1. Introduction

Gelfand’s proof of Wiener’s lemma [Reference Gelfand20], which asserts that the reciprocal of a function with absolutely convergent Fourier series that does not vanish anywhere has absolutely convergent Fourier series too, was central to the development of Banach-algebraic ramifications of harmonic analysis. Wiener’s lemma may be rephrased as follows: the algebra of absolutely convergent Fourier series is inverse-closed when embedded into the algebra of all continuous functions on the unit circle. In the present article, we shall be concerned with algebras that have even a stronger property, namely that the norm of an invertible element is a function of the norm of the element and its supremum norm of its Gelfand transform (see Theorem 1.1); a property that the algebra of absolutely convergent series lacks.

When A is a unital Banach algebra and ![]() $i\colon A\to B$ is a unital continuous injective homomorphism, we say that A admits norm-controlled inversion in B, whenever there exists a function

$i\colon A\to B$ is a unital continuous injective homomorphism, we say that A admits norm-controlled inversion in B, whenever there exists a function ![]() $h\colon (0, \infty)^2 \to (0, \infty)$ so that for every element

$h\colon (0, \infty)^2 \to (0, \infty)$ so that for every element ![]() $a\in A$, which is invertible in

$a\in A$, which is invertible in ![]() $B,$ we have

$B,$ we have

Since the embedding i is injective, an invertible element a in algebra A remains invertible in B (strictly speaking, i(a) is invertible); however, in this case, the norm-controlled inversion of A in B implies that the inverses are actually in A (i.e., i(A) is inverse-closed in B).

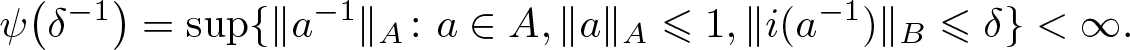

Following Nikolskii [Reference Nikolski29], for δ > 1, we say that a Banach algebra A is δ-visible in B, whenever

\begin{align}

\psi\big({\delta}^{-1}\big) = \sup\{\|a^{-1}\|_A \colon a\in A, \|a\|_A \leqslant 1, \|i(a^{-1})\|_B \leqslant \delta\} \lt \infty.

\end{align}

\begin{align}

\psi\big({\delta}^{-1}\big) = \sup\{\|a^{-1}\|_A \colon a\in A, \|a\|_A \leqslant 1, \|i(a^{-1})\|_B \leqslant \delta\} \lt \infty.

\end{align}Then A admits norm-controlled inversion in B if and only if it is δ-visible in B for all δ > 1. Should that be the case, the norm-control function h can be arranged to be

\begin{align}

h(\|a\|_A, \|i(a^{-1})\|_B) = \frac{1}{\|a\|_A}\psi\big( {\|a\|_A\|i(a^{-1})\|_B}\big).

\end{align}

\begin{align}

h(\|a\|_A, \|i(a^{-1})\|_B) = \frac{1}{\|a\|_A}\psi\big( {\|a\|_A\|i(a^{-1})\|_B}\big).

\end{align} For a commutative (*-)semi-simple Banach (*-)algebra A we say, for short, that A admits norm-controlled inversion, whenever it admits norm-controlled inversion in ![]() $C(\Phi_A)$, the space of continuous functions on the maximal (*-)ideal space

$C(\Phi_A)$, the space of continuous functions on the maximal (*-)ideal space ![]() $\Phi_A$ of A, when embedded by the Gelfand transform. (For a commutative (*-)semi-simple Banach (*-)algebra, the Gelfand transform is injective, see also [Reference Doran15, proposition 30.2(ii)].)

$\Phi_A$ of A, when embedded by the Gelfand transform. (For a commutative (*-)semi-simple Banach (*-)algebra, the Gelfand transform is injective, see also [Reference Doran15, proposition 30.2(ii)].)

The Wiener (convolution) algebra ![]() $\ell_1(\mathbb Z)$ is a primary example of a commutative Banach *-algebra without the norm-controlled inversion in

$\ell_1(\mathbb Z)$ is a primary example of a commutative Banach *-algebra without the norm-controlled inversion in ![]() $C(\mathbb T)$, the algebra of continuous functions on the unit circle. Indeed, in [Reference Nikolski29], Nikolskii showed that for

$C(\mathbb T)$, the algebra of continuous functions on the unit circle. Indeed, in [Reference Nikolski29], Nikolskii showed that for ![]() $\delta \geqslant 2$ we have

$\delta \geqslant 2$ we have ![]() $\psi (\delta^{-1}) = \infty,$ where ψ is given in (1.1). The same conclusion extends to convolution algebras

$\psi (\delta^{-1}) = \infty,$ where ψ is given in (1.1). The same conclusion extends to convolution algebras ![]() $\ell_1(G)$ for any infinite Abelian group G that lack norm-controlled inversion in

$\ell_1(G)$ for any infinite Abelian group G that lack norm-controlled inversion in  $C(\widehat{G})$, the algebra of continuous functions on the Pontryagin-dual group to G, but this behaviour appears rather exceptional. On the positive side, various weighted algebras of Fourier series (see [Reference El-Fallah, Nikol’skii and Zarrabi17]) as well as algebras of Lipschitz functions on compact subsets of Euclidean spaces enjoy the norm-controlled inversion.

$C(\widehat{G})$, the algebra of continuous functions on the Pontryagin-dual group to G, but this behaviour appears rather exceptional. On the positive side, various weighted algebras of Fourier series (see [Reference El-Fallah, Nikol’skii and Zarrabi17]) as well as algebras of Lipschitz functions on compact subsets of Euclidean spaces enjoy the norm-controlled inversion.

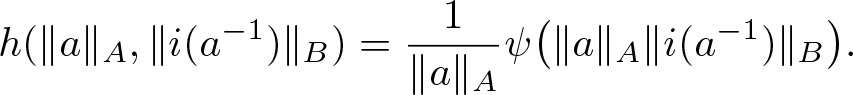

Norm-controlled inversion is a consequence of smoothness of the embedding as observed by Blackadar and Cuntz [Reference Blackadar and Cuntz9]. More specifically, let ![]() $i\colon A\to B$ be a unital injective homomorphism of unital Banach algebras. (By a subalgebra of a unital algebra, we shall always mean a unital subalgebra. Likewise, all homomorphisms between unital Banach algebras are assumed to preserve the unit.) Then A is a differential subalgebra of B whenever there exists D > 0 such that for all

$i\colon A\to B$ be a unital injective homomorphism of unital Banach algebras. (By a subalgebra of a unital algebra, we shall always mean a unital subalgebra. Likewise, all homomorphisms between unital Banach algebras are assumed to preserve the unit.) Then A is a differential subalgebra of B whenever there exists D > 0 such that for all ![]() $a,b\in A$ we have

$a,b\in A$ we have

When A and B are Banach *-algebras, we additionally require that i is *-preserving (hence it preserves the modulus); we omit the symbol i, when the map i is clear from the context (for example, when it is the formal inclusion of algebras). Differential subalgebras (especially of C*-algebras) have been extensively studied, see, e.g., [Reference Gröchenig and Klotz21, Reference Gröchenig and Klotz22, Reference Kissin and Shulman24, Reference Samei and Shepelska31].

A unital Banach *-algebra A is symmetric, if the spectrum of positive elements is non-negative (i.e., ![]() $\sigma (A(a^{*}a)) \subseteq [0, \infty)$ for all

$\sigma (A(a^{*}a)) \subseteq [0, \infty)$ for all ![]() $a \in A$), which means that for any

$a \in A$), which means that for any ![]() $a\in A$ the element

$a\in A$ the element ![]() $1+a^*a$ is invertible (see [Reference Doran15, chapter 6] for further characterizations). In the sequel, we shall make use of [Reference Gröchenig and Klotz21, theorem 1.1(i)] that we record below:

$1+a^*a$ is invertible (see [Reference Doran15, chapter 6] for further characterizations). In the sequel, we shall make use of [Reference Gröchenig and Klotz21, theorem 1.1(i)] that we record below:

Theorem 1.1 Differential *-subalgebras of C*-algebras have norm-controlled inversion.

In particular, differential *-algebras of C*-algebras are symmetric.

Note that the condition of being a differential norm is a rather mild assumption, and norms satisfying (1.3) meet a weak form of smoothness as explained in [Reference Gröchenig and Klotz21, theorem 1.1(v)]).

In the present article, we investigate the possible connections between smoothness of an embedding of Banach algebras and topological stable rank 1 (which for unital Banach algebras is equivalent to having dense invertible group) with the openness of multiplication of a given Banach algebra A, i.e., the question of for which Banach algebras the map ![]() $m\colon A\times A\to A$ given by

$m\colon A\times A\to A$ given by ![]() $m(a,b)=ab$ (

$m(a,b)=ab$ (![]() $a, b\in A$) is open, that is, it maps open sets to open sets. The problem of which Banach algebras have open multiplication was systematically investigated by Draga and the first-named author in [Reference Draga and Kania16], where it was observed that unital Banach algebras with open multiplication have topological stable rank 1 but not vice versa. For example, matrix algebras Mn have topological stable rank 1 but multiplication therein is not open unless n = 1 [Reference Behrends7]. On the other hand, the problem of openness of convolution in

$a, b\in A$) is open, that is, it maps open sets to open sets. The problem of which Banach algebras have open multiplication was systematically investigated by Draga and the first-named author in [Reference Draga and Kania16], where it was observed that unital Banach algebras with open multiplication have topological stable rank 1 but not vice versa. For example, matrix algebras Mn have topological stable rank 1 but multiplication therein is not open unless n = 1 [Reference Behrends7]. On the other hand, the problem of openness of convolution in ![]() $\ell_1(\mathbb Z)$ is persistently open.

$\ell_1(\mathbb Z)$ is persistently open.

Various function algebras have been observed to have open multiplication (even uniformly, where a map ![]() $f\colon X\to Y$ is uniformly open whenever for every ɛ > 0 there is δ > 0 such that for all

$f\colon X\to Y$ is uniformly open whenever for every ɛ > 0 there is δ > 0 such that for all ![]() $x\in X$ one has

$x\in X$ one has ![]() $f(B(x,\varepsilon)) \supseteq B(f(x), \delta)$): spaces of continuous/bounded functions: [Reference Balcerzak, Behrends and Strobin2–Reference Behrends6, Reference Botelho and Renaud10, Reference Komisarski25, Reference Renaud30] and spaces of functions of bounded variation: [Reference Canarias, Karlovich and Shargorodsky11, Reference Kowalczyk and Turowska26]. The first main result of the article unifies various approaches to openness of multiplication. (All unexplained terminology may be found in the subsequent section.)

$f(B(x,\varepsilon)) \supseteq B(f(x), \delta)$): spaces of continuous/bounded functions: [Reference Balcerzak, Behrends and Strobin2–Reference Behrends6, Reference Botelho and Renaud10, Reference Komisarski25, Reference Renaud30] and spaces of functions of bounded variation: [Reference Canarias, Karlovich and Shargorodsky11, Reference Kowalczyk and Turowska26]. The first main result of the article unifies various approaches to openness of multiplication. (All unexplained terminology may be found in the subsequent section.)

Theorem 1.2 Suppose that A is a unital Banach *-algebra such that there exists an injective *-homomorphism ![]() $i\colon A\to C(X)$ for some compact space X such that A has norm-controlled inversion in C(X). Let us consider either case:

$i\colon A\to C(X)$ for some compact space X such that A has norm-controlled inversion in C(X). Let us consider either case:

•

$A = C(X)$,

$A = C(X)$,•

$A = E^*$ is a dual Banach algebra that shares with X densely many points.

$A = E^*$ is a dual Banach algebra that shares with X densely many points.

Then multiplication in A is open at all pairs of jointly non-degenerate elements.

Furthermore, suppose that i has dense range in C(X). If A has open multiplication, then the maximal ideal space of A is of dimension at most 1.

Theorem 1.2 applies, in particular, to ![]() $A = C(X)$, which may be interpreted as a complex counterpart of the main result of [Reference Behrends8].

$A = C(X)$, which may be interpreted as a complex counterpart of the main result of [Reference Behrends8].

Since the bidual of C(X) is isometric to C(Z) for some compact, zero-dimensional space (in particular, ![]() $C(X)^{**}$ has uniformly open multiplication), using Lemmas 2.1 and 2.2 we may record the following corollary.

$C(X)^{**}$ has uniformly open multiplication), using Lemmas 2.1 and 2.2 we may record the following corollary.

Corollary 1.2. Suppose that A is an Arens-regular Banach *-algebra that is densely embedded as a differential subalgebra of C(X) for some compact space X. Then ![]() $A^{**}$ has open multiplication at all pairs of jointly non-degenerate elements.

$A^{**}$ has open multiplication at all pairs of jointly non-degenerate elements.

The proofs of the main results of [Reference Canarias, Karlovich and Shargorodsky11, Reference Kowalczyk and Turowska26] centre around showing that the algebras of functions of p-bounded variation (for p = 1 and ![]() $p\in (1,\infty)$, respectively) are approximable by jointly non-degenerate products. Our theorem appears to be the first general providing sufficient conditions for openness in a given commutative Banach *-algebra (i.e., a self-adjoint function algebra).

$p\in (1,\infty)$, respectively) are approximable by jointly non-degenerate products. Our theorem appears to be the first general providing sufficient conditions for openness in a given commutative Banach *-algebra (i.e., a self-adjoint function algebra).

In [Reference Draga and Kania16, corollary 4.13], Draga and the first-named author proved that ![]() $\ell_1(\mathbb Z)$ does not have uniformly open convolution (whether it is open or not remains an open problem). We strengthen this result by showing that having unbounded exponent (that is, the condition

$\ell_1(\mathbb Z)$ does not have uniformly open convolution (whether it is open or not remains an open problem). We strengthen this result by showing that having unbounded exponent (that is, the condition ![]() $\sup_{g\in G} o(g) = \infty$, where o(g) denotes the rank of an element

$\sup_{g\in G} o(g) = \infty$, where o(g) denotes the rank of an element ![]() $g\in G)$ is sufficient for not having uniformly open convolution.

$g\in G)$ is sufficient for not having uniformly open convolution.

Theorem 1.4 Let G be an Abelian group of unbounded exponent, i.e., ![]() $\sup_{g\in G} o(g) = \infty$. Then convolution in

$\sup_{g\in G} o(g) = \infty$. Then convolution in ![]() $\ell_1(G)$ is not uniformly open.

$\ell_1(G)$ is not uniformly open.

By Prüfer’s first theorem (see [Reference Kurosh27, p. 173]), every Abelian group of bounded exponent is isomorphic to a direct sum of a finite number of finite cyclic groups and a direct sum of possibly infinitely many copies of a fixed finite cyclic group, so if one seeks examples of group convolution algebras with uniform multiplication, the only candidates to be found are groups that are effectively direct sums of any number of copies of a fixed cyclic group.

