Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.

–George Santayana

Literature and philosophy both allow past idols to be resurrected with a frequency which would be truly distressing to a sober scientist.

–Morris Raphael Cohen

In the 1950s and 1960s, Eysenck made some claims about the effectiveness of psychotherapy (Eysenck, Reference Eysenck1952, Reference Eysenck and Eysenck1961, Reference Eysenck1966). Our collective memories of the specific claims made by Eysenck have diminished over time and we seem to be left with the simple conclusion that Eysenck claimed that psychotherapy was ineffective (Wampold, Reference Wampold2013; Wampold and Imel, Reference Wampold and Imel2015). Recently, Cuijpers et al. (Reference Cuijpers, Karyotaki, Reijnders and Ebert2018) summarised Eysenck's claims by noting, ‘He [Eysenck] suggested that psychotherapies are not effective in the treatment of mental disorders (Eysenck, Reference Eysenck1952)’ (p. 1). It is important to know whether psychotherapy is effective or not. However, to make any statement about Eysenck and his claims, one has to understand exactly what he claimed and the bases on which he made his claims. We begin by reviewing what Eysenck had to say about the effects of psychotherapy.

Based on a review of research available at that time, Eysenck indeed did conclude that psychotherapy was not effective:

A survey was made of reports on the improvement of neurotic patients after psychotherapy, and the results compared with the best available estimates of recovery without benefit of such therapy. The figures fail to support the hypothesis that psychotherapy facilitates recovery from neurotic disorder (emphasis added; Eysenck, Reference Eysenck1952, p. 323)

When untreated neurotic control groups are compared with the experimental groups of neurotic patients treated by means of psychotherapy, both groups recover to approximately the same extent (emphasis added, Eysenck, Reference Eysenck and Eysenck1961, p. 719).

To be clear about Eysenck's claims about the ineffectiveness of psychotherapy, he compared the effects of psychotherapy with those patients who did not receive any treatment.

It is important to note that Eysenck was not simply impugning the absolute effectiveness of psychotherapy, he was at the same time concluding that one form of psychotherapy was effective and that other therapies were unscientific and ineffective (viz., behaviour therapy; Eysenck, Reference Eysenck and Eysenck1961; see Wampold, Reference Wampold2013; Wampold and Imel, Reference Wampold and Imel2015).

Given the distinction among various psychotherapies, any examination of Eysenck's claims must consider what is and what is not psychotherapy. Eysenck was very careful to define psychotherapy:

(1) There is an interpersonal relationship of a prolonged kind between two or more people.

(2) One of the participants has had special experience and/or has received special training in the handling of human relationships.

(3) One or more of the participants have entered the relationship because of a felt dissatisfaction with their emotional and/or interpersonal adjustment.

(4) The methods used are of a psychological nature, i.e. involve such mechanisms as explanation, suggestion, persuasion and so forth.

(5) The procedure of the therapist is based upon some formal theory regarding mental disorder in general, and the specific disorder of the patient in particular.

(6) The aim of the process is the amelioration of the difficulties which cause the patient to seek the help of the therapist (Eysenck, Reference Eysenck and Eysenck1961, p. 698).

Eysenck’s definition of psychotherapy is in accord with most definitions of psychotherapy, which emphasize that an interpersonal relationship is at the heart of the endeavor (e.g. Wampold and Imel, Reference Wampold and Imel2015).

Eysenck's claims created controversy as well as angst, among mental health professionals as well as the public. There were articles rebutting Eysenck's conclusions and rejoinders, creating a contentious interchange (for a summary see Glass and Kliegl, Reference Glass and Kliegl1983; Wampold, Reference Wampold2013; Glass, Reference Glass2015; Wampold and Imel, Reference Wampold and Imel2015). The debate about Eysenck's claims led to a proliferation of randomised clinical trials examining both the absolute efficacy of psychotherapy (i.e. the effects of psychotherapy v. natural history) and the relative efficacy of various treatments (i.e. the relative effects of different therapies; Wampold, Reference Wampold2013; Wampold and Imel, Reference Wampold and Imel2015). In the late 1970s, Mary Lee Smith and Gene Glass (Smith and Glass, Reference Smith and Glass1977; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Glass and Miller1980) conducted a comprehensive meta-analysis of controlled studies of psychotherapy and found that psychotherapy was indeed effective, with a standardised mean difference (SMD) between treated and untreated patients of approximately 0.70, a relatively large effect. Of course, Eysenck disputed these results by suggesting that meta-analyses ignored problems with the primary studies, such as the heterogeneity of included studies (‘apples and oranges’ problem) (Eysenck, Reference Eysenck1978, Reference Eysenck1984, Reference Eysenck1995). However, several re-analyses of Smith and Glass and additional meta-analyses have established an SMD of approximately 0.70, although this varies somewhat depending on the problem being treated (see Wampold and Imel, Reference Wampold and Imel2015).

