Introduction

In light of ongoing environmental degradation, the increase in extreme weather events, the tangible effects of the climate crisis, and questions of power and justice that are deeply embedded in all these developments, the debate on shaping liveable futures is gaining new vigour and contour. However, even if the challenges and expected scenarios have been — despite all the uncertainty — pointed out scientifically (e.g. Richardson et al., Reference Richardson, Steffen, Lucht, Bendtsen, Cornell, Donges, Drüke, Fetzer, Bala, von Bloh, Feulner, Fiedler, Gerten, Gleeson, Hofmann, Huiskamp, Kummu, Mohan, Nogués-Bravo, Petri, Porkka, Rahmstorf, Schaphoff, Thonicke, Tobian, Virkki, Wang-Erlandsson, Weber and Rockström2023) the steps, measures, and paths towards shaping a more sustainable world are highly controversial in socio-political terms. The narratives include a scenario of control (i.e. comprehensive adaptation strategies), one of modernisation (i.e. technological advances), and one of social-ecological transformation (i.e. deep structural change towards a CO2-reducing, resource-conserving, and socially just society) (Adloff & Neckel, Reference Adloff, Neckel, Dörre, Rosa, Becker, Bose and Seyd2019). This spectrum of negotiating a sustainable future is characterised by conflicts of interest and mentality at different levels and is reinforced by power effects, moralisation, and externalisation (Eversberg et al., Reference Eversberg, Fritz, von Faber and Schmelzer2024). Accordingly, comprehensive participation in the negotiation and design of transformation processes is a central condition for success (ibid.).

In this context, great importance is attached to educational practices for exploring possible futures and the success of societal transformation (Bormann et al., Reference Bormann, Singer-Brodowski, Janina, Wanner, Schmitt and Blum2022). However, educational processes are caught between the urgency of a comprehensive societal shift on the one hand and the appropriation of education for the instrumental execution of a political top-down agenda for political sustainability on the other hand (Hursh, Henderson & Greenwood Reference Hursh, Henderson and Greenwood2015). These paradoxes and antinomies are often resolved in a one-sided instrumental way in specific educational contexts (Boström et al., Reference Boström, Andersson, Berg, Gustafsson, Gustavsson, Hysing, Lidskog, Löfmarck, Ojala, Olsson, Singleton, Svenberg, Uggla and Öhman2018), even if education for sustainable development (ESD) advocates for pluralistic education (Tryggvason et al., Reference Tryggvason, Öhman and van Poeck2023). Thus, (education for) sustainable development has a far-reaching tendency towards responsibilising (i.e. making individuals responsible for sustainability and thus contributing to a depoliticisation of the approach) (Sund & Öhmann, Reference Sund and Öhmann2013; Neuffer et al., Reference Neuffer, Eicker, Eis, Holfelder, Jacobs, Yume and Konzeptwerk2020; Slimani et al., Reference Slimani, Lange and Håkansson2021). This tendency is at odds with educational practices geared towards political participation and empowerment, which are necessary for negotiating social-ecological transformation within planetary boundaries.

In this article, we aim to contribute to the conceptual and practical “re-politicisation” (Blühdorn & Deflorian, Reference Blühdorn and Deflorian2021) of ESD. For this, we used the conceptual framework of “prefigurative politics” (Raekstad & Gradin, Reference Raekstad and Gradin2020) in which we situate our participatory photovoice research with children and adolescents regarding the transformation of local food systems in Graz, Austria. Prefigurative politics describe practices of change in which (sustainable) counter-futures are examined and tested in the (unsustainable) present (Jeffrey & Dyson, Reference Jeffrey and Dyson2021, p. 641). We understand photovoice as a way of guiding this exploratory process in educational contexts. According to this view, the core concern of photovoice in ESD is to create power-critical spaces of possible futures in which students, as co-researchers, can question (un)sustainable hegemony, critically reflect on collectively internalised patterns of thought and action, and participate in the self-determined negotiation of liveable futures with the educational ambition of empowering students as political subjects (Pettig, Virchow, Schweizer, Halder & Neuburger Reference Pettig, Virchow, Schweizer, Halder and Neuburger2021).

In the following, we critically discuss ESD as an apolitical practice and identify starting points for its re-politicisation, subsequently reflecting on prefigurative politics as a participatory educational framework focusing on its potential to engage learners with a sense of place, create a sense of hope, and foster transformative experiences; we then further investigate these three dimensions using examples from our own participatory research practice.

