Introduction

The British government's internment of ‘enemy aliens’ during the Second World War, including Italians between the ages of 16 and 70 with less than 20 years’ residence in Britain, and the sinking of SS Arandora Star, 125 miles north-west of Ireland on 2 July 1940 by U-47 when deporting internees to Canada, have been discussed elsewhere (Colpi Reference Colpi, Cesarani and Kushner1993a; Sponza Reference Sponza2000, Reference Sponza and Dove2005; Pistol Reference Pistol2017), and are further addressed in this issue. The impact of the Arandora Star (AS) tragedy on the Italian community, especially at ‘pockets of affect’, defined as clusters of loss and emotion (Colpi Reference Colpi2020), the legacy of silence, and eventual recognition and commemoration have likewise been assessed (Chezzi Reference Chezzi2014; Giudici Reference Giudici and Gourievidis2014; Ugolini Reference Ugolini2015; Colpi Reference Colpi, Carr and Pistol2023). By employing a new paradigm, that of the deathscape, defined as a topography of death and the practices that surround it, including the meanings attributed to such spaces by the living (Maddrell and Sidaway Reference Maddrell and Sidaway2010), this paper progresses AS scholarship. Material remembrance in Scotland is recontextualised by investigating the spatially and culturally inflected accumulations that have located and shaped the deathscape, providing fresh insight.

The lack of materiality and its repercussion in the AS deathscape is reassessed within discussion of ambiguous loss and complications in bereavement and mourning. Disenfranchisements in grief (Doka Reference Doka1999), socio-religious practice (Colpi Reference Colpi1993b) and spatialities are woven into parallel discourse of emotional-affective memory (Maddrell Reference Maddrell2016). The connotation of absence pervades the text, reflecting the complexity and inconclusiveness of the historical event, its practicable aftermaths, and its resultant unresolved memory. Drawing on empirical research and primary sources, the previously neglected study of AS individual memorialisations, both private and ‘official’, is examined, revealing hitherto uncharted material dimensions and allowing analysis of both cultural practice and political aspects of the deathscape. I argue, on the one hand, the cultural, an unbinding of disenfranchisement through posthumous memorialisation, and on the other, the political, an obfuscation of AS deaths. Finally, the significance of individual leadership, Italian identity and commitment to AS heritage by memory activists is evaluated through the semiotics and physicality of the Italian Cloister Garden and AS Memorial in Glasgow as the material and cultural apex of the deathscape.

Materiality, mourning and memory

The most impactful aspect of the AS has always been the almost total absence of materiality surrounding the event and its legacy. In the first instance, lack of documentation featured. Not all families received official ‘missing presumed drowned’ notifications and death certificates were only issued through lengthy and costly legal routes. The fact that none of the 93 deaths of Italians resident in Scotland prewar,Footnote 1 and only four of eight identifiable bodies found on Scottish shores were registered, substantiates this point.Footnote 2

Losses at sea add a substantial layer of ambiguity to death, leaving no physical imprint, with no possibility of burial or later disinterment. Yet, with ‘hundreds of bodies … left there floating on the ocean’ (Balestracci Reference Balestracci2008, 314) near the scene of the sinking, their non-recovery by the rescuers became a recurring theme in the narrative of the greatest material absence. From a total of 707 Italians embarked (Pacitti this issue), 420 men were missing without trace. Research revises not only the number of Italian victims from the previously accepted 446 (Colpi Reference Colpi1991, 271–278) to a new total of 442, but also the number of recovered identified bodies. In 2008, Balestracci accounted for 13 bodies (Reference Balestracci2008, 350); a number that 15 years later had risen to 21 (Colpi Reference Colpi, Carr and Pistol2023, 61), with the latest research now counting 22 identified bodies. Along with an unknown number of unidentifiable bodies, these men were washed ashore at isolated and sometimes inaccessible locations along the Scottish (eight bodies), and Irish (14 bodies) coastlines.Footnote 3

With the tracing of relatives often protracted or unachieved – Enrico Muzio's family, for example, only learning of his burial on the Isle of Barra in 2004 (Balestracci Reference Balestracci2008, 332) – participation in the immediate procedures associated with death was not feasible or practicable. For potentially all the bereaved, the absence, or effective absence, of bodily physicality was not only traumatic but also prevented any ritual in death and mourning. Consequently, families were deprived of effective grief resolution achieved through these inherently transformative processes. Rituals deliver a route for publicly expressing strong emotions; ‘their repetitive and prescribed nature eases feelings of anxiety and impotence and provides structure and order at times of chaos and disorder’ (Romanoff and Terenzio Reference Romanoff and Terenzio1998, 698). Affirming the human dignity and relationship of the deceased to the community, fulfilling cultural and religious obligations and transmitting healing properties, are all central to ritualised mourning practice (Castle and Phillips Reference Castle and Phillips2003). Italians of the prewar generations in Scotland proclaimed themselves resolutely Catholic (Colpi Reference Colpi2015, 138), and can be considered attached to the practices and rituals operating within the Church's performative framework of death. These comprised administration of the last rites sacrament by a priest; laying-out of the body for family and friends to pay respect; funerals conducted by way of Requiem Mass; burial in Catholic cemeteries; high frequency graveside attendance (Goody and Poppi Reference Goody and Poppi1994, 150); and remembrance Masses on death anniversaries (Romanoff and Terenzio Reference Romanoff and Terenzio1998, 701–702). Absence of bodies in AS mourning prohibited these ritualised structures and the solace afforded by them. This prevented movement through normal mourning, shaping an inconclusive and ‘complicated grief’. The sudden, unexpected deaths and especially their perception as preventable by the bereaved, added to the complication (Rando Reference Rando1993, 5). Acute sadness, anger, guilt, blame and difficulty in accepting the deaths were prolonged, often escalating rather than abating (Shear Reference Shear2015), thus causing deep psychological challenge and lack of closure. As in Italy, due to missing bodies during the First World War ‘… mourners were never to be free of their pain, they were condemned to mourn endlessly, an eternal bereavement’ (Foot Reference Foot2009, 45). Indeed, in late 1990s Edinburgh, children of AS victims in their eighties were found to be almost frozen to ‘the moment of grief’ (Ugolini Reference Ugolini2015, 90).