Finally, we establish a complex counterpart of Komisarski’s result [Reference Komisarski25] linking openness of multiplication in the real algebra C(X) of continuous functions on a compact space X with the covering dimension of X. In the complex case, C(X) has open multiplication if and only if X is zero-dimensional in which case multiplication is actually uniformly open with ![]() $\delta(\varepsilon) = \varepsilon^2 / 4$ (ɛ > 0). (see also [Reference Draga and Kania16, proposition 4.16] for an alternative proof using direct limits that does not depend on the scalar field; we refer to [Reference Engelking18] for a modern exposition of dimension theory and standard facts thereof.)

$\delta(\varepsilon) = \varepsilon^2 / 4$ (ɛ > 0). (see also [Reference Draga and Kania16, proposition 4.16] for an alternative proof using direct limits that does not depend on the scalar field; we refer to [Reference Engelking18] for a modern exposition of dimension theory and standard facts thereof.)

Theorem 1.5 Let X be a compact space. Then the following conditions are equivalent for the algebra C(X) of continuous complex-valued functions on X:

(i) C(X) has open multiplication,

(ii) C(X) has uniformly open multiplication,

(iii) the covering dimension of X is at most 1.

Moreover, the algebras C(X) have equi-uniformly open multiplications for all compact spaces of dimension at most 1.

A necessary condition for a unital Banach algebra to have open multiplication is topological stable rank 1, that is, having dense group of invertible elements. For a compact space X of dimension at least 2, this is not the case, so C(X) does not have open multiplication [Reference Draga and Kania16, proposition 4.4]. The proof of Theorem 1.5 is split into three cases.

• The first one uses a reduction to spaces being topological (planar) realizations of graphs. Here we rely on certain ideas from an unpublished manuscript of Behrends for which we have permission to include them in the present note. We kindly acknowledge this crucial contribution from Professor Behrends establishing the case of

$X=[0,1]$.

$X=[0,1]$.• Then we proceed via an inverse limit argument to conclude the result for all compact metric spaces of dimension at most 1.

• Finally, we apply a result of Madrešić [Reference Mardešić28] to conclude the general non-metrisable case from equi-uniform openness of multiplication of C(X) for all one-dimensional compact metric spaces X.

2. Preliminaries

2.1. Banach algebras

Compact spaces are assumed to be Hausdorff. All Banach algebras considered in this article are over ![]() $\mathbb C$, the field of complex scalars unless otherwise specified. We denote by

$\mathbb C$, the field of complex scalars unless otherwise specified. We denote by ![]() $\mathbb T$ the unit circle in the complex plane.

$\mathbb T$ the unit circle in the complex plane.

A Banach algebra A has topological stable rank 1, whenever invertible elements are dense in A if A is unital or in the unitization of A otherwise. Algebras whose elements have zero-dimensional spectra have topological stable rank 1 and include biduals of C(X) for a compact space X, the algebra of functions of bounded variation, or the algebra of compact operators on a Banach space; we refer to [Reference Draga and Kania16, §2] for more details.

2.1.1. Arens regularity, dual Banach algebras

As observed by Arens [Reference Arens1], the biudual of a Banach algebra may be naturally endowed with two, rather than single one, multiplications (the left and right Arens products, denoted ![]() ${\scriptstyle\square}$,

${\scriptstyle\square}$, ![]() $\diamond$, respectively). Even though these multiplications may be explicitly defined, the following ‘computation’ rule is perhaps easier to comprehend: for

$\diamond$, respectively). Even though these multiplications may be explicitly defined, the following ‘computation’ rule is perhaps easier to comprehend: for ![]() $f,g\in A^{**}$, where A is a Banach algebra, by Goldstine’s theorem, one may choose bounded nets

$f,g\in A^{**}$, where A is a Banach algebra, by Goldstine’s theorem, one may choose bounded nets ![]() $(f_j)$,

$(f_j)$, ![]() $(g_i)$ from A that are weak* convergent to f and g, respectively. Then

$(g_i)$ from A that are weak* convergent to f and g, respectively. Then

•

$f\, {\scriptstyle\square}\, g = \lim_j \lim_i f_j g_i$,

$f\, {\scriptstyle\square}\, g = \lim_j \lim_i f_j g_i$,•

$f \diamond g = \lim_i \lim_j f_j g_i$

$f \diamond g = \lim_i \lim_j f_j g_i$

are well-defined and do not depend on the choice of the approximating nets. A Banach algebra is Arens-regular when the two multiplications coincide. For a locally compact space X, the algebra ![]() $C_0(X)$ is Arens-regular, but a group G, the group algebra

$C_0(X)$ is Arens-regular, but a group G, the group algebra ![]() $\ell_1(G)$ (see §2.5) is Arens-regular if and only if G is finite [Reference Young33].

$\ell_1(G)$ (see §2.5) is Arens-regular if and only if G is finite [Reference Young33].

A dual Banach algebra is a Banach algebra A that is a dual space to some Banach space E whose multiplication is separately ![]() $\sigma(A,E)$-continuous. Notable examples of dual Banach algebras include von Neumann algebras, Banach algebras that are reflexive as Banach spaces, or biduals of Arens-regular Banach algebras, see [Reference Daws13, §5] for more details.

$\sigma(A,E)$-continuous. Notable examples of dual Banach algebras include von Neumann algebras, Banach algebras that are reflexive as Banach spaces, or biduals of Arens-regular Banach algebras, see [Reference Daws13, §5] for more details.

Suppose that ![]() $A = E^*$ is a dual Banach algebra and let

$A = E^*$ is a dual Banach algebra and let ![]() $i\colon A\to C(X)$ be an injective homomorphism for some compact space X. We say that A shares with X densely many points whenever there exists a dense set

$i\colon A\to C(X)$ be an injective homomorphism for some compact space X. We say that A shares with X densely many points whenever there exists a dense set ![]() $Q\subset X$ such that

$Q\subset X$ such that ![]() $i^*(\delta_x) \in E$ (

$i^*(\delta_x) \in E$ (![]() $x\in Q$), i.e., the functionals

$x\in Q$), i.e., the functionals ![]() $i^*(\delta_x)$ (

$i^*(\delta_x)$ (![]() $x\in Q$) are

$x\in Q$) are ![]() $\sigma(A,E)$-continuous (here

$\sigma(A,E)$-continuous (here ![]() $\delta_x\in C(X)^*$ is the Dirac delta evaluation functional at

$\delta_x\in C(X)^*$ is the Dirac delta evaluation functional at ![]() $x\in X$). Since for an Arens-regular Banach algebra, the bidual endowed with the unique Arens product is a dual Banach algebra, we may record the following lemma.

$x\in X$). Since for an Arens-regular Banach algebra, the bidual endowed with the unique Arens product is a dual Banach algebra, we may record the following lemma.

Lemma 2.1. Let A be a unital Arens-regular Banach algebra and let ![]() $i\colon A\to C(X)$ be an injective algebra homomorphism with dense range. Then

$i\colon A\to C(X)$ be an injective algebra homomorphism with dense range. Then ![]() $A^{**}$ shares with the maximal ideal space of

$A^{**}$ shares with the maximal ideal space of ![]() $C(X)^{**}$ densely many points.

$C(X)^{**}$ densely many points.

Proof. Since A is Arens-regular, ![]() $A^{**}$ is naturally a dual Banach algebra with the unique Arens product. Since

$A^{**}$ is naturally a dual Banach algebra with the unique Arens product. Since ![]() $i^{***}$ extends

$i^{***}$ extends ![]() $i^*$, for every

$i^*$, for every ![]() $x\in X$, we have

$x\in X$, we have ![]() $i^{***}(\delta_x) = i^*(\delta_x)\in A^*$, so that

$i^{***}(\delta_x) = i^*(\delta_x)\in A^*$, so that ![]() $i^*(\delta_x)$ is

$i^*(\delta_x)$ is ![]() $\sigma(A^{**}, A^*)$-continuous. It remains to invoke the fact that X can be identified with an open dense subset of the maximal ideal space of

$\sigma(A^{**}, A^*)$-continuous. It remains to invoke the fact that X can be identified with an open dense subset of the maximal ideal space of ![]() $C(X)^{**}$ via

$C(X)^{**}$ via ![]() $x\mapsto (\delta_x)^{**}=\delta_{\iota(x)}$ for some point

$x\mapsto (\delta_x)^{**}=\delta_{\iota(x)}$ for some point ![]() $\iota(x)$ in the maximal ideal space of

$\iota(x)$ in the maximal ideal space of ![]() $C(X)^{**}$ (see the discussion after [Reference Dales, Lau and Strauss12, definition 3.3]); the map ι is necessarily discontinuous unless X is finite).

$C(X)^{**}$ (see the discussion after [Reference Dales, Lau and Strauss12, definition 3.3]); the map ι is necessarily discontinuous unless X is finite).

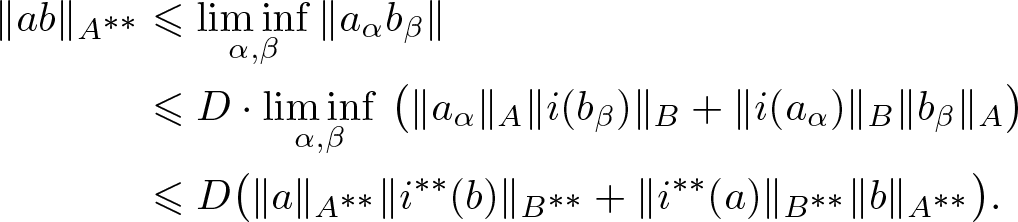

Let us record two permanence properties of differential embeddings; even though we shall not utilize (ii) in the present article, we keep it for possible future reference.

Lemma 2.2. Let A be a Banach algebra continuously embedded into another Banach algebra B by a homomorphism ![]() $i\colon A\to B$ as a differential subalgebra.

$i\colon A\to B$ as a differential subalgebra.

(i) Consider both in

$A^{**}$ and

$A^{**}$ and  $B^{**}$ either left or right Arens products. Then in either setting

$B^{**}$ either left or right Arens products. Then in either setting  $i^{**}\colon A^{**}\to B^{**}$ is a differential embedding.

$i^{**}\colon A^{**}\to B^{**}$ is a differential embedding.(ii) Let

$\mathscr{U}$ be an ultrafilter. Then

$\mathscr{U}$ be an ultrafilter. Then  $i^{\mathscr{U}}\colon A^{\mathscr{U}}\to B^{\mathscr{U}}$ is a differential embedding between the respective ultrapowers.

$i^{\mathscr{U}}\colon A^{\mathscr{U}}\to B^{\mathscr{U}}$ is a differential embedding between the respective ultrapowers.

Proof. Case 1. Let ![]() $\{a_{\alpha}\}, \{b_{\beta}\} \subset A$ be bounded nets

$\{a_{\alpha}\}, \{b_{\beta}\} \subset A$ be bounded nets ![]() $\sigma(A^{**}, A^*)$-convergent to

$\sigma(A^{**}, A^*)$-convergent to ![]() $a,b \in A^{**}$ respectively, satisfying for any

$a,b \in A^{**}$ respectively, satisfying for any ![]() $\alpha, \beta$ conditions

$\alpha, \beta$ conditions ![]() $\|a_{\alpha}\|_A \leqslant \|a\|_{A^{**}}$ and

$\|a_{\alpha}\|_A \leqslant \|a\|_{A^{**}}$ and ![]() $\|b_{\beta}\|_B \leqslant \|b\|_{B^{**}}$ (it is possible by the Goldstine and Krein–Šmulyan theorems). Then

$\|b_{\beta}\|_B \leqslant \|b\|_{B^{**}}$ (it is possible by the Goldstine and Krein–Šmulyan theorems). Then

\begin{align*}

\begin{split}

\|ab\|_{A^{**}} &\leqslant \liminf\limits_{\alpha, \beta} \|a_{\alpha} b_{\beta}\| \\

&\leqslant D \cdot \liminf\limits_{\alpha, \beta} \, \big(\|a_{\alpha}\|_A\|i(b_{\beta})\|_B+\|i(a_{\alpha})\|_B\|b_{\beta}\|_A\big) \\

&\leqslant D \big(\|a\|_{A^{**}}\|i^{**}(b)\|_{B^{**}}+\|i^{**}(a)\|_{B^{**}}\|b\|_{A^{**}}\big).

\end{split}

\end{align*}

\begin{align*}

\begin{split}

\|ab\|_{A^{**}} &\leqslant \liminf\limits_{\alpha, \beta} \|a_{\alpha} b_{\beta}\| \\

&\leqslant D \cdot \liminf\limits_{\alpha, \beta} \, \big(\|a_{\alpha}\|_A\|i(b_{\beta})\|_B+\|i(a_{\alpha})\|_B\|b_{\beta}\|_A\big) \\

&\leqslant D \big(\|a\|_{A^{**}}\|i^{**}(b)\|_{B^{**}}+\|i^{**}(a)\|_{B^{**}}\|b\|_{A^{**}}\big).

\end{split}

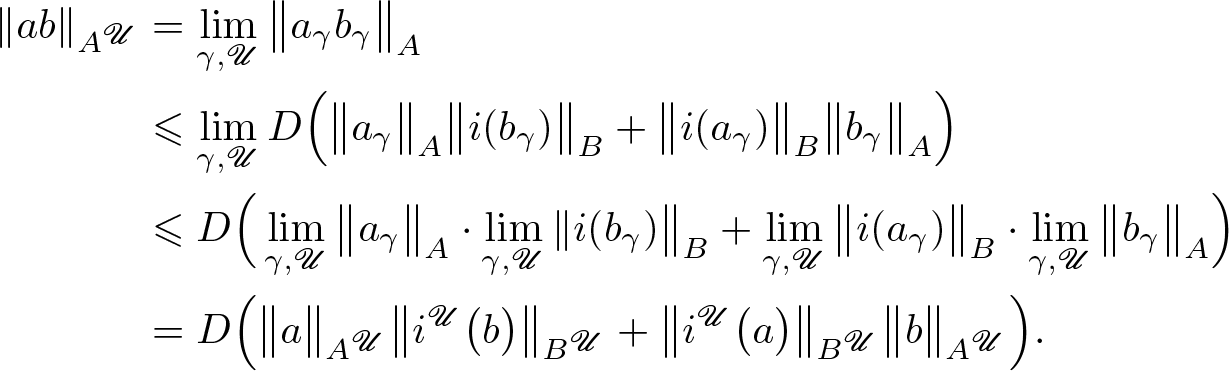

\end{align*} Case 2. Let ![]() $a=[(a_{\gamma})_{\gamma \in \Gamma}]$,

$a=[(a_{\gamma})_{\gamma \in \Gamma}]$, ![]() $b=[(b_{\gamma})_{\gamma \in \Gamma}] \in A^{\mathscr{U}}.$ Then

$b=[(b_{\gamma})_{\gamma \in \Gamma}] \in A^{\mathscr{U}}.$ Then

\begin{align*}

\begin{split}

\|a b \|_{A^{{\mathscr{U}}}} &= \lim_{\gamma, \mathscr{U}}\big\|a_{\gamma} b_{\gamma} \big\|_A \\

&\leqslant \lim_{\gamma, \mathscr{U}} D \Big(\big\|a_{\gamma}\big\|_A\big\|i(b_{\gamma})\big\|_B+\big\|i(a_{\gamma})\big\|_B\big\|b_{\gamma}\big\|_A\Big) \\

&\leqslant D \Big( \lim_{\gamma, \mathscr{U}} \big\|a_{\gamma}\big\|_A \cdot \lim_{\gamma, \mathscr{U}}\|i(b_{\gamma})\big\|_B+\lim_{\gamma, \mathscr{U}}\big\|i(a_{\gamma})\big\|_B\cdot \lim_{\gamma, \mathscr{U}}\big\|b_{\gamma}\big\|_A\Big) \\

&= D \Big(\big\|a\big\|_{A^{{\mathscr{U}}}}\big\|i^{{\mathscr{U}}}\big(b\big)\big\|_{B^{{\mathscr{U}}}}+\big\|i^{{\mathscr{{\mathscr{U}}}}}\big(a\big)\big\|_{B^{{\mathscr{U}}}}\big\|b\big\|_{A^{{\mathscr{U}}}}\Big).

