INTRODUCTION

Documents in the Linear B writing system almost exclusively take the form of clay tablets, which were used for record-keeping in the administrative centres of Late Bronze Age Greece (c. 1400–1200 BCE). The tablets themselves generally receive less attention than the texts written on them, which provide a wealth of information on Late Bronze Age Greek society as well as representing the earliest recorded form of the Greek language. However, the process of shaping clay to form tablets prior to writing on them is a crucial stage in the creation of these texts: focusing on this less-studied aspect of the Linear B documents sheds light not only on their materiality, but also on the operation of the whole administrative recording process.

In this study, I combine experimental tablet production with autopsy of the original tablets from Pylos in south-western mainland Greece. As the majority of the c. 1000 Linear B texts from this palace are securely associated with its final destruction, c. 1200–1180 BCE (early Late Helladic [LH] IIIC),Footnote 1 this site provides an opportunity to investigate the practices of a single, contemporaneous community of tablet-makers and -writers.

Previous experimental work

Many Mycenologists will have made replica Linear B tablets at some point, with students or as a public engagement activity,Footnote 2 if not as part of experimental research. Examples of the latter include creating tablets to test the use of the styli found at Tiryns (Godart Reference Godart1988, 248–50; Reference Godart and Marazzi1994; on styli, see also Steele Reference Steele2020); experiments carried out as part of Sjöquist and Åström's (Reference Sjöquist and Åström1991, 19–25) investigations into tablet production; demonstrations that dry tablets could be re-wetted in order to edit their texts (Pape Reference Pape2002; Pape et al. Reference Pape, Halstead, Bennet, Stangidis, Galanakis, Wilkinson and Bennet2014) and that they could survive being transported long distances (Hallager Reference Hallager, Nosch and Enegren2017); and an investigation of the means of smoothing tablet surfaces and edges (Greco and Flouda Reference Greco and Flouda2017, 149–51). The different methods used for creating tablets – and what reasons a tablet-maker might have to choose one over another – have, however, not previously been the subject of systematic experimental investigation. This study therefore seeks to improve our understanding of the processes involved in shaping clay to form tablets, the impact of the choice of particular methods of doing so, and hence the considerations in play for the tablet-makers during this procedure.

How were tablets made?

The first stage of creating a tablet is, of course, the collection and processing of the clay.Footnote 3 A wide range of different clays appear to have been used at Pylos, including both fine and coarse clays, as observed by autopsy (Palaima Reference Palaima, Sjöquist and Åström1985; Reference Palaima1988), macroscopic petrographic analysis (Nakassis, Pluta and Hruby Reference Nakassis, Pluta, Hruby and Cooper2021, 168; Hruby and Nakassis Reference Hruby, Nakassis, Bennet, Karnava and Meißnerforthcoming), and portable X-ray fluorescence (Wilemon Reference Wilemon2017; Wilemon, Galaty and Nakassis Reference Wilemon, Galaty and Nakassis2020). However, pending full publication of the latter two studies, it is not possible to discuss this aspect of tablet production in detail, and this study focuses on the next stage of the process, shaping the clay to form a tablet.Footnote 4

Linear B tablets are classified into two formats (Fig. 1), ‘palm-leaf’ (long and narrow; usually one or two lines of text recording a single piece of information) or ‘page-shaped’ (rectangular, orientated horizontally or vertically,Footnote 5 with more lines of text and usually containing multiple administrative entries), although this classification obscures the great degree of variation in size and shape within each format, as well as the extent to which they can overlap in size and function (cf. Driessen Reference Driessen2000, 42; Palaima Reference Palaima, Duhoux and Davies2011, 104 n. 134; Tomas Reference Tomas, Nosch and Landenius Enegren2017, 120–1; and ‘Tablet-makers and tablet-writers’, below). Other document types include labels – small pieces of clay attached to baskets or trays containing tablets (see, e.g., PT 3, xliii–xliv, lxxi) – and sealings, which are usually three-sided and formed around a knotted string, bearing a seal impression and sometimes short inscriptions with information about the goods they accompanied from other locations to the palace.Footnote 6 It is often said that palm-leaf tablets were used for preliminary documentation, before the information from a set of palm-leaves was transferred to a page-shaped tablet as the final document (e.g. Palaima Reference Palaima and Cline2010, 360; Del Freo Reference Del Freo, Freo and Perna2019, 172). However, direct evidence for this multi-stage processing of administrative information is limited;Footnote 7 in many cases, a basket of related palm-leaf tablets could have formed the final ‘document’, while a page-shaped tablet could have been the first and only stage of documentation.Footnote 8

Fig. 1. Illustration of tablet shapes: palm-leaf (Fr 1203, top left); vertical page-shaped (An 1, right); horizontal page-shaped (Es 647, bottom left). Photos: National Archaeological Museum, Athens/ Department of Collections for Prehistoric, Egyptian, Cypriot and Near Eastern Antiquities. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/ Organization of Cultural Resources Development (H.O.C.RE.D.). Scale bar: adapted from photographic reference scale by Jim Elder, Ottawa, Canada (smallpond.ca/jim/scale), CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0.

The most systematic previous discussions of methods of making tablets are provided by Palaima's (Reference Palaima1988) descriptions of the characteristics of tablets written by different scribes at Pylos, which in some cases include the techniques used to create them, and by Sjöquist and Åström's (Reference Sjöquist and Åström1985; Reference Sjöquist and Åström1991) studies of the palmprints on the Pylos and Knossos tablets, both of which will be further discussed below. General comments on the process of making tablets usually relate to palm-leaves, and describe sheets of clay being folded up to form long narrow tablets (e.g. Palaima Reference Palaima, Sjöquist and Åström1985, 103; Reference Palaima, Duhoux and Davies2011, 105–6; Del Freo Reference Del Freo, Freo and Perna2019, 172–3); however, palm-leaves could also be made by rolling out a cylinder of clay and flattening it with the palms (Sjöquist and Åström Reference Sjöquist and Åström1985, 44; Reference Sjöquist and Åström1991, 13–16, 18; Driessen Reference Driessen2000, 41; Fig. 2) or simply by moulding the clay into shape with the fingers.Footnote 9 Some tablets – usually, but not exclusively, palm-leaves – also had a piece of straw or string inserted longitudinally, identifiable by the channel left through the tablet (see Godart Reference Godart1988, 248–9; Driessen Reference Driessen2000, 40; Palaima Reference Palaima, Duhoux and Davies2011, 105). The process of making page-shaped tablets is more rarely discussed, although Palaima (Reference Palaima1988, 46, 59; Reference Palaima, Duhoux and Davies2011, 105) states that some were made by moulding fine clay over a coarser core (but see ‘Experimental methodology’ below), and Bennett (Reference Bennett, De Miro, Godart and Sacconi1996, 29) refers to the edges of page-shaped tablets being folded over ‘to make nicely rectangular shapes’. The edges of tablets were also neatened by pressing against a flat surface (e.g. Driessen Reference Driessen2000, 41) or by burnishing (Greco and Flouda Reference Greco and Flouda2017, 149–50). Tablets were frequently cut along one or more sides, either to remove unused clay or to create multiple separate records (Palaima Reference Palaima, Sjöquist and Åström1985, 103; Reference Palaima1988; Tomas Reference Tomas, Piquette and Whitehouse2013).

