

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they were conducted in developed countries, as defined by the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) member countries( 21 ), and conducted on human subjects. Studies were limited to those published in English as resource limitations prevented article translation. The search was limited to studies published from the year 1999 to current date (June 2014) to ensure newly developed tools were identified. To be included, studies were required to have as their main objectives to measure food insecurity and report on a tool that was multi-item, thus excluding single-item tools which would be unable to assess varying levels of severity of food security. Studies also had to include a tool that assessed food security in at least one of the dimensions (Table 1). All study designs were included, as well studies that measured individual-, household- or community-level food security, to allow a comprehensive scan of the use of tools.

Table 1 Systematic review inclusion and exclusion criteria

OECD, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; USDA, US Department of Agriculture.

* Articles were coded based on first relevant criteria.

Search strategy

The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) protocol, a list of key elements that must be reported when conducting a systematic review( 22 ), was followed. Five databases were searched: CENTRAL, CINAHL plus, EMBASE, Ovid MEDLINE and TRIP, due to their content specificity in health, nutrition and food. Search terms related to the terms, developed countries and tool to assess food security and its dimensions were developed (Table 2). These terms were based on search terms used in the previous systematic review( Reference Marques, Reichenheim and de Moraes 17 ) that explored food insecurity measurement. Data were limited to the searching databases with predominantly peer-reviewed literature; unpublished work or expert opinion was unlikely to contain information about the statistical validity/reliability of the instruments.

Table 2 Systematic literature review search terms and strategyFootnote †

* Truncation was used at the end of the word in all databases to retrieve all suffix variation.

† The full electronic search strategy for CINAHL database conducted on 1 June 2014 as an example: (‘food NEXT access*’ OR ‘food NEXT afford*’ OR ‘food NEXT insecure*’ OR ‘food NEXT poverty*’ OR ‘food NEXT secur*’ OR ‘food NEXT suppl*’ OR ‘food NEXT sufficien*’ OR ‘food NEXT insufficien*’ OR ‘food NEXT desert*’) AND (‘survey*’ OR ‘tool*’ OR ‘question*’ OR ‘measure*’). Limits: year, >1999; language, English; subjects, human.