\end{split}

\end{align*}

\begin{align*}

\begin{split}

\|a b \|_{A^{{\mathscr{U}}}} &= \lim_{\gamma, \mathscr{U}}\big\|a_{\gamma} b_{\gamma} \big\|_A \\

&\leqslant \lim_{\gamma, \mathscr{U}} D \Big(\big\|a_{\gamma}\big\|_A\big\|i(b_{\gamma})\big\|_B+\big\|i(a_{\gamma})\big\|_B\big\|b_{\gamma}\big\|_A\Big) \\

&\leqslant D \Big( \lim_{\gamma, \mathscr{U}} \big\|a_{\gamma}\big\|_A \cdot \lim_{\gamma, \mathscr{U}}\|i(b_{\gamma})\big\|_B+\lim_{\gamma, \mathscr{U}}\big\|i(a_{\gamma})\big\|_B\cdot \lim_{\gamma, \mathscr{U}}\big\|b_{\gamma}\big\|_A\Big) \\

&= D \Big(\big\|a\big\|_{A^{{\mathscr{U}}}}\big\|i^{{\mathscr{U}}}\big(b\big)\big\|_{B^{{\mathscr{U}}}}+\big\|i^{{\mathscr{{\mathscr{U}}}}}\big(a\big)\big\|_{B^{{\mathscr{U}}}}\big\|b\big\|_{A^{{\mathscr{U}}}}\Big).

\end{split}

\end{align*}2.2. Banach *-algebras

Let A be a unital Banach *-algebra. In this setting, for ![]() $a\in A$, we interpret

$a\in A$, we interpret ![]() $|a|^2$ as

$|a|^2$ as ![]() $a^*a$. We say that elements

$a^*a$. We say that elements ![]() $a,b$ in A are jointly non-degenerate, when

$a,b$ in A are jointly non-degenerate, when ![]() $|a|^2+|b|^2$ is invertible. When X is a compact space and

$|a|^2+|b|^2$ is invertible. When X is a compact space and ![]() $a,b \in C(X)$, we sometimes say that elements with

$a,b \in C(X)$, we sometimes say that elements with ![]() $|a|^2+|b|^2 \geqslant \eta$ (for some η > 0) are jointly η-non-degenerate. Let us introduce the following definition.

$|a|^2+|b|^2 \geqslant \eta$ (for some η > 0) are jointly η-non-degenerate. Let us introduce the following definition.

Definition 2.3. A unital Banach *-algebra A is approximable by jointly non-degenerate products whenever for all ![]() $a,b\in A$ and ɛ > 0 there exist jointly non-degenerate elements

$a,b\in A$ and ɛ > 0 there exist jointly non-degenerate elements ![]() $a^\prime, b^\prime\in A$ with

$a^\prime, b^\prime\in A$ with ![]() $\max \{\|a-a^\prime\|, \|b-b^\prime\| \} \lt \varepsilon$ such that

$\max \{\|a-a^\prime\|, \|b-b^\prime\| \} \lt \varepsilon$ such that ![]() $ab = a^\prime b^\prime$.

$ab = a^\prime b^\prime$.

Remark. It is readily seen that C(X) for a zero-dimensional compact space X has this property. Indeed, let ![]() $f,g\in C(X)$ and ɛ > 0. Consider the sets

$f,g\in C(X)$ and ɛ > 0. Consider the sets

•

$D_1 = \{x\in X\colon |f(x)|\geqslant \varepsilon/ 3\}$

$D_1 = \{x\in X\colon |f(x)|\geqslant \varepsilon/ 3\}$•

$D_2 = \{x\in X\colon |g(x)|\geqslant \varepsilon/ 3\}$

$D_2 = \{x\in X\colon |g(x)|\geqslant \varepsilon/ 3\}$•

$D_3 = \{x\in X\colon |f(x)|, |g(x)| \leqslant \varepsilon/2\}$.

$D_3 = \{x\in X\colon |f(x)|, |g(x)| \leqslant \varepsilon/2\}$.

Certainly, the sets ![]() $D_1, D_2, D_3$ are closed and cover the space X. As X is zero-dimensional, there exist pairwise clopen sets

$D_1, D_2, D_3$ are closed and cover the space X. As X is zero-dimensional, there exist pairwise clopen sets ![]() $D_1^\prime \subseteq D_1$,

$D_1^\prime \subseteq D_1$, ![]() $D_2^\prime \subseteq D_2$, and

$D_2^\prime \subseteq D_2$, and ![]() $D_3^\prime \subseteq D_3$ that still cover X, i.e.,

$D_3^\prime \subseteq D_3$ that still cover X, i.e., ![]() $X = D_1^\prime \cup D_2^\prime \cup D_3^\prime$. Let

$X = D_1^\prime \cup D_2^\prime \cup D_3^\prime$. Let  $f^\prime = f \cdot \mathbb{1}_{D_1^\prime\cup D_2^\prime} + \tfrac{\varepsilon}{2}\mathbb{1}_{D_3^\prime}$ and

$f^\prime = f \cdot \mathbb{1}_{D_1^\prime\cup D_2^\prime} + \tfrac{\varepsilon}{2}\mathbb{1}_{D_3^\prime}$ and  $g^\prime = g \cdot \mathbb{1}_{D_1^\prime\cup D_2^\prime} + \tfrac{2}{\varepsilon}fg\mathbb{1}_{D_3^\prime}$. Then f ʹ, g ʹ are the sought jointly non-degenerate approximants. On the other hand, as C(X) for

$g^\prime = g \cdot \mathbb{1}_{D_1^\prime\cup D_2^\prime} + \tfrac{2}{\varepsilon}fg\mathbb{1}_{D_3^\prime}$. Then f ʹ, g ʹ are the sought jointly non-degenerate approximants. On the other hand, as C(X) for ![]() $X = [0,1]$ and compact spaces alike are readily not approximable by jointly non-degenerate issues due to connectedness.

$X = [0,1]$ and compact spaces alike are readily not approximable by jointly non-degenerate issues due to connectedness.

Kowalczyk and Turowska [Reference Kowalczyk and Turowska26] showed that the algebra ![]() $BV[0,1]$ of functions of bounded variation on the unit interval is approximable by jointly non-degenerate products and Canarias, Karlovich, and Shargorodsky [Reference Canarias, Karlovich and Shargorodsky11] extended this result to algebras of bounded p-variation on the interval as well as certain further function algebras.

$BV[0,1]$ of functions of bounded variation on the unit interval is approximable by jointly non-degenerate products and Canarias, Karlovich, and Shargorodsky [Reference Canarias, Karlovich and Shargorodsky11] extended this result to algebras of bounded p-variation on the interval as well as certain further function algebras.

2.3. Ultraproducts

Ultraproducts of mathematical structures usually come in two main guises: the algebraic one (first-order) and the analytic one (second-order). Let us briefly summarize the link between these in the context of groups and their group algebras. This has been essentially developed by Daws in [Reference Daws14, §5.4] and further explained in [Reference Draga and Kania16, §2.3.2].

Let ![]() $(S_\gamma)_{\gamma\in \Gamma}$ be an infinite collection of semigroups and let

$(S_\gamma)_{\gamma\in \Gamma}$ be an infinite collection of semigroups and let ![]() $\mathscr U$ be an ultrafilter on Γ. The (algebraic) ultraproduct

$\mathscr U$ be an ultrafilter on Γ. The (algebraic) ultraproduct  $\prod_{\gamma\in \Gamma}^{\mathscr{U}}S_\gamma$ with respect to

$\prod_{\gamma\in \Gamma}^{\mathscr{U}}S_\gamma$ with respect to ![]() $\mathscr{U}$ (denoted

$\mathscr{U}$ (denoted ![]() $S^{\mathscr U}$ when

$S^{\mathscr U}$ when ![]() $S_\gamma=S$ for all

$S_\gamma=S$ for all ![]() $\gamma\in \Gamma$ and then termed the ultrapower of S with respect to

$\gamma\in \Gamma$ and then termed the ultrapower of S with respect to ![]() $\mathscr{U}$) is the quotient of the direct product

$\mathscr{U}$) is the quotient of the direct product  $\prod_{\gamma\in \Gamma}S_\gamma$ by the congruence

$\prod_{\gamma\in \Gamma}S_\gamma$ by the congruence

Then the just-defined ultraproduct is naturally a semigroup/group/Abelian group if Sγ are semigroups/groups/Abelian groups for ![]() $\gamma\in \Gamma$.

$\gamma\in \Gamma$.

Let ![]() $(A_\gamma)_{\gamma\in \Gamma}$ be an infinite collection of Banach spaces. Then the

$(A_\gamma)_{\gamma\in \Gamma}$ be an infinite collection of Banach spaces. Then the ![]() $\ell_\infty(\Gamma)$-direct sum

$\ell_\infty(\Gamma)$-direct sum  $A = ( \bigoplus_{\gamma\in \Gamma} A_\gamma)_{\ell_\infty(\Gamma)}$, that is, the space of all tuples

$A = ( \bigoplus_{\gamma\in \Gamma} A_\gamma)_{\ell_\infty(\Gamma)}$, that is, the space of all tuples ![]() $(x_\gamma)_{\gamma\in \Gamma}$ with

$(x_\gamma)_{\gamma\in \Gamma}$ with ![]() $x_\gamma\in A_\gamma$ (

$x_\gamma\in A_\gamma$ (![]() $\gamma\in \Gamma$) and

$\gamma\in \Gamma$) and ![]() $\sup_{\gamma\in \Gamma}\|x_\gamma\| \lt \infty$ is a Banach space under the supremum norm. Moreover, the subspace

$\sup_{\gamma\in \Gamma}\|x_\gamma\| \lt \infty$ is a Banach space under the supremum norm. Moreover, the subspace ![]() $J=c_0^{\mathscr U}(A_\gamma)_{\gamma\in \Gamma}$ comprising all tuples

$J=c_0^{\mathscr U}(A_\gamma)_{\gamma\in \Gamma}$ comprising all tuples ![]() $(x_\gamma)_{\gamma\in \Gamma}$ such that

$(x_\gamma)_{\gamma\in \Gamma}$ such that ![]() $\lim_{\gamma\to \mathscr{U}}\|x_\gamma\|=0$ is closed. The (Banach-space) ultraproduct

$\lim_{\gamma\to \mathscr{U}}\|x_\gamma\|=0$ is closed. The (Banach-space) ultraproduct  $\prod_{\gamma\in \Gamma}^{\mathscr U}A_\gamma$ of

$\prod_{\gamma\in \Gamma}^{\mathscr U}A_\gamma$ of ![]() $(A_\gamma)_{\gamma\in \Gamma}$ with respect to

$(A_\gamma)_{\gamma\in \Gamma}$ with respect to ![]() $\mathscr{U}$ is the quotient space

$\mathscr{U}$ is the quotient space ![]() $A / J$. If Aγ (

$A / J$. If Aγ (![]() $\gamma\in \Gamma$) are Banach algebras, then naturally so is A and J is then a closed ideal therein. Consequently, the ultraproduct is a Banach algebra. Let us record formally a link between these two constructions.

$\gamma\in \Gamma$) are Banach algebras, then naturally so is A and J is then a closed ideal therein. Consequently, the ultraproduct is a Banach algebra. Let us record formally a link between these two constructions.

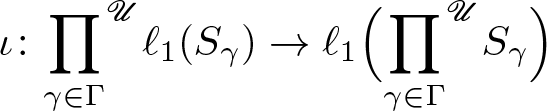

Lemma 2.5. Let ![]() $(S_\gamma)_{\gamma\in \Gamma}$ be an infinite collection of semigroups and let

$(S_\gamma)_{\gamma\in \Gamma}$ be an infinite collection of semigroups and let ![]() $\mathscr{U}$ be a countably incomplete ultrafilter on Γ. Then there exists a unique contractive homomorphism

$\mathscr{U}$ be a countably incomplete ultrafilter on Γ. Then there exists a unique contractive homomorphism

\begin{align}

\iota \colon {\prod_{\gamma\in \Gamma}}^{\mathscr{U}}\ell_1(S_\gamma)\to \ell_1\Big({\prod_{\gamma\in \Gamma}}^{\mathscr{U}}S_\gamma \Big)

\end{align}

\begin{align}

\iota \colon {\prod_{\gamma\in \Gamma}}^{\mathscr{U}}\ell_1(S_\gamma)\to \ell_1\Big({\prod_{\gamma\in \Gamma}}^{\mathscr{U}}S_\gamma \Big)

\end{align}that satisfies

\begin{align*}

\iota\Big(\big[(e_{g_\gamma})_{\gamma\in\Gamma}\big]\Big) = e_{[(g_\gamma)_{\gamma\in\Gamma}]}\qquad \Big(\big[(e_{g_\gamma})_{\gamma\in\Gamma}\big]\in {\prod_{\gamma\in \Gamma}}^{\mathscr U}\ell_1(S_\gamma)\Big).

\end{align*}

\begin{align*}

\iota\Big(\big[(e_{g_\gamma})_{\gamma\in\Gamma}\big]\Big) = e_{[(g_\gamma)_{\gamma\in\Gamma}]}\qquad \Big(\big[(e_{g_\gamma})_{\gamma\in\Gamma}\big]\in {\prod_{\gamma\in \Gamma}}^{\mathscr U}\ell_1(S_\gamma)\Big).

\end{align*}2.4. Abelian groups

Let G be a group. For ![]() $g\in G$, we denote by o(g) the order of the element g. For a (locally compact) Abelian group G, we denote by

$g\in G$, we denote by o(g) the order of the element g. For a (locally compact) Abelian group G, we denote by ![]() $\widehat{G}$ the Pontryagin dual group of G; for details and basic properties concerning this duality, we refer to [Reference Hewitt and Ross23, chapter 6].

$\widehat{G}$ the Pontryagin dual group of G; for details and basic properties concerning this duality, we refer to [Reference Hewitt and Ross23, chapter 6].