Recently, Cuijpers et al. (Reference Cuijpers, Karyotaki, Reijnders and Ebert2018) have addressed several of the problems mentioned by Eysenck (and others) by examining the effects of interventions for a particular disorder, namely depression, considering various factors that might bias the estimates. In their article, a reassessment of the effects of psychotherapy for adult depression, they claimed, much in the way that Eysenck did, that there is insufficient evidence to declare that psychotherapy is effective:

These results suggest that the effects of psychotherapy for depression are small, above the threshold that has been suggested as the minimal important difference in the treatment of depression, and Eysenck was probably wrong. However, this is still not certain because we could not adjust for all types of bias (p. 1)… [and] the possibility that psychotherapies do not have effects that are larger than spontaneous recovery cannot be excluded (p. 7).

In this article, we address Cuijpers et al.'s (Reference Cuijpers, Karyotaki, Reijnders and Ebert2018) claims and show that a different understanding of Eysenck's conjectures produces an estimate of effectiveness for psychotherapy for depression that closely approximates what has been found previously.

A re-analysis of Cuijpers et al. (2018)

The goal of Cuijpers et al. (Reference Cuijpers, Karyotaki, Reijnders and Ebert2018) was to revisit Eysenck's conclusion that psychotherapy was not effective by meta-analytically examining the corpus of studies comparing an intervention for adults with depression to a control group and correcting obtained effects for bias of various types. Of course, as meta-analytic methods improve, it is commendable to scrutinise prior conclusions in light of the best available methods.

Cuijpers et al. (Reference Cuijpers, Karyotaki, Reijnders and Ebert2018) examined 369 effects produced by studies that compared interventions for depression with a control group. The overall effect for these interventions was an SMD of 0.70 suggesting that Eysenck's conclusions were in fact incorrect Q.E.D. But Cuijpers et al. claimed that this estimate was biased and when the effects were corrected for these biases the ‘true’ effect is between 0.2 and 0.3, casting some doubts on whether Eysenck's conclusions were truly incorrect. However, Cuijpers et al.'s conclusions depend on several methodological decisions that need to be re-examined. In this article, we examine several of their decisions and then reanalyse their data with decisions that we contend are more in line with Eysenck's conjectures.

Choice of control group

The corpus of studies in Cuijpers et al. (Reference Cuijpers, Karyotaki, Reijnders and Ebert2018) included three types of control groups: waiting list (WL, k = 159), care-as-usual (CAU, k = 144), and ‘other control’ (k = 66).Footnote 1 Unfortunately no definition of these types of control groups was presented and no methods for making this determination were provided (e.g. coding procedures, interrater agreement, etc.). What is most important is that Cuijpers et al. considered WL controls as biased and excluded studies using WL when estimating the true effect of psychotherapy. This is a decision that results in a significant decrease in the estimates of psychotherapy effectiveness, and one which is questionable. We examine each of these types of control groups, noting the questions that each is able to address.

Waiting-list controls

WL controls contain patients who are told that during the treatment phase they will receive no treatment (NT) as part of the study but that after the treatment period, if they choose to, they will receive one of the experimental treatments. To be clear, no treatment is provided to the patients and this type of control group is thought to be a means to estimate the natural history of the disorder (Wampold et al., Reference Wampold, Minami, Tierney, Baskin and Bhati2005; Stegenga et al., Reference Stegenga, Kamphuis, King, Nazareth and Geerlings2012). If we consider that Eysenck was focusing on the effects of psychotherapy compared with recovery without psychotherapy, it would seem that WL is an appropriate control group as it compares the outcome of psychotherapy with an estimate of natural course of the disorder.

There may well be methodological problems with WL controls. WL patients may actually improve during the study period because they became remoralised by anticipation of being included in a state-of-the-art treatment, which might not be obtainable elsewhere, in 15 or so weeks (Frank and Frank, Reference Frank and Frank1991). There is evidence that patients improve from when they make an appointment to receive services and when they present for such services (Frank and Frank, Reference Frank and Frank1991). Indeed, WL patients in clinical trials for depression improve quite dramatically during the waiting period; the effect for patients on WL in randomised controlled trials for depression from beginning of the waiting period to the end of the waiting period is approximately 0.40 (Minami et al., Reference Minami, Wampold, Serlin, Kircher and Brown2007; see also Posternack and Miller, Reference Posternack and Miller2001). WL patients may improve as a function of being included in the trial and therefore the use of WL controls may underestimate the effects of psychotherapy.