Study selection

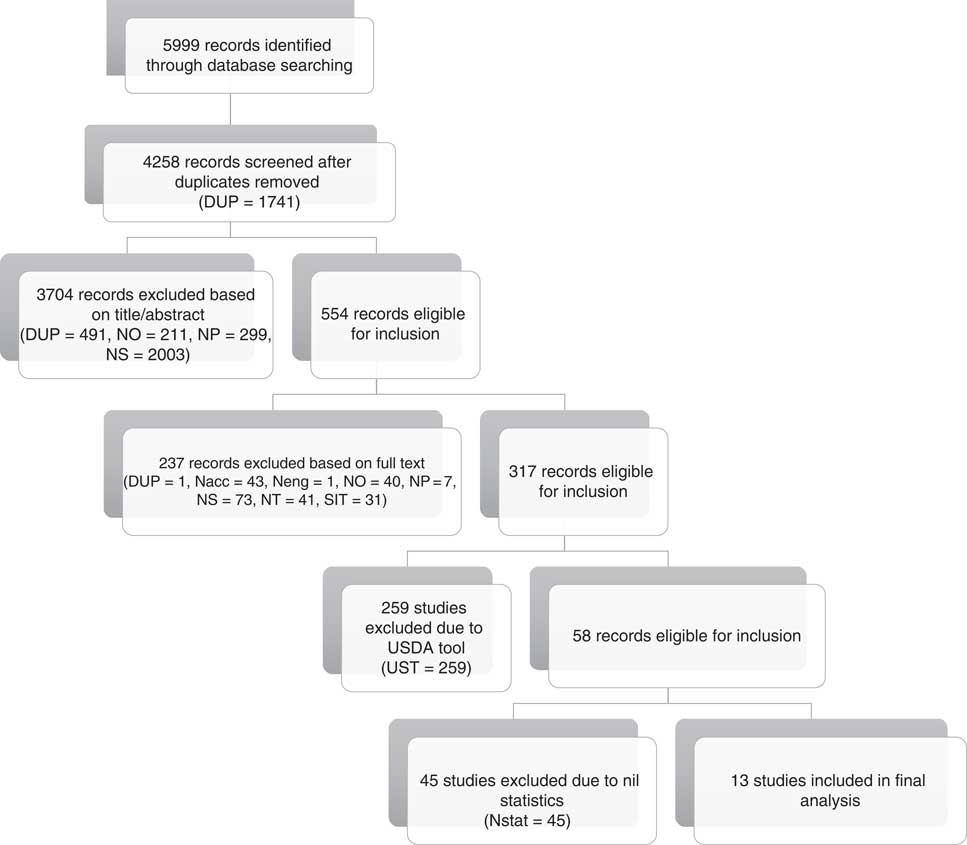

Studies were identified and subsequently included or excluded through a four-phase screening process. The number of search records and subsequent inclusion and exclusion in each phase are summarized in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 Systematic literature review study selection flowchart (DUP, duplicate study; NO, not an outcome of interest; NP, not a population of interest; NS, not a study of interest; Nacc, not an accessible study; Neng, not in English language; NT, tool not named or discussed; SIT, single-item tool; UST, US Department of Agriculture (USDA) tool; NStat, no statistical validity/reliability data)

The first phase involved screening the titles and abstracts of articles to determine inclusion and exclusion. All records identified from the search term in each database were filed and handled using EndNote X7TM, and any duplicates were removed. The title and abstract of each article were screened and, based on these, those that were deemed to tentatively meet the inclusion criteria were included; those that did not meet the inclusion criteria were assigned codes indicated in Table 1. Five hundred and fifty articles from the initial search were randomly selected to be cross-checked by two authors (C.P. and S.K.) to ensure concurrence with inclusion and exclusion criteria. Disagreements between the reviewers were discussed and settled by consensus.

The second phase involved reviewing the full text of the articles included from the first phase. In the third phase, remaining studies were divided into categories based on the food security measurement tool they utilized. Papers that used only the USDA tool were excluded (n 259). The fourth phase involved excluding studies that did not report any measures of validity or reliability (n 45). Those that remained were included in the final analysis.

Data extraction

Data extraction from the selected articles was undertaken independently by two authors, using a spreadsheet that had been designed to answer the research question. The following information was extracted: (i) source of funding/affiliation; (ii) study design; (iii) location/setting of research; (iv) population the tool had been used in; (vi) summary of main findings; (vii) name of the tool; (viii) number and type of questions in the tool; (ix) mode of delivery of the tool; (x) any modifications made to the tool; (xi) any statistical measures of reliability, validity, sensitivity or specificity; (xii) level of food security measured; (xiii) dimension of food security assessed; (xiv) time period measured; and (xv) quality of the study and risk of bias as assessed using the American Dietetic Association Evidence Analysis Manual ( 23 ) based on ten questions related to validity and scoring the study as positive, neutral or negative.

Due to the heterogeneous nature of the included studies, and the need to summarize all available tools as part of the research question, a summary of included studies was prepared( Reference Popay, Roberts and Sowden 24 ). Differences and commonalities between tools were identified and collated, and described narratively. All studies were weighted equally, despite quality ratings, given that the objective of the study was to describe all tools that attempted to measure food insecurity with some statistical integrity.

Results

Database searching recovered 5999 records. After exclusion criteria were applied, thirteen studies, describing eight different tools, were included in the final analysis (Fig. 1). The majority of the studies and tools were developed in the USA and had been used in different age groups and cultures (Table 3). The number of items in the tools ranged from two items (Townsend Food Behaviour Checklist and Hager two-item screen) to nine items (CCHIP tool; Table 3).

Table 3 Characteristics of eight tools that measure food insecurity in developed countries

All of the tools assessed the dimension of food access. The majority of tools (six in total) only assessed food security in accordance with one dimension – food access, including physical and economic resources to access food. Only the Radimer/Cornell tool enquired about anxiety around eating a good meal due to assistance required with preparing food( Reference Gollub and Weddle 25 ), and the Kuyper tool attempted to measure stability over time( Reference Kuyper, Espinosa-Hall and Lamp 26 , Reference Kuyper, Smith and Kaiser 27 ). The Radimer/Cornell tool( Reference Gollub and Weddle 25 ) also assessed the dimension of food utilization and the Kuyper tool( Reference Kuyper, Espinosa-Hall and Lamp 26 , Reference Kuyper, Smith and Kaiser 27 ) partially assessed the dimension of stability over time. Food availability was not assessed by any tools found in the present review.