Fig. 2. The author rolling out a cylinder of clay to form a tablet in the Fitch Laboratory. Photo: Evangelia Kiriatzi.

Where were tablets made?

At the time of Pylos’ destruction, c. 80 per cent of the tablets were stored in the ‘Archives Complex’, two rooms next to the palace's main entrance.Footnote 10 The rest are mostly from other areas of the palace where items were processed and/or stored (Palaima Reference Palaima1988, 135–69), including a pottery storeroom (Room 20); three oil storerooms (Rooms 23, 32, and above Room 38: Shelmerdine Reference Shelmerdine1985, ch. 4); the North-Eastern Building, a clearinghouse for receiving and recording goods (Bendall Reference Bendall2003); and the South-Western Building, where ‘taxation’ records were written.Footnote 11 Evidence that at least some of the tablets found in the Archives Complex had been transferred from other locations around the palace is provided by the Sa series of chariot wheel records: these were mostly found in the Archives Complex, but one remained in the North-Eastern Building, where presumably the whole series had been written (Palaima Reference Palaima1988, 179; Bendall Reference Bendall2003, 220). The Sh series, recording armour, were stacked in a labelled basket near the Archives Complex's doorway at the time of the destruction, and may also have just been transferred from the North-Eastern Building (Palaima Reference Palaima, De Miro, Godart and Sacconi1996a; see also Kyriakidis Reference Kyriakidis1996–7, 214–24). Presumably tablets were made in or near all of the areas in which they were found,Footnote 12 as well as potentially other areas in, or just outside, the palace. An outside area might often have been a more convenient place – with more space, better light, and less of a need to clean up clay – to make and write documents, especially compared to the Archives Complex's two small rooms (cf. Palaima and Wright Reference Palaima and Wright1985, 259). It is also increasingly frequently being suggested (though has not been conclusively proven) that some palm-leaf tablets, like sealings, may have been written away from the palace – whether by writers based at another administrative centre or by palace-based writers who had travelled to other locations – and brought back for filing and/or compiling onto summary documents.Footnote 13

Who made the tablets?

Whether tablets were made by the same person who wrote on them was a major question in Sjöquist and Åström's (Reference Sjöquist and Åström1985; Reference Sjöquist and Åström1991) studies of the palmprints left by the tablets’ makers. At Pylos, their results were inconclusive due to the limited number of identifiable prints: only four makers were found to have certainly or probably left prints on more than one tablet, while a further six could be distinguished by a single print each (compare the c. 30–40 identified scribal hands at this site).Footnote 14 The complex relationship between these prints and the scribal hands will be discussed below in more detail, but it suggests that in some cases the tablet's maker and writer may have been the same person, while in others different individuals were responsible for each stage of the process; whether the makers in the latter cases were other scribes or assistants is not clear.Footnote 15 In this paper, I use ‘tablet-maker’ to refer to each tablet's creator, and ‘writer’ to refer to the person who inscribed the text, regardless of whether a particular tablet-maker was or was not also a writer (of that or any other text) or vice versa. Combining experimental production of tablets with autopsy of the originals and analysis of the correspondences between their manufacturing technique, format, contents, palmprints, and scribal attributions will produce a fuller understanding of the relationships between the making and writing stages of Linear B tablet production, whether these were the work of one person or two.

INVESTIGATING TABLET PRODUCTION

Experimental methodology

The experiments described here were carried out in the Fitch Laboratory at the British School at Athens using clay from the region of Elis, to the north of Messenia (the clay available in the Fitch's reference collection which was closest both geographically and geologically to the region around Pylos). Although as stated above it was not possible, nor was it intended, to replicate the original clays used, I used three clays to imitate some of the range of clay types found: a fine, silty clay (Fitch Laboratory reference KAVGS17/06), a coarse clay (KAVGS17/15), and a very coarse clay (KAVGS17/04). The process of experimentation was, of course, also a learning process for me, involving a fair amount of trial-and-error in order to find out, for instance, what consistency of clay made it easiest to produce tablets using a particular method – something that an experienced Mycenaean tablet-maker would no doubt have known instinctively through long practice. It is important to bear in mind, particularly in the following discussions of the degree to which different production methods may have required more or less care or effort, that the tablet-maker's training and experience are unreplicable aspects of their practices.

