Mental illnesses, including depression, anxiety, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, are widely prevalent across the globe. In Canada, one in five individuals are affected by mental illness every year, and it remains one of the leading causes of disability in Canada(Reference Caron and Liu1,Reference Lang, Alam and Cahill2) . Mood and anxiety disorders in particular have continued to drastically rise in prevalence in Canada within the past decade(Reference Palay, Taillieu and Afifi3). Mental illnesses have detrimental impacts on quality of life, commonly equivalent or greater than that of other illnesses(Reference Defar, Abraham and Reta4), through an impact on social support, marital status, occupation and disability. With this increase in mental illness and its substantial impact, there is a need for more research that targets not only treatment options for mental illness but also preventative measures that reduce the global burden of disease.

There is currently abundant research demonstrating the positive effect of the Mediterranean diet on physical health. The Mediterranean diet has been known to have substantial benefits on the prevention of cancer, CVD and metabolic disease(Reference Serra-Majem, Roman and Estruch5). Other studies found that the Mediterranean diet reduces the risk of Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease and overall mortality(Reference Sofi, Cesari and Abbate6). There is also emerging evidence that it may protect against the development of mental health disorders, as demonstrated by multiple prospective cohort studies(Reference Molendijk, Molero and Ortuño Sánchez-Pedreño7). The Mediterranean diet is rich in fruits, vegetables, nuts, fish, white meat and unsaturated fats, namely olive oil. It has also been highly regarded as a palatable and sustainable diet(Reference Psaltopoulou, Sergentanis and Panagiotakos8). Clinical trials using the Mediterranean diet have demonstrated the ability to significantly reduce depressive symptoms(Reference Firth, Marx and Dash9). One systematic review of observational studies found that higher adherence to the Mediterranean diet was associated with lower rates of Axis I disorders (depression, anxiety, bipolar disorders, schizophrenia, psychosis, eating disorders, obsessive–compulsive disorders, trauma and stress-related disorders, substance abuse and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder), with the lowest rates seen in depression and anxiety(Reference Madani, Ahmadi and Shoaei-Jouneghani10). Although the evidence is mounting for a protective and therapeutic effect of the Mediterranean diet on mental health, it is not fully understood how each of the individual components of this diet contributes to this benefit.

Olive oil, a staple in the Mediterranean diet, is mainly composed of oleic acid (an omega 9 [n-9] fatty acid), and oleuropein, a phenolic compound that gives olives their bitter taste(Reference Haris Omar11). It makes up 20–25 % of the total energy intake in the traditional Mediterranean diet(Reference Martínez-González, Sayón-Orea and Bullón-Vela12). Olive oil is known to have a beneficial association with cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes and all-cause mortality(Reference Martínez-González, Sayón-Orea and Bullón-Vela12). Specific compounds in olive oil, such as oleocanthal, oleacein and oleuropein, have been found to be directly associated with reduced risk of cancer due to their anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties(Reference González-Rodríguez, Ait Edjoudi and Cordero-Barreal13,Reference Papakonstantinou, Koumarianou and Rigakou14) . Another study observed significant reductions in oxidative stress biomarkers associated with the high phenolic content of olive oil, providing further support for its antioxidant effects(Reference Derakhshandeh-Rishehri, Kazemi and Shim15). One study found significant reductions in symptoms associated with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, specifically due to the anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects of polyphenols in olive oil(Reference Santangelo, Varì and Scazzocchio16). Inflammation and oxidative stress have both been proposed as mechanisms which mediate the impact of diet on mental health(Reference Marx, Lane and Hockey17); these mechanisms might explain how olive oil could benefit mental health. To date, the effect of olive oil consumption on mental health has not been thoroughly studied. Due to the limited experimental research and no prior synthesis on the effects of olive oil on mental health, a scoping review is warranted. The objective of this scoping review is to systematically search for and synthesise the research on olive oil and mental health.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

The following eligibility criteria were applied.

Inclusion criteria:

-

Human experimental or observational studies, animal studies and meta-analyses.