Recentring the political in ESD

In 1987, the Our Common Future report formulated sustainable development as a guiding principle for the global society; defined it in terms of the three dimensions of ecology, the economy, and society; and established its interplay as a goal to tackle the sustainability crisis. Since the Earth Summit conference in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, the concept has become deeply embedded in education policy programmes and has been widely received and anchored in school and university curricula. However, the combination of “sustainability” with “development” has also been discussed critically from the outset (Kopnina, Reference Kopnina2014). Part of this critique is that ESD is placed in the service of a political top-down agenda for sustainability and education. As has already been demonstrated by several studies, this often serves as a specific idea of a sustainable future that follows a narrative of ecological modernisation (Euler, Reference Euler2022). As a result, ESD is broadly geared teleologically towards a specific sustainable future (that can be realised through technological advances), whereas other future narratives, alternatives, and utopias are often disregarded.

Hursh et al. (Reference Hursh, Henderson and Greenwood2015, p. 299) pointed out in this context that “environmental education is political.” They elaborated that, first and most obviously, there is a controversial debate on how to conceptualise and carry out environmental education. Second — and less obvious — political and economic thought and the logic of Western societies (namely neoliberalism) have become deeply embedded into environmental education and unconsciously shape its praxis. This Eurocentric perspective on sustainable development ignores non-Western value systems and remains rooted in an anthropocentric, dualistic worldview (Stein et al., Reference Stein, Andreotti, Suša, Cash and Čajková2020). Hursh et al. (Reference Hursh, Henderson and Greenwood2015, p. 301) further argued that “neoliberal political and economic policies not only undermine our ability to respond to current economic and environmental crises, but are, in fact, the primary cause of them.” Following the belief that neoliberal ideology underlies the predominant ESD praxis and can simultaneously be held accountable for current crises, ESD must be questioned as an affirmative praxis that keeps the status quo in place, rather than actually fostering systemic transformation (Selby & Kagawa, Reference Selby and Kagawa2010; Huckle & Wals, Reference Huckle and Wals2015; Euler, Reference Euler2022), a tendency that Kopnina and Bedford (Reference Kopnina and Bedford2024) labelled as “pseudo sustainability education.” ESD does this by universalising the demand for sustainability whereby equal human subjects are assumed, and the unequal distribution of responsibility, agency, and motivation is neglected, and by designating sustainability or sustainable development as the guiding principle of a “global society” (Stimm & Müller, Reference Stimm and Müller2023, p. 24).

Critical sustainability research shows that in this form of sustainable development, responsibility for sustainability is placed on individuals, and it is assumed that sustainability can be achieved primarily through behavioural change and modifications of consumption practices; ESD is viewed as a governmental practice that maintains power in place (Neuffer et al., Reference Neuffer, Eicker, Eis, Holfelder, Jacobs, Yume and Konzeptwerk2020), essentially sustaining the unsustainable (Blühdorn, Reference Blühdorn, Gabrielson, Hall, Meyer and Schlossberg2016). However, if it is only about training citizens to live a “green” lifestyle and adopting sustainable behaviours, the discussion on sustainability is de-politicised. That is, the individualisation and responsibilisation of sustainability consequently lead to an apolitical sustainability debate by addressing subjects solely as consumers within an unquestionable (neoliberal) system (Kehren, Reference Kehren2017). Therefore, the political is reduced to the personal (Hursh et al., Reference Hursh, Henderson and Greenwood2015, p. 309), thereby ultimately limiting it to behavioural change prescribed from “above.” This is also connected to the prevailing idea that “the political” is something done by “the politicians,” i.e. the elected representatives in charge of things and who have the power to change things (or not).

What is missing then are transformative forms of pedagogy, “addressing root causes of climate change, undermining the resilience of unsustainable systems and practices, decolonising knowledge, developing disruptive competence” (Selby & Kagawa, Reference Selby and Kagawa2018, p. 305–306) and engaging different actors in the process. To us, these forms of pedagogy have the potential to help re-politicise ESD by understanding the personal as political without disconnecting it from policymaking, thus potentially sparking social change through engagement and participation. “Sustainability” is then understood as a process that involves individuals, society, and politics; it is also seen as a subject of political negotiation in everyday life. Moving away from the affirmative practices of mainstream ESD aimed at maintaining the status quo through green growth, adaptation, and resilience in the sense of sustainable development (e.g. Ammoneit & Reudenbach, Reference Ammoneit and Reudenbach2024), the guiding value of social-ecological transformation in the context of ESD is more about enabling people to uncover and disrupt existing systems, practices, and routines in order to uncover and alter the causes of the unsustainable status quo. Lotz-Sisitka et al. (Reference Lotz-Sisitka, Wals, Kronlid and McGarry2015, p. 74) remarked:

In order to transform for the sustainability turn or transition, people everywhere will need to learn how to cross disciplinary boundaries, expand epistemological horizons, transgress stubborn research and education routines and hegemonic powers, and transcend mono-cultural practices in order to create new forms of human activity and new social systems that are more sustainable and socially just.