Of the eight tools, three assessed individual food security, four assessed household food security and one, the Girard four-point tool, assessed both individual and household food insecurity. No individual instrument was identified that measured community food insecurity (Table 3). All studies used Cronbach’s alpha (coefficient of internal consistency) to measure reliability. The tools all yielded moderate to high reliability among the respective samples in which they were used. Only one tool (the Hager two-item screen) was compared with another direct measure of food insecurity (the USDA FSSM) with a reported 97 % sensitivity and 83 % specificity compared with the USDA FSSM( Reference Hager, Quigg and Black 28 , Reference Swindle, Whiteside-Mansell and McKelvey 29 ). Each of the tools identified had previously been validated among different population subgroups and against different factors known to be associated with food insecurity, with the findings for each tool suggesting satisfactory convergent validity for each respective measure (Table 3). It was however noted that validity was investigated for only one tool (the Cornell Child Food Security Measure). The validity for the remaining tools was based primarily on comparisons with other associated, but separate, factors. All tools relied on self-report and are therefore subjective.

Of the thirteen studies, three were unclear regarding the period of time the respondent was asked to recall, two studies asked for respondents to respond in relation to the past 12 months/past year, two incorporated a recall period spanning the previous 3 months/past few weeks, and one study asked respondents to recall experiences from their childhood. All studies sampled from vulnerable population subgroups that were more likely to be at risk of food insecurity, including older adults, adults with HIV, adults on low incomes and children from low-income families.

Discussion

The present systematic literature review aimed to collate all multi-item tools with statistical integrity that have been used to assess food insecurity in developed countries, separate to the FSSM, and to establish the dimensions of food security assessed by each instrument. The review found that there were eight tools – the Radimer/Cornell tool( Reference Gollub and Weddle 25 ), the Cornell Child Food Security Measure, the CCHIP tool( Reference Jimenez-Cruz, Bacardi-Gascon and Spindler 30 ), the Hager two-item screen( Reference Hager, Quigg and Black 28 , Reference Swindle, Whiteside-Mansell and McKelvey 29 ), the Girard four-point tool( Reference Girard and Sercia 6 ), the Kuyper past food security tool( Reference Kuyper, Espinosa-Hall and Lamp 26 , Reference Kuyper, Smith and Kaiser 27 ), the Household Food Security Access Scale( Reference Weiser, Bangsberg and Kegeles 8 , Reference Weiser, Hatcher and Frongillo 31 , Reference Weiser, Yuan and Guzman 32 ) and the Townsend Food Behaviour Checklist( Reference Townsend, Kaiser and Allen 33 ) – in addition to the FSSM. The main focus of food insecurity measured by these tools was on the food access dimension of food insecurity for individuals and households.

Food access has been comprehensively assessed by the available tools in developed countries, as evidenced by the present systematic review’s findings and also a previous systematic review discussing the FSSM( Reference Marques, Reichenheim and de Moraes 17 ). The FSSM provides the most comprehensive assessment of this dimension with regard to economic access to food, and is the most reliable and valid of the available tools to assess food insecurity( Reference Marques, Reichenheim and de Moraes 17 , Reference Bickel, Nord and Price 19 ). Using the FSSM, the prevalence of food insecurity in the USA and Canada has most recently been reported as 14·5 % and 12·5 %, respectively( Reference Coleman-Jensen, Nord and Singh 34 , Reference Tarasuk, Mitchell and Dachner 35 ). However, despite the initial screening question that provides opportunity to assess across the pillars of food insecurity, the focus of the remainder of the tool (the component used for scoring and classification of food insecurity status) is the limited financial ability to acquire food, which assesses only the food access dimension, leaving the remaining three dimensions unassessed and other elements of the food access dimension unexplored( Reference Nord and Hopwood 36 ). Thus it is likely that national monitoring using the FSSM underestimates the true prevalence of food insecurity.

All of the tools identified in the present review focused on the financial constraints associated with acquiring sufficient amounts of food. This is not surprising given the FSSM was developed based on two early instruments, the CCHIP tool and the Radimer/Cornell tool( Reference Carlson, Andrews and Bickel 18 ), and the fact that access to economic resources is one of the key determinants of food insecurity. By focusing mainly on the experience of running out of food, these tools are likely to identify only those households experiencing more severe levels of food insecurity, subsequently failing to identify those experiencing stress related to acquiring foods, or who may be altering the quality and quantity of foods consumed as coping mechanisms, and as such have not yet actually ‘run out of food’. As such, these tools are likely to underestimate the true prevalence of food insecurity( Reference Nolan, Rikard-Bell and Mohsin 37 ).