If G is an (Abelian) divisible group, that is, for any ![]() $g\in G$ and

$g\in G$ and ![]() $n\in \mathbb N$ there is

$n\in \mathbb N$ there is ![]() $h\in G$ such that g = nh, then G is an injective object in the category Abelian groups, which means that for any Abelian groups

$h\in G$ such that g = nh, then G is an injective object in the category Abelian groups, which means that for any Abelian groups ![]() $H_1 \subset H_2$, every homomorphism

$H_1 \subset H_2$, every homomorphism ![]() $\varphi\colon H_1\to G$ extends to a homomorphism

$\varphi\colon H_1\to G$ extends to a homomorphism ![]() $\overline{\varphi}\colon H_2\to G$. Direct sums of arbitrary many copies of

$\overline{\varphi}\colon H_2\to G$. Direct sums of arbitrary many copies of ![]() $\mathbb Q$, the additive group of rationals, are divisible.

$\mathbb Q$, the additive group of rationals, are divisible.

Let us record for the future reference the following observation, likely well known to algebraically oriented model theorists.

Lemma 2.6. Suppose that G is an Abelian group with ![]() $\sup_{g\in G} o(g) = \infty$. Then

$\sup_{g\in G} o(g) = \infty$. Then ![]() $\mathbb Z^{(\mathbb R)}$ embeds into an ultrapower of G with respect to an ultrafilter on a countable set.

$\mathbb Z^{(\mathbb R)}$ embeds into an ultrapower of G with respect to an ultrafilter on a countable set.

Proof. Let ![]() $\mathscr{U}$ be a non-principal ultrafilter on

$\mathscr{U}$ be a non-principal ultrafilter on ![]() $\mathbb N$ and let

$\mathbb N$ and let ![]() $(g_n)_{n=1}^\infty$ be a sequence in G such that

$(g_n)_{n=1}^\infty$ be a sequence in G such that ![]() $\sup_{n}o(g_n) = \infty$. Then

$\sup_{n}o(g_n) = \infty$. Then ![]() $g = [(g_n)_{n=1}^\infty ]$ has infinite order in

$g = [(g_n)_{n=1}^\infty ]$ has infinite order in ![]() $H = G^{\mathscr{U}}$. Let

$H = G^{\mathscr{U}}$. Let ![]() $\mathscr{A}$ be an almost disjoint family of infinite subsets of

$\mathscr{A}$ be an almost disjoint family of infinite subsets of ![]() $\mathbb N$ that has cardinality continuum. Then all but at most one elements

$\mathbb N$ that has cardinality continuum. Then all but at most one elements ![]() $\mathscr{A}$ are not in

$\mathscr{A}$ are not in ![]() $\mathscr{U}$ (as

$\mathscr{U}$ (as ![]() $\mathscr{U}$ is non-principal and closed under finite intersections), so let us assume that

$\mathscr{U}$ is non-principal and closed under finite intersections), so let us assume that ![]() $\mathscr{A} \subset \mathscr{U}^\prime$. For each

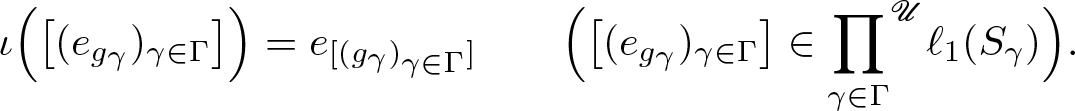

$\mathscr{A} \subset \mathscr{U}^\prime$. For each ![]() $A\in \mathscr{A}$, we set

$A\in \mathscr{A}$, we set

\begin{align*}

g_A(i) =

\left\{\begin{array}{ll}

g, & i \notin A, \\

0, & i \in A

\end{array}

\quad (i\in \mathbb N). \right.

\end{align*}

\begin{align*}

g_A(i) =

\left\{\begin{array}{ll}

g, & i \notin A, \\

0, & i \in A

\end{array}

\quad (i\in \mathbb N). \right.

\end{align*} Then ![]() $h_A = [(g_A(i))_{i=1}^\infty] \in H^{\mathscr{U}}$ and

$h_A = [(g_A(i))_{i=1}^\infty] \in H^{\mathscr{U}}$ and ![]() $o(h_A) = \infty$ (

$o(h_A) = \infty$ (![]() $A\in \mathscr{A}$). Moreover,

$A\in \mathscr{A}$). Moreover, ![]() $\{h_A\colon A\in \mathscr A\}$ is a

$\{h_A\colon A\in \mathscr A\}$ is a ![]() $\mathbb Z$-linearly independent set of cardinality continuum. As such, the subgroup it generates is isomorphic to

$\mathbb Z$-linearly independent set of cardinality continuum. As such, the subgroup it generates is isomorphic to ![]() $\mathbb Z^{(\mathbb R)}$. It remains to notice that canonically

$\mathbb Z^{(\mathbb R)}$. It remains to notice that canonically ![]() $(G^{\mathscr{U}})^{\mathscr U} \cong G^{\mathscr{U} \otimes \mathscr{U}}$, as required.

$(G^{\mathscr{U}})^{\mathscr U} \cong G^{\mathscr{U} \otimes \mathscr{U}}$, as required.

2.5. Semigroup algebras

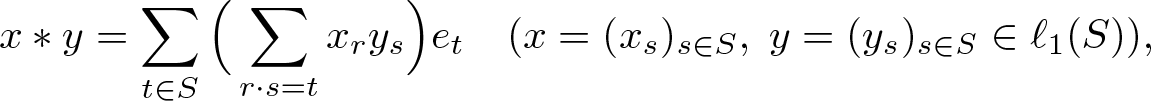

Let S be a semigroup written multiplicatively. In the Banach space ![]() $\ell_1(S)$, one can define a convolution product by

$\ell_1(S)$, one can define a convolution product by

\begin{align*}

x\ast y =\sum_{t\in S} \Big(\sum_{r\cdot s=t}x_r y_s\Big)e_t \quad (x = (x_s)_{s\in S},\; y = (y_s)_{s\in S}\in \ell_1(S)),

\end{align*}

\begin{align*}

x\ast y =\sum_{t\in S} \Big(\sum_{r\cdot s=t}x_r y_s\Big)e_t \quad (x = (x_s)_{s\in S},\; y = (y_s)_{s\in S}\in \ell_1(S)),

\end{align*} where ![]() $(e_s)_{s\in S}$ is the canonical unit vector basis of

$(e_s)_{s\in S}$ is the canonical unit vector basis of ![]() $\ell_1(S)$, together with

$\ell_1(S)$, together with ![]() $\ell_1(S)$ becomes a Banach algebra. For the additive semigroup of natural numbers, the convolution in

$\ell_1(S)$ becomes a Banach algebra. For the additive semigroup of natural numbers, the convolution in ![]() $\ell_1(\mathbb N)$ renders the familiar Cauchy product.

$\ell_1(\mathbb N)$ renders the familiar Cauchy product.

Suppose that ![]() $T\subseteq S$ is a subsemigroup. Then

$T\subseteq S$ is a subsemigroup. Then ![]() $\ell_1(T)$ is naturally a closed subspace of

$\ell_1(T)$ is naturally a closed subspace of ![]() $\ell_1(S)$, which is moreover a closed subalgebra. Every surjective semigroup homomorphism

$\ell_1(S)$, which is moreover a closed subalgebra. Every surjective semigroup homomorphism ![]() $\vartheta\colon T\to S$ implements a surjective homomorphism

$\vartheta\colon T\to S$ implements a surjective homomorphism ![]() $\iota_\vartheta\colon \ell_1(T)\to \ell_1(S)$ on the Banach-algebra level by the action

$\iota_\vartheta\colon \ell_1(T)\to \ell_1(S)$ on the Banach-algebra level by the action

When G is an Abelian (discrete) group, then the (compact) dual group ![]() $\widehat{G}$ is the maximal ideal space of the convolution algebra

$\widehat{G}$ is the maximal ideal space of the convolution algebra ![]() $\ell_1(G)$. More information on semigroup algebras may be found in [Reference Dales, Lau and Strauss12, chapter 4].

$\ell_1(G)$. More information on semigroup algebras may be found in [Reference Dales, Lau and Strauss12, chapter 4].

3. Proofs of theorems A and B

The proof of Theorem 1.2 relies on constructing certain approximation scheme for pairs of elements, an idea that shares similarities with the methods used in the main results of [Reference Kowalczyk and Turowska26] and [Reference Canarias, Karlovich and Shargorodsky11]. However, the results achieved in Theorem 1.2 are more general, and the techniques applied in its proof are correspondingly broader. Let us now proceed to the proof.

Proof of Theorem 1.2

Suppose that A has norm-controlled inversion implemented by a *-homomorphism ![]() $i\colon A\to C(X)$. Since *-homomorphism of Banach *-algebra into a C*-algebra is always norm decreasing, we have

$i\colon A\to C(X)$. Since *-homomorphism of Banach *-algebra into a C*-algebra is always norm decreasing, we have

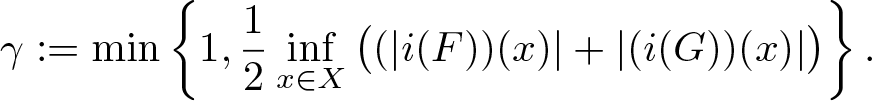

Suppose that ![]() $F,G\in A$ are jointly non-degenerate (in particular,

$F,G\in A$ are jointly non-degenerate (in particular, ![]() $|F| + |G|$ is invertible in C(X) being nowhere zero). Fix

$|F| + |G|$ is invertible in C(X) being nowhere zero). Fix ![]() $\varepsilon\in(0,1)$ and let

$\varepsilon\in(0,1)$ and let

\begin{align}

\gamma:=\min\left\{1,\frac{1}{2}\inf_{x\in X}

\big((|i(F))(x)|+|(i(G))(x)|\big)\right\}.

\end{align}

\begin{align}

\gamma:=\min\left\{1,\frac{1}{2}\inf_{x\in X}

\big((|i(F))(x)|+|(i(G))(x)|\big)\right\}.

\end{align}Set

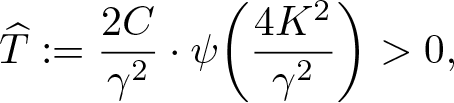

\begin{align}

\widehat{T}:= \frac{2C}{{\gamma}^2} \cdot \psi\bigg( \frac{4K^2}{{\gamma}^2}\bigg) \gt 0,

\end{align}

\begin{align}

\widehat{T}:= \frac{2C}{{\gamma}^2} \cdot \psi\bigg( \frac{4K^2}{{\gamma}^2}\bigg) \gt 0,

\end{align} where the function ψ satisfies (1.1). Moreover, let  $ T:= \max \{\widehat{T}, 1\}.$ Pick an arbitrary element

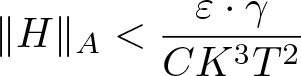

$ T:= \max \{\widehat{T}, 1\}.$ Pick an arbitrary element ![]() $H\in A$ so that

$H\in A$ so that

\begin{align}

\|H\|_{A} \lt \frac{\varepsilon \cdot \gamma}{C K^3 T^2}

\end{align}

\begin{align}

\|H\|_{A} \lt \frac{\varepsilon \cdot \gamma}{C K^3 T^2}

\end{align}and consider

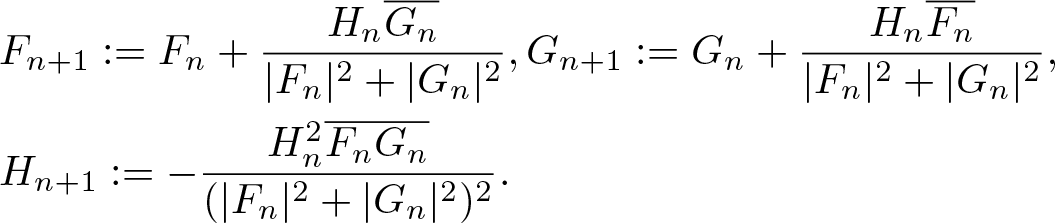

We then define recursively the sequences ![]() $(F_n)_{n=0}^\infty$,

$(F_n)_{n=0}^\infty$, ![]() $(G_n)_{n=0}^\infty$, and

$(G_n)_{n=0}^\infty$, and ![]() $(H_n)_{n=0}^\infty$ by

$(H_n)_{n=0}^\infty$ by

\begin{align}

& F_{n+1} := F_n+\frac{H_n\overline{G_n}}{|F_n|^2+|G_n|^2}, G_{n+1} := G_n+\frac{H_n\overline{F_n}}{|F_n|^2+|G_n|^2},\nonumber\\

& H_{n+1} :=-\frac{H_n^2\overline{F_n G_n}}{(|F_n|^2+|G_n|^2)^2}.

\end{align}

\begin{align}

& F_{n+1} := F_n+\frac{H_n\overline{G_n}}{|F_n|^2+|G_n|^2}, G_{n+1} := G_n+\frac{H_n\overline{F_n}}{|F_n|^2+|G_n|^2},\nonumber\\

& H_{n+1} :=-\frac{H_n^2\overline{F_n G_n}}{(|F_n|^2+|G_n|^2)^2}.

\end{align}We claim that

(i)

\begin{align*}

F_nG_n+H_n=FG+H\quad (n = 0, 1, 2, \ldots),

\end{align*}

\begin{align*}

F_nG_n+H_n=FG+H\quad (n = 0, 1, 2, \ldots),

\end{align*}(ii)

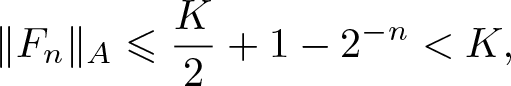

\begin{align*}

\|F_n\|_{A}, \|G_n\|_{A}\leqslant \tfrac{1}{2}K+1-2^{-n} \lt K,

\end{align*}

\begin{align*}

\|F_n\|_{A}, \|G_n\|_{A}\leqslant \tfrac{1}{2}K+1-2^{-n} \lt K,

\end{align*}(iii)

\begin{align*}

\inf_{x\in X}\big(|(i(F_n))(x)|+|(i(G_n))(x)|\big)\geqslant \gamma +\gamma\cdot 2^{-n} \gt 0,

\end{align*}

\begin{align*}

\inf_{x\in X}\big(|(i(F_n))(x)|+|(i(G_n))(x)|\big)\geqslant \gamma +\gamma\cdot 2^{-n} \gt 0,

\end{align*}(iv)

\begin{align*}

\|H_n\|_{A}\leqslant \frac{1}{2^n}\cdot\frac{\varepsilon \cdot \gamma}{C K^3 T^2}.

\end{align*}

\begin{align*}

\|H_n\|_{A}\leqslant \frac{1}{2^n}\cdot\frac{\varepsilon \cdot \gamma}{C K^3 T^2}.

\end{align*}

Note that (iii) implies that sequences (3.7) are well-defined. We will prove these claims by induction.