Following this understanding, recentring the political in ESD means (a) reflecting on the implicit agendas embedded in sustainable development and ESD; (b) understanding ESD as an open process, not the teleological realisation of a fixed sustainable utopia; and (c) making the interweaving of the social and ecological dimensions of climate change the starting point of all educational endeavours (i.e. addressing environmental matters as justice issues). Consequently, re-politicising ESD also means involving students in the negotiation of liveable futures by transgressing ingrained routines and the taken-for-granted (Lotz-Sisitka et al., Reference Lotz-Sisitka, Wals, Kronlid and McGarry2015), engaging in the processuality of transformation (Pettig & Ohl, Reference Pettig, Ohl, Solari and Schrüfer2023), creating possibilities through transformative experiments (i.e. enabling lived experiences of possible futures), exploring what could be, and deeply reflecting on these experiences for our everyday lives and praxis to shape liveable futures (Pettig, Reference Pettig2021).

In all of this, the political in ESD emerges “as the sphere of agonistic dispute and struggle over the environments we wish to inhabit and on how to produce them” (Swyngedouw, Reference Swyngedouw, D’Alisa, Demaria and Kallis2015, p. 90). This approach is based on the concept of politics, which is anchored in people’s everyday lives and perceives negotiation as an object of agonistic practice (Mouffe, Reference Mouffe2013). Thus, it is neither about responsibilisation nor about the abdication of responsibility; instead, we argue for the consistent intertwining of the personal and public spheres of political negotiation in search of liveable futures for all.

Prefigurative politics as an educational framework

In the next section, we explore the concept of prefigurative politics as a means of reorienting educational praxis within ESD. With its focus on “prefiguring” alternative futures and linking “the particular, local and present moment to alternative worlds and the future via imagination and practice” (Yates, Reference Yates2021, p. 1041), it engages the individual in a dialogue between the present and the future, interlaces personal and public politics, and manages to open a space that embraces the complexities of individual action and institutional politics.

While prefigurative politics has recently gained popularity within academia with the onset of the Occupy movements in the 2010s (Beckwith et al., Reference Beckwith, Bliuc and Best2016), the concept has a long history and was first used in 1965 by French anarchist Daniel Guérin in his work L’Anarchisme; it was later used to discuss revolutionary leftist strategy. Within this context, Boggs (Reference Boggs1977) examined prefigurative politics as an alternative to the main left-wing strategy of taking state power (Yates, Reference Yates2021, p. 1037). It was subsequently discussed as an overall leftist strategy that should be implemented mainly by parties, local governments, and social movements. Over the span of 60 years its usage has, however, changed and while it came to be viewed as an underpinning of strategic collective action in the “new social movement” in the 1990s, it was later used to understand ways of engaging rather than collective engagement (which brought new attention to, for example, practices of food or cultural politics). In recent decades, the concept has seen a vast uptake by disciplines outside of research on social movements (ibid. pp. 1038–1039).

Accordingly, the concept is often used more broadly to describe a shift in politics that uses an anti-authoritarian and participatory style of organisation and aims. We hence understand the term as referring to “a political orientation towards action” (ibid., p. 1041) that focuses on “the deliberate experimental implementation of desired future social relations and practices in the here-and-now” (Raekstad & Gradin, Reference Raekstad and Gradin2020. p.10). Prefigurative politics, therefore, includes a range of phenomena from the global Occupy movement in which activists criticised global social and economic inequalities and challenged them by “directly intervening in the ongoing reproduction of institutions at the local level, such as by enacting horizontal decision-making” (Reinecke, Reference Reinecke2018, p. 1300) to ecovillages around the world in which people create alternative practices of production and consumption in everyday life (Casey et al., Reference Casey, Lichrou and O’Malley2020). Other forms of prefigurative politics include street closures to motor traffic, which allow bicycle activists to enact a desired future of sustainable mobility (Cox, Reference Cox2023), or children playing freely in public urban spaces, thereby paving “the way toward the possibility of a more playful, child-friendly city” (Carroll et al., Reference Carroll, Calder-Dawe, Witten and Asiasiga2019, p. 297).

Geographers Jeffrey & Dyson (Reference Jeffrey and Dyson2021, p. 643) perceived the concept as being concerned with people “performing now their vision of a ‘better world’ to come” and referring to “strategies and practices employed by political activists to build alternative futures in the present and to effect political change by not reproducing the social structures that activists oppose” (Fians, Reference Fians and Stein2022). As such, it is fundamentally different from revolutions as it dwells on micropolitics rather than macropolitical change (ibid.):

Reimagining society locally may not bring about immediate large-scale changes, but it models the society one seeks to build, thus informing its participants’ practices and ways of thinking beyond local activist settings (ibid.).

