The Irrawaddy dolphin Orcaella brevirostris is a range-restricted, facultative freshwater species that inhabits coastal, estuarine and freshwater habitats in disjunct populations from India to South-east Asia. The Iloilo-Guimaras Straits subpopulation is one of three known O. brevirostris subpopulations in the Philippines and the second to be declared Critically Endangered (Dolar et al., 2018, dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T123095978A123095988.en). This subpopulation of 13–25 individuals was discovered in 2007, and is believed to be in decline. This decline is likely to be exacerbated should the Philippine government pursue plans to construct the Panay–Guimaras–Negros bridges under their ‘Build, Build, Build’ agenda to boost interconnectivity for economic development.

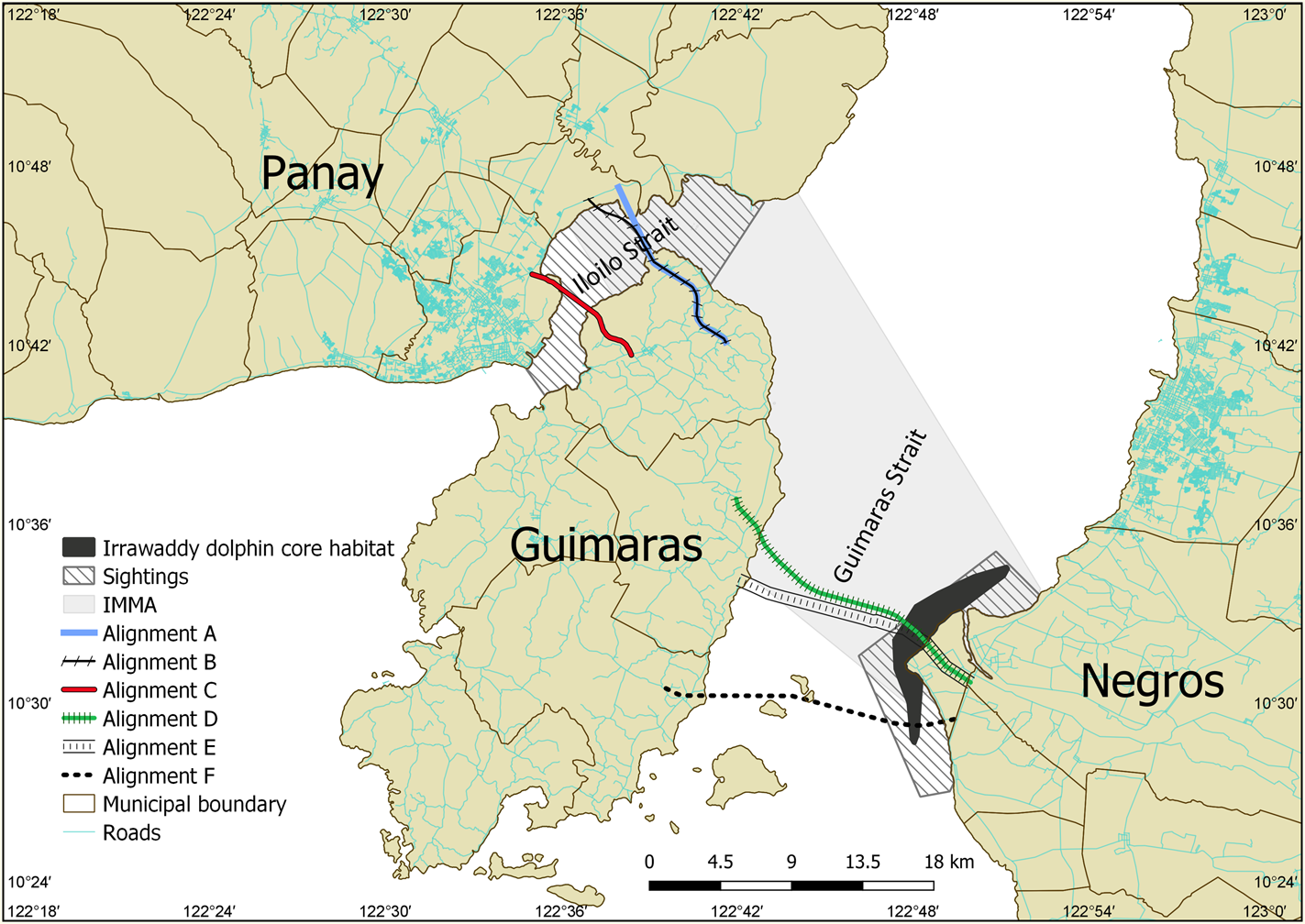

A feasibility study of the proposed bridges stated that the construction phase would have few significant effects on the marine fauna. However, the proposed bridges will affect an Important Marine Mammal Area and the known range of this O. brevirostris subpopulation (Fig. 1). Specifically, the potential bridge alignment D directly bisects the species’ core habitat (de la Paz et al., 2020, Raffles Bulletin of Zoology, 68, 562–573). We know from the case of the Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin Sousa chinensis in the Pearl River Delta affected by the Hong Kong-Macau-Zhuhai bridge (Karzmarski et al., 2016, Advances in Marine Biology, 73, 27–64) that the cumulative effects of existing threats and extensive construction in the species’ habitat will have irreversible impacts on its long-term survival.

Fig. 1 The known range of the Iloilo-Guimaras Straits subpopulation of the Irrawaddy dolphin Orcaella brevirostris in the central Philippines includes parts of the Iloilo and Guimaras Straits. An ambitious project to construct bridges connecting the islands of Panay, Guimaras and Negros would bisect a recognized Important Marine Mammal Area (IMMA) and the core habitat of this Critically Endangered subpopulation of O. brevirostris. This map summarizes all known spatial data on the subpopulation. The alignments indicate the different bridge positions being considered. Important Marine Mammal Area boundaries are from Marine Mammal Protected Area Task Force (2020, marinemammalhabitat.org).

The Iloilo–Guimaras Straits subpopulation of O. brevirostris already faces grave threats from bycatch, collision with boats, illegal fishing, and habitat degradation. During the construction phase of these bridges we would expect an increase in noise pollution from pile driving and the ferrying of materials, and consequent negative effects on the bio-acoustic behaviour of the dolphins and an increased risk of collisions with boats. We expect long-term effects, such as sediment bed changes and scouring, changes in water movement and current, and changes in prey dynamics, to affect the local environment even after the bridges are built. In time, such effects will be felt by local residents who rely on these straits for their livelihood.

Yet, there is still hope. On 6 August 2020, government officials announced the shelving of the Guimaras–Negros segment of this large-scale infrastructure project, citing the presence of mangroves and dolphins. This announcement followed a public outcry that questioned the validity of the preliminary assessment as it had ignored the presence of Irrawaddy dolphins within the proposed construction sites. However, this change offers only temporary relief to this subpopulation, considering the extensive threats to its long-term survival. We must, collectively, continue to give due attention to the precarious status of this subpopulation to ensure it remains extant.