Childhood Fe deficiency is a common nutritional problem affecting some 50–60 % of children aged 6–60 months in various regions of Pakistan(Reference Huma, Ur-Rehman and Anjum1). The consequences of childhood Fe deficiency include anaemia, reduced work capacity, decreased growth rate, impaired motor development and reduced intelligence quotient scores(Reference Kordas2). Fe deficiency is particularly common in the first 2 years of life as children are often weaned on to Fe-deficient diets(Reference Lynch and Stoltzfus3). During dietary Fe deficiency, increased absorption of other trace metals such as Pb may occur as they often compete with Fe for the same transporters in the mucosal wall(Reference Gunshin, Mackenzie and Berger4).

Mn is an essential trace element and a component of several enzymes including superoxide dismutase. Adults exposed to toxic concentrations of Mn often develop manganism, a neurological condition displaying symptoms similar to Parkinson's disease. Additionally, children exposed to Mn have higher blood and hair concentrations and suffer from a decline in intellectual function(Reference Riojas-Rodriguez, Solis-Vivanco and Schilmann5). Exposure to Mn occurs in steel manufacturing, welding and mining of Mn ores, and is due to inhalation of Mn-containing dust and fumes(Reference Donaldson6). Mn is also used in the battery, glass and ceramics industries and is a component of certain pesticides(Reference Mergler7). Excessive provision and accumulation of Mn have also been reported in patients receiving total parenteral nutrition, where cholestasis restricts its excretion(Reference Alves, Thebot and Tracqui8). Mn is present in high concentrations in tea and excessive tea consumption has been associated with its toxicity(Reference Ross, O'Reilly and McKee9).

An increased absorption of Mn in Fe-deficient subjects may account for the fivefold increase in blood Mn observed in anaemic individuals aged between 13 and 44 years(Reference Mena, Horiuchi and Burke10). Strong evidence exists that Fe and Mn compete for absorption into the mucosal cells(Reference Rossander-Hulten, Brune and Sandstrom11). This absorption has been attributed to the divalent metal transporter protein-1 (DMT1) which is a common transporter for both Fe and Mn(Reference Fitsanakis, Zhang and Avison12). However, transferrin, the major transport protein for Fe, has also been implicated in the transport of Mn(Reference Davidson, Lonnerdal and Sandstrom13). Another study conducted in adults showed those with Fe-deficiency anaemia had significantly higher concentrations of blood Mn compared with controls(Reference Kim, Park and Choi14). However, all of these previous studies investigating the relationship between Fe deficiency and blood Mn are either in adults or children over 13 years of age. In the present study, we looked at a much younger age group (6–60 months) as these children are more likely to suffer from Fe deficiency. Furthermore, we conducted our study in Pakistan, which has a high incidence of Fe deficiency and where there is very little information on blood Mn in children and none on its relationship with Fe status. The present study investigated blood Mn concentrations in children from Karachi who were categorized into four groups depending on the severity of their Fe deficiency: normal, borderline Fe deficiency, Fe deficiency and Fe-deficiency anaemia. In the past, many studies determined Fe status using ferritin as a marker. However, it is well known that ferritin concentrations increase in individuals with an acute-phase reaction, as in inflammation, irrespective of Fe status and thus need to be interpreted with caution or supported by markers not influenced by acute-phase reactions such as measurements of soluble transferrin receptors (sTfR). Indeed, in the present study, Fe status was determined using WHO criteria and supported by measurements of sTfR, a sensitive indicator of early Fe deficiency.

Materials and methods

The study received approval from the Ethics Committees of Kharadar General Hospital, Civil Hospital and Liaquat National Hospital, all in Karachi, Pakistan, as well as the Ethics Committee at Manchester Metropolitan University, UK. The minimum number of children required for each group of Fe status was determined by power analysis using the UCLA Department of Statistics Power Calculator. This has been determined for expected differences for blood values for Mn.

Study population

A total of 506 children aged 6–60 months were selected and screened for their Fe status at paediatric outpatient departments of Karachi Civil Hospital (n 278), Kharadar General Hospital (n 73) and Liaquat National Hospital (n 155). The height and weight of each child were recorded. A questionnaire was used to collect the following information from parents (usually the mother): name of child, sex, age, clinical history, diet up to 24 months of age, any Fe supplementation, family income (in Pakistani rupees; <Rs 6000; Rs 6001–10 000; Rs 10 001–20 000; >Rs 20 000) and parental education (none; primary; secondary; intermediate and above). Parents were informed of the study in layman's terms in their native language. Informed consent was obtained from the parents in writing prior to any collection of blood specimens from children.