Here, we focus on the interplay of a prefigurative tradition, activist theory, and critical pedagogy (DeLeon, Reference DeLeon2006; Mueller, Reference Mueller and Haworth2012; Kester et al., Reference Kester, Seo and Gerstner2023) and emphasise the conceptual value of prefigurative politics for educational practice in the Freirean tradition (Bolin, Reference Bolin2017). Hence, we view prefigurative action and reflection as innate educational experiences that strengthen students as political subjects in a critical and transformative process (see also Freire, 1970). Therefore, we propose three key dimensions of prefigurative politics that have explicit educational relevance for critical ESD and geography education: (1) engagement with a sense of place; (2) the potential to create a sense of hope; and (3) the potential to foster transformative learning and spark societal change. In the following section, we discuss each of these dimensions and their connections to prefigurative politics.

Engaging with everyday places

Prefigurative politics involve spatially situated practices (Sörensen, Reference Sörensen2023, p. 10; Cooper, 2016, p. 335) that can change locations through social experimentation (Asara & Kallis, Reference Asara and Kallis2023, p.72); examples include the Occupy movement in Puerta del Sol (ibid. p. 57) or humanitarian assistance provided during the 2015 migration movement (Sutter, Reference Sutter2020). These spaces can emerge in different forms such as “counter-spaces” (Asara & Kallis, Reference Asara and Kallis2023, p. 58) in which inventive capacities can unfold or spaces in which encounters become possible and where new kinds of relationships are developed, participation is made possible, and marginalised people are given access to resources (Sutter, Reference Sutter2020). Prefigurative politics thus lead to the production of political spaces that are constantly evolving and “in tension between the present and future, between the actual and the possible” (Ince, Reference Ince2012, p. 1653). The inherent spatiality of prefiguratism enriches ESD through involvement with the geographic concepts of place, space, and scale; moreover, it produces “comparisons, similarities, and contrasts within and between localities that provide for education that engages more easily with learners’ every life experiences” (Meadows, Reference Meadows2020, 89). Israel (Reference Israel2012) concluded that such a place-based approach in education challenges the disconnection of schools and classrooms from their social-ecological contexts and aims to transform both students and places through participation to promote a more just world through critical education.

Creating a sense of hope

Current environmental challenges are often met with negative emotions that have been described as “eco-anxiety” (Pihkala, Reference Pihkala2020), “negative earth emotions” (Albrecht, Reference Albrecht2019) or “environmental melancholia” (Lertzman, Reference Lertzman2015). These can partially be understood as expressions of “post-political depression” (Amsler, Reference Amsler and Dinerstein2016, p. 21) in which political responses (such as direct action or critical analysis) are often no longer seen as effective (ibid.). Many people and most adolescents live without hope that the future will be different and that they could play a role in changing and creating a different future (Holfelder, Reference Holfelder2019). Living in such a state means living in a world where possibilities are diminished or foreclosed (Amsler, Reference Amsler2015, p. 56). Using Amsler (ibid.), we argue that “possibility is political” and we understand prefigurative politics as a practice that challenges this foreclosure of possibility (ibid. 74). This practice encourages people “to hope again, hope differently, and transform formal hope into embodied practices of possibility” (ibid., pp. 19–20) or what Darren Webb referred to as transformative hope, which has a critical view of the present and is driven by the idea of a better future (Webb, Reference Webb2013, p. 409). Like other emotions, hope has long been omitted from ESD discourse (Kelsey, Reference Kelsey2016, p. 25) and is increasingly discussed within ESD (e.g. Ojala, Reference Ojala2012; Vandaele & Stålhammar, Reference Vandaele and Stålhammar2022). Likewise, critical geography education stresses creating spaces to address students’ grief and hope (Lopez, Reference Lopez2023, p. 794). Considering these ambitions, a prefigurative paradigm constitutes a contribution to pedagogies of hope and a possible pathway “for affective engagement toward imagining worlds otherwise” (ibid.).

