In recent years, there has been a shift away from solely targeting individuals to change their eating behaviours to an approach that addresses wider, population-level factors and involves other environmental components and stakeholders( Reference Hill, Wyatt and Reed 1 ). Foodscapes( Reference Mikkelsen 2 ) and food environments contribute to the so-called ‘obesogenic environment’( Reference Hill, Wyatt and Reed 1 , Reference Hill and Peters 3 ) and influence food choices. Epidemiological data suggest that numerous small changes towards a healthier behaviour such as improving diet quality have the potential to have a positive impact on reducing mortality risk( Reference Bamia, Trichopoulos and Ferrari 4 ). Most healthy eating interventions in Europe have been successful in providing consumers with information to enable them to make better-informed food choices( Reference Wills and Grunert 5 ). Although they have been successful in creating awareness among consumers, there has only been modest success in terms of actual lifestyle changes and measurable health indicators in the sample populations, such as weight reduction( Reference Perez-Cueto, Aschemann-Witzel and Shankar 6 ). Individualised behaviour change is ineffective unless it becomes habit forming, which requires support and reinforcement through structural or environmental change so that the new behaviour is sustained. Although behavioural economics have impacted on some policy interventions, the case for food-related interventions remains under development, constituting a promising area that could potentially achieve high social benefits( Reference Johnson, Shu and Benedict 7 , Reference List and Samek 8 ).

Therefore, innovative intervention strategies that are able to effectively improve food behaviours, dietary intake and impact on health status need to be investigated and implemented. The majority of interventions have an underlying assumption that people make conscious and reasoned food choices, most of the time( Reference Riebl, Estabrooks and Dunsmore 9 ). This paradigm has been questioned following the limited impact of information-based campaigns in achieving behaviour change, and the subsequent rise in the prevalence of obesity and other chronic diseases( Reference Brambila-Macias, Shankar and Capacci 10 ). Furthermore, current paradigms place the burden and responsibility for all food choices on the individual, with the justification that everyone is free to make healthy choices once informed( Reference Perez-Cueto, Aschemann-Witzel and Shankar 6 , Reference Capacci, Mazzocchi and Shankar 11 ).

Dietary habits and food choices are the result of decisions and actions that are based on routines that require very little active decision making as well as reflective, elaborate decision making where choice options are carefully considered. Choice architecture, inspired by behavioural economics, describes the way in which decisions are influenced based on how choices are presented within meal environments( Reference Hansen and Jespersen 12 ). The meal environment has been defined as the room, the people, the food, the atmosphere and the management system, particularly when eating out of home. This suggests that the meal environment can be modified to be more or less conducive to support the required behaviour and as such may lead to weight changes, either through promotion of healthier choices or through decreased intake( Reference Hansen and Jespersen 12 – Reference Thaler and Sunstein 15 ).

Choice architecture is often used interchangeably with other terms such as nudging, libertarian paternalism and behavioural economics. Choice architecture is a subset of non-regulatory behavioural interventions. Choice architecture can include one or more of the following: provision of information (e.g. to activate a rational choice), changes in the physical environment (e.g. light, décor, placement, etc.), changes in the default policy (e.g. pre-weighed salad portions v. free serving of a salad bowl) and use of social norms and salience (e.g. comparison with average consumers)( 16 ). Nudging has been defined as any aspect of the choice architecture that alters people’s behaviour in a predictable way without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic incentives( Reference Thaler and Sunstein 15 ). Within the public health nutrition area, this could mean altering the food environment, such as product placement or labelling or even encouraging consumers to sit together for their meal (social facilitation). Furthermore, nudging interventions consist of provision of information, changes to physical environment, changes to the default policy and the use of social norms and salience( 16 ).

Previous studies have shown that nudging practices are promising measures that can be used to support the promotion of healthy eating. An example of nudging is that by changing the size of dishware, portion sizes may be reduced leading to unconscious changes in actual food intake( Reference Skov, Lourenco and Hansen 17 ) and meal composition( Reference Libotte, Siegrist and Bucher 18 ). Similarly, food positioning is thought to influence food choice. Studies have shown that people eat more unhealthy food such as chocolate if it is located more prominently( Reference Wansink, Painter and Lee 19 ). However, it is less clear whether minor changes in food position or item placement, which are not accompanied by changes in effort, also promote healthier food choices( Reference Rozin, Scott and Dingley 13 , Reference Bar-Hillel and Dayan 20 ).

