Children in the USA are surrounded by large amounts of food and beverage marketing for calorically dense and nutrient-poor products(Reference Harris, Frazier and Romo-Palafox1–Reference Powell, Schermbeck and Chaloupka3). According to a report from the Federal Trade Commission, the food industry spent $US1·79 billion on food marketing to youth aged 2–17 in 2009, including nearly $US149 million specifically in schools(4). Exposure to unhealthy food marketing is associated with poor diet and risk of weight gain(Reference Andreyeva, Kelly and Harris5–Reference Kelly, Freeman and King7). In response to pressure from the public health community and increased attention by federal agencies(6), the Council of Better Business Bureaus established the Children’s Food and Beverage Advertising Initiative (CFBAI), a food industry self-regulatory and voluntary initiative that was fully implemented in 2007(8). As of 2019, eighteen food, beverage and restaurant companies belonged to the CFBAI and pledged to only advertise products that meet specific nutrition criteria to children under 12 years of age(8). Although the CFBAI represents a step in the right direction, public health experts have raised concerns about numerous limitations in company pledges, including that they only cover advertising to children up to the age of 11 and that the nutrition criteria for healthier dietary choices that can be advertised to children do not conform with expert recommendations(Reference Harris, Heard and Schwartz9,10) . In addition, although participating companies agree to not advertise branded foods or beverages to children in elementary schools, they exempt marketing via fundraising for foods to be consumed outside the school day; branded incentive programmes in schools; and food marketing in middle and high schools(Reference Harris and Fox11).

Recent research on food marketing in schools reveals that it takes on many forms, including logos on school equipment; fundraising using branded products; coupons from food companies to be given as rewards in the classroom; and branded educational materials(Reference Enright and Eskenazi12–Reference Kraak, Story and Wartella15). The many forms of marketing in schools pose challenges for monitoring and raising awareness as some examples (e.g. reward coupons) are not as obvious as sports scoreboards. Notably, marketing in schools remains prevalent nationwide; for example, 49·5 % of middle school students and 69·8 % of high school students attended a school with exclusive beverage contracts that aim to build brand recognition and loyalty(Reference Terry-McElrath, Turner and Sandoval13). Targeting youth in a setting where their parents are not able to serve as gatekeepers is particularly concerning and clearly violates the recommendation from the WHO that ‘settings where children gather’ should be free from unhealthy food marketing(16).