Fostering transformation

Centred around the idea of decentralised self-organisation (Monticelli, Reference Monticelli2021, p. 106) and “embodying a different type of society within the old one” (ibid., p. 107), prefigurative politics challenge current societal structures and aim to create different forms of societal organisation. At the core, prefigurative politics require the organisational means of the present to be appropriate for a vision of how a future society should function (Raekstad & Gradin, Reference Raekstad and Gradin2020, p. 70). The process of creating an image of what society should look like and the establishment of counterinstitutions at least partially reshapes a person’s subjectivity (Sörensen, Reference Sörensen2023, p. 25). This reshaping of subjectivity can be regarded as emancipation of the self and can occur through three processes facilitated by the enactment of a desired future: (a) empowerment; (b) the drive to change; and (c) consciousness-raising (Raekstad & Gradin, Reference Raekstad and Gradin2020, pp. 71–78). Empowerment prepares people to live in a new society by “participating in activities and practices that are themselves egalitarian, empowering, and therefore transformative” (Ackelsberg, Reference Ackelsberg2005, p. 53, cited in Raekstad & Gradin, Reference Raekstad and Gradin2020, p. 71). Simultaneously, the experience of prefigurative actions changes people’s needs, goals and desires (ibid., p. 73) and helps them develop a revolutionary awareness (ibid., p. 74). In this view, prefigurative politics is a social process that involves people in transformative experiences that may result in manifold learning outcomes in the context of social-ecological issues and concerns while intertwining individual and societal learning. Such outcomes are “the shared construction of new knowledge, practical skills and understanding; a sense of unity and interconnectedness; changes in worldview and identity; a sense of agency and empowerment; critical systemic and complex thinking; and social learning” (Formenti & Hoggan, Reference Formenti and Hoggan-Kloubert2023, p. 112 based on Rodríguez Aboytes & Barth, Reference Rodríguez Aboytes and Barth2020). Furthermore, social learning comprises the “reinforcement of social relationships, social mobilisation and activism” (Rodríguez Aboytes & Barth, Reference Rodríguez Aboytes and Barth2020, p. 1001). Consequently, integrating a prefigurative paradigm into ESD embraces transformative experiences beyond formal settings in their value for institutionalised educational contexts by integrating everyday practices and experiences into classroom discourse, allowing people to make meaning together through experimentation, dialogue and deep reflection to foster transformative learning (Pettig, Reference Pettig2021).

In sum, the three elements of prefigurative politics discussed here resonate with educational ideas currently being explored within critical ESD discourse. Re-politicising ESD through a prefigurative approach urges us to implement teaching methods that allow students to experience and reflect on the tensions of personal and public politics, engage students with places of everyday life, foster a sense of hope among learners, and spark transformative experiences that lead to personal and societal transformation.

The prefigurative potential of participatory photovoice research

In the following, we illustrate how photovoice, a method of participatory action research (PAR) based on political-educational values grounded in the liberation pedagogical thinking of Paulo Freire (Reference Freire1970/2005), can be understood as a method that can challenge “teachers and students to empower themselves for social change, to advance democracy and equality as they advance their literacy and knowledge” (Shor, Reference Shor, McLaren and Leonard1993, p. 24) in a prefigurative tradition and recentre the political in ESD in the (geography) classroom. The prefigurative potential of PAR was emphasised over two decades ago (Kagan & Burton, Reference Kagan and Burton2000) and has been further explored in sustainability transition research (Silonsaari, Reference Silonsaari2024) and ESD (Ojala, Reference Ojala2022; Trott et al., Reference Trott, Weinberg and Sample McMeeking2018; Trott, Reference Trott2019). We aim to build on this understanding and focus on its implications for educational practices.

Photovoice was first introduced by Wang and Burris (Reference Wang and Burris1997). It is inspired by Paulo Freire’s problem-posing education, feminism, and documentary photography (ibid., pp. 172–177) and enables participants to present their perspectives through photos, discuss them publicly with stakeholders, and work towards change within their communities (ibid.). In photovoice studies, participants act as “co-researchers” (von Unger, Reference Von Unger2014) and are involved in different steps of the research process. Photovoice thus combines a visual research technique with critical dialogue with the goal of improving the lives and life worlds of co-researchers (Sutton-Brown, Reference Sutton-Brown2014, p. 170). In this sense, photovoice follows an emancipatory and transformative research ideal and is always related to desirable futures, imagination, and negotiation (Farrales et al., Reference Farrales, Hoogeveen, Sloan Morgan, de Leeuw and Parkes2022).

As part of an interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary research project on (un-)sustainable food systems initiated through cooperation between geography education and human geography at the University of Graz, we conducted participatory photovoice research with over 100 children and adolescents (10–14-year-olds) from three secondary schools in Graz, Austria. In this project, we addressed barriers to sustainable food consumption and supply, identified potential changes in local communities, explored current food practices and desirable food futures, and discussed potential starting points for change with public and local decision-makers (such as school management, teachers, politicians, and public officials). The photovoice process was adapted to the geography classroom to fulfil students’ and institutional needs (Pettig et al., Reference Pettig, Virchow, Schweizer, Halder and Neuburger2021) and was structured into three phases (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Participatory photovoice research overview (adapted from Pettig et al., Reference Pettig, Virchow, Schweizer, Halder and Neuburger2021, p. 20; Pettig et al., Reference Pettig, Lippe, Stöcklmayr, Ermann and Strüver2023, p. 6).

