Iodine-deficiency disorders, caused by low dietary intake of iodine, are major causes of preventable developmental disabilities and conditions such as goitre, which is why they are of major concern during pregnancy and childhood( Reference Bailey, West and Black 1 ). The WHO and UNICEF have long recommended universal salt iodization standards to achieve elimination of iodine-deficiency disorders( 2 ). The recommendations for universal salt iodization are that processed edible salt globally be adequately iodized. In Kenya, legislation on mandatory salt iodization was passed in 1978 and revised in 1988( 3 , Reference Tran, Hetzel and Fisher 4 ). Surveys on iodine-deficiency disorders undertaken in 1994 and 2004 showed that the prevalence of goitre among children aged 8–10 years had decreased from 16 to 6 %, respectively( Reference Gitau 5 ). This improvement is attributed to the increase in consumption of iodized salt by most (91 %) Kenyan households.

In Kenya, salt iodization is legislated in the Foods, Drugs and Chemical Substances Act, Chapter 254, article 299, which states that table salt should contain a minimum of 50 mg of potassium iodate (KIO3) per kilogram( 3 ). However, as a demonstration of good manufacturing practice, manufacturers are required to add more than 50 mg KIO3/kg because iodine and its derivatives easily dissociate with time as salt moves from the manufacturer to the retail establishment. The present study aimed to: (i) measure KIO3 levels in edible salts sold at retail shops throughout the country; and (ii) determine whether the salts sold in retail outlets meet government standards for salt iodate content.

Methods

As part of the Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2013, field workers collected iodized salt samples from randomly selected retail establishments across eight regions of the country. One sample of each brand of the packaged salts that were available in the sampled retail shops was collected. All the sampled salts from the eight regions in the country were delivered unopened to the National Public Health Laboratory (NPHL) for analysis.

General titration methods were used to determine KIO3 of the submitted samples. Titration was continued until the concentration of KIO3 was calculated from the fact that 1 ml of 0·005-M sodium thiosulfate reacts with 0·635 mg of iodine. Data for each sample were entered into a Microsoft® Excel 2007 spreadsheet and descriptive statistics were calculated.

Results

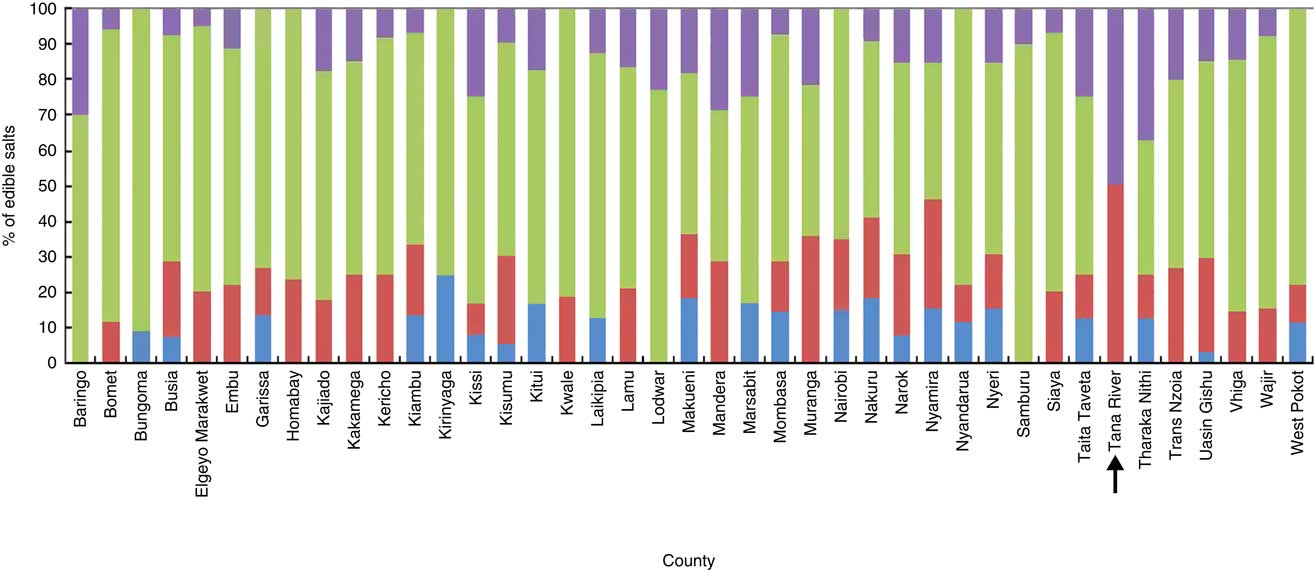

A total of 539 salt samples were analysed, with mean of 62 mg KIO3/kg. Thirty-three (6 %) of the samples had KIO3 levels of <25 mg/kg; ninety-eight (18 %) had 25–49 mg/kg; 335 (62 %) had 50–84 mg/kg; and seventy-three (13 %) had KIO3 of >84 mg/kg. When the data were analysed by region, we noted that the Eastern region had the highest mean KIO3 of 65·9 mg/kg, followed by Nyanza (63·5 mg/kg), Rift Valley (63·4 mg/kg), Northeastern (62·7 mg/kg), Western (62·0 mg/kg), Coast (61·8 mg/kg), Central (57·4 mg/kg) and Nairobi with the least at 51·7 mg/kg (Table 1). There was a good distribution of KIO3 levels in all forty-one counties sampled. Tana River, one of the poorest and most vast counties, had half of the sampled salts in the 20–49 mg/kg range (Fig. 1, arrowed).

