Policy Significance Statement

This research underscores the urgent policy need of leveraging artificial intelligence (AI) to address women’s financial exclusion in Nigeria. With a widening gender gap and substantial poverty rates, Nigeria faces a critical need for innovative solutions. By providing the context on women’s financial exclusion, and highlighting key barriers and policy responses to these, the research underscores the potential of AI-powered fintech to break down barriers, lower costs, and personalize services for women. Policymakers should prioritise strategic interventions that harness AI, fostering economic empowerment and social inclusion. The research offers actionable insights, advocating for targeted policy choices to bridge the gender gaps in financial inclusion, aligning with SDG 5 on gender equality and broader goals of poverty alleviation, and inclusive economic growth.

1. Introduction

Globally, women represent a higher percentage of the financially excluded, with 56 percent of those without a bank account being women as of 2021 (Word Bank Group, 2022). However, the gender gap in financial inclusion in Nigeria is not only wider than other countries in Africa but also one of the widest in the world. In Nigeria, 31 percent of women have a formal account compared with 61 percent of men (EFInA, 2019). Recent statistics also indicate that Nigerian women are 12 percentage points less likely than men to be financially included, and the projections are that the gap will persist without interventions at industry, policy, and regulatory levels (WFID, 2022). With 87 million people living in extreme poverty, including 43.7 million women (Sasu, Reference Sasu2022), poverty also impedes national progress in financial inclusion.

Financial inclusion refers to individuals and businesses having access to affordable financial products and services that meet their needs, such as payments, savings, credit, insurance, and pension schemes (World Bank nd.; EFInA nd.). It plays a vital role in empowering women economically and socially, fostering their agency, well-being, and gender justice while fighting inequality and poverty (World Bank nd.). Financial technologies (Fintech) offer an opportunity to reduce women’s financial exclusion by leveraging automation and innovations like artificial intelligence (AI), big data, the Internet of things, and blockchain to create new financial products or enhance existing ones. AI-powered Fintech can lower costs, break entry barriers, personalize services, and provide diverse financial options for women. Despite past policy efforts, women’s financial inclusion remains a challenge, with limited research on how AI applications benefit Fintech in Africa (Ahmed, Reference Ahmed2021). This study seeks to understand AI’s current application and its potential to improve financial inclusion for women, using four indicators: licensed services, provider locations, AI use in products, and specific use cases applications. The critical question driving the research is, how can AI effectively address the challenges of women’s financial exclusion in Nigeria? The research leverages publicly available data for a qualitative analysis of AI-powered Fintech services, identifying inclusivity for women from the product design and target or potential users.

The Findings suggest that despite claims of AI-driven innovation, Fintech has not effectively targeted financially excluded women, and the extent of AI utilization is unclear. The article further highlights the challenges of exclusion and bias inherent in AI applications even if they are used and identifies policy approaches to minimise their negative impacts. The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 provides context on women’s financial exclusion by highlighting the key barriers to women’s financial inclusion in Nigeria, the policy responses to the barriers, and the potentials and risks of AI for women’s financial inclusion. Section 3 presents findings from the survey of Fintech services and their use of AI for women’s inclusion. Section 4 discusses and analyses the findings in the context of using AI to promote women’s financial inclusion. The paper concludes with policy strategies for inclusion and proposals for further research.

2. The state of gender financial inclusion in Nigeria

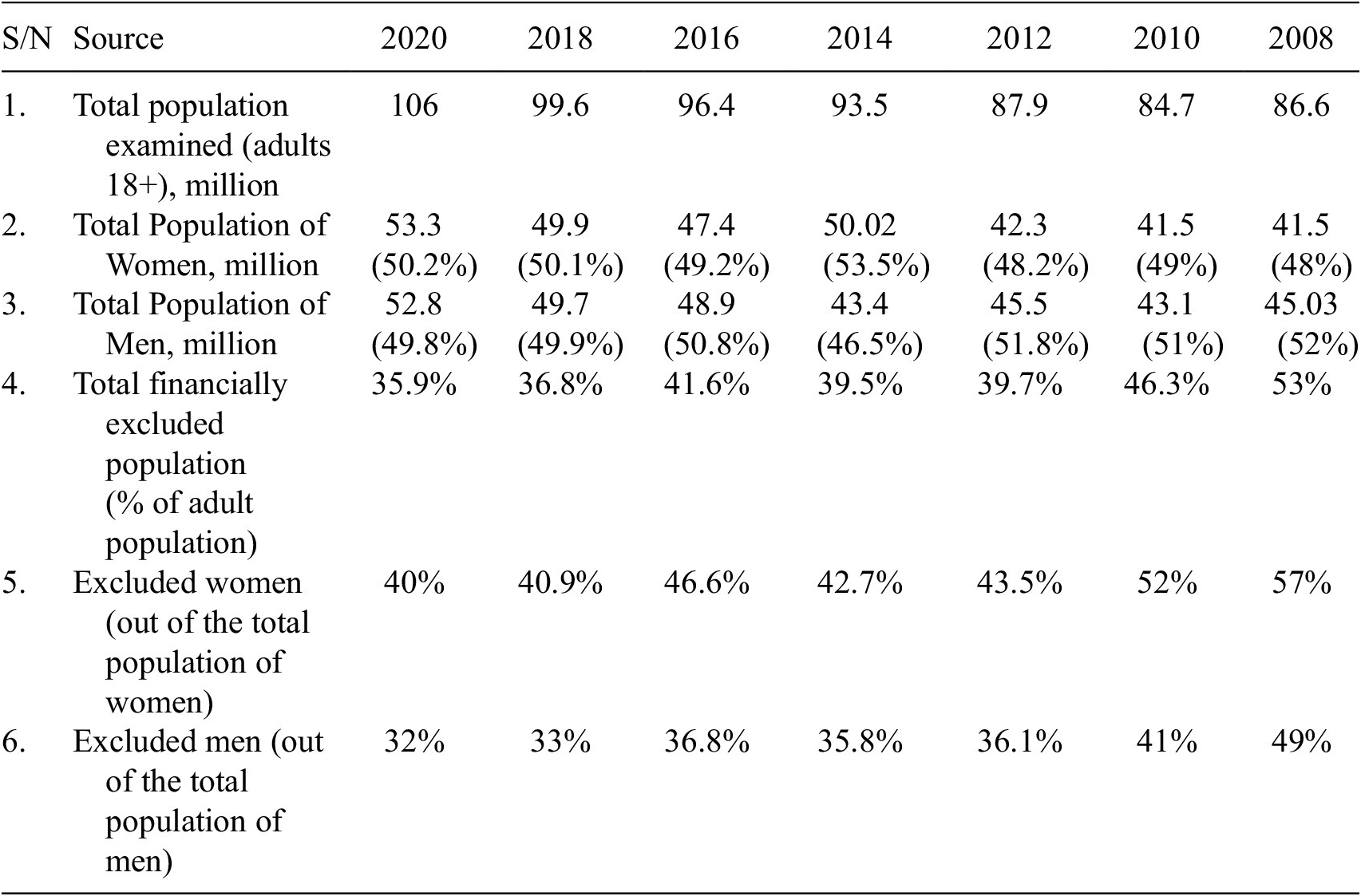

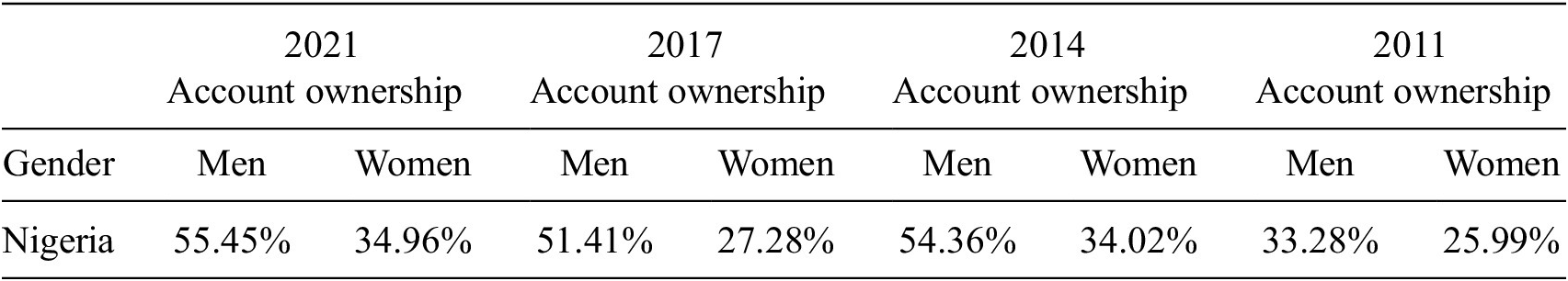

Data on financial inclusion collected over the years show that in Nigeria, men are more likely than women to own accounts and use formal sources for savings, credit, and remittances. Data derived from the surveys conducted by Enhancing Financial Innovation and Access (EFInA, 2021) and World Bank (aggregated in Tables 1 and 2) show the gender financial exclusion rates from 2008 to 2021.

