Children’s low vegetable, berry and fruit consumption is a considerable nutritional challenge in Finland( Reference Kyttälä, Erkkola and Kronberg-Kippilä 1 , Reference Talvia, Räsänen and Lagström 2 ) and around Europe( Reference Lynch, Kristjansdottir and te Velde 3 ). Vegetables, berries and fruit are an essential source of phytochemicals( Reference Liu 4 ) and their nutritional properties, such as low energy and high nutrient density, provide a way of promoting health.

Increasing children’s consumption of vegetables, berries and fruit is challenging because food choices are affected by both environmental input and individual characteristics( Reference Johnson 5 ). For example, the former is affected by parents’ socio-economic factors, which reflect on their food choices, varying parenting practices related to food and lack of conscious food education in early childhood education and care (ECEC). The latter involves factors such as children’s fussiness and food neophobia, which challenge children’s learning in eating vegetables, berries and fruit.

ECEC has crucial potential for food education: the majority of Finnish children participate in high-quality early childhood education( 6 ) which includes supervised, nutritious meals and where the children are involved in various pedagogic activities. Some ECEC centres in Finland implement sensory-based food education in addition to standard curriculum-based ECEC, which emphasises the role of the centre in children’s food education. In Finland, the experiences gathered from child-oriented sensory-based food education provided in ECEC have been positive and encouraging. Consequently, an increasing number of municipalities and ECEC centres have included sensory-based food education in their local early childhood education curricula( Reference Sandell, Mikkelsen and Lyytikäinen 7 ). In order to guide ECEC to implement sensory-based food education, more evidence-based knowledge is needed about its association with children’s fruit and vegetable choices as well as the related moderating factors. Knowledge of associations between sensory-based food education in ECEC and children’s vegetable, berry and fruit consumption would benefit early educators and help understanding the role of ECEC in children’s food education and related opportunities.

Sensory food education encourages children to explore food options using all five senses( Reference Puisais and Pierre 8 ). Vegetables, berries and fruit are excellent food items for this type of education, as they are rich in qualities perceived through the senses of hearing, vision, olfaction, taste and touch. Sensory food education activities encourage children to participate, generate positive food experiences and instil the joy of eating in the children. Sensory food education has displayed potential in promoting children’s vegetable and fruit consumption( Reference Dazeley, Houston-Price and Hill 9 ).

Sensory food education has mostly been studied from the point of view of school-aged children. Previous studies have indicated that the education increases children’s abilities to describe foods( Reference Mustonen, Rantanen and Tuorila 10 ), promotes food talk( Reference Jonsson, Ekström and Gustafsson 11 ), and broadens children’s food preferences( Reference Mustonen and Tuorila 12 , Reference Reverdy, Schlich and Köster 13 ) and their willingness to eat unfamiliar foods( Reference Reverdy, Chesnel and Schlich 14 , Reference Battjes-Fries, Haveman-Nies and Renes 15 ). Based on these studies, sensory food education seems to have benefited school-aged children, although a recent study found a school-based sensory food education programme, ‘Taste Lessons’, to have produced no effect on children’s willingness to taste vegetables and fruit( Reference Battjes-Fries, Haveman-Nies and Zeinstra 16 ).

Few studies have explored sensory food education among children under school age. Research has thus far shown that food education increases the willingness of under-school-aged children to eat vegetables, berries and fruit( Reference Coulthard and Sealy 17 – Reference Hoppu, Prinz and Ojansivu 19 ). However, it remains unclear how such food education embedded in the ECEC curriculum would alter children’s attitudes towards vegetables, berries and fruit. Therefore, the hypothesis of the present study is that there is an association between sensory-based food education integrated into the ECEC routine and higher willingness to choose and eat vegetables, berries and fruit.

As a form of environmental input, parental education levels directly and proportionately affect the amount and frequency of children’s vegetable, berry and fruit consumption( Reference Fernandez-Alvira, Bornhorst and Bammann 20 – Reference Sausenthaler, Kompauer and Mielck 22 ). Low consumption is particularly related to the mother’s low level of education, indicating social inequity and the significance of price in consumption patterns( Reference Rehm, Monsivais and Drewnowski 23 ). We hypothesised that the children of parents with lower socio-economic status would have lower willingness to choose and eat vegetables, berries and fruit.

Children’s individual characteristics may also be relevant in affecting the variety of foods consumed and seem to be inversely associated with vegetable and fruit consumption( Reference Dovey, Staples and Gibson 24 , Reference Lafraire, Rioux and Giboreau 25 ). Neophobia, defined as reluctance to try and eat unfamiliar foods, is a common trait among children and can be alleviated by sensory food education( Reference Mustonen and Tuorila 12 , Reference Reverdy, Chesnel and Schlich 14 ). Food neophobia, measured using a ten-item questionnaire( Reference Pliner and Hobden 26 ), is typically considered an individual trait, although children are also responsive to social interaction, for example in child groups in ECEC. Hence, also considering food neophobia at the group level can provide insight into the perceptual world of children in social eating situations. Our final hypothesis is that food neophobia is inversely associated with participation in sensory-based food education in ECEC.