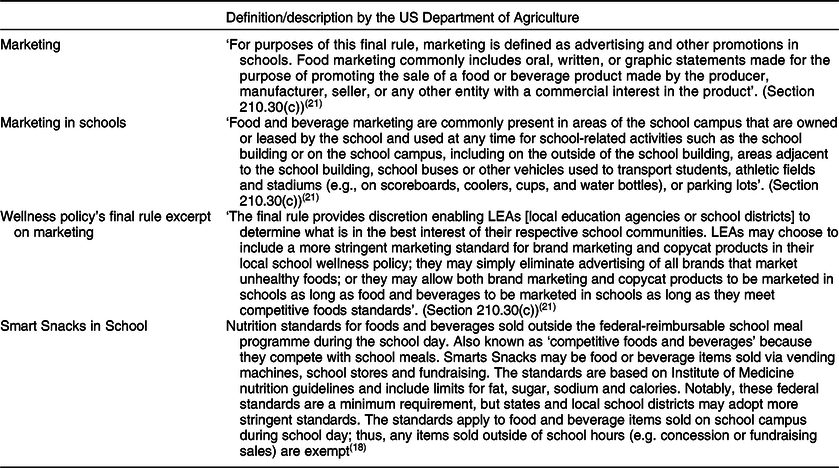

The 2010 Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act (HHFKA) created an opportunity to address unhealthy food marketing in schools. The HHFKA required the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) to update its regulations concerning local school wellness policies (hereafter, wellness policies)(17). Wellness policies have been required since 2006 for all districts participating in federal meal programmes. The 2016 final rule required districts to include policies to prohibit the marketing of food and beverages that do not meet the federal competitive food nutrition standards, known as ‘Smart Snacks in School’, on school property during the school day(18) (see Table 1 for definitions). Notably, the USDA stated that school districts could go beyond these minimum requirements and implement stronger policies. For example, schools could prohibit all brand marketing including ‘look-alike’ or ‘copycat’ Smart Snacks, which are reformulated products that meet Smart Snacks nutrition standards but maintain similar packaging and brand exposure(Reference Harris, Hyary and Schwartz19). In addition, school districts could restrict or limit food marketing beyond the school day and school property, such as fundraisers that occur off-campus or after school(18). As of the 2013–2014 school year, only 14 % of school districts nationwide adopted ‘strong’ food and beverage marketing policies within their local school wellness policies; ‘strong’ policy language includes those that ‘require’ action to address the policy, such as ‘must’ and ‘will’(Reference Piekarz-Porter, Schermbeck and Leider20). However, the study was conducted prior to the new federal regulations governing school food marketing. In a recently completed follow-up study by the senior author and her colleagues of a random sample of districts across twenty US states, the authors found that 50 % of the districts included definitive requirements restricting food marketing in schools as of school year 2017–2018(Reference Piekarz-Porter, Schermbeck and Leider21); thus, it is clear that districts are increasingly adding such provisions to their wellness policies.

Table 1 Definitions of marketing and related federal rules

Wellness policies are required to be developed by a committee comprising multiple stakeholders (e.g. parents, school food authorities, teachers, health professionals, the school board and administrators)(22). The final rule requires districts to establish wellness policy leadership from school districts to ensure compliance with the policy(22); ultimately, school superintendents are responsible for ensuring compliance with the federal law. In the USA, superintendents are the top administrator of the school district – sometimes called the ‘CEO of the school district’ – and oversee staffing, budgetary decisions and educational policies. Therefore, it is important to assess how superintendents understand and apply this new requirement to prohibit marketing of foods that do not meet federal nutrition standards. There are no studies, to our knowledge, that examined school district leaders’ perspectives on food marketing in schools. In response, the aim of the current qualitative study was to understand superintendents’ perspectives on food marketing in schools and food marketing provision in the wellness policy, as well as to identify any experiences with the implementation of food marketing policies.

Methods

Background

The National Wellness Policy Study is a mixed-methods study that examines the implementation of HHFKA 2010 and its related policies(23). The qualitative component, which included a series of stakeholder focus groups and interviews with food service directors, high school students, superintendents and parents of middle school students, focused on the experiences and perspectives related to the implementation of wellness policies and nutrition standards. Findings from other stakeholder studies are described elsewhere(Reference Asada, Hughes and Read24,Reference Asada, Hughes and Chriqui25) . The study was approved by the University of Illinois at Chicago Institutional Review Board (#2015-0720) and the University of Connecticut Institutional Review Board (H15-165).

Sampling and participants

The current study focuses on one component of the superintendent study, which included focus groups with superintendents and assistant superintendents (hereafter referred to as superintendents) who attended The School Superintendents Association (AASA) annual meeting in March 2017 in New Orleans, LA. AASA is a professional organisation that includes over 13 000 superintendents, chief executive officers and senior school administrators(26). Eligible participants were superintendents registered for AASA’s annual meeting, employed at any level of public K–12 school district and English-speaking. We sent e-mail invitations to participants who had registered for the AASA meeting requesting their attendance to one of six focus group sessions. Participants who responded were assigned to a focus group based on their school district characteristics (e.g. majority free and reduced price meal eligibility, school district size), in an attempt to create ‘homogenous’ groups to facilitate discussions(Reference Krueger and Casey27). Focus group superintendents were invited to participate in individual follow-up telephone interviews following the conference; those who agreed were contacted to schedule an interview time.

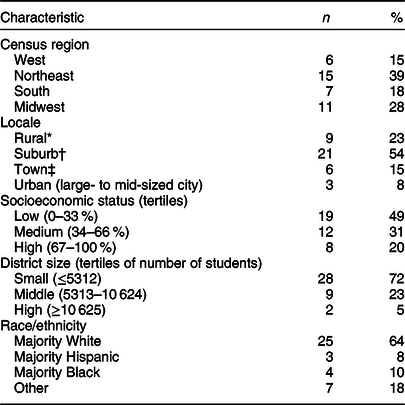

Superintendents (n 39) from all four US Census regions attended the focus groups, with a majority employed in suburban school districts (54 %), in small school districts (72 %), and in school districts with a majority of White students (64 %). Fourteen of the thirty-nine focus group superintendents participated in follow-up telephone interviews. Table 2 lists the characteristics of the school districts where the superintendents worked.