Remnants of this emotional and social abyss amongst AS families can be detected amongst descendants even today, described by one victim's grandson as ‘an ever present absence’,Footnote 4 remarkably evocative of Avril Maddrell's relational ‘absence-presence’ syndrome whereby attachment to the deceased often fosters an ebbing and flowing sense of presence (Reference Maddrell2013). Presence of absence captures the tension between a past loss and its impact on the present, with traumatic past war experiences recognised as not ‘dead’ but ‘full of vitality’ that can ‘suddenly burst, or slowly seep, through any temporal and spatial imaginations’ (Mannergren Selimovic Reference Mannergren Selimovic, Otele, Gandolfo and Galai2021, 17). This type of absent-presence/present-absence subjectivity transmitted to and embodied by post-generations of Italians, mainly, but not exclusively, descendants of AS victims, has been partly responsible for the longevity of AS affective-emotional memory. The unresolved grief and not-knowingness of the past find resonance in the present through ‘carriers’ (Duncan Reference Duncan, Giuliani and Hodgson2022, 228–229), who strive to keep AS memory alive. Discussion returns in the final section to these ‘memory choreographers’ (Conway Reference Conway2010, 6), who by their lives’ actions perform as physical memorials to the missing.

In addition to the extreme trauma caused by ‘ambiguous loss’ (Boss and Ishii Reference Boss, Ishii and Cherry2015) and the complicated grief described above, the bereavement process was profoundly compromised by the enemy alien status of the victims’ families during the ensuing five years of war and the postwar period (Ugolini Reference Ugolini2015; Colpi Reference Colpi2020). Inability to acknowledge the deaths publicly and the absence of any institutional or host community support acted to increase personal debilitation and intensify social alienation. AS losses thus fit not only into definitions of complicated, but also, more significantly, ‘disenfranchised grief’ – sorrow that ‘is not, or cannot be, openly acknowledged, publicly mourned or socially supported’ due to society's unwritten rules of sanction in mourning (Doka Reference Doka1999, 37). This corresponds to Maddrell's idea of navigating life in emotionally unsafe spaces (Reference Maddrell2016); for enemy aliens we can problemitise this as society's rejection of the right to grieve. Legitimacy of grief sanction and how victims are remembered differently depending on who is responsible for memorisation (Butler Reference Butler2016), has meant that AS remembering, and later commemorative onus and impetus, resided almost entirely with bereaved families and the wider Italian community (Colpi Reference Colpi2020, 405).

A further, previously unacknowledged, form of marginalisation that frustrated grief resolution had its taproot in the religious prejudice towards Catholics in Scottish society (Devine Reference Devine2000). Yet, whilst intolerance of Catholics was undoubtedly potent in ‘unmooring’ the AS bereaved, a still more disabling form of disenfranchisement was paucity of support from the Catholic Church itself. Although individual Italian missionary priests later became important in both AS narrative formation and succour giving (Colpi Reference Colpi2020), the hegemony of the Presbyterian establishment, alongside Italian cultural dissonance within the predominantly Irish Church (Colpi Reference Colpi1993b), framed a disinclination on the part of the Catholic hierarchy to afford sanctuary for rehabilitation and a disassociation from any culturally ‘other’ outpourings of grief. Moreover, Italian priests were also interned and only one of three prewar Italian clerics remained to tend the community's spiritual and emotional needs.Footnote 5 In addition to this ministering void, an absence of any Italian clubs or associational spaces (Colpi Reference Colpi2015, 124–125; Petrocelli Reference Petrocelli2022, 228), and closure of the fasci as places of assembly for many, meant there were no sanctioned or institutional meeting venues where bereavement support groups could sustain the process of adaptive, ‘healthy’ grieving. Only through the private enactment of informal gatherings in ‘back shops’ or at each other's houses did a connective context arise to provide comfort for mourners.

In combination, trauma, lack of grief resolution and disenfranchisement in mourning for both individuals and the Italian collective, were responsible for the silence and oblivion that foreclosed not only release, but acknowledgement of the emotional burden. This in turn caused prolongation of AS memory and also created ‘a deep psychological need for monuments, commemorations, and memorial sites for the families of victims’ (Foot Reference Foot2009, 45). The ambiguity of the losses was exacerbated by absence of official information, which propagated an environment whereby families had to ‘construe their own ending to their traumatic story’ (Boss and Ishii Reference Boss, Ishii and Cherry2015, 274). A mythology grew and endured even after the silence had been ‘broken’ (Chezzi Reference Chezzi2014). The belief that not all ‘questions’ had been adequately answered persisted (Capella Reference Capella2015), perpetuating the memory of hurt and wrongdoing. The robustly constructed AS narrative (Colpi Reference Colpi2020), remains somewhat fossilised in time, conceivably incapable of realigning to incorporate new research and shades of more factually informed perspectives (Rumble this issue).