Specimen collection

Non-fasting blood (5 ml) was collected by a trained phlebotomist; 1 ml was transferred into a lithium heparin tube for blood Mn determination, 1 ml was transferred into an EDTA tube for a full blood count and 3 ml was transferred to a tube with a blood clotting gel for the remaining tests (C-reactive protein (CRP), bilirubin, Fe, ferritin and sTfR). All specimens for haematology, CRP and Zn protoporphyrin were analysed immediately in duplicate, whereas blood samples for Mn analyses were stored at −70°C. A stool specimen was collected from each child for hookworm analysis.

Exclusion criteria

Children with a birth weight less than 2·5 kg, those on parenteral nutrition and those suffering from malignancy, renal disease, any acute/chronic illness or major congenital or perinatal complications were excluded, as was any child who had been hospitalized in the previous six months or was receiving any form of Fe supplementation or total parenteral nutrition.

It is well known that certain conditions can affect Fe status/Mn and thus need to be excluded. For example, the acute-phase response can affect markers of Fe status such as ferritin whereas malignancy and renal disease can both cause anaemia. Similarly, children receiving total parenteral nutrition are susceptible to cholestasis and thus may suffer from decreased excretion of Mn and a build-up of its blood concentration.

Furthermore, any child who tested positive for hookworm infections following stool analysis was also excluded. Those children who were not in these categories had their blood analysed and those with a CRP measurement >6 mg/l or cholestasis (conjugated bilirubin >10 μmol/l) were also excluded from the study.

Biochemical tests

Biochemical tests were performed using automated analyses and kit methods. These methods had undergone routine evaluation and quality controls were used with every batch of specimens. Results for a batch were accepted only when controls were within their acceptable limits.

C-reactive protein

This was determined within an hour of sample collection using the Tina-quant CRP (Latex) immunoturbidimetric assay (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland).

Bilirubin

Total bilirubin and direct bilirubin were determined using a kit method based on the colorimetric reaction of bilirubin with a diazo reagent (Roche Diagnostics).

Full blood count

A full blood count was determined by automated analysis using a haematology analyser (Nihon Kohden, Tokyo, Japan) and included measurement of red blood cell count (RBC), white blood cell count (WBC), Hb, haematocrit, mean cell haemoglobin (MCH), mean cell haemoglobin concentration (MCHC) and mean cell volume (MCV).

Iron status

Serum Fe was determined using a kit method based on the colorimetric reaction of Fe with FerroZine (Roche Diagnostics). Total iron binding capacity (TIBC) was determined using a colorimetric kit method (Randox Laboratories, Crumlin, UK) and transferrin saturation was calculated using the formula:

Serum ferritin was measured using the Tina-quant ferritin immunoturbidimetric kit method (Roche Diagnostics).

Soluble transferrin receptors

This was performed manually using the human sTfR ELISA kit method (BioVendor GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany). The standards, controls and samples made up to a volume of 100 μl were incubated in a microplate at 30°C with shaking. All the wells were then washed three times with wash solution before adding 100 μl of conjugate solution (anti-sTfR antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase) to each well. The microplates were incubated at 37°C for a further hour with shaking before the wells were washed again three times with wash solution. The substrate solution (tetramethylbenzidine) was added (100 μl) to each well followed by 10 min incubation at room temperature. Colour development was stopped by addition of 100 μl of stop solution (0·2 m-H2SO4) and the absorbance at 450 nm was read within 5 min using a microplate reader (ELIZA MAT-3000; DRG Instruments GmbH, Marburg, Germany).

Classification of iron status

Children were divided into four groups of Fe status based on the WHO criteria as described in Table 1 and blood Mn was then determined in each of these four groups.

Table 1 The WHO criteria for classification of children into normal iron status, borderline iron deficiency, iron deficiency and iron-deficiency anaemia

MCV, mean cell volume; MCH, mean cell haemoglobin.