Table 2 Characteristics of superintendents’ school districts (K–12)

* The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) classification for rural includes rural-fringe, rural-distant and rural-remote, which range from ‘Census-defined rural territories that are less than or equal to 5 miles from an urbanized area (fringe) to 25 miles from an urbanized area (remote)’.

† NCES classification for suburb includes suburban-large, suburban-midsize and suburban-small, which range from ‘territory outside a principal city and inside an urbanized area with population of 250,000 or more (large) to a population less than 100,000 (small)’.

‡ NCES classification for town includes town-fringe, town-distant and town-remote, which range from ‘territory inside an urban cluster that is less than or equal to 10 miles from an urbanized area (fringe) to more than 35 miles from an urban cluster’.

Instruments and data collection

We could not obtain instruments previously used with superintendents; thus, we developed a focus group guide based on the theoretical framework and study questions; the guide was revised based on the feedback from USDA officials and pilot testing with two superintendents in order to refine the flow and appropriate terminology of questions. The guide asked questions broadly about superintendents’ awareness of wellness policies, oversight and evaluation, technical assistance and resources, perceived benefits and barriers, and food and beverage marketing policies (see online supplementary material). The follow-up interview guide was developed when focus group analysis was underway to reflect additional topics that emerged and further explore specific experiences with implementation. Focus groups lasted approximately 60 min; follow-up interviews lasted 40–60 min; both were conducted by trained qualitative researchers as moderators and room assistants. Participants completed a brief survey that included questions about demographics and awareness and engagement with their district’s wellness policy activities such as implementation and reporting. Superintendents were sent a $US50 gift card following the focus groups.

Data coding and analysis

Focus groups and interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed and uploaded into Atlas.ti Qualitative Data Analysis Software v8 for team-coding. An a priori coding guide was developed, based on study questions, and iteratively revised throughout weekly team-coding meetings(Reference Bernard, Wutich and Ryan28). Three analysts met to discuss discrepancies in coding, revisions to code meanings and emergent themes. Memos were used to document progress, study decisions and themes(Reference Bernard, Wutich and Ryan28). Matrices of themes for focus groups and follow-up groups were compared with document theme trends and new themes from follow-ups. Atlas.ti v8 exploratory functions were used to facilitate the team’s iterative analysis and to deepen analysis inquiries(Reference Friese29).

Results

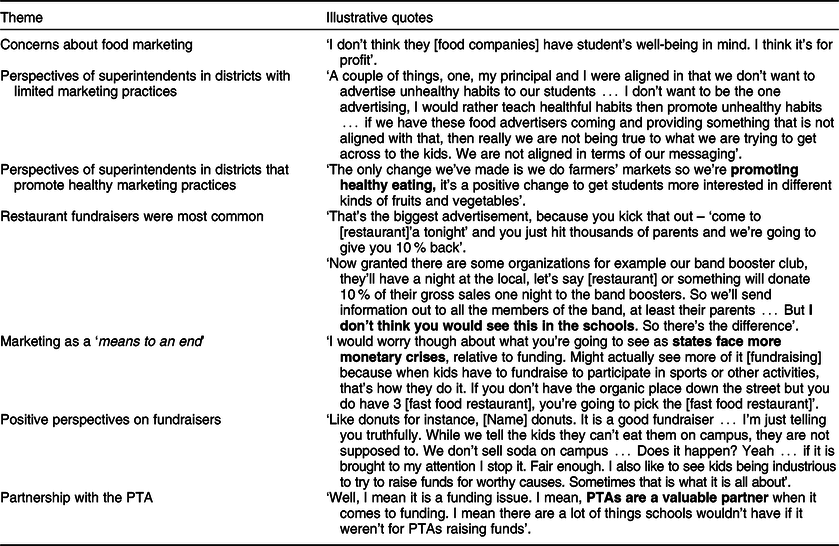

The wellness policy’s final rule required that school districts comply with the addition of a food and beverage marketing provision by 30 June 2017; our focus groups were conducted only 3 months before this deadline. As such, most participants were not aware of this requirement and most reported they did not have a marketing policy as a provision; only a few participants reported they had adopted a marketing policy and were able to recall their specific policy. Yet, despite limited awareness of the specific policy, most superintendents reported strong negative perceptions about food marketing on campus, reporting that food marketing benefited food companies at the cost of children’s health. However, actual food marketing practices varied widely. The following themes describe these findings; additional illustrative quotes are listed in Table 3.

