Urbanisation in Malaysia has provided new opportunities for Malaysians to eat out more frequently, driven by the expanding range of out-of-home food options(Reference Poulain, Laporte and Tibère1). In this context, eating out refers to the consumption of food prepared outside the home by various food vendors, such as in food courts, food stalls, Mamak stalls (Indian Muslim stalls), restaurants, western fast foods, food trucks and hawker stalls, including takeaway or delivery services for indoor, office or home consumption(2). According to the Malaysian Adult Nutrition Survey (MANS 2014), 70 % of the Malaysian population regularly eat out, a particularly prominent trend among those residing in Peninsular Malaysia and urban areas(3). In 2019, household expenditure on out-of-home foods among Malaysians increased to 11·2 % from 8·7 % in 2004/2005(4). Consuming out-of-home food during various mealtimes, especially breakfast, has become popular among consumers in countries such as Uganda(Reference Sseguya, Nicholas and Swann5) and Malaysia(Reference Salleh, Ganapathy and Ibrahim Wong6).

In light of these circumstances, it is imperative to analyse the growing trend of eating out from a nutritional standpoint, considering the mounting evidence linking consumption of out-of-home foods to issues such as excess body weight(Reference Strupat, Farfán and Moritz7), obesity(Reference Bezerra, Curioni and Sichieri8) and increased risk of non-communicable diseases(Reference Salleh, Ganapathy and Ibrahim Wong6). This alarming phenomenon is predominantly attributed to the high intake of fat, salt and calories in food(Reference Sseguya, Nicholas and Swann5,Reference Strupat, Farfán and Moritz7) . The connection between excessive dietary salt intake and hypertension(Reference Mente, O’Donnell and Rangarajan9–Reference Grillo, Salvi and Coruzzi11) has become increasingly apparent. The 2019 National Health and Morbidity Survey underscored the persistently high prevalence of hypertension among adults in Malaysia at 30 %(12). Malaysians consumed an average of 7·9 g of salt daily(13), exceeding the maximum recommended limit of 5 g/d by the WHO(14).

The recent National Strategy for Salt Reduction 2021–2025 steadfastly pursues the global target of achieving a 30 % reduction in salt or Na intake by 2025(15) within the population. Based on the 2015–2020 strategy(16), the current endeavour sets a long-term target of 6·0 g of daily salt intake(15) by 2025. A midterm evaluation(17) of the previous strategy revealed that salt levels of out-of-home foods have not been comprehensively monitored compared with packaged foods, although these foods are a common source of unhealthy food choices among Malaysians. As such, this outcome emerged as a notable barrier hindering salt reduction efforts in Malaysia, prompting the present strategy’s emphasis on monitoring the salt levels in such foods. Another study(Reference Sharkawi, Mohamed and Rezai18) on Malaysians who frequently eat out revealed that the unavailability of healthy out-of-home food options as a prominent barrier impeding their adoption of healthier dietary habits. This issue is exacerbated among the low-income group in Malaysia, who often resort to unhealthy diets and frequent eating out(Reference Azizan, Thangiah and Su19). In addition, a previous study(Reference Azizan, Majid and Nahar Mohamed20) demonstrated the feasibility of dietary modifications within this group, emphasising the significance of improving the out-of-home food landscape. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the perspectives, barriers and enablers of salt reduction within Malaysia’s out-of-home sectors, focusing on street food vendors, caterers and consumers. Accordingly, the findings of this study contributed essential insights for formulating an inclusive nutritional policy aimed at salt reduction within the out-of-home sector.

Methods

This qualitative study design was adopted from a previously published primary research protocol(Reference Brown, Shahar and You21). This protocol employed focus group discussions (FGD) and in-depth interviews (IDI). The study adhered to the guidelines outlined in the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research(Reference Tong, Sainsbury and Craig22) to ensure comprehensive reporting of qualitative research, encompassing all requisite details as specified for a qualitative study (see Appendix A).

Participant recruitment and sampling

This study’s participants encompassed street food vendors, caterers and consumers from all five regions of Malaysia: West, North, South, East Coast regions of West Malaysia and east Malaysia. Street food vendors are defined as those who operates ready-to-eat food stalls for at least 2 years or more. Caterers consisted of individuals affiliated with reputable associations, including the Indian Muslim Restaurants Association, Chef Association, franchised food vendors, wedding caterers and school canteen operators. Consumers recruited through various eateries were those who habitually consumed outside meals at least three times a week. Consumers adhering to a low-salt diet or those dealing with conditions such as renal failure, heart failure or hypertension were excluded from this study(Reference Brown, Shahar and You21).

Participants were recruited through on-field approaches, established contacts and networking. Besides that, a roster of potential participants was compiled using diverse sources, including website searches, the Federal Agricultural Marketing Authority, and the Malaysian Agriculture Research and Development Institute. Invitations were extended through emails and telephone calls. As much as fifty street food vendors, fifty caterers and fifty consumers were invited. Those who were interested were required to complete an online registration form, providing their name, affiliation within the stakeholder group and contact information. Subsequently, these individuals were contacted to arrange the scheduling of their respective FGD sessions. Based on the snowball sampling technique, participants were encouraged to invite others who shared interest and availability to participate in the FGD session on the designated date. Individual IDI sessions were arranged for those unable to attend the FGD session. Table 1 shows the distribution of participants across the three stakeholder groups based on FGD and IDI sessions and regions. The response rate for this study was 50 % for vendors (n 25), 50 % for caterers (n 25) and 152 % for consumers (n 76).

Table 1 Distribution of participants across stakeholder groups by FGD/IDI and regions

* Session conducted online.

Pilot study and instrument

The questionnaires utilised for the FGD and IDI were developed based on a combination of the social ecological model(Reference Story, Kaphingst and Robinson-O’brien23), with adaptations derived from the UK Medical Research Council Guidance on Evaluating Complex Intervention(Reference Craig, Diepe and Macintyre24) and the Theoretical Domains Framework(Reference Phillips, Marshall and Chaves25), as described in the study protocol(Reference Brown, Shahar and You21). A pilot study was conducted among five individual representatives from the targeted participant pool in the central region to validate the questionnaire. Subsequently, refinements were implemented to enhance questionnaire clarity and relevance. This study employed distinct sets of questionnaires for street food vendors and caterers and consumers (see Appendix B). Before commencing the first session of FGD and IDI sessions, all research team members (comprising seven females, two males) underwent comprehensive training, including simulated sessions. This training familiarised the team with their roles as interviewers or moderators, honing their probing skills for addressing specific points of interest, cultivating prompting technique and other appropriate skills.

