Introduction

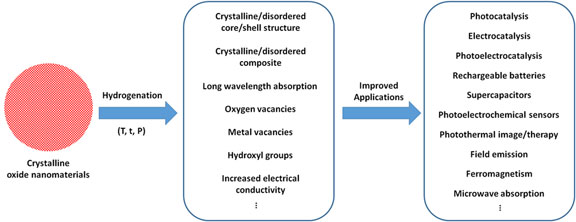

It is well known that the performance of nanomaterials in various applications depends largely on their properties, which are controlled by their chemical compositions, physical sizes, dimensions, structures, and morphologies.[ Reference Murray, Kagan and Bawendi 1 – Reference Alivisatos 3 ] The past decades have witnessed the blooming fruits of the efforts in the property manipulations with nanoscale size and morphology tuning.[ Reference Murray, Kagan and Bawendi 1 – Reference Alivisatos 3 ] Representative examples are the large flexibilities of the optical absorption and emission properties of quantum dots or plasmonic particles by changing their sizes and morphologies, benefited from the changes of the electronic structure or plasmonic resonance upon those changes in their physical properties.[ Reference Murray, Kagan and Bawendi 1 – Reference Alivisatos 3 ] Another example is the large variation of the chemical and catalytic activities with the change of the size of the nanomaterials, which reversely increases the specific surface area and the portion of atoms exposed on the surface with dangling bonds, along with the change of exposed surface facets.[ Reference Murray, Kagan and Bawendi 1 – Reference Alivisatos 3 ] The findings in these two phenomena have opened new applications or enhanced performances of nanomaterials in catalysis, electronics, biosensing, imaging, etc. The recent discovery of black titanium dioxide (TiO2) suggests that the optical, electronic, and catalytic activities of nanomaterials can be largely modified by treating them in hydrogen environment at elevated temperature, or namely by a hydrogenation process.[ Reference Chen, Liu, Yu and Mao 4 ] For example, the color of TiO2 nanoparticles changes dramatically from white to black after hydrogenation, the electronic band structure is largely altered, and the photocatalytic activity is dramatically enhanced for both solar hydrogen generation from water and photocatalytic pollution removal.[ Reference Chen, Liu, Yu and Mao 4 ] The report of those large changes in the properties of TiO2 nanoparticles has spurred a wide interests across various fields using hydrogenation as a new tool to modify the properties of various oxide nanomaterials for different applications as shown in Fig. 1.[ Reference Cronemeyer and Gilleo 5 – Reference Xia and Chen 20 ] The structural, chemical, electronic and optical properties of oxide nanomaterials can be largely modified by hydrogenation treatment. For example, after hydrogenation, crystalline/disordered core/shell nanoparticles can be created easily otherwise with much difficulty, long-wavelength absorption can be introduced, structural and chemical defects are introduced, and enhanced electrical conductivity can be obtained. Those property changes can lead to large performance improvements for their applications in photocatalysis, electrocatalysis, photoelectrocatalysis, rechargeable batteries, and supercapacitors, and trigger new applications such as photothermal image/therapy, field emission, ferromagnetism, and microwave absorption. Future studies may further reveal more interesting properties and applications of oxide nanomaterials after hydrogenation treatment. In this short perspective, we present some representative examples to demonstrate the progress in this area. We believe such a summary would provide some helpful information and inspire new thoughts and ideas to further advance the progress in related research areas.

Figure 1. A brief summary of the characteristics of oxide nanomaterials after hydrogenation and the related applications.