Using naturalistic settings and photographs in measuring young children’s food choices and intake is gaining popularity and has been found to be a valid and feasible research method( Reference Nicklas, O’Neil and Stuff 27 – Reference Perez-Rodrigo, Artiach Escauriaza and Artiach Escauriaza 29 ). Methodologically, one of the present study’s merits is measuring children’s vegetable, berry and fruit consumption and preferences in an objective and child-oriented manner, which allows the children to eat in a natural, real-life group situation. This method takes both children’s abilities and their developmental stage into account.

Our aim was to investigate whether sensory-based food education implemented in ECEC is associated with children’s willingness to choose and eat vegetables, berries and fruit. Furthermore, we studied the possible moderating role of socio-economic status and food neophobia.

Methods

Participants

The present study compared children attending two types of ECEC centres: six ECEC centres implementing sensory-based food education and three standard ECEC centres.

In total, sixty-eight children in ten child groups at the sensory-based food education centres (SEN) and sixty-two children in eight child groups in the standard centres, which served as a reference group (REF), participated in the study.

We excluded children who were not present at the snack buffet or who had participated in ECEC at the centres for less than 10 months. It was necessary to set this participation period criterion to investigate the role of the food education in children’s behaviour towards vegetables, berries and fruit( Reference Mustonen, Rantanen and Tuorila 10 , Reference Reverdy, Schlich and Köster 13 ). We also excluded children with food allergies, type 1 diabetes and coeliac disease.

The SEN and REF groups were similar in terms of the children’s ages, ECEC participation, family size and living arrangements (Table 1), as well as parental age, education level and working arrangements. The children were 3–5-year-old boys and girls participating in ECEC during daytime on most weekdays while most of their parents were at work. The majority of children lived with their mother and father, and the families had on average four members. Parents were typically in their thirties, and half of the mothers and a third of the fathers had a university degree.

Table 1 Background information of the 3–5-year-old children and their parents, Finland, 2014 and 2015

Data are missing data in some categories; statistics are based on available data.

SEN, sensory-based food education group; REF, reference group; ECEC, early childhood education and care.

We collected our data in autumn 2014 and autumn 2015, each of the ECEC centres participating either in 2014 or 2015. The SEN ECEC centres, which had been providing sensory-based food education since 2011, were located in Western Finland and the REF ECEC centres, which did not carry out equivalent food education, were in Eastern Finland. We selected the SEN centres from the ECEC centres that had been among the first to introduce sensory-based food education in Finland and were actively using the method. We selected the REF centres from municipalities which matched the regions of the SEN centres in terms of population and urban/ruralness to the extent possible.

The municipal ECEC directors and the managers of the participating ECEC centres also gave their consent. Parents signed an informed consent form, allowing their children to participate.

Sensory-based food education in early childhood education and care

Half of the children participated in ECEC implementing sensory-based food education. In ECEC in Finland, sensory-based (Sapere) food education is a modification from the French Le goût et l’enfant by Jacques Puisais and Catherine Pierre( Reference Puisais and Pierre 8 ). This modified version is a system whose educational activities have been developed to suit the age and developmental level of the young children in ECEC( Reference Sandell, Mikkelsen and Lyytikäinen 7 , Reference Ojansivu, Sandell and Lagström 30 ).

The method is integrated with daily routines and weekly ECEC activities. It is child-oriented and facilitates sensory learning by playing. The method values children’s experiences, encourages their self-expression, and promotes participation and enthusiasm. Early educators collaborate with children, making meals enjoyable, creating positive memory traces and instilling natural curiosity about food in the children.

In practice, this means including sensory sessions with food in the ECEC activities, integrating food education into food preparation and meals at ECEC, and inserting food themes into other ECEC activities( Reference Sandell, Mikkelsen and Lyytikäinen 7 , Reference Koistinen and Ruhanen 31 ). The practices, facilities, tools and frequencies used by the ECEC centres to implement sensory-based food education during meals and sensory sessions are described in Table 2. In the sensory sessions, where special emphasis is given to health-promoting foods such as vegetables, berries and fruit, children explore food items through the senses of hearing, vision, olfaction, taste and touch, and describe their observations together. Children participate in meal preparation by baking, preparing salads and desserts, and growing vegetables, fruit and berries together in an ECEC centre orchard, garden or windowsill. The children are given an active role at meals to portion their meals, set the tables and butter their bread. Special attention is also given to the way food is served, for example by separating salad ingredients. Food education is also integrated into short day trips, which involve visiting farms, markets or forests to learn about the origin of food. Other ECEC activities, such as playing, drawing, reading, singing and physical activities, include food themes that make food items and eating more familiar and more present for the children. The ECEC centres with sensory-based food education can also employ a pedagogical menu, a tool that facilitates organising sensory sessions and collaboration between early educators and catering staff. A pedagogical menu includes daily meals similarly as a regular ECEC menu. In addition, it integrates sensory sessions into meals by including a selection of food items to explore through the senses( Reference Sandell, Mikkelsen and Lyytikäinen 7 ).