Data collection

The data collection process spanned from March 2020 to May 2022. A total of twenty-two FGD and two IDI were conducted face-to-face and situated in comfortable meeting rooms. Meanwhile, four IDI were conducted online through Google Meet due to COVID-19 restrictions. Each session comprised the participant/s, a researcher as the moderator or interviewer, and additional researcher tasked as a note-taker. The note-taker’s role entailed transcribing noteworthy topics discussed during the session, aiding the subsequent data analysis process. Before the commencement of each session, the roles of moderator/interviewer and note-taker were clarified with the participants, accompanied by a brief overview of the study’s purpose. Participants were informed about the audio recording of the sessions. They were also given an information sheet and a consent form in Bahasa Malaysia and English language. Once the completed consent forms were returned, the sessions commenced. The face-to-face FGD and IDI sessions ranged from 1 hour to 2 hours, and these interactions were documented with a digital voice recorder. In contrast, online IDI sessions lasting between 45 min to 1 hour were recorded using Google Meet. At the conclusion of each session, socio-demographic data were collected.

Data management

The audio recordings of the IDI and FGD sessions were transcribed verbatim. Throughout the transcription process and subsequent data reporting, each participant was allocated a pseudonym comprising their stakeholder group affiliation, a coded number, geographical zone and gender. This practice was adopted to maintain the confidentiality of all participants involved in the study.

Data analysis

The transcripts underwent analysis using an inductive thematic approach facilitated by NVivo (version 12; QSR International, Doncaster). The transcripts were initially assigned open codes during the analysis process, which were subsequently refined and amalgamated to form conceptual codes and sub-codes. This iterative process involved two researchers collaborating to establish a consistent coding framework, which was then subject to discussion and consensus within the research team. Codes that had been refined and shared similar connotations were either grouped into sub-themes or retained as standalone concepts. The emerging themes were then developed and discussed by the research team. These themes, accompanied by their corresponding sub-themes, were subsequently categorised into perceptions, barriers or enablers. To provide the descriptive insights into the participants’ socio-demographic characteristics, they were analysed descriptively using Statistical Products and Service Solution (SPSS) (version 25; Inc.).

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of the participants

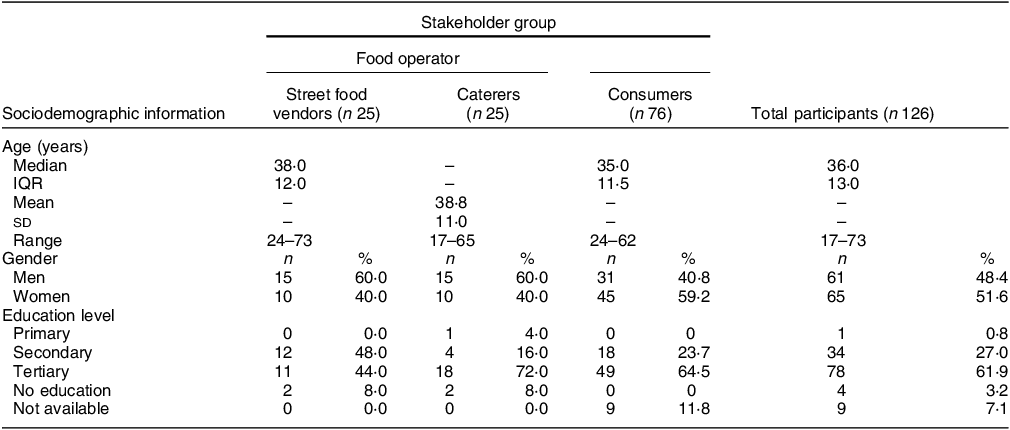

FGD and IDI were conducted across three distinct stakeholder groups: consumers of out-of-home foods (n 76), street food vendors (n 25) and caterers (n 25). Table 2 summarises the participants’ socio-demographic data in the three groups. Overall, the median age of participants in this study was 36 years. Predominantly, the participants were women (51·6 %) and had attained a tertiary level of education (61·9 %). The median and mean age were 38 and 39 years among street food vendors and caterers, respectively. Most vendors (60 %) and caterers (60 %) were men, and their educational qualifications varied between secondary (48·0 %) and tertiary (72·0 %) levels. On the other hand, consumers had an average age of approximately 35 years, with a higher representation of women (59·2 %). Most individuals within this category had achieved a tertiary education level (61·9 %).