Table 3 Illustrative quotes

Superintendents expressed concerns about food and beverage marketing in schools; however, actual policies and practices in their respective districts varied

The majority of superintendents agreed that food and beverage marketing allowed companies to target students as consumers of their products. Such practices were reported to have potentially harmful impacts due to the poor nutritional quality of marketed foods. Marketing was described as ‘insidious and evil’ by one superintendent and a practice that ‘must be combatted’.

Because they’re getting a foothold in the school. If you want to make a lot of money, you get yourself in with kids, with parents, and it’s junk food.

Despite common concerns about marketing, superintendents reported a wide range of food and beverage marketing policies in their respective districts. For example, some reported that they do not allow any type of marketing regardless of the type of items, which they reported to be easier to enforce compared with making exceptions.

Say we allow [candy company] to come in and put all their flyers out to market themselves, I also have to then let a group that I might not be in favor of come in and market. So a religious group or an anti-political group or a far-right or far-left group. If I let one in, I really can’t not let everyone else in. A zero tolerance policy to say, we don’t let anyone in.

Others focused on only allowing marketing for healthier food and beverages, or attempted to only allow items consistent with other wellness messages.

You know I don’t know that we have an explicit ban without our regulation on coordinated school health, I’d have to look at that. But what we’ve tried to do is just say, ‘look what is consistent with the message we want to convey?’

Specifically in my district, we wouldn’t participate in any of those programs because the marketing component isn’t attracting kids to food we want them to have … We do not hang up or promote something with [fast food restaurant].

Lastly, some superintendents noted no restrictions on food and beverage marketing, with minimal oversight of practices.

Restaurant fundraisers were most common and ‘implicitly endorsed’ restaurants

A common type of marketing that occurred on-(and off-)campus were fundraisers with branded products. Even superintendents in districts with stringent wellness policies noted that loopholes (e.g. sales after school hours) allowed for fundraising (and, as a result, marketing) of unhealthful foods. The most common example was restaurant fundraisers:

That’s what I was going to say. I see less of this [referring to scoreboards and box tops] now because we have policies in place to prevent it, with the exception of some sort of fundraising opportunity for the school itself. You know, come eat [restaurant]’s and 10 % of the proceeds go back to the school, so we do have that.

While some superintendents noted that these fundraisers focused on healthier restaurants, others noted that this was not always the case.

Our PTO [Parent Teacher Organization] has connected with [fast food restaurant] with the concept of putting something on one of our banners outside the building … Their [fast food restaurant] argument, I would assume, is that there is a healthy option. I think the rare times I used to go there, there is some reality to it that there is a healthy option. But in that reality, we all know they’re selling a whole lot more French fries than they are bottles of water or fruit cups.

Some superintendents noted that promotions of such fundraising events were typically directed to parents through e-mail notifications and not to students, while others noted that such events would be promoted districtwide on school campuses.

Or these businesses like [restaurant] will have a night where whatever club they’re representing can get 10 % of kickback from the sales that go on that night. We don’t advertise that through the school, it generally gets advertised outside the school. Or if it is advertised, it’s really just advertised to adults but indirectly it’s going to impact kids. They’re gonna take their kids, if they have them, to the event.

Some superintendents acknowledged that restaurant fundraisers ‘implicitly endorse[d]’ unhealthy practices and raised very little in the way of funding for the school, while a few participants had more positive perspectives of fundraising, noting that it helped the business community.

The other thing that we have to do is we have to be very conscientious about the decision making we are engaging in at a leadership level, because it is too easy to say, ‘oh great PTO has got the [restaurant] fundraiser going’ … I guess we are all going to implicitly endorse that because we are going to run 1,000 copies and send them home in their Thursday folders so everyone can see [restaurant mascot] and look, ‘20 % of all sales are donated to school’. Yay! What is that on a meal, somebody tell me, is that 12¢? That is awesome. Your budget problems are solved [laugh].