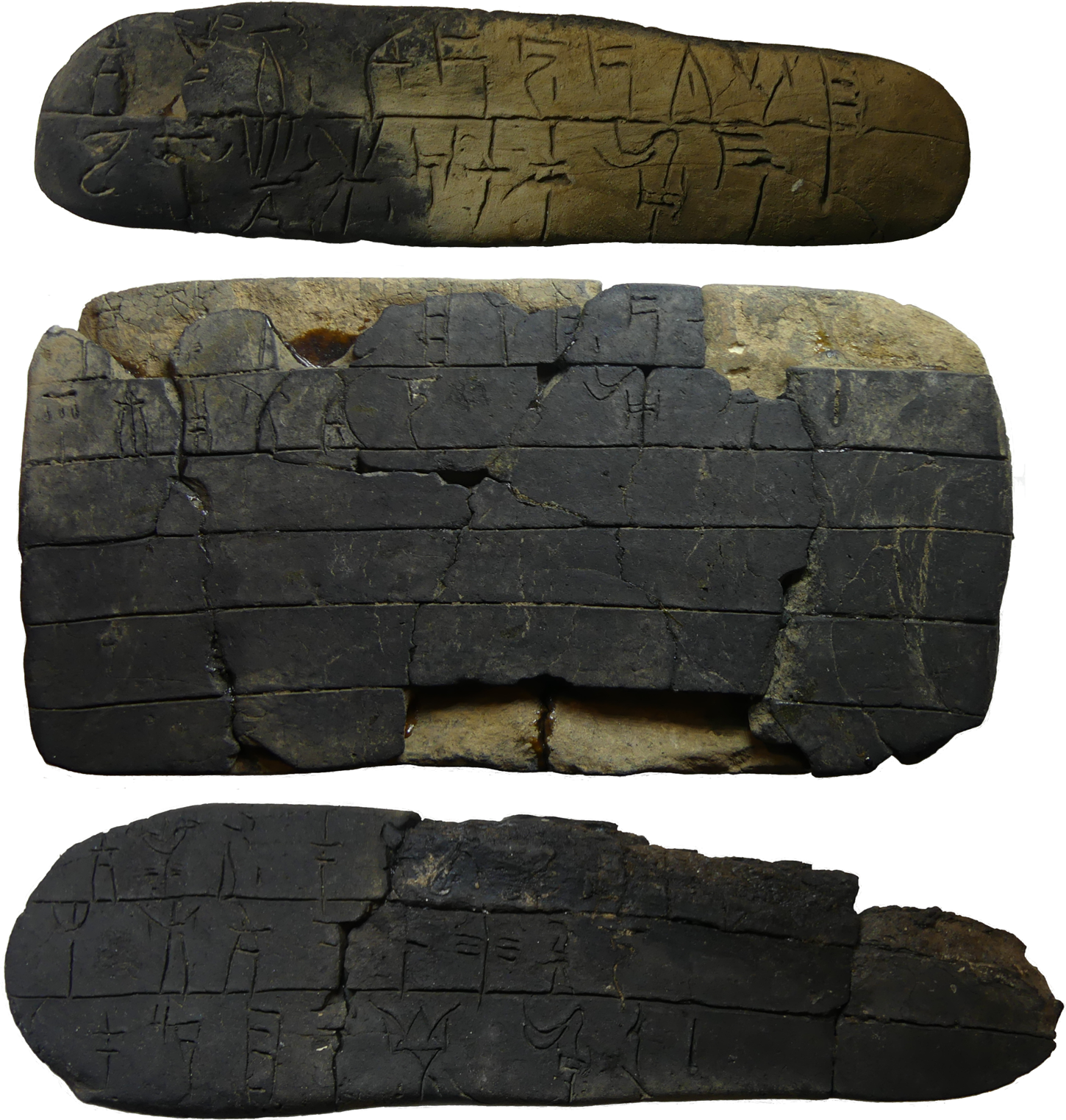

The initial experiments were carried out in parallel to the autopsy of the tablets in the National Archaeological Museum, so that each study could inform the other. One notable impact of the autopsy was that I observed no evidence for the claim that certain page-shaped tablets (Es 644 and Jn 605) were made by covering a coarse clay core with a layer of finer clay (Palaima Reference Palaima1988, 46, 59). On Jn 605 (Fig. 3), the appearance of a smooth layer of clay over a rougher layer on both the top and bottom edges is the result of the common practice of removing clay by cutting partway through the tablet (leaving a smooth surface, on which cut-marks are clearly visible) and then tearing it the rest of the way, leaving a rough surface; note that large inclusions can be seen in the smooth upper part as well as the rougher lower part. On Es 644, a similar effect is due to breakages along ruled lines, both at the bottom and various points in the middle of the tablet, producing the appearance of a finer upper layer. I therefore did not experiment with using a coarse core covered by a layer of finer clay.

Fig. 3. Jn 605 lat. inf. Photo: National Archaeological Museum, Athens/ Department of Collections for Prehistoric, Egyptian, Cypriot and Near Eastern Antiquities. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/ Organization of Cultural Resources Development (H.O.C.RE.D.).

Conversely, the most important impact of the experiments on the autopsy was – unfortunately – the observation that the traces left by creating rolled and folded tablets can be effectively indistinguishable: a folded tablet can appear identical to a rolled one if the seam on the verso has been entirely smoothed over and the ends have been pinched together or smoothed, and even the appearance of small seams on the ends does not necessarily indicate a folded tablet, since the ends of rolled tablets can be shaped in a similar way. Thus, although some tablets show clear signs of folding, many others are uncertain, and it is extremely difficult to be sure that a tablet has not been folded. In practice, therefore, it generally remains unclear how consistent any given series of tablets is in its method of manufacture.

Folded tablets

As stated above, although flattening out sheets of clay and then folding them up is often said to be the usual method of creating palm-leaf tablets, the simpler method of rolling out and flattening a cylinder of clay is also referred to; in his study of the Pylos tablets, Palaima (Reference Palaima1988) only mentions folding in reference to a few groups of tablets (H1's Aa series, and the Ma, Na, and Ta series). Page-shaped tablets are also sometimes folded, probably by folding a flattened sheet in half, since when seams are visible this is along one or more edges rather than in the middle of the verso as on palm-leaves. The folding method evidently has more requirements than the rolling-and-flattening method, needing a means of flattening out a sheet of clay (in my case, a rolling pin; I imagine that a similar implement would have been the easiest way for a Mycenaean tablet-maker to create a flat sheet, but no evidence for this exists), and a large enough surface on which to do this; it also requires more time and effort in neatening the resulting tablet by smoothing over the seam where the sheet was joined. (In practice, tablets made in this way are much more often identifiable from the visible edges of the folded sheet than from the seam, which is normally completely or almost completely smoothed over: Fig. 4.) In addition, experimentation showed that creating a folded tablet is much more dependent on the clay type and consistency – it is easier to do with fairly wet fine clay than with drier and/or coarser clay, though even then the edges tend to crack while being folded, and clay that is too wet tends to stick to the surface beneath it or to the rolling pin. However, both coarse and fine clay can be easily rolled and flattened even while comparatively dry. Creating folded tablets therefore would have required more planning and work at all stages of the process, from clay preparation to neatening the finished tablet, not to mention cleaning up the wetter clay – so why was this method sometimes chosen by the tablet-makers?

Fig. 4. Ma 123, lat. sin. and verso. The fold is clearly visible on the lat. sin. but there is only a trace of the seam at the left-hand end of the verso. Photos: National Archaeological Museum, Athens/ Department of Collections for Prehistoric, Egyptian, Cypriot and Near Eastern Antiquities. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/ Organization of Cultural Resources Development (H.O.C.RE.D.).

