In Malaysia, a high prevalence of diet-related health problems, namely obesity(1–Reference Zainuddin, Manickam and Baharudin4) and disordered eating(Reference Soo, Shariff and Taib5–Reference Gan, Mohamad and Law9), has been reported. The prevalence of obesity in Malaysian adolescents increased dramatically between the years 2011 and 2015 from 6·1 %(1) to 11·9 %(2) according to the National Health and Morbidity Survey. Disordered eating can be defined as unhealthy eating and weight-related behaviours and attitudes that are of medical and/or psychological concern, however cannot be considered as eating disorders(Reference Ackard and Legato10). The term ‘disordered eating’ is also used to describe dieting and unhealthy weight-loss behaviours(Reference Bryla11). The prevalence of disordered eating, which includes dieting, bulimia and food preoccupation, oral control, restrained eating and binge eating behaviours, is high in Malaysian adolescents, in the range of 14·0–36·0 % in various samples nationwide(Reference Soo, Shariff and Taib5–Reference Gan, Mohamad and Law9). This phenomenon becomes more alarming since the risk of disordered eating was found to be higher in overweight and obese adolescents than in non-overweight and non-obese adolescents(Reference Herpertz-Dahlmann, Wille and Holling12–Reference Norhayati, Chin and Mohd Nasir16). Poor eating behaviours among adolescents, such as skipping breakfast, as well as high consumption of fast foods and sweetened beverages can lead to these diet-related problems(Reference Nurul-Fadhilah, Teo and Huybrechts17–Reference Haines, Kleinman and Rifas-Shiman22).

Short- and long-term effects of eating behaviours were shown in several studies(Reference Bowman, Gortmaker and Ebbeling19,Reference Duffey, Gordon-Larsen and Jacobs20,Reference Bowman and Vinyard23–Reference Pedersen, Holstein and Flachs26) . Eating behaviours such as frequent eating at fast-food restaurants was found to be related to lower intakes of fruits, non-starchy vegetables, milk and key micronutrients in a sample of children, adolescents and adults(Reference Bowman, Gortmaker and Ebbeling19,Reference Duffey, Gordon-Larsen and Jacobs20,Reference Bowman and Vinyard23) , consequently being less likely to meet fruit and vegetable recommendations(Reference Welch, McNaughton and Hunter24). Moreover, eating behaviour in adolescence was shown to predict eating behaviour in adulthood(Reference Merten, Williams and Shriver25,Reference Pedersen, Holstein and Flachs26) .

Healthy eating during adolescence is essential since nutritious foods are important to support their rapid physical growth and development(Reference Adesina, Peterside and Anochie27,Reference Savige, Macfarlane and Ball28) . Insufficient intake of nutrients such as carbohydrate, protein, fat, vitamins and minerals may affect adolescents’ growth, sexual maturation and function(Reference Savige, Macfarlane and Ball28). On the other hand, excessive intake of foods may have negative effects on health by increasing susceptibility to non-communicable diseases(Reference Adesina, Peterside and Anochie27). Moreover, adolescents’ eating habits are changing rapidly and they are commonly involved in unstructured eating habits with more meals eaten outside the home, more foods consumed outside usual mealtimes, greater peer influence and more variation in intakes over time, with high levels of restrained eating(Reference Livingstone, Robson and Wallace29,Reference Pérez-Rodrigo, Artiach Escauriaza and Artiach Escauriaza30) .

In Malaysia, recommendations on healthy eating specifically for children and adolescents are included in the Malaysian Dietary Guidelines for Children and Adolescents(31). Based on the guidelines, children and adolescents are encouraged to eat fruits and vegetables, consume milk and milk products, and drink plenty of water daily. They are also encouraged to limit intakes of fat, salt and sugar in the daily diet, as well as to be physically active every day. Even though the guidelines are present, the food intakes of children and adolescents still do not meet the recommended amounts(Reference Woon, Chin and Kaartina32–Reference Pon, Kandiah and Mohd Nasir35).