Table 1. Financial exclusion rates from 2008 to 2020 (EFInA 2008 –2021)

Table 2. World Bank—data on gender based account ownership (Global Findex Database 2021)

Tables 1 and 2 are significant not only for elucidating lack of uniformity in the indicators for measuring financial inclusion but also the slow progress in women’s financial inclusion. The World Bank employs the sole parameter of account ownership as an indicator of financial inclusion, which has the advantage of presenting the stark reality of exclusion; account ownership is an essential and initial step in accessing financial services. However, the metrics also omit underserved groups and communities including those who own accounts without access to credit. EFInA (Table 1) adopts a broader spectrum of indicators, encompassing access to payment mechanisms, savings, insurance, credit, and pensions, which it measures by the percentage of the adult population engaging with these services at regulated institutions annually. Although, this approach aligns with current best practices reflected in the G20’s Global Partnership for Financial Inclusion (GPFI), which advocates for a tripartite measurement framework of access, usage, and service quality, the inference remains unchanged: there has been no significant shift in women’s financial exclusion rates since 2008. As par Table 1, almost 40 percent of the total population of 106 million (about 42 million) people are financially excluded in 2020 compared to 53 percent of 86.6 million (about 45million people) in 2008. Fifty-seven percent of 41.5 million (about 23.65 million) women were excluded in 2008 compared to 40 percent of 53.3 million (about 21.32 million) women in 2020. This represents a 9.87 percent reduction over a period of 12 years. The number of financially excluded women has held steady and risen consistently with the population, suggesting that policy approach to women’s (and indeed overall) financial inclusion may be ineffective or unsustainable. The analysis of key barriers and policy approaches in the next section foregrounds this assumption.

2.1. Key barriers to women’s financial inclusion

The key barriers to women’s financial inclusion are demand-related, supply related, technical and infrastructure related, and financial literacy and legal and policy-related barriers (Central Bank of Nigeria [CBN], 2020). Demand barriers stem from low income, lack of trust in formal financial services, and social norms (CBN, Reference Stumpf, Peters, Bardzell, Burnett, Busse, Cauchar and Churchill2020). It implies that women may prefer cash due to lower income and financial literacy levels as well as distance when bank branches are not available or proximate to their locations (CBN, Reference Stumpf, Peters, Bardzell, Burnett, Busse, Cauchar and Churchill2020). These barriers persist for digital financial services (DFS). Fewer women have completed fully digital payments and have digital IDs like the National Identity Numbers (NINs; CBN, Reference Stumpf, Peters, Bardzell, Burnett, Busse, Cauchar and Churchill2020). The NIN is a new requirement for meeting identification requirements including account opening in Nigeria. Not having the NIN therefore reduces the likelihood of owning an account or accessing the broader range of financial and public services. Supply barriers arise when existing services do not adequately meet women’s needs. Indicators include the absence of suitable financial products, unclear business cases for financial service providers, high costs in reaching women, and the lack of critical mass for digital payments (CBN, Reference Stumpf, Peters, Bardzell, Burnett, Busse, Cauchar and Churchill2020). Technical and infrastructure barriers encompass physical, network, and data infrastructure. For instance, women lag men in mobile phone ownership and internet access. A report indicates that in Nigeria, 56 percent of men use mobile internet, whereas only 34 percent of women do so—a notable gender gap of 38 percent (GSMA, 2022). In the context of financial inclusion, gender-disaggregated data are also a crucial (data) infrastructure which has been historically lacking (EIGE, nd).

The Financial literacy barrier is widely acknowledged as limiting women’s financial inclusion. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) defines financial literacy as “a combination of financial awareness, knowledge, skills, attitude and behaviours necessary to make sound financial decisions and ultimately achieve individual financial well-being” (OECD, 2012). Financial illiteracy among women is exacerbated by functional illiteracy (higher among women who traditionally lag men in access to formal education in Nigeria), low mobile phone ownership among women (which limits their social, digital, and financial inclusion), limited Internet access, and failure or inability to obtain official ID like the NIN. Legal and policy barriers manifest in a lack of, or ineffective policies (discussed below) on women’s financial inclusion. Other challenges, such as the gender pay gap and cultural practices can hinder women’s economic participation and exacerbate demand barriers, thus requiring legal intervention. A potential intervention could mandate the use of gender-disaggregated data in financial decision-making processes. Although policy already requires the collection of this data, research indicates that it is not yet utilized for strategic decisions aimed at enhancing financial inclusion (WFID, 2022).

2.2. Policy responses

The statistics on financial inclusion in Tables 1 and 2 are an indictment of past and extant policies to accelerate gender financial inclusion and gender equality broadly. The first National Financial Strategy developed in 2010, was revised in 2018 partly because it failed to meet the target of increasing financial inclusion across all indicated groups including women (CBN, 2018). Perhaps, recognising this shortcoming, the CBN established a Framework for Advancing Women’s Financial Inclusion in Nigeria in Reference Stumpf, Peters, Bardzell, Burnett, Busse, Cauchar and Churchill2020. The framework contains eight strategic imperatives to spur financial inclusion among women (CBN, Reference Stumpf, Peters, Bardzell, Burnett, Busse, Cauchar and Churchill2020). The critical strategic imperatives include the expansion of the financial and digital literacy capabilities and skills programs for low-income women in the context of specific financial behaviours and products, and the expansion of delivery channels to serve women customers close to home (CBN, Reference Stumpf, Peters, Bardzell, Burnett, Busse, Cauchar and Churchill2020). Also, in July 2022, the CBN released the Exposure Draft on Digital Financial Services Awareness (CBN, 2022a). The objectives of the Guidelines include addressing gaps in consumer knowledge and financial products development, setting digital literacy standards, and integrating financial literacy into existing financial education programmes (CBN, 2022a, Clauses 1.1 and 1.2). In January 2021, the CBN rolled out a Framework for Regulatory Sandbox Operations. The Sandbox is a formal process for firms to conduct live tests of new, innovative products, services, delivery channels, or business models in a controlled environment, with regulatory oversight, subject to appropriate conditions and safeguards (CBN, 2021a). Its objectives include increasing the potential for innovative business models that advance financial inclusion and ensuring appropriate consumer protection safeguards in innovative products (CBN, 2021a, Clause 1.1). In November 2022, a broader policy approach in the form of a National Fintech Strategy (NFS) was published. The purpose of the NFS is to set an agenda for inclusive fintech that enhances and deepens access to the use of fintech by 2024 (CBN, 2022b). In addition to the policy frameworks, the CBN has disparate and overlapping guidelines for DFS in Nigeria (CBN, 2023, 2021b).

The specific causes of policy inefficiency are not well-documented as agencies like the CBN rarely release progress reports that could elucidate such challenges. This calls for a deeper examination of AI, its potential, and its risks, prior to formulating policies for its deployment in finance or other sectors.