On the other hand, patients might feel demoralised by not being selected to receive treatment immediately: ‘Nothing good ever happens to me. I can't even get selected to receive treatment now.’ This is the resentful demoralisation threat to validity (Shadish et al., Reference Shadish, Cook and Campbell2002). However, there is little evidence that patients on the WL in clinical trials suffer from resentful demoralisation. Of course, many patients in routine clinical care are placed on waiting lists until services are available. Ahola et al. (Reference Ahola, Joensuu, Knekt, Lindfors, Saarinen, Tolmunen, Valkonen-Korhonen, Jääskeläinen, Virtala, Tiihonen and Lehtonen2017) studied patients on waitlists and concluded, ‘scheduled waiting should be regarded as a preparatory treatment and not as an inert non-treatment control’ (p. 611).

Cuijpers et al. (Reference Cuijpers, Karyotaki, Reijnders and Ebert2018) chose to question WL as a control group and exclude studies that used WL controls to estimate the ‘true’ effects of psychotherapy:

Waiting list control groups may stimulate patients to do nothing about their problems because they will get a treatment after the waiting period. Recent meta-analyses suggest that waiting lists may be a nocebo, and artificially inflate the effect sizes of therapies (Furukawa et al., Reference Furukawa, Noma, Caldwell, Honyashiki, Shinohara, Imai, Chen, Hunot and Churchill2014) (emphasis added, p. 2).Footnote 2

To be clear, Cuijpers et al. (Reference Cuijpers, Karyotaki, Reijnders and Ebert2018) claim is that WL is inappropriate because it might induce patients not to seek help. That is, patients on WL are purported to avoid seeking therapy or any other type of external help. Consequently, according to this view, WL patients represent the population of depressed patients not receiving treatment, which is exactly the control that should be used to determine whether a treatment is superior to spontaneous recovery without treatment. The Eysenckian conjecture that psychotherapy is not more effective than NT would suggest that WL control is a suitable, if not the suitable, hypothesis-driven control group.

What is the best way to empirically determine whether WL is biased? Logically one could compare WL control patients with NT controls. But how would that work? First, NT controls are unethical as one cannot deny patients with mental disorder treatment and that is the reason WL controls are used in lieu of NT controls. Second, NT patients would most likely experience effects of being included in a trial but be denied any treatment at all. They might be discouraged and deteriorate as a result or they might seek alternate treatment and improve – who knows?

Cuijpers et al.'s (Reference Cuijpers, Karyotaki, Reijnders and Ebert2018) attribution of bias for WL controls rests on purported evidence that WL cause patients to deteriorate relative to NT patients. But how is that known given that it is unethical to deny treatment to patients with mental health disorders who are seeking treatment? The meta-analysis cited by Cuijpers et al. that claimed WL artefactually causes deterioration (viz., Furukawa et al., Reference Furukawa, Noma, Caldwell, Honyashiki, Shinohara, Imai, Chen, Hunot and Churchill2014) is a network meta-analysis that involved clinical trials of cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) against various controls in the treatment of depression. A closer look showed that this meta-analysis contained 13 comparisons (from only six separate trials) with NT controls. However, none of the studies using an NT control involved patients seeking treatment for depression. The patients in studies with NT controls were college students selected for study (not seeking help for depression) or community members identified through screening. Most, although not all, were mildly to moderately depressed and all were not seeking treatment for depression. It is well established that seeking relief for distress is a vital factor for response to placebo (Price et al., Reference Price, Finniss and Benedetti2008). Interventions in NT trials were more similar to prevention programs than treatment programs and many NT studies did not involve psychotherapy according to Eysenck's definition. Prevention programs and programs for those not seeking treatment typically are ineffective (Lilienfeld, Reference Lilienfeld2007; Wampold and Imel, Reference Wampold and Imel2015). Consequently, it is understandable that the effects of CBT v. NT would be rather small. In the NT study that contributed more than half of all participants in NT comparisons in the Furukawa et al. meta-analysis (viz., Dowrick et al., Reference Dowrick, Dunn, Ayuso-Mateos, Dalgard, Page, Lehtinen, Casey, Wilkinson, Vazquez-Barquero and Wilkinson2000), the difference of intervention v. NT was only SMD = 0.169, suggesting that the treatments employed were only marginally helpful for participants. Of course, in the framework of Furukawa et al.'s network meta-analysis, these small treatment effects contribute to the impression of more change for participants in NT than in WL.