In preliminary experiments, I observed that after partly drying, folded tablets were less prone to bending than rolled ones. To test whether this effect lasted after fully drying, and therefore whether folded tablets were ultimately sturdier than rolled ones, I created a series of folded and rolled tablets of fine clay (the former using relatively wet clay, the latter using both wetter and drier clay).Footnote 16 These were left to dry outside until they were too dry to inscribe properly, tested by writing signs on each tablet every hour until the resulting strokes were very shallow (as seen on actual tablets when additions have been made some time after the initial writing; outdoors in Athens in July this took five to six hours: Fig. 5).Footnote 17 Weighing each tablet every hour showed no difference in drying rate – all tablets lost similar proportions of their mass every hour – and by the end of this period there was no observable physical difference between the folded and rolled tablets, none of which were at all flexible. A repetition of this experiment in which I observed the tablets’ flexibility – how much they naturally bent when held by the middle or (when dry enough that this did not happen) how much they could be deliberately bent without a risk of breaking – every hour showed that while initially the folded tablets were significantly less flexible than the rolled ones (Fig. 6), after one to two hours (depending on the clay's original consistency) all of the tablets were equally unable to be bent more than very slightly without cracking or breaking. Further experiments using the two coarser clays and with page-shaped tablets showed the same effect, although this was less pronounced for the very coarse clay (which produced less flexible tablets to begin with) and for page-shaped tablets (whose greater width relative to their length likewise made them less flexible even when wet).

Fig. 5. The author writing on drying tablets to test their consistency. Photo: Emily Sherriff.

Fig. 6. Experimental tablets made of fine clay (left) and coarse clay (right) showing effects of holding by the middle while wet. Top: rolled; bottom: folded. Photos: author.

Thus, the advantage of folding is a short-term one, increasing tablets’ stability only during a relatively short period after their creation. This method therefore seems intended to produce tablets which can more easily be handled while still relatively wet, reducing the risk of them bending or breaking at this stage. Almost all of the series which were inscribed while the clay was still fairly wet contain at least some tablets with clear traces of being made by folding (cf. above on the difficulty of establishing how consistently this method was used),Footnote 18 so that in these cases the makers’ intention could have been to facilitate the tablets’ inscription, whether by themselves or other writers. The same is, however, true of many series inscribed – as appears to have been more usual – after the clay had partially dried, implying that the tablet-makers’ concern may have been for the tablets to retain their shape until this point (for instance, if being moved to another position for drying). In this method of tablet-making, therefore, we may see interactions between multiple different stages of document creation: tablet-makers on some occasions chose a more complicated method, involving more steps and more care, in order to enable themselves and/or others to more easily handle the resulting tablet – whether during the rest of the manufacturing process or while inscribing the text.

Straws/string

Evidence of the inclusion of a piece of straw or string,Footnote 19 usually running horizontally through the centre of the tablet and identified by the holes left at its exit pointsFootnote 20 and/or the channel left through the tablet (Fig. 7), is found in five main series. These are listed below along with the proportion of each series which, based on autopsy, originally contained a straw/string:Footnote 21

-

Sh series (H5), palm-leaf records of suits of armour, found in the Archives Complex: 100 per cent (12/12).

-

Eb series (H41), palm-leaf first-stage landholding records, found in the Archives Complex: 97 per cent (61/63).Footnote 22

-

Sa series (H26), palm-leaf records of chariot wheels, found in the Archives Complex and North-Eastern Building: 94 per cent (33/35).Footnote 23

-

Eo series (H41), palm-leaf and page-shaped first-stage landholding records, found in the Archives Complex: 77–85 per cent (10–11/13).Footnote 24

-

Ad series (H23), palm-leaf personnel records of groups of men and boys (described by their relationship to the women workers recorded in the Aa series by H1 and H4)Footnote 25 at various locations in Pylos’ territory, found in the Archives Complex: 14–16 per cent (5–6/37).Footnote 26

Fig. 7. Eb 149 lat. dex., with straw/string hole (left); Sh 740 recto, with partially exposed straw/string channel (right). Photos: National Archaeological Museum, Athens/ Department of Collections for Prehistoric, Egyptian, Cypriot and Near Eastern Antiquities. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/ Organization of Cultural Resources Development (H.O.C.RE.D.).

In addition, straw/string holes appear in a small number of other tablets, including two of H21's Cc series (Cc 1283 and 1285, sheep records from the North-Eastern Building; it is not clear what administrative relationship, if any, these have to the rest of the Cc series, which lack this feature);Footnote 27 two Va series tablets attributed (tentatively) to H42 (Va 404 and 482, ivory-working records from the Archives Complex; there is no clear relationship to the other Va series records tentatively attributed to this hand);Footnote 28 and a small number of isolated, unattributed tablets.Footnote 29

The inclusion of these straws/strings has been suggested to have a variety of purposes: giving the tablet greater stability (Godart Reference Godart1988, 248–50; Reference Godart and Marazzi1994;Footnote 30 Palaima Reference Palaima1988, 27; Reference Palaima, Duhoux and Davies2011, 105–6;Footnote 31 Del Freo Reference Del Freo, Freo and Perna2019, 172–3); allowing the tablet to be lifted while still wet without distorting its shape or smudging the inscription (Palaima Reference Palaima, Ferioli, Fiandra and Fissore1996b, 104–5; Reference Palaima, Duhoux and Davies2011, 105); preventing the loss of any pieces broken off in handling or transportation (Bennett Reference Bennett, De Miro, Godart and Sacconi1996, 28–9; Palaima Reference Palaima, De Miro, Godart and Sacconi1996a, 382 n. 10; J.-P. Olivier in Palaima Reference Palaima, Ferioli, Fiandra and Fissore1996b, 105); or attaching sealings to tablets for authentication (E.L. Bennett in Palaima Reference Palaima, Ferioli, Fiandra, Fissore and Frangipane1994, 334–5; Palaima Reference Palaima, Ferioli, Fiandra and Fissore1996b; Flouda Reference Flouda2010, 65–6; Younger Reference Younger and Cline2010, 334; Panagiotopoulos Reference Panagiotopoulos2014, 190–1, 252–4). The last of these hypotheses is not, in my opinion, a plausible one: sealing as an authentication practice seems to have been required only at the administrative stage represented by the sealings – extremely short documents likely to have been written in multiple locations and sent to or from the palace along with the goods they registered – whereas the act of writing a palm-leaf or page-shaped tablet, whether this took place in or away from the palace (as discussed above), seems to have constituted all the authentication required. Otherwise, we would expect far more examples of tablets which could potentially have had sealings attached to them – or, indeed, the impression of seals directly onto the tablets themselves, as was frequently done on Ancient Near Eastern cuneiform documents.Footnote 32 Palaima (Reference Palaima, Ferioli, Fiandra and Fissore1996b) argued that the particular tablet series which show this feature at Pylos could have required special authentication, but also (since relatively few sealings have been found within the Archives Complex, where these series of tablets were all stored and where other records important enough to require authentication of this type would be most likely to have been kept)Footnote 33 that the individuals concerned in the records would have retained these sealings as ‘receipts’. However, if the sealings were not to be retained with the tablets, there would be no need for them to be attached in this way, and Palaima's (Reference Palaima, Duhoux and Davies2011, 105–6) own more recent summary of tablet manufacturing processes favours different suggestions (listed above).Footnote 34 The experiments therefore focused on the hypotheses that straws/strings provided extra stability, a means of moving the wet tablet, and/or a protection against the loss of broken fragments.