2.3. AI capabilities and risks

Fintech already contributes to the growth of mobile network operators that offer basic financial services in local communities, customer education, and ease of transactions (Kola-Oyeneyin et al., Reference Kola-Oyeneyin, Kuyoro and Olanrewaju2020). Nevertheless, some barriers to women’s financial inclusion persist. Relative to traditional banking, fintech requires advanced financial literacy skills. Points of sale services, often touted as having the capacity to bridge the rural/urban divide in financial inclusion, also require users to be physically present at service kiosks, recreating problems associated with distance from bank branches or financial service points. Service and transaction charges such as ATM transaction fees, or minimum account balances reinvent the challenges of cost and affordability for poor people at the grassroot and rural communities (CBN, 2018). Also, many DFS services require documentation and identification processes as part of Know Your Customer (KYC) and Anti-Money Laundering (AML) regulations, (CBN, 2018) which perpetuate entry barriers for those without required identification like NIN. Furthermore, women are underrepresented in the fintech user base in Nigeria. Statistics indicate a gender gap of 9.6% already exists in DFS, with only 13% of the female population completing a fully digital payment compared to 22.6% of the male population CBN, Reference Stumpf, Peters, Bardzell, Burnett, Busse, Cauchar and Churchill2020). AI can be used to minimise these problems. The broad range of AI-powered applications, products and services facilitate transactions, customer services, assets and risk management, fraud detection, financial advice and credit scoring and decision-making. For excluded demographics like women, AI can provide insights into consumer needs and allow providers to customise and personalise financial services. For example, credit scoring algorithms can facilitate access to credit and eliminate credit scoring biases by generating alternative data streams, such as digital footprints for financial decision-making (WEF, 2022). These can unlock insights into data and enhance the creditworthiness of women who have limited credit history. Using voice and face recognition and natural language processing, AI can aid identification and verification of users without official identification. Promising development in voice and speech recognition algorithms, including text-to-image and text-to-video applications, can aid the development of applications that allow people with low literacy to participate in the digital economy (WEF, 2022; Feingold, Reference Feingold2022). Overall, AI can lower the entry threshold (demand related harriers) that has traditionally hindered women’s access to financial services and enhance the quality and diversity of services offered to them, thus addressing supply related barriers.

This is not to suggest that AI is the silver bullet for financial inclusion. Indeed, the application of AI in finance poses significant risks such as bias and disparate impact of credit outcomes, which may stem from inaccurate, non-representative and low-quality data (OECD, 2021). Specifically, machine learning (ML) models in decision-making raise concerns around transparency, accountability, and equity. Nigerian women, who are under-represented in financial datasets due to historical financial exclusion, may find these ML models to be biased, as they often reflect and perpetuate the prejudices present within the data. Consequently, these systems may favour historically privileged groups like men (Women’s World Banking, 2021).

Furthermore, service providers do not appear to be innovating to the needs of financially excluded women (EFInA, 2020). One study, perhaps the only one so far in Africa, found that less than one percent of fintech providers use AI and only for business-to-business tech support purposes that increase operational efficiencies (Ahmed, Reference Ahmed2021). Such use cases include conversational AI and robotic process automation systems for repetitive business processes associated with AML, countering terrorist financing (AML/CTF) and KYC operations. This suggests that the primary use of AI in these contexts is to streamline business operations, not to meet the financial service needs of women who are excluded from the financial system.

The data and analysis in the next section builds on this premise. Since AI application in finance is relatively new, we assume that existing research and explanations may not fully capture the complexities of the AI ecosystem and the behaviour of different players. The research uses four indicators to assess whether and how AI might improve women’s financial inclusion. The indicators are types of licensed services, location and geographical spread of service providers, percentage of service providers using AI in Nigeria and the respective use cases. The objective is to draw inferences from the data about the present use and challenges of designing and deploying AI for women’s financial inclusion.