Blood manganese

Blood Mn was determined at the PCSIR (Pakistan Council for Scientific and Industrial Research) Laboratories, Karachi, Pakistan. Mn standards were prepared using Spectrosol manganese solution (BDH, Poole, UK) and Seronorm™ whole blood trace element controls (SERO AS, Billingstad, Norway) were used for quality control purposes. Whole blood or standards (50 μl each) were mixed with 350 μl of diluent (25 μl Triton X-100 and 25 μl of antifoam B emulsion made up to 50 ml in sterile distilled water) in 1·9 ml acid-washed metal-free microcentrifuge tubes before being transferred into acid-washed auto-sampler cups and loaded onto the auto sampler for analysis using a Zeeman-background-corrected flameless atomic absorption method with a graphite furnace (model Z-8100; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Minitab 16 statistical software. Depending on distribution (Anderson–Darling and Kolmorogov–Smirnoff tests), data are presented as mean with standard deviation or as median with interquartile range and were analysed using the t test/ANOVA if normally distributed or the Mann–Whitney/Kruskal–Wallis test if a non-normal distribution. Differences between groups were analysed by converting the data to a normal distribution (if necessary) and using the Tukey post hoc test. Data were correlated with Pearson's or Spearman's method depending on distribution. Multiple regression analysis was used with blood Mn as the dependent variable and factors of Fe status as independent variables. Results were considered significant when P < 0·05.

Results

Participants’ characteristics

A total of 506 children were screened of whom 269 met the inclusion criteria. These included 113 females (42 %) and 156 males (58 %). The age range of these children was 6–60 months and their mean age was 28·1 (sd 12·5) months (n 269). The mean height of these children was 82·3 (sd 14·1) cm (n 257) and their mean weight was 11·1 (sd 6·2) kg (n 257). A total of 237 children were excluded from the study, twenty-four of whom had a CRP measurement in excess of 6 mg/l and faecal samples from two tested positive for hookworm. Basic information on the gender of these children, and their families’ ethnic background, education and income, is outlined in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 Participants’ gender and the ethnic background, language spoken, education and monthly income (in Pakistani rupees, Rs) of their families: children (n 269) aged 6–60 months from low-income families, Karachi, Pakistan

Blood Mn in children of different ages

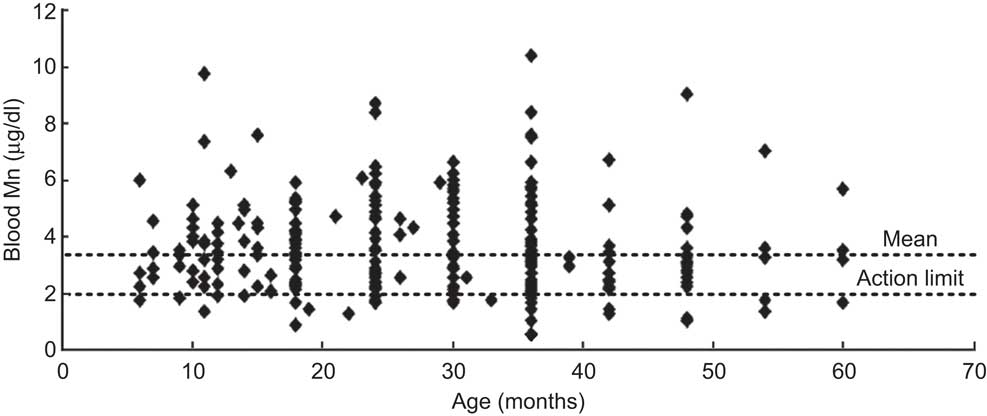

The blood Mn concentrations in children of different ages are shown in Fig. 2. The mean blood Mn concentration for the children included in the study was 3·7 (sd 1·6) μg/dl (n 269) and the highest concentrations were found in children in the age range 19–24 months, where the mean was 4·0 (sd 1·8) μg/dl (n 43).

Fig. 2 Scatter plot showing concentrations of blood Mn in the participants according to age: children (n 269) aged 6–60 months from low-income families, Karachi, Pakistan. Mean blood Mn concentration is 3·7 (sd 1·64) μg/dl (n 269) whereas the action limit for Mn is >2·0 μg/dl

Blood Mn in children according to Fe status

Multiple regression analysis showed a weak relationship between Fe and blood Mn (Table 2). The adjusted r 2 value showed that the model could explain only 15 % of blood Mn results. In the present analysis, the only independent relationship was Mn with TIBC. In a stepwise regression analysis, ferritin and TIBC had the most significant relationship with Mn (P < 0·001).

Table 2 Coefficient results for multiple regression analysis with blood manganese as the dependent variable and factors of iron status as independent variables: children (n 269) aged 6–60 months from low-income families, Karachi, Pakistan

MCV, mean cell volume; MCH, mean cell haemoglobin; MCHC, mean cell haemoglobin concentration; TIBC, total iron binding capacity.