Existing systematic reviews that have investigated the effectiveness of choice architecture interventions have mainly focused on the effectiveness of labelling and prompting( Reference Sinclair, Cooper and Mansfield 21 , Reference Campos, Doxey and Hammond 22 ). However, these types of interventions are more closely related to the traditional behavioural interventions of information giving( Reference Hollands, Shemilt and Marteau 23 ). To date, there is no systematic review that has assessed the influence of food placement within microenvironments on product choice and on food intake( Reference Hollands, Shemilt and Marteau 23 ). This information is relevant for the support of public health interventions and relevant for operations in the food service sector.

The aims of this systematic review were to evaluate published articles that have investigated the effect of positional changes within microenvironments on food choice by healthy weight and overweight individuals across all age groups and to derive recommendations for future research in the area.

For the purpose of this review, we have defined a nudging intervention as any intervention that involves altering the non-economic properties or placement of objects or stimuli within micro-environments with the intention of changing health-related behaviour. Such interventions are implemented within the same micro-environment in which the target behaviour is performed and require minimal conscious engagement. In principle, these interventions can influence the behaviour of many people simultaneously, and they are not targeted or tailored to specific individuals (adapted from Hollands et al.( Reference Hollands, Shemilt and Marteau 23 )). The present review focuses on positional changes that affect immediate food consumption or choice decisions of individuals (e.g. eating out of home in a food service outlet), rather than the consumption pattern of a family or a household over time, as it would be the case in ‘assortment structure’ experiments within supermarket settings.

Methods

Details of the protocol for this systematic review were registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) and can be accessed at http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42015016277

Criteria for study inclusion

The PICOS (Problem, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Setting) approach( Reference Liberati, Altman and Tetzlaff 24 ) was used to frame the research question. We defined ‘food choice’ as all outcome measures that assessed food selection or probability of food choice, including product sales and food consumption (in grams or energy intake). Positional changes were defined as all manipulations of food order or variations in the distance of food placement relative to consumers within microenvironments. Microenvironments were defined as the immediate surroundings of the individuals, such as within the home, workplace or cafeterias( Reference Kahn and Wansink 25 ).

The types of studies to be included were randomised-controlled trials/experiments, pre–post experimental studies, quasi experiments and naturalistic observations where at least one research aim was to assess the influence of food positioning within a microenvironment on food choice (selection) or sales (grams, number) and intake (grams, energy).

Studies where multiple variables were manipulated simultaneously along with the food position were not included. For example, studies where foods were added or removed from the selection or where portion sizes of healthy or unhealthy offers were altered along with a positional change were excluded. Study participants included only healthy, normal-weight or overweight/obese individuals. There was no age restriction with studies on both children and adults included. The search included full-text articles that were published in peer-reviewed journals in the English language.

Literature search

A systematic search was conducted using electronic databases (Medline, Pre-Medline, Embase, CINAHL, Scopus, The Cochrane Library and PsycINFO) until February 2015. No limit was placed on publication date. The search term list included the following items: choice architecture OR accessib*OR nudg* OR position* OR (serving AND (direction OR distance)) OR proximity OR distance AND food OR diet OR food choice OR energy intake OR caloric restriction OR fruits OR vegetables OR health* OR food choice. Reference lists of included articles and key reviews in the area were also manually searched for additional articles.

Review procedure

Two independent reviewers (T. B. and N. D. V./D. V. d. B.) screened the titles and abstracts of all search results. Full texts of all papers that appeared to potentially meet the inclusion criteria were retrieved. The retrieved full texts were assessed by two independent reviewers (T. B. and N. D. V.) to determine inclusion. In case of disagreement, a third independent reviewer made the final decision (M. E. R.).

Data extraction and synthesis

Quantitative data on study participants (age, sex, weight status), the design (type of study, setting, manipulated variables) and the outcomes (finding, main effect, conclusions) from the included articles were extracted by T. B. and checked by M. E. R. To distinguish between the magnitude of the change in effort that was involved in the intervention, we differentiated between minor changes (mere order change or very small distance change within reach), medium (change of position to food that required only a small effort, e.g. standing up, bending down) or major positional changes (manipulations that involved a major increase/reduction in effort, e.g. walking across a room).

Quality assessment of included studies

The quality of the included studies was assessed by two independent reviewers (T. A. M. and H. T.) using the review evidence analysis manual published by the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics( 26 ). The quality scores can be found in the online Supplementary Table S1.