-

Delivery of olive oil or one of its constituents (oleic acid and oleuropein) or assessment of intake of olive oil or measurement of tissue levels of constituents.

-

Assessment of any mental health outcome (incidence of mental disorder, severity of mental disorder, treatment or progression of a mental disorder). Eligible mental disorders included: depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, psychotic disorders, bipolar and related disorders, obsessive–compulsive and related disorders, attention-deficit disorders, trauma- and stressor-related disorders, substance use disorders and eating disorders. Any year of publication, language or publication status.

Exclusion criteria:

-

Narrative reviews, editorials or opinion articles.

-

Delivery or assessment of olive oil in combination with other fatty acids, nutrients or foods

-

Assessment of neurodegenerative disorders.

Information sources and search strategy

PubMed and OVID MEDLINE databases were searched on 10 November 2023. The following search strategies were used. No filters or limits were used.

PubMed: (Olive oil OR (“Oleic Acid”[Mesh]) OR “Olive Oil”[Mesh] OR n-9 OR Oleuropein) AND (“Anxiety”[Mesh] OR “Anxiety Disorders”[Mesh] OR depression OR “Depressive Disorder”[Mesh] OR “Depression”[Mesh] OR mental health OR psychiat* OR mental illness)

OVID Medline: (Olive oil or n-9 or oleuropein) and (anxiety or anxiety disorder or depression or depressive disorder or mental health or psychiat* or mental illness)

Record screening and selection

Titles and abstracts were screened independently in duplicate by the two authors using the eligibility criteria. The program Abstrackr(Reference Gates, Johnson and Hartling18) was used for organisation. In cases of disagreement, the authors discussed the study until consensus was reached. Studies were then reviewed in full text to confirm eligibility.

Data collection process and data items

Data were extracted using piloted templates. Extraction was completed by one author and checked by the second author. The data extracted included: study design, participant/subject population, sample size, intervention or exposure (including duration), outcome and results.

Data analysis

Data were analysed qualitatively to assess trends and gaps for further study.