Table 2 Sensory-based food education practices, facilities and tools at early childhood education and care (ECEC) centres (n 6), Finland, 2014 and 2015

Before the implementation of sensory-based food education in ECEC centres, their education personnel had been trained on the topic. All the early educators had participated in a 6 h training including lectures on child nutrition, the five senses and the principles of the sensory-based food education method, as well as sensory activities with vegetables, berries and fruit. After this training, 4 h workshops had been organised in the municipalities and had the purpose of seeking ways to put the method into practice in the ECEC centres. Additional training of 6 to 12 h had been offered on child nutrition and the Nordic Nutrition Recommendations for all ECEC educators, catering staff and the managers of ECEC centres in the municipalities. Finally, one or two ECEC educators per municipality, who had participated in a Sapere instructor training for a total of 24 h, were put in charge of coordinating local activities, enhancing collaboration and providing information about the method in their municipality. Each participating ECEC centre also received a handbook on sensory-based food education and its implementation in ECEC( Reference Koistinen and Ruhanen 31 ). Moreover, all the training material and inspiration to the implementation was available for everyone through a website.

As a part of the municipal early childhood education curriculum, sensory-based food education brings together mathematical, scientific, historical, sociological, aesthetic, ethical and religious education contents of ECEC( Reference Ojansivu, Sandell and Lagström 30 ). In comparison with standard ECEC, food is not only served and eaten in the ECEC with sensory-based food education, but also is perceived as a way of pedagogy integration.

Questionnaire for the parents

Parents filled in a questionnaire on family background and the children’s Food Neophobia Scale (FNS), whose Finnish version focuses on children( Reference Mustonen and Tuorila 12 , Reference Pliner and Hobden 26 ). The FNS is a validated and widely used instrument measuring the respondent’s willingness to try novel and unfamiliar foods. Parents rated their level of agreement with their children’s behaviour for ten statements, for example ‘My child doesn’t trust new foods’, on a 7-point Likert scale where 1=‘strongly disagree’ and 7=‘strongly agree’. We combined the scale items (in part reverse-coded) to arrive at a food neophobia score ranging from 10 to 70; higher scores indicated higher food neophobia.

Snack buffet method

We developed an innovative approach, also known as the snack buffet method, for measuring children’s food choices in a naturalistic setting( Reference Hoppu, Prinz and Ojansivu 19 , Reference Bouhlal, Issanchou and Chabanet 32 ). During the development process, we took basic taste characteristics and the consumption of items in Finland into consideration to make sure we included both familiar and unfamiliar food items in the buffet. The buffet consisted of eleven vegetables, berries and fruit with a wide variety of flavours (pickled cucumber, green olives, lingonberry, grapefruit, blackcurrant, apple, honeydew melon, banana, cherry tomato, tinned champignon mushrooms, kohlrabi). The basic taste characteristics and profile of these items were preliminarily determined by sensory assessors at the University of Eastern Finland. The taste profiling was based on one session where the assessors were first asked to describe all perceived basic flavours and subsequently to indicate a dominant taste for each item. As a result of the profiling, the following dominant basic flavours were recognised: salty (pickled cucumber and green olives), sour and bitter (lingonberries and grapefruit), sour (blackcurrants), sweet and sour (apple), sweet (honeydew melon and banana), sweet and umami (cherry tomatoes), salty and umami (tinned champignon mushrooms), sweet and bitter (kohlrabi).

The buffet was served to the children at the ECEC centres during the regular snack time (14.00 hours). Full plates of vegetables, berries and fruit were placed on similar round porcelain serving dishes in the order listed above. We rinsed the pickled cucumbers, olives and tinned mushrooms, thawed the frozen lingonberries and blackcurrants, peeled and cut the grapefruit, honeydew melon and bananas into bitesize pieces, and cut the apples in bitesize pieces. A whole vegetable or fruit was placed next to each item that had been cut into pieces.

Children formed a line and one by one chose the items that they wanted from the buffet with assistance by the ECEC educators in spooning the food on their plates when necessary. The plates were replenished when needed. The educators instructed the children that they could have extra portions and did not have to eat everything. Early educators were advised neither to name the buffet items nor to encourage children to choose any particular items, and to behave similarly as during a regular afternoon snack. We used codes to refer to the children and their plates. We photographed( Reference Gemming, Utter and Ni Mhurchu 33 ) the plates each time the children selected items from the buffet, before they emptied their leftovers in the waste bin, and once they had finished eating. Water was served to drink. The images of the snack buffet, taken with a Samsung PL 20 camera, were coded and categorised into selected items, leftovers and finished sets. The photographs were assessed by a single researcher trained on the matter. Reliability was assessed by having the single researcher assess all digital photographs independently on two occasions, which took place at least 2 months apart. In addition, a reliability testing was performed, involving a trained registered dietitian scoring a sample of the photographs. This testing resulted in a consistency of 98·9 % for willingness to choose and 94·0 % for willingness to eat.