It follows from (3.6) that ![]() $F_0G_0+H_0=FG+H.$ We obtain from (3.2)–(3.6) that

$F_0G_0+H_0=FG+H.$ We obtain from (3.2)–(3.6) that

•

$ \|F_0\|_{A}=\|F\|_{A}\leqslant K/2$,

$ \|F_0\|_{A}=\|F\|_{A}\leqslant K/2$,•

$\|G_0\|_{A}=\|G\|_{A}\leqslant K/2$,

$\|G_0\|_{A}=\|G\|_{A}\leqslant K/2$,•

$\|H_0\|_{A}=\|H\|_{A} \lt \frac{\varepsilon \cdot \gamma}{CK^3T^2}$,

$\|H_0\|_{A}=\|H\|_{A} \lt \frac{\varepsilon \cdot \gamma}{CK^3T^2}$,•

$\inf_{x\in X}\big(|F_0(x)|+|G_0(x)|\big) =

\inf_{x\in X}\big(|F(x)|+|G(x)|\big)\geqslant 2\gamma \gt 0.$

$\inf_{x\in X}\big(|F_0(x)|+|G_0(x)|\big) =

\inf_{x\in X}\big(|F(x)|+|G(x)|\big)\geqslant 2\gamma \gt 0.$

That is, (i)–(iv) are satisfied for n = 0.

Now we assume that (i)–(iv) are fulfilled for some ![]() $n = 0, 1,2, \ldots $. Consequently, sequences (3.7) are well-defined. Then, taking into account (3.3), we see that

$n = 0, 1,2, \ldots $. Consequently, sequences (3.7) are well-defined. Then, taking into account (3.3), we see that ![]() $K/2\geqslant 1$ and

$K/2\geqslant 1$ and

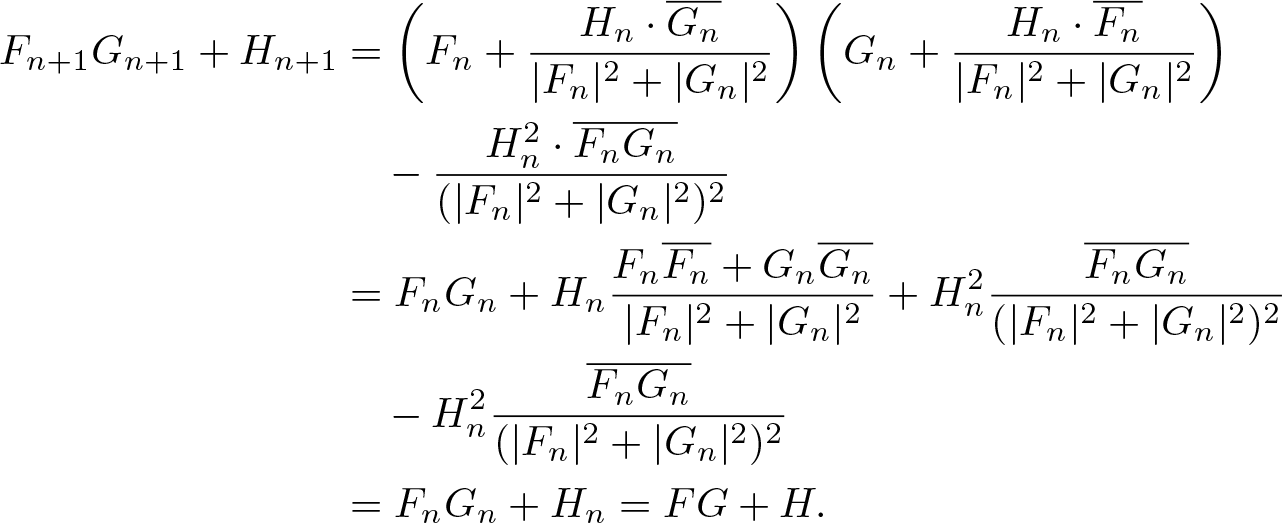

\begin{align}

\|F_n\|_{A}\leqslant \frac{K}{2}+1-2^{-n} \lt K,

\end{align}

\begin{align}

\|F_n\|_{A}\leqslant \frac{K}{2}+1-2^{-n} \lt K,

\end{align} \begin{align}

\|G_n\|_{A}\leqslant \frac{K}{2}+1-2^{-n} \lt K,

\end{align}

\begin{align}

\|G_n\|_{A}\leqslant \frac{K}{2}+1-2^{-n} \lt K,

\end{align} \begin{align}

\inf_{x\in X}\big(|(i(F_n))(x)|+|(i(G_n))(x)|\big)\geqslant \gamma+\gamma\cdot 2^{-n} \gt \gamma,

\end{align}

\begin{align}

\inf_{x\in X}\big(|(i(F_n))(x)|+|(i(G_n))(x)|\big)\geqslant \gamma+\gamma\cdot 2^{-n} \gt \gamma,

\end{align} \begin{align}

\|H_n\|_{A}\leqslant \varepsilon\cdot 2^{-n}\cdot\frac{\gamma}{CK^3T^2}.

\end{align}

\begin{align}

\|H_n\|_{A}\leqslant \varepsilon\cdot 2^{-n}\cdot\frac{\gamma}{CK^3T^2}.

\end{align}Let us show that (i)–(iv) are fulfilled for n + 1.

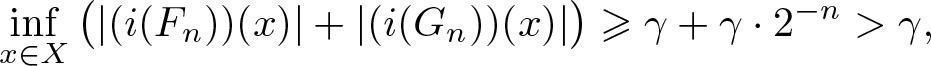

For (i), it follows from (3.7)–(3.8) that

\begin{align*}

\begin{aligned}

F_{n+1}G_{n+1}+H_{n+1}

&=

\left(F_n+\frac{H_n\cdot\overline{G_n}}{|F_n|^2+|G_n|^2}\right)

\left(G_n+\frac{H_n\cdot\overline{F_n}}{|F_n|^2+|G_n|^2}\right)\\

& \quad -

\frac{H_n^2\cdot\overline{F_nG_n}}{(|F_n|^2+|G_n|^2)^2}

\\

&=

F_nG_n+H_n\frac{F_n\overline{F_n}+G_n\overline{G_n}}{|F_n|^2+|G_n|^2}

+

H_n^2\frac{\overline{F_nG_n}}{(|F_n|^2+|G_n|^2)^2}\\

& \quad -

H_n^2\frac{\overline{F_nG_n}}{(|F_n|^2+|G_n|^2)^2}

\\

&=

F_nG_n+H_n=FG+H.

\end{aligned}

\end{align*}

\begin{align*}

\begin{aligned}

F_{n+1}G_{n+1}+H_{n+1}

&=

\left(F_n+\frac{H_n\cdot\overline{G_n}}{|F_n|^2+|G_n|^2}\right)

\left(G_n+\frac{H_n\cdot\overline{F_n}}{|F_n|^2+|G_n|^2}\right)\\

& \quad -

\frac{H_n^2\cdot\overline{F_nG_n}}{(|F_n|^2+|G_n|^2)^2}

\\

&=

F_nG_n+H_n\frac{F_n\overline{F_n}+G_n\overline{G_n}}{|F_n|^2+|G_n|^2}

+

H_n^2\frac{\overline{F_nG_n}}{(|F_n|^2+|G_n|^2)^2}\\

& \quad -

H_n^2\frac{\overline{F_nG_n}}{(|F_n|^2+|G_n|^2)^2}

\\

&=

F_nG_n+H_n=FG+H.

\end{aligned}

\end{align*}Hence, (i) is satisfied for n + 1.

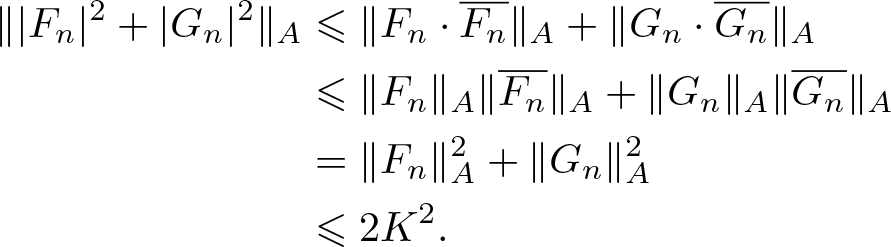

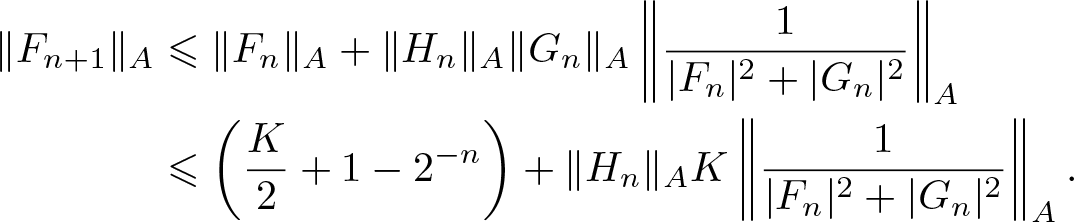

As for (ii), using (3.9)–(3.10), we conclude that

\begin{align}

\| |F_n|^2+|G_n|^2\|_{A}

&\leqslant

\|F_n\cdot \overline{F_n}\|_{A}

+

\|G_n\cdot\overline{G_n}\|_{A} \nonumber\\

&\leqslant

\| F_n\|_{A}

\|\overline{F_n}\|_{A}

+

\|G_n\|_{A}\|\overline{G_n}\|_{A}\nonumber\\

&=

\|F_n\|_{A}^2 +\|G_n\|_{A}^2\nonumber\\

&\leqslant

2K^2.

\end{align}

\begin{align}

\| |F_n|^2+|G_n|^2\|_{A}

&\leqslant

\|F_n\cdot \overline{F_n}\|_{A}

+

\|G_n\cdot\overline{G_n}\|_{A} \nonumber\\

&\leqslant

\| F_n\|_{A}

\|\overline{F_n}\|_{A}

+

\|G_n\|_{A}\|\overline{G_n}\|_{A}\nonumber\\

&=

\|F_n\|_{A}^2 +\|G_n\|_{A}^2\nonumber\\

&\leqslant

2K^2.

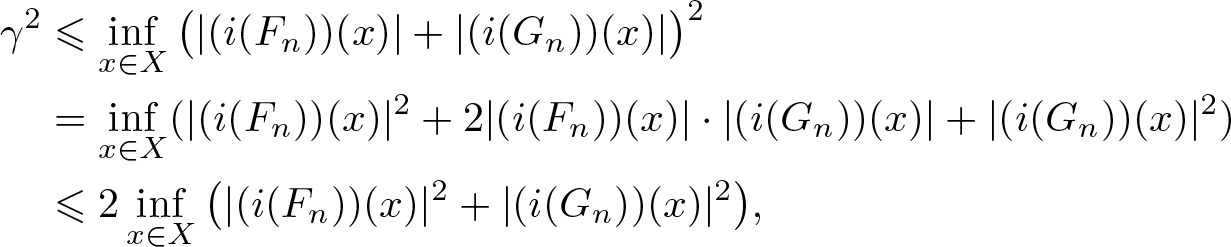

\end{align}It follows from (3.11) that

\begin{align*}

\gamma^2 & \leqslant \inf\limits_{x\in X}\big(|(i(F_n))(x)|+|(i(G_n))(x)|\big)^2\\

& = \inf\limits_{x\in X} ( |(i(F_n))(x)|^2+2|(i(F_n))(x)|\cdot|(i(G_n))(x)|+|(i(G_n))(x)|^2) \\

& \leqslant

2\inf\limits_{x\in X}\big(|(i(F_n))(x)|^2+|(i(G_n))(x)|^2\big),

\end{align*}

\begin{align*}

\gamma^2 & \leqslant \inf\limits_{x\in X}\big(|(i(F_n))(x)|+|(i(G_n))(x)|\big)^2\\

& = \inf\limits_{x\in X} ( |(i(F_n))(x)|^2+2|(i(F_n))(x)|\cdot|(i(G_n))(x)|+|(i(G_n))(x)|^2) \\

& \leqslant

2\inf\limits_{x\in X}\big(|(i(F_n))(x)|^2+|(i(G_n))(x)|^2\big),

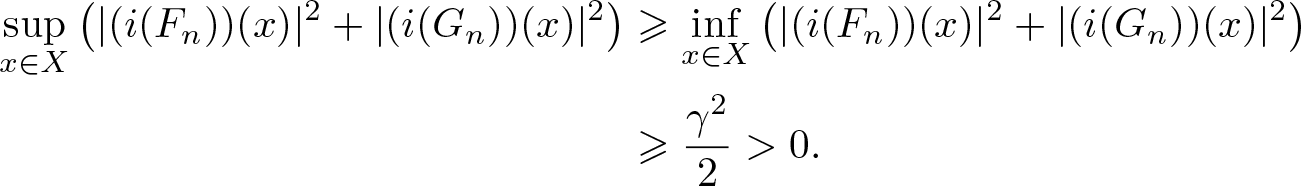

\end{align*}hence

\begin{align}

\sup_{x\in X}\big(|(i(F_n))(x)|^2+|(i(G_n))(x)|^2\big) & \geqslant \inf_{x\in X}\big(|(i(F_n))(x)|^2+|(i(G_n))(x)|^2\big) \nonumber\\

& \geqslant \frac{\gamma^2}{2} \gt 0.

\end{align}

\begin{align}

\sup_{x\in X}\big(|(i(F_n))(x)|^2+|(i(G_n))(x)|^2\big) & \geqslant \inf_{x\in X}\big(|(i(F_n))(x)|^2+|(i(G_n))(x)|^2\big) \nonumber\\

& \geqslant \frac{\gamma^2}{2} \gt 0.

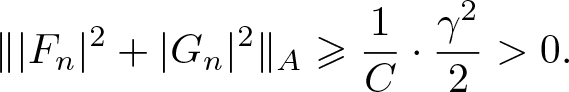

\end{align}By (3.1) and (3.14), we obtain

\begin{align}

\| |F_n|^2+|G_n|^2\|_{A} \geqslant \frac{1}{C} \cdot \frac{\gamma^2}{2} \gt 0.

\end{align}

\begin{align}

\| |F_n|^2+|G_n|^2\|_{A} \geqslant \frac{1}{C} \cdot \frac{\gamma^2}{2} \gt 0.

\end{align}It then follows from (3.7), (3.9)–(3.10), and (3.14) that

\begin{align}

\begin{split}

\|F_{n+1}\|_{A}

&\leqslant

\|F_n\|_{A}+\|H_n\|_{A}\|G_n\|_{A}

\left\|\frac{1}{|F_n|^2+|G_n|^2}\right\|_{A}\\

&\leqslant

\left(\frac{K}{2}+1-2^{-n}\right)+\|H_n\|_{A}K

\left\|\frac{1}{|F_n|^2+|G_n|^2}\right\|_{A}.

\end{split}

\end{align}

\begin{align}

\begin{split}

\|F_{n+1}\|_{A}

&\leqslant

\|F_n\|_{A}+\|H_n\|_{A}\|G_n\|_{A}

\left\|\frac{1}{|F_n|^2+|G_n|^2}\right\|_{A}\\

&\leqslant

\left(\frac{K}{2}+1-2^{-n}\right)+\|H_n\|_{A}K

\left\|\frac{1}{|F_n|^2+|G_n|^2}\right\|_{A}.