Results

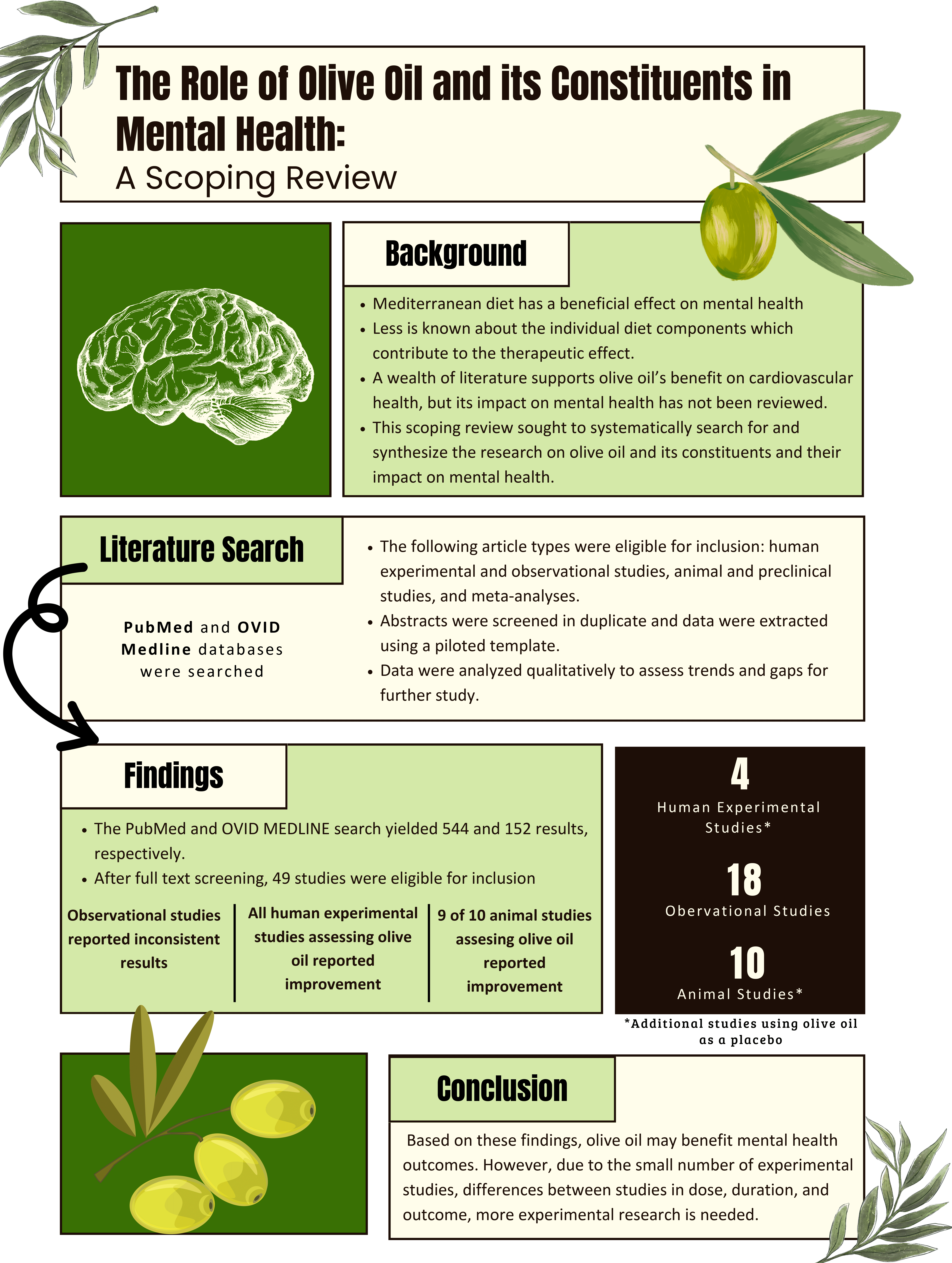

The PubMed and OVID MEDLINE search yielded 544 and 152 results, respectively (Fig. 1). After deduplication, 552 results remained. After full-text screening, forty-nine studies were eligible for inclusion, including seventeen human experimental, eighteen observational and fourteen animal studies. Of the studies found, thirteen human intervention studies and four animal studies were designed to assess the impact of a different intervention on mental health outcomes and used olive oil as the comparator. Four human intervention studies that were designed to assess the impact of olive oil on mental health were identified (Table 1)(Reference Foshati, Ghanizadeh and Akhlaghi19–Reference Mitsukura, Sumali and Nara22). All four were randomised controlled trials. Sample size ranged from seventeen to 129 and duration ranged from three to 12 weeks. The patient populations involved included people with major depressive disorder, fibromyalgia, obesity and healthy subjects. All four studies reported an improvement in mental health outcomes, including symptoms of depression(Reference Foshati, Ghanizadeh and Akhlaghi19,Reference de Sousa Canheta, de Souza and Silveira21) , anxiety(Reference de Sousa Canheta, de Souza and Silveira21), stress(Reference Mitsukura, Sumali and Nara22) and overall mental health status(Reference Rus, Molina and Ramos20).

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram.

Table 1. Intervention studies designed to assess the impact of olive oil supplementation

EVOO, extra virgin olive oil; MDD, major depression disorder; BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory II; HAMD-7, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale 7; MCS-12, Mental Component Score 12; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