A blend of methods was used in the accompanying research, including focus groups, learning and research diaries, field notes and in-depth interviews. Here, we have used fragments of the collected data to exemplify the prefigurative potential of participatory photovoice research as a contribution to re-politicising ESD by reconstructing two research processes from different groups of co-researchers. The examples originate from two different schools.

Example 1: Bringing back the vending machine — How the school becomes a renegotiable place

At the beginning of their photovoice project in 2024, co-researchers Dominik, Murat, Ezra and Ahmed were unsure of what to focus on and struggled to identify a topic that a teacher suggested to them. In an attempt to find a topic they considered meaningful to their lives and in exchange with an academic researcher, they tentatively decided to focus on food-related issues at their school that they would like to improve.

By exploring their school grounds and during the ensuing reflections, each co-researcher identified an issue that was particularly important to them and which they later contributed to the exhibit, which showcased their ideas towards sustainable food practices at their school (see Figure 2). Murat emphasised the lack of outdoor seating opportunities for students during recess, while Ezra focused on the school kitchen’s cleanliness and the lack of effort some students put into cleaning, which then became the teacher’s task. Ahmed advocated for more awareness of the correct disposal of food waste, and Dominik advocated for a more varied selection of food and drinks in cafeterias and vending machines.

Figure 2. Photos taken by the co-researchers (Photos: Ezra, Murat, Dominik and Ahmed, 2024).

Over the course of their exploration, the co-researchers gained a new understanding of their relationship with their school. While initially showing little confidence that they could influence current food practices, arguing that new seating arrangements would be “too expensive” (3_Rt2_D, 31:05) or that they would get in trouble with school officials if they advocated for their ideas (3_Rt2_D, 47:20), they slowly gained confidence in presenting their ideas and created an interactive exhibit. They invited visitors to express their ideas for the school, thereby developing a sense of responsibility for the place. This renewed relationship with school as a place of everyday life is further reflected in the transformation of the exhibit’s title. While the initial title was “Our wishes for [name of the school],” it was changed to “Our wishes for our school” (memo from field notes, 2024). This process reflects photovoice’s inherent connection to place and its potential to engage co-researchers with familiar place(s) in new ways, providing insights into the connection between place and identity (McIntyre, Reference McIntyre2003). Due to their exploratory nature, co-researchers have developed and established new perspectives in their communities through photovoice research (e.g. Carpenter, Reference Carpenter2022). With Biglin (2021), this process can be further regarded as a political act of placemaking; while generating visual representations of co-researchers’ placemaking practices, their research also represents subtle political acts of placemaking and belonging; they hence (re)produced their school as a place.

