A balanced diet that includes enough essential micronutrients (vitamins and minerals) and fibre is critical for health promotion. To ascertain if a population is meeting such nutritional needs, culture-specific recommendations and objectives are used. The Spanish Society of Community Nutrition (SENC) and the Nutrition Unit of the WHO Regional Office for Europe have developed objectives based on specific Spanish cultural habits(Reference Serra-Majem and Aranceta1). When compliance with these objectives was assessed in a Spanish region (Catalonia), adherence was incomplete in many areas(Reference Serra-Majem, Ribas-Barba, Salvador, Serra, Castell, Cabezas and Plasencia2). The cost of food is an influencing factor on diet choice. Previous studies in a province of Catalonia have shown that healthier low-energy-density diets are both more costly(Reference Schroder, Marrugat and Covas3) and associated with a healthier lifestyle(Reference Schroder, Covas, Elosua, Mora and Marrugat4). In a French population, higher cost was associated with both low energy density and a better provision of nutrients, based on the French Recommended Dietary Allowances(Reference Andrieu, Darmon and Drewnowski5, Reference Maillot, Darmon, Vieux and Drewnowski6).

The association between daily dietary energy cost and nutritional recommendations could be of interest when initiating nutritional programmes, as some recommendations may be prohibitively expensive for some portions of the population. This fact should be taken into account when implementing nutrition policies. Therefore, our objective was to assess the relationship between daily dietary energy cost and the risk of failing to meet three or more recommendations out of twenty (including micronutrients and fibre).

Experimental methods

The subjects, methods for recruitment and collection of data from the participants of the prospective cohort study Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra (Follow-up Study of the University of Navarra; SUN) have been described in detail in a previous publication(Reference Segui-Gomez, Fuente, Vazquez, Irala and Martinez-Gonzalez7). Briefly, the recruitment of this dynamic cohort began in December 1999 and, as of the time of the present analysis performed in February 2008, it included 19 057 subjects with a mean age of 38·6 (sd 12·2) years, 60 % of whom were women. We excluded those with extreme values of energy intake (<3350 or >16 748 kJ/d (<800 or >4000 kcal/d) for men, <2094 or >14 655 kJ/d (<500 or >3500 kcal/d) for women)(Reference Willett8) (n 1700) to deal with under- and over-reporters and with biologically implausible values for height and weight (n 160), and 17 197 participants remained. These participants were analysed for the association between dietary energy cost and dietary quality, as defined by compliance with daily recommended values of essential micronutrients, taking the recommended daily intakes for folate, Ca, Na from table salt, iodine and dietary fibre according to the most current data proposed by SENC(Reference Serra-Majem and Aranceta1). For the remaining micronutrients, we obtained the recommended values published by SENC in its last available reference book(9) except for vitamin E, due to specifications for sex(Reference Varela10). We conducted sensitivity analyses taking the Estimated Average Requirement when available or the Adequate Intake, as proposed by the US National Academy of Sciences, as the recommended daily intake for individuals(11).

Participants completed a semi-quantitative FFQ that has been validated previously in Spain(Reference Martín-Moreno, Boyle and Gorgojo12). Calculations of nutrient intake were done using two of the most up-to-date food composition tables for Spain(Reference Mataix13, Reference Moreiras14). Micronutrients and fibre were adjusted for total energy intake through the residual method to provide a measure of micronutrient intake uncorrelated with total energy intake, thus isolating the variation in nutrient intake due only to the nutrient composition of the diet and not from the overall food consumption. This subsequently decreases the measurement error inherent in nutritional epidemiology assessment methods(Reference Willett and Stampfer15). Micronutrients examined were: Na, Zn, iodine, Se, folic acid, P, Mg, K, Fe, Ca, vitamins B12, B6, B3, B2, B1, A, C, D and E. Fibre was also examined.

The cost of daily food consumption was derived from the Ministry of Industry, Tourism and Commerce of Spain(16). The total daily cost of food (€/d) for each subject was calculated by multiplying the mean price of each food item per gram by the quantity in grams the subject indicated that he/she consumed in an average day and summing across all food items. To define dietary energy cost (€/4187 kJ; €/1000 kcal) we divided the total food consumption cost (€/d) by the total dietary energy intake (kJ/d) and multiplied by 4187. The participants were then divided into quintiles of dietary energy cost.

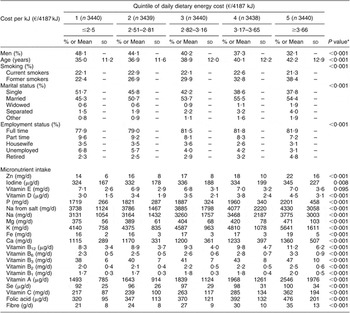

Continuous variables are expressed as means and standard deviations, and categorical variables as percentages. To assess differences between dietary energy cost quintiles we used ANOVA for continuous variables and the two-tailed Fisher exact test for categorical variables.

Since the prevalence rate ratio is more interpretable and easier to understand than the prevalence odds ratio and the odds ratio can strongly overestimate the prevalence rate ratio with frequent outcomes(Reference Barros and Hirakata17), we ran Poisson regression models with robust standard errors to estimate the age-adjusted prevalence rate ratios (PRR) and their 95 % confidence intervals for failing to meet three or more recommendations. In multivariate analyses we adjusted for smoking, marital status and employment. We considered those participants in the highest quintile of daily dietary energy cost as the reference category.

Analyses were performed with SPSS version 15·0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and STATA version 8·0 (STATA Corporation, College Station, TX, USA) statistical software packages.