Eighteen observational studies met criteria for inclusion (Table 2)(Reference Vučković, Radić and Gelemanović23–Reference Ford, Jaceldo-Siegl and Lee40). Twelve studies were cross-sectional in design and of these, five assessed olive oil intake using a self-reported diet data collection instrument(Reference Vučković, Radić and Gelemanović23–Reference Bertoli, Spadafranca and Bes-Rastrollo27) while seven measured tissue levels of oleic acid(Reference Cocchi and Tonello28–Reference Sumich, Matsudaira and Heasman34). The six prospective studies assessed olive oil or oleic acid intake(Reference Leone, Martínez-González and Lahortiga-Ramos35–Reference Ford, Jaceldo-Siegl and Lee40). Of the six prospective studies, five reported an association between higher baseline olive oil intake and lower risk of developing a mental health disorder or symptoms at a later time point(Reference Leone, Martínez-González and Lahortiga-Ramos35,Reference Kyrozis, Psaltopoulou and Stathopoulos36,Reference Sánchez-Villegas, Verberne and De Irala38–Reference Ford, Jaceldo-Siegl and Lee40) . The outcomes included diagnosis of anorexia or bulimia nervosa(Reference Leone, Martínez-González and Lahortiga-Ramos35), symptoms of depression(Reference Kyrozis, Psaltopoulou and Stathopoulos36), incident depression diagnosis(Reference Sánchez-Villegas, Verberne and De Irala38), development of severe depressed mood(Reference Wolfe, Ogbonna and Lim39) and positive affect(Reference Ford, Jaceldo-Siegl and Lee40). The remaining study found no association between intake and depression symptom severity(Reference Elstgeest, Visser and Penninx37). Among the cross-sectional studies, the results were less consistent. Two cross-sectional studies measuring olive oil intake reported significant reductions in symptoms of mental illness (depression and binge eating disorder)(Reference Pagliai, Sofi and Vannetti26,Reference Bertoli, Spadafranca and Bes-Rastrollo27) with higher intake, while three cross-sectional studies measuring olive oil intake reported a significant increase in symptoms of mental illness (depression and anxiety)(Reference Vučković, Radić and Gelemanović23–Reference Li, Tong and Li25). Of the seven cross-sectional studies that assessed tissue levels of oleic acid, one reported that higher levels were associated with greater plasticity among children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder(Reference Sumich, Matsudaira and Heasman34). Four of the seven cross-sectional studies measuring tissue levels of oleic acid found no assocaition(Reference Cocchi and Tonello28,Reference Kim, Jhon and Kim29,Reference Assies, Lieverse and Vreken32,Reference Kim, Schäfer and Klier33) , while two reported an association between higher levels and worse mental health: higher levels were found in criminal offenders compared with control subjects and increased levels were associated with increased diagnosis of depression(Reference Virkkunen, Horrobin and Jenkins30,Reference Assies, Lok and Bockting31) .

Table 2. Observational studies

TBSP, tablespoon; BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory II; MDD, major depressive disorder; NS, not significant; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; MADRS, Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; GAF, Global Assessment of Functioning; NEO-FFI, NEO Five-Factor Inventory; HR, hazard ratio.

Ten animal studies designed to assess the effect of olive oil met criteria for inclusion (Table 3)(Reference Kokras, Poulogiannopoulou and Sotiropoulos41–Reference Mikami, Kim and Park50). All of these studies used rodent models. Five studies measured the impact of olive oil supplementation while five assessed the impact of oleuropein supplementation. Nine of ten animal studies reported significant improvements in mental health outcomes with higher olive oil consumption(Reference Kokras, Poulogiannopoulou and Sotiropoulos41–Reference Lee, Shim and Lee47,Reference Murotomi, Umeno and Yasunaga49,Reference Mikami, Kim and Park50) . Three studies reported a decrease in anxiety-like behaviour(Reference Pitozzi, Jacomelli and Zaid42,Reference Nakajima, Fukasawa and Gotoh44,Reference Murotomi, Umeno and Yasunaga49) , two studies reported a decrease in depression-like behaviour(Reference Xu and Nie43,Reference Mikami, Kim and Park50) and three studies reported a decrease in both anxiety and depression-like behaviours(Reference Kokras, Poulogiannopoulou and Sotiropoulos41,Reference Badr, Attia and Al-Rasheed45,Reference Perveen, Hashmi and Haider46) . One study reported a decrease in cognitive impairments associated with post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)(Reference Lee, Shim and Lee47), while one study reported no improvement in anxiety-like behaviour(Reference Hryhorczuk, Décarie-Spain and Sharma48).