The correct perception and knowledge on healthy eating is key to healthy eating behaviours in adolescents. However, previous intervention studies were shown to significantly change the nutrition knowledge, but not to change the nutrition practices or behaviours of participants(Reference Cown, Grossman and Giraudo36–Reference Ruzita, Wan Azdie and Ismail38). This may happen due to the interventions being based on declarative knowledge (i.e. the knowledge of ‘what is’, awareness of things and processes) rather than procedural knowledge (i.e. the knowledge about how to do things)(Reference Worsley39). Another possible reason may be that participants tended to perceive more barriers instead of facilitators for healthy eating. Thus, adolescents’ perceptions of barriers and facilitators for healthy eating should be explored to guide researchers to plan an appropriate intervention in order to enable adolescents to practise healthy eating. To the best of our knowledge, there is a lack of studies in Malaysia which explore the concepts of healthy eating, as well as the barriers and facilitators for dietary behaviour change, in adolescents.

The present study aimed to explore the concepts of healthy eating and to identify the barriers and facilitators for dietary behaviour change in Malaysian adolescents. Focus group discussion was chosen as the method of data collection since this method is suitable to obtain knowledge, perspectives and attitudes of the adolescents about the issue of interest and seek explanations for behaviours in a way that would be less easily accessible in responses to direct questions(Reference Krueger40,Reference Kitzinger41) .

The present study was a needs assessment as a part of the development of ‘Eat Right, Be Positive about Your Body and Live Actively’ (EPaL), a health education intervention to prevent overweight and disordered eating among Malaysian adolescents. The outcome of the present study guided the development of the content and activities for the EPaL intervention. The details of the EPaL intervention programme are reported elsewhere(Reference Sharif Ishak, Chin and Mohd Taib42).

Methods

Participants

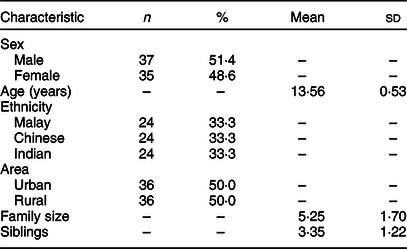

Participants for the focus groups were recruited from two secondary schools in the urban and rural area of Selangor, Malaysia. These two schools were randomly selected from thirty-six national secondary schools (Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan) in the district of Hulu Langat, in the state of Selangor, Malaysia. These schools were drawn from the list of schools which was obtained from the website of the Department of Education of Selangor(43). The schools that met the inclusion criteria (coeducational, multiracial, non-residential and non-religious) were eligible to be included in the draw. The inclusion criteria for the participants in the study were adolescents who were studying in Forms 1 or 2 and aged 13–14 years; and adolescents who were given consent by their parents to participate in the focus groups. A total of seventy-two adolescents participated in the present study. The sample consisted of about equal numbers of males (51·4 %) and females (48·6 %). Based on ethnicity, there were equal numbers of Malay, Chinese and Indian participants (each n 24, 33·3 %). Sociodemographic characteristics of participants in the focus group discussions are presented in Table 1. Permission for data collection in schools was obtained from the Ministry of Education of Malaysia, as well as the State Department of Education of Selangor. Consent was also obtained from the board of the school, the principal, the parents and the adolescents prior to data collection.

Table 1 Sociodemographic characteristics of participants in the focus group discussions: adolescents aged 13–14 years (n 72) from two secondary schools in the district of Hulu Langat in Selangor state, Malaysia, July and August 2013

Focus groups

A total of twelve focus groups were conducted in the present study, with six participants in each group. Focus groups were conducted during school hours in a room provided by the schools, and the participants were interviewed separately in the respective groups according to their age, sex and ethnicity. In each group, the focus group was conducted by a moderator and assisted by an assistant moderator who took field notes throughout the discussion. The discussion was conducted in Malay, Chinese and Tamil languages by different moderators and assistant moderators, respectively, according to the ethnicity of the group members and it followed the procedures in the Facilitator’s Guides booklet, which was prepared by the research team. All moderators and assistant moderators were trained by the research team to conduct focus groups prior to data collection. The data collection was conducted until it reached saturation point, where similar comments were consistently repeated and no new inputs were gained from the discussions.