Results

As participants presented higher dietary energy cost from their diet, their intake of micronutrients increased significantly (Table 1). Among all participants, the average number of recommendations which participants failed to meet was 5·2 (95 % CI 5·1, 5·2). Those micronutrients with the highest levels of failing to meet recommendations among all participants were vitamin E (79·7 %), vitamin D (72·9 %), folic acid (43·6 %), fibre (46·9 %) and Fe (52·6 %; results not shown). We found a statistically significant interaction (P < 0·001) between daily cost (quintiles) and sex. Thus, we stratified the analyses by sex. The multivariate-adjusted PRR for failing to meet three or more nutritional recommendations was highest among those participants in the lowest quintile of dietary energy cost. The PRR for the first v. the fifth quintile of daily dietary energy cost was 1·43 (95 % CI 1·38, 1·49), P for trend <0·001 among males and 1·62 (95 % CI 1·56, 1·68), P for trend <0·001 among females (Table 2). When we conducted additional analyses, choosing not meeting at least two or four recommendations as the cut-off point, the results were consistent (P for trend <0·001 for both cut-off points) but the magnitude of the estimates was higher as the cut-off increased from two to four recommendations (data not shown). In addition, when we performed continuous analyses considering as outcome the percentage of the recommendations met by the participant (nineteen micronutrients and fibre intake = 100 %) using multivariate linear regression, those male participants with the highest dietary energy cost presented an adjusted mean of 21 % (95 % CI 20, 21 %) higher percentage of meeting recommendations in comparison with those participants in the first quintile. For women the difference was 17 % (95 % CI 16, 17 %; data not shown).

Table 1 Characteristics of the cohort of 17 197 participants: the SUN (Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra) Study

Continuous variables are expressed as means and standard deviations and categorical variables as percentages.

*The P value was calculated through ANOVA for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables.

Table 2 Prevalence rate ratio (PRR) for failing to meet three or more recommendations for micronutrient intake with the fifth quintile as the reference category, the SUN (Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra) Study

*Adjusted for age, smoking, marital status and employment.

Using the North American daily micronutrient recommended intakes the results were similar especially for men. Among women the magnitude of the association was even higher (data not shown).

We ran sensitivity analyses without adjusting micronutrients for total energy intake through the residual method. The results were exactly the same for women but the magnitude of the estimates was slightly lower among men. However, the P for trend remained statistically significant (P < 0.001) and the comparison between extreme quintiles did not change substantially (first v. fifth quintile of dietary energy cost: PRR = 1·29 (95 % CI 1·24, 1·36); data not shown).

Discussion

In a large cohort of Spanish university graduates, we have found that high dietary energy cost of daily food consumption is associated with a higher likelihood of meeting the recommendations for daily intake of micronutrients and fibre. Our results are consistent with previous research in this area that has shown similar results in other populations(Reference Maillot, Darmon, Vieux and Drewnowski6), as well as evidence that there is a higher cost associated with consuming diets of higher nutritional value in regard to micronutrients and energy density(Reference Schroder, Covas, Elosua, Mora and Marrugat4, Reference Maillot, Darmon, Vieux and Drewnowski6), even though this evidence was based on smaller sample sizes. We hypothesized that these results would be consistent in our population, and the association we have found (stronger among females) is important for further research and possibilities of policy changes or changes in clinical practice in Spain.

Limitations of our study include the inability to generalize the data to the general Spanish population because of the high educational level of the participants. While these participants may have a higher income than the less educated Spanish population to spend on food, the results are reasonably free of confounding by socio-economic status (SES) because the participants we examined all had a fairly similar SES. Although similar educational level does not guarantee similar income, educational level has proved to be influential in the evaluation of SES. Analyses that have taken account of education, occupation, income and employment status have shown that education is the strongest determinant of socio-economic differences in food habits(Reference Roos, Prättälä, Lahelma, Kleemola and Pietinen18) (i.e. restriction was used to control for SES as a confounding factor). Moreover, the very low percentage of participants meeting the recommendations that we observed was found among a relatively more affluent stratum of the population, and it is likely that the problem might in any case be worse among less well-off sectors.

An additional limitation is that our exposure variable was based on answers to FFQ, which present some degree of measurement error inherent in nutritional epidemiology. This withstanding, it is unlikely that the magnitude of the prevalence rate ratio that we have found here could be explained by the potential measurement errors, which are more likely to be non-differential.

The present results contribute to the importance of considering cost when initiating nutritional programmes, as some recommendations may be prohibitively expensive for some portions of the population. Clinicians also should consider the affordability of expensive food items on the part of their patients when counselling them on diet changes for micronutrient deficiencies, as it is possible that those who are not meeting recommendations may not have the economic resources to do so.

Acknowledgements

The SUN Study received funding from the Spanish Ministry of Health (grants PI030678, PI040233, PI070240, PI081943, RD06/0045 and G03/140), the Navarra Regional Government (grants PI41/2005 and PI36/2008) and the University of Navarra. C.N.L. was supported by a Paul Dudley White Travelling Fellowship, Harvard Medical School. The authors declare no conflict of interests. The authors’ contributions were as follows. Study concept and design: C.N.L., M.A.M.-G. and M.B.-R.; acquisition of data: M.A.M.-G., C.F. and M.B.-R.; analysis and interpretation of the data: M.B.-R. and M.A.M.-G.; drafting of the manuscript: C.N.L. and M.B.-R.; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: C.N.L., M.B.-R., A.A., A.S.-V., C.F. and M.A.M.-G.; obtained funding: M.A.M.-G., A.S.-V. and M.B.-R. We thank all members of the SUN Study Group for administrative, technical and material support. We thank participants of the SUN Study for continued cooperation and participation.