Skipping breakfast has become the norm in modern-day India because of changes in family lifestyle. When this happens largely among children, it can result in their suboptimal growth and development – a factor important to the future human resource development of the country. It is estimated that several children attend school daily without having eaten any breakfast and many more consume an inadequate breakfastReference Gross, Bronner, Welch, Dewberry-Moore and Paige1. Skipping breakfast can affect children's physical and mental developmentReference Sethi and Dangwal2. Skipping breakfast may hinder child growth because the body is forced to call upon stores of protein to meet energy requirements. Behavioural problems in children – including decreased attentiveness, irritability and hyperactivity – have been reported to be associated with the transient hunger resulting from missing breakfastReference Grantham McGregor, Chang and Walker3, Reference Pollitt, Cueto and Jacoby4. Breakfast enhances cognition and academic performance. Missing breakfast has adverse effects on cognition, particularly the speed of information retrieval in working memoryReference Pollitt5, Reference Chandler, Walker, Connolly and Grantham-McGregor6, whereas breakfast consumption influences processes in the formation and retrieval of new memories. Thus skipping breakfast reduces the learning capacity of children. Providing breakfast to students at school has been reported to improve some cognitive functions, particularly in undernourished childrenReference Grantham McGregor, Chang and Walker3.

Eating breakfast improves the overall quality and nutrient intake of the diet. Several investigators have suggested that omission of breakfast and/or consumption of an inadequate breakfast may be factors contributing to dietary inadequacies, and that the accompanying nutritional losses are rarely made up by other meals during the remainder of the dayReference Colic Baric and Satalic7, Reference Nicklas, Bao, Webber and Berenson8. The dietary intake patterns of children have been a special concern since it was found that eating patterns formed in early life are likely to persist into adulthood.

The aims of the present study were to ascertain the breakfast habits of a cross-sectional sample of urban Indian schoolchildren aged 10–15 years and to assess the quality of this meal and its relationship to the food consumption patterns for the full day.

Materials and methods

Subjects and study area

This study was conducted on 802 schoolchildren (56% male) aged 10–15 years. Their breakfast eating patterns were determined using dietary recall, and the impact of breakfast habit on growth was assessed by anthropometric measurements. Four schools located in Secunderabad city in Andhra Pradesh, India were selected at random for inclusion in the study. All children in these schools (both boys and girls) in the age group of 10–15 years were included to achieve the desired sample size.

Anthropometry

Anthropometric measurements (height, weight and mid upper-arm circumference) were recorded using standard procedures. Height was measured with an anthropometric vertical rod according to standard methodsReference Jelliffe and Jelliffe9. Weight was recorded with an electronic personal scale with a maximum capacity of 150 kg and a least count of 200 g. Mid upper-arm circumference was measured to the nearest millimetre using a fibreglass tape.

Dietary assessment

The study protocol included socio-economic family background, dietary intake and regularity of consuming breakfast. The diet survey was conducted using an oral questionnaire (24-hour recall method), which consisted of listing all foods and beverages consumed during the previous 24 h using the standard cups developed by the National Institute of Nutrition, Hyderabad, IndiaReference Thimmayamma10. Data on the food consumption of older children (13–15 years) were collected using an in-classroom questionnaire. The schedule for younger children (10–12 years) was completed by the parents and the child together. The dietary intakes obtained in terms of standardised cups were converted into quantities of raw food ingredients and the nutrient content was then computed using the Indian food composition tablesReference Gopalan, Rama Sastri and Balasubramanian11. The Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) for Indians were used for comparison12, and nutrient adequacy ratios (NARs) were also calculatedReference Guthrie and Scheer13.

To assess the breakfast eating patterns of the subjects, the foods and beverages consumed for breakfast over a week were determined. The subjects were given a schedule to enter details of foods and beverages (including quantities) consumed over a period of one week. The completed schedules were returned to the investigator at the end of the week.

Statistical methods

The study data were subjected to statistical analysis with appropriate tools using the SPSS for Windows software package (version 10.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to determine means and standard deviations, while correlation coefficients were used for analysing and interpreting the data to enable inferences to be drawn.

Results and discussion

The foods consumed varied from traditional south Indian breakfast items based on cereal/pulse combinations like dosa and idli to cereal-based items like chapatti (unleavened whole-wheat bread), puri (unleavened whole-wheat bread that is deep-fried), bread, upma (based on wheat semolina) and rice. The beverages commonly consumed were milk, coffee, tea and fruit juice. Chapatti was the most frequently consumed breakfast item followed by dosa and idli.

Of all the children studied, 42.8% did not skip breakfast at all, 11.6% skipped breakfast once in two days, 8.0% skipped breakfast once in three days, 25.1% skipped breakfast once a week, 10.8% skipped breakfast once in two weeks and 1.7% skipped breakfast every day. The reasons for skipping breakfast were listed as waking up late, not feeling hungry, disliking the food offered and busy doing homework. A larger number of girls were found to consume breakfast regularly compared with boys.

A positive correlation was found between the frequency of skipping breakfast and weight status (r = 0.899). Among the children who did not skip breakfast at all, only 9.9% were underweight and 83.3% were normal-weight (the 50th percentile of the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) standards was used for comparison). Among the children who skipped breakfast every day, 53.8% were underweight and 38.8% were normal-weight. A higher percentage of children who skipped breakfast once in two days (55.9%) and once in three days (56.9%) was found to be underweight compared with the children who skipped breakfast only once a week (24.8%) (Table 1).