One long-term outcome of the material void is the not uncommon custom of collecting AS memorabilia from the ship's prewar cruises (Figure 1), offering an intimate trace of the deathscape in the domestic sphere. In this way, individuals continue, or create – those who ‘never knew my nonno/grandfather’ – their relationship with the lost family member, and at the same time connect to AS memory and its meaning. Hallam and Hockey (Reference Hallam and Hockey2001) stress the importance of tangible mnemonic artefacts for facilitating relations between the living and the dead while Miller and Parrott (Reference Miller and Parrott2009) consider gathering material things as part of a complex process of sorting, divestment and accumulation that helps generate relationships with loss. Acquisition of ship's models, souvenirs and insignia demonstrates material agency in AS remembering and also evokes Margaret Gibson's concept of ‘melancholy objects’. Such items not only materialise and signify the memory of loss but form ‘memorialized objects of mourning’ (Reference Gibson2004, 289). In post-generation AS not-forgetting, these objects represent an affective reminder that grief has never entirely dissipated; they manifest the residual trace of embedded sadness and longing. Their conjuring capacity of reverie and meditation has a ‘haunting effect’, invoking powerful mnemonic reconstruction of the sinking itself. A spiritual aspect can also be suggested, the tangible items acting as pseudo relics or ‘bridging’ communicators with the dead. Resonating with Joseph Sciorra's description of Italian American vernacular altars in New York (Reference Sciorra2010, 1), little domestic shrines with religious statues, votive candles and photographs of AS deceased, configured as private sites of mourning, were still evident in Italian homes in 1980s Edinburgh.

Figure 1. Arandora Star memorabilia and ‘melancholy objects’; photo John Sidoli

Geographies of deathscape

Despite the overwhelming material chasm in the AS deathscape, by introducing new empirical data on the archaeology and symbolism of individual Italian headstones in Scottish cemeteries, an examination of cultural traditions, memorialisation practices and their political implication is possible.

The period of AS victim burial, memorialisation of absent bodies, and of survivor burial began in August 1940 and continued until the 2010s, by which time the majority of the wartime generation had died.Footnote 6 John Mackenzie highlights what he terms ‘documents in stone’, discussing how deaths overseas were sometimes commemorated on family tombstones at home in Scotland ‘as though there was an imperative to bring family members together in carved memorialisation’ (Reference Mackenzie, Evans and McCarthy2020, 176). For AS victims a similar, albeit retrospective, symbolic homecoming or reunification praxis can be detected. Commonly, when burying another family member at a later date, most usually an AS widow, the previously unrecorded and unmarked missing victims were named on family headstones. Examples of this practice can be seen at the Catholic cemeteries of St Kentigern's, Glasgow and Mount Vernon, Edinburgh.Footnote 7 Grief surrounding the later death of a widow, for example, Vittoria Marre in 1979 (Figure 2), becomes overlaid with recursive, absence-presence mourning for the missing AS victim, bringing the memory to the fore and transporting the bereaved family back to the earlier trauma. These graves thereby become layered palimpsests of affective-emotion.

Figure 2. Arandora Star family headstones. Left: ‘Alessandro Pacitti, hero of the Arandora Star … died Glasgow 1st February 1991’; photo Gina Pacitti. Right: ‘Carlo Marre … lost at sea on the Arandora Star July 2nd 1940 aged 59 years’; photo Anthony Schiavo

The language of commemorative inscriptions can be read as operating at a number of key social and ideological levels. ‘On the one hand they [inscriptions] represent family life, affection, love, pride and loss, but on the other they also project the ideology of the age, the sense of rightness of the enterprise in which the deceased person had been involved’ (Mackenzie Reference Mackenzie, Evans and McCarthy2020, 179). By contrast, explicit occurrence of the words ‘Arandora Star’ carved on family headstones, as well as more general epitaphs such as ‘drowned’ or ‘lost at sea’ appear to evince feelings of wrongness in death. Such expression articulates the affective need to publicly name and mark the previously unmentionable historic event and death. The former disenfranchised grief is thus unbound and brought into sanctioned, ritualised mourning through the widow's death and these posthumous grave inscriptions.

Nor is it uncommon for AS survivors’ gravestones to mention the ship, as seen on the headstone of Alessandro ‘Russian’ Pacitti (Figure 2), who died in 1991 aged 83 in Glasgow (Colpi Reference Colpi2015, 69–73). This inscription indicates family pride by referencing the ‘cavaliere’ honour and nomination as ‘hero’ of the Arandora Star.Footnote 8 Furthermore, in the last 20 years or so, with later deaths and addition of further names to family tombstones, the practice of replacing the entire stone with reworked inscriptions to include the words Arandora Star, for the first time, has also featured (Figure 4), indicating continuing emotional-affective presencing. Finally, in a few cases, memorialisation continues as identified bodies in unmarked graves are ‘found’; for example, Antonio Nardone at Bun-na-Margey Friary, County Antrim in 2021 and, in 2023, Francesco D'Inverno at Girvan, Ayrshire.

In addition to these cultural practices of AS families, another group of headstones shine light on political aspects of the deathscape. These yet more emblematic documents in stone are located in cemeteries on the Western Isles of Barra, South Uist, Colonsay, Oronsay and Islay, where Italian victims came ashore. During the period of oblivion, these graves remained completely ‘hidden’, their existence virtually unknown to the Italian community before 1985 and their uncovering through the publication of Pietro Zorza's book Arandora Star: Il Dovere di Ricordarli. The bodies that washed-up on Hebridean beaches in August and September 1940 were initially buried where found and, with one exception,Footnote 9 were then transferred to local cemeteries and churchyards where, like all identifiable victims, they were marked with wooden ‘T’ shaped crosses. At a later date, some 15 to 20 years after the war, the graves of five Italians, from the total of eight identified bodies, were marked with granite headstones. These headstones are of a standardised style with the victim's name at the top and Italian inscription. Where known, date of birth, ‘nato il …’, followed by the month, in full (gennaio, febbraio etc.), and the year, is given. Dates of death, ‘deceduto il …’ vary from the day of the sinking, ‘2 luglio 1940’ to ‘6 settembre 1940’, when the last body came ashore. More correctly, in one case, ‘rivenuto il …’ appears. A similar limestone headstone on Rathlan Island, County Antrim, reads ‘sepolto il …’, giving the date 12 agosto 1940. Differing from the individual and family graves mentioned above, these tombstones do not mention the Arandora Star, or reference being lost at sea. Under the religious symbol of a centrally carved Latin cross, they bear the inscription ‘morto per la patria’ – died for the fatherland/homeland/their country. This begs the question of how these identical gravestones, with the morto per la patria inscriptions came about, and how they can be read as documents in stone.