The experiments described above already demonstrated that the effect of folding was to give the tablet greater stability in the initial stages of drying. Subsequently, I tested the effect on this of incorporating a straw/string,Footnote 35 by creating rolled and folded tablets of fine and coarse clays with and without straws. Although incorporating the straw made a slight difference, folding made a much larger one – the unfolded tablets with straws were still very prone to bending (the thickness of both the straw and of the tablet also had some effect on this), while the folded tablets with straws, although the most stable option, were only slightly more so than the folded ones without straws (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8. Experimental tablets showing effects of holding by the middle while wet. From top to bottom: rolled, without straw; rolled, with straw; folded, without straw; folded, with straw. Photo: author.

Tablets made with a straw/string frequently have visible channels near one or both ends of the recto or verso,Footnote 36 sometimes even cutting through the beginning or end of the text,Footnote 37 while in the Sa and Sh series, whose clay was especially wet while inscribing, the edges of the straw/string holes are also sometimes distorted (e.g. Sa 487, 682, 794; Sh 739). Both of these features initially implied to me during autopsy that the straw/string had been partly pulled up out of the clay, as also happened in experiments if using the straw/string to lift a tablet that was wet enough to stick to the surface underneath, or if the straw/string was very near the surface of the tablet. However, experiments showed that trying to lift a sticking tablet in this way tended to result in a much longer portion of the straw/string being pulled out of the clay, significantly damaging the tablet; in addition, many tablets were clearly handled while the clay was wet, as shown by the presence of finger-marks on the top and bottom edges (e.g. Sa 753, 758, 766, 769, 790, 791, 834; Sh 743, 744). I therefore think it more likely that these channels were the result either of the tablet being formed in such a way that the straw/string exited the clay slightly before the end of the tablet, or (where the channel cuts through the text) of later accidents – the straw/string catching on something during handling or transportation, or the loss of the thin layer of clay above a straw/string running close to the tablet's surface after drying (as happened in one experimental case – see below).Footnote 38

Experiments in using straws/strings to lift tablets for a few seconds, in order to simulate a use such as transferring the wet tablet to another location to dry, produced mixed results. The end of the first trial example cracked and broke off completely after drying; further experiments demonstrated that it was possible to avoid this result, but that this was very variable and related to a variety of factors. In a second experiment, a tablet whose clay had been rolled around a straw cracked while one that had been folded did not; in a third, none of the range of tablets of various thicknesses (1–2.1 cm) made of relatively dry clay cracked or broke, but a single tablet made with much wetter clay (of medium thickness: 1.5 cm) developed a large crack near the middle. Finally, a series of tablets were made to test more systematically the impact of the consistency of the clay and of folding the clay around the straw/string or rolling it, as well as whether lifting by only one end of the straw/string, rather than both, could prevent breakage. In this case nearly all of the tablets (rolled or folded; containing straw or string; made of drier or wetter clay or fine or coarse clay; carried by one end or both ends of the straw/string) remained undamaged, while a single tablet (made of drier clay, folded, and carried by one end) cracked slightly. Thus, although damage to tablets from this use was not inevitable, it is certainly unreliable and carries the risk of greater damage than would be caused simply by handling the clay itself – as the finger-marks mentioned above imply frequently happened. There is also no correlation between the consistency of the clay while inscribing and the presence of straws/strings: the Sa and Sh series were inscribed while the clay was still relatively wet, but so were the Ad series (with only a minority containing straws/strings) and the Aa, Es, and Qa series (with no straws/strings); conversely, the Eb and Eo series were not particularly wet when inscribed (cf. Palaima Reference Palaima1988, 70, 87, 91, 98–9, 121).

Finally, to test the ability of straws/strings to prevent the loss of broken fragments, eight tablets were created (of fine and coarse clay, rolled and folded around straws and strings), left to dry, and then transported from Athens to the UK and back in hand luggage.Footnote 39 Two were deliberately broken in the lab, a third broke before leaving when accidentally dropped, and two further tablets broke in transit. On returning to Athens, three of the broken tablets – including one which had broken into five pieces – were still held together by their straws/strings (Fig. 9:1–3), one had lost a fragment from the end where the string had been pulled out of the tablet before drying (Fig. 9:5), and only one had lost a piece that had contained the string (Fig. 9:4): as the string had been very close to the tablet's edge, damage to the surface resulted in the string coming loose (or, alternatively, the surface was broken by tension on the string).Footnote 40 While not a fool-proof method, then, using a straw/string would have significantly lessened the risk of losing fragments from any tablets which broke during transportation – whether they were being transported from another part of the palace to the Archives Complex, or to Pylos from another location within the Pylian territory.

Fig. 9. Broken tablets containing straws/strings on their return to Athens. Photo: author.

These experiments suggest that the most likely purpose(s) of the straws/string were to increase the tablets’ stability (in combination with folding) and/or to keep fragments together in case of breakage during short- and/or long-distance transportation. Unfortunately, the series with straw/string holes show no particular patterns in terms of findspot or subject-matter to suggest that they are more likely than others to have been transported either to or within the palace. As said above, the Sa and Sh series may well both have been transferred to the Archives Complex from the North-Eastern Building; however, of the tablets actually found in the North-Eastern Building only two of H21's four Cc series tablets have straw/string holes.Footnote 41 Of the series containing (some) straw/string holes, only the Ad, Eb and Eo series explicitly record activities taking place in locations outside of the palace.Footnote 42 In the Ad series, which records work-groups located in both the ‘Hither Province’ (southern and western Messenia, including Pylos itself) and the ‘Further Province’ (the area to the east of the Aigaleon mountain range),Footnote 43 there is no correlation between the presence or absence of straw/string holes and the location referred to.Footnote 44 Moreover, neither H1's Aa series tablets, which list the related work-groups of women and children in the Hither Province records, nor H4's, which list the same for the Further Province, contained straws/strings (H21's Ab series, which also lacks this feature, contains records of rations only for the Hither Province work-groups). The Eb and Eo series refer to landholdings at a place called pa-ki-ja-ne (perhaps /Sphagianes/), the site of a religious sanctuary near the palace, but whether they were written on a ‘site visit’Footnote 45 or based on information conveyed orally or on other written materials from that location remains unknown. H43's Ea series of palm-leaf tablets, which record similar (though less detailed) landholding information about another, unknown, location (Lejeune Reference Lejeune and Lejeune1997), are made without straws/strings; it is possible that this reflects a difference in writing location, but there is no other positive evidence for this. The hypothesis that an administrative reason (such as the need to transport these preliminary documents from the location of their writing) underlies the use of straws/strings, rather than a purely physical reason relating to tablet manufacture, is supported by the lack of a relationship between the distribution of straws/strings and tablet shape/size in the series in which these are used inconsistently (the Ad and Eo series).Footnote 46 It is similarly supported by the fact that, in the only series to contain straws/strings in page-shaped tablets (the Eo series), these are functionally identical to the palm-leaves as first-stage administrative documents.Footnote 47 However, the lack of a definite correlation between tablets’ likely movements and the presence or absence of straws/strings, along with the probability that more than just these fairly restricted groups of tablets were moved around, make it most likely that incorporating straws/strings was an option for tablet-makers to consider, not a requirement when making tablets that would be moved around within, and perhaps to, the palace.