Yeah. [restaurant] offers 50 % back so it’s very generous. The food is healthy. [Restaurant], the deal with them is that the owners are so generous to all the fundraisers that they buy meals for teachers and give so big with their hearts, that we kind of do it as a way to give back to them. I know that sounds weird, but we had almost $3,000 worth of sales in the drive thru for them last night, on a week night. It kind of gives back to them. We do make $500 … I would say it’s kind of a mutually beneficial situation.

‘Means to an end’

A handful of superintendents described tough decisions to allow food and beverage marketing as a ‘means to an end’ due to budgetary shortages or because it promoted a desired academic behaviour such as reading.

Obviously it is a marketing tool for [fast food restaurant], but you know what, I just believe if we can get kids to read, it is important that to me especially K–1, 2 and 3 if you can read, you can conquer the world. If you can’t read you are going to have a tougher time at it. Whatever we need to do to encourage children to read … so, yeah we are promoting [restaurant] pizzas, but yeah it is a means to an end for us that we are encouraging kids to read.

They tell us they want to give us something free if the kids read and we say no, we don’t want it because it’s helping you out and marketing your private business. Now if the state of Illinois doesn’t get a budget together for public education in the next several weeks, I might say I’ve got to raise some money right now. Maybe I sellout so I can open the school up.

The complex issue of parent group fundraising oversight

A majority of superintendents noted that parent–teacher associations/organisations (PTA/PTO) were commonly involved with restaurant fundraisers. Interestingly, while most superintendents reported a process to formally approve school-sponsored fundraising activities, often PTA/PTO were not required to adhere to such procedures since most fundraising occurred after school hours and parent groups are considered a separate entity from the school district. Superintendents acknowledged that this was a complex issue, as PTA/PTO provided valuable funding and, thus, were hesitant to make changes to such practices.

If it is a school fundraiser and the money is going to go to the school there is a process where they have to submit a fundraiser form that has to be approved. But if it is the PTA doing the fundraiser I do not believe that is the case … I’m not aware of a district level form that has to be completed and approved for a PTA fundraiser.

We try to stay away from anything that is for-profit. Now the PTAs, we do allow the PTAs to do that … [restaurant] night, they still do about 3 or 4 of them as a fundraiser. That’s the PTA, we’ll let them do it, but the school themselves, we won’t do it …The PTAs might go to [restaurant]. We have stayed away from having these companies come into the schools.

Discussion

Superintendents expressed concerns about student exposure to food marketing in schools, and acknowledged that food companies that want to work with schools are primarily motivated by the opportunity to expose students to their brands. Many noted the inconsistency between exposing students to marketing for unhealthy foods and their core value to support student health. Further, superintendents recognised that students are exposed to food marketing even when it is primarily directed to parents or occurs outside of school hours. Therefore, the finding that some superintendents hold negative attitudes about food marketing, yet continue to permit marketing-related practices in their school districts, points to the challenges they face restricting these practices.

The most significant challenge superintendents face in protecting students from exposure to marketing is limiting food-related fundraising. Superintendents recognised that schools are under pressure to find additional funds to support student activities, and some are willing to compromise by allowing food fundraisers in order to meet other needs. Some are hesitant to challenge parent organisations about food-related fundraising because they appreciate the benefits of active parent engagement. Relatedly, they recognise that because the federal wellness policy provisions do not apply to fundraisers that occur after school hours or off-campus(22), there is a loophole through which parent groups can conduct fundraising that would not otherwise be permitted. These findings suggest that it may be important for parents who are active in PTA/PTO groups to also participate in the wellness committee and become more familiar with the rationale for limiting student exposure to food marketing. If the parents who are making decisions about fundraising activities are more fully aware of the policies that limit fundraising with food and the reasons behind those policies, they may be more open to pursuing non-food fundraisers.

Superintendents frequently referenced their own state’s laws when explaining the practices in their districts, suggesting that they are aware of state legislation related to schools. As of the 2017–2018 school year, four states (CA, DC, VA, WV) required that food and beverage items marketed on school campus be consistent with Smart Snacks standards(Reference Chriqui, Stuart-Cassel and Piekarz-Porter30). States provide guidance and resources for developing relevant policy language and supporting optimal food marketing practices(31,32) . The benefit of state laws is that they eliminate the need for each individual district to navigate potentially controversial and divisive policy topics. If superintendents are having difficulty in enforcing the district policy to limit food marketing, they can leverage the state law in combination with the federal requirements to reinforce their position.