Zorza recounts being alerted to possible ‘Italian’ graves on the islands and how a retired policeman on Colonsay, responsible for the 1940 burials with the wooden ‘T’ markers, reported that ‘later, the Government placed stone crosses, as in war cemeteries with the name and inscription’ (Reference Zorza1985, 52). This governmental intervention happened initially through a resolution of the Imperial War Graves Commission dated 28 January 1944, which on behalf of the Home Office undertook the care of civilian internee graves in the UK (CWGC/2/2/1/256, A/79/1 1944), and later through The British Commonwealth–Italian War Graves Treaty, signed in Rome, 27 August 1953. Although largely concerned with British war graves in Italy, an ‘exchange of notes’ the same day between the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the UK government agreed provision for similar treatment of Italian graves on British soil, the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) assuming responsibility.

For the different nationalities of graves under their care, the CWGC established 20 shape variations to a standard, slightly rounded top, 815mm tall headstone. The Italian variation is described as ‘similar to the standard Commission pattern except for the tops which have an ogee shape with a bite out of each corner’ (CWGC/ADD/1/3/71 n.d.). A total of 621 Italian Second World War graves worldwide are listed by CWGC (CWGC database), 511 of which are in the UK, mainly of Italian prisoners-of-war who died of natural causes while held captive in this country. The majority of these POWs are buried at the Military Cemeteries of Brookwood in Surrey (339) and Beachley in Gloucestershire (30), with the residue (112) buried in war and service plots ‘scattered’ nationwide. As well as the 481 POWs, 30 Italian civilian internees are CWGC listed as having died in Britain during the war, 23 of whom have the Italian CWGC headstone.Footnote 10 Of these, 13 men are buried on the Isle of Man, including AS survivor Osvaldo Girolami, four are located, curiously, at Brookwood Military Cemetery and six are Arandora Star victims (five buried in Scotland, one in Northern Ireland). On all 23 civilian internee headstones, the morto per la patria inscription is present (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Commonwealth War Graves Commission headstones. Left: Walfrido Sagramati, Isle of Colonsay: ‘Morto per la patria’. Right: Enrico Muzio, Isle of Barra: ‘Morto per la patria’; photos Alan Davis

Whilst morto per la patria is an entirely fitting epitaph for the Italian POW combatants, its significance and inference on the gravestones of AS victims and other civilian internees, appears both inappropriate and ambiguous. It seems to imply that by being interned these individuals had been actively doing something for Italy and had been sacrificed for Italy's war effort. As patriotic rhetoric in commemorative inscription and official meaning-making can constitute ‘exercises in propaganda’ (Mackenzie Reference Mackenzie, Evans and McCarthy2020, 179), morto per la patria could be perceived as politicised statement by the Italian authorities in valorising, even glamorising these civilian deaths by turning them into war fallen. Yet, the AS victims died as a result of their nationality, rather than for their country.

The use of Italian language on the gravestones might be considered apt. Yet, it conceivably upholds the wartime narrative of ‘enemy within’ and, at the same time, disregards the ‘divided loyalties’ of the victims. Many AS victims had not only lived in Britain for decades, but also had sons serving in the British armed forces, such as AS victim Quinto Santini, whose son died serving with the Kings Own Scottish Borderers (Figure 4). Moreover, as there were both naturalised British subjects among those lost, such as Antonio Mancini of Ayr, and antifascists, such as Dieco Anzani, any notion of these men having died ‘for Italy’ is unfitting. Of equal significance, however, is the absence of recognition of civilian status on either the AS or the other internee CWGC headstones. The Commission's agreement with the Italian government stated that headstone detail should specify ‘“Rank”, “Name”, “Date of Death”, “Branch of Service”’,Footnote 11 all of which are inscribed on the POW headstones. For the internees, a corresponding inscription is present only on one final CWGC headstone located on Islay – that of an unidentified Italian AS victim. Over two lines, the inscription ‘Sconosciuto Italiano, Civile Internato’, appears in the space for Rank and Branch of Service (Figure 5). Thus, it could be argued that had the Italian authorities so wished, the words ‘Interned Civilian’ could have been inscribed on the named AS headstones, and also on those of other Italian civilians who died whilst interned.

Figure 4. Quinto Santini, ‘lost at sea, Arandora Star, 2nd July 1940’, and his son Ralph Santini, ‘killed in action, Caen, Normandy, 19th July 1944’; photo Raffaello Gonnella

Figure 5. Commonwealth War Graves Commission headstone, Island of Islay, ‘sconosciuto italiano civile internato, deceduto il 10 agosto 1940’; photo Alan Davis

Despite acknowledgement of civilian status on the sconosciuto italiano stone, we nevertheless perceive additional militaristic allusion through borrowing of the concept of the ‘unknown soldier’, who makes the ultimate noble sacrifice in dying ‘for his country’. Drawing on the metaphorical semiotics of the sconosciuto italiano as representing all those either lost at sea or recovered but unidentified, and offering a hypothetical space for community mourning to reside (Colpi Reference Colpi2020, 396), a photograph of this gravestone formed the cover of Zorza's book (Reference Zorza1985). Yet, only more recently with the diffusion of internet images and spreading knowledge of this particular tombstone's existence, could significant notional comfort feasibly be drawn by victims’ families. Even so, during the war itself, Mia Woodruff of the Italian Internees Aid Committee, felt that knowledge of ‘a sort of “Unknown Internee” grave’ would be of great consolation to the bereaved (Mackenzie Reference Mackenzie1969, 96). Perhaps at her suggestion the sconosciuto italiano gravestone materialised. Like the other CWGC headstones, however, this stone does not mention the AS,Footnote 12 and the date of death is carved as 10 August 1940, conceding no acknowledgement therefore of possibly the most significant date and event in the recent history of the Italian presence in Britain.