3. Results

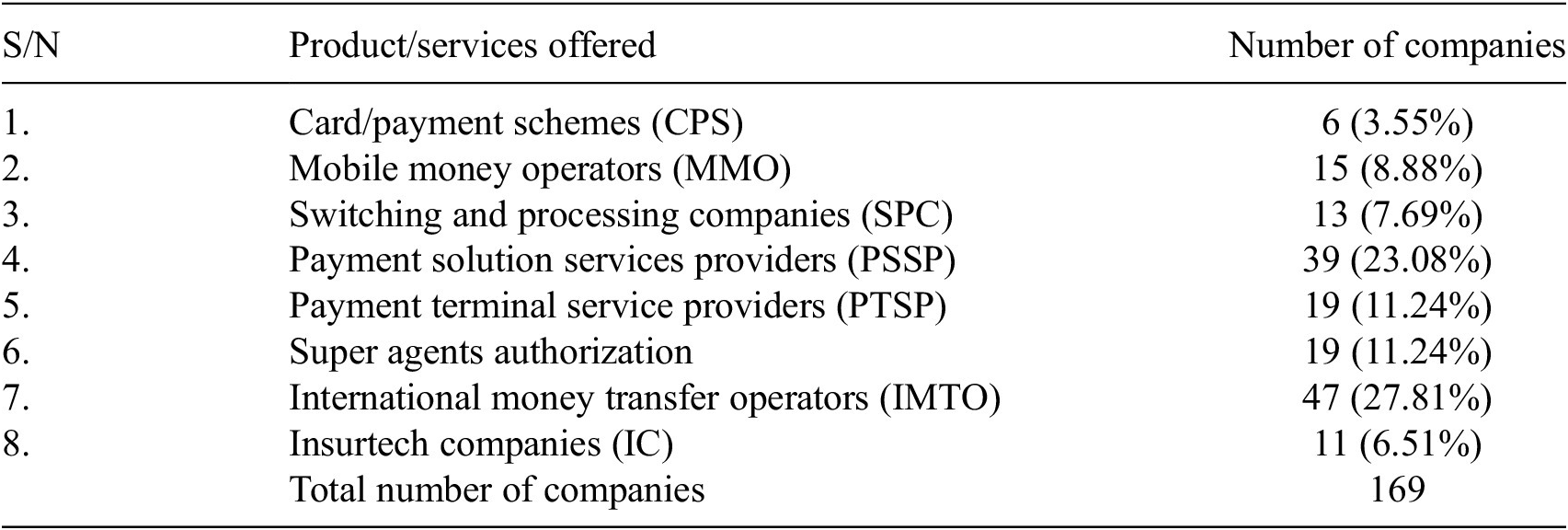

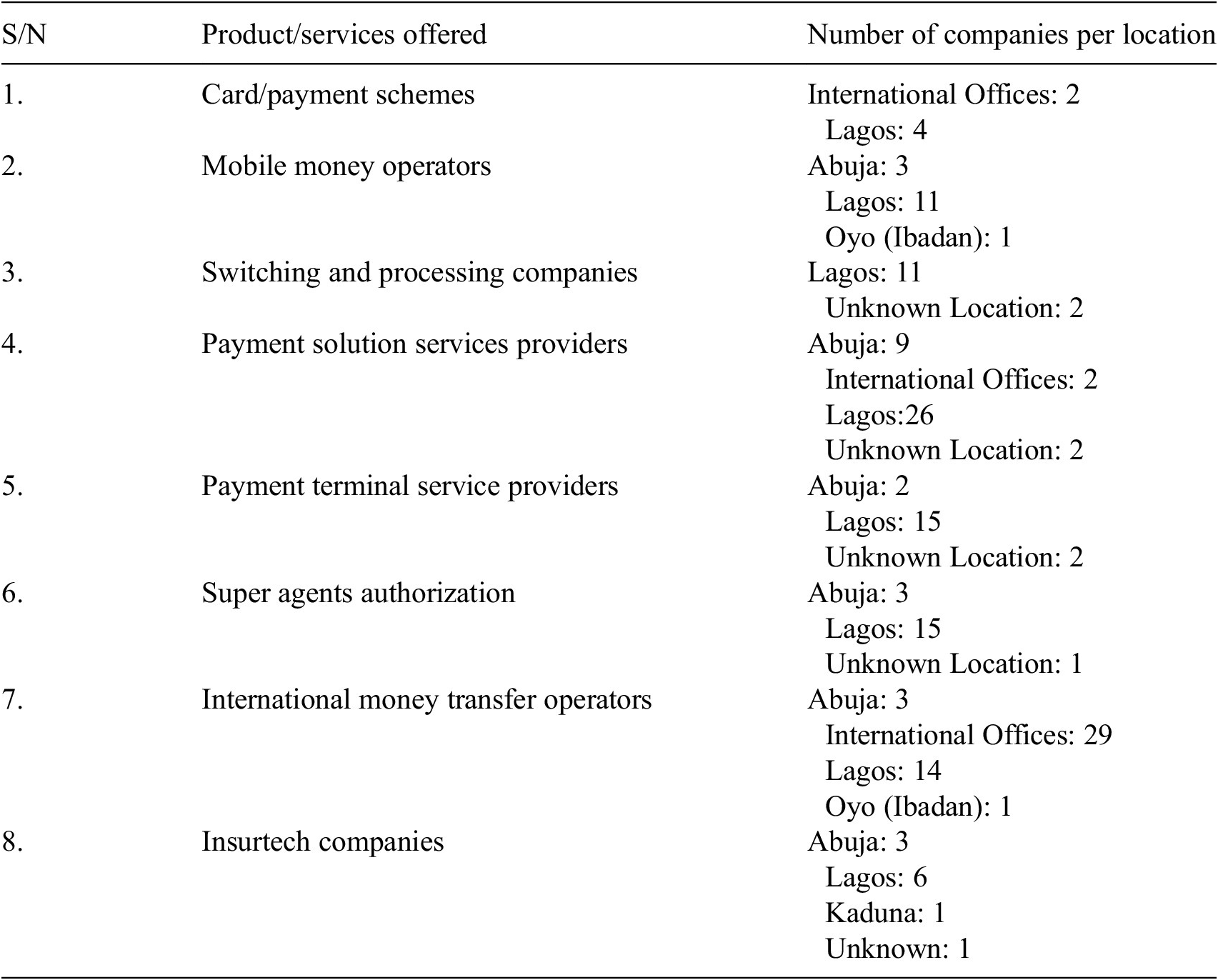

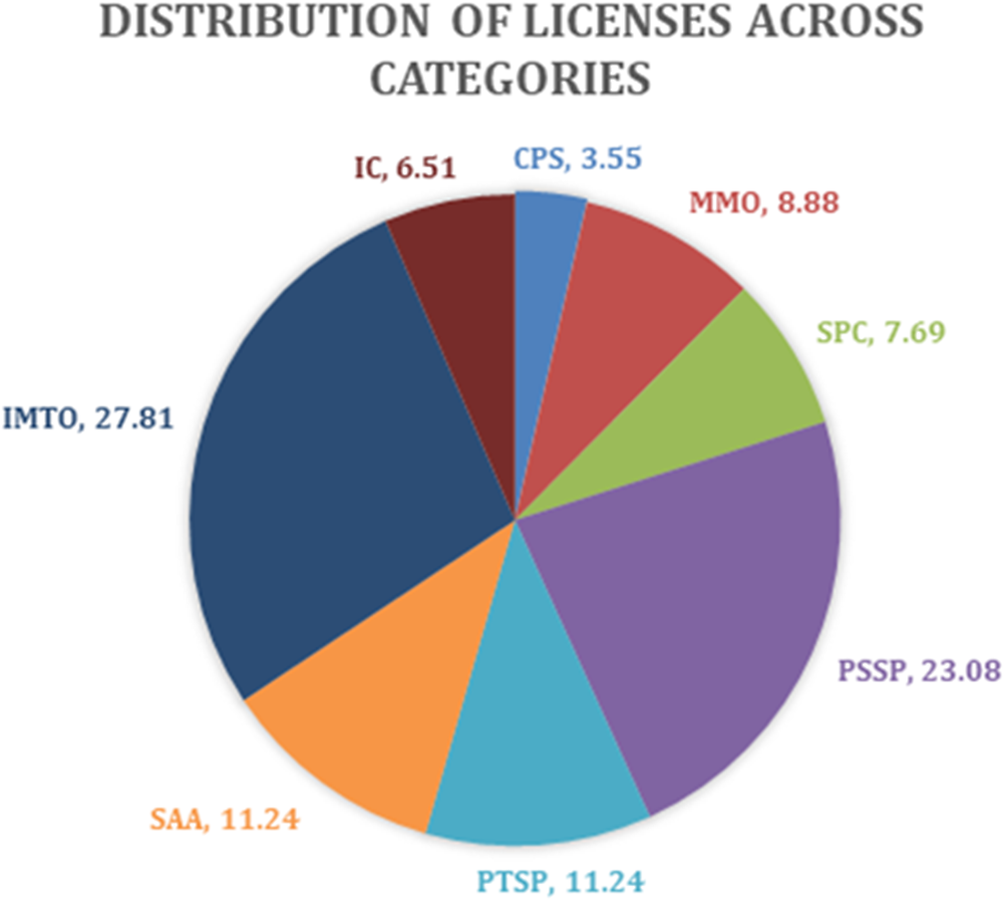

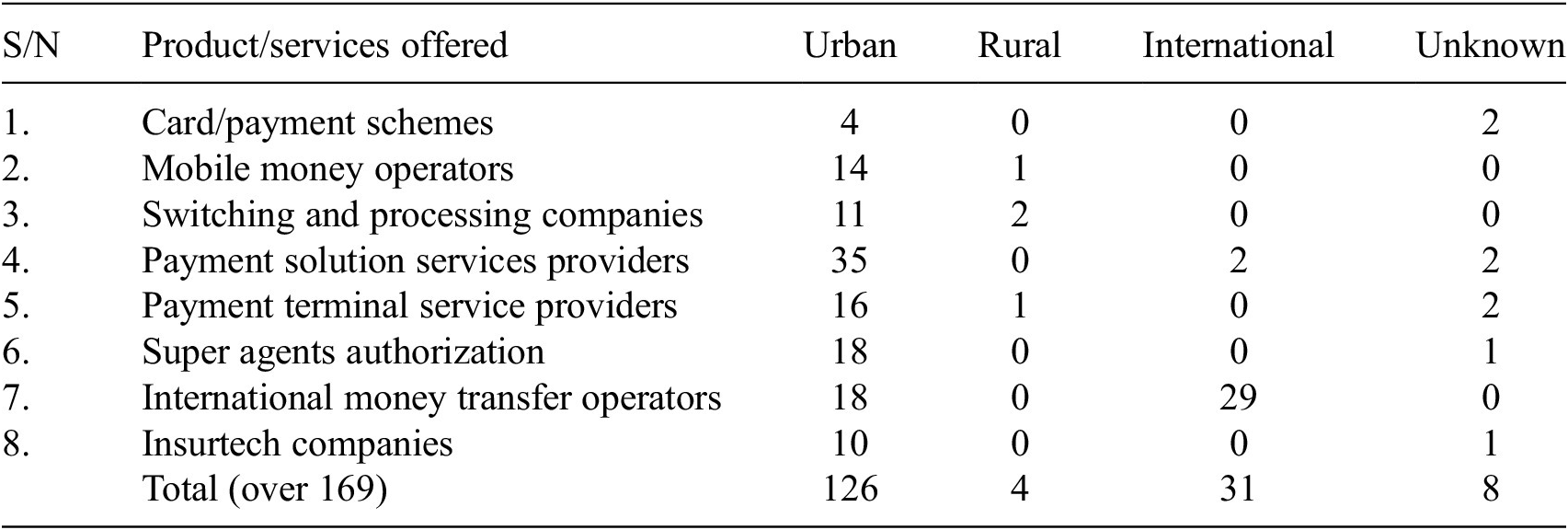

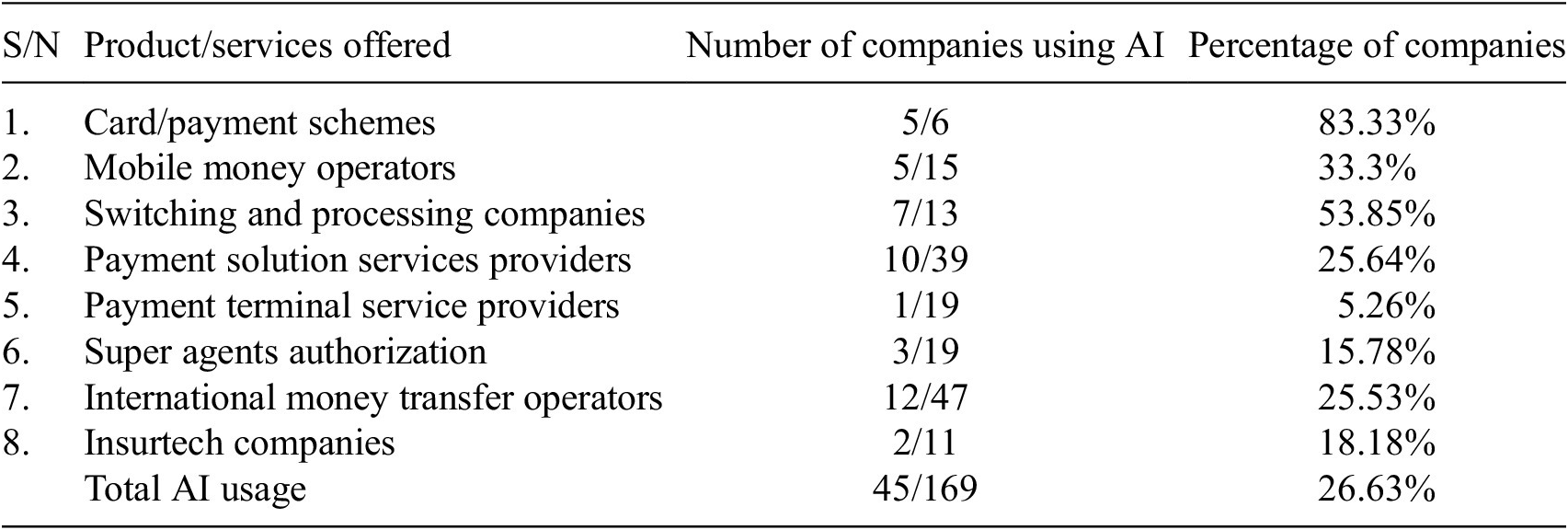

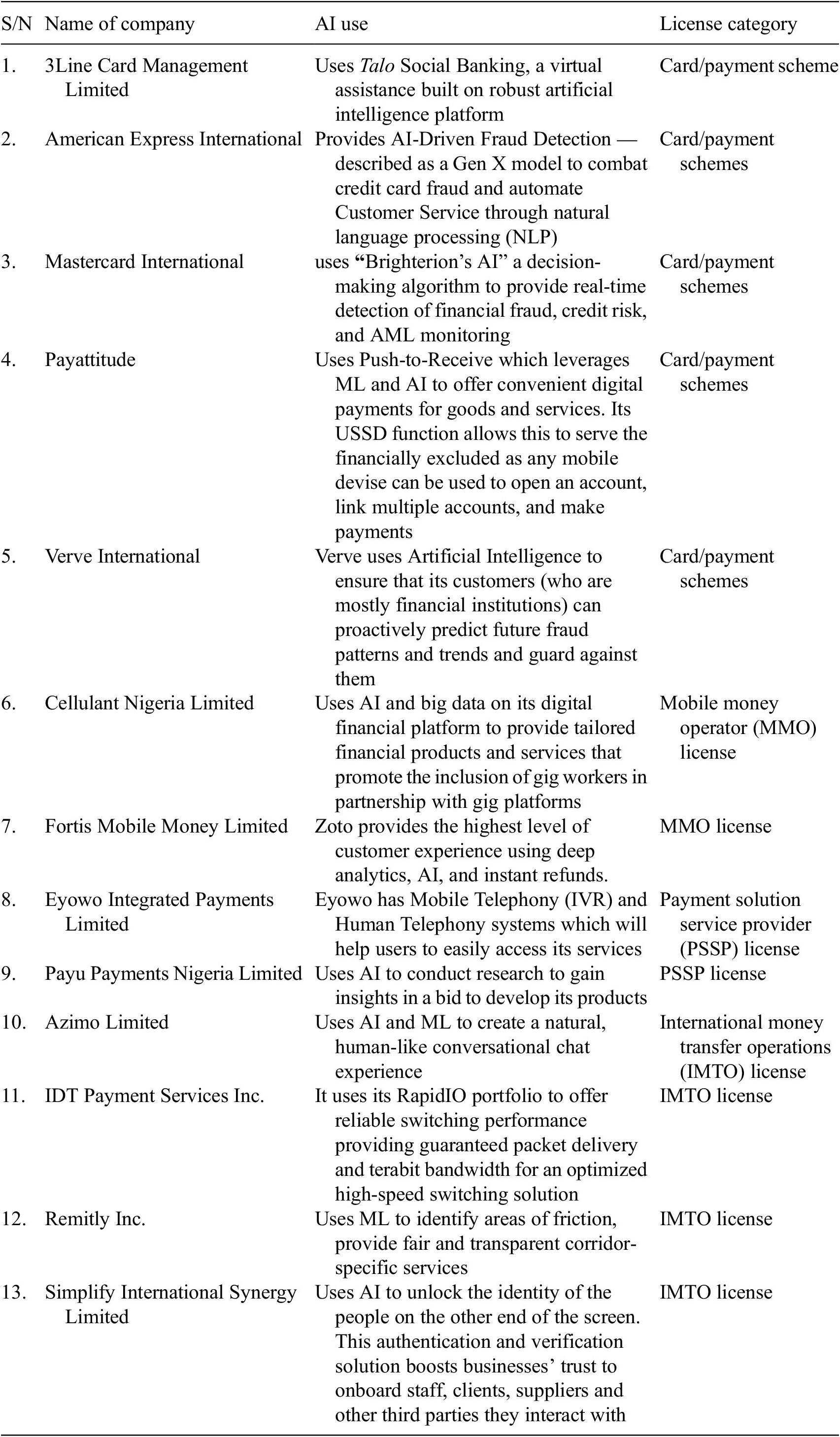

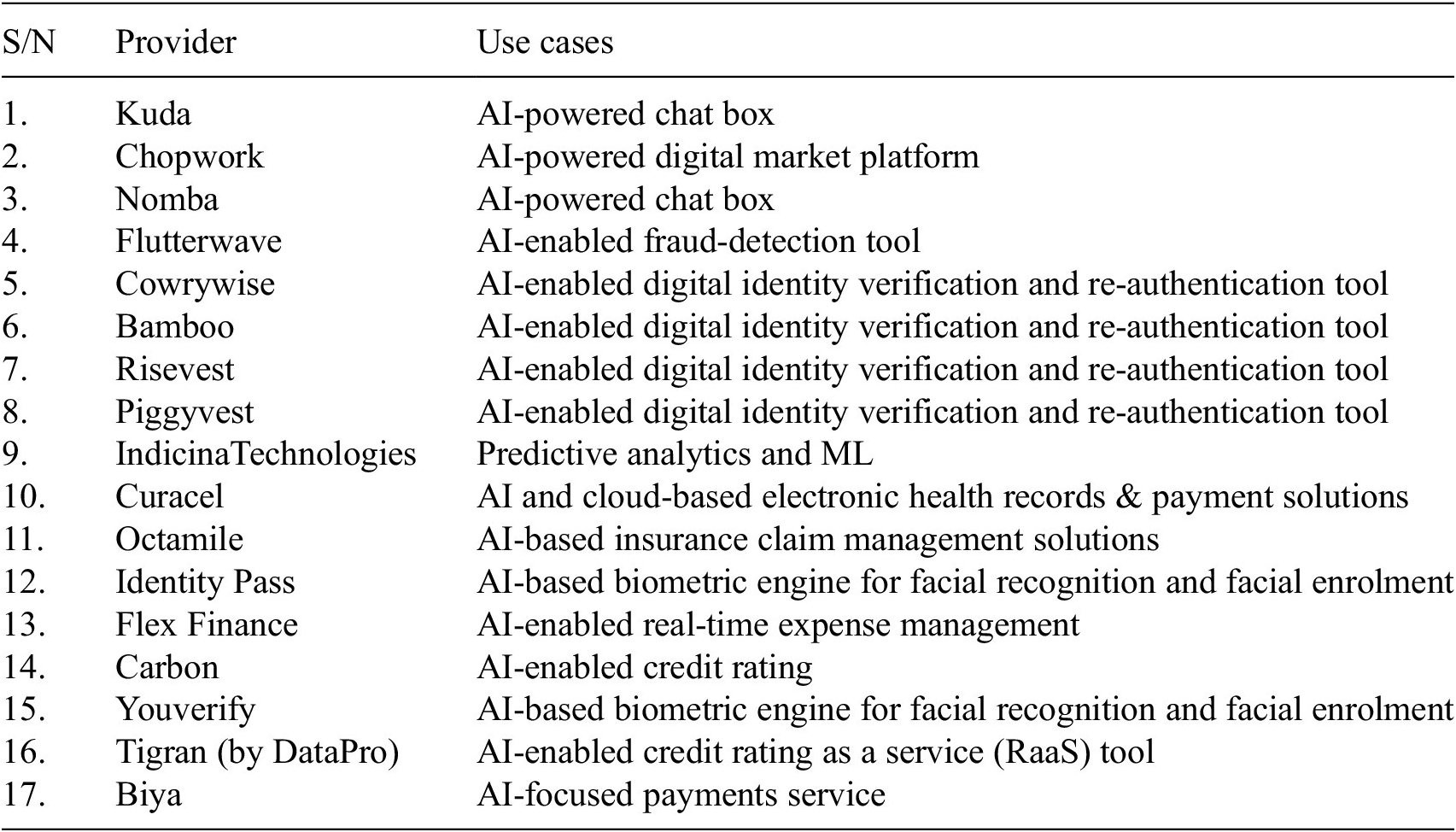

The research involved a survey of 169 licensed providers in different fintech categories (Table 3; Figure 1). The list of providers was sourced directly from publicly available information from financial sector regulators such as the CBN and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), and service providers’ websites. We also studied additional 17 financial service providers (Table 7) mainly because they use AI and offer their services to Nigerian consumers, although some are not registered under the fintech category or at all under Nigerian law, and may therefore not be subject to regulation by the CBN or SEC (Table 8). We found that most fintech service providers are in and operated from urban areas, particularly capital cities (Tables 3 and 5). Based on the information provided on their respective websites, 45 out of the 169 fintech providers claim to use AI (Table 6). Out of these, however, only 13 fully describe their AI, how it is integrated into their services or the specific use cases (Table 7). The survey is described more fully below under the four headings: number and categories of licensed fintech (A), Location or geographical spread of fintech providers (B), number of providers using AI (C), and AI use cases (D).

Table 3. A. Number of licensed providers per category (CBN, Reference Stumpf, Peters, Bardzell, Burnett, Busse, Cauchar and Churchill2020)

Table 4. B(I). Location/base of operation of fintech companies

Figure 1. Licence distribution.

Table 5. B(II). Urban and rural spread of fintech companies

Percentage of fintech companies spread: urban, 75%; rural, 2%; international, 18%; unknown, 5%.

Table 6. C. AI use cases: providers (claiming to use) AI

Note: Percentage of AI use cases in the FINTECH sector: AI use, 26.63%; no AI use, 73.37%.

Table 7. D(I). AI use cases.

Table 8. D(II). Use cases by unregistered/unlicensed providers

4. Discussion and analysis