Hydrogenation process

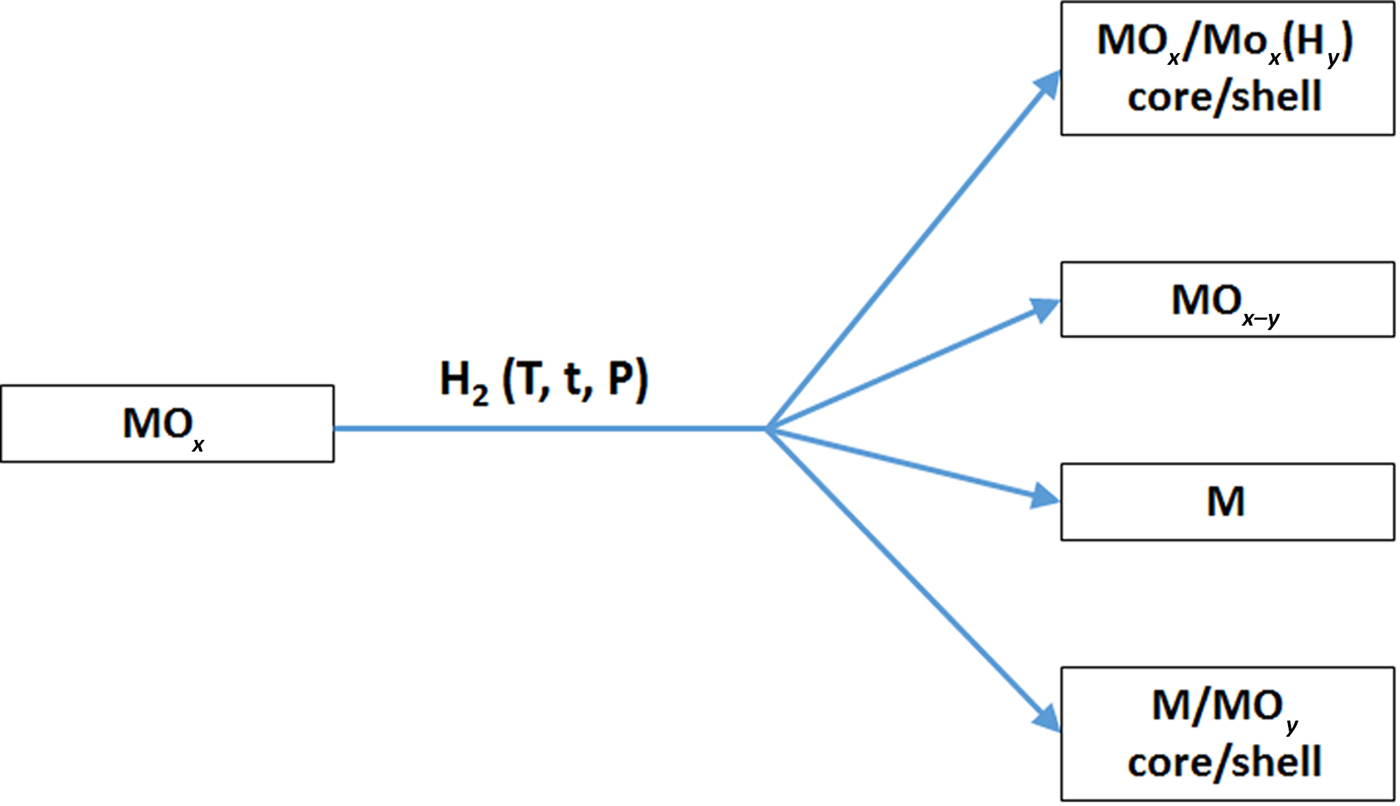

First, we want to define the term “hydrogenation” to remove some possible confusion. The hydrogenation process here refers to the treatment of materials under hydrogen-containing environment or hydrogen plasma for certain period of time at some temperatures. Hydrogenation—to treat with hydrogen—is commonly employed in organic industries and laboratories to reduce or saturate organic compounds where hydrogenation typically constitutes the addition of pairs of hydrogen atoms to a molecule. In the hydrogenation process here, the nanomaterials may or may not be reduced, depending on the hydrogenation conditions. Possible results of hydrogenation of inorganic nanomaterials can produce the following typical scenarios, as shown in Fig. 2. (A), hydrogenation can only induce structural alteration, e.g. from crystalline phase to disordered phase, but without measurable chemical valence state changes, forming crystalline/disordered core/shell nanostructures. (B), hydrogenation induces partial chemical reduction to introduce lower valence state or oxygen vacancies. (C), hydrogenation causes deep chemical reduction to form completely reduced metallic phase. (D), hydrogenation makes complete chemical reduction to form metallic phase, but the followed exposure to air in ambient environment induces oxidation on the surface to form disordered layer, resulting crystalline/disordered metal/oxide core/shell nanostructures. The formation of the above nanostructures depends on the nature of the nanomaterial and the hydrogenation conditions, such as the hydrogenation temperature, time, hydrogen pressure, and the composition of the atmosphere containing the hydrogen gas. Thus, the control of the hydrogenation process after common nanomaterials' synthesis or fabrication steps can further increase the choices of the nanomaterials' chemical compositions, structures and phases to induce desirable properties for various applications. In the following sections, we will present some representative examples to show how the hydrogenation can alter the structural, chemical, electronic and optical properties of some oxide nanomaterials along with their related performance in various applications.

Figure 2. Illustration of some possible scenarios of the chemical composition changes for oxide materials after hydrogenation treatments.

Hydrogenated TiO2 nanomaterials

Hydrogenated TiO2 single crystals were reported in 1951 with long-wavelength absorption[ Reference Cronemeyer and Gilleo 5 ] and in 1958 with increased electrical conductivity[ Reference Cronemeyer 6 ] due to the existence of oxygen vacancies[ Reference Cronemeyer 6 , Reference Sekiya, Yagisawa, Kamiya, Das Mulmi, Kurita, Murakami and Kodaira 7 ] or mostly Ti interstitial defects.[ Reference Hasiguti and Yagi 8 , Reference Yagi, Hasiguti and Aono 9 ] Pale blue or dark blue TiO2 was obtained.[ Reference Sekiya, Yagisawa, Kamiya, Das Mulmi, Kurita, Murakami and Kodaira 7 ] While molecular hydrogen did not interact strongly with TiO2 surfaces,[ Reference Henrich and Kurtz 10 ] high doses of H2 induced additional emission peaks in the valence band region even at room temperature,[ Reference Lo, Chung and Somorjai 11 ] and at room temperature atomic hydrogen stuck to TiO2 (110) surfaces.[ Reference Pan, Maschhoff, Diebold and Madey 12 ] Hydrogenation on TiO2 surface in a H2 atmosphere of a very low pressure could induce chemical reduction,[ Reference Lazarus and Sham 13 , Reference Zhong, Vohs and Bonnell 14 ] and increased the photoactivity.[ Reference Heller, Degani, Johnson and Gallagher 15 , Reference Liu, Ma, Li, Li, Wu and Bao 16 ] However, a large interest on the hydrogeantion of TiO2 nanomaterials did not appear until our report of the striking color change into black color and the related dramatic electronic and photocatalytic property changes.[ Reference Lu, Wang, Zhai, Yu, Gan, Tong and Li 17 – Reference Zheng, Huang, Lu, Wang, Qin, Zhang, Dai and Whangbo 25 ] When anatase TiO2 nanocrystals go through hydrogenation under high-pressure H2 environment at 200 °C for a few days, a crystalline/disordered core/shell nanoparticle is formed without detectable species of reduced Ti3+ ions using both surface and bulk chemical measurement techniques (such as x-ray photoelectron spectrosocpy and x-ray absorption spectroscopy), surprising contradictory to our common sense that reduced form of Ti4+ ions would form under such condition.[ Reference Chen, Liu, Yu and Mao 4 , Reference Chen, Liu, Liu, Marcus, Wang, Oyler, Grass, Mao, Glans, Yu, Guo and Mao 18 – Reference Xia and Chen 20 ] The hydrogen employed is found to play an important role in stabilizing the disordered layer, which makes a large contribution to the long-wavelength absorption and the enhanced charge separation and photocatalytic activity.[ Reference Chen, Liu, Yu and Mao 4 , Reference Chen, Liu, Liu, Marcus, Wang, Oyler, Grass, Mao, Glans, Yu, Guo and Mao 18 , Reference Liu, Yu, Chen, Mao and Shen 19 ] Figure 3 shows a schematic illustration of the lattice and electronic structures, representative pictures, high-resultion transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) images, ultraviolet-visible (UV-vis) and valence band x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (VB-XPS) spectra of hydrogenated black and normal white TiO2 nanoparticles.[ Reference Chen, Liu, Yu and Mao 4 ] Clearly, apparent changes can be seen after hydrogenation. Enhanced photocatalytic activities in producing hydrogen from water and in removing organic pollutants (methylene blue and phenol) are achieved with the hydrogenated crystalline/disordered core/shell nanoparticles.[ Reference Chen, Liu, Yu and Mao 4 ]

Figure 3. (a) A schematic illustration of the lattice and electronic structures of hydrogenated black TiO2, (b) Digital pictures of white and hydrogenated black TiO2, (c) HRTEM image of white TiO2, (d) HRTEM image of white TiO2, (e) UV-vis and (f) VB-XPS spectra of white and hydrogenated black TiO2. Reproduced with permission from Ref. Reference Chen, Liu, Yu and Mao4, Copyright 2011 AAAS.