At a distance of around two decades from the war's end to installation of the AS headstones,Footnote 13 CWGC files amply demonstrate the diplomatic and practical efforts of both British and Italian governments in rebuilding traditional ties of friendship and co-operation. The seeming unwillingness of the Italian authorities to differentiate by inscription any of the internment deaths from those of the POWs is conceivably evidentiary of postwar sensitivities in avoiding controversial topics. At just 23 civilian internee CWGC headstones, perhaps too insignificant a number to be accorded apposite official inscription, this oversight nonetheless arguably compromises dignity in death and raises questions for descendants and historians alike. Consideration of Italian civilian internee graves receives scant mention in CWGC files, and as far as research could detect, the Arandora Star none at all. Since the British Commonwealth–Italian War Graves Treaty did not include Eire, none of the 12 identified Italian victims that came ashore in southern Ireland have CWGC headstones, and only half of these graves have headstones at all. For the latter group, the Italian government played no part; local people or victims’ families erected the headstones, which consequently manifest in a variety of shapes and styles, with varied inscriptions.

As in Italy, where the AS was ‘twice forgotten’ for political reasons, and civic commemoration in communities of origin rarely included AS victims in memorials to the ‘caduti di guerra’ (Colpi Reference Colpi, Carr and Pistol2023, 50, 54), it can be concluded that the Italian government's specification for CWGC civilian internee headstones in this country reflected similar reticence. The resultant seemingly conscious omission of civilian status on all internees’ gravestones, and their simultaneous inclusion amongst the war-fallen by the morto per la patria inscription, reiterates the questions and patterns in war memory that surround inclusion and exclusion of who can be remembered, and in what terms (Butler Reference Butler2016). The burial of civilian internees at Brookwood Military Cemetery and inclusion of AS victims in the Italian Embassy annual remembrance service held there in November, are further examples of these entangled questions. Overall, the less than elucidatory inscriptions on the CWGC Arandora Star and other civilian internee headstones act to submerge the wartime narrative of the Italian community and disappoint as historical documentation.

Ecologies of loss and remembrance

Although few in number and deficient in detail, within the collective memory an important role can nonetheless be assigned to the island graves and their Irish counterparts in fashioning an imaginative geography of the sinking. The remote locations where the victims, named and perhaps more so unnamed, lie, magnify the sense of tragedy and inaccessible loss. It is now generally known that scores of unidentified bodies were thus buried,Footnote 14 a fact that weighs on the collective affective-emotional memory, representing an invisible topography of mourning or ‘emotional deep mapping’ (Maddrell Reference Maddrell2016, 169). Yet, for the families whose loved ones were recovered, identified and buried at the outermost margins of the British Isles, there was no connection or ‘attachment to place’. Normally intense sites of mourning, the spatial segregation of these graves from the living generated yet more disenfranchisement. Only in one case did the victim's place of burial become a site of mourning, and also one of subsequent family burial. Russian-born Vera Maschova relocated from London to live on Barra to be near her husband Oreste Fisanotti's grave. Although Vera moved in 1959 to Glasgow, on her death in 1975 her body was returned to Barra, a supplementary stone marker added at the base of the CCWG headstone (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Oreste Fisanotti and Vera Maschova, Isle of Barra; photo Alan Davis