Table 3. Animal studies

LFD, low-fat diet.

Thirteen interventions studies using olive oil as a comparator were eligible for inclusions (Table 4)(Reference Gertsik, Poland and Bresee51–Reference Meyer, Grenyer and Crowe63). Of the thirteen studies, twelve compared olive oil supplementation to omega 3 (n-3) fatty acids(Reference Gertsik, Poland and Bresee51–Reference Pawełczyk, Grancow-Grabka and Kotlicka-Antczak57,Reference Gabbay, Babb and Klein59–Reference Meyer, Grenyer and Crowe63) and one compared olive oil supplementation to flax oil(Reference Gracious, Chirieac and Costescu58). Sample size ranged from 30 to 132. Olive oil dose ranged from 280 mg to 8 g per day and duration ranged from 35 d to 44 weeks. Populations included individuals diagnosed with major depressive disorder(Reference Gertsik, Poland and Bresee51,Reference Park, Park and Kim53,Reference Meyer, Grenyer and Crowe63) , individuals being treated for a current depressive episode(Reference Silvers, Woolley and Hamilton56), individuals with bipolar disorder(Reference Stoll, Severus and Freeman54,Reference Gracious, Chirieac and Costescu58) , renal transplant recipients(Reference Aasebø, Svensson and Jenssen52), children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder-like symptoms(Reference Stevens, Zhang and Peck55), individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia(Reference Pawełczyk, Grancow-Grabka and Kotlicka-Antczak57), adolescents with Tourette’s disorder(Reference Gabbay, Babb and Klein59), community members reporting chronic work stress(Reference Bradbury, Myers and Meyer60), pregnant women(Reference Sousa and Santos61) and healthy subjects(Reference Fontani, Corradeschi and Felici62). Primary outcomes include changes in depressive symptoms(Reference Gertsik, Poland and Bresee51,Reference Park, Park and Kim53,Reference Silvers, Woolley and Hamilton56,Reference Sousa and Santos61,Reference Meyer, Grenyer and Crowe63) , duration of remission of bipolar disorder(Reference Stoll, Severus and Freeman54), symptoms of mania and depression(Reference Gracious, Chirieac and Costescu58), quality of life(Reference Aasebø, Svensson and Jenssen52), attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptom severity(Reference Stevens, Zhang and Peck55), severity of both schizophrenic and depressive symptoms(Reference Pawełczyk, Grancow-Grabka and Kotlicka-Antczak57), tic severity(Reference Gabbay, Babb and Klein59), changes in stress(Reference Bradbury, Myers and Meyer60) and changes in overall mood(Reference Fontani, Corradeschi and Felici62). Eight studies reported significant improvement in mental health outcomes in both the olive oil supplementation group and the intervention group(Reference Park, Park and Kim53,Reference Stevens, Zhang and Peck55,Reference Silvers, Woolley and Hamilton56,Reference Gracious, Chirieac and Costescu58–Reference Sousa and Santos61,Reference Meyer, Grenyer and Crowe63) , while four studies reported significant improvements in the intervention group compared with the olive oil supplementation group(Reference Gertsik, Poland and Bresee51,Reference Stoll, Severus and Freeman54,Reference Pawełczyk, Grancow-Grabka and Kotlicka-Antczak57,Reference Fontani, Corradeschi and Felici62) , and one study reported no significant improvements in either group(Reference Aasebø, Svensson and Jenssen52). Of the eight studies reporting improvement, four reported significant improvement in severity of depression(Reference Park, Park and Kim53,Reference Silvers, Woolley and Hamilton56,Reference Sousa and Santos61,Reference Meyer, Grenyer and Crowe63) , one reported improvement in severity of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms(Reference Stevens, Zhang and Peck55), one reported significant improvement in severity of mania and depression symptoms associated with bipolar disorder(Reference Gracious, Chirieac and Costescu58), one reported significant improvement in symptoms of Tourette’s disorder(Reference Gabbay, Babb and Klein59) and one reported significant improvements in stress(Reference Bradbury, Myers and Meyer60).