Table 2 Sociodemographic data of the participants

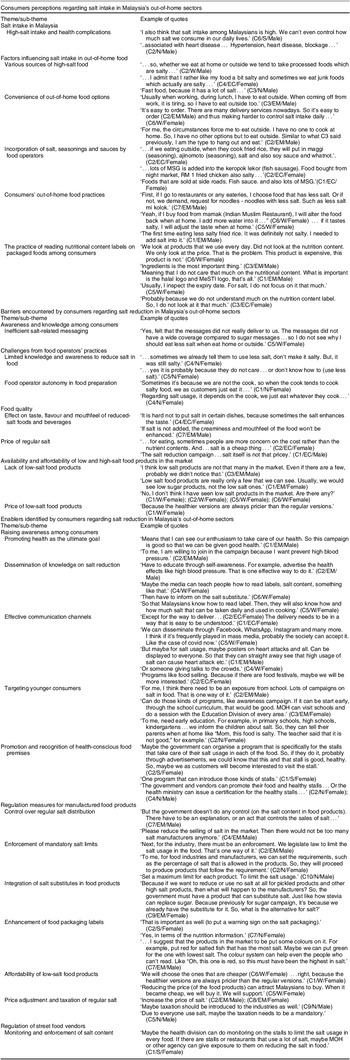

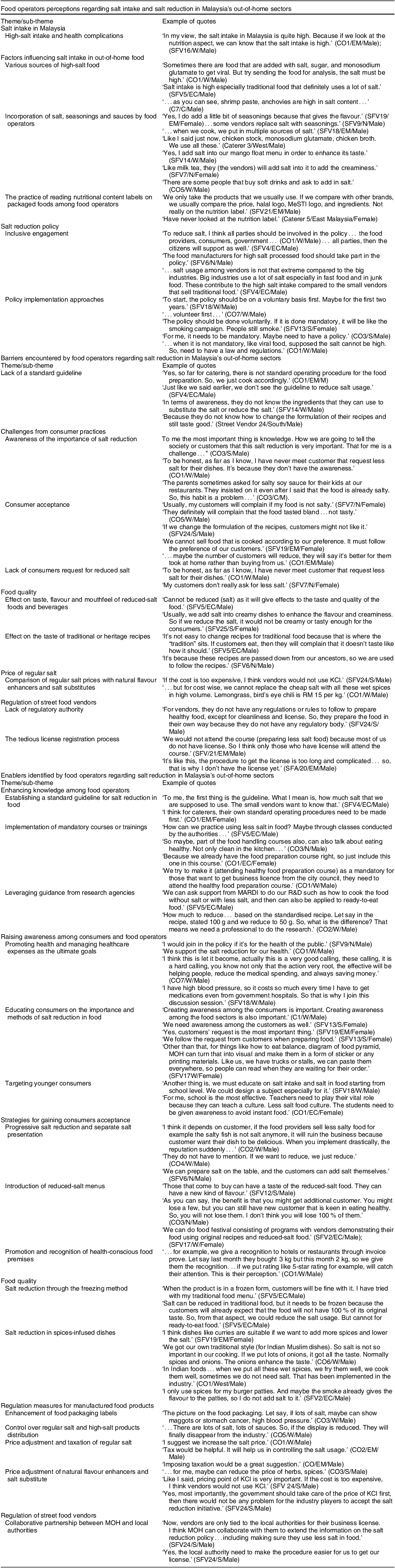

Table 3 presents an overview of themes and sub-themes related to the consumers’ perceptions, barriers faced and identified enablers concerning salt reduction within Malaysia’s out-of-home sectors. Further, Table 4 outlines the prevailing perceptions, encountered barriers and recognised enablers regarding salt reduction within Malaysia’s out-of-home sectors, specifically among the food operator group encompassing street food vendors and caterers.

Table 3 Perceptions, barriers and enablers regarding salt reduction in Malaysia’s out-of-home sectors identified by consumers

*C, Consumer; W, West; N, North; S, South; EC, East Coast; EM, East Malaysia.

Table 4 Perceptions, barriers and enablers regarding salt intake and salt reduction in Malaysia’s out-of-home sectors identified by food operators

*SFV, Street Food Vendor; CO, Catering Operator; W, West; N, North; S, South; EC, East Coast; EM, East Malaysia.

Consumers perceptions regarding salt intake in Malaysia’s out-of-home sectors

Salt intake in Malaysia

High-salt intake and health complications

The prevalent sentiment among consumers is the recognition of high-salt intake levels in Malaysia, which potentially contributes to health issues. Most consumers acknowledged the pervasive consumption of salt among Malaysians and the adverse health effects, such as hypertension and heart disease.

Factors influencing salt intake in out-of-home food

Various sources of high-salt food

Consumers identified diverse high-salt food sources, encompassing processed, junk and fast food. The accessibility and prevalence of these options contributed to the high-salt intake within Malaysia. Such foods were often consumed at out-of-home locations or brought home.

Convenience of out-of-home food options

Consumers leading busy lives, particularly those with work commitments, expressed that out-of-home food are convenient, especially for lunch and dinner. This sentiment was predominant among consumers from East Malaysia and the West region, who emphasised increasing access to out-of-home food options through food delivery services. Similarly, individuals living alone without a penchant for cooking appreciated the social aspects of eating out, such as the opportunity to meet and mingle with friends and family. Conversely, some consumers who usually cook at home found solace in occasionally eating out to escape the kitchen, also noting cost-effectiveness as a factor.

Incorporation of salt, seasonings and sauces by food operators

Some consumers mentioned that food operators often incorporate seasonings, salt and sauces into food sold in restaurants, roadside stalls and nighttime venues. This practice posed a challenge to managing salt intake when eating out.

Consumers’ out-of-home food practices

Consumers exhibited various behaviours when eating out that influenced their salt consumption habits. One consumer from East Malaysia highlighted the practice of selecting lower-Na options from the menu. In cases where such options were unavailable, they requested chefs to reduce the salt content in their meals. Similarly, some West Malaysian consumers took personal initiative by adjusting the saltiness of purchased foods once at home. However, among consumers from East Malaysia, there were instances where additional salt was added to purchase food if it is needed to be seasoned to their preference.

The practice of reading nutritional content labels on packaged foods among consumers

Majority of the consumers admitted that they did not have the habit of inspecting the nutritional content label when surveying food products in the market. Instead, they focused more on the price label, ingredients, halal certification, ‘Food Safety is the Responsibility of the Industry’ (MeSTI) label, and expiry date of the products. Some consumers expressed reluctance to scrutinise nutrition labels, citing challenges in comprehending the information provided.

Barriers encountered by consumers regarding salt reduction in Malaysia’s out-of-home sectors

Consumer awareness and knowledge

Inefficient salt-related messaging

In discussions about salt reduction campaigns and messages promoted by the Ministry of Health (MOH), many consumers expressed dissatisfaction with the delivery of these messages. Consumers found that salt reduction campaigns needed more visibility and impact than other messages related to sugar and energy intake. Therefore, the significance of reducing salt intake in both home-cooked meals and out-of-home dining failed to resonate with them.

Challenges from food operators’ practices

Limited knowledge and awareness to reduce salt in food

Some consumers noted that their requests for reduced salt in their meals often needed to be met, as the food still tasted overly salty. This circumstance may be due to limited awareness and knowledge among food operators regarding the importance and methods of salt reduction.

Food operator autonomy in food preparation

A recurring challenge, as expressed by most consumers, was their limited ability to regulate salt intake when consuming out-of-home food. This challenge arose from the fact that the final salt content of the dishes was solely determined by the cooks, influenced by their personal preferences and palate. Consequently, consumers needed more control over the amount of salt in their chosen dishes.

Food quality

Effect on taste, flavour and mouthfeel of reduced-salt foods and beverages

All consumers agreed that salt enhances the flavour and taste of food. As a result, reducing salt content was perceived as compromising the overall taste and appeal of dishes. Beyond flavour enhancement, salt was recognised for enriching the creamy texture of specific foods and beverages. Notably, creamy food and beverages containing coconut milk and dairy were identified as general types of food with salt-induced creaminess and enhanced enjoyment in consumption.

Price of regular salt

A consumer stated that due to the low price of regular salt, there might be little concern among out-of-home sectors about reducing its usage.

Availability and affordability of low- and high-salt food products in the market

Lack of low-salt food products

Many consumers noted the market’s limited presence of low-salt food products in the market. They further observed that the healthier variants of commonly available products mainly focus on reducing sugar content.

Price of low-salt food products

Most consumers agreed that low-salt products generally have a higher price tag than regular salt products. As a result, this discourages the consumers and even food operators from incorporating low-salt options.

Enablers identified by consumers regarding salt reduction in Malaysia’s out-of-home sectors

Raising awareness among consumers

Promoting health as the ultimate goal

Consumers exhibit a genuine interest in safeguarding their overall well-being. Therefore, focusing on health benefits as the campaign’s primary objective serves as a constant reminder to consumers about the advantages of reducing salt intake. This primary objective should be integrated into policies and campaigns.