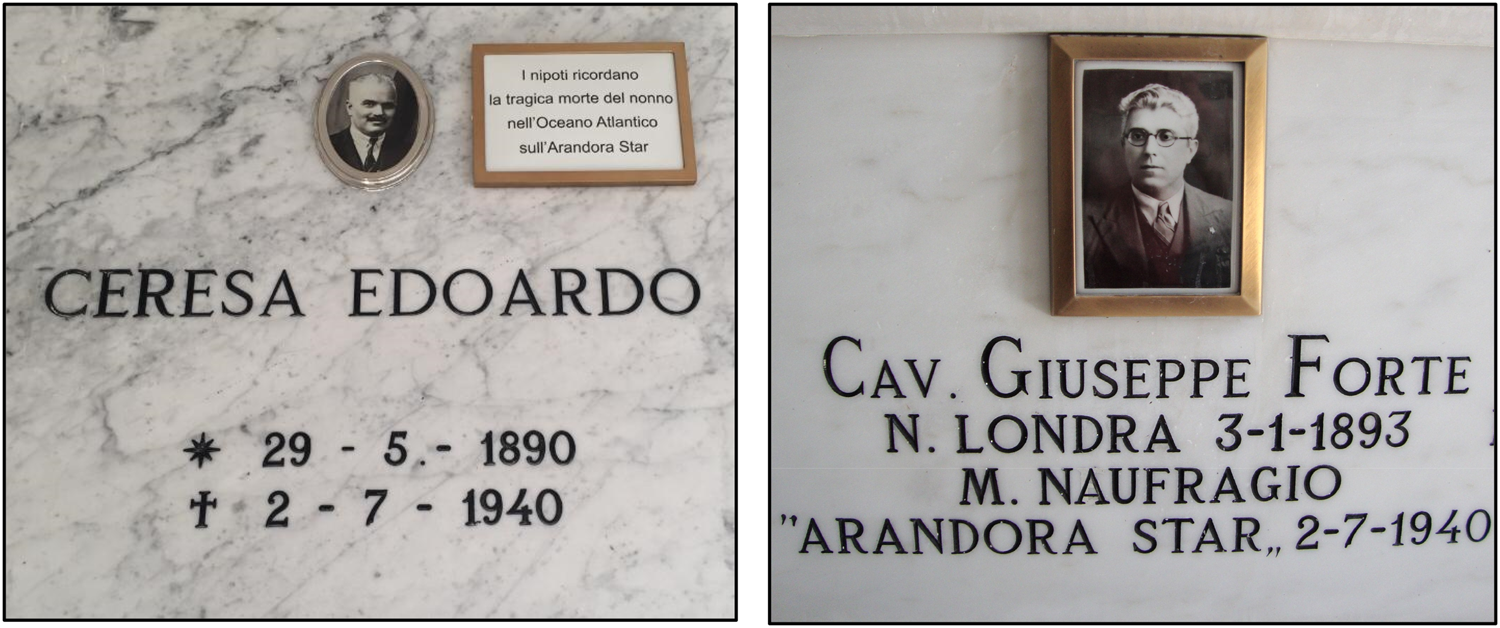

As a consequence of spatial disenfranchisement, another cultural practice worthy of discussion in the deathscape, some remains were exhumed and either repatriated ‘home’ to Italy or transferred to places of residence in Britain. Exhumation is often a preferred mechanism to empower families and re-dignify victims (Henderson, Nolin and Peccerelli Reference Henderson, Nolin and Peccerelli2014). Repatriation of the dead has been explored for other migrants in Britain where both cultural heritage and disenfranchisement in death processes have been responsible (Gardner Reference Gardner1998; Hunter Reference Hunter2016). For AS victims’ families, it is not unreasonable to argue that repatriation of bodies also responded to negative wartime experience causing disassociation from Britain. Certainly many of the 442 victims’ families are untraceable in this country today, indicating return to Italy as contended by Benedetti (Reference Benedetti2008, 45), and substantiated through interviews in Italy (Balestracci Reference Balestracci2008), or suggesting migration elsewhere. Known repatriated exhumations include AS victims Vilfrido Sagramati from Colonsay to Rome and, from Ireland, Luigi Tapparo to Bollengo (To) and Francesco Rabaiotti to Bardi (Pr). Others, such as the remains of Giuseppe Del Grosso, originally buried on Colonsay, were later reinterred at St Kentigern's cemetery, Glasgow, where the family had created a sense of ‘insideness and continuity’ (Boccagni Reference Boccagni2017). Likewise, Giovanni Marenghi, originally from Bardi (Pr) and buried at Termoncarragh cemetery, County Mayo, was reinterred at Pontypridd in Wales, and both Matteo Fossaluzza from Cavasso (Pn) and Luigi Giovanelli from Bardi (Pr), initially buried in Sligo and Tory Island, Donegal respectively, were later reinterred at Islington and St Pancras cemetery, London. Yet as Baldassar (Reference Baldassar2011) argues, ‘home’ in migration is never a crystallised locality as there will always be affective circulations between origins and new settings. This type of transnational belonging is evidenced through individual documents in stone to AS missing installed at Italian cemeteries or other local sites. Often, these commemorate victims unnamed on UK memorials, like Edoardo Ceresa at Bollengo (To) and Giuseppe Forte at Casalattico (Fr), (Figure 7). These bodily transferences and commemorations of the missing also typify Italian normative behaviour through religious mechanisms and ‘cult of the dead’ whereby it is important to maintain active and devoted relationships with the deceased (Goody and Poppi Reference Goody and Poppi1994). Any considered neglect of the dead is generally frowned upon, hence undertaking costly exhumation. The substantial numbers of Italian POWs exhumed from British cemeteries and repatriated to Italy further highlights this practice. In 1982, for example, the Seventh Meeting of the Commonwealth-Italian Joint Committee reported 35 repatriations of POW remains since the previous meeting in 1977 – a rate of seven exhumations annually (CWGC/1/2/D/12/4/13 1982).

Figure 7. Documents in stone: Italy; photos Ceresa and Forte families

The case of Giuseppe Del Grosso expresses several threads of the AS deathscape. Aged 51 in July 1940, he had lived in Scotland for 32 years and, although a member of the Glasgow fascio,Footnote 15 is considered representative of the elderly, ‘innocent’ Italian victim.Footnote 16 His narrative is evocative in that not only was his body found, identified, and subsequently memorialised in four places – Colonsay, AS memorials in Glasgow and Borgotaro in Italy, and on a large family tombstone at St Kentigern's cemetery – but a rare document trail also exists. Correspondence held in a Home Office file seeks compensation for missing personal items and conveys the bereaved family's overwhelming sense of loss and injustice (HO 214/3 1941). This dialogue has been likened to a crusade for recovery of identity and intimate family memory, representing something well beyond the items’ material value (Bernabei Reference Bernabei, Rose and Rossini2000, 56). Early exhumation of Del Grosso's body from Colonsay, in March 1941, and reinterment at St Kentigern's (St Kentigern's Cemetery Lair Book), further attest to the family's determination to regain some agency over the tragedy and also explains the absence of a CWGC headstone to Del Grosso on the island. This absence and indeed of the bodily remains, did not, however, diminish the absent-presence of Del Grosso. Combined with dedication to AS memory by the islanders (Colpi Reference Colpi2020), his origins in the province of Parma, Emilia Romagna, foregrounded his memory. The Region has long advanced and supported the interests of its emigrants (Migrer), where just under a quarter of all AS victims and survivors originated and where Bardi, the epicentre pocket of affect, is located (Colpi Reference Colpi, Cesarani and Kushner1993a, 179). Via l'Associazione Parmigiani in Scozia, strong links between Borgotaro, the Italian regional and provincial administrations and the island culminated in the first AS civic memorial in Britain being unveiled on Colonsay in 2005. Remembering ‘the more than 800 others who perished’, the memorial plaque is ‘sacred to the memory of Giuseppe Del Grosso’, a form of words often associated with unexpected death, especially when bodies are not recovered (Foote Reference Foote2003).

The Italian Cloister Garden and Arandora Star Memorial, Glasgow

Discussion on the evolution and socio-political context of AS commemoration in Britain and Italy can be found elsewhere (Chezzi Reference Chezzi2014; Giudici Reference Giudici and Gourievidis2014; Ugolini Reference Ugolini2015; Colpi Reference Colpi2020, Reference Colpi, Carr and Pistol2023). As Maddrell states, ‘memorials and the practices that they prompt help us to understand and appreciate something of the experiences and meaning-making of the bereaved, including that of absence-presence’ (Reference Maddrell2013, 510). Evaluation here concerns the role of significant individuals, identity, and materiality. As already noted, missing bodies and different types of disenfranchisement created a ‘bottling-up’ effect, the long silence causing strong cravings for recognition.