Tablet shape and finishing

Palm-leaf tablets characteristically have a tapering shape, with one or both ends narrower than the middle in width and/or height, the latter meaning that the ends of the verso frequently curve up (Fig. 10). My experiments showed that this shape naturally occurs when a cylinder of clay is flattened with both hands positioned near the ends, or when a sheet of clay is flattened using a rolling pin before folding up, since in both cases more pressure is put on the edges than the middle. Of course, the exact shape could be adjusted both in the course of rolling/flattening (by shifting hand position or altering the amount of pressure) and once the basic tablet had been formed, by either drawing out or blunting one or both ends (cf. Palaima Reference Palaima, Sjöquist and Åström1985, 103).

Fig. 10. Ad 683 recto and lat. inf. Note the tapering right-hand end and the curvature of the verso at both ends. Photos: National Archaeological Museum, Athens/ Department of Collections for Prehistoric, Egyptian, Cypriot and Near Eastern Antiquities. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/ Organization of Cultural Resources Development (H.O.C.RE.D.).

During an autopsy session, Evangelia Kiriatzi observed that the tablets’ surfaces and top and bottom edges had been not merely flattened, but smoothed in a way that resembled the burnishing of pottery, as already remarked on by Greco and Flouda (Reference Greco and Flouda2017, 149–51) based on their studies of tablets from Knossos. In line with the results of Greco and Flouda's experiments, I found that this effect could be achieved using the rounded edge of a wooden clay-shaping tool: wetting the tool made it easy to draw it across the clay surface, producing a smooth finish on the writing surface and edges. The various shapes of smoothed tablet edges – which can be either rounded or flattened, with rounded or slanted edges – could easily be produced by altering the angle and pressure of the tool. Note that this smoothing can produce an appearance very similar to that of an erasure (since it is, effectively, the same process); it is therefore possible that at least some of the tablets identified as palimpsests due to showing ‘erasure’ marks, but which do not preserve any identifiable traces of previously written text, may in fact be showing traces of this smoothing process.

Page-shaped tablets, whether simply flattened or folded, require shaping to form a rectangular tablet rather than one with the curved edges that are naturally produced by flattening a lump of clay. From autopsy observations, page-shaped tablets’ edges were frequently either folded over onto the verso (cf. Bennett Reference Bennett, De Miro, Godart and Sacconi1996, 29) and/or flattened, often sloping onto the verso with a raised area of clay behind them (Fig. 11). Although the page-shaped tablets are often cut on one or two sides to trim off unused clay, like the palm-leaves, and occasionally larger tablets are cut to create two smaller ones,Footnote 48 they are never cut on all four sides to the desired shape.Footnote 49 In experiments I found that the flattened and sloping edges could be produced by squashing the tablet's edge with a flat surface; using a hand-held object such as the side of the rolling pin or a plastic block allowed the angle and pressure to be more easily adjusted than when pressing the clay against the surface it was sitting on. Pressing this object down on the edge of the clay at an angle produced the characteristic straight edge sloping towards the verso, with a ridge of clay pushed up behind it. Both of these methods served to produce rectangular tablets with neater, straighter edges, which could then be further neatened by smoothing the edges and recto as described above.

Fig. 11. Jn 415 verso showing folds and ridges of clay along the bottom edge and sides (the top has been cut). Photo: National Archaeological Museum, Athens/ Department of Collections for Prehistoric, Egyptian, Cypriot and Near Eastern Antiquities. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/ Organization of Cultural Resources Development (H.O.C.RE.D.).

This experimental investigation has thus shed new light not only on the processes involved in creating tablets, but also on the decision-making of the tablet-makers in choosing between those processes, and the ways in which this relates to the next stages of document production and use. In the final section of this paper I shall investigate this last issue further by using a series of case-studies to explore the relationship between the tablets’ makers and writers.

TABLET-MAKERS AND TABLET-WRITERS

No clear connection can be seen between a tablets’ format and/or production method and the identity of their makers, where this is known. As mentioned above, Sjöquist and Åström (Reference Sjöquist and Åström1985, 47–56 and table 1) were able to identify prints (probably) belonging to the same maker on more than one tablet in only four cases:

-

‘Dokimastikos’: Qa 1292, 1294, and 1311 (all H15).

-

‘Energetikos’: at least one Ab series tablet (H21),Footnote 50 at least five Ea series tablets (H43),Footnote 51 at least three Eb series tablets (H41),Footnote 52 and perhaps Eo 268 (H41).

-

‘Mikros’: Ea 801 and 823 (H43), perhaps also Ea 305 (H43) and Aa 94 (H4).

-

‘Anon I(?)’: perhaps Ea 922 (H43) and Eb 477 (H41).Footnote 53

We thus have one instance of the same maker's prints being found on multiple tablets inscribed exclusively by a single writer – ‘Dokimastikos’ in H15's Qa series – where the simplest assumption is therefore that these may be the same person; unfortunately there are no identifiable prints on the three Qa series tablets inscribed by a different writer, H33.Footnote 54 All tablets within this series are similar in format and probably also in production process (they are relatively small and thin palm-leaf tablets, with flat rather than curved versos; at least some of both the H15 and H33 tablets have been made by folding). It is not possible to say whether this is because ‘Dokimastikos’ made all of the tablets regardless of their eventual writer, but looking at the instances of prints being found in multiple series by different writers implies that this assumption is not necessary. No significant differences are visible between the Ea series tablets made by ‘Energetikos’, ‘Mikros’, or ‘Anon I(?)’, or the Eb series of ‘Energetikos’ and ‘Anon I(?)’; nor do tablets from different series showing prints of these makers appear more similar to each other than to other members of the same series.Footnote 55 The Eb series, for instance, consistently contained straws/strings, and although the ‘Anon I(?)’ tablet has a more blunted left-hand end than those attributed to ‘Energetikos’ (which, when not broken, are either rounded or left without neatening), this is a feature which varies considerably both in general and within this series. As far as can be seen, then, variation in tablet format/manufacture does not relate to individual preferences of the tablets’ makers.