Dissemination of knowledge on salt reduction

Consumers from East Malaysia suggested implementing a comprehensive awareness campaign to educate individuals about the vital significance of reducing salt in their diet. Educational messages should encompass instructive content, such as interpreting nutrition labels, understanding the role of salt substitutes, recognising diverse commercial salt varieties and their benefits and comprehending recommended salt allowances for consumption and cooking. In addition, outlining the health consequences of excessive salt consumption should be a focal point.

Effective communication channels

Consumers emphasised the importance of utilising appropriate communication channels to convey salt-related messages. One consumer noted that the messages would be more likely to be accepted if they were consistently promoted through social media. In addition to social media, visual aids, such as posters, banners and billboards, were also recommended by the participants. These visual mediums facilitate easy comprehension of the information. Verbal communication methods, including talks and presentations, were a means to reach larger audiences, particularly within community residences. Leveraging television and radio for advertisements between segments was also highlighted. Further, consumers were interested in participating in food festivals that feature reduced-salt food options.

Targeting younger consumers

Most consumers proposed initiating salt-related campaigns within educational settings, particularly schools, through collaboration with the MOH and Ministry of Education. This campaign approach involves all education levels, including kindergarten, primary and secondary schools. The participants emphasised that through such efforts, children can transmit the knowledge and awareness gained in schools to their families at home.

Promotion and recognition of health-conscious food premises

Some consumers proposed a government-led initiative highlighting food establishments specialising in low-salt food preparation. This programme would facilitate consumer identification of these establishments through advertisements or certifications.

Regulation measures for manufactured food products

Control over regular salt distribution

Consumers emphasised the necessity for governmental intervention to regulate the sales of regular salt within the market. Such regulation would result in a reduction in the number of salt manufacturers operating in the market.

Enforcement of mandatory salt limits

Consumers recommended the establishment of definitive salt content limits applicable to commercially produced food items. All food manufacturers must adhere to these limits, consequently steering the production of items within the prescribed salt limits. This measure would foster a market that predominantly offers low-salt food products.

Integration of salt substitutes in food products

Consumers recommended introducing alternatives to conventional salt for food manufacturers to facilitate the reduction of salt content, particularly in high-salt products. Encouraging the utilisation of salt substitutes would be essential in altering food product formulations, similar to how stevia is employed to replace sugar in sugar products.

Enhancement of food packaging labels

Consumers stressed the importance of refining the packaging of high-salt food products. The enhancement of food packaging labels includes warning labels of the adverse health conditions of excessive salt consumption and incorporating Na content details in the nutrition facts panel. To distinguish between low-, moderate- and high-salt food products, the consumers suggested implementing a traffic light labelling system to indicate the salt content levels using colours, aiding consumers in making informed choices.

Affordability of low-salt food products

Consumers indicated their willingness to purchase low-salt alternatives of commercially available food products if these options were reasonably priced. They acknowledged the prevailing trend where healthier alternatives tend to be priced higher than regular salt food products.

Price adjustment and taxation of regular salt

Based on input from consumers in the North, it was suggested that the price of regular salt should be increased along with the imposition of a salt tax. This dual approach discourages salt consumption within out-of-home sectors by making regular salt less economically viable.

Regulation of street food vendors

Monitoring and enforcement of salt content

A consumer suggested that MOH should monitor the salt usage and content on the menus of food stalls. This approach would involve transparently highlighting the efforts toward salt reduction in food offerings.

Food operators’ perceptions regarding salt intake and salt reduction in Malaysia’s out-of-home sectors

Salt intake in Malaysia

High-salt intake and health complications

Most caterers and food vendors agreed that Malaysians consumed much salt, with a collective awareness that excessive salt intake could lead to health complications, such as hypertension and heart disease.

Factors influencing salt intake in out-of-home food

Various sources of high-salt food

Food operators highlighted several factors contributing to Malaysians’ salt intake patterns. These factors include the prevalence of high-Na food sources, such as street food, fermented dishes, staple Malaysian dishes and traditional food. Street food operators tend to add salt and monosodium glutamate, rendering the food Na rich. Fermented delicacies, such as shrimp paste, budu (a condiment made from anchovies) and salted fish, were recognised as additional sources of high-salt content. Staple Malaysian dishes, such as asam pedas (a dish comprised of fish cooked in a sour and spicy gravy), fried noodles, noodle soup and other cultural staple foods, also tend to contain substantial salt levels.

Incorporation of salt, seasonings and sauces by food operators

Food vendors and caterers acknowledged that their practice of incorporating salt, seasonings and sauces into food and even beverages played a role in influencing consumers’ Na intake. Flavour enhancers such as monosodium glutamate, stock cubes and soya sauces were commonly employed to enhance flavour profiles. The practice extended to replacing salt with these seasonings and sauces or employing them in tandem. Some food vendors also disclosed that salt was commonly added to beverages, such as mango float and Teh Tarik, the Malaysian version of milk tea, to enhance texture and flavour. This practice was both vendor-initiated and customer-requested, as highlighted by a caterer based in the western region of Malaysia.

The practice of reading nutritional labels on packaged food among food operators

When surveying food products in the market, majority of the vendors and caterers admitted that they did not have the habit of inspecting the nutritional content label. Instead, they favoured purchasing familiar products. In cases where they did seek comparisons among brands, their focus lay primarily on price labels, ingredient lists, halal certification and compliance with ‘Food Safety is the Responsibility of the Industry’ (MeSTI) standards.

Salt reduction policy

Inclusive engagement

All vendors and caterers unanimously concurred on the necessity of a salt reduction policy, emphasising the inclusion of all relevant parties, including food manufacturers. Participants stressed that manufacturers of commercial food products should actively contribute to policy development, as their products significantly contribute to the high-salt intake among consumers. A food vendor highlighted that fast food and junk food manufacturers use more salt than food vendors. Therefore, the engagement of such food manufacturers is essential in shaping the out-of-home sector’s policy.

Policy implementation approaches

There were different opinions on the means of policy implementation. Most food vendors and caterers opined that initiating the policy voluntarily for a preliminary period before progressing to mandatory enforcement was a feasible approach. Nonetheless, some participants believed the policy should be wholly voluntary or exclusively mandatory. They cautioned that a mandatory approach might initially face resistance from some stakeholders. However, gradual adaptation would likely transpire over time. Further, participants noted that voluntary implementation might maintain the current status quo of salt intake.

Barriers encountered by food operators regarding salt reduction in Malaysia’s out-of-home sectors

Lack of a standard guideline

Most caterers and vendors highlighted the lack of guidelines for using less salt in food preparation as a significant hurdle. The absence of clear guidance makes it difficult for them to determine appropriate salt quantities and limits. Caterers and vendors also acknowledged limited knowledge regarding suitable salt substitution or reduction ingredients. In addition, they do not have the technical skills necessary to alter recipe formulations without compromising taste.