The arrival of Mario Conti, Italian on both sides of his family, from Aberdeen where he had been bishop since 1977, to the Archdiocese of Glasgow in 2002, ushered in a leadership that curated and promoted Italian interests both within the Catholic Church and the wider secular establishment. In 2004, working with the Italian authorities, the Lord Provost of Glasgow and Solicitor General for Scotland, Conti signalled his mission to unite and mobilise by organising a mass gathering of 650 Italians in Glasgow. He understood that such an assembly, unprecedented since before the war, indicated not only rehabilitation but also continuation: ‘a long-overdue opportunity to come together, recalling their roots but also recognising their contribution’ (BBC News 2004). Thus, Conti came to symbolise an embodied campanile around which the Italian community in Scotland could muster and identify.

Yet, as a natural and dynamic spearhead for AS remembrance, Conti's influence extended beyond Scotland, forming an important element in the memoryscape and one that previous scholars have overlooked. His participation in 2008 at Liverpool's AS memorial installation as a ‘site of conscience’ (Lloyd Reference Lloyd2022), served both to enact long-overdue funerary rituals for the bereaved descendants present and, crucially, officially added the Church to the other attending diplomatic, institutional and civic representations. While acknowledging the requiem-like Mass and prayers over memorial-wreaths floated on the Mersey as giving closure and dignity in death for attending relatives, the statement that the commemorative rituals were ‘officiated by a priest’ (Ugolini Reference Ugolini2015, 97), not only collapses an archbishop's authority in endowing an appropriate sense of occasion but obscures Conti's role in AS history.

Formidable ability in negotiation, alliance building and financial savvy, alongside a passion for Catholic history, enabled and inspired Conti to embark on a remarkable programme of restoration and improvement of St Andrew's Cathedral, one that spotlighted the Arandora Star (Sweeney Reference Sweeney2008; Giornale di Barga 2009). Conscious of the embedded grief surrounding the ‘forgotten tragedy which has never been appropriately marked’, Conti recognised the need for public, national level, memorialisation (Italian Cloister Garden). His £5m refurbishment between 2009 and 2011 has been labelled ‘the most significant modern renovation of Scotland's Catholic patrimony’ (Hudson Reference Hudson2022), and the monument these works integrated as the most important AS commemoration of the British and Italian memorial infrastructure (Colpi Reference Colpi2020, 407). However, as Sabine Marschall astutely observed (Reference Marschall2020, 4), close reading of a monument's reception reveals much about the complexities of inter- and intra-group relations, as transpired. The Cathedral's embellishment was criticised as extravagant, the AS memorial characterised in negative and discriminatory terms (McKenna Reference McKenna2012), while exclusive allocation of external space to Italian interests created tension within the Irish community. Catholic factionalism notwithstanding, the AS memorial in Scotland overshadows those in England and Wales (Colpi Reference Colpi, Carr and Pistol2023, 56–57), and can, in large part, be attributed to the status, ability and commitment of Mario Conti. Correctly judging the auspicious historical moment, after the success of Liverpool, and securing political support from Scotland's First Minister (BBC News 2011), Conti brought the Italian Cloister Garden and Arandora Star Memorial in Glasgow into being. His successful strategy deliberately and tactically involved all the Italian community (Colpi Reference Colpi2020), who underwrote the memorial.

In addition to assuaging AS memory, the material presence of the large-scale memorial on the physical landscape succeeded in mapping Italians into the past, present and future social space of Scotland. Indeed, Conti envisioned a space that ‘provided an opportunity for marking the contribution which the Italian Scots have made to Scottish society’ (Conti Reference Conti2011). The making of the memorial enabled collective movement beyond previously prescribed boundaries of Italian identity. By marking the former ‘fault-line’ of the war, the memorial renegotiated Italian belonging, and in permanently displaying AS memory in a city centre location, Italian heritage forced itself into the nation's history, reminiscent of Italian monument building in New York (Deschamps Reference Deschamps2015). As an integral part of the architecture and culture of Glasgow, commenting on the Italian narrative, the Italian Cloister Garden today forms one of the city's attractions, drawing visitors especially during the annual ‘Doors Open Days Festival’ (Glasgow Doors Open). Moreover, it acts as the reference point for Scottish/Italian dialogue and for visiting Italian dignitaries – for example, the inaugural Scottish visit of Italian ambassador Inigo Lambertini in May 2023 (ANSA 2023). This contact with ‘Italy’ reinforces cultural identity and encourages transnational distinctiveness. Contiguity with the Cathedral fosters intersection with Church rhythms and the socio-religious devotion to the dead mentioned previously. That the missing dead of the AS are now ‘situated’ and their memory no longer disenfranchised, but manifest in material presence, holds spiritual, political and cultural significance.

Yet, a monument's affecting presence is subject to fluidity as new generations see and interpret its role and relevance differently (Ruberto and Sciorra Reference Ruberto and Sciorra2022). Italian migration to Scotland, like the rest of the UK, has experienced waves of ‘new’ migrants since the 2000s (Scotto Reference Scotto2015), who tend to be socially and culturally distinct from descendants of the ‘old’ migration (Colpi Reference Colpi2017). While many new migrants may be aware of the AS memorial, few are emotionally invested or actively engaged. Moreover, those descendants of the ‘old’ migration intimately involved with custodianship are mostly aged 50 or 60, and there appears to be limited participation by younger, less emotionally affected, generations. The passing of Mario Conti in 2022 has also elicited some behavioural shifts. The non-Italian incumbent archbishop cancelled the annual ‘All Souls’ Mass dedicated to the AS due to declining numbers, and was supported in this by the association ‘ItalianScotland’. The Italian Garden Improvement Group (IGIG) now advises that the monument commemorates all AS victims, perhaps hoping to broaden its appeal (Glasgow Doors Open). Inclusion of reference to wider issues of migration and asylum today or even of other, smaller and less cohesive segments of the Italian community whose wartime experiences differed and have arguably been silenced by the dominant AS narrative (Ugolini Reference Ugolini2015), could perhaps further influence future relevance of the memorial. There is no doubt that the AS offers an entry point for new generations studying migration-related deaths, especially issues of missing bodies, identification and burial practice of victims, like those wrecked on southern Italian shores (Mirto et al Reference Mirto, Robins, Horsti, Prickett, Ruiz Verduzco, Toom, Cuttitti and Last2020).