Since the striking discovery of the hydrogenated black TiO2 nanoparticles, extensive researches have been conducted to enrich our understanding in the preparation and properties of various hydrogenated TiO2 nanomaterials.[ Reference Xia and Chen 20 – Reference Wang, Zhang, Wang, Yu, Wang, Zhang and Peng 75 ] Not surprisingly, it has been found that the extents of the color and optical spectrum changes,[ Reference Xia and Chen 20 – Reference Wang, Zhang, Wang, Yu, Wang, Zhang and Peng 75 ] the formation of the crystalline/disordered core/shell nanostructures,[ Reference Chen, Liu, Yu and Mao 4 , Reference Lu, Zhao, Pan, Yao, Qiu, Luo and Liu 21 – Reference Wang, Yang, Lin, Yin, Chen, Wan, Xu, Huang, Lin, Xie and Jiang 26 ] the existence of possible Ti3+ and/or oxygen vacancies,[ Reference Wang, Ni, Lu and Xu 22 – Reference Jiang, Zhang, Jiang, Rong, Wang, Wu and Pan 24 , Reference Yu, Kim and Kim 27 – Reference Rekoske and Barteau 29 ] Ti-OH groups,[ Reference Wang, Ni, Lu and Xu 22 , Reference Zheng, Huang, Lu, Wang, Qin, Zhang, Dai and Whangbo 25 , Reference Wang, Yang, Lin, Yin, Chen, Wan, Xu, Huang, Lin, Xie and Jiang 26 , Reference Lu, Yip, Wang, Huang and Zhou 28 ] Ti-H groups,[ Reference Wang, Ni, Lu and Xu 22 , Reference Zheng, Huang, Lu, Wang, Qin, Zhang, Dai and Whangbo 25 , Reference Wang, Yang, Lin, Yin, Chen, Wan, Xu, Huang, Lin, Xie and Jiang 26 , Reference Zhang, Yu, Li, Gao, Zhao, Song, Shao and Yi 30 ] and the modification of the valence band,[ Reference Chen, Liu, Yu and Mao 4 , Reference Chen, Liu, Liu, Marcus, Wang, Oyler, Grass, Mao, Glans, Yu, Guo and Mao 18 , Reference Naldoni, Allieta, Santangelo, Marelli, Fabbri, Cappelli, Bianchi, Psaro and Dal Santo 23 , Reference Lu, Yip, Wang, Huang and Zhou 28 ] heavily depend on the characteristics of the starting TiO2 nanomaterials and the hydrogenation conditions. The former includes the fabrication history (which may affect the refined surface chemical properties possibly out of the detection limits of many analytical techniques), and the physical properties (size, shape, morphology, phase, crystallinity, etc) of the starting TiO2 nanomaterials.[ Reference Lu, Yip, Wang, Huang and Zhou 28 ] The latter includes the hydrogenation temperature,[ Reference Sun, Jia, Yang, Yang, Yao, (Max) Lu, Selloni and Smith 31 , Reference Wang, Wang, Ling, Tang, Yang, Fitzmorris, Wang, Zhang and Li 41 ] time,[ Reference Yu, Kim and Kim 27 ] hydrogen pressure,[ Reference Liu, Schneider, Freitag, Hartmann, Venkatesan, Muller, Spiecker and Schmuki 32 ] the composition of the atmosphere containing the hydrogen gas,[ Reference Liu, Schneider, Freitag, Hartmann, Venkatesan, Muller, Spiecker and Schmuki 32 ] the reactor type (gas-flow reactor versus sealed reactor),[ Reference Danon, Bhattacharyya, Vijayan, Lu, Sauter, Gray, Stair and Weitz 47 ] and the sample holder materials, etc.[ Reference Xia and Chen 20 – Reference Yan, Hao, Wang, Chen, Markweg, Albrecht and Schaaf 57 ] The difference in the fabrication process will naturally result in the difference in the characteristics of the hydrogenated TiO2 nanomaterials. This nature on one hand increases the complexity of the fabrication, but on the other hand, also increases the flexibility in the tuning of the characteristics of the hydrogenated TiO2 nanomaterials. Controlling the hydrogenation process can thus lead to various desirable properties and enhanced performance in many applications.