Challenges from consumer practices

Awareness of the importance of salt reduction

Most caterers pointed out that consumers were not aware and knowledgeable enough on the health importance of reducing salt in food; hence, consumers would find it hard to understand when the out-of-home sectors reduce the salt in their food. Further, they often received request from parents to add soya sauce into their kids’ meals although the food is already salty enough.

Consumer acceptance

Food operators are primarily concerned about consumer acceptance, given the nature of their business. Most customers complained whenever the food was bland or less salty than what they were accustomed to. Therefore, food operators must serve food according to customer preferences to avoid complaints and loss of customers.

Lack of consumers requests for reduced salt

In response to queries about customer requests for reduced salt, most vendors and caterers agreed that reducing salt content presents a challenge. This scenario is because most customers have never explicitly asked for their food to be less salty.

Food quality

Effect on taste, flavour and mouthfeel of reduced-salt foods and beverages

Most vendors and caterers agreed that salt reduction is not possible as that will negatively affect the taste, quality and creaminess of the foods and beverages.

Effect on the taste of traditional or heritage recipes

Some vendors expressed reservations about decreasing salt in traditional food or heritage recipes due to concerns that such adjustments might alter the taste and compromise such food’s customary and authentic flavours.

Price of regular salt

Comparison of regular salt prices with natural flavour enhancers and salt substitutes

Vendors and caterers highlighted that regular salt costs are significantly lower than salt substitutes such as KCl and natural flavour enhancers such as dry and fresh herbs and spices. This cost disparity encourages the prevalent use of regular salt in their culinary practices. Some vendors and caterers acknowledged that specific recipes maintain good flavours when herbs and spices are used to reduce salt. However, employing larger quantities of natural flavour enhancers incurs higher costs, as herbs and spices are more expensive than regular salt. On the other hand, since KCl is not widely available in the market, some vendors opined that it might command a higher price than regular salt. Thus, investing more in an expensive salt substitute that produces similar outcomes to regular salt might not be justified.

Regulation of street food vendors

Lack of regulatory authority

A prevailing sentiment among vendors is the need for a dedicated regulatory body, legal framework or guidelines monitoring their salt usage. They emphasised that their interactions with local authorities mainly revolve around food safety and licensing requirements, which they diligently adhere to while operating their stalls. However, no penalties or legal repercussions if their menu offerings exceed prescribed nutritional requirements.

The tedious license registration process

When queried about their willingness to participate in future training courses organised by MOH for preparing reduced-salt food, vendors from East Malaysia conveyed their reluctance. They cited the restrictive nature of the course, limited to registered vendors only, as the reason behind their decision. These vendors noted that many stalls are unregistered due to the complex and time-consuming procedure of obtaining a business license.

Enablers identified by food operators regarding salt reduction in Malaysia’s out-of-home sectors

Enhancing knowledge among food operators

Establishing a standard guideline for salt reduction in food

Caterers and vendors emphasised that the availability of a clear and comprehensive guideline for reducing salt in food would greatly assist them in minimising salt usage. They proposed implementing of educational programmes designed to teach them effective methods for reducing salt in food and providing these guidelines in a precise and accessible format.

Implementation of mandatory courses or training

Caterers operating in the North and East Coast regions suggested that educational and awareness programmes related to salt reduction could be integrated into the existing mandatory Food Handling Course, which is required for all food operators seeking business licenses. Currently, this course only focuses on the preparation of food that is safe and hygienic.

Leveraging guidance from research agencies

Vendors highlighted the need for comprehensive knowledge and guidance from research and development agencies such as the Malaysian Agricultural Research and Development Institute. They emphasised the importance of such guidance to enable them to prepare reduced-salt food offerings without compromising the taste and sensory appeal.

Raising awareness among consumers and food operators

Promoting health and managing healthcare expenses as the ultimate goals

The campaign holds significant appeal for the out-of-home sectors, driven by their concern for the nation’s health. Participants also recognised the potential for reduced medical costs as an outcome of the campaign. Thus, maintaining good health and reducing medical expenses could serve as strong incentives for active participation in the policy.

Educating consumers on the importance and methods of salt reduction in food

Creating consumer awareness serves as a crucial pillar to bolster the endeavours of vendors and caterers in reducing salt in their offerings. These operators believe that informed customers familiar with the salt reduction campaign would understand the significance and purpose behind their efforts. Vendors suggested that educating consumers to request for lower salt content would encourage their participation in the salt reduction campaign, as they are inclined to accommodate customer preferences. Further, displaying nutritional and health information from MOH on food trucks and stalls could effectively inform customers.

Targeting younger consumers

Vendors and caterers stated that awareness of salt intake and its presence in food should commence at the school level. Teachers are pivotal in cultivating a culture of reduced-salt consumption in schools. Initiating this awareness from a young age could shape healthier eating habits.

Strategies for gaining consumer acceptance

Progressive salt reduction and separate salt presentation

To address consumer acceptance and mitigate the risk of losing customers, caterers and vendors suggested a gradual reduction in salt content without the customers’ knowledge. In addition, they recommended presenting salt separately on tables, allowing customers to season dishes according to their preference.

Introduction of reduced-salt menus

Vendors and caterers advocate for the introduction of reduced-salt menus with regular offerings. This approach provides customers with more options and can attract new patrons. Although they might lose a few customers, it would be a partial loss. Moreover, organising low-salt food festivals gains traction as a captivating method to introduce consumers to reduced-salt food by vendors. Some caterers also suggested a ‘No Salt Day’ as part of the campaign, encouraging consumers and the out-of-home sectors to prepare and consume salt-free or low salt food.

Promotion and recognition of health-conscious food premises

A potential government initiative involves endorsing and promoting stalls, hotels or restaurants that align with the salt reduction campaign. Recognition could be granted through certifications, labelling as a ‘Healthy Choice Stall/Caterer,’ and implementing a star-rating system. According to vendors and caterers, customers tend to be drawn to establishments with star ratings similar to those employed by hotels. Therefore, the adoption of a star-rating approach by health-conscious stalls and caterers is likely to appeal to consumers. By amplifying promotion and recognition, vendors and caterers would be encouraged to believe that their reduced-salt offerings will remain appealing to customers.

Food quality

Salt reduction through the freezing method

Vendors highlighted the challenge of reducing salt content, particularly in traditional food, due to consumer expectations of maintaining familiar flavours. However, a potential solution is to freeze the traditional food. Vendors suggest that consumers may already perceived that frozen versions might exhibit a slightly altered taste compared with the non-frozen ready-to-eat variants. This difference in taste could result in fewer complaints regarding the flavour of the frozen version.