Addressing and preventing food insecurity efforts continues to be a challenge in developed countries( Reference Burns, Kristjansson and Harris 38 ). In adopting measures of food insecurity, practitioners and policy makers should aim to incorporate a tool that assesses the spectrum of food insecurity. This should include experiences of anxiety and running out of food, such is measured in the FSSM, and in addition questions that capture utilization, coping mechanisms and stability over time, to ensure more accurate measures of food insecurity.

The focus of the food insecurity assessment and therefore instrument integrity was on vulnerable population subgroups. While there was a range of groups represented by the identified studies, all were considered at high risk of food insecurity. These tools should be applied with caution as tools validated in one country and population will not necessarily be valid in another country or population. Populations were often specific to subgroups, such as the Girard four-point tool, which was tested only with recent immigrants to Canada( Reference Girard and Sercia 6 ). The integrity of these tools across higher-income or less-vulnerable populations is not known. As food insecurity is increasingly being reported in higher-income groups( Reference Tarasuk and Vogt 39 , Reference Gundersen and Garasky 40 ) there is a need to ensure that the measurement tools used to assess it are valid and reliable in these populations as well as validated across samples of the general population in developed countries. The focus on food insecurity as only a problem of the poor is evidenced by the studies found in the present review, but needs challenging in light of this emerging new evidence.

The findings of the present review provide insight into short, multi-item tools that policy makers and practitioners alike may consider in the face of limited resources that may restrict the use of the more comprehensive FSSM or its shorter iterations. However, they should be cautioned that these instruments may also underestimate the true prevalence of food insecurity( Reference Nolan, Rikard-Bell and Mohsin 37 ). To the authors’ knowledge there is no evidence to suggest that instruments overestimate the true prevalence of food insecurity. All instruments, despite their limitations, were able to measure food insecurity to some degree, yet the focus was on individuals or households. No individual instrument was identified that measured community food insecurity. This may be due to the fact that multiple methods and instruments, including healthy food basket costs, food outlet mapping and community needs assessment, are recommended to fully understand community-level food insecurity( Reference Cohen 41 ). There remains a need to develop a valid and reliable instrument to measure all four dimensions of food insecurity at the household, individual and community levels. Alternatively, in the absence of a comprehensive instrument, other methods may be used to complement these ‘food access’ assessments, for example food outlet mapping to measure ‘availability’.

To our knowledge, the present systematic review is the first using multiple databases and PRISMA guidelines to assess a wide variety of tools, alternative to the FSSM tool, relevant to only developed countries. One limitation of the review was that studies not in English were excluded, potentially omitting food insecurity measurement tools that might have been relevant to the research question, especially in developed countries of South America whose food insecurity issues are significant, and these stories may have strengthened the findings. This may explain why there was a low representation of European countries and tools. However, the focus on developed countries ensured that food insecurity issues of developing countries did not complicate or confuse the findings. In addition, validation studies conducted prior to 1999 would not have been captured in the present review. Another key limitation to our review is that the search terms did not include ‘food availability’ or ‘food utilization’ per se. The heterogeneous nature of the included studies and the review question meant that combining results and forming a meta-analysis was not possible. Limiting to the review to published work only is a further limitation, potentially omitting new tools in development or those not yet tested. The findings of the present systematic review, in conjunction with previous work by Marques et al. (2014)( Reference Marques, Reichenheim and de Moraes 17 ) and Keenan et al. (2001)( Reference Keenan, Olson and Hersey 42 ), may be used to guide decisions by practitioners, researchers and policy makers regarding the measurement and monitoring of food insecurity.

Conclusion

The present systematic literature review aimed to identify and characterize potentially valid and reliable tools, in addition to the FSSM, for the measurement of food insecurity in developed countries and to discuss the underlying dimensions of food insecurity assessed by any tools identified. The findings may provide guidance to practitioners and policy makers in selecting tools to assess food insecurity in situations in which the USDA tool may not be appropriate for use. The review found eight additional tools, shown to have moderate to high internal consistency, and varying levels of validity, among a variety of population subgroups at risk of food insecurity. These tools only measured access to food. There is a need for a valid and reliable instrument to measure all four dimensions of food insecurity at both the household and individual level, as well as to consider accurate measurements of community food insecurity.

Acknowledgements

Financial support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: C.P., S.K. and R.M. conceptualized the study. S.A. completed the searches, abstract/title screening, data extraction and quality assessment, and drafted the manuscript. C.P. and S.K. duplicated abstract/title screening, quality assessment and data extraction, and assisted in drafting and revision of the manuscript. R.M. assisted in drafting and revision of the manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: Not applicable.