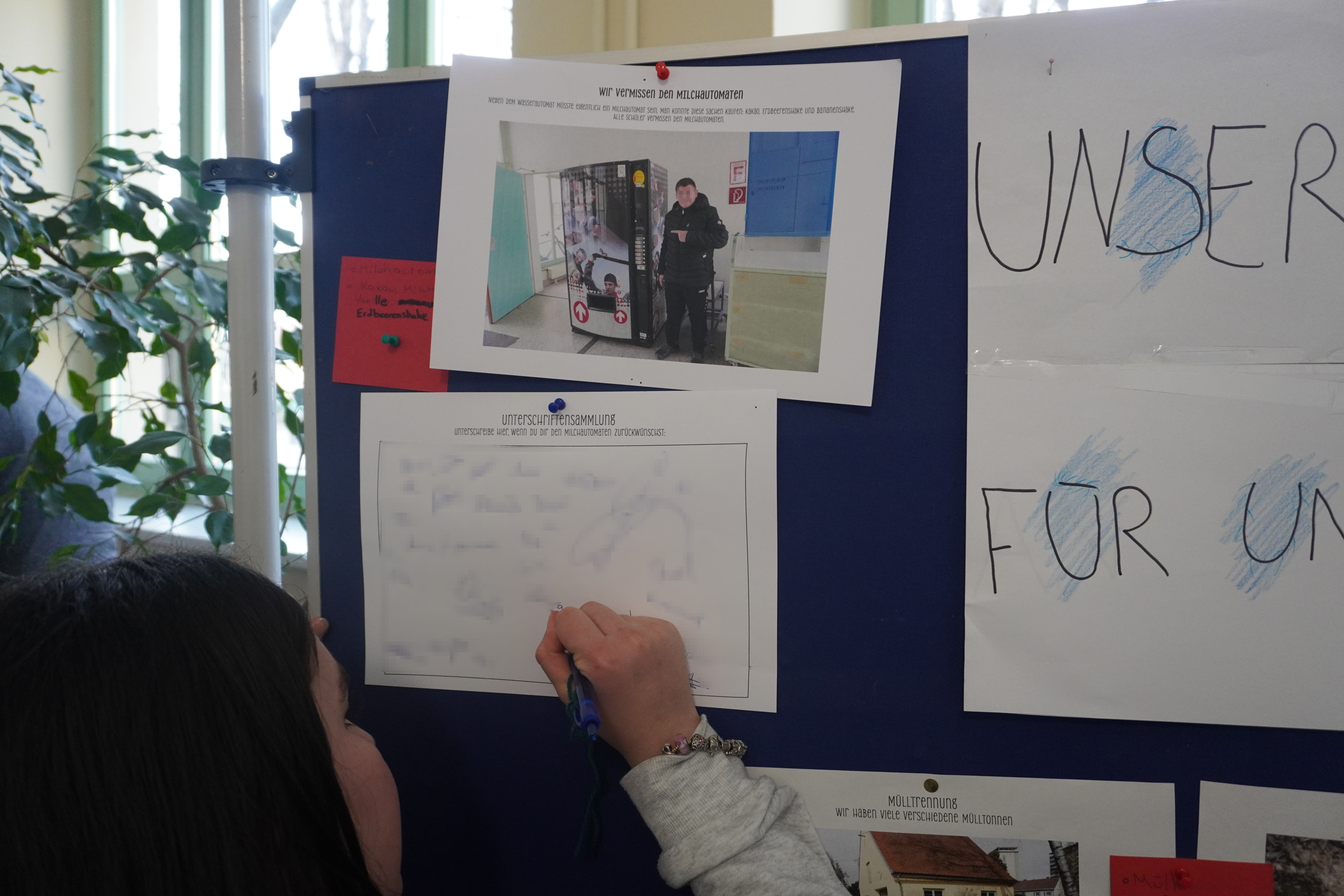

The effect these subtle political acts can have on the individual’s understanding of his/her role in negotiating the future can be understood when looking at Dominik, who included a petition (see Figure 3) for his “beloved” milkshake vending machine, which was replaced by one that only contained sparkling water with different flavours. In the process of advocating for this vending machine, Dominik cultivated hope that the group could play a role in bringing it back. In the beginning, he was unsure what to critique (3_Rt2_D, 40:25) and even feared the principal’s reaction to his ideas (3_Rt2_D, 41:50). However, during the reflection, he began to develop ideas for what was possible and thought about compromises such as advocating for “organic alternatives” (3Rt2_D, 44:35). At the end of the project, Dominik expressed his contentment with the fact that many people seemed to care about the vending machine and that many people signed the petition: “I am proud that there is a possibility that we [can] get it back” (3_Ft2_D, 57:37).

Figure 3. A student signing the petition set up by the research group (Photo: M. Taibinger, 2024).

The research process allowed students to identify issues, express their ideas, and renegotiate school politics towards sustainable food practices on a micro level. Questions arose such as who is in charge of the school as a place, what can be addressed by whom, and changes that accompany the students’ research process. This created a space in which neither the students nor the school administration ended up with the final responsibility, but one in which the politics of the school could be renegotiated and where the space itself became understood as one of possibility in which the co-researchers could act as agents of change, and the question of who is in charge of this place became renegotiable.

Example 2: Becoming a part of it — How co-researchers experience themselves anew

At the beginning of a photovoice project in early 2023, Efe mentioned in his research diary that he usually ate healthily and weighed ingredients (Efe, research diary, 2M1). At home, he would prepare something to eat in the morning and evening but would not eat anything at school (1_Ft1_K, 00:28:45). With regard to his own future and that of the planet, he articulated the concern “that food will become more expensive than it is now; or rather, even more expensive” (1_Ft1_K, 00:14:38). He was annoyed by the wasteful use of food at his school, because “some people don’t have any food and [some classmates] just throw it away” (1_Ft1_K, 00:33:01). He also addressed the high cost of sustainable food, “because everything is very expensive in the organic food market” (1_Ft1_K, 00:37:45). Efe’s reflections touch upon urgent questions and issues of food equity and justice in the context of food system transitions (Ambikapathi et al., Reference Ambikapathi, Schneider, Davis, Herrero, Winters and Fanzo2022).