On the other hand, the CBT v. WL in the Furukawa et al. (Reference Furukawa, Noma, Caldwell, Honyashiki, Shinohara, Imai, Chen, Hunot and Churchill2014) meta-analysis included studies of patients seeking treatment for depression and it is not surprising that there were larger effects in these studies. The conclusion that WL is a ‘nocebo’ is due to the fact that the CBT v. NT prevention studies showed smaller effects than the CBT v. WL treatment studies, despite that the studies in these two comparisons were markedly different. Making inferences about the relative effectiveness of treatments or control groups (here WL v. NT) from network meta-analyses in lieu of examining direct comparisons often leads to erroneous conclusions (see e.g. Del Re et al., Reference Del Re, Spielmans, Flückiger and Wampold2013; Jansen and Naci, Reference Jansen and Naci2013; Wampold and Serlin, Reference Wampold and Serlin2014; Wartolowska et al., Reference Wartolowska, Judge, Hopewell, Collins, Dean, Rombach, Brindley, Uehiro, Beard and Carr2014; Wampold et al., Reference Wampold, Flückiger, Del Re, Yulish, Frost, Pace, Goldberg, Miller, Baardseth, Laska and Hilsenroth2017), especially when, as in Furukawa et al., the consistency of indirect estimates with direct estimates cannot be assured (none of the trials directly compared NT and WL controls). Thus, the results of this meta-analysis do not provide persuasive evidence that WL is an inappropriate control. Moreover, Furukawa et al. reported that the difference between NT and WL was not significantly different when publication bias was considered.

Given the problematic nature of the Furukawa et al. (Reference Furukawa, Noma, Caldwell, Honyashiki, Shinohara, Imai, Chen, Hunot and Churchill2014) meta-analysis and other evidence, we contend that WL is indeed an appropriate control group to address Eysenck's conjecture that psychotherapy is not more effective than NT.

Care as usual

To estimate the ‘true’ effects of psychotherapy, Cuijpers et al. (Reference Cuijpers, Karyotaki, Reijnders and Ebert2018) included CAU as appropriate controls. CAU is an appropriate control group if one is estimating whether psychotherapy is more effective than the various mental health treatments being given in routine care. However, CAU typically contains a wide array of treatments (Spielmans et al., Reference Spielmans, Gatlin and McFall2010; Wampold et al., Reference Wampold, Budge, Laska, Del Re, Baardseth, Flückiger, Minami, Kivlighan and Gunn2011), which was noted by Cuijpers et al.: ‘[CAU] is problematic since (sic) this varies considerably across settings and health care systems, making comparisons very heterogeneous’ (p. 3). Eysenck was making a claim that psychotherapy was not more effective than NT, not that it was not more effective than the usual care patients were receiving, which might well be psychotherapy or other mental health services. Indeed in Cuijpers et al. CAU included credible treatments such as supportive psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy delivered by experienced therapists (Saloheimo et al., Reference Saloheimo, Markowitz, Saloheimo, Laitinen, Sundell, Huttunen, Aro, Mikkonen and Katila2016); combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy according to Dutch Depression Guidelines (Wiersma et al., Reference Wiersma, Van Schaik, Hoogendorn, Dekker, Van, Schoevers, Blom, Maas, Smit, McCullough, Beekman and Beekman2015), or antidepressant medication (Power and Freeman, Reference Power and Freeman2012). CAU is often nearly as effective as first-line psychotherapeutic treatments for several disorders, including borderline personality disorder, anxiety and depression (Wampold et al., Reference Wampold, Budge, Laska, Del Re, Baardseth, Flückiger, Minami, Kivlighan and Gunn2011; Cristea et al., Reference Cristea, Gentili, Cotet, Palomba, Barbui and Cuijpers2017). Comparisons of these relatively active treatments produce effects irrelevant to Eysenck's claims about the effectiveness of psychotherapy vis-à-vis NT.

Other control groups

Cuijpers et al. (Reference Cuijpers, Karyotaki, Reijnders and Ebert2018) included ‘other control groups’ when estimating the ‘true’ effect of psychotherapy. They did not define what ‘other controls’ were but we examined these studies and found that ‘other controls’ included pill placebos (e.g. Elkin et al., Reference Elkin, Shea, Watkins, Imber, Sotsky, Collins, Glass, Pilkonis, Leber, Docherty, Fiester and Parloff1989; Dimidjian et al., Reference Dimidjian, Hollon, Dobson, Schmaling, Kohlenberg, Addis, Gallop, McGlinchey, Markley, Gollan, Atkins, Dunner and Jacobson2006; Hegerl et al., Reference Hegerl, Hautzinger, Mergl, Kohnen, Schütze, Scheunemann, Altgaier, Coyne and Henkel2010), or ‘so called’ psychological placebos (e.g. Watt and Cappeliez, Reference Watt and Cappeliez2000; Spinelli and Endicott, Reference Spinelli and Endicott2003; Armento, Reference Armento2012; Losada et al., Reference Losada, Márquez-González, Romero-Moreno, Mausbach, López, Fernández-Fernández and Nogales-González2015). We know that pill placebo with clinical management is often quite effective, often as effective or nearly as effective as antidepressant medication, particularly for depression (Kirsch, Reference Kirsch2002, Reference Kirsch2009, Reference Kirsch2010; Kirsch et al., Reference Kirsch, Deacon, Huedo-Medina, Scoboria, Moore and Johnson2008). Furthermore, psychological placebos are often quite effective (Baskin et al., Reference Baskin, Tierney, Minami and Wampold2003; Smits and Hofmann, Reference Smits and Hofmann2009; Honyashiki et al., Reference Honyashiki, Furukawa, Noma, Tanaka, Chen, Ichikawa, Ono, Churchill, Hunot and Caldwell2014). In any event, the use of pill placebo and psychological placebos addresses questions about the relative efficacy of psychotherapy compared to some relatively active controls, but does not address Eysenck's claims about the effectiveness of psychotherapy in comparison with NT.