Blood Mn concentrations were determined following classification of the children into four groups using the WHO criteria, as shown in Table 3. Measurements of sTfR confirmed the Fe deficiency and were a good discriminator of different groups of Fe status. Indeed, children with Fe-deficiency anaemia had higher sTfR concentrations than those with borderline Fe deficiency or normal Fe status (P < 0·05). Children with Fe deficiency and borderline Fe deficiency had higher concentrations of sTfR compared with those of normal Fe status (P < 0·05).

Table 3 Blood manganese and sTfR concentrations by categorization into normal iron status, borderline iron deficiency, iron deficiency and iron-deficiency anaemia according to the WHO criteria: children (n 269) aged 6–60 months from low-income families, Karachi, Pakistan

sTfR, soluble transferrin receptors.

*P < 0·001 overall. Concentration of sTfR was higher in children with Fe-deficiency anaemia compared with those with borderline Fe deficiency or normal Fe status (both P < 0·05). Concentration of sTfR was higher in children with Fe deficiency and borderline Fe deficiency compared with those of normal iron status (P < 0·05).

†P < 0·01 overall. Blood Mn was higher in children with Fe-deficiency anaemia and Fe deficiency compared with those with normal Fe status (P < 0·01).

The median blood Mn concentrations in children with Fe-deficiency anaemia and Fe deficiency were both significantly higher than in the group of children of normal Fe status (P < 0·01). The median blood Mn concentration in children with Fe-deficiency anaemia was also significantly higher than that of children with borderline Fe deficiency (P < 0·01).

Haematological parameters of children according to Fe status

Most haematological parameters and indices of Fe status showed a significant relationship (P < 0·001) in children with different Fe statuses (Table 4). However, there was no significant difference in RBC among children according to Fe status.

Table 4 Haematological parameters, presented as means and standard deviations, in children of normal iron status (n 68), borderline iron deficiency (n 46), iron deficiency (n 42) and iron-deficiency anaemia (n 113): children (n 269) aged 6–60 months from low-income families, Karachi, Pakistan

RBC, red blood cell count; WBC, white blood cell count; MCV, mean cell volume; MCH, mean cell haemoglobin; MCHC, mean cell haemoglobin concentration.

Discussion

The concentrations of blood Mn in children of normal Fe status found in the present study agree with those published recently for children from Hyderabad in Pakistan, where blood Mn concentrations of 2·95 (sd 0·75) μg/dl (n 186) were reported in male and 3·12 (sd 0·53) μg/dl (n 174) in female children 3–7 years of age(Reference Afridi, Kazi and Kazi15). These values in Pakistan are higher than the value of 1·28 (sd 0·37) μg/dl (n 95) reported in 10-year-old Bangladeshi children(Reference Wasserman, Liu and Parvez16). Indeed, these values are higher than the reference range for blood Mn of 0·4–1·2 μg/dl quoted in the UK(Reference Taylor17). In our study the mean concentration of blood Mn in children of normal Fe status and the mean of all children are higher than the action limit of 2·0 μg/dl for blood Mn quoted by the SupraRegional Assay Service for Trace Elements in the UK. Concentrations of blood Mn above the action limit can be treated using EDTA chelation therapy which increases urinary excretion of Mn, thereby reducing blood Mn concentrations(Reference Crossgrove and Zheng18). Previous studies in other parts of the world such as Bangladesh have demonstrated increased Mn content of drinking water and suggested that this may cause intellectual impairment in children(Reference Wasserman, Liu and Parvez16). There is limited information on Mn content of drinking water in Pakistan but at least one study conducted in the Southern Sindh region of Pakistan reported water Mn levels within limits posed by the WHO(Reference Memon, Soomro and Akhtar19). There has been concern with use of the fuel additive methylcyclopentadienyl manganese tricarbonyl (MMT), which releases Mn as airborne sulfates and phosphates(Reference Pfeiffer, Roper and Dorman20). However, other studies have not been able to demonstrate an increase in environmental or blood Mn with use of MMT(Reference Gulson, Mizon and Taylor21). Another possible source of increased blood Mn in young children is from the mother's milk, particularly if they are residents of Mn-contaminated areas. However, the most likely source of Mn pollution is industrial as there are a large number of industries in Karachi. These include the steel and metallurgy industries, chemical refineries, and pesticides, electronics and pharmaceutical industries, in addition to automobile and battery repair workshops. However, the precise source of this Mn in Karachi is not known.