At the time of the current study, many of the superintendents were not aware of the final rule provision in the federal wellness policy on food marketing. This suggests that groups that provide technical assistance to schools at the local, state and federal levels may need to prioritise educating superintendents on this change. One mechanism could be through the triennial assessments that state agencies are required to conduct as part of their participation in federal meal programmes.(22) State agencies could develop protocols for nutrition programme auditors to assess the non-cafeteria elements in wellness policies. For example, the auditors could inquire about marketing in schools and, if the district appeared to be unaware of the federal policy, provide resources, such as those developed by the USDA, to explain the final rule provision(33). Other groups that could provide education are state boards of education, state associations of local boards of education, ASCD (Association for Curriculum and Development)(34) and AASA.(26)

Study limitations

Notable study limitations include the purposive sampling of superintendents. As a qualitative study, we intended to sample ‘information-rich’ participants who could describe their awareness and experiences with wellness policies, so the sample was not meant to be representative of US school superintendents. As noted, focus groups were conducted a few months after the required adoption and implementation of federal food marketing policies; thus, most of our participants were not yet aware of this policy. Further, the sample was limited to superintendents who received financial support from the district to travel to a conference in Louisiana; again, such participants may not be representative of a ‘typical’ superintendent. Future studies may consider the levels of awareness since time has passed to allow for broader communication of the law. In addition, it is possible that the focus group setting (compared with the individual interviews) may have lend itself to superintendents responding in ‘socially desirable’ ways about their districts’ policies and practices as they shared with their colleagues.

Finally, the study was limited to perspectives of superintendents; we did not collect and/or triangulate superintendent accounts with other implementation or outcomes data at the school district level. Encouragingly, there has been some improvement in the past decade in the amount of exposure to marketing that children face in schools, primarily due to changes in beverage vending in schools(Reference Terry-McElrath, Turner and Sandoval13), and as noted earlier, there has been a marked increase in district wellness policies imposing definitive restrictions on food marketing in schools as of school year 2017–2018, which is encouraging. Future research is needed to monitor changes in food marketing in schools as the final rule regulations are now implemented. It will also be important to assess whether the sociodemographic characteristics of the students are associated with continued food marketing(Reference Terry-McElrath, Turner and Sandoval13). Finally, it will be useful to identify best practices among state-level efforts to assess marketing as part of the triennial assessments.

Conclusion

The inclusion of food marketing in the USDA final rule is a victory for the public health community that has expressed concerns about students’ exposure to food marketing in schools(6,10) . Superintendents in the current study reported strong concerns about the health and wellbeing of their students and motivations to provide a safe and healthy environment for their children. However, these district leaders reflected on their challenges posed by limited budgets, prevalent fundraising practices and parent group-run initiatives that often were exempt from district policy. The marketing provision outlined in the final rule of school wellness policy provides an opportunity for parents and administrators to come together to ensure that the school environment remains free from commercial influences that contradict lessons about nutrition and health taught in the classroom and at home. State and local governments can also provide additional technical assistance around working with parent groups and fundraising alternatives to limit potential opportunities for unhealthy food marketing on campus.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank Kayla Jackson of AASA and the superintendents who took time out of their busy schedules to contribute to the current study. We would also like to thank Alejandro Hughes and Margaret Read for their assistance with data collection and analysis. Financial support: This project has been funded by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) (School Wellness Policy Cooperative Agreement No. USDA-FNS-OPS-SWP-15-IL-01). The contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the USDA, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products or organisations imply endorsement by the US government. Conflicts of interest: The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest regarding the current study, or the writing and publishing of this article. Authorship: Y.A. co-led data collection, analysis and manuscript writing; J.L.H. and S.M. provided critical revisions to the manuscript; M.S. co-led study design, execution and contributed to manuscript writing; J.F.C. led the study design and execution and provided critical revisions to the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript for submission. Ethics of human subject participation: The current study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving study participants were approved by the University of Illinois at Chicago and University of Connecticut Institutional Review Boards. Verbal informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980019004804