The children participated in the snack buffet once, on average in groups of ten, each session lasting approximately 30 min. The snack buffet was piloted during spring 2013 and found to function well in practice.

After the snack buffet, the children were offered their regular afternoon snack, which typically contained porridge/yoghurt/berry or fruit soup, bread and margarine, skimmed milk and fresh fruit or vegetable. We noticed a slight difference in the afternoon snack menus between the centres: the SEN ECEC centres regularly served fresh fruit or vegetables on a daily basis whereas the REF ECEC centres did so once or twice per week.

Variables

The two main variables of the study were ‘willingness to choose’ and ‘willingness to eat’. These were formed based on the photographs by analysing what the children had chosen and eaten, item by item. The former was a sum of the portions chosen, assessed as 0=‘none’, 1=‘one or little’ and 2=‘two or more’; the latter was a sum of the portions eaten, assessed as 0=‘took none’, 1=‘took some but ate none’, 2=‘ate half’ and 3=‘ate most or all’. One portion or a little portion was considered to include one bitesize piece of vegetable or fruit or a teaspoonful of berries, and two or more portions were considered to include at least two bitesize pieces of vegetable or fruit and more than a teaspoonful of berries.

For the analysis, we also included the following variables: sensory-based food education (SEN, REF), maternal education level (low, high), children’s food neophobia (continuous variable), children’s age (continuous variable, years) and gender (boy, girl). Maternal education level was dichotomised as low (primary education, vocational college or upper secondary education) or high (education in a university of applied sciences or university).

Statistical analysis

Associations with willingness to choose and willingness to eat were analysed using linear mixed-effects models. This method was used due to statistical dependencies among the children within the ECEC centres and child groups in the data. Dependencies on two levels were discovered in the present study. First, children socially influence each other in ECEC groups; and second, their work is framed by the practices, staff and facilities of the ECEC centre. The linear mixed-effects model analysis method allowed us to take these dependencies into account. The model consists of a systematic and a random part. The systematic part in the model assimilates to a regression model where observation units must be independent. The random part in our linear mixed-effects models takes account of the dependencies among children in the ECEC centres and child groups within each centre.

The response y of child k in group j within the ECEC centre i was analysed using the linear mixed-effects model as follows:

where

![]() $$x'_{{ijk}} \,\beta $$

is the systematic part of the model, u

i

and v

ij

are normally distributed,

$$x'_{{ijk}} \,\beta $$

is the systematic part of the model, u

i

and v

ij

are normally distributed,

![]() $$u_{i} \,\sim\,N(0,\sigma _{{{\mathop{\rm ECEC}\nolimits} }}^{2} )$$

and

$$u_{i} \,\sim\,N(0,\sigma _{{{\mathop{\rm ECEC}\nolimits} }}^{2} )$$

and

![]() $$v_{{ij}} \,\sim N(0,\sigma _{{{\rm child \,group}}}^{2} )$$

, random effects and child groups are nested within centres, and e

ijk

is a zero-mean residual error with constant variance.

$$v_{{ij}} \,\sim N(0,\sigma _{{{\rm child \,group}}}^{2} )$$

, random effects and child groups are nested within centres, and e

ijk

is a zero-mean residual error with constant variance.

In our willingness-to-choose model, statistically significant interactions were found between sensory-based food education and maternal education, and between sensory-based food education and average food neophobia in the SEN and REF groups. Consequently, the systematic part

![]() $$x'_{{ijk}} \beta $$

of the model included sensory-based food education, maternal education level, interactions between the food education and maternal education level and children’s food neophobia, the children’s age and gender, as well as the average food neophobia of the SEN and REF groups of children.

$$x'_{{ijk}} \beta $$

of the model included sensory-based food education, maternal education level, interactions between the food education and maternal education level and children’s food neophobia, the children’s age and gender, as well as the average food neophobia of the SEN and REF groups of children.

In our willingness-to-eat model, a statistically significant interaction was found between sensory-based food education and maternal education. Therefore, the systematic part

![]() $$x'_{{ijk}} \beta $$

included sensory-based food education, maternal education level, the interaction between the food education and maternal education level, and the children’s food neophobia, age and gender.

$$x'_{{ijk}} \beta $$

included sensory-based food education, maternal education level, the interaction between the food education and maternal education level, and the children’s food neophobia, age and gender.

We performed mixed-effects model analyses using R version 3.2.5 and its nlme package( Reference Pinheiro, Bates and DebRoy 34 ). We based model checking on visual inspection of different residual plots, and diagnostic plots on random effects.