In the current study, children were classified into different groups of Fe status using WHO criteria and supported by sTfR measurements. The WHO criteria included measurement of serum ferritin, which is a good indicator of Fe deficiency in the early stages. It also reflects stored Fe which is the first to decline during a deficiency. However, ferritin measurements have to be interpreted with caution as it is an acute-phase reactant that increases during inflammation. Therefore CRP measurements are necessary to exclude individuals with inflammatory conditions(Reference Wang, Knovich and Coffman22). Measurements of Hb, MCV and MCH are good indicators of severe or Fe-deficiency anaemia. Measurements of sTfR represent the functional Fe compartment, are best for detection of early Fe deficiency and are not influenced by inflammatory conditions(Reference Beguin23). Thus our approach of using both WHO criteria and sTfR measurements provides a more robust determination of Fe status.

Blood Mn concentrations were higher in children with Fe-deficiency anaemia and this may be due to increased absorption of Mn in the gastrointestinal tract during dietary Fe deficiency. Indeed, it has been demonstrated that both Fe and Mn compete for the same transporter, i.e. DMT1, thus a deficiency in Fe causes increased transport of Mn not only into the blood but also across the blood–brain barrier(Reference Fitsanakis, Zhang and Garcia24). Indeed Fe-deficiency anaemia is associated with increased expression of duodenal DMT1(Reference Byrnes, Barrett and Ryan25). During lack of dietary Fe, there may be increased uptake of Mn instead; hence the high blood Mn concentrations in children suffering from Fe-deficiency anaemia.

Young children aged 18–24 months often suffer from Fe deficiency and this may account for the higher concentrations of blood Mn in this age group of children. The high incidence of Fe deficiency in these children is because they are often weaned on to cow's milk after 12 months of age, which contains insufficient Fe. Another reason for Fe deficiency is lack of consumption of Fe-rich foods such as red meat in children of low socio-economic status. Furthermore, they may start to consume foods such as chapatti that contain phytates which are known to reduce absorption of dietary Fe, thus leading to Fe deficiency(Reference Tupe, Chiplonkar and Kapadia-Kundu26). This should allow for greater absorption of Mn as it competes with Fe. However, this process is complicated by the fact that Mn too is chelated by phytates although the extent of this relative to Fe is unclear.

The major target for Mn toxicity is the brain, where it deposits primarily in the globus pallidus but also in the nigra para reticularis. Subsequently, Mn is also deposited in other areas such as the striatum, pineal gland olfactory bulb and substantia nigra pars compacta(Reference Fitsanakis, Zhang and Avison12). MRI can be used to monitor deposition of Mn in the brain(Reference Fitsanakis, Zhang and Avison12). Deposition of Mn in the brain produces neurotoxicity and symptoms similar to Parkinson's disease. However the two are distinct in the sites affected and the clinical symptoms produced(Reference Crossgrove and Zheng18). Although manganism has only been shown in adults, the effect of Mn toxicity on child development and behaviour is of concern in young children as they absorb more Mn from the diet compared with adults(Reference Winder27). Thus children are more likely to suffer Mn toxicity if they are Fe deficient. Indeed, toxic effects of Mn on intellectual impairment have been reported in 6–13-year-old children who were exposed to Mn from tap water(Reference Bouchard, Sauve and Barbeau28). A tenfold increase of Mn in tap water was associated with a decline in intelligence quotient of 2·4 points in these children. Another study in children aged 1–2 years showed that Mn was an essential nutrient but toxic at high levels in young children, affecting neurodevelopment(Reference Claus Henn, Ettinger and Schwartz29).

Conclusion

Childhood Fe deficiency is a common nutritional problem in Pakistan; it is associated with poor dietary intake of Fe and affects children from families of lower socio-economic status. The present study reports for the first time high concentrations of blood Mn particularly in children with Fe deficiency residing in Karachi. The consequences of chronic exposure to Mn are severe and thus the sources of Mn pollution need to be identified. There is therefore a need not only to reduce environmental Mn pollution, but also to consider approaches such as Fe fortification of foods aimed at correcting Fe deficiency in young children.

Acknowledgements

Sources of funding: The authors are grateful to the Nestlé Foundation for a project grant which allowed them to undertake the study. Conflict of interest: None of the authors report any conflict of interest. Authors’ contributions: N.A. and M.A.R. designed the study, analysed the data and wrote the paper. B.R. performed the research and analysed the data. Acknowledgements: The authors are grateful to Dr Arshalooz Rehman and Dr Ghulam Murtaza for their assistance with recruitment of patients and collection of blood specimens in Karachi and to Dr Andrew Blann from the City Hospital, Birmingham, UK for his help with the statistical analysis.