Results

The database search identified 2540 unique entries, which were combined with another thirty-six articles of interest that were identified by screening reference lists. A total of sixty-two full-text articles were retrieved and assessed against the inclusion criteria. In total, fifteen articles, comprising eighteen studies, met the inclusion criteria and the data from these were extracted and evaluated in this review (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Flow of information through the different phases of the review.

The majority (n 10) of studies were conducted in the USA; seven were conducted in Europe, of which four were conducted in the Netherlands. In one study, the country was not reported( Reference Levitz 27 ). There was only one study on children( Reference Musher-Eizenman, Young and Laurene 28 ). Moreover, ten studies were conducted with university students or staff, and for five studies the subjects were customers of hospital cafeterias. Only one study was conducted in an Army research centre( Reference Engell, Kramer and Malafi 29 ) and one was conducted with attendees of a health conference( Reference Wansink and Hanks 30 ).

The foods involved in the studies varied and included single healthy or unhealthy items (water, fruit and vegetable, cereal bars, chocolate candy or crackers) to more complex selections within canteen buffets with between eight and eleven products repositioned.

Among all, seven studies reported participants’ weight status; however, only two considered it in the analysis( Reference Levitz 27 , Reference Meyers, Stunkard and Coll 31 ). Levitz( Reference Levitz 27 ) reported that a change in dessert order affected normal-weight and overweight people differently. In particular, the author found that obese adults selected a greater amount of low-energy dessert if it was made more salient. No changes were observed if the high-energy desserts were made more salient( Reference Levitz 27 ).

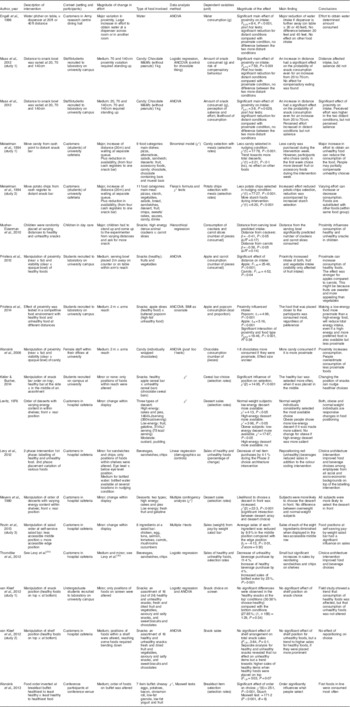

The characteristics of the included studies are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1 Characteristics of included studies (n 18) assessing the effect of positional changes in the microenvironment on food choiceFootnote *

* ± indicates the standard deviation.

Of the eighteen studies that were included, only one received a positive quality rating( Reference van Kleef, Otten and van Trijp 32 ), with fourteen studies being assessed as neutral and three as negative, because study procedures were not described in detail and several validity questions could not be answered clearly (online Supplementary Table S1).

Of the eighteen studies, nine investigated the effect of distance/proximity changes on food choice, such as placing unhealthy foods further from the consumer. The other half assessed whether changes in product order, such as, for example, the food sequence on a buffet, could have a beneficial influence on food selection.

In summary, sixteen of the eighteen studies concluded that positional changes had a positive influence on food choice. The only two studies that did not find an effect manipulated the product order of snacks on a computer screen (Van Kleef Study 1), as well as within a shelf at a checkout counter in a cafeteria (Van Kleef Study 2). However, in the field study, they found a trend towards sales of healthy food being positively affected( Reference van Kleef, Otten and van Trijp 32 ).

It was not possible to quantify and directly compare the effect sizes of the included studies, as the study designs were too variable. Most of the studies were randomised-controlled experiments, and only one study used correlation analysis to study the relationship between distance and snack selection( Reference Musher-Eizenman, Young and Laurene 28 ). This study found that the distance from the serving bowl significantly predicted the number of crackers and carrot slices consumed by children( Reference Musher-Eizenman, Young and Laurene 28 ).

Between-subject experiments were the most common study design, whereas within-subject, repeated-measures designs were rarely used. Only one study used a longitudinal design( Reference Levy, Riis and Sonnenberg 33 ), which was a follow-up assessment of the intervention described by Thorndike et al.( Reference Thorndike, Sonnenberg and Riis 34 ) and was based on the same choice architecture intervention. Both of these studies were retained in the review because they had assessed different outcome measures and were complementary.