Results

Children’s choices and eating from the snack buffet

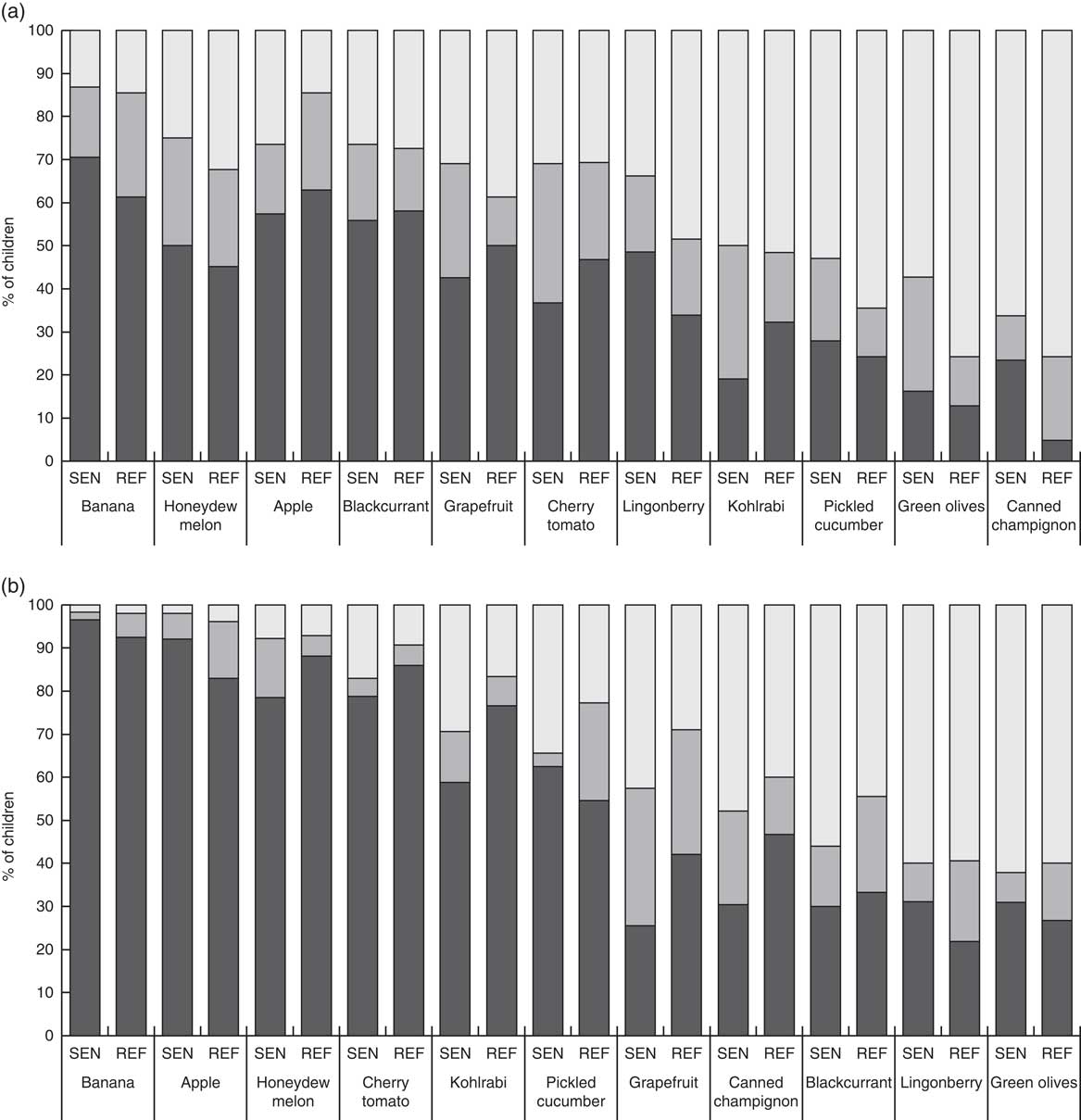

From the snack buffet, the children chose 6·9 (sd 2·9) items in the SEN group and 6·3 (sd 2·6) items in the REF group. Out of these selected items, the children consumed at least half, 4·8 (sd 2·4) items in the SEN group and 4·9 (sd 2·2) in the REF group. Children most commonly chose sweet and sour items from the buffet: bananas, apples, blackcurrants and honeydew melon (Fig. 1(a)). Other commonly chosen items were sweet and umami-flavoured cherry tomatoes and sour and bitter grapefruit and lingonberries. Less than half of the children chose kohlrabi, pickled cucumber, green olives and tinned champignon mushrooms, rendering ‘salty’ the least popular basic taste.