Definition of psychotherapy

Cuijpers et al. (Reference Cuijpers, Karyotaki, Reijnders and Ebert2018) made conclusions about psychotherapy, as evidenced by the subtitle of their article: ‘A reassessment of the effects of psychotherapy for adult depression.’ If one is to assess the effects of psychotherapy vis-à-vis the claims of Eysenck, then it is incumbent to include only studies of psychotherapy. However, Cuijpers et al. did not provide any description of inclusion and exclusion criteria for psychotherapy and many of the studies in Cuijpers et al. were clearly not psychotherapy. For example, in one study depressed patients were given a copy of a self-help book based on cognitive therapy and were ‘asked to read the book and to complete all the homework exercises in the book within 1 month’ (Floyd et al., Reference Floyd, Scogin, McKendree-Smith, Floyd and Rokke2004, p. 305). In a similar study (van Bastelaar et al., Reference van Bastelaar, Cuijpers, Pouwer, Riper and Snoek2011), patients with diabetes and elevated depression symptoms were given access to a website with ‘eight lessons’ (p. 51) on depression and diabetes. Lamers et al. (Reference Lamers, Jonkers, Bosma, Kempen, Meijer, Penninx, Knottnerus and van Eijk2010) investigated a ‘minimal psychological intervention’ for elderly depressed patients delivered by ‘four nurses with no specific mental health expertise’ (p. 219). In Cuijpers et al. (Reference Cuijpers, Karyotaki, Reijnders and Ebert2018) we counted at least 61 effects derived from interventions that did not meet common definitions of psychotherapy, including Eysenck’s (Reference Eysenck and Eysenck1961) definition, recreating the ‘apples and oranges’ problem about which Eysenck was concerned. At the very least, conclusions about psychotherapy are unjustified when interventions that are not psychotherapy are lumped with psychotherapeutic treatments.

Western v. non-Western studies

Cuijpers et al. (Reference Cuijpers, Karyotaki, Reijnders and Ebert2018) excluded non-Western studies (viz., those from Africa, Asia and Latin America) based on the finding that the effects of psychotherapy were greater in non-Western countries. Cuijpers et al. (Reference Cuijpers, Karyotaki, Reijnders and Ebert2018) did not define ‘Western’ in a transparent manner (Latin America is in the Western hemisphere and Chile and Argentina are typically classified as ‘Western’) and provided no hypothesis-driven or theoretical reason to exclude evidence from some countries. Excluding non-Western evidence created smaller effects. Our re-analyses suggested the Western/non-Western effect is at least partially due to outliers, which we omitted in our re-analysis (see below).

Risk of bias

Cuijpers et al. (Reference Cuijpers, Karyotaki, Reijnders and Ebert2018) further reduced the number of studies by excluding studies with ‘possible systematic errors … or deviations from the true or actual outcomes’ (p. 3). It seems to us, however, that this reduction was conducted in a manner that discards relevant research studies. Specifically, ‘four items of the Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool’ (p. 3) were used to define risk of bias and studies were excluded if any one of these four criteria were coded as negative or unclear.

Using only four of the six domains of the Cochrane risk of bias (RoB) tool, Cuijpers et al.'s (Reference Cuijpers, Karyotaki, Reijnders and Ebert2018) definition did not cover a number of methodological aspects that are especially relevant for psychotherapy, possibly leading to the inclusion of studies with important deficits and to the exclusion of studies with appropriate methodology. In short, Cuijpers et al. excluded the RoB domains ‘blinding of participants and personnel’ and ‘selective outcome reporting.’ Coding the first domain was considered ‘not possible’ (p. 4) in the included studies and coding the latter was feared to result in ‘very few trials … with low risk of bias’ (p. 4) – that is to say, all psychotherapy studies have significant risk of bias. Clearly, patients and therapists are always cognisant of the psychotherapy they are receiving (or not receiving) and therefore blinding is not possible. However, there is broad consensus in the Cochrane and the psychotherapy research communities that exactly because of this deviation from the ideal experiment it is important to pay attention to methodological dimensions capturing quality of care and expectations (e.g. treatment credibility, therapist allegiance and treatment integrity), which were ignored in Cuijpers et al.'s (Reference Cuijpers, Karyotaki, Reijnders and Ebert2018) study (see Baskin et al., Reference Baskin, Tierney, Minami and Wampold2003; Higgins and Green, Reference Higgins and Green2011; Laird et al., Reference Laird, Tanner-Smith, Russell, Hollon and Walker2017; Munder and Barth, Reference Munder and Barth2018).