\end{split}

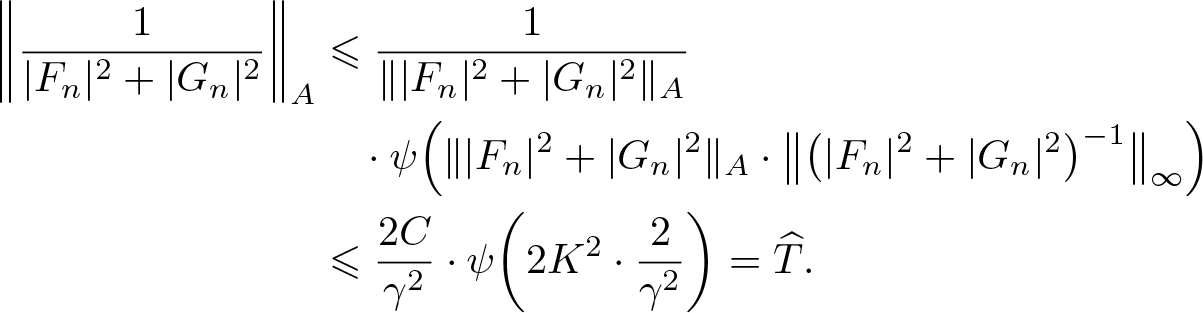

\end{align}Since A admits norm-controlled inversion in C(X), we follows from (3.13), (3.14), (3.15) that

\begin{align}

\begin{split}

\left\|\frac{1}{|F_n|^2+|G_n|^2}\right\|_A

&\leqslant \frac{1}{\||F_n|^2+|G_n|^2\|_A}\\

& \quad \cdot \psi\Big({\||F_n|^2+|G_n|^2\|_A

\cdot \big\|\big(|F_n|^2+|G_n|^2\big)^{-1}\big\|_{\infty}}\Big) \\

&\leqslant \frac{2C}{{\gamma}^2}

\cdot \psi\bigg({2K^2

\cdot \frac{2}{\gamma^2}}\bigg)= \widehat{T}.

\end{split}

\end{align}

\begin{align}

\begin{split}

\left\|\frac{1}{|F_n|^2+|G_n|^2}\right\|_A

&\leqslant \frac{1}{\||F_n|^2+|G_n|^2\|_A}\\

& \quad \cdot \psi\Big({\||F_n|^2+|G_n|^2\|_A

\cdot \big\|\big(|F_n|^2+|G_n|^2\big)^{-1}\big\|_{\infty}}\Big) \\

&\leqslant \frac{2C}{{\gamma}^2}

\cdot \psi\bigg({2K^2

\cdot \frac{2}{\gamma^2}}\bigg)= \widehat{T}.

\end{split}

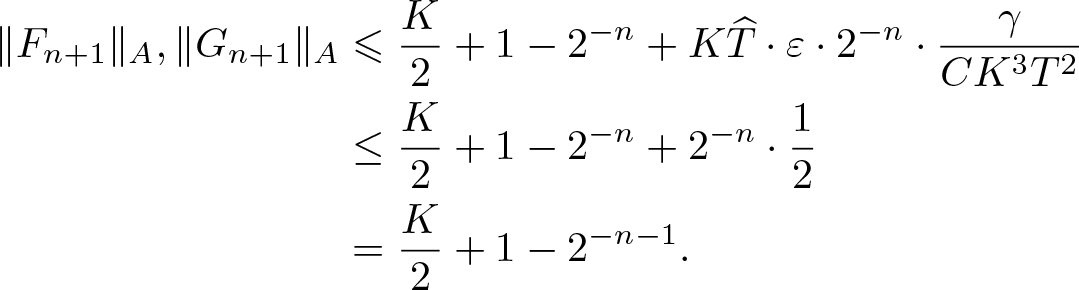

\end{align} Combining (3.16)–(3.17) with (3.12) and taking into account that ![]() $\varepsilon \in(0,1),$

$\varepsilon \in(0,1),$ ![]() $\gamma \in(0,1],$

$\gamma \in(0,1],$ ![]() $ K \geqslant 2,$

$ K \geqslant 2,$ ![]() $C\geqslant 1$, and

$C\geqslant 1$, and ![]() $T\geqslant 1$, we obtain

$T\geqslant 1$, we obtain

\begin{align}

\|F_{n+1}\|_{A}, \|G_{n+1}\|_{A}

&\leqslant

\frac{K}{2}+1-2^{-n}+ K \widehat{T} \cdot\varepsilon\cdot 2^{-n}\cdot\frac{\gamma}{CK^3T^2}\nonumber\\

&\leq

\frac{K}{2}+1-2^{-n}+2^{-n} \cdot \frac{1}{2}\nonumber\\

& = \frac{K}{2}+1-2^{-n-1}.

\end{align}

\begin{align}

\|F_{n+1}\|_{A}, \|G_{n+1}\|_{A}

&\leqslant

\frac{K}{2}+1-2^{-n}+ K \widehat{T} \cdot\varepsilon\cdot 2^{-n}\cdot\frac{\gamma}{CK^3T^2}\nonumber\\

&\leq

\frac{K}{2}+1-2^{-n}+2^{-n} \cdot \frac{1}{2}\nonumber\\

& = \frac{K}{2}+1-2^{-n-1}.

\end{align}Thus, (ii) is fulfilled for n + 1.

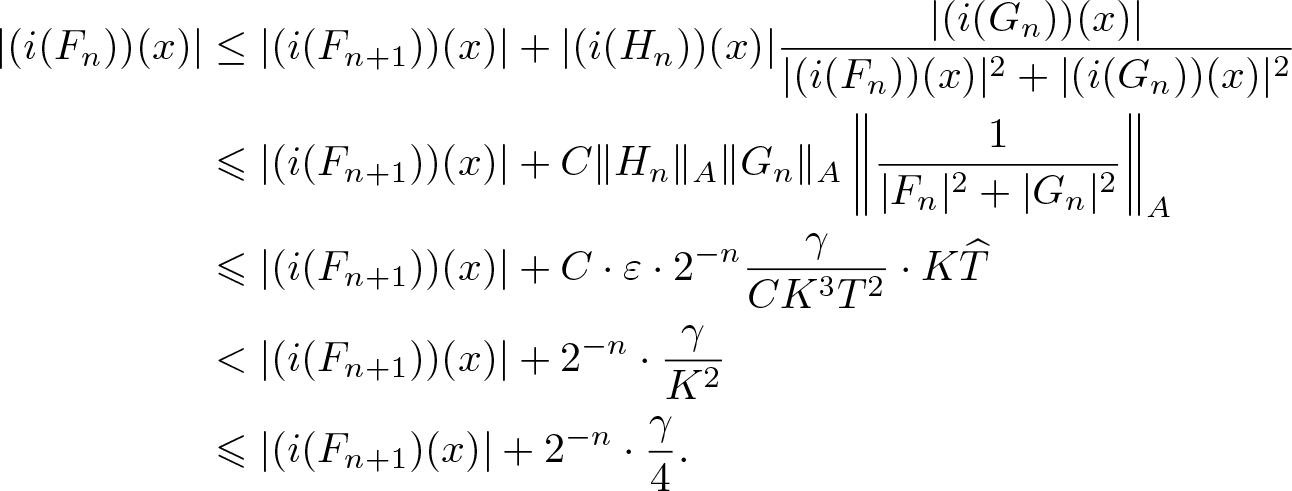

In order to verify (iii), since ![]() $\varepsilon \in(0,1),$

$\varepsilon \in(0,1),$ ![]() $\gamma \in(0,1],$

$\gamma \in(0,1],$ ![]() $K \geqslant 2,$

$K \geqslant 2,$ ![]() $C\geqslant 1$, and

$C\geqslant 1$, and ![]() $T\geqslant 1$, it follows from (3.7), (3.1), (3.10), (3.12), and (3.17) that for

$T\geqslant 1$, it follows from (3.7), (3.1), (3.10), (3.12), and (3.17) that for ![]() $x\in X$ we have

$x\in X$ we have

\begin{align*}

\begin{split}

|(i(F_n))(x)|

&\leq

|(i(F_{n+1}))(x)|+|(i(H_n))(x)|\frac{|(i(G_n))(x)|}{|(i(F_n))(x)|^2+|(i(G_n))(x)|^2}\\

&\leqslant

|(i(F_{n+1}))(x)|+ C\|H_n\|_A\|G_n\|_A

\left\|\frac{1}{|F_n|^2+|G_n|^2}\right\|_A

\\

&\leqslant

|(i(F_{n+1}))(x)|+

C \cdot \varepsilon\cdot 2^{-n}\frac{\gamma}{CK^3T^2}\cdot K\widehat{T}\\

& \lt |(i(F_{n+1}))(x)|+2^{-n}\cdot\frac{\gamma}{K^2}\\

&\leqslant

|(i(F_{n+1})(x)|+2^{-n}\cdot\frac{\gamma}{4}.

\end{split}

\end{align*}

\begin{align*}

\begin{split}

|(i(F_n))(x)|

&\leq

|(i(F_{n+1}))(x)|+|(i(H_n))(x)|\frac{|(i(G_n))(x)|}{|(i(F_n))(x)|^2+|(i(G_n))(x)|^2}\\

&\leqslant

|(i(F_{n+1}))(x)|+ C\|H_n\|_A\|G_n\|_A

\left\|\frac{1}{|F_n|^2+|G_n|^2}\right\|_A

\\

&\leqslant

|(i(F_{n+1}))(x)|+

C \cdot \varepsilon\cdot 2^{-n}\frac{\gamma}{CK^3T^2}\cdot K\widehat{T}\\

& \lt |(i(F_{n+1}))(x)|+2^{-n}\cdot\frac{\gamma}{K^2}\\

&\leqslant

|(i(F_{n+1})(x)|+2^{-n}\cdot\frac{\gamma}{4}.

\end{split}

\end{align*}Consequently,

In the same way, we observe that

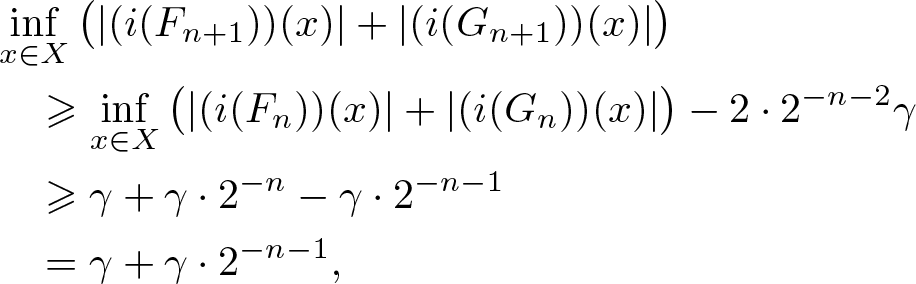

We conclude from (3.11) and (3.19)–(3.20) that

\begin{align*}

\begin{split}

& \inf_{x\in X}\big(|(i(F_{n+1}))(x)|+|(i(G_{n+1}))(x)|\big)\\

& \quad \geqslant

\inf_{x\in X}\big(|(i(F_{n}))(x)|+|(i(G_{n}))(x)|\big)

-2\cdot 2^{-n-2}\gamma

\\

& \quad \geqslant

\gamma+\gamma\cdot 2^{-n}-\gamma\cdot 2^{-n-1}\\

& \quad =\gamma+\gamma\cdot 2^{-n-1},

\end{split}

\end{align*}

\begin{align*}

\begin{split}

& \inf_{x\in X}\big(|(i(F_{n+1}))(x)|+|(i(G_{n+1}))(x)|\big)\\

& \quad \geqslant

\inf_{x\in X}\big(|(i(F_{n}))(x)|+|(i(G_{n}))(x)|\big)

-2\cdot 2^{-n-2}\gamma

\\

& \quad \geqslant

\gamma+\gamma\cdot 2^{-n}-\gamma\cdot 2^{-n-1}\\

& \quad =\gamma+\gamma\cdot 2^{-n-1},

\end{split}

\end{align*}so (iii) is fulfilled for n + 1.

Finally, for (iv), by (3.9)–(3.10), (3.12), and (3.17), for ![]() $\varepsilon \in(0,1),$

$\varepsilon \in(0,1),$ ![]() $\gamma \in(0,1],$

$\gamma \in(0,1],$ ![]() $ K \geqslant 2,$ and

$ K \geqslant 2,$ and ![]() $C\geqslant 1$, we then have

$C\geqslant 1$, we then have

\begin{align*}

\|H_{n+1}\|_{A}

&\leqslant

\|H_n\|_{A}^2

\|\overline{F_n}\|_{A}

\|\overline{G_n}\|_{A}

\left\|\frac{1}{|F_n|^2+|G_n|^2}\right\|_{A}^2\nonumber\\

&=

\|H_n\|_{A}^2

\|F_n\|_{A}

\|G_n\|_{A}

\left\|\frac{1}{|F_n|^2+|G_n|^2}\right\|_{A}^2

\\

&\leqslant

\left(\varepsilon\cdot 2^{-n}\cdot\frac{\gamma}{CK^3T^2}\right)^2

\cdot K^2 \cdot \widehat{T}^2\nonumber\\

&\leqslant

\varepsilon \cdot 2^{-n}\cdot\frac{\gamma}{CK^3T^2} \cdot\frac{\gamma}{CK^3T^2} \cdot K^2 \cdot \widehat{T}^2\nonumber\\

&\leqslant

\varepsilon \cdot 2^{-n}\cdot\frac{\gamma}{CK^3T^2} \cdot \frac{1}{K}\nonumber\\

& \leqslant

\varepsilon\cdot 2^{-n-1}\cdot\frac{\gamma}{C K^3 T^2},

\end{align*}

\begin{align*}

\|H_{n+1}\|_{A}

&\leqslant

\|H_n\|_{A}^2

\|\overline{F_n}\|_{A}

\|\overline{G_n}\|_{A}

\left\|\frac{1}{|F_n|^2+|G_n|^2}\right\|_{A}^2\nonumber\\

&=

\|H_n\|_{A}^2

\|F_n\|_{A}

\|G_n\|_{A}

\left\|\frac{1}{|F_n|^2+|G_n|^2}\right\|_{A}^2

\\

&\leqslant

\left(\varepsilon\cdot 2^{-n}\cdot\frac{\gamma}{CK^3T^2}\right)^2

\cdot K^2 \cdot \widehat{T}^2\nonumber\\

&\leqslant

\varepsilon \cdot 2^{-n}\cdot\frac{\gamma}{CK^3T^2} \cdot\frac{\gamma}{CK^3T^2} \cdot K^2 \cdot \widehat{T}^2\nonumber\\

&\leqslant

\varepsilon \cdot 2^{-n}\cdot\frac{\gamma}{CK^3T^2} \cdot \frac{1}{K}\nonumber\\

& \leqslant

\varepsilon\cdot 2^{-n-1}\cdot\frac{\gamma}{C K^3 T^2},

\end{align*}which verifies (iv) for n + 1.