Most studies assessed food selection or choice probability using χ 2 tests, whereas only a few studies objectively measured actual food intake in terms of food weight (g) or energy (kJ/kcal) content. The intervention description and findings of the included studies are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2 Intervention description and findings of the included studies (n 18)

Discussion

Out of eighteen studies where food position or order was manipulated, sixteen showed a positive effect on food choice, meaning that the participants were nudged towards a more healthy food choice. In the two experiments( Reference van Kleef, Otten and van Trijp 32 ) where positional changes had no impact on food choice, the degree of manipulation was only a minor change in position, with all the foods remaining within reach. This indicates that the strength of the effect appears to depend on the type of positional manipulation (order v. distance), as well as the magnitude of the change, or how far away foods are placed.

Only one study assessed compensatory food choices( Reference Meiselman, Hedderley and Staddon 35 ), showing that changes in position resulted in compensatory choices within same food categories. Further, movement of potato chips to a more distant location, and hence a reduction in chips selection, was accompanied by an increase in starch selection choices among the foods that still remained proximal( Reference Meiselman, Hedderley and Staddon 35 ). For portion size changes, there is some evidence from previous research that reducing offered portion sizes does not result in immediate compensation( Reference Schwarz, Riis and Eibel 36 ). However, in that particular study, the intervention was conscious, and consumers’ self-control was activated by having servers ask customers in a fast food restaurant whether they wanted to downsize portions. Other studies, in which the overall energy of a meal bundle for children was reduced, without the participants being aware, found that the overall energy intake was significantly reduced( Reference Wansink and Hanks 37 ). More research on compensatory behaviours is required to implement effective interventions in practice.

The overall quality of the included studies was neutral. Only a few papers described the procedures sufficiently well to allow a clear evaluation of all validity questions. In particular, the questions that related to subject selection, recruitment procedures and comparison of study groups were unclear or not applicable. Studies were classified as unclear or not being free from bias because of the use of cash incentives or course credit being offered to participants. This may be an artifact of the naturalistic setting of the studies, such as universities and workplace canteens.

There is a lack of research investigating long-term outcomes of positional interventions, and it is not clear whether changes in product order or distance would have sustained effects. Specifically, it is unclear whether a potentially positive effect of a position change, such as placing healthy foods in obvious positions and very close to cafeteria check-out lines, would potentially diminish over time and that customers would return to selecting a favoured unhealthy snack. To investigate this, more studies have to be conducted that evaluate this. Changes in choice need to be assessed at different time points, ideally over several weeks and months – for example, using data from a customer loyalty card scheme to determine sustainability of the intervention.

Furthermore, only one study( Reference Maas, de Ridder and de Vet 38 ) assessed the effect of potential covariates such as food preferences, restrained or disinhibited eating styles or health consciousness on the outcomes of position choice architecture interventions. It therefore remains unclear which individuals are susceptible to nudges. Further insight on these covariates, as well as potential influences of habit strength, is required to design effective interventions.

A reason for these data not being reported may be that it is important to ensure participants are not aware of the nudging intervention, and this is likely to be the reason most field studies did not collect this information from participants. A method that could be used to address this limitation in future research would be to implement interventions within settings where customer loyalty cards are used to collect additional data on participants’ actual purchases. For this purpose, collaborations with industry or supermarket chains could be effective. This would also have the advantage that potential product price and positioning interactions could be assessed.

Previous literature suggests that nudges could be inexpensive approaches to positively impact behaviours( Reference Thaler and Sunstein 15 ). In the studies included in this review, however, there were no calculations on potential costs and benefits. Factual data on previously hypothesised benefits are required to make effective recommendations for policymakers.

Only two studies differentiated between healthy and overweight consumers and whether positional interventions were different based on body weight( Reference Levitz 27 , Reference Meyers, Stunkard and Coll 31 ). They both concluded that the positional nudges were effective irrespective of weight status. Further, one study assessed socio-economic status and reported that it had no influence on whether positional interventions were effective( Reference Levy, Riis and Sonnenberg 33 ). These findings concur with previous literature, which suggest that nudging effects work via subconscious mechanisms, and therefore have equal impact regardless of weight and socio-economic status( Reference Marteau, Ogilvie and Roland 39 ).

Food position can be manipulated by changing the order of food products or by changing the distance between the food and the consumer. Both of these nudges operate in different ways. The mediating factor for the effect of distance on choice is thought to be effort, whereas for change in order it is reported to be salience( Reference Maas, de Ridder and de Vet 38 ). Changes in order normally constitute only a minor change in effort, whereas changes in distance affect the effort required in order to obtain a food at various levels. However, more research is needed to evaluate these two aspects in detail. Future research should also clearly distinguish between studies that examine nudging in terms of food order v. food proximity or distance.