During the project, Efe found himself in a group of co-researchers who were working on their research in a rather listless and disinterested manner, partially because they were unsure what question they were “expected to do research on” by teachers and academic researchers (field notes and exchanges with accompanying teachers, 2023). When the group’s research reached a standstill, the student co-researchers conversed with us as academic scholars. Here, Efe stated that the overarching theme of the photovoice project, sustainable food consumption, had nothing to do with him and his working group: “This is a topic for rich Austrians, not for people like us” (memo from field notes, 2023). Efe expressed that he experienced himself as part of a marginalised group excluded from the discourse on sustainable food systems. To a certain extent, this can be interpreted as the internalisation of the dominant neoliberal reduction of the politics of sustainability to the personal, linking it to economic status and thus reducing it to a luxury good for responsible consumers (Swyngedouw, Reference Swyngedouw, Hillier and Healey2010).

This irritation sparked a conversation about the group’s questions and concerns, which resulted in a new focus for their research on the question of whether it is possible to supply oneself with healthy, sustainable, and affordable food on-the-go in their local communities. The affordability of food as well as the fair distribution of, and access to, healthy and sustainable food were implicit but unspoken topics for Efe and his group from the very beginning (see the previous section on Efe’s point of view or see Figure 4, a photo taken before this reorientation of the research), but only became visible and explicit from the irritation towards the overarching theme of participatory photovoice research. At this point, the co-researchers appropriated the overarching theme and made sustainable food consumption their topic, effectively demanding a say in its micropolitical negotiations within their local communities in a prefigurative manner.

Figure 4. Sustainable but expensive to-go food in local supermarkets (Photo: Efe, 2023).

As part of their research, the co-researchers articulated that they were “looking for alternatives” (accompanying text to the exhibit), envisioning a healthy, tasty and sustainable food supply for all in everyday life. Consequently, the group’s exhibit included several of their own recipes for sustainable school meals — partially reflecting their cultural heritage — that are easy to implement in everyday life and which also directly appealed to visitors (see Figure 5). The text accompanying the exhibit read, “You should be aware that you can save time and buy something healthy and affordable at the same time.”

Figure 5. Efe discussing his research findings on the affordability of healthy, sustainable food in his community with students, parents and school staff (Photo: E. Flucher, 2023).

In a debriefing on the photovoice project, Efe articulated that he was proud of his research team (1_Ft2_K, 00:18:15): “I think we have achieved a lot in our research. Many people have been made aware of this issue. I have seen that many people are interested in the fact that it is difficult to eat healthily and affordably when you are out and about due to the stress of everyday life” (1_Ft2_K, 00:14:57).

Over the course of the project, Efe experienced himself in a new role, personally tackling the public politics of sustainability and becoming part of the discourse on a sustainable food future. He was able to raise awareness of the problem of food equity in his community and helped make the issues of food equity and accessibility visible, sparking hopeful discussions on how food equity could become a reality in the future.

Conclusion

The success of a social-ecological transformation depends on whether paths to a sustainable future can be identified through collective efforts. In this context, educational programmes are needed that consistently focus on the political foundation of such a project and empower young people to participate in negotiations. Drawing on the analytical framework of prefigurative politics, this article shows that photovoice can make valuable contributions to the politicisation of sustainability issues in ESD. The participatory visual method can achieve this by creating spaces of possibility for the prefigurative negotiation of liveable futures, particularly because of its potential to bring learners into contact with everyday places and help them see these places anew, create a sense of hope by contributing to social-ecological transformation, and foster transformative learning experiences. In this context, it is vital to avoid instrumental appropriation of a political undertaking under a critical-transformative guise in the name of sustainability. In our experience, it is essential to continuously refocus on the interplay between the personal and public spheres of political negotiation within ESD practice in a prefigurative manner for this to become possible.

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial support

This research was supported by the Austrian Federal Ministry of Education, Science and Research with the program Sparkling Science, project SPSC_01_125-EAT+CHANGE. The authors acknowledge the financial support by the University of Graz.

Ethical standards

The participatory research project took place as a voluntary elective at the cooperating schools, and all co-researchers and their parents/guardians gave their verbal and written consent.

Author Biographies

Dr Fabian Pettig is an associate professor of geography education and economic education in the Department of Geography and Regional Science at the University of Graz, Austria. He has a dedicated interest in pedagogical questions and concerns on sustainability and geography education. His research revolves around educational-philosophical issues in environmental and sustainability education as well as transformative and participatory learning environments.

Daniela Lippe is a PhD student in the field of geography education and economic education in the Department of Geography and Regional Science at the University of Graz, Austria. She previously worked as a teacher after completing a teaching degree in geography and economic education. Her research interests include participatory research and the role of emotions within sustainability education.