The photocatalytic performance of TiO2 nanoparticles is benefited from the formation of the crystalline/disordered core/shell nanostructure and the long-wavelength optical absorption of the hydrogenated black TiO2 nanoparticles.[ Reference Chen, Liu, Yu and Mao 4 ] In the photocatalytic process, the photocatalyst (here, TiO2) absorbs light to produce excited electrons in the conduction band and holes in the valence band. The number of these excited electrons and holes are proportional to the amount of light the photocatalyst absorbs. The long-wavelength absorption of the hydrogenated black TiO2 nanoparticles would thus allow a large number of excited electrons and holes to be produced upon the beginning of the photocatalytic process. The crystalline core helps the effective separation of the excited electrons and holes. The difference in the electronic structures of the crystalline core and the disordered shell may generate mismatch and built-in electrical field[ Reference Xia, Zhang, Murowchick, Liu and Chen 58 ] to further facilitate charge separation and migration to the disordered shell, which may effectively trap those excited charges and extend their lifetime. The increased lifetime of the excited electrons and holes are confirmed with results from ultrafast experiments.[ Reference Pesci, Wang, Klug, Li and Cowan 59 ] Enhanced photocatalytic activities are observed on various hydrogenated TiO2 nanomaterials in producing hydrogen from water under sunlight and removing various organic pollutants.[ Reference Chen, Liu, Yu and Mao 4 ] Large enhancements in the photocatalytic activity are most commonly seen under the UV light or simulated sunlight irradiation,[ Reference Chen, Liu, Yu and Mao 4 , Reference Wang, Ni, Lu and Xu 22 , Reference Wang, Yang, Lin, Yin, Chen, Wan, Xu, Huang, Lin, Xie and Jiang 26 , Reference Yu, Kim and Kim 27 , Reference Zhang, Wang, Kim, Ma, Veerappan, Lee, Kong, Lee and Park 60 , Reference Nguyen-Phan, Luo, Liu, Gamalski, Tao, Xu, Stach, Polyansky, Senanayake, Fujita and Rodriguez 63 ] and a large success has been achieved recently under visible light irradiation.[ Reference Zheng, Huang, Lu, Wang, Qin, Zhang, Dai and Whangbo 25 , Reference Zeng, Song, Li, Zeng and Xie 49 , Reference Sinhamahapatra, Jeon and Yu 61 ] Meanwhile, there are a few reports mentioning possible decrease in the photocatalytic activities, if the hydrogenated TiO2 nanomaterials are not properly prepared.[ Reference Leshuk, Linley and Gu 37 , Reference Leshuk, Parviz, Everett, Krishnakumar, Varin and Gu 38 ] So far, hydrogenation has been conducted on TiO2 nanoparticles,[ Reference Chen, Liu, Yu and Mao 4 , Reference Lu, Zhao, Pan, Yao, Qiu, Luo and Liu 21 , Reference Sun, Jia, Yang, Yang, Yao, (Max) Lu, Selloni and Smith 31 ] nanorods,[ Reference Zhang, Zhang, Peng, Wang, Yu, Wang and Peng 48 ] nanotubes,[ Reference Zhu, Wang, Chen, Li, Zhou and Zhang 45 ] nanowires,[ Reference Shen, Uchaker, Zhang and Cao 46 ] nanosheets,[ Reference Wang, Lu, Ni, Su and Xu 35 , Reference Wang, Ni, Lu and Xu 36 ] with anatase or rutile phase,[ Reference Chen, Liu, Yu and Mao 4 , Reference Rekoske and Barteau 29 , Reference Qiu, Li, Gray, Liu, Gu, Sun, Lai, Zhao and Zhang 33 ] under high-pressure,[ Reference Chen, Liu, Yu and Mao 4 , Reference Lu, Zhao, Pan, Yao, Qiu, Luo and Liu 21 ] ambient pressure,[ Reference Rekoske and Barteau 29 , Reference Zhang, Yu, Li, Gao, Zhao, Song, Shao and Yi 30 , Reference Li, Zhang, Peng and Chen 39 ] or low-pressure[ Reference Liang, Zheng, Li, Seh, Yao, Yan, Kong and Cui 43 ] pure hydrogen environment, or hydrogen-argon,[ Reference Shin, Joo, Samuelis and Maier 44 – Reference Zhang, Zhang, Peng, Wang, Yu, Wang and Peng 48 ] hydrogen-nitrogen[ Reference He, Yang, Wang, Luo and Chen 52 – Reference Zhu, Liu and Meng 54 ] gas flow, in the temperature range from room temperature[ Reference Lu, Zhao, Pan, Yao, Qiu, Luo and Liu 21 ] to 700 °C,[ Reference Yu, Kim and Kim 27 ] with a hydrogenation time from a few minutes[ Reference Yu, Kim and Kim 27 ] to 20 days.[ Reference Lu, Zhao, Pan, Yao, Qiu, Luo and Liu 21 ] With no doubt, we can image that the so-formed TiO2 nanomaterials will display variations in their characteristics and performances. A representative study on the hydrogenation condition on the photocatalytic activity is conducted by Liu et al.[ Reference Liu, Schneider, Freitag, Hartmann, Venkatesan, Muller, Spiecker and Schmuki 32 ] They compared the hydrogenated TiO2 nanotubes and nanorods treated under several conditions: (i) an anatase TiO2 nanotube layer (air); (ii) this layer converted with Ar (Ar) or H2/Ar (H2/Ar); (iii) a high pressure H2 treatment (20 bar, 500 °C for 1 h) (HP-H2); and (iv) a high pressure H2 treatment but mild heating (H2, 20 bar, 200 °C for 5 days) (Sci Ref. Reference Chen, Liu, Yu and Mao4), and found that hydrogenated TiO2 nanotubes from high pressure H2 treatment had a high open circuit photocatalytic hydrogen production rate without the presence of a cocatalyst, in comparison with the low activity in other cases (Fig. 4).[ Reference Liu, Schneider, Freitag, Hartmann, Venkatesan, Muller, Spiecker and Schmuki 32 ] The variations in the photocatalytic activities of hydrogenated TiO2 nanomaterials seem reasonable taken into account the various fabrication conditions in those studies, and are more or less attributed in the literature to the variations of the amount of light absorbed, the existence of crystalline/disordered core/shell nanostructures, the existence of chemical defects (Ti3+ and oxygen vacancies), the formation of Ti-OH or Ti-H groups, the shift of valence/conduction band edges, and/or the introduction of intra-band electronic states in the hydrogenated TiO2 nanomaterials.[ Reference Xia and Chen 20 – Reference Wang, Zhang, Wang, Yu, Wang, Zhang and Peng 75 ] As these characteristics are primarily related to how the samples are made, the fabrication process seems to be an ultimately important aspect to achieve desirable photocatalytic performance.

Figure 4. Photocatalytic H2 production under open circuit conditions in methanol/water (50/50 vol %) with TiO2 nanotubes and nanorods treated in different atmospheres under AM1.5 (100 mW/cm2) illumination.[ Reference Liu, Schneider, Freitag, Hartmann, Venkatesan, Muller, Spiecker and Schmuki 32 ] Air, heat treatment in air at 450 °C; Ar, heat treatment in pure argon at 500 °C; Ar/H2, heat treatment in H2/Ar (5 vol %) at 500 °C; HP-H2, heat treatment in H2 at 20 bar at 500 °C; heat treatment in H2 at 20 bar at 200 °C for 5 days (following Sci Ref. Reference Chen, Liu, Yu and Mao4).[ Reference Liu, Schneider, Freitag, Hartmann, Venkatesan, Muller, Spiecker and Schmuki 32 ] Reprinted with permission from Ref. Reference Liu, Schneider, Freitag, Hartmann, Venkatesan, Muller, Spiecker and Schmuki32. Copyright 2014, American Chemical Society.