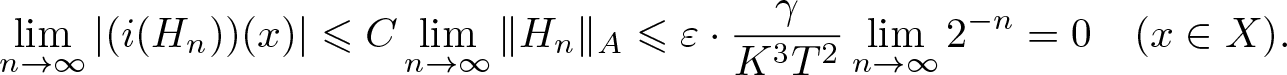

It follows from (3.1) and (iv) that

\begin{align}

\lim_{n\to\infty}|(i(H_n))(x)| \leqslant C\lim_{n\to\infty}\|H_n\|_A

\leqslant

\varepsilon\cdot\frac{\gamma}{K^3T^2}\lim_{n\to\infty}2^{-n}=0 \quad (x\in X).

\end{align}

\begin{align}

\lim_{n\to\infty}|(i(H_n))(x)| \leqslant C\lim_{n\to\infty}\|H_n\|_A

\leqslant

\varepsilon\cdot\frac{\gamma}{K^3T^2}\lim_{n\to\infty}2^{-n}=0 \quad (x\in X).

\end{align} Suppose that ![]() $m,n \in \mathbb{N}$,

$m,n \in \mathbb{N}$, ![]() $m \gt n.$ For

$m \gt n.$ For ![]() $\varepsilon \in(0,1),$

$\varepsilon \in(0,1),$ ![]() $\gamma \in(0,1],$

$\gamma \in(0,1],$ ![]() $ K \geqslant 2,$

$ K \geqslant 2,$ ![]() $C\geqslant 1$, and

$C\geqslant 1$, and ![]() $T\geqslant 1$, by (3.7), (3.10), (3.12), (3.17), we observe that

$T\geqslant 1$, by (3.7), (3.10), (3.12), (3.17), we observe that

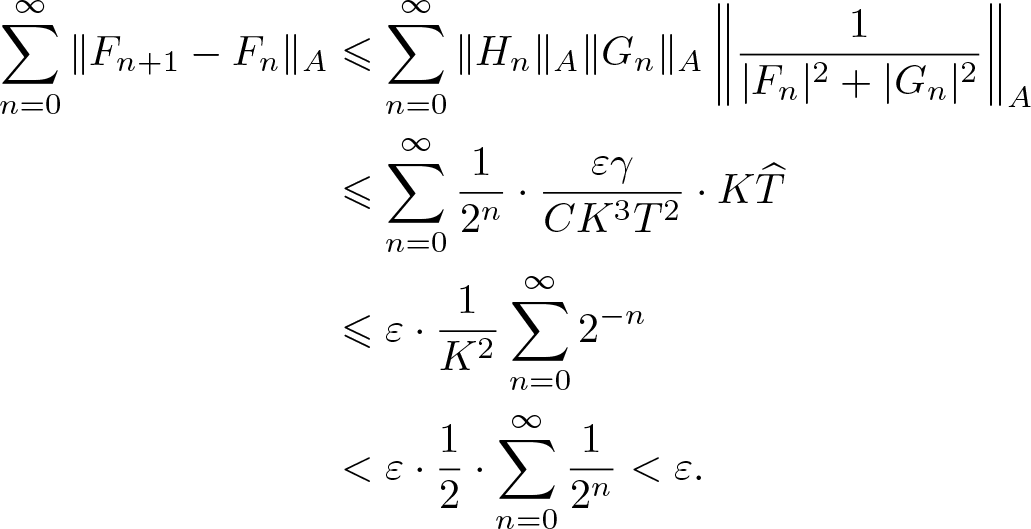

\begin{align}

\begin{split}

\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \|F_{n+1}-F_n\|_{A}&\leqslant

\sum_{n=0}^\infty

\|H_n\|_{A}

\|G_n\|_{A}

\left\|\frac{1}{|F_n|^2+|G_n|^2}\right\|_{A}\\

&\leqslant

\sum_{n=0}^\infty \frac{1}{2^n}\cdot\frac{\varepsilon\gamma}{CK^3T^2}

\cdot K\widehat{T} \\

& \leqslant

\varepsilon \cdot \frac{1}{K^2}\sum_{n=0}^\infty 2^{-n}\\

& \lt \varepsilon \cdot \frac{1}{2}\cdot \sum_{n=0}^\infty \frac{1}{2^n} \lt \varepsilon.

\end{split}

\end{align}

\begin{align}

\begin{split}

\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \|F_{n+1}-F_n\|_{A}&\leqslant

\sum_{n=0}^\infty

\|H_n\|_{A}

\|G_n\|_{A}

\left\|\frac{1}{|F_n|^2+|G_n|^2}\right\|_{A}\\

&\leqslant

\sum_{n=0}^\infty \frac{1}{2^n}\cdot\frac{\varepsilon\gamma}{CK^3T^2}

\cdot K\widehat{T} \\

& \leqslant

\varepsilon \cdot \frac{1}{K^2}\sum_{n=0}^\infty 2^{-n}\\

& \lt \varepsilon \cdot \frac{1}{2}\cdot \sum_{n=0}^\infty \frac{1}{2^n} \lt \varepsilon.

\end{split}

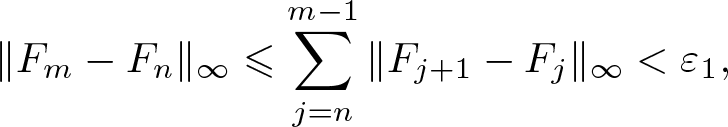

\end{align} Case 1. From (3.22) for any ![]() $\varepsilon_{1} \gt 0$, there exist N such that for

$\varepsilon_{1} \gt 0$, there exist N such that for ![]() $m,n \in \mathbb{N}, m \gt n \gt N$ holds

$m,n \in \mathbb{N}, m \gt n \gt N$ holds

\begin{align}

\begin{split}

\|F_m - F_n\|_{\infty}

&\leqslant

\sum_{j=n}^{m-1} \|F_{j+1}-F_j\|_{\infty} \lt \varepsilon_1,

\end{split}

\end{align}

\begin{align}

\begin{split}

\|F_m - F_n\|_{\infty}

&\leqslant

\sum_{j=n}^{m-1} \|F_{j+1}-F_j\|_{\infty} \lt \varepsilon_1,

\end{split}

\end{align} which means that the sequence ![]() $(F_n)_{n=1}^\infty$ is uniformly Cauchy, so it converges uniformly to some continuous function f. Similarly, there exists a continuous function g that is the limit of the uniformly convergent sequence

$(F_n)_{n=1}^\infty$ is uniformly Cauchy, so it converges uniformly to some continuous function f. Similarly, there exists a continuous function g that is the limit of the uniformly convergent sequence ![]() $(G_n)_{n=1}^{\infty}$.

$(G_n)_{n=1}^{\infty}$.

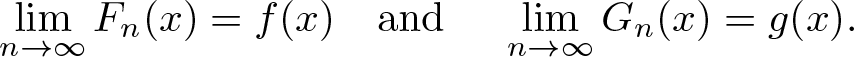

In particular, we obtain

\begin{align}

\lim_{n\rightarrow \infty} F_n(x) = f(x) \quad \text{and } \quad \lim_{n\rightarrow \infty} G_n(x) = g(x).

\end{align}

\begin{align}

\lim_{n\rightarrow \infty} F_n(x) = f(x) \quad \text{and } \quad \lim_{n\rightarrow \infty} G_n(x) = g(x).

\end{align}Using (3.24), (i) and (3.21), we see that

\begin{align}

f(x)\cdot g(x) & = \lim\limits_{n\to\infty} \big( F_{n}(x) \cdot G_{n}(x) \big)\nonumber\\

& = \lim\limits_{n\to\infty}\big( F_{n}(x) \cdot G_{n}(x)+H_{n}(x)\big) \nonumber\\

& = F(x) \cdot G(x)+H(x).

\end{align}

\begin{align}

f(x)\cdot g(x) & = \lim\limits_{n\to\infty} \big( F_{n}(x) \cdot G_{n}(x) \big)\nonumber\\

& = \lim\limits_{n\to\infty}\big( F_{n}(x) \cdot G_{n}(x)+H_{n}(x)\big) \nonumber\\

& = F(x) \cdot G(x)+H(x).

\end{align}Moreover, from (3.22), we have

\begin{align}

\begin{split}

\|f-F\|_{\infty}

&\leqslant

\sum_{n=0}^\infty \|F_{n+1}-F_n\|_{\infty} \lt \varepsilon.

\end{split}

\end{align}

\begin{align}

\begin{split}

\|f-F\|_{\infty}

&\leqslant

\sum_{n=0}^\infty \|F_{n+1}-F_n\|_{\infty} \lt \varepsilon.

\end{split}

\end{align} We show that ![]() $\|g-G\|_{\infty} \lt \varepsilon$ in the same way.

$\|g-G\|_{\infty} \lt \varepsilon$ in the same way.

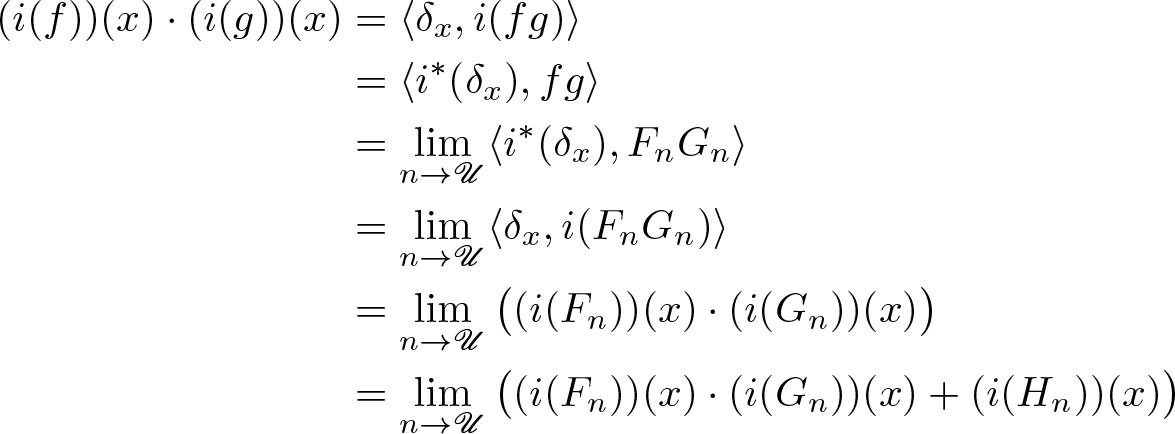

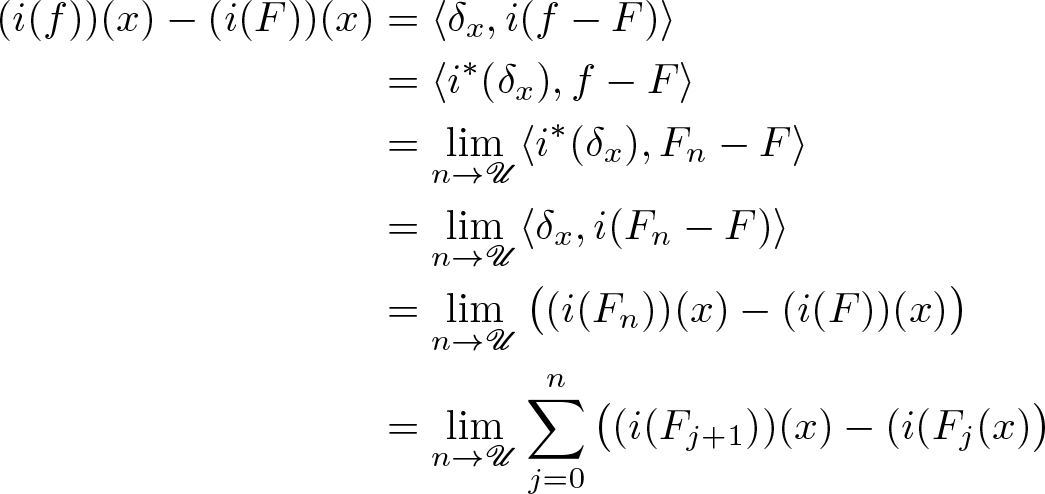

Case 2. A is a dual Banach algebra with ![]() $A = E^*$ that shares with X densely many points as witnessed by some dense set

$A = E^*$ that shares with X densely many points as witnessed by some dense set ![]() $Q\subset X$.

$Q\subset X$.

In view of (ii), the sequences ![]() $(F_n)_{n=0}^\infty$ and

$(F_n)_{n=0}^\infty$ and ![]() $(G_n)_{n=0}^\infty$ are uniformly bounded by constant K. Let

$(G_n)_{n=0}^\infty$ are uniformly bounded by constant K. Let ![]() $\mathscr U$ be a non-principal ultrafilter on

$\mathscr U$ be a non-principal ultrafilter on ![]() $\mathbb N$. By the Banach–Alaoglu theorem,

$\mathbb N$. By the Banach–Alaoglu theorem, ![]() $(F_n)_{n=0}^\infty$ and

$(F_n)_{n=0}^\infty$ and ![]() $(G_n)_{n=0}^\infty$ converge to some elements

$(G_n)_{n=0}^\infty$ converge to some elements ![]() $f,g\in A$,

$f,g\in A$, ![]() $\|f\|, \|g\|\leqslant K$ with respect to

$\|f\|, \|g\|\leqslant K$ with respect to ![]() $\sigma(A,E)$ along

$\sigma(A,E)$ along ![]() $\mathscr{U}$. Using (i) and (3.21), we see that for any

$\mathscr{U}$. Using (i) and (3.21), we see that for any ![]() $x\in Q$

$x\in Q$

\begin{align}

\begin{split}

(i(f))(x)\cdot (i(g))(x) & = \langle \delta_x, i(fg)\rangle\\

& = \langle i^*(\delta_x), fg\rangle\\

& = \lim_{n\to\mathscr{U}}\langle i^*(\delta_x), F_{n}G_n\rangle\\

& = \lim_{n\to\mathscr{U}}\langle \delta_x, i(F_{n}G_n)\rangle\\

& = \lim_{n\to\mathscr{U}} \big( (i(F_{n}))(x)\cdot (i(G_{n}))(x) \big)\\

& = \lim_{n\to\mathscr{U}}\big((i(F_{n}))(x) \cdot (i(G_{n}))(x)+(i(H_{n}))(x)\big)

\end{split}

\end{align}

\begin{align}

\begin{split}

(i(f))(x)\cdot (i(g))(x) & = \langle \delta_x, i(fg)\rangle\\

& = \langle i^*(\delta_x), fg\rangle\\

& = \lim_{n\to\mathscr{U}}\langle i^*(\delta_x), F_{n}G_n\rangle\\

& = \lim_{n\to\mathscr{U}}\langle \delta_x, i(F_{n}G_n)\rangle\\

& = \lim_{n\to\mathscr{U}} \big( (i(F_{n}))(x)\cdot (i(G_{n}))(x) \big)\\

& = \lim_{n\to\mathscr{U}}\big((i(F_{n}))(x) \cdot (i(G_{n}))(x)+(i(H_{n}))(x)\big)

\end{split}

\end{align}nonetheless, it follows from (i) that

hence for any ![]() $x \in Q$ we have

$x \in Q$ we have

Since Q is a dense subset of ![]() $X,$ by continuity of i and elements belonging to

$X,$ by continuity of i and elements belonging to ![]() $C(X),$ there are equal everywhere. This means that