One of the studies excluded by Cuijpers et al.'s (Reference Cuijpers, Karyotaki, Reijnders and Ebert2018) definition of risk of bias is the NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program (Elkin et al., Reference Elkin, Shea, Watkins, Imber, Sotsky, Collins, Glass, Pilkonis, Leber, Docherty, Fiester and Parloff1989), even though this was considered the most sophisticated and methodologically rigorous clinical trial of psychotherapy ever conducted. In contrast, Cuijpers et al. included other studies that have important methodological shortcomings, including those with few therapists (Milgrom et al., Reference Milgrom, Negri, Gemmill, McNeil and Martin2005, with two therapists, and Burns et al., Reference Burns, Banerjee, Morris, Woodward, Baldwin, Proctor, Tarrier, Pendleton, Sutherland and Andrew2007 with one therapist) and several that did not monitor or assess adherence (e.g. Burns et al., Reference Burns, Banerjee, Morris, Woodward, Baldwin, Proctor, Tarrier, Pendleton, Sutherland and Andrew2007). Allegiance, an important aspect in psychotherapy studies (Munder et al., Reference Munder, Gerger, Trelle and Barth2011; Munder et al., Reference Munder, Flückiger, Gerger, Wampold and Barth2012; Munder et al., Reference Munder, Brütsch, Leonhart, Gerger and Barth2013) was ignored even though many of the studies in this data set were conducted by advocates of one of the treatments.

There are other problems with the Cuijpers et al. RoB determination. There are major discrepancies between the number of studies assigned to each risk category reported in Table 1 and Appendix C of Cuijpers et al. (Reference Cuijpers, Karyotaki, Reijnders and Ebert2018). Also, no coding procedure or interrater agreement was reported. Given these problems in Cuijpers et al.'s RoB determination, we did not use their ratings in our analysis.

Our estimate of the effects of psychotherapy

Professor Cuijpers, upon our request, provided the effect size estimators as well as their standard errors for all 369 comparisons. First, we examined the three types of control groups separately using standard random-effects meta-analysis using the ‘metafor’ package of ‘R’ statistical software (Viechtbauer, Reference Viechtbauer2010). In each case, we omitted the outliers (13 WL, 2 CAU and 1 ‘other control’) based on thresholds determined by visual inspection of the effect size distribution for each type of control and omitted comparisons for which g > 2.00. Removing such outliers reduces the estimate of the effectiveness of psychotherapy, compared with other procedures, such as Winsorization (Tukey, Reference Tukey1962), in which data are adjusted for outliers rather than eliminated entirely. Then, we also adjusted the effects for publication bias using trim and fill R0-estimates within the ‘metafor’ package.