Salt reduction in spices-infused dishes

A strategic approach to reducing salt intake could begin with food rich in spices and herbs for flavour. Since these ingredients contribute substantially to the overall taste, minimal additional salt is necessary. This approach aligns with reducing salt while still delivering rich and appealing flavours.

Regulation measures for manufactured food products

Enhancement of food packaging labels

Vendors and caterers suggested enhancing the packaging of high-salt food products to facilitate the identification of such items when procuring ingredients. One possible enhancement involves incorporating warning graphic labels depicting potential health risks and consequences of excessive salt consumption.

Control over regular salt and high-salt products distribution

Caterers suggested implementing precise regulations to govern the market for salt and high-salt products such as sauces. Such measures could contribute to curbing the availability and consumption of high-salt options.

Price adjustment and taxation of regular salt

Caterers in the West region suggested increasing the price of regular salt, while those in East Malaysia advocated higher government-imposed taxes on salt. These financial adjustments could discourage vendors and caterers from excessive salt usage.

Price adjustment of natural flavour enhancers and salt substitute

Vendors and caterers suggested reducing the cost of natural flavour enhancers and salt substitutes. This price reduction could incentivise food industry professionals, including manufacturers, to incorporate these alternatives more extensively, ultimately reducing their reliance on conventional salt.

Regulation of street food vendors

Collaborative partnership between Ministry of Health and local authorities

In the context of street food vendors, a proactive collaboration between MOH and local authorities could procure positive outcomes. This collaboration would involve monitoring and regulating the salt content and its usage according to predefined nutritional standards. Vendors stated that local authorities are currently the primary entities responsible for regularly inspecting their stalls, although primarily for licensing purposes. Expanding this partnership to encompass vigilant monitoring of vendors’ salt usage aligns with the vendors’ suggestions and is considered a practical approach.

Discussion

Salt reduction initiatives targeting the global out-of-home sector remain limited(Reference Brown, Shahar and You21). Currently, these initiatives across the globe encompass a range of strategies, including interventions in settings, food reformulation with food industry, consumer education interventions, front-of-pack labelling and taxation on high-salt foods(Reference Santos, Tekle and Rosewarne26). It is important to note that among these initiatives, only twenty-one out of seventy-four surveyed countries have focused on the formal out-of-home sector, which includes fast-food chains and restaurants, employing an approach involving intervention in these settings. Notably, these initiatives have yet to target the informal sector, specifically street food vendors. Nevertheless, several studies(Reference Michael, You and Shahar27), a case study-based framework(28) and an informative toolkit(29) have collectively provided insights into the existing challenges associated with salt reduction in this sector and enablers or suggestions to overcome them. In this qualitative study, the researchers identified specific barriers and enablers related to reducing salt content in foods within this sector, as perceived by Malaysian consumers and food operators. Although most of the research findings were similar to other similar studies reported in a comprehensive review from 2021(Reference Michael, You and Shahar27), this study also revealed novel barriers, such as the intricate and resource-intensive process of registering street food establishments, and the promising potential for salt reduction in dishes rich in spices and the application of the freezing method.

In the current study, consumers highlighted limited awareness and knowledge among food operators in reducing salt during cooking as a significant barrier to salt reduction. This observation supports the findings from studies conducted in the USA(Reference Gase, Kuo and Dunet30) and Korea(Reference Park and Lee31). Food operators in this study also expressed a similar sentiment, suggesting that this lack of awareness might stem from the absence of a standardised guideline for reference. Consequently, food operators might cautiously approach salt reduction due to concerns about its potential impact on food quality. This shared concern between operators and consumers underscores the sensitivity of salt reduction and its potential to affect both food quality and consumer satisfaction unfavorably. This reluctance to adjust salt levels in food has been identified in other countries. Chefs in the USA and the UK(Reference Murray, Hartwell and Feldman32) and retail food sectors in India(Reference Gupta, Mohan and Johnson33) have similarly acknowledged their reluctance to modify salt content. This sentiment stems from the fear that altering salt levels could compromise the overall quality of the food, ultimately leading to a decrease in consumer acceptance. Such findings highlight the intricate balance that must be struck when pursuing salt reduction initiatives without compromising the culinary experience and consumer satisfaction.

Addressing this challenge could involve equipping food operators with adequate knowledge and skills for effective salt reduction through several measures. These measures encompass customised guidelines, specialised courses and training and guidance from pertinent research agencies. Similar to findings in other studies(Reference Michael, You and Shahar27), teaching food operators emerges as a commonly recommended enabler. In Malaysia, MOH has developed guidelines(34–37) targeting the out-of-home sector to encourage healthier food preparation. However, these guidelines primarily focus on calories, fat and sugar, leaving a gap in practical guidance for reducing salt in cooking. Therefore, a comprehensive approach entails integrating practical directives to curtail salt usage into these guidelines in tandem with addressing other nutrients. Courses and training opportunities(38–Reference Seah, Van Dam and Tai40) for food operators in Malaysia are already in existence. Based on a case study-based framework for healthier out-of-home food(28), established programmes on food safety present a potential entry point for encouraging healthier food practices. Notably, the Food Handler Course, which mandates food safety training for all registered food operators in Malaysia, could serve as a pivotal platform. Expanding upon this foundation, the optional Healthy Catering Training(38), currently emphasising low-salt food preparation, can be extended to incorporate essential nutritional components. Moreover, research agencies hold the potential to explore innovative technologies, such as freezing methods, that preserve the palatability of reduced-salt food offerings.

Insights from food operators in the current study presented several strategies to secure consumers’ acceptance of salt reduction measures. Among these suggestions are gradual salt reduction, separate salt preparation, introducing reduced-salt menus and recognising establishments that prioritise healthy food options. Valuable lessons from the successful implementation of salt reduction initiatives in the UK emphasise that gradual reductions in salt content within packaged foods often go unnoticed by taste receptors. This approach has not resulted in reported sales losses, product substitutions or increased table-side salt usage(Reference Girgis, Neal and Prescott41–Reference He, Brinsden and MacGregor43). Adopting this strategy to prepare out-of-home foods could involve gradually incorporating alternative ingredients such as herbs and spices and salt substitutes(Reference Michael, You and Shahar27).