The new characteristics of the hydrogenated TiO2 nanomaterials provide new application opportunities or enhanced performances for TiO2. For example, the shallow-trapped Ti4 −n defect sites in the hydrogenated TiO2 nanoparticles bring in catalytic activity in the conversion of ethylene to high density polyethylene under mild conditions (room temperature, low pressure, absence of any activator).[ Reference Barzan, Groppo, Bordiga and Zecchina 42 ] And the oxygen vacancies produced in the hydrogenated TiO2 nanoparticles give catalytic activities in decompositing gaseous formaldehyde without light irradiation at room temperature.[ Reference Zhang, Zhang, Peng, Wang, Yu, Wang and Peng 48 ] The improved electrical conductivity of the hydrogenated TiO2 nanorods benefits the photoelectrochemical sensing of various organic compounds: glucose, malonic acid and potassium hydrogen phthalate under visible light.[ Reference Wang, Wang, Ling, Tang, Yang, Fitzmorris, Wang, Zhang and Li 41 ] Improved performances are observed when using hydrogenated TiO2 nanomaterials as the active anode materials in lithium-ion rechargeable batteries, due to the creation of oxygen vacancies,[ Reference Lu, Yip, Wang, Huang and Zhou 28 , Reference Shin, Joo, Samuelis and Maier 44 ] the existence of Ti3+ ions,[ Reference Shen, Uchaker, Zhang and Cao 46 ] the well-balanced Li+/e− diffusion,[ Reference Shin, Joo, Samuelis and Maier 44 ] the increased electronic conductivity,[ Reference Lu, Yip, Wang, Huang and Zhou 28 , Reference Li, Zhang, Peng and Chen 39 , Reference Shin, Joo, Samuelis and Maier 44 , Reference Shen, Uchaker, Zhang and Cao 46 ] reduced charge diffusion resistance,[ Reference Xia, Zhang, Wang, Zhang, Song, Murowchick, Battaglia, Liu and Chen 76 ] or the pseudocapacitive lithium storage on the disordered particle surface.[ Reference Myung, Kikuchi, Yoon, Yashiro, Kim, Sun and Scrosati 55 ] For example, the short lithium-ion diffusion path and the high electronic conductivity in the hydrogenated mesoporous TiO2 microspheres improved the lithium-ion capacity and rate capability of mesoporous TiO2 microspheres (Fig. 5),[ Reference Li, Zhang, Peng and Chen 39 ] and in Li4Ti5O12 nanowires.[ Reference Shen, Uchaker, Zhang and Cao 46 ] The increased densities of charge carrier and hydroxyl groups, and the higher electrical conductivity in the hydrogenated TiO2 nanotubes also help the supercapacitive performance of TiO2.[ Reference Lu, Wang, Zhai, Yu, Gan, Tong and Li 17 ] Meanwhile, these characteristics also help to deposit Pt nanoparticles on the surface and improve the performance and durability as electrode materials in fuel cells.[ Reference Zhang, Yu, Li, Gao, Zhao, Song, Shao and Yi 30 ]

Figure 5. (a) Cyclic voltammetry profiles of the hydrogenated (H-TiO2) and pure (A-TiO2) anatase microspheres at a scan rate of 0.5 mV/s. Galvanostatic discharge–charge profiles of the (b) H-TiO2 and (c) A-TiO2 microspheres at various rates. (d) Comparison of the rate performance of the H-TiO2 and A-TiO2 microspheres.[ Reference Li, Zhang, Peng and Chen 39 ] Reprinted with permission from Ref. Reference Li, Zhang, Peng and Chen39. Copyright 2013 The Royal Society of Chemistry.

The oxygen vacancies introduced to the hydrogenated TiO2 nanotubes lift the Fermi level, improve the electrical conductivity, and reduce the work function to decrease the field-penetration barrier at the surface resulting in easy electron emission in under electrical bias.[ Reference Zhu, Wang, Chen, Li, Zhou and Zhang 45 ] As the crystalline/disordered core/shell nanostructure is formed for hydrogenated TiO2 nanoparticles, there is apparent electronic structural mismatch between the crystalline phase and the disordered phase.[ Reference Chen, Liu, Yu and Mao 4 , Reference Xia, Zhang, Oyler and Chen 77 , Reference Xia, Zhang, Oyler and Chen 78 ] The interface in between is expected to have structural and chemical defects with dangling bonds and charge imbalance. Meanwhile, the various defects help the charge diffusion and transport with smaller resistance. Interfacial band bending and polarization are expected in the boundaries between these phases.[ Reference Dong, Ullal, Han, Wei, Ouyang, Dong and Gao 79 ] The propagation of the microwave electromagnetic field through the material will cause rapid switching of the polarizing direction and charge accumulation at these interfaces based on a collective-movement-of-interfacial-dipoles (CMID) mechanism.[ Reference Xia, Zhang, Oyler and Chen 77 , Reference Xia, Zhang, Oyler and Chen 78 ] Hydrogenated TiO2 nanoparticles can thus show excellent microwave absorption performance.[ Reference Xia, Zhang, Oyler and Chen 77 , Reference Xia, Zhang, Oyler and Chen 78 ] Changing the hydrogenation condition can tune the anatase/rutile ratios and the size of the individual core/shell nanoparticles to achieve microwave absorption with adjustable frequencies.[ Reference Xia, Zhang, Oyler and Chen 78 ] Figure 6 shows a good example of the microwave absorption of hydrogenated TiO2 nanoparticles.[ Reference Xia, Zhang, Oyler and Chen 77 , Reference Xia, Zhang, Oyler and Chen 78 ] This discovery has been expanded to hydrogenated ZnO and BaTiO3 nanoparticles for enhanced microwave absorption.[ Reference Tian, Yan, Xu, Wallenmeyer, Murowchick, Liu and Chen 80 , Reference Xia, Cao, Oyler, Murowchick, Liu and Chen 81 ]