Fig. 1 Vegetables, berries and fruit from the snack buffet that were (a) selected (![]() , two or more;

, two or more; ![]() , one or little;

, one or little; ![]() , none) and (b) eaten (

, none) and (b) eaten (![]() , ate most;

, ate most; ![]() , ate half;

, ate half; ![]() , ate none) by 3–5-year-old children (n 130) at early childhood education and care, Finland, 2014 and 2015 (SEN, sensory-based food education group; REF, reference group)

, ate none) by 3–5-year-old children (n 130) at early childhood education and care, Finland, 2014 and 2015 (SEN, sensory-based food education group; REF, reference group)

The most common items consumed from the buffet were the sweet-flavoured bananas, apples, honeydew melon and cherry tomatoes (Fig. 1(b)). Overall, items with sour, bitter and salty taste were eaten the least.

The comparison between selected (Fig. 1(a)) and eaten (Fig. 1(b)) items shows an interesting trend in the children’s choices. Although blackcurrants and lingonberries were fairly common choices, less than half ate them in considerable amounts. On the other hand, kohlrabi and pickled cucumber were selected by less than half of the children but eaten to a greater extent by those who chose them.

Associations between sensory-based food education and willingness to choose and eat

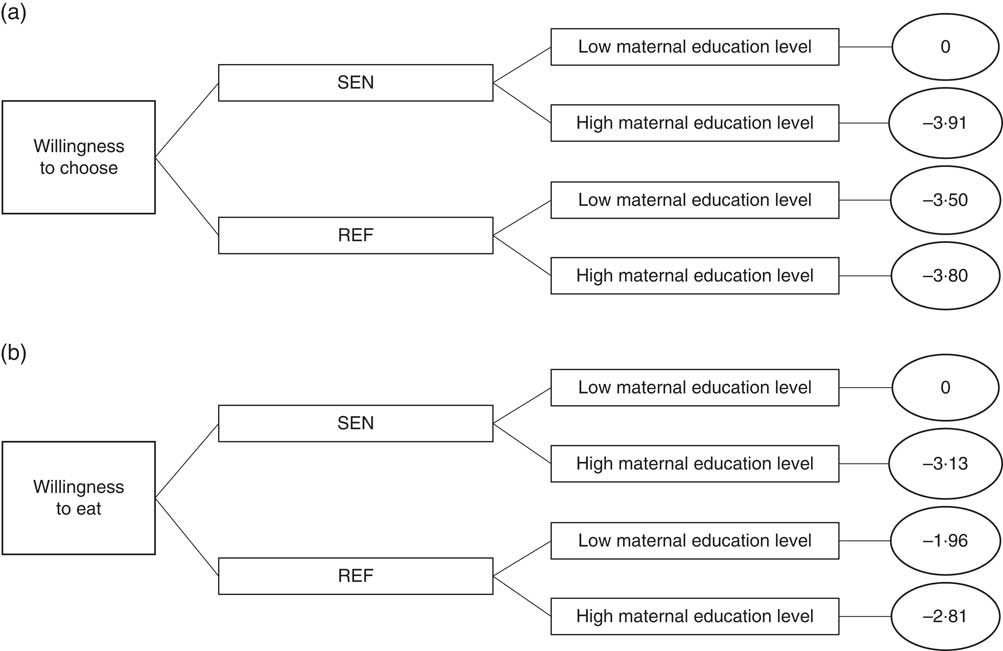

The highest willingness to choose was found among the children in the SEN group whose mothers had a low education level. Sensory-based food education had a positive association with willingness to choose. This association was stronger among children of mothers with a low education level (Fig. 2(a)).

Fig. 2 Interaction between sensory-based food education and maternal education in linear mixed-effects models for (a) willingness to choose and (b) willingness to eat vegetables, berries and fruit from a snack buffet among 3–5-year-old children (n 130) at early childhood education and care, Finland, 2014 and 2015. Values presented in ellipses are regression coefficients (SEN, sensory-based food education group; REF, reference group)

A significant interaction was found between sensory-based food education and maternal education (Table 3, Fig. 2(a)). In the SEN group, high maternal education decreased children’s willingness to choose (Fig. 2(a), β=−3·91, adjusted for group neophobia). By contrast, among the REF children, no similar effect of maternal education level was found, and the decrease caused by maternal education level was non-significant (Fig. 2(a), β=−3·50 for low and β=−3·80 for high maternal education level).

Table 3 Linear mixed-effects models of willingness to choose and willingness to eat vegetables, berries and fruit from a snack buffet in 3–5-year-old children (n 130) at early childhood education and care, Finland, 2014 and 2015

SEN, sensory-based food education group; REF, reference group.

Significant P values are indicated in bold font.

* Adjusted for food neophobia.

† Less than a university degree v. a university degree.

The highest willingness to eat was found among the children in the SEN group whose mothers had a low education level (Fig. 2(b)). Sensory-based food education had no statistically significant link to willingness to eat, but there was a positive tendency when we included it in the model (Table 3).