Table 4. Intervention studies using olive oil as a comparator intervention

EVOO, extra virgin olive oil; ml, milliliters; g, grams; MDD, major depression disorder; HAMD, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; MCS, Mental Component Summary; SF-36, 36-Item Short Form Survey; CES-D-K, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale Korean version; CGI-S, Clinical Global Impression Scale; CGI-I, Clinical Global Impression Improvements; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; CDSS, Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia; ADHD, Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; HDRS-SF, Short Form Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; BDI II, Beck Depression Inventory II; ASQ, Abbreviated Symptom Questionnaires; DBD, Disruptive Behaviour Disorders; CES-D, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; PSS-10, Perceived Stress Scale; YMRS, Young Mania Rating Scale; CDRS-R, Child Depression Rating Scale – Revised; GAF, Global Assessment of Functioning; YGTSS, Yale Global Tic Severity Scale; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; POMS, Profile of Mood States psychometric scale; HDRS, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; CY-BOCS, Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale.

Lastly, four animal studies used olive oil as a comparator (Table 5). Three were designed to assess the anti-depressant or anti-anxiety effects of fish oil and reported greater benefit in the groups receiving fish oil(Reference Tung, Tung and Lin64–Reference Cutuli, Landolfo and Decandia66). The fourth study assessed the effects of a pesticide on animals with an olive oil control; a depressogenic effect of the pesticide was reported(Reference Chen, Zhang and Yuan67). None of the studies reported benefit on anxiety or depressive-like behaviour in the olive oil group.

Table 5. Animal studies using olive oil as a comparator intervention

Discussion

This scoping review identified human and animal studies aiming to assess the mental health impact of dietary olive oil and its constituents. All four human experimental studies designed to assess the impact of olive oil on mental health symptoms demonstrated significant improvements in mental health with olive oil consumption. Ten of thirteen human studies using olive oil as a placebo reported some degree of improvement among participants receiving the olive oil control. Nine of 10 animal studies designed to assess the impact of olive oil on mental health symptoms showed significant improvements in anxiety and/or depression-like behaviour. The observational studies yielded somewhat inconsistent associations between mental health and increased consumption of olive oil or higher oleic acid levels.

Among the observational studies, the findings were more consistent among the prospective cohort studies compared to the cross-sectional studies. Among the cohort studies, five of six studies reported a protective effect of higher intake of olive oil. These prospective studies also had larger sample sizes (range: 610–12 059, mean: 6606) compared with the cross-sectional studies (range: 20–7635, mean: 1066). The heterogenous findings in the cross-sectional studies may be due to smaller sample size, uncontrolled confounding variables, reverse causation or other sources of bias that are more common in this study design. Additionally, many of these studies assessed tissue levels of oleic acid rather than olive oil intake. Given that other foods contain oleic acid, the tissue levels might not have provided an accurate indication of olive oil intake. It is noted that four of the five observational studies that reported an association between higher intake of olive oil constituents and increased psychopathology assessed oleic acid tissue levels or intake and not olive oil. Among the human and animal studies, there was a relatively high degree of consistency in the findings, despite significant heterogeneity in the populations, and outcomes assessed. The most commonly reported benefit was a reduction in depression symptoms; however, studies also reported a reduction in symptoms of anxiety, psychosis, bipolar disorder, Tourette‘s, attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder and stress. The doses used in the studies designed to test the effects of olive oil ranged from 15 to 47 grams per day while the doses used as comparators ranged from 280 mg to 8 grams per day; these lower doses may have contributed to the smaller benefits reported. In one study of the Mediterranean diet and cardiovascular disease, the participants in the highest tertial of olive oil intake were consuming 34·6 ± 27·4 grams per day, suggesting that doses used in the olive oil studies were more aligned with the dose obtained with the Mediterranean diet(Reference Guasch-Ferré, Hu and Martínez-González68).