Fig. 1 (colour online) Potassium iodate levels (![]() , <25 mg/kg;

, <25 mg/kg; ![]() , 25–49 mg/kg;

, 25–49 mg/kg; ![]() , 50–84 mg/kg;

, 50–84 mg/kg; ![]() , >84 mg/kg) in processed edible salts available in retail stores, per county, Kenya, 2013 (n 539)

, >84 mg/kg) in processed edible salts available in retail stores, per county, Kenya, 2013 (n 539)

Table 1 Status of iodized salt per region, Kenya Demographic and Health Survey, 2013 (n 539)

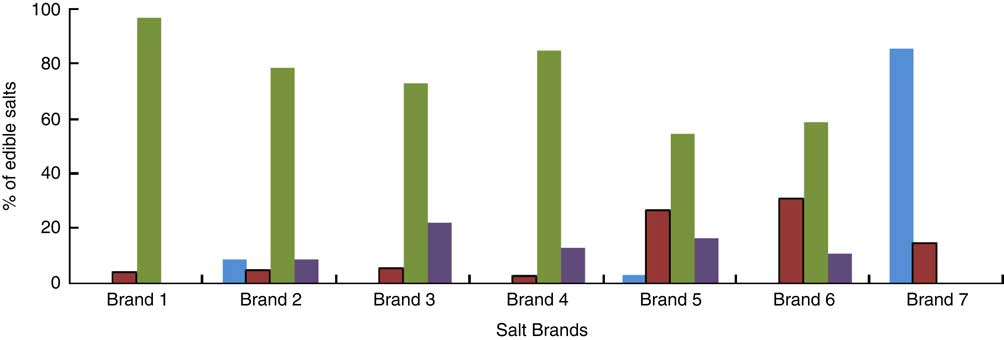

Of the 539 salt samples analysed, brand 3 had the highest mean KIO3 level of 75 mg/kg with fifty-five salt samples analysed. Brand 5 had the largest number of salts analysed (264, i.e. 49 % of all the salts), with a mean KIO3 level of 62 mg/kg. This brand was present in all forty-one counties and its KIO3 levels were as follows: 3 % had <25 mg/kg; 27 % had 25–49 mg/kg; 55 % had 50–84 mg/kg and 16 % had >84 mg/kg. Brand 7 had twenty-seven salt samples analysed and had the lowest mean KIO3 level of 13 mg/kg. Its KIO3 levels were as follows: 85 % had <25 mg/kg and 15 % had 25–49 mg/kg. Brand 7 also had the salt sample with the lowest KIO3 (0 mg/kg). Overall, 24 % of the samples were below the 50 mg/kg threshold and 13 % of the samples were above the mandated maximum (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 (colour online) Potassium iodate levels (![]() , <25 mg/kg;

, <25 mg/kg; ![]() , 25–49 mg/kg;

, 25–49 mg/kg; ![]() , 50–84 mg/kg;

, 50–84 mg/kg; ![]() , >84 mg/kg) in processed edible salts available in retail stores, per brand, Kenya, 2013 (n 539)

, >84 mg/kg) in processed edible salts available in retail stores, per brand, Kenya, 2013 (n 539)

Discussion

The national mean KIO3 level was 62 mg/kg for all salts sampled. This indicates that Kenyans are consuming iodized salt. These study findings are similar to observations from 2010 that most households in Kenya were using adequately iodized salt( Reference Tran, Hetzel and Fisher 4 ). All brands sampled met the required KIO3 level except for brand 7, which had 85 % of the salts sampled below 25 mg KIO3/kg and 15 % with 25–49 mg KIO3/kg. Possible reasons for this could be that the company producing brand 7 was not iodizing its salt properly or the salt was iodized properly but staying too long on the shelves and lost the iodate through chemical dissociation combined with lack of proper quality assurance in the factory. According to another global study, packaging salt in an effective moisture barrier, such as solid low-density polyethylene bags, can reduce iodine losses significantly( Reference Diosady, Alberti and Mannar 6 ). The present study also corroborates that of Kishoyian et al., who studied six different salt brands in two primary schools in Nairobi, Kenya and found that the iodate levels varied significantly between 2·02 and 191·5 mg/kg( Reference Kishoyian, Njagi and Orinda 7 ).

There was a relatively stable distribution of salt KIO3 levels in the eight regions. However, two regions of the country, Nairobi and Central, had the lowest mean levels of KIO3. Their mean values were just barely meeting the lower limit of KIO3 recommended for iodization.

Conclusion

Results from the current study indicate that Kenya is not in compliance with the universal salt iodization recommended level for processed edible salts and that there is ample room for improvement of the iodized salt supply. The study illustrates the critical utility of retail monitoring as it identified two salt brands with mean KIO3 content outside the mandated range. Therefore, the Ministry of Health should continuously monitor KIO3 levels in Kenyan salts in all regions, to adequately inform relevant stakeholders on the trends of salt iodization. Monitoring will also assure that companies producing edible salts adequately iodize their salts. By doing this, we can reduce the incidence of iodine-deficiency disorders in Kenya even further.

Acknowledgements

Financial support: This work was supported by the Kenya Demographic and Health Survey, which received funding from the Kenya Ministry of Health. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and not official statements or conclusions of the Ministry of Health, the Field Epidemiology and Laboratory Training Program, or of the National Public Health Laboratory. Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Authorship: The study design was developed by G.G.G. and J.M.; G.G.G., N.N., J.N. and J.M. described the laboratory procedures; data collection was supervised by G.G.G., N.N. and J.N.; data were analysed by G.G.G., N.N., J.N., J.M. and J.R.; G.G.G. and J.R. wrote the final versions of the manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: Not applicable.