To date, very little is known about why positional nudges could be effective, and, in particular, it remains unclear how effects are moderated. The dual-process model( Reference Strack and Deutsch 40 ) states that human behaviour largely results as a function of two interacting systems: the reflective system, which generates decisions based on knowledge about facts and values, and the impulsive system, which elicits behaviour through affective responses. The first system requires cognitive capacity, whereas the second system requires no cognitive effort and is driven by feelings and immediate behaviours in response to the environment. Nudging is thought to operate mainly through the second, automatic system and affects all individuals equally. However, it remains to be elucidated whether and how factors such as health consciousness, habits or strong preferences for specific products interact with the effects. The research of Levy et al.( Reference Levy, Riis and Sonnenberg 33 ) suggests that once the social gradient effects are taken into consideration, there is still an effect towards the desired outcome in terms of food choices. This indicates that these interventions could be powerful and that cheap nudging interventions could potentially yield more than other elaborate expensive campaigns do. However, further research is required to explore this in detail.

It was not possible to conduct a meta-analysis of effect sizes as a wide range of outcome measures were reported across studies. Although the evidence that food position influences food choice was consistent across studies, it was not possible to evaluate the impact and effect size of these types of choice architecture interventions on actual food consumption and subsequent health outcomes. As has been advocated previously( Reference Perez-Cueto, Aschemann-Witzel and Shankar 6 ), harmonised indicators are required that would allow comparability between experiments or interventions. We therefore strongly recommend the use of energy (kJ/kcal) or weight (g) as outcome measures of changes in food selection and/or intake in future studies.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first systematic review that has assessed the influence of position interventions (proximity and order) on food choice. In addition to the terms ‘nudging’ and ‘choice architecture’, we used search terms such as ‘distance’ and ‘position’. This strategy located many articles that were beyond the topic of interest such as access to fast food outlets, but ensured that older literature published before the terms ‘choice architecture’ and ‘nudging’ became popular were included.

For the purpose of this review, we defined nudging as any intervention that involved altering the non-economic properties or placement of objects or stimuli within microenvironments, with the intention of changing health-related behaviour (adapted from Hollands et al.( Reference Hollands, Shemilt and Marteau 23 )). We acknowledge that varying definitions of this term exist and that a disparate definition of the term might have led to the inclusion of different studies, and hence influence the conclusions drawn.

Literature investigating the effect of the assortment structure on buying behaviour within supermarkets was not identified with the present search strategy. The authors are aware that supermarket-related shopping behaviour has been extensively described in the marketing literature, and that it is one of the venues where behavioural interventions may have a socially relevant outcome( Reference Johnson, Shu and Benedict 7 , Reference Ducrot, Julia and Méjean 41 ). This aspect was beyond the scope of the present study, which focused mainly on out-of-home meal service situations such as cafeterias or canteens. Factors affecting selection at the time of consumption and the time of purchase may differ in this situation.

In addition, it is relevant to note that there could be differences between nudges that aim to increase or decrease consumption, as well as between nudges that promote the choice of healthy foods v. nudges that discourage the consumption of unhealthy foods. As an example, it might be easier to promote the consumption of more (healthy) food, compared with discouraging the consumption of unhealthy (or preferred) food by positional changes. Studies in which the positions of unhealthy and healthy foods are simply switched are particularly problematic, as they lack a neutral control group, which would enable researchers to disentangle whether there was a potential bias in effectiveness of nudging depending on the food. In the present literature, studies that strategically investigated the efficacy of the positional intervention depending on food type are missing.

This review did not specifically consider any grey literature. Given the heterogeneity and the limited number of studies retrieved via the search strategy, it is plausible that a positive publication bias exists, although this was not assessed by the authors. It is interesting to note that the paternalistic nature of the concept of nudging has been discussed. In particular, it can be argued that a positional change that results in high effort to obtain an unhealthier food may be seen as a reduction in freedom of choice( Reference Blumenthal-Barby and Burroughs 42 – Reference Potts, Verheijde and Rady 45 ). However, owing to the ethical nature of this discussion, it is beyond the scope of this review.

The synthesis of the study findings was undertaken in a narrative format as data aggregation was limited by the heterogeneity of the research in this field. Nevertheless, the current review identified gaps in the existing literature and where further research is needed.