4.1. Licensed fintech and use cases (indicators A, C, and D)

Table 3 shows that among licensed operators, only mobile money operators (MMO), payment solution service providers (PSSD) and super-agent authorisation appear to offer basic or consumer-facing services like payments and savings, which financially excluded women may need (WFID, 2022). Eighteen out of 169 licensed operators hold these licenses, others in the table appear focused on optimising existing financial products and services and offering sophisticated value-added services, such as trading platforms, and international money transfers, arguably for the already financially included. A reasonable inference is that products that are not relevant to women’s needs will aggravate demand related barriers, while limited licenses to providers of products likely to address such needs widen supply related barriers.

The AI use cases show the same pattern. Although about 45 providers claim to use AI (Table 5), only 13 provide information on their use cases (Table 6). For those without information, it is not clear whether they actively use AI, are in the process of developing their AI tools, or merely include AI to hype their services. Out of the 13 that do use AI, 2 are MMOs and 2 are PSSPs (Table 7). Again, both are the only providers likely to offer consumer-facing services which may be used by financially excluded women, particularly in rural communities. The others are focused on value-added services for theirs or other service providers’ existing products. This corresponds to already identified AI use cases by Fintech in Nigeria. Most fintech services are focused on guaranteeing the optimal performance of theirs or (others) financial products and services, differentiated customer experience, mitigating fraud and fraud detection, and enhancing financial advisory services, price regulation, marketing and managing insurance policies and portfolio and wealth management (Kola-Oyeneyin et al., Reference Kola-Oyeneyin, Kuyoro and Olanrewaju2020; Agidi, Reference Agidi2019). The 17 unlicensed and/or unregulated providers in Table 8 are unlikely to make a difference. They mostly help traditional financial service providers and other fintech providers serve their customers through, for example, providing identity verification services and chatbot services, fraud detection and digital market platforms. Crucially, no service provider seems to offer AI-powered products or services specifically (designed) for women.