Further, food operators must be convinced that gradual salt reduction would not compromise consumer acceptance(29). Interestingly, Malaysian food operators suggested a distinct perspective of placing salt on tables for consumers to add themselves. This suggestion contrasts with enablers from countries such as Argentina and Uruguay, where salt shakers were removed from restaurant tables, requiring patrons to request salt consciously(44). Another potential strategy to gain consumer acceptance lies in introducing reduced-salt menus. According to Michael et al.(Reference Michael, You and Shahar27), the lack of menu and food variety can impede salt reduction in the out-of-home sector in the USA(Reference Gase, Kuo and Dunet30), UK(Reference Jaworowska, Blackham and Long45) and Korea(Reference Lee and Park46), especially when many offerings are high in salt content. Therefore, creating menus designed to offer reduced-salt options could be a strategic approach to catering to consumer preferences while simultaneously promoting healthier choices.

Food operators and consumers opined that recognising healthy food establishments could significantly enhance consumer acceptance of salt reduction efforts. This recognition could manifest through certifications, labels denoting ‘healthy choice stall/caterer’ or the implementation of a star-rating system. A pertinent example of a salt reduction initiative involving labelling is the adoption of endorsement logos for Na content displayed on packaged foods. Three countries have adopted the Health Star Rating as a rating system. Meanwhile, nineteen countries, including the Netherlands and Malaysia, have integrated the Healthier Choice Logo to highlight low Na content across different brands(Reference Santos, Tekle and Rosewarne26). Given the recommendation for a star-rating system by food operators, the Health Star Rating system from Australia and New Zealand could serve as a viable model adaptable to Malaysia’s out-of-home food sector. Concurrently, MOH has established various endorsement logos and labels voluntarily granted to food operators adhering to specified nutritional standards. For example, the BeSS certification(37) is a recognition conferred upon establishments that meet criteria encompassing food safety and nutrition labelling (i.e. healthy eating poster displays, calorie tagging and the provision of plain water). Therefore, the BeSS certification could integrate salt content requirements as an initial step towards helping consumers identify health-conscious food premises as this recognition is already mandatory within government sectors, but remains voluntary in other settings. In addition, the MyChoice logo functions as an endorsement specifically for healthier menus served at respective food outlets(47). This approach continues the Healthier Choice Logo program, which initially endorsed nutritious packaged food across different brands. By leveraging these existing frameworks, Malaysia’s out-of-home food industry can promote healthier choices and facilitate consumer decision-making while advancing salt reduction goals.

Lack of awareness among consumers emerged as another barrier among food operators in reducing salt content. These operators noted that consumers’ limited awareness regarding the health benefits associated with reduced-salt consumption contributed to the prevailing trend of patrons not requesting lower salt levels in their meals. On the other hand, consumers stated that the degree of saltiness in their dishes rested solely in the hands of the cooks and chefs. Despite voicing requests for reduced-salt content, they often found their meals excessively salty. This disparity in perspectives between the two groups may be linked to their distinct backgrounds, potentially contributing to the seemingly inconsistent barriers identified.

Nevertheless, this disparity highlights the significance of developing strategies to increase awareness among consumers and food operators. Consumers emphasised that the dissemination of salt-related messages remained limited. While numerous educational resources featuring context-specific salt-related information have been formulated and assessed for Malaysia, a midterm evaluation(17) revealed a low public outreach and engagement. This shortfall might be attributed to inadequate federal-level mechanisms for direct communication with the public, coupled with limited opportunities and incentives at the state level to disseminate such information proactively. In addition, compared with the broader landscape of global salt reduction initiatives(Reference Santos, Tekle and Rosewarne26), fewer countries have implemented consumer education measures in 2019 than in 2014. This decline may be due to consumer education efforts’ resource-intensive and time-consuming nature(Reference Webster, Pillay and Suku48,Reference Trieu, Webster and Jan49) . Nevertheless, based on the current findings, it is evident that consumer education remains an essential component alongside other approaches for effective salt reduction(Reference Hyseni, Elliot-Green and Lloyd-Williams50–Reference Regan, Kent and Raats52). It is imperative to develop comprehensive strategies that enhance the reach and impact of these crucial messages to ensure broader outreach of salt-related messages to the public and food operators.

Challenges faced by consumers and food operators encompassed the cost and limited availability of low-salt packaged food products, the price of regular salt, natural flavour enhancers and salt substitutes. These challenges underscore the fundamental issue that food operators’ prevalent and affordable ingredients often lean towards high-salt options, while alternatives or low-salt ingredients are expensive. Notably, although commendable, Malaysia’s successful reformulation of fifty-three high-salt processed food products by 2018 had a limited impact on the population’s’ overall salt intake. This circumstance was because these reformulated foods were NS(17). In contrast, the UK’s effective salt reduction strategy encompassed reformulating commonly consumed items, such as bread, dairy, meat and convenience food, which generated successful outcomes. A pivotal barrier in the Malaysian context was the delayed implementation of Na labelling regulations, which hindered meaningful engagement between food manufacturers and reformulation efforts. However, as of 2022, mandatory Na labelling has implemented after a grace period, allowing food manufacturers to update their product labels. After reformulation, it is imperative to ensure that the prices of reformulated products are accessible to a wide range of consumers, accompanied by strategic nutrition labelling. This initiative can be realised by incorporating warning graphic labels and traffic light labelling, enabling the out-of-home sector to distinguish between low- and high-salt food products. Affordable pricing is essential to incentivise the adoption of low-salt products(Reference Seah, Van Dam and Tai40). The application of warning labels on front-of-pack labelling has proven effective in countries such as Chile, while eleven countries, including the UK, have implemented traffic light labelling. Accordingly, the efficacy of these enforcement measures in influencing population-wide salt intake should be vigilantly monitored, offering insights for ongoing improvement.

Consumer groups have advocated implementing mandatory salt limits for salt reduction in food. This strategic approach encourages the production of processed food items that boast reduced-salt content. Notably, fifty-seven countries have already established salt limits or targets across food products such as bread, processed meats and cheeses. However, most countries have adopted a voluntary framework for implementation(Reference Santos, Tekle and Rosewarne26), including the UK. Hence, the researchers propose an amendment to the current Food Act 1983 to encompass salt targets across various products. This simultaneous adjustment must be balanced with an unwavering commitment to food safety, reassuring manufacturers that reformulating their products will not compromise this vital aspect(Reference Harun, Shahar and You53).

Consumers have expressed interest in the utilisation of salt substitutes by food manufacturers. However, it is crucial to acknowledge that certain salt substitutes, such as KCl, have demonstrated a propensity to impart a bitter taste. This aspect poses a challenge in their complete substitution for regular NaCl, commonly known as table salt(Reference Zinno, Guantario and Perozzi54). Alternatively, natural flavour enhancers such as herbs and spices in reduced-salt food can evoke hedonic satisfaction similar to unreduced salt offerings(Reference Dougkas, Vannereux and Giboreau55). Therefore, advocating for integrating these natural flavour enhancers represents a promising approach for manufacturers and out-of-home food operators. Dishes rich in spices, like curries and offerings from Mamak restaurants, could be selected as trial samples for salt reduction initiatives. Notably, food operators have observed that these dishes inherently require less salt. Utilising them as test cases could offer valuable insights into effective salt reduction strategies within the out-of-home food sector.