Figure 6. (a) The mechanism of collective interfacial polarization amplified microwave absorption (CIPAMA) of hydrogenated TiO2 nanoparticles.[ Reference Xia, Zhang, Oyler and Chen 77 ] The collective movements of interfacial dipoles (CMID) at the anatase/rutile and crystalline/disordered interfaces amplify the response to the incoming electromagnetic field and thus induce enhanced microwave absorption performance. The positions of the electronic band structure of the disordered layer are assumed to lie between those of anatase and rutile phases. CBE: conduction band edge, VBE: valence band edge. Reprinted with permission from Ref. Reference Xia, Zhang, Oyler and Chen77. Copyright 2013 Wiley-VCH. (b) Reflection loss of pristine and hydrogenated TiO2 nanocrystals.[ Reference Xia, Zhang, Oyler and Chen 78 ] Reprinted with permission from Ref. Reference Xia, Zhang, Oyler and Chen78. Copyright 2014 Materials Research Society.

Hydrogenated TiO2 nanoparticles have recently been demonstrated with promising medical application due to their extended absorption in the infrared region.[ Reference Ren, Yan, Zeng, Shi, Gong, Schaaf, Wang, Zhao, Zou, Yu, Chen, Brown and Wu 82 , Reference Mou, Lin, Huang, Chen and Shi 83 ] They can efficiently convert the near-infrared light energy into thermal energy and produce localized heat island.[ Reference Ren, Yan, Zeng, Shi, Gong, Schaaf, Wang, Zhao, Zou, Yu, Chen, Brown and Wu 82 ] After they are injected near the cancer cells and irradiated with near-infrared light, the locally produced heat can effectively kill the cancer cells without affecting the adjacent healthy cells.[ Reference Ren, Yan, Zeng, Shi, Gong, Schaaf, Wang, Zhao, Zou, Yu, Chen, Brown and Wu 82 ] This process is named as photothermal therapy. Compared with the UV excitation requirement, the hydrogenated TiO2 only needs near-infrared excitation. This increases the penetration depth under the skin, and prevents the damage caused by the UV irradiation on the skin at the same time. Thus, hydrogenated TiO2 nanoparticles may prove to be very useful in medical applications.

Other hydrogenated oxide nanomaterials

ZnO

Hydrogenated ZnO has also been studied as well.[ Reference Xia, Cao, Oyler, Murowchick, Liu and Chen 81 , Reference Strzhemechny, Mosbacker, Look, Reynolds, Litton, Garces, Giles, Halliburton, Niki and Brillson 84 – Reference Tang, Li, Zhou, Chen and Chen 92 ] Here, only some recent works are given as examples. Similar to hydrogenation on TiO2, hydrogenation introduces visible-light absorption,[ Reference Xia, Wallenmeyer, Anderson, Murowchick, Liu and Chen 86 ] oxygen vacancies,[ Reference Xia, Wallenmeyer, Anderson, Murowchick, Liu and Chen 86 ] zinc vacancies,[ Reference Xia, Wallenmeyer, Anderson, Murowchick, Liu and Chen 86 , Reference Xue, Liu, Wang and Wu 91 ] interstitial hydrogen,[ Reference Strzhemechny, Mosbacker, Look, Reynolds, Litton, Garces, Giles, Halliburton, Niki and Brillson 84 , Reference Lu, Wang, Xie, Shi, Li, Tong and Li 85 ] and increased carrier densities.[ Reference Strzhemechny, Mosbacker, Look, Reynolds, Litton, Garces, Giles, Halliburton, Niki and Brillson 84 ] The interstitial hydrogen increases the carrier densities,[ Reference Strzhemechny, Mosbacker, Look, Reynolds, Litton, Garces, Giles, Halliburton, Niki and Brillson 84 ] improves the charge transport in the bulk and the charge transfer at the solid/liquid interface.[ Reference Lu, Wang, Xie, Shi, Li, Tong and Li 85 ] Meanwhile, the oxygen vacancies help the trapping of holes and thus the charge separation, and reduce the electron-hole recombination. These characteristics bring in higher photocatalytic activities in both photocatalytic hydrogen generation and pollution removal. Meanwhile, as hydrogenation improves the electrical conductivity[ Reference Myong and Lim 87 ] and electrochemical activity of ZnO, hydrogenated ZnO-coated MnO2 nanowires have improved supercapacitor performance with enhanced capacity and stability.[ Reference Yang, Xiao, Li, Ding, Qiang, Tan, Mai, Lin, Wu, Li, Jin, Liu, Zhou, Wong and Wang 88 , Reference Yu, Sun, Sun, Lu, Wang, Hu, Qiu and Lian 89 ] Under suitable hydrogenation conditions, the hydrogen introduced can passivate deep oxygen vacancies, but increase the shallow oxygen vacancies, thus, after hydrogenation, the defect-related peak at 2.10 eV is no longer present in the room temperature photoluminescence spectrum, the peak intensity at 2.43 eV is unchanged, and the intensity of the emission peak at 3.27 eV increases significantly, resulting in an obvious emission spectrum and color change.[ Reference Kim, Oh, Kim and Yang 90 ] Similar to hydrogenated TiO2, hydrogenated ZnO also displays impressive microwave absorption performance.[ Reference Xia, Cao, Oyler, Murowchick, Liu and Chen 81 ] In addition, hydrogenation seems to have a large impact on the ferromagnetism of ZnO nanoparticles.[ Reference Xue, Liu, Wang and Wu 91 ] Hydrogenated ZnO nanoparticles display room-temperature ferromagnetism and their ferromagnetism can be switched between “on” and “off” by annealing in hydrogen or oxygen, respectively.[ Reference Xue, Liu, Wang and Wu 91 ] The formation of Zn vacancy and OH bonding by hydrogenation is favored in the hydrogenation process due to the low formation energy, and lead to a magnetic moment of 0.57 µb, while the ferromagnetism is not induced by the oxygen vacancies.[ Reference Xue, Liu, Wang and Wu 91 ] It is found that hydrogenation depends on the thickness of ZnO nanosheets. Hydrogenated ZnO nanosheets preserve the wurtzite configuration, instead of the polar {0001} surfaces. Full hydrogenation is favorable for thinner nanosheets, while semihydrogenation is preferred for thicker nanosheets. The transition from semiconductor to magnetism depends upon surface hydrogenation and thickness.[ Reference Tang, Li, Zhou, Chen and Chen 92 ]