With Italian identity buttressed by the physical presence of the monument, it is in, and from, this space that the memory choreographers mentioned earlier locate their platform to perform as ‘embodied texts’ of the Arandora Star (Maddrell Reference Maddrell2016). The IGIG post-generation custodians are concerned with the upkeep and improvement not only of the Garden but of the memory itself. Their labours can best be illustrated by two examples.

Adoption by the activists of AS victim Francesco D'Inverno, mentioned above, recently produced newsworthy results (Rinaldi Reference Rinaldi2023). His body had been lying in an unmarked and, prior to 2023, unidentified grave at Doune cemetery, Girvan, but successful collaboration between IGIG and local CWGC representatives culminated in the erection of a family-type headstone in April 2024 (see Introduction this issue). IGIG are also pursuing official recognition of D'Inverno's death by the Italian authorities, which should validate inclusion in CWGC's database. A civic reception followed the gravestone's installation, involving the AS ‘community of interest’ (Colpi Reference Colpi, Carr and Pistol2023, 59), with guests invited from elsewhere in the UK and from Italy. These events highlight the agency of ‘Italians’ in Scotland today as well as integration of the Arandora story into the war's narrative.

Another instance of IGIG's efforts is articulated through a commemorative mosaic, dating to 1975. Depicting the torpedo explosion, with the words ‘non vi scorderemo mai’ (‘we will never forget you’) superimposed, the artefact represents the first community-wide remembrance in Scotland. It offered a channel for collective mourning and a manifestation of materiality, giving it particular emotional-affective intensity. Acting as a carrier of ‘attached’ feelings and meanings, the mosaic's impact sustains over time (Mannergren Selimovic Reference Mannergren Selimovic2022, 224). As Heersmink attests, such memory-evoking objects, like the AS mementos discussed earlier, play an essential role in remembering a cultural past (Reference Heersmink2023). When prominently displayed at the Italian Cloister Garden's opening in 2011 (Figure 8), and highlighting the vulnerability of small artefacts in memorialisation, the portable mosaic mysteriously disappeared. Causing consternation within the Italian community (Goodwin Reference Goodwin2016), after a decade-long search by IGIG, it was eventually recovered in 2022. At the time of writing, the heritage campaigners were planning to tour the mosaic to pockets of affect, such as Ayr, and other cities like Dundee, accompanying its exhibit by AS talks. With the sinking and its aftermath no longer within living memory, this proposal demonstrates the mediation of ‘cultural artefacts’ in reawakening identities, encouraging non-forgetfulness and promoting new awareness (Heersmink Reference Heersmink2023). Fundamentally, however, it is the AS Memorial that, since its inception, has stimulated the conceptual energy and material focus for the steady flow of press coverage that helps generate and sustain wider interest in the tragedy (Sweeney Reference Sweeney2008; Campsie Reference Campsie2020).

Figure 8. Archbishop Mario Conti, St Andrew's Cathedral, at the opening of the Italian Cloister Garden and Arandora Star Memorial, May 2011, with material objects – a model of the ship and 1975 commemorative mosaic; photo Terri Colpi Archive

Conclusion

The primary focus in this paper has been introducing the deathscape paradigm as a lens through which to look afresh at AS remembrance. In so doing, the affective power and presence of absence has necessarily been a pervasive theme. Discussion has revealed how multiple layers of disenfranchisements, missing bodies, lack of ritual or sanction in mourning have influenced affective-emotional memory and the behaviours of victims’ relatives. These subjectivities transmitted to post-generations, and in Scotland, where a visionary leader serendipitously emerged to create the largest AS memorial in the UK or Italy, it has been shown how eventually the Italian social landscape itself was redefined through the formation of a liberated Italian identity and heritage activism. Additionally, investigation of hitherto uncharted individual memorialisation has exposed a crucial material element of the deathscape, and has furthermore engendered a ‘presencing’ of the AS. In probing these documents in stone, it has been argued that cultural practice in familial gravestones acted to unbind previous disenfranchisement, while political patriotic rhetoric on official headstones acted to both confuse and conceal the AS and wartime internment narrative, also indicating a fundamentally ambiguous treatment of the dead. Ultimately, the fragmentation of the Arandora Star deathscape is kaleidoscopic, at the same time interwoven yet fractured; this very complexity embodies the essence of the enduring affective-emotional attachment.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers and Professor Derek Duncan who provided valuable comments and suggestions for this article.

Competing interests

The author declares none.

Dr Terri Colpi is an Honorary Research Fellow at the University of St Andrews specialising in the migration, history and geographies of Italian communities in Britain. She has published three books and a range of articles and book chapters on these subjects, including most recently on the Arandora Star: ‘Chaff in the Winds of War? The Arandora Star, Not Forgetting and Commemoration at the 80th Anniversary’, Italian Studies Reference Colpi2020, 75 (4): 389–410, and ‘Legacy and Heritage of the Arandora Star Tragedy: A Transnational Perspective’, in Internment in Britain and Internment of Britons edited by G. Carr and R. Pistol, 47–66. London: Bloomsbury, Reference Colpi, Carr and Pistol2023. She is historical advisor to the Arandora Star UK National Memorial Trust.