Recommendations for laboratory studies

Although laboratory settings are limited, well-planned experiments could give insight into the strength of positional effects, and therefore help estimate the cost-effectiveness of choice architecture interventions in practice, particularly if repeated measures are applied. Laboratory settings allow the follow-up of the same individuals for data collection. Quantifiable outcome measures such as change in energy (kJ/kcal) or weight (g) of food selection or consumption should be used. Strong experimental evidence including estimations of the potential health benefits secondary to a reduction in energy intake or consumer weight loss over time is needed to inform policymakers in terms of implementing choice architecture interventions in public health settings.

Recommendations for field experiments

Although previous research suggested that substitution might occur within the same product category following a choice architecture intervention( Reference Meiselman, Hedderley and Staddon 35 ), a trial in the Belgian city of Ghent showed that meal choices were not compensated for later in the day( Reference Hoefkens, Lachat and Kolsteren 46 ). Hence, future research should address the issue of compensation at the design stage and consider that compensatory behaviours could occur after a nudge intervention.

As for laboratory settings, we also strongly recommend the use of energy or grams of food selected/consumed as an objective outcome measure, to estimate effect sizes and potential health benefits.

Furthermore, insight into factors (e.g. preferences, habit strengths, health consciousness) that potentially influence the effectiveness of positional interventions could be gained by collecting more information on customers in cafeteria-style settings – for example, via a loyalty card scheme. This would further allow exploration of the sustainability (decay of effect over time or potential compensatory choices) over time in these settings.

Reporting recommendations

The eighteen studies included in this review did not consistently describe the choice architecture intervention that was being assessed – for example, whether ‘the nudge’ was a change in distance or in product positioning. On the other hand, the inclusion of distance in combination with food resulted in a large number of search results that were not relevant for the purpose of this study.

We suggest that standardised keywords and vocabulary could assist this field of research. Researchers should carefully consider the wording for their reports and could adopt the terminologies suggested by Hollands et al.( Reference Hollands, Shemilt and Marteau 23 ) to classify choice architecture interventions more clearly.

Advice for practice (policymakers, food retailers)

Choice architecture recommendations could support existing dietary guidelines, and thus potentially contribute to the adherence and compliance. Although more research is required to quantify the magnitude of positional influences on health outcomes, it is evident that choice architecture is important and that food retailers influence consumption by organising and displaying their products. Therefore, persons in charge of food organisation or food outlet design (e.g. workplaces) need to be aware of their responsibility to organise ‘foodscapes’ in an optimal way – for example, to stimulate consumption of healthy foods and to reduce the consumption of unhealthy foods that then could support healthy workplace initiatives. In practical terms, this means that low-energy, nutrient-dense products such as fruits and vegetables should be placed in easily accessible and prominent positions. This is particularly applicable in large self-serving setting such a school or work canteens or the canteens of residences for the elderly.

Policymakers could integrate choice architecture nudging measures to augment their existing policy documents as an important measure to enhance the effectiveness of healthy eating policies and procedures. In particular, this review provides evidence for policymakers, and specifically supports the use of positional changes as an effective manner to alter food choice in a desirable way.

Furthermore, the results of this review could be used for developing official recommendations regarding the implementation of choice architectural nudge interventions and to harmonise the indicators for evaluation of the effect. A good practice example would be to place salad at the beginning of the buffet in school canteens in countries where meals are provided at school.

Conclusions

Although the evidence that food position influences food choice is consistent, it is difficult to quantify the magnitude of impact on food choice and intake and the effect size of these choice architecture interventions on actual food consumption and subsequent health outcomes. Use of harmonised terminology and indicators would allow comparability between experiments or interventions and assist in moving this field forward.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Debbie both for assistance with developing the search strategy and the database searches.

T. B. received a fellowship from the Swiss National Science Foundation (P2EZP1_159086) and the Swiss Foundation for Nutrition Research (SFEFS) to work on this project. C. C. is supported by an NHMRC Senior Research fellowship. F. J. A. P. C. is supported by IAPP-Marie Curie FP7/EU grant (agreement no. 612326 VeggiEAT). The funding sources had no influence on the design of the study.

T. B., N. D. V. and D. V. d. B. screened the abstracts; T. B. and M. E. R. extracted the results; and T. A. M. and H. T. performed the quality assessment. T. B. and F. J. A. P. C. jointly wrote the manuscript with critical input from C. C., H. T., M. E. R. and T. A. M.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material/s referred to in this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1017/S0007114516001653