CeO2 and Ni x CeO2+x

Hydrogenation on CeO2 nanoparticles has also been recently studied.[ Reference Jiang, Wang, Zheng and Zhang 93 , Reference Weng, Liu, Yin, Fang, Li, Altman, Fan, Li, Cheng and Wang 94 ] Grey CeO2 nanoparticles are obtained after hydrogenation due to the surface plasma resonance-like visible-light absorption.[ Reference Jiang, Wang, Zheng and Zhang 93 ] Oxygen vacancies are created on the surface and in the bulk. Disordered surface is obtained after annealing in air.[ Reference Jiang, Wang, Zheng and Zhang 93 ] The hydrogenated CeO2 nanoparticles display enhanced performance as well as improved water resistance in photocatalytic oxidation of gaseous hydrocarbons.[ Reference Jiang, Wang, Zheng and Zhang 93 ] Hydrogenation has been employed in Ni x CeO2+x nanoparticles to create unique metal/oxide interface.[ Reference Weng, Liu, Yin, Fang, Li, Altman, Fan, Li, Cheng and Wang 94 ] The formed Ni/CeO2 interface modifies the hydrogen binding energy and facilitates the water dissociation to achieve a high activity in electrocatalytic hydrogen generation as shown in Fig. 7.[ Reference Weng, Liu, Yin, Fang, Li, Altman, Fan, Li, Cheng and Wang 94 ]

Figure 7. (a) Schematic illustration of the hydrogenation-induced structural change from Ni x CeO2+x to Ni/CeO2 on carbon nanotubes. (b) The electrochemical polarization curves for hydrogen evolution reactions on Ni x CeO2+x -CNT, Ni/CeO2-CNT, Ni-CNT, and Pt/C electrodes. CNT: carbon nanotube.[ Reference Weng, Liu, Yin, Fang, Li, Altman, Fan, Li, Cheng and Wang 94 ] Reprinted with permission from Ref. Reference Weng, Liu, Yin, Fang, Li, Altman, Fan, Li, Cheng and Wang94. Copyright 2015, American Chemical Society.

VO2

VO2 is a material with strong correlation, and undergoes a metal-to-insulator transition at 67 °C from a rutile metallic state to a monoclinic, insulating state. Hydrogenation can strongly modify the metal-insulator transition on the nanoscale.[ Reference Wei, Ji, Guo, Nevidomskyy and Natelson 95 ] This transition becomes completely reversible with hydrogen doping and can eventually disappear with large doping content.[ Reference Wei, Ji, Guo, Nevidomskyy and Natelson 95 ] The structure of the hydrogenated VO2 is distorted from the rutile structure and it energetically favors the metallicity.[ Reference Wei, Ji, Guo, Nevidomskyy and Natelson 95 ] The hydrogen doping is believed by means of spillover and involves rapid diffusion along the rutile c-axis.[ Reference Chippindale, Dickens and Powell 96 – Reference Wu, Feng, Feng, Dai, Peng, Zhao, Yang, Si, Wu and Xie 98 ]

WO3

Hydrogenation brings in similar optical, structural, and chemical property changes to WO3 as in TiO2: optical absorption in the visible light region, obvious decrease in crystallinity, introduction of oxygen vacancies and lower valence-state metal ions W5+, enhanced photoelectrochemical activity and stability for water oxidation.[ Reference Wang, Ling, Wang, Yang, Wang, Zhang and Li 99 ] The oxygen-deficient WO3 (WO2.9) displays enhanced activity in electrochemical hydrogen evolution reaction, due to the tailored electronic structure from local atomic structure modulations.[ Reference Li, Liu, Pan, Wang, Yang, Zheng, Hu, Zhao, Gu and Yang 100 ]

MoO3

MoO3 can be used as a hole-injection layer in organic light emitting diodes and photovoltaics due to its decrease of the hole-injection/extraction energy barrier at the anode/organic interfaces. Hydrogenation treatment displays a unique advantage over other methods.[ Reference Vasilopoulou, Kostis, Douvas, Georgiadou, Soultati, Papadimitropoulos, Stathopoulos, Savaidis, Argitis and Davazoglou 101 ] Hydrogenation can create oxygen vacancies and hydroxyl groups in MoO3 and introduce bandgap states to improve the charge injection efficiency and thus the device performance.[ Reference Vasilopoulou, Kostis, Douvas, Georgiadou, Soultati, Papadimitropoulos, Stathopoulos, Savaidis, Argitis and Davazoglou 101 ]

TaON

TaON has recently been shown as a promising photocatalyst in photocatalytic water splitting. Hydrogenation improves its visible-light absorption, increases charge density, reduces electron-hole recombination, and enhances the photocatalytic activity in photocatalytic hydrogen generation.[ Reference Hou, Cheng, Yang, Takeda and Zhu 102 ]

TiOF2

TiOF2 has been studied as a possible anode materials for lithium-ion rechargeable batteries. Hydrogenation of TiOF2 nanoparticles leads to the formation of smaller particle sizes, i.e., along the (001) direction, increases oxygen vacancies, and improves the charge/discharge capacity and rate performance.[ Reference He, Wang, Yan, Tian, Liu and Chen 103 ] Although structural defects seem to be introduced in the TiOF2 after hydrogenation, the hydrogenation does not reduce the electrical resistance, and increase the carrier density of the TiOF2 nanoparticles.[ Reference He, Wang, Yan, Tian, Liu and Chen 103 ] The improved battery performance is mainly due to the increased electrochemically active surface areas and the reduced charge diffusion length benefited from the decreased particle size after hydrogenation.[ Reference He, Wang, Yan, Tian, Liu and Chen 103 ]

MnMoO4

Hydrogenation has been shown to improve the activity of electrochemically inert MnMoO4 for both hydrogen evolution and supercapacitive electrical energy storage.[ Reference Yan, Tian, Murowchick and Chen 104 ] Hydrogenation can induce partial amorphorization in MnMoO4 and increase the electrochemical active surface area. The charge transfer resistance decreases for both capacitive charge storage and hydrogen evolution reaction (HER). As a result, the onset overpotential for the HER reaction is largely reduced and capacity for charge storage is largely enhanced at the same time.[ Reference Yan, Tian, Murowchick and Chen 104 ]