Sensory-based food education and maternal education also interacted with willingness to eat (Table 3, Fig. 2(b)). Among the children in the SEN group, high maternal education level decreased the children’s willingness to eat (Fig. 2(b), β=−3·13). By contrast, in the REF group, the decrease caused by maternal education level was non-significant (Fig. 2(b), β=−1·96 for low and β=−2·81 for high maternal education level).

Children’s food neophobia significantly predicted both willingness to choose (β=−0·09, P=0·002) and willingness to eat (β=−0·15, P<0·001; Table 3). The associations between gender and willingness were non-significant.

There was variation between ECEC centres and between child groups within the ECEC centres. The model’s standard deviations were as follows. For willingness to choose, the sd was 1·86 between ECEC centres and 1·37 between child groups in the centres. For willingness to eat, the sd was 0.0007 between ECEC centres and 2·47 between the groups of children in these centres.

Average neophobia in the groups of children and their willingness to choose

There was significant interaction between sensory-based food education and children’s average group neophobia with their willingness to choose (Table 3). Interestingly, the average food neophobia of the groups of children in the present study, especially the REF ones, affected their willingness to choose (β=−0·03, P=0·816 for SEN and β=−0·38, P=0·068 for REF). In other words, in our REF group of children, willingness to choose decreased as average group neophobia increased. In the SEN group, no such association was found. However, no similar effect could be found in connection with the willingness to eat.

Discussion

The present results showed that sensory-based food education implemented in ECEC was associated with children’s willingness to choose vegetables, berries and fruit; this association was stronger among children of mothers with a low education level.

The study also found that the group neophobia of the children in the REF ECEC towards vegetables, berries and fruit seemed to play a role in children’s willingness to choose these food items. Interestingly, the sensory-based food education in ECEC appeared to intervene in this group neophobia by diminishing its influence. At the same time, in individual children, food neophobia had a negative association with the willingness to choose and eat vegetables, berries and fruit.

Benefits of sensory-based food education

The current study has a twofold contribution to the increasing scientific evidence for the effectiveness of sensory activities in facilitating the introduction of health-promoting foods to children’s diets. First, sensory-based food education can play a role in reducing health inequity among children; and second, positive effects of such food education can also emerge at the group level.

Our findings support the hypothesis that sensory-based food education, integrated into the ECEC routine, promotes children’s willingness to choose vegetables, berries and fruit, but only with the children of mothers with a low level of education. Our results also mirror previous sensory education studies that have mostly concentrated on school-aged children. In Finland, sensory education has been shown to encourage children to taste unfamiliar foods( Reference Mustonen, Rantanen and Tuorila 10 ) and improve children’s skills in describing their food perceptions( Reference Mustonen and Tuorila 12 ). A Dutch school programme, Taste Lessons, implementing sensory food education at schools, was found to produce minor positive effects on children’s willingness to taste vegetables( Reference Battjes-Fries, Haveman-Nies and Renes 15 ), although these disappeared in further method evaluation using objective taste test measures( Reference Battjes-Fries, Haveman-Nies and Zeinstra 16 ). In France, taste sessions at schools increased children’s willingness to choose vegetables, but this effect was only temporary( Reference Reverdy, Chesnel and Schlich 14 ). In Finland the positive effects of sensory education occurred mainly among younger schoolchildren, which encourages implementing such activities with even younger children in ECEC( Reference Mustonen, Rantanen and Tuorila 10 ). In the context of under-school-aged children, a Finnish intervention study( Reference Hoppu, Prinz and Ojansivu 19 ) explored the impact of sensory-based food education focused on vegetables and berries, and found that such food education increased children’s willingness to eat these food items. Similarly, in the UK, non-taste sensory activities( Reference Dazeley and Houston-Price 18 ) and sensory play( Reference Coulthard and Sealy 17 ) with vegetables and fruit in ECEC increased children’s willingness to taste them.

Our results indicate that children of mothers with a low education level might benefit more from sensory-based food education. It is somewhat surprising and different from our hypothesis that lower socio-economic status would increase children’s willingness to choose and eat vegetables, berries and fruit in the sensory-based food education group in the present study. Families with low socio-economic status have been found to consume less vegetables, berries and fruit( Reference Fernandez-Alvira, Bornhorst and Bammann 20 ), and are therefore less likely to provide them to children at home( Reference Lehto, Ray and te Velde 35 ), which reduces their children’s familiarity with these foods( Reference Cook, O’Reilly and DeRosa 36 ). It is not clear why children from lower socio-economic families chose vegetables, berries and fruit more willingly. Earlier findings indicate that high-quality ECEC might be more beneficial for children from families with a lower socio-economic status compared with their peers with a higher socio-economic status( Reference Sylva, Melhuish and Sammons 37 ). It is possible that children of mothers with lower education levels benefit more from sensory-based food education than children of mothers with higher education. More highly educated mothers are probably more aware of healthy eating for children and offer a wider variety of vegetables and fruit at home( Reference Fernandez-Alvira, Bornhorst and Bammann 20 , Reference Lehto, Ray and te Velde 35 ).