Before each focus group discussion started, the moderator and assistant moderator introduced themselves to the participants and started the ice-breaking session in which each participant was asked to briefly introduce themselves. Then, the focus group discussion proceeded with the introduction to the study where the moderator briefly explained the aims of the focus group, the ground rules in the focus group and the confidentiality of the outcomes from the focus group. The participants were also informed that the discussion would be recorded using two voice recorders and the recording would be used later to guide the research team in tracing the voices of each participant for the transcription process of the focus groups. After the introduction, the discussion session began with semi-structured and open-ended questions from the moderator. Each focus group took about 60–90 min. The key questions for the focus group were:

1. What does the term ‘healthy eating’ mean to you?

2. What foods do you see as ‘healthy foods’?

3. What foods do you see as ‘unhealthy foods’?

4. What things encourage you to change your eating habits?

5. What things prevent you to change your eating habits?

Data analysis

The data analysis for focus group discussions was carried out by using thematic analysis, as described by Braun and Clarke(Reference Braun and Clarke44). First of all, the verbal data from the focus group discussions were transcribed verbatim while referring to the field notes that were taken by the assistant moderator. Moderators and assistant moderators then discussed and recorded their observation of the group, including content, non-verbal expression and communication between the group members. Data familiarisation was achieved by repeated reading of the transcripts and listening to the audio recordings. The focus group discussion transcripts were analysed by systematically coding the data underneath the main discussion topics, in order to permit main themes for every discussion topic to emerge. Connected codes were then collated into potential themes, and repeatedly reviewed and refined to confirm they mirrored the coded extracts and data set as a whole. The agreed themes were checked to confirm there were clear distinctions, and thereafter the final themes were named and defined. Acceptable extracts from the focus group discussions were chosen and agreed upon to support the ultimate themes.