Of the writers of tablets with straws/strings, H5 (Sh series), H23 (Ad series), and H26 (Sa series) are not known to have written any other tablets,Footnote 56 but H21, H41 and H42 have all written palm-leaf tablets made both with and without this feature.Footnote 57 As already discussed, it is harder to be certain how consistently tablets have been rolled or folded, but comparing tablets’ size and shape is more straightforward, and again there is no evidence for any preference by writers beyond the needs of the individual texts. For instance, as a fairly crude measure of this, H1's complete palm-leaf tablets range in surface area from 9.9 cm2 (Na 530) to 68.4 cm2 (Ed 236), and page-shaped tablets from 27.7 cm2 (An 199) to 412.8 cm2 (En 74); note the considerable overlap in size between the largest palm-leaves and smallest page-shaped tablets, as well as variation in other aspects of formatting such as the orientation of page-shaped tablets (e.g. the En and Ep landholding series contain both vertical and horizontal tablets). Thus, there is also no clear connection between writer and tablet format or manufacturing method: we are not dealing with consistent preferences on the part of writers any more than that of makers (remembering again that these may often have been the same person).

In fact, even within broad groups of tablets relating to similar topics and written by a single person there is considerable variation. The Fr series, for instance, consists of records of small amounts of olive oil being issued, mostly for religious purposes (to deities or sanctuaries), written by at least six people (H2, H4, H17, H18, H19, H41). Although the texts display a very similar structure – brief descriptions of the type of oil and recipient (e.g. ‘In the territory of Lousos: to the gods: sage-scented: c. 5 litres of olive oil’ [Fr 1226, H2]) – their format varies widely. The writer responsible for the largest number of these texts, H2, has used both one- and two-line palm-leaves, the latter of which may contain one or two entries, of very different sizes (length 8.9–21.5 cm, width 1.9–3.3 cm, thickness 0.9–1.6 cm) to write distribution records, in addition to one small page-shaped tablet for the single record relating to perfume production (Fr 1184). Other writers have mostly also used palm-leaves, but again these vary considerably in size and shape (e.g. H4: tapering; H17: narrow rectangular; H19: rounded, one- and two-line); H18 has the widest variation in this respect (Fig. 12), with tablets including a palm-leaf with a two-line single entry (Fr 1225), a small horizontal page-shaped tablet (Fr 1218), and a rounded three-line tablet which in shape resembles an enlarged palm-leaf but is formatted like a horizontal page-shaped tablet (Fr 1217).Footnote 58 The findspots of these tablets, almost all of which were found in the palace's oil storerooms (Rooms 23, 32, and above Room 38),Footnote 59 suggest that they were created and written on the spot (or in some cases selected from existing tablets which could be re-used)Footnote 60 whenever an issue of oil had to be made: this variation in size, shape and format therefore represents the results of a series of separate decisions made by the tablets’ makers and/or writers to fulfil the recording needs of each separate transaction.

Fig. 12. H18's Fr series tablets. From top to bottom: Fr 1225, 1218, 1217. Photos: National Archaeological Museum, Athens/ Department of Collections for Prehistoric, Egyptian, Cypriot and Near Eastern Antiquities. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/ Organization of Cultural Resources Development (H.O.C.RE.D.).

Where some level of consistency can be seen is within groups of tablets that are not just on the same topic but are closely related in administrative terms – ones that were clearly written as components of a single administrative action and, arguably, collectively form a single ‘file’ of information; this applies to some tablet series and in other cases to sub-groups of series known as ‘sets’. The creation of tablets to specific sizes and formats for specific (sets of) texts, as mentioned above, has frequently been pointed out, and it is often stressed that many tablets appear carefully designed in size and shape for the needs of their particular text, implying at the very least a close collaboration between maker and writer, if not a shared identity (e.g. Palaima Reference Palaima, Sjöquist and Åström1985, 101; Reference Palaima, Duhoux and Davies2011, 84–5; Del Freo Reference Del Freo, Freo and Perna2019, 173; LSP, 15). An examination of the Pylos personnel tablets shows, however, that the details of tablet design can go beyond the demands of the particular text and speak to the individual preferences or choices of the tablets’ maker and/or writer.

We have already seen that the Aa, Ab and Ad series, while representing separate administrative recording actions, are closely linked by their references to the same or related groups of workers: work-groups of women and children in Pylos and the Hither Province, designated by their occupation or place of origin, are recorded by H1's Aa series and by H21's Ab series, which also records their monthly rations (as the numbers differ slightly these two series were presumably not written at the same time); similar work-groups in the Further Province are recorded by H4's Aa series, without corresponding ration records; and H23's Ad series records men and boys in both provinces who are related to the women of the Aa and Ab series. The following example of three related Hither Province texts, plus one Further Province Aa series text, shows their similarity in structure and content:

-

‘21 Knidian women, 12 girls, 10 boys, one male supervisor(?), one female supervisor(?)’Footnote 61 (Aa 792, H1, Hither Province)

-

‘At Pylos: 20 Knidian women, 10 girls, 10 boys: 640 l. figs, 640 l. grain; female supervisor(?), male supervisor(?)’ (Ab 189, H21, Hither Province)

-

‘At Pylos: sons of Knidian women: five men, four boys’ (Ad 683, H23, Hither Province)

-

‘textile decorators: 12 women, 16 girls, eight boys, one male supervisor(?), one female supervisor(?)’ (Aa 85, H4, Further Province)Footnote 62