Table 1 Weight status of the schoolchildren in relation to the frequency of skipping breakfast

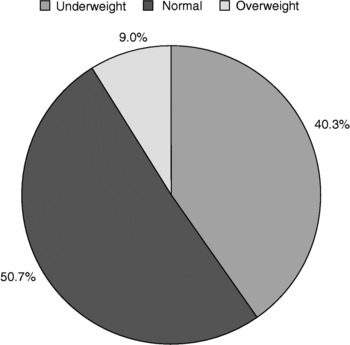

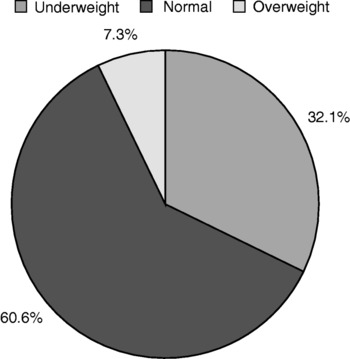

The incidence of malnutrition was studied separately in boys and girls. Just over half of the boys and almost two-thirds of the girls were found to have normal weight as compared with the 50th percentile of NCHS standards. However, the inadequate energy intake (see below) was reflected in a high incidence of malnutrition in both boys and girls; 40.3% of the boys and 32.1% of the girls studied were found to be underweight (Figs 1 and 2).

Fig. 1 Incidence of malnutrition in boys

Fig. 2 Incidence of malnutrition in girls

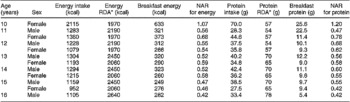

Mean nutrient intakes calculated from 24-hour recalls revealed that the children's diets were inadequate compared with the recommended values for energy and protein12 (Table 2). The only exception was 10-year-old girls; both protein and energy intakes of this group were higher than RDA levels. For all other age groups, energy and protein intakes were lower than recommended for both boys and girls. The energy intake values indicated a daily deficit of 600–900 kcal. The mean energy and protein values for breakfast alone indicate that those who did not skip breakfast met one-quarter to one-third of their total energy and protein requirements. A significant number of the study children skipped breakfast and this could be the major reason for the inadequate daily energy and protein intakes. These findings are consistent with previous studies which have reported that average total energy intake was significantly lower for children who did not consume breakfast before schoolReference Pollitt, Cueto and Jacoby4, Reference Aranceta, Serra-Majem, Ribas and Perez-Rodrigo14.

Table 2 Mean energy and protein intakes of the schoolchildren

RDA – Recommended Dietary Allowance; NAR – nutrient adequacy ratio.

* As suggested by the Indian Council for Medical Research, 200412.

Values of NAR of 0.66 and above reflect adequate dietary intake of a particular nutrient. The NAR values for energy and protein indicated that only 10-year-old girls and 11-year-old girls could meet their energy and protein requirements (Table 2). For all other age groups, energy and protein NAR values were significantly lower, reflecting inadequate intake.

Children from higher socio-economic groups and those from families whose parents had higher education levels showed higher proportions of adequate energy and protein intakes (P < 0.05). This is in agreement with a previous studyReference Haapalahti, Mykkanen, Tikkanen and Kokkonen15 that reported unhealthy food habits to be more common among families of low socio-economic status. Of the children in the present study, 33% had working mothers. However, there was no significant difference between the adequacy of intakes of children of working and non-working mothers.

There was a significant correlation (P < 0.05) between energy intake and weight and between breakfast energy and weight among 11- and 12-year-old boys. For 11-year-old boys, a significant correlation (P < 0.05) was also observed between weight and breakfast protein. A similar trend was exhibited among 13-year-old boys. Among girls, there was a significant correlation (P < 0.05) between weight and energy intake and between weight and breakfast energy. Weight and protein intake were also correlated significantly (P < 0.05) in 11- and 12-year-old girls; and positive correlations were found between weight and energy intake and between weight and breakfast energy among 14- and 15-year-old girls.

All of these trends show that breakfast consumption had a direct impact on the weight status of the schoolchildren. The mean daily intakes of energy and protein of children who consumed breakfast were significantly greater than those of children who skipped breakfast. A higher percentage of children who skipped breakfast did not meet two-thirds of the RDA compared with those who consumed breakfast. Thus the low weight of breakfast skippers may be partly attributed to their low energy intake and deficiency of essential nutrients, which were otherwise provided through breakfast. A previous study of breakfast eating patterns of Indian schoolchildren reported that breakfast eaters showed deficient intakes of iron, β-carotene and niacin, whereas breakfast skippers had distinctly lower values than breakfast eatersReference Sethi and Dangwal2. Moreover, that study found a positive correlation between energy intake and weight and also between protein intake and weight for breakfast eatersReference Sethi and Dangwal2.

Our study reveals that breakfast could be a valuable contributor of specific nutrients in the daily dietary intake of school-aged children. Over half of the subjects studied skipped breakfast frequently, the main reason – getting up late – indicating that better attention to time management was needed both by parents and children. Subjects who consumed breakfast had higher daily intakes of energy and protein than children who skipped breakfast. Children who skipped breakfast did not compensate by increasing energy intake at other meals during the day. These data confirm the importance of breakfast to overall dietary quality and adequacy in school-aged children. The results of the study indicate that there is a strong need to educate urban parents with respect to proper distribution of meals and the importance of providing at least a third of the day's requirement through breakfast.

Acknowledgements

The authors are extremely grateful to the Management Committee of Kasturba Gandhi Degree and PG College for Women for financing this research project. They are also indebted to the staff and students of the schools where this work was undertaken for their cooperation and support.