There is currently no empirical evidence detailing the motivations behind financial product design, specifically concerning women’s diverse financial needs. However, one can theorise that woman, who are not a monolithic group, might avoid certain financial products due to the lack of “gendered” options that address their varied needs. Research indicates that excluded women may prefer financial services that support savings and micro-credits, as evidenced by the 6.3 million unbanked women in Nigeria who rely on informal savings collectors and merchants (WFID, 2022). Inclusive design, which should prioritise the end-user’s perspective, is crucial for catering to women’s unique financial needs. This concept aligns with Newell and Gregor’s approach to user-centred design for universal usability, advocating for designs that consider the specific characteristics of users, including those with disabilities (Stumpf et al., Reference Stumpf, Peters, Bardzell, Burnett, Busse, Cauchar and Churchill2020; Newell and Gregor, Reference Newell, Gregor and John2000).

The inference can be drawn that complex financial products, such as investment advisory services and trading platforms, may fail to attract certain demographics, like unbanked women, due to their lack of user-centric design and failure to meet the users’ specific needs (Brett et al., Reference Brett and Richard2021, Newell and Gregor, Reference Newell, Gregor and John2000). This gap in design and relevance leads to a diminished interest in learning or trusting the technologies. In Nigeria, a survey showed that while 74% of traders were open to adopting new technologies, over 30% resorted to informal financing due to denial of credit by financial institutions. Notably, most required funds below N30,000 (less than $40), leading to a decline in confidence in financial institutions, a preference for alternative solutions, and reduced willingness to engage with new financial technologies (Omoruyi, Reference Omoruyi2022, Prove, 2022).