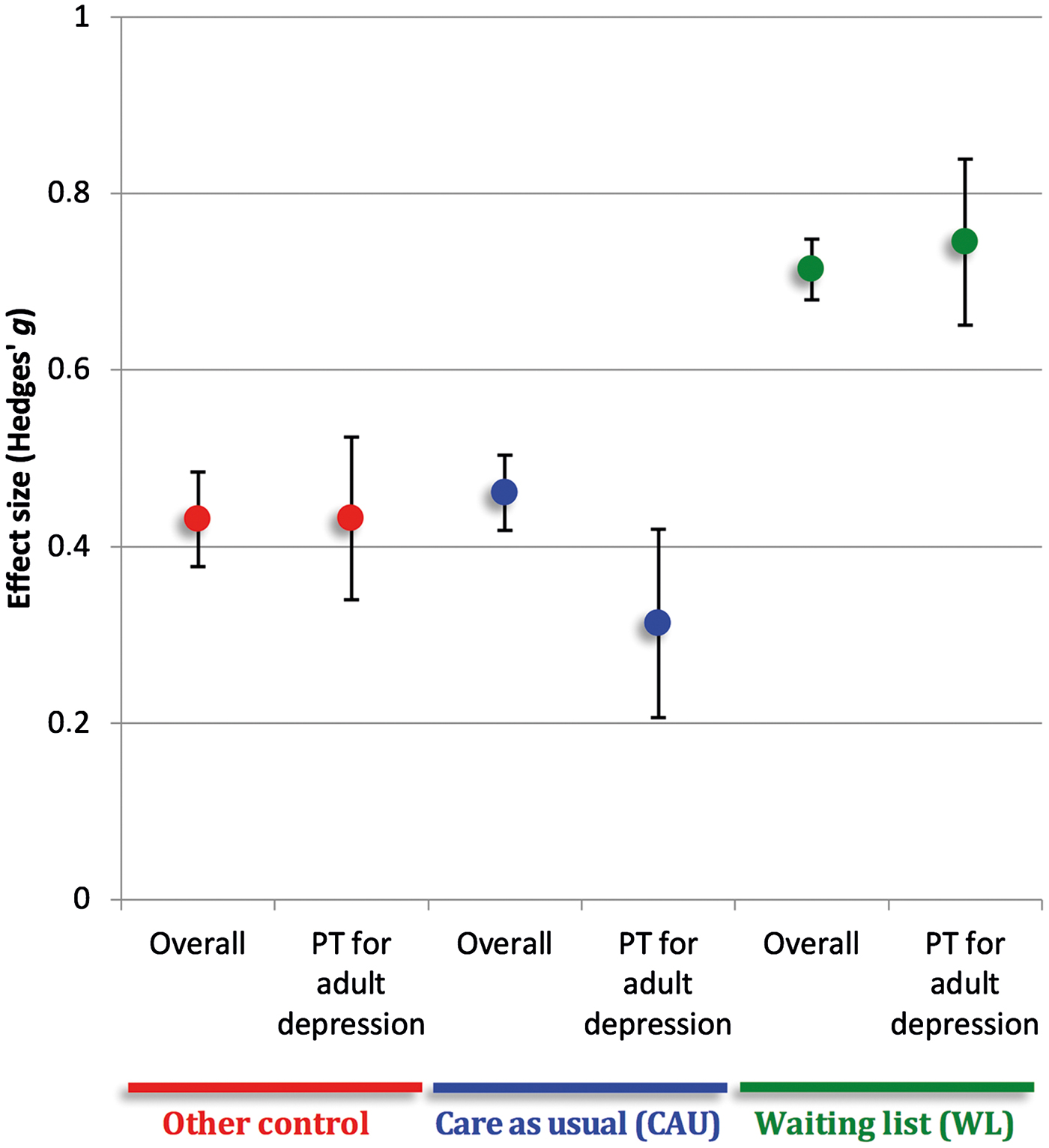

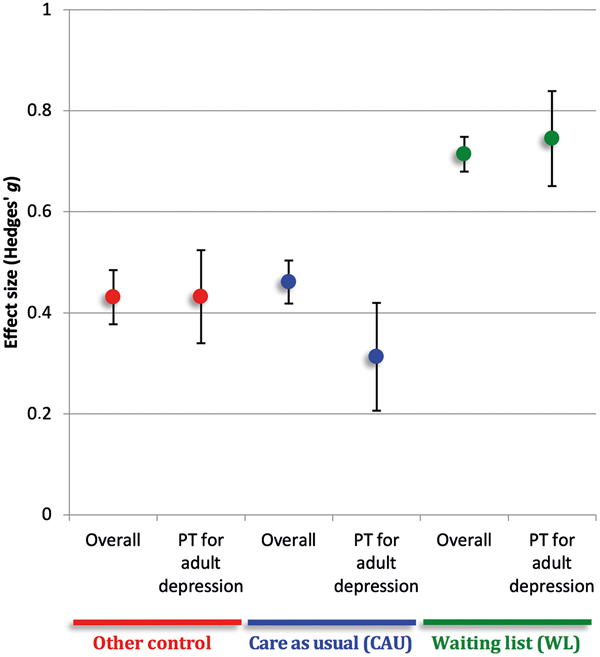

The results are shown in Fig. 1, for all comparisons and those that involved psychotherapy. As we have discussed here, the WL is the most appropriate control group for estimating the effects of psychotherapy compared with NT. As can be seen in Fig. 1, the effect of treatment v. WL is 0.71 (s.e. = 0.03), a statistically conservative estimate, given elimination of outliers and correcting for publication bias, and one which is similar to that determined by Smith and Glass (Reference Smith and Glass1977) and many others (see Wampold and Imel, Reference Wampold and Imel2015).

Fig. 1. Effect sizes for psychological interventions for depression. Error bars represent standard errors. PT = psychotherapy. Overall is based on all effect sizes without outliers and corrected for publication bias (k = 146 contrasts with WL, k = 142 contrasts with CAU, k = 65 contrasts with ‘other’ controls). PT for adult depression only includes (individual or group) psychotherapy for adults with a diagnosis of depression (k = 30 contrasts with WL, k = 29 contrasts with CAU, k = 12 contrasts with ‘other control’).