Although the mechanism of olive oil’s therapeutic effects is not fully understood, the benefits are suggested to be due to its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. Hydrophilic polyphenols in olive oil, namely oleuropein, demethyloleuropein and ligstroside, have been found to be protective against oxidative damage caused by redox dyshomeostasis(Reference Servili and Montedoro69,Reference Efentakis, Iliodromitis and Mikros70) . Other compounds in olive oil, specifically 3,4-dihydroxyphenylglycol and hydroxytyrosol, have been found to act as inhibitors on inflammatory pathways(Reference Fernández-Prior, Bermúdez-Oria and Millán-Linares71). Given the known role of inflammation and oxidative stress in mental illnesses pathogenesis, these mechanisms may be responsible for a beneficial effect. Furthermore, some studies have assessed the impact of olive oil on neurotransmitter metabolism. Neurochemical studies show continual olive oil consumption decreases levels of 5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid and dopamine in the brain and increases levels of homovalinic acid, a metabolite of dopamine(Reference Perveen, Hashmi and Haider46). Based on these findings, it is hypothesised that the anxiolytic effects are due to the reduction of 5-hydroxytryptamine synthesis and metabolism in the brain. Conversely, the anti-depressive effects of olive oil are hypothesised to be due to the increase of dopamine release and turnover(Reference Perveen, Hashmi and Haider46).

In this review, our search identified many studies that used olive oil as a placebo to examine the effects of other interventions, such as n-3 supplements, on mental health. Ten of 13 human studies reported statistically significant favourable mental health outcomes in both the intervention group and the placebo group. None of the four animal intervention studies that used olive oil as a placebo reported benefit in the mental health outcomes in the olive oil group. As high-level evidence has suggested an anti-depressant effect of fish oil supplements(Reference Wolters, Von Der Haar and Baalmann72), the human studies that reported non-inferiority may further add to the evidence of olive oil’s therapeutic potential; however, given that other studies have reported conflicting or uncertain results(Reference Appleton, Voyias and Sallis73), it is very challenging to draw clear conclusions from these studies. Based on these results, olive oil should be considered a poor choice of placebo in mental health research on fatty acids due to its potential therapeutic benefits; this call has been made by other researchers as well(Reference Logan74).

This scoping review has many strengths related to its thorough and explicit methodology. The credibility of this review is enhanced by the use of a comprehensive literature search, using multiple databases and search terms. Explicit eligibility criteria and duplicate screening minimised bias in the selection of studies for inclusion. Furthermore, this scoping review addresses a gap in the existing literature on the impact of olive oil consumption on mental health. The findings of this review may be used in the design of dietary intervention studies aimed at improving mental health outcomes, which may lead to public health recommendations regarding mental health support.

This scoping review has a few limitations. First, very few human experimental trials designed to assess the impact of olive oil compared to an inert comparator were eligible for inclusion in the analysis. When considering all of the human experimental and observational studies, significant methodological heterogeneity existed. The included studies had a wide array of study designs and methodologies, including different mental health outcomes and methods of assessing olive oil exposure. Populations also varied greatly, specifically in terms of participant characteristics, sample size and country of origin. Each of these studies used varying doses of olive oil for varying durations. Limited detail was provided about the quality, source, purity or composition of the olive oil used. Studies also varied in whether extra virgin olive oil or olive oil was used as an intervention. There is a need for more randomised controlled trials that assess the impact of olive oil intake compared to a control intervention that is either inert or well understood in its impact on mental health, in order to fully understand the potential of this food in a mental health promoting diet.

Conclusions

Olive oil is considered an important component of the Mediterranean Diet, a diet which has been well researched for its role in promoting mental well-being. The findings of this scoping review provide early support for a role of olive oil in improving mental health; however, more research, particularly in the form of high-quality clinical trials is needed.

Acknowledgements

Joshua Goldernberg provided feedback on study design. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Complementary & Integrative Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U24AT012549 through the RAND REACH Center. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

M. A. conceived of this project. Both authors contributed to study design, screening and data extraction. V. E. created the first draft of the manuscript. Both authors contributed to editing and approved of the final version.

The authors report no conflicts of interest.