4.2. Geography—the urban versus rural divide (indicator B)

Tables 4 and 5 show that most fintech service providers are in or operated from big urban cities like Lagos and Ibadan in Southwest Nigeria. Ordinarily, the location of a fintech might not be significant. Unlike banks, microfinance companies and other traditional financial service providers which rely on proximity to consumers and extensive branch networks to penetrate rural communities, fintech services are mostly digitalised and can be offered from any location. Thus, the models of Fintech companies allow them to bridge this proximity gap and provide services digitally to customers with no geographical boundaries (Frost, Reference Frost2022). M-Pesa, a Kenyan FinTech company, is one of the largest mobile money services in Africa. It operates in multiple countries across East Africa, North Africa, and South Asia, and has about 32 million users in 2018 (Njugunah, Reference Njugunah2022).

Nevertheless, proximity between a financial service provider and customers may be important regardless of the nature and type of service or mode of delivery (Saiedi et al., Reference Saiedi, Mohammadi, Broström and Shafi2022). Lack of awareness is a known cause of financial exclusion (Popescu, Reference Popescu2019), and the location of a fintech provider and its operations may be key to creating awareness in areas with high financial exclusion rates. Locating operational offices close to target users or consumers can create familiarity and make sensitization about products and services easier (Morgan and Trinh, Reference Morgan and Trinh2019). Awareness is also connected to digital and financial literacy. A case can be made that the closer providers are to the communities they serve, the easier they can understand the digital and financial literacy needs and address them (Kaffenberger et al., Reference Kaffenberger, Edoardo and Soursourian2018). Consumers are also more likely to trust providers that are close to them or have physical presence or representatives. This is particularly correct as concerns about privacy and data protection have increased with the proliferation of digital technologies.

For providers using or intending to use AI, trust will be critical to research and data collection, particularly where historical datasets are unavailable. Financial data, being particularly sensitive, are influenced by privacy and data protection concerns which may vary by gender. For example, women may be more hesitant to share personal information (Allen, Reference Allen2000; Park, Reference Park2015). This gender-based reluctance can affect AI training datasets despite assurances of beneficial use if the providers are lesser-known. Conversely, women may be more willing to trust established and proximate micro-finance institutions for services like credit eligibility assessments. According to Fu and Mrinal Mishra (Reference Fu and Mishra2021), the elements of trust in the fintech space include the number of years since a company was established as a measure of stability; whether the provider is headquartered in the same country/locality (as opposed to foreign entrants) as measures of geographic/cultural proximity; number of registered trademarks; and number of media articles as measures of reliability and familiarity respectively.

Perhaps, banks and fintech are developing more collaborations for this reason. Kuda, a digital bank, partnered with GT Bank and Zenith Bank to allow Kuda customers to make over-the-counter deposits at its branches to fund their Kuda accounts. Cowrywise similarly partnered with Sterling and Wema Banks to hold the funds of customers saved on Cowrywise. Piggyvest entered a deal with Providus Bank to create direct deposit account numbers for FinTech’s users (Prove, 2022). However, these partnerships are not always helpful as they tend to lock in existing customers and can perpetuate financial exclusion. This is explained in the next section.

4.3. Understanding the gender-blind approach to AI in finance

The preceding sections reveal fintech’s inadequacies in addressing women’s financial exclusion, regardless of AI integration. Beyond statistics, hindrances to AI’s role in women’s financial inclusion encompass factors like AI technology’s inherent nature, design and policy choices, and profit-centric business models.

4.3.1. Business models

From a business standpoint, profit priorities may supersede societal needs, leading to AI deployment focused on established markets rather than developmental challenges like financial inclusion. Developers may target already financially included customers for profitability, potentially neglecting underserved demographics. Licensing requirements, such as substantial minimum capital (250 million naira for PSSs consisting of super agents, PTSPs and PSSPs, 50 million for super agents, 100 million PTSP and PSSPs, and 2 billons for MMOs) mean start-ups face significant financial prerequisites. To meet these capital requirements, regulated entities may have to raise (new) capital or decrease assets (Yilla and Liang, Reference Yilla and Liang2020). Decreasing assets can lead to credit rationing or raise the cost of credit, especially for riskier borrowers like unbanked and underserved women (Sousa, Reference Sousa2015). To raise capital, fintech start-ups often turn to venture capital investors whose profit orientation may drive them to invest in a “safe” or tested market for the already financially included (Chhaidar et al., Reference Chhaidar, Abdelhedi and Abdelkafi2022; Okamgba, 2022). High capital requirements can also create monopolies where established and better-funded players dominate the fintech space. Telecom companies with large customer bases are poised to play an important role in MMOs (NCC, 2021), and banks are increasingly collaborating with fintech (NCC, 2021, para 3.2).

While collaborations are important elements of fostering trust, it can also entrench banks’ monopolies or create new ones or even perpetuate exclusion. Existing customers of banks may automatically be integrated into the fintech market, given the necessary financial literacy skills, technology support and training required to navigate fintech products, much better than new fintech entrants who may struggle to recruit customers. The critical question is therefore whether bigger players are interested in leveraging new technologies for inclusive service or simply increasing their market share by edging out new start-ups. A recent report raises similar concerns when it noted that while several leading banks recognise the women’s market as a key strategic opportunity and the theoretical business case for serving women, only a handful have developed a targeted women’s market proposition and most remain in the pilot stage (WFID, 2022).

4.3.2. Gender bias and other AI risks

Perceptions of technology as “neutral” in the context of financial inclusion often assume equal benefits for all users, irrespective of gender. However, the mobile gender gap exemplifies that technology, including AI, does not inherently ensure access or inclusion for women. Within finance, notable concerns surrounding AI include the risks of bias and disparate impact on credit outcomes, stemming from inaccurate, non-representative, and low-quality data. ML-based decision models are likened to a “black box” due to apprehensions regarding transparency, explainability, and fairness (OECD, 2021).

In the Nigerian fintech landscape, these challenges are compounded. Women’s underrepresentation in datasets used for financial decision-making, rooted in historical exclusion from financial access, may result in AI systems perpetuating existing biases. Particularly evident is the gender credit gap, globally accounting for $17 billion, and primarily attributable to discriminatory practices in AI-enabled credit scoring tools employed by fintech companies (Women’s World Banking, 2021). The reliance on digital footprints for dataset creation poses further challenges, as women tend to lag men in mobile device ownership, (GSMA, 2022) limiting their visibility in current datasets.

Moreover, constraints arise from the difficulty of AI designers and developers in accessing gender-disaggregated data for algorithm training, hindering the development of financial products that cater to the specific needs of women. Despite recent mandates for service providers to collect such data, the effectiveness of individual organizations, especially start-ups, in fulfilling this obligation remains uncertain. While big data analytics and AI enhance data accessibility, challenges persist in collecting data in rural communities with low levels of mobile and smartphone ownership among women, potentially increasing perceived risks and discouraging investment in gendered AI financial products.

4.3.3. Policy and regulatory constraints

Using AI for financial inclusion evidently requires regulation to address biases in the data and algorithms, which may affect women disproportionately, particularly as gender bias is a known problem in the AI community (Criado-Perez, Reference Criado Perez2019). The push for policy interventions for “responsible AI” encompassing attributes like fairness, transparency, inclusiveness and explainability of AI models must therefore be considered in the context of poor and illiterate women and those living in rural communities. Can they understand the explanation underpinning AI decision-making, assuming such an explanation is possible and available? or will AI decision-making, or the complications of explanation undermine trust in the system and make the unbanked less disposed to accepting the technology?