NiO

Ni and nickel hydr(oxide) compounds are explored as promising electrode materials for electrochemical production of hydrogen from water by electrolysis.[ Reference Weng and Chen 105 ] Hydrogenation has been shown to convert NiO nanosheets into Ni/NiO core/shell nanosheets.[ Reference Yan, Tian and Chen 106 ] In this case, NiO nanosheets are reduced to metallic Ni nanosheets first, and then oxidized to form crystalline/amorphous Ni/NiO core/shell nanosheets when exposed to air. This unique structure is shown in Fig. 8.[ Reference Yan, Tian and Chen 106 ] The amorphous NiO surface lowers the energy barrier for hydrogen evolution, reduces the desorption energy, while the metal core helps to reduce the electrical resistance.[ Reference Yan, Tian and Chen 106 ] The hydrogenation also increases the electrochemically active surface area of the catalyst and the Ni/NiO metal/metal oxide interface. Overall the catalytic activity in hydrogen evolution is enhanced.[ Reference Yan, Tian and Chen 106 ]

Figure 8. (a) SEM and (b, c) TEM images of hydrogenated Ni/NiO crystalline/amorphous core/shell nanosheets.[ Reference Yan, Tian and Chen 106 ] Reprinted with permission from Ref. Reference Yan, Tian and Chen106. Copyright 2015, Elsevier.

Co3O4

Similar to the changes induced on NiO nanosheets, hydrogenation is also shown to convert Co3O4 nanosheets to Co/Co3O4 crystalline/amorphous core/shell nanosheets.[ Reference Yan, Tian, He and Chen 107 ] These nanosheets display impressive activity in electrochemical hydrogen evolution reaction with an overpotential of ~90 mV in 1 m KOH in achieving a current density of 10 mA/cm2.[ Reference Yan, Tian, He and Chen 107 ] The good activity is likely due to the low gas desorption resistance and the fast charge-transfer kinetics on the surface of the electrode caused by the hydroxyl-enriched amorphous cobalt oxide caused by the hydrogenation treatment.[ Reference Yan, Tian, He and Chen 107 ] Oxygen vacancies however, cause a poor performance. Typical microscopy images and the catalytic activity of the hydrogenated Co/Co3O4 nanosheets are shown in Fig. 9.[ Reference Yan, Tian, He and Chen 107 ]

Figure 9. (a) SEM and (b, c) TEM images of hydrogenated Co/Co3O4 crystalline/amorphous core/shell nanosheets, (d) The electrochemical polarization curves for hydrogen evolution reactions on Ni, Co3O4, Co/Co3O4, and Pt/C.[ Reference Yan, Tian, He and Chen 107 ] Reprinted with permission from Ref. Reference Yan, Tian, He and Chen107. Copyright 2015, American Chemical Society.

Ni x Co3−x O4

Similar to NiO and Co3O4, hydrogenation on nanowires of their alloy Ni x Co3−x O4 can lead to the formation of NiCo/NiCoO x heteronanostructure.[ Reference Yan, Li, Lyu, Song, He, Niu, Liu, Hu and Chen 108 ] And the corresponding activities in oxygen and hydrogen evolution reactions can be tuned after hydrogenation.[ Reference Yan, Li, Lyu, Song, He, Niu, Liu, Hu and Chen 108 ]

Summary and perspective

In summary, hydrogenation has opened many opportunities in oxide nanomaterials and has become a new tool for scientists to manipulate the properties and applications of oxide and non-oxide nanomaterials. Hydrogenation treatment of oxide nanomaterials can introduce many unique structural, chemical, electronic, and other property changes. Those property changes can largely improve their performance in many applications such as photocatalysis, electrocatalysis, photoelectrocatalysis, rechargeable batteries, supercapacitors, and also trigger some new applications such as photothermal image/therapy, field emission, ferromagnetism, and microwave absorption. Further studies may reveal more interesting properties and applications.

Tuning the hydrogenation condition can control the chemical reaction and the final product, and generate new structures and chemical composition. However, understanding of the hydrogenation reaction itself is far from satisfactory, although the property changes caused by the hydrogenation treatment are well studied. Studies on the chemical reaction kinetics, in situ or ex situ, will help us to better understand and thus control the property changes by hydrogenation, which may reveal new applications. The large visible-light absorption induced by hydrogenation in some oxide nanomaterials has not yet been efficiently utilized. Continuing exploring the synthetic approaches and procedures may provide a promising future as seen from the recent developments, which sometimes are accompanied with frustrations and excitements. The mechanical and biological properties of the hydrogenated oxide nanomaterials are not yet studied. Studies in those properties may reveal better or new applications. For example, the crystalline/disordered nanoparticles may be better building units for constructing stronger bulk materials. In addition, the surface wettability of hydrogenated nanoparticles is not yet explored. As hydrogenation changes the oxygen vacancies and hydroxyl groups, it is expected that the surface wettability will be affected as well. Meanwhile, expansion of hydrogenation treatment to other oxide and non-oxide nanomaterials or their combinations may open new opportunities. For example, hydrogenation of FeP nanoparticles leads to an apparent reduction in the overpotential for hydrogen evolution,[ Reference Tian, Yan and Chen 109 ] and complex metal/oxide FeNi3/NiFeO x nanocomposites are obtained as highly efficient bifunctional electrocatalysts for overall water splitting with a small potential of 1.55 V to reach the critical current density of 10 mA/cm2 after hydrogenation on NiFeO x nanosheets.[ Reference Yan, Tian, Li, Atkins, Zhao, Murowchick, Liu and Chen 110 ]

Acknowledgments

X. C. thanks the financial support from the U.S. National Science Foundation (DMR-1609061), and the College of Arts and Sciences, University of Missouri − Kansas City. X. Y. thanks the funds provided by the University of Missouri-Kansas City, School of Graduate Studies. L. Tian and X. Tan appreciate the China Scholarship Council for financial support. L. L. acknowledges the support from the National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars of China (No. 61525404).