$C(X),$ there are equal everywhere. This means that

because i is injective. Similarly, for ![]() $x\in Q$

$x\in Q$

\begin{align}

\begin{split}

(i(f))(x)-(i(F))(x) &=

\langle \delta_x, i(f-F)\rangle\\

&=

\langle i^*(\delta_x), f-F\rangle\\

&=

\lim_{n\to\mathscr{U}} \langle i^*(\delta_x), F_{n}-F\rangle\\

&=

\lim_{n\to\mathscr{U}} \langle \delta_x, i(F_{n}-F)\rangle\\

&=

\lim_{n\to\mathscr{U}}\big( (i(F_{n}))(x)-(i(F))(x)\big)\\

&=

\lim_{n\to\mathscr{U}}\sum_{j=0}^{n}\big( (i(F_{j+1}))(x)-(i(F_j(x)\big)\\

\end{split}

\end{align}

\begin{align}

\begin{split}

(i(f))(x)-(i(F))(x) &=

\langle \delta_x, i(f-F)\rangle\\

&=

\langle i^*(\delta_x), f-F\rangle\\

&=

\lim_{n\to\mathscr{U}} \langle i^*(\delta_x), F_{n}-F\rangle\\

&=

\lim_{n\to\mathscr{U}} \langle \delta_x, i(F_{n}-F)\rangle\\

&=

\lim_{n\to\mathscr{U}}\big( (i(F_{n}))(x)-(i(F))(x)\big)\\

&=

\lim_{n\to\mathscr{U}}\sum_{j=0}^{n}\big( (i(F_{j+1}))(x)-(i(F_j(x)\big)\\

\end{split}

\end{align}but from (3.22) we know that

\begin{align*}

\sum_{n=0}^\infty \big\| i(F_{n+1})-i(F_n)\big\|_{\infty} \leqslant C \cdot \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \|F_{n+1}-F_n\|_{A},

\end{align*}

\begin{align*}

\sum_{n=0}^\infty \big\| i(F_{n+1})-i(F_n)\big\|_{\infty} \leqslant C \cdot \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \|F_{n+1}-F_n\|_{A},

\end{align*} so for any ![]() $x\in Q$

$x\in Q$

\begin{align*}

(i(f))(x)-(i(F))(x) = \sum_{n=0}^\infty \big( (i(F_{n+1}))(x)-(i(F_n))(x)\big),

\end{align*}

\begin{align*}

(i(f))(x)-(i(F))(x) = \sum_{n=0}^\infty \big( (i(F_{n+1}))(x)-(i(F_n))(x)\big),

\end{align*} hence, again by density of Q in ![]() $X,$ continuity of i and elements belonging to

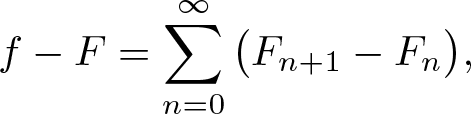

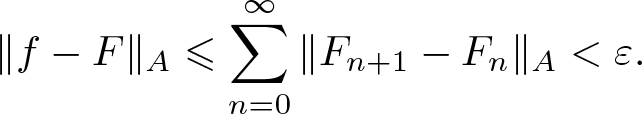

$X,$ continuity of i and elements belonging to ![]() $C(X),$ we have this equality everywhere. Moreover, since i is injective, we obtain

$C(X),$ we have this equality everywhere. Moreover, since i is injective, we obtain

\begin{align*}

f-F = \sum_{n=0}^\infty \big( F_{n+1}-F_n\big),

\end{align*}

\begin{align*}

f-F = \sum_{n=0}^\infty \big( F_{n+1}-F_n\big),

\end{align*}so from (3.22) we have

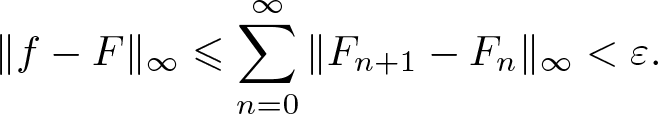

\begin{align}

\begin{split}

\|f-F\|_{A}

&\leqslant

\sum_{n=0}^\infty \|F_{n+1}-F_n\|_{A} \lt \varepsilon.

\end{split}

\end{align}

\begin{align}

\begin{split}

\|f-F\|_{A}

&\leqslant

\sum_{n=0}^\infty \|F_{n+1}-F_n\|_{A} \lt \varepsilon.

\end{split}

\end{align} We show that ![]() $\|g-G\|_{A} \lt \varepsilon$ in the same way.

$\|g-G\|_{A} \lt \varepsilon$ in the same way.

In each of the above cases, we have obtained the appropriate functions f and g, which, to simplify the notation, have been marked with the same symbols. So, for every ![]() $H \in A$ satisfying (3.5), there exist f and g in A such that

$H \in A$ satisfying (3.5), there exist f and g in A such that

(see respectively (3.26) or (3.31)) and ![]() $FG + H = fg$ (see respectively (3.25) or (3.29)). This means that

$FG + H = fg$ (see respectively (3.25) or (3.29)). This means that

with  $\delta:=\varepsilon\cdot \frac{\gamma}{C K^3 T^2}$. Hence, the multiplication in A is locally open at the pair

$\delta:=\varepsilon\cdot \frac{\gamma}{C K^3 T^2}$. Hence, the multiplication in A is locally open at the pair ![]() $(F,G)\in A^2$.

$(F,G)\in A^2$.

Suppose now that i has dense range in C(X). By inverse-closedness of A, A has topological stable rank 1 if and only if C(X) has topological stable rank 1. Consequently, if C(X) fails to have dense invertibles (which happens exactly when ![]() $\dim X \gt 1$), then A does not have open multiplication.

$\dim X \gt 1$), then A does not have open multiplication.

Applying Theorem 1.1, we obtain the following conclusion.

Corollary 3.1. Suppose that A is a unital Banach *-algebra such that there exists an injective *-homomorphism ![]() $i\colon A\to C(X)$ for some compact space X such that A is a differential subalgebra of C(X). Let us consider either case:

$i\colon A\to C(X)$ for some compact space X such that A is a differential subalgebra of C(X). Let us consider either case:

•

$A = C(X)$,

$A = C(X)$,•

$A = E^*$ is a dual Banach algebra that shares with X densely many points.

$A = E^*$ is a dual Banach algebra that shares with X densely many points.

Then multiplication in A is open at all pairs of jointly non-degenerate elements.

Corollary 3.2. Let A be a (complex) reflexive Banach space with a K-unconditional basis ![]() $(e_\gamma)_{\gamma\in \Gamma}$

$(e_\gamma)_{\gamma\in \Gamma}$ ![]() $(K\geqslant 1)$. Then A is naturally a Banach *- algebra when endowed with multiplication

$(K\geqslant 1)$. Then A is naturally a Banach *- algebra when endowed with multiplication

\begin{align*}

a \cdot b = \sum_{\gamma\in \Gamma} a_\gamma b_\gamma e_\gamma \quad (a = \sum_{\gamma\in \Gamma} a_\gamma e_\gamma, b = \sum_{\gamma\in \Gamma} b_\gamma e_\gamma\in A)

\end{align*}

\begin{align*}

a \cdot b = \sum_{\gamma\in \Gamma} a_\gamma b_\gamma e_\gamma \quad (a = \sum_{\gamma\in \Gamma} a_\gamma e_\gamma, b = \sum_{\gamma\in \Gamma} b_\gamma e_\gamma\in A)

\end{align*} and coordinate-wise complex conjugation. Let ![]() $A^\#$ denote the unitization of A. Then

$A^\#$ denote the unitization of A. Then ![]() $A^\#$ has open multiplication.

$A^\#$ has open multiplication.

Proof. It is clear any pair of elements of ![]() $A^\#$ is approximable by jointly non-degenerate products (see definition 2.3). Since the basis

$A^\#$ is approximable by jointly non-degenerate products (see definition 2.3). Since the basis ![]() $(e_\gamma)_{\gamma\in \Gamma}$ is K-unconditional, we have

$(e_\gamma)_{\gamma\in \Gamma}$ is K-unconditional, we have

\begin{align*}

\begin{split}

\|ab\|_A &=

\bigg\| \sum_{\gamma\in \Gamma} a_\gamma b_\gamma e_\gamma \bigg\|_A \\

&\leqslant K \bigg\|\sum_{\gamma\in \Gamma} a_\gamma \cdot \|b\|_{\ell_\infty(\Gamma)} \cdot e_\gamma \bigg\|_A \\

&=K\|a\|_A \|b\|_{\ell_\infty(\Gamma)}\\

&\leqslant K(\|a\|_A \|b\|_{\ell_\infty(\Gamma)}+\|a\|_{\ell_\infty(\Gamma)}\|b\|_A).

\end{split}

\end{align*}

\begin{align*}

\begin{split}

\|ab\|_A &=

\bigg\| \sum_{\gamma\in \Gamma} a_\gamma b_\gamma e_\gamma \bigg\|_A \\

&\leqslant K \bigg\|\sum_{\gamma\in \Gamma} a_\gamma \cdot \|b\|_{\ell_\infty(\Gamma)} \cdot e_\gamma \bigg\|_A \\

&=K\|a\|_A \|b\|_{\ell_\infty(\Gamma)}\\

&\leqslant K(\|a\|_A \|b\|_{\ell_\infty(\Gamma)}+\|a\|_{\ell_\infty(\Gamma)}\|b\|_A).

\end{split}

\end{align*} This means that ![]() $A^\#$ is a differential subalgebra of

$A^\#$ is a differential subalgebra of ![]() $c(\Gamma)$, the unitization of the algebra of functions that vanish at infinity on Γ. Since the formal inclusion from

$c(\Gamma)$, the unitization of the algebra of functions that vanish at infinity on Γ. Since the formal inclusion from ![]() $A^\#$ to

$A^\#$ to ![]() $c(\Gamma)$ has dense range, the conclusion follows.

$c(\Gamma)$ has dense range, the conclusion follows.

We now turn our attention to Theorem 1.4.

Proof of Theorem 1.4

By Lemma 2.6, there exists an ultrafilter ![]() $\mathscr{U}$ such that

$\mathscr{U}$ such that ![]() $\mathbb Z^{(\mathbb R)}$ embeds into

$\mathbb Z^{(\mathbb R)}$ embeds into ![]() $G^{\mathscr{U}}$. As

$G^{\mathscr{U}}$. As ![]() $\mathbb Z^{(\mathbb R)}$ is a free Abelian group, it admits a surjective homomorphism φ onto

$\mathbb Z^{(\mathbb R)}$ is a free Abelian group, it admits a surjective homomorphism φ onto ![]() $\mathbb{Q}^{(\mathbb N)}$. Since

$\mathbb{Q}^{(\mathbb N)}$. Since ![]() $\mathbb{Q}^{(\mathbb N)}$ is divisible, it is an injective object in the category of Abelian groups, so φ extends to a homomorphism

$\mathbb{Q}^{(\mathbb N)}$ is divisible, it is an injective object in the category of Abelian groups, so φ extends to a homomorphism ![]() $\overline{\varphi}\colon G^{\mathscr{U}}\to \mathbb{Q}^{(\mathbb N)}$. In particular, the infinite-dimensional space

$\overline{\varphi}\colon G^{\mathscr{U}}\to \mathbb{Q}^{(\mathbb N)}$. In particular, the infinite-dimensional space  $\widehat{\mathbb{Q}^{(\mathbb N)}}\cong \mathbb T^{\mathbb N}$ embeds topologically into

$\widehat{\mathbb{Q}^{(\mathbb N)}}\cong \mathbb T^{\mathbb N}$ embeds topologically into ![]() $\widehat{G^{\mathscr{U}}}$.

$\widehat{G^{\mathscr{U}}}$.

Consequently, ![]() $\dim \widehat{G^{\mathscr{U}}} = \infty \gt 1$. By [Reference Draga and Kania16, corollary 4.10], multiplication in

$\dim \widehat{G^{\mathscr{U}}} = \infty \gt 1$. By [Reference Draga and Kania16, corollary 4.10], multiplication in ![]() $\ell_1(G^{\mathscr{U}})$ is not open. However,

$\ell_1(G^{\mathscr{U}})$ is not open. However, ![]() $\ell_1(G^{\mathscr{U}})$ is a quotient of the Banach-algebra ultrapower

$\ell_1(G^{\mathscr{U}})$ is a quotient of the Banach-algebra ultrapower ![]() $(\ell_1(G))^{\mathscr{U}}$ ([Reference Draga and Kania16, §2.3.2]), so by [Reference Draga and Kania16, corollary 3.3], convolution in

$(\ell_1(G))^{\mathscr{U}}$ ([Reference Draga and Kania16, §2.3.2]), so by [Reference Draga and Kania16, corollary 3.3], convolution in ![]() $\ell_1(G)$ is not uniformly open.

$\ell_1(G)$ is not uniformly open.

4. Proof of Theorem 1.5

The present section is devoted to the proof of Theorem 1.5. We start by proving a special case of ![]() $X = [0,1]$; the argument is a slightly improved version of a proof due to Behrends. We are indebted for his permission to include it here.

$X = [0,1]$; the argument is a slightly improved version of a proof due to Behrends. We are indebted for his permission to include it here.

Theorem 4.1 The (complex) algebra ![]() $C[0,1]$ has uniformly open multiplication.

$C[0,1]$ has uniformly open multiplication.

In order to prove Theorem 4.1, we require further auxiliary results.

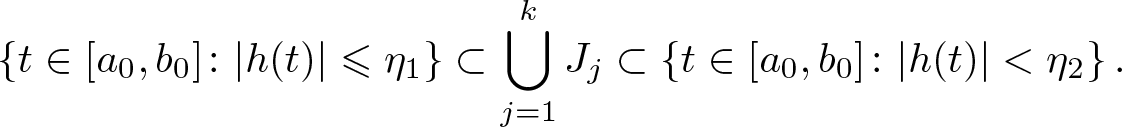

Anywhere below Δ will denote a set of all ![]() $(\alpha, \beta, \gamma) \in \mathbb{C}^{3}$ such that

$(\alpha, \beta, \gamma) \in \mathbb{C}^{3}$ such that ![]() $|\gamma|=1$ and the polynomial

$|\gamma|=1$ and the polynomial ![]() $\gamma z^{2}+\beta z+\alpha$ has two roots of different absolute value. In particular, in this situation, there is a uniquely determined root, so we can introduce the following definition

$\gamma z^{2}+\beta z+\alpha$ has two roots of different absolute value. In particular, in this situation, there is a uniquely determined root, so we can introduce the following definition

Definition 4.2. We denote by ![]() $Z\colon \Delta \rightarrow \mathbb{C}$ the map that assigns to

$Z\colon \Delta \rightarrow \mathbb{C}$ the map that assigns to ![]() $(\alpha, \beta, \gamma)$ the root of the quadratic polynomial

$(\alpha, \beta, \gamma)$ the root of the quadratic polynomial ![]() $\gamma z^{2}+\beta z+\alpha$ with the smaller absolute value.

$\gamma z^{2}+\beta z+\alpha$ with the smaller absolute value.