Extant policy guidelines on fintech (discussed in Section 1.3) do not address the peculiar risks and challenges of AI or its gender-related problems (discussed above and in Section 2). An important concession made by the financial regulator is that policies are developed on the assumption that they are gender neutral when in fact they impact men and women differently (CBN, Reference Stumpf, Peters, Bardzell, Burnett, Busse, Cauchar and Churchill2020). Equally, a gender-blind policy approach to AI may create problems. It could breach the UNSDG 5 which urges member states to strive to achieve gender equality and empower all women by enhancing enabling technologies and adopting and strengthening sound policies and enforceable legislation. Disparate and overlapping guidelines and frameworks for fintech could create compliance burdens that disincentive start-ups in the relatively unchartered sphere of “gendered” innovations. While policy responses to women’s financial exclusion and fintech are relatively nascent—starting from 2018—the metrics for their success are difficult to assess. For example, policy aspirations to innovate to (women’s) needs (CBN, Reference Stumpf, Peters, Bardzell, Burnett, Busse, Cauchar and Churchill2020), are not matched by proposals or calls and funding for empirical research to understand what women’s financial service needs are. There is no legal requirement to collect gender-disaggregated data expected to aid the development of financially sustainable products and delivery systems that respond to low-income women’s needs (CBN, Reference Stumpf, Peters, Bardzell, Burnett, Busse, Cauchar and Churchill2020). While the NFS identifies regulatory clarity particularly towards an innovation-friendly environment, as a critical resource for its success (CBN, 2022a), it is not clear how this can be achieved without specific policies and regulation on emerging technologies like AI.

Proactive policy initiatives must be aimed at mitigating discrimination in AI outcomes and support historically marginalized groups such as women by focussing on algorithmic transparency. Additionally, policies should encourage (through empirical research) the inclusion of women’s experiences in financial product design and emphasise the importance of collecting and applying gender-disaggregated data. Policymakers are encouraged to create guidelines and toolkits that promote Gender Equality and Inclusion by Design to aid private sector players in identifying and reducing exclusionary risks during the development and throughout the lifecycle of AI technologies in critical sectors such as finance.

5. Conclusion

This paper has outlined the extent of women’s financial exclusion in Nigeria, examined the growth of the fintech sector and the utilisation of AI in finance, and considered potential implications for women’s inclusion. Merely introducing innovative financial services and technology is insufficient to ensure inclusion. To achieve financial inclusion, services must be available, accessible, affordable, appropriate, and sustainable, and aligned with the needs of potential users. However, the paper’s analysis shows that, despite the promise of AI, it has not significantly impacted women’s financial inclusion. Women are less likely to utilise complex financial services due to digital literacy barriers, and trust issues may arise when service providers are geographically distant from potential users, even if their services are fully digital. While the argument for AI’s ability to enhance efficiency, reduce transaction costs, and improve profitability is well-established, the challenge lies in serving the substantial yet underserved women’s market. Increasing women’s financial inclusion and their economic participation necessitates deliberate design choices aimed at addressing inclusion barriers and meeting the specific needs of women.

Beyond its policy implications, this research contributes to theoretical frameworks aimed at explaining social inequalities based on gender. For example, the intersection of geographical locations with women’s financial exclusion highlights the complexities of addressing inequalities and the effects of the behaviours of social actors on economic and development outcomes. This could prompt longitudinal studies to track changes in women’s financial inclusion over time in response to AI interventions across disciplines like economics, data science, law and policy and gender studies.

However, the research prompts further inquiry beyond its scope: empirical research to understand women’s unique financial service needs to drive gendered innovations, raising awareness of women’s financial exclusion within the design community, and identifying additional factors influencing design choices. Moreover, it is critical to evaluate whether legal and policy interventions and fintech regulatory models adequately address the gendered risks associated with AI while harnessing its potential benefits for women’s financial inclusion.

Acknowledgements

The author expresses gratitude for the valuable contributions of Nelson Iheanacho, Amirah Rufai, Thummim Iyoha-Osagie, and Maxwell Igweogu who served as research assistants on the project.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: A.O; Formal analysis: A.O; Funding acquisition: A.O; Investigation: A.O; Methodology: A.O; Project administration: A.O; Resources: A.O; Supervision: A.O; Validation: A.O; Writing—original draft: A.O; Writing—review & editing: A.O.

Data availability statement

This is not an empirical work. The data utilised in this paper has been sourced from publicly available repositories and is accessible without any restrictions as follows.

-

1. EFInA (2021) Access to financial services in Nigeria 2020 survey. Available at https://efina.org.ng/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/A2F-2020-Final-Report.pdf (accessed 11 March 2024).

-

2. EFInA (2018) Access to financial services in Nigeria 2018 survey. Available at https://efina.org.ng/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/A2F-2018-Final-Report.pdf (accessed 11 March 2024).

-

3. EFInA (2017) Access to financial services in Nigeria 2016 survey. Available at https://efina.org.ng/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/A2F-2016-Final-Report.pdf (accessed 11 March 2024).

-

4. EFInA (2014) Access to financial services in Nigeria 2014 survey. Available at https://efina.org.ng/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/A2F-2014-Final-Report.pdf (accessed 11 March 2024).

-

5. EFInA (2012) Access to financial services in Nigeria 2012 survey. Available at https://efina.org.ng/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/A2F-2012-Final-Report.pdf (accessed 11 March 2024).

-

6. EFInA (2010) Access to financial services in Nigeria 2010 survey. Available at https://efina.org.ng/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/A2F-2010-Final-Report.pdf (accessed 11 March 2024).

-

7. EFInA (2008) Access to financial services in Nigeria 2008 survey. Available at https://efina.org.ng/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/A2F-2008-Final-Report.pdf (accessed 11 March 2024).

-

8. World Bank, Global Findex Database. Available at https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/globalfindex/Data

-

9. World Bank, Global ID4D Findex survey data. Available at https://id4d.worldbank.org/global-dataset (accessed 11 March 2024).

-

10. Central Bank of Nigeria & EFInA Report (2019) Assessment of women’s financial inclusion in Nigeria. Available at https://efina.org.ng/publication/assessment-of-womens-financial-inclusion-in-nigeria/ (accessed 11 March 2024).

-

11. GPFI Report (July Reference Stumpf, Peters, Bardzell, Burnett, Busse, Cauchar and Churchill2020) Advancing women’s digital financial inclusion. p. 27 Available at https://www.gpfi.org/sites/gpfi/files/sites/default/files/saudig20_women.pdf (accessed 11 March 2024).

-

12. CBN (9 December Reference Stumpf, Peters, Bardzell, Burnett, Busse, Cauchar and Churchill2020) New licence categorisation for payment systems in Nigeria. Available at https://www.cbn.gov.ng/Out/2020/CCD/Categorization%20of%20PSPs.pdf (accessed 11 March 2024).

-

13. Talo Social Banking. Available at https://www.3lineng.com/solutions.html#social-banking-solution (accessed 11 March 2024).

-

14. TheBrighterion-Mastercard AI. Available at https://brighterion.com/#:~:text=Brighterion%20has%20revolutionized%20AI%20for,scalability%20your%20growth%20is%20limitless (accessed 11 March 2024).

-

15. PayAttitude Digital (nd). Available at https://up-ng.com/index.php?id=17 (accessed 11 March 2024).

-

16. Verve International, Business. Available athttps://www.myverveworld.com/ng/business (accessed 11 March 2024).

-

17. Increasing financial inclusion through AI (2021) Available at https://corporate.payu.com/blog/increasing-financial-inclusion-through-ai/; PAYU, Privacy Statement Nigeria. Available at https://nigeria.payu.com/privacy-statement-nigeria/ (accessed 11 March 2024).

-

18. Remitly (nd) Available at https://careers.remitly.com (accessed 11 March 2024).

-

19. Simplify-ID, Available athttps://simplifysynergy.com/our-products/simplify-id/ (accessed 11 March 2024).

Provenance

This article is part of the Data for Policy 2024 Proceedings and was accepted in Data & Policy on the strength of the Conference’s review process.

Funding statement

This research was supported by the African Observatory on Responsible AI, a grant funded by the International Development Research Centre of Canada (grant No 109652).

Competing interest

The author declares none.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.