The textual variations which occur do so for both administrative reasons (the Ab series contains additional ration information; the Ad series work-groups do not include supervisors) and due to writers’ differing choices about how to present the information; the latter are comparatively minor (H1 does not specify the workers’ location when they are at Pylos, unlike H21 and H23; H1 and H4 include numerals for the supervisors while H21 does not). However, in format they are entirely different (Fig. 13) – even H1's and H4's Aa series tablets are strikingly dissimilar, with H4 using extremely long tablets (mean length 23 cm, mean height 2.5 cm), while H1's are much shorter and wider (mean length 14.6 cm, mean height 2.8 cm; in both cases, at least some of the tablets have been folded). That these differences reflect preferences of the writers rather than the tablet-makers (or, if those are the same people, preferences based on writing practices rather than on the process of tablet production) is shown by the way they correspond to differences in the writing of the text – H4's signs are written much larger and are more spaced-out than H1's – as well as the fact that nearly all of H1's tablets are cut after writing to remove excess clay; this writer therefore had extra space they chose not to fill. Meanwhile, the Ab series (at least some of which, again, were folded) falls mid-way between the two Aa sets in terms of length (mean 17.4 cm), despite having more content to include (the details of rations); H21 chose to do this by ruling a short line at the right-hand end of each tablet to create a two-line space to record the rations (and supervisors), a peculiarity of this series which makes what is presumably the most important part of these records stand out clearly (an effect generally achieved by other writers through spacing out the ideograms and numerals, e.g. frequently in both H1's and H4's Aa series). As discussed above, the Ad series is the only one to include straws/strings (intermittently, and with no clear pattern relating to content or size); these tablets are nearly as long as H4's Aa series (mean length 21.7 cm) and even taller than H1's (mean height 3.3 cm).Footnote 63 This group of related texts therefore suggests a highly individual, even idiosyncratic set of preferences for tablet manufacture and formatting on the parts of their makers and/or writers.

Fig. 13. Personnel tablets. From top to bottom: Aa 792 (H1), Aa 85 (H4), Ab 189 (H21), and Ad 683 (H23). Photos: National Archaeological Museum, Athens/ Department of Collections for Prehistoric, Egyptian, Cypriot and Near Eastern Antiquities. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/ Organization of Cultural Resources Development (H.O.C.RE.D.).

However, we can also see consistency within a single administrative ‘file’ where that includes texts written by more than one person. The Qa series, produced by two different writers whose fairly distinctive tablets are physically indistinguishable, has already been discussed above; the Jn series of page-shaped bronze allocation records, written by H2 and H21, similarly shows no significant differences in tablet manufacture or format between the two writers (cf. LSP, 15–16), or between the different stages of the administrative process (finished tablets, works-in-progress, and discarded tablets) which can be identified within this series.Footnote 64 Whether this means in each case that all of the tablets were made by the same person, that two (or more) makers followed a common set of instructions from the writer(s), or that the two writers made their own tablets in accordance with a shared idea of the appropriate way to create them for this particular purpose remains unknown.

Conversely, in the landholding tablets referring to the site of pa-ki-ja-ne (including H41's preliminary Eb and Eo series; H1's summary En and Ep series; and the totalling Ed series, with contributions by both writers: see Footnote n. 7), we see notable differences in format and production between and even within series of tablets referring to the same location and written by the same person.Footnote 65 Sometimes this is clearly due to administrative reasons: H41's use of a mixture of palm-leaf and page-shaped tablets in the Eo series, compared to their consistent use of palm-leaf tablets in the Eb series, is due to the former including several cases of the same person leasing several plots, each recorded on a single page-shaped tablet (H43 has made a similar administrative choice in writing a single page-shaped tablet, Ea 59, to record multiple landholdings held by the same individual, in a series otherwise consisting entirely of palm-leaves). At other times, this variation may provide evidence for the process followed by the writer, including changes to their preferences or decisions in the course of compiling the ‘file’ of documents. The variation in size and format of H1's page-shaped tablets (whose surface areas range from 92.6 cm2 to 412.8 cm2) is evidently partly related to the number and length of entries to be recorded on each tablet, but may also reflect a changing process of recording: Bennett (Reference Bennett, Heubeck and Neumann1983, 44–7) argued that the variation between vertical and horizontal orientations in the Ep series is due to the writer switching from the former (Ep 301, 613) to the latter (Ep 705, 212, 539, 704 – in the order suggested by Bennett) in order to better accommodate this series’ relatively long entries. Similarly, we have already seen that the inconsistent use of straws/strings in the Eo series is difficult to explain on the basis of the tablets’ clay, size and shape, or potential place of writing; could this be due to the situation changing between making the tablets with straws/strings and those without (or vice versa) – which might have been done at different times – or simply to the maker or writer changing their mind about this series’ requirements?Footnote 66 Although reconstructing the circumstances in which particular tablet series were created and written, and the precise factors underlying the makers’ and writers’ decisions in doing so, is generally not possible, considering questions like this reminds us of the potential complexity of different, possibly changing situations in which even those groups of tablets we now regard as relatively consistent series might have been produced.

CONCLUSIONS

This experimental investigation into the various methods used to produce the Linear B tablets at Pylos has shed significant light on the effects of these methods on the tablets, and thus on the probable reasons behind tablet-makers’ choices of different methods in different circumstances. In particular, creating a tablet by folding up a sheet of clay has been shown to provide increased stability while the clay remains relatively wet – an advantage if the tablet is being handled and/or written on at this stage – while the primary benefit of using a straw/string is in keeping fragments together if the tablet is broken in transit. These results demonstrate that consideration for both the experience of the tablet's future writer (whether that writer was also its maker or not) and for the further administrative processes the tablet would undergo (such as transportation to or within the palace) played a part in the tablet-makers’ decisions as to what process(es) to use when creating a tablet.

However, investigating the relationship between tablets’ production processes and contents in the light of these results has also shown that these decisions are frequently very difficult to reconstruct for any given tablet or group of tablets. Tablet-makers’ and/or writers’ preferences for how tablets were made (and written on) are highly individual, and not always based purely on clearly reconstructable administrative reasons. Although the administrative unity of groups of texts which collectively record a single operation is frequently also shown in their format and/or production process – regardless of how many people were involved in their making and/or writing – these individual idiosyncrasies, together with the potential for circumstances to alter or for makers or writers simply to change their minds, frequently create a more complicated situation. What this reinforces, though, is that the relationship between the making and writing stages of the process was a very close one, as demonstrated by the consistency in tablet production in cases where palm-print evidence shows the involvement of multiple makers, compared to instances where this process changes across a series of documents in accordance with the writer's administrative needs. Regardless of the identity of a tablet's maker in any given case – most likely in some instances writers made their own tablets, while in others this was done by another writer or an assistant – careful consideration of the needs of the writer was inherent in the production of a tablet as the first stage of the Mycenaean administrative recording process.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was carried out during a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions fellowship at the British School at Athens, as part of the project ‘Writing at Pylos (WRAP): palaeography, tablet production, and the work of the Mycenaean scribes’. This project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 885977. I would like to thank the staff of the National Archaeological Museum, Athens, in particular Katerina Voutsa, for facilitating access to the Pylos tablets; the staff of the Fitch Laboratory, especially Evangelia Kiriatzi, for providing experimental facilities and advice; and John Bennet and the two anonymous reviewers for their comments.