Because we wanted to restrict conclusions to psychotherapy, as defined by Eysenck, for the treatment of adult patients diagnosed with depression, we trimmed the data set accordingly. There were 270 comparisons that met definition of psychotherapy (either individual or group), of these 112 contained adults (excluding elderly, students, patients with general medical conditions or women with post-partum depression) and finally 71 comparisons that involved a diagnosis of depression. The effects for these 71 comparisons (30 WL, 29 CAU and 12 ‘other control’), after correcting for publication bias, are also presented in Fig. 1 (the standard errors are larger for the psychotherapy studies due to smaller sample sizes). The effect for psychotherapy v. WL in this set of comparisons was 0.75 (s.e. = 0.09), again confirming that psychotherapy is effective compared with NT, with a magnitude in the neighbourhood of what Smith and Glass (Reference Smith and Glass1977) found. Note, as well, that in this set of comparisons of treatments that were actually psychotherapy for adult patients diagnosed with depression, psychotherapy was significantly superior to CAU (Hedges' g = 0.31, s.e. = 0.11) and ‘other control’ (Hedges' g = 0.43, s.e. = 0.09).

We also tested the set of psychotherapy comparisons to see if there were differences among treatments. We used Cuijpers et al.'s (Reference Cuijpers, Karyotaki, Reijnders and Ebert2018) coding and found that there were no statistically significant differences among different types of psychotherapy for adult patients diagnosed with depression (adding type of treatment to a meta-regression model with the type of control did not significantly increase model fit, likelihood ratio test = 9.888, p = 0.195). This result is consistent with Cuijpers et al. and contradicts Eysenck's claims about the superiority of behavioural treatments.

There are some methodological limitations that may or may not impact the results of the present meta-analysis. First, face-to-face interventional studies are conducted in super-nested designs, randomisation procedures (as one of the key methods to handle risk of biases for internal validity) usually randomise patients to treatment conditions but therapists are neither randomly selected nor randomised to conditions, which may impact the generalisability of the study results to therapists that are not investigated under the study conditions (e.g. Wampold and Imel, Reference Wampold and Imel2015). Second, there were unsolved discrepancies between the main text and the Appendix of Cuijpers et al. (Reference Cuijpers, Karyotaki, Reijnders and Ebert2018) with regard to RoB criteria, which call into question the reliabilities of the RoB evaluations, further compounding the fact that rater procedures and rater agreement were not reported (see Hartling et al., Reference Hartling, Hamm, Milne, Vandermeer, Santaguida, Ansari, Tsertsvadze, Hempel, Shekelle and Dryden2012; Armijo-Olivo et al., Reference Armijo-Olivo, Ospina, da Costa, Egger, Saltaji, Fuentes and Cummings2014). Thus, quality of studies was not considered in our re-analysis. Third, although more statistical driven outlier definitions could have been applied (e.g. Viechtbauer and Cheung, Reference Viechtbauer and Cheung2010), we opted to exclude outliers based on visual inspection of effect size distribution. This had the advantage of being consistent with Cuijpers et al. who used the same definition of outliers. Fourth, we did not independently calculate effect sizes but used instead the effects provided by Cuijpers et al.

Conclusion

After removing outliers, correcting for publication bias, using WL control groups, and restricting analysis to psychotherapy studies, the results of our analyses reveal that psychotherapy for depression is demonstrably effective compared with NT. Indeed, the effect size for psychotherapy compared with natural history, as estimated using WL controls, is about the same size as is generally accepted (i.e. in the neighbourhood of 0.70).

The discrepancy between our results and Cuijpers et al. (Reference Cuijpers, Karyotaki, Reijnders and Ebert2018) is due in large part to what is considered an appropriate control group for determining the effectiveness of psychotherapy. Eysenck's claims were about the effectiveness of psychotherapy related to the natural history of the disorder. Determining natural history within the context of randomised clinical trials of psychotherapy is impossible but we have made a case that WL controls are the best possible solution for testing the particular conjecture put forth by Eysenck. Furthermore, dismissing WL conditions as biased is not supported by evidence. In any case, psychotherapy, as defined by Eysenck, is more effective than CAU, even when such care is quite credible, and is more effective than ‘other control’ as defined by Cuijpers et al.

Given these results, as well as a considerable corpus of evidence consistent with these results (Wampold and Imel, Reference Wampold and Imel2015), we argue that the field should accept the general conclusion that psychotherapy is an effective practice and give our attention to ways that psychotherapy could be improved.

Acknowledgement

None.

Financial support

None.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Target article

Is psychotherapy effective? A re-analysis of treatments for depression

Related commentaries (1)

Encompassing a global mental health perspective into psychotherapy research: a critique of approaches to measuring the efficacy of psychotherapy for depression