Addressing affordability in salt reduction efforts encompasses reducing the cost of low-salt food products and natural flavour enhancers to incentivise their usage within the out-of-home sector(Reference Seah, Van Dam and Tai40) In addition, it includes potential interventions such as raising the price of regular salt and imposing a tax on salt. No existing salt reduction initiatives have systematically considered the price aspect for regular salt, low-salt food products or natural flavour enhancers. However, countries like Saint Vincent and Grenadines have implemented a 15 % value-added tax on salt(Reference Santos, Tekle and Rosewarne26). Meanwhile, other countries like Fiji, Hungary, Mexico, Tonga and Thailand have introduced taxes on high-salt products. Thus, this study proposes the implementation of taxes on regular and high-salt products within the Malaysian context. However, such strategies necessitate comprehensive evaluation and analysis.

Based on the Salt Reduction Toolkit(29), the WHO acknowledged the complexity of reducing salt intake within the informal out-of-home sector, particularly street food vendors, as many entities operate without registration or regulation. This challenge aligns with the perspectives shared by the vendors in the current study and a study involving local vendors in India(Reference Gupta, Mohan and Johnson33). In Malaysia, street vendors are only accountable to local authorities for stall registration. As part of this process, vendors must complete a Food Handling Course to ensure safe food practices, a prerequisite for registration. Further, local authorities occasionally monitor registered stalls to ensure adherence to food safety standards. However, a notable obstacle arises from the perception among vendors that the registration procedure is tedious. This perception has subsequently resulted in many vendors remaining unregistered, thereby escaping periodic supervision by the authorities.

The crux of addressing the salt reduction challenge within the informal out-of-home sector lies in the empowerment of local authorities. As highlighted in the WHO Salt Reduction Toolkit(29), local authorities play a pivotal role in implementing effective strategies for salt reduction in food. This approach involves integrating nutritional considerations into the vendor registration process and establishing mechanisms for ongoing monitoring alongside food safety protocols. Despite the existing focus on food safety policies and programs in Southeast Asia, including Malaysia, it is paramount to extend this scope to include salt reduction initiatives(28). For instance, vendors in Kolkata are monitored for food safety using a screening tool. As a progressive step towards promoting healthier out-of-home food options, these screening tools could be extended to encompass nutritional factors, such as weekly salt consumption. This expansion would identify vendors requiring additional training in food safety and essential nutrition. However, local authorities must establish simplified procedures for registering and licensing all vendors. This crucial step will facilitate salt content monitoring but also the vendors’ participation in future initiatives. Further, including nutrition components within the mandatory Food Handling Course, which presently centers on food safety, represents a logical progression to equip vendors with comprehensive knowledge of healthier food practices.

The active participation of food providers in the out-of-home sectors and consumers has been fundamental in enabling this study to gain diverse insights. Based on these insights, a comprehensive framework (see Fig. 1) has been devised, outlining practical strategies for salt reduction in the out-of-home food sector. This framework highlights the collaborative efforts required from consumers, the out-of-home food sector and other relevant stakeholders to foster a conducive environment for consumers to manage their salt intake when eating out. However, it is essential to acknowledge that the researchers’ presence could have influenced the input provided by participants during the sessions. Moreover, the subsequent data analysis and interpretations are inherently subject to the researchers’ skills and potential personal biases(Reference Anderson56). As such, transparency in methodology and an open recognition of potential limitations remain integral to ensuring the validity and reliability of the findings and proposed framework.

Fig. 1 Recommended strategies to assist consumers and the out-of-home sectors towards the salt reduction policy

Conclusion

In the present study, all the stakeholders agreed with the excessive salt consumption prevalent in Malaysia’s out-of-home sectors. Distinct barriers and enablers were identified within the consumer and food operator groups. Among the barriers impeding salt reduction in the out-of-home sector include concern over the undesirable effects on food quality and unsupportive practices among food operators, such as limited knowledge of salt reduction techniques and the absence of standardised guidelines. These barriers could be reduced through targeted educational initiatives for food operators. Proposed measures include the development of standardised guidelines, mandatory training courses, guidance from research agencies and strategic approaches aimed at consumer acceptance. Such strategies include gradual salt reduction, offering salt on tables for individual adjustment, introducing reduced-salt menus and promoting and acknowledging health-conscious food premises. Additional challenges include the scarcity of affordable low-salt food products and the competitive pricing of regular salt compared with natural flavour enhancers and salt substitutes. Therefore, it is essential to ensure the focus on the accessibility and affordability of healthier ingredients compared with regular salt and high-salt food products. The absence of strict enforcement mechanisms for the informal food sector poses another hurdle to successful salt reduction. Further, effective communication of salt-related messages to consumers and food operators requires enhancement, necessitating multifaceted interventions. A multifaceted intervention strategy involving out-of-home sectors and relevant stakeholders is recommended to develop a functional framework. Accordingly, the efficacy of such a framework can be gauged through outcome measurement, facilitating continual improvement.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to all participants involved in this study.

Financial support

Special appreciation to the Newton-Ungku Omar Fund (NN-2020-082) for financially support this research. This work is supported as part of the Newton Fund Impact Scheme by the Medical Research Council on behalf of UK Research and Innovation in the UK and by the Malaysia Industry-Government Group for High Technology (MiGHT) (grant number MR/V005847/1). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the MRC or MiGHT.

Conflict of interest

F.J.H. is an unpaid member of Action on Salt and World Action on Salt, Sugar and Health (WASSH). G.A.M. is the unpaid chairman of Blood Pressure UK, and chairman of Action on Salt and Chairman of WASSH. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Authorship

F.J.H., S.S., H.A.M., M.K.B. and G.A.M. have designed the study. S.S., Y.X.Y., V.M., H.A.M., Z.A.M., Y.C.C. and H.H. designed the instrument. Data collections were carried out by Z.N.Z.A., H.H., S.S., Z.H., V.M., Y.X.Y., Z.A.M., H.A.M. and Y.C.C. Data analyses were conducted by Z.N.Z.A. and Z.H., whilst the manuscript was prepared by Z.N.Z.A. All authors read the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscripts.

Ethics of human subject participation

This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Medical Research Ethics Committee (UKM PPI/111/8/JEP-2020-524), the Malaysian National Medical Research Ethics Committee (NMRR-20-1387-55481 (IIR)) and Queen Mary (University of London) Research Ethics Committee (QMERC2020/37). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S136898002300277X