Children’s individual food neophobia came as no surprise, and was a factor reducing both the children’s willingness to choose vegetables, berries and fruit as well as their willingness to eat them. This finding is consistent with our hypothesis and previous research showing a negative association between food neophobia and vegetable intake( Reference Cooke, Wardle and Gibson 38 – Reference Johnson, Davies and Boles 40 ).

However, no individual association between sensory-based food education and neophobia existed, although sensory lessons have been shown to reduce neophobia in Finnish( Reference Mustonen and Tuorila 12 ), French( Reference Reverdy, Chesnel and Schlich 14 ) and Korean( Reference Park and Cho 41 , Reference Woo and Lee 42 ) school-aged children.

Children’s group neophobia decreased their willingness to choose. In the reference group, the average level of neophobia reduced the children’s willingness to choose vegetables, berries and fruit. By contrast, the sensory-based food education group showed no similar tendency. This result supports previous findings that positive peer modelling increases novel food consumption( Reference Greenhalgh, Dowey and Horne 43 , Reference Birch 44 ) and that peer modelling can also reduce food neophobia( Reference Laureati, Bergamaschi and Pagliarini 45 ) with school-aged children. Therefore, one benefit of sensory-based food education could be the enhancement of a positive atmosphere in children’s groups in relation to food. This is in line with a Swedish study( Reference Sepp and Hoijer 46 ) which noted that ECEC children learn from and with each other also in relation to food.

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to assess sensory-based food education implemented by ECEC centres themselves and its association with children’s willingness to choose and eat vegetables, berries and fruit. It is important to study the factors associated with young children’s vegetable, berry and fruit choices and food education at ECEC, as diets adopted in childhood are likely to persist into adolescence( Reference Kelder, Perry and Klepp 47 ) and adulthood( Reference Wadhera, Phillips and Wilkie 48 ), and food education in ECEC can have long-term benefits to children’s health.

The snack buffet method is a new assessment tool which allows measuring young children’s willingness to choose and eat vegetables, berries and fruit in a naturalistic setting. Other strengths of the method include enabling both children and parents to work as informants, and the presence of a reference group. Furthermore, as a novelty, the current study examined food neophobia at the child group level and found this to be positively influenced by food education.

The study has three main limitations that may weaken the generalisability of the findings. First, obtaining all necessary information about the implementation of sensory-based food education in each ECEC centre turned out to be difficult. To get a more detailed picture about this topic, we explored existing documents and asked early educators for more information about related practices, facilities and tools. Second, our data lack information about children’s food preferences. However, according to earlier research, the vegetable and berry choices and eating habits of under-school-aged children appear to correlate weakly with their parents’ predictions about their child’s preferences( Reference Hoppu, Prinz and Ojansivu 19 ). Third, minor weaknesses in the arrangements of the snack buffet and coding of the photographs might have affected our results. As the method is developed further, the number of items served could be further considered to avoid misrecognition; the order of the positions of the items could rotate, or the items served could be placed on a round table to remove the emphasis on items that are placed in the first position. As sensory properties, such as shape and colour, affect children’s choices( Reference Dinnella, Morizet and Masi 49 ), they should be taken into account when reconsidering the included items. Furthermore, some challenges may concern the coding of photographs and the photographs should, therefore, be assessed individually by two trained researchers. Despite these limitations, our experience suggests that the snack buffet provides a child-oriented and promising method for assessing young children’s willingness to choose and eat vegetables, berries and fruit.

Practical implications

The study suggests that children whose mothers have a low level of education may benefit from sensory-based food education in ECEC and encourages wider introduction of the method to ECEC centres. This interesting finding concerning food education and low maternal education consolidates early educators’ role as food educators in promoting a diverse diet. We thus recommend sensory-based food education as a method for enhancing nutritional equality among under-school-aged children.

Sensory-based food education can be useful for increasing positivity towards food and eating as well as decreasing the effect of food-neophobic individuals in a group. In future research, when observing the effects of food education on children, more focus should be put on changes at the child group level. There is a need for further research determining the most effective sensory activities in promoting children’s vegetable, berry and fruit intake.

Conclusion

In conclusion, sensory-based food education is a promising and child-oriented method for promoting children’s adoption of vegetables, berries and fruit in their diets.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors are grateful to the ECEC centres, children and their parents for participating the study. They thank Anja Lapveteläinen ja Hely Tuorila for mentoring and Eliisa Wulff for proofreading. Financial support: This work was supported by the Jenny and Antti Wihuri Foundation. The Wihuri Foundation had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: K.K. had an important role in formulating the research questions, designing the study, carrying it out, analysing the data and writing the article. A.R. had an important role in formulating the research questions and writing the article. M.H. had an important role in analysing the data. A.L. had an important role in formulating the research questions and designing the study. O.N. had an important role in formulating the research questions, designing the study and writing the article. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the University of Eastern Finland Committee of Research Ethics. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.