Results

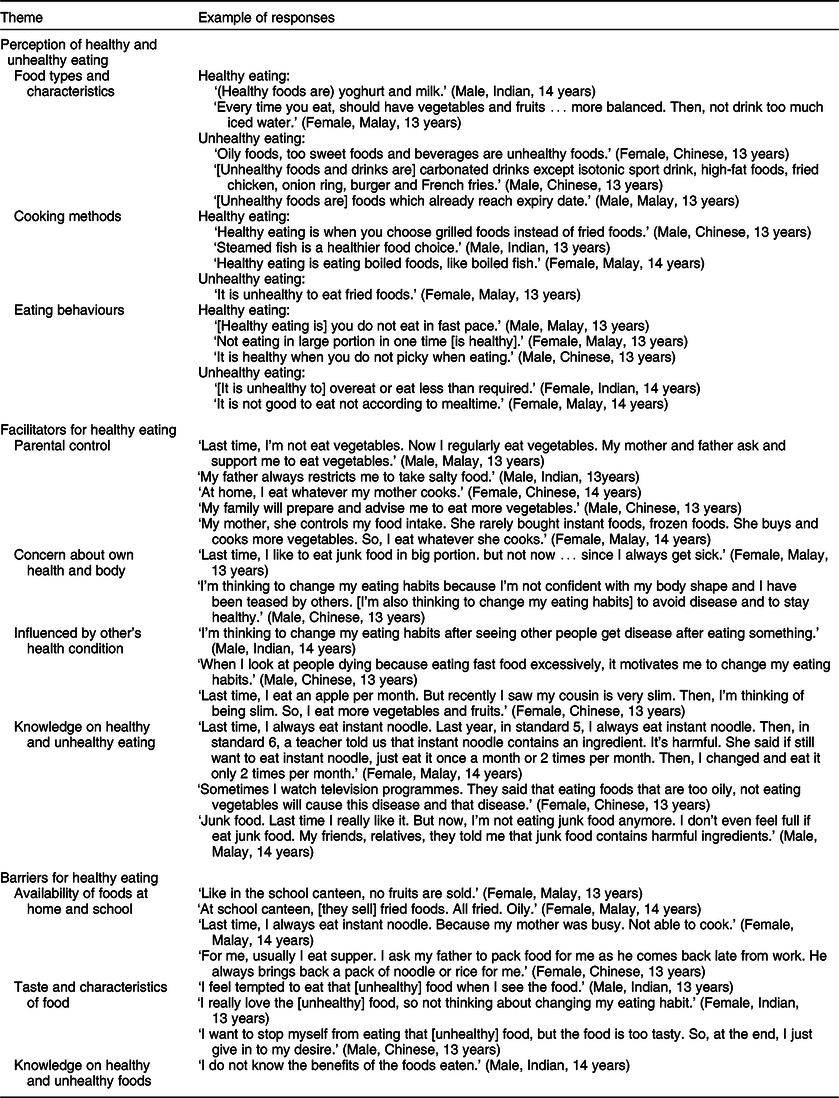

The outcomes from the focus group discussions are reported under three main headings: (i) perceptions of healthy and unhealthy eating; (ii) facilitators for healthy eating; and (iii) barriers for healthy eating. The themes and examples of responses are shown in Table 2.

Table 2 Perception of healthy and unhealthy eating, and facilitators and barriers for practising healthy eating, arising in the twelve focus group discussions among adolescents aged 13–14 years (n 72) from two secondary schools in the district of Hulu Langat in Selangor state, Malaysia, July and August 2013

Perceptions of healthy and unhealthy eating

Under this category, three themes arose: food types and characteristics, cooking methods and eating behaviours.

In terms of food types and characteristics, healthy eating was described by most participants by naming specific foods and food groups, such as fruits including fruit juice, vegetables like salad, green vegetables and garlic. They also mentioned cereals and cereal products such as oats, bread, wholegrain bread, rice, brown rice, dried noodle, meehoon (rice vermicelli), Tiger™ biscuits and Koko Krunch™ ready-to-eat cereal as healthy foods. Besides that, they also named milk and dairy products such as cheese, Dutch Lady™ and yoghurt as healthy foods. Soups were also mentioned as healthy foods, for example clear soup noodle, vegetable soup, mushroom soup and tomyam soup. Protein sources such as fish, meat, chicken and salmon, and dietary supplements like honey and bird’s nest were also included as their preference for healthy foods. They also mentioned plain water, vitamins, fresh foods, organic foods, sandwiches and fried rice as healthy foods. However, consuming foods based on the food pyramid was rarely mentioned by the adolescents.

On the other hand, adolescents named numerous foods which they considered unhealthy foods. They mentioned sweet foods and drinks like sweets, ice cream, chocolate, carbonated drinks, canned drinks and jelly as unhealthy foods. Fried, oily and fatty foods such as nasi lemak, fried chicken, onion rings, French fries, fried noodle, fried rice, murtabak and mayonnaise were also indicated as unhealthy foods. Moreover, they indicated fast foods like burger, instant noodle, pizza, nugget and sausage; processed foods like junk foods and canned foods like canned sardine; and food-taste enhancers like monosodium glutamate and pickles as unhealthy foods. Other food types including seafood, bah kut teh, sate, laksa, cheese, nasi ayam and popcorn were also mentioned by the adolescents as unhealthy foods. Based on food characteristics, they described unhealthy foods as ‘high-cholesterol food’, ‘high-protein food’, ‘food containing seasoning’, ‘food containing colouring’, ‘sambal-based food’, ‘spicy food’ and ‘expired food’.

In terms of cooking methods, steamed foods like steamed fish and steamed egg, grilled foods, barbecued foods, roasted foods like roasted chicken, boiled foods, non-fried foods and cholesterol-free foods were mentioned as healthy foods. Meanwhile, fried foods were mentioned as unhealthy foods.

Finally, based on eating behaviours, healthy eating was indicated as having three meals daily, eating at mealtime, not skipping meals and not eating late at night. Some adolescents mentioned that ‘eat until full enough’, ‘not eat in fast pace’ and ‘chew well’ as healthy eating. They also indicated healthy eating as ‘control food intake’, ‘balanced diet’ and ‘not picky when eating’. Furthermore, they related healthy eating with the concepts of moderation, for example ‘not eat large portion in one time’ and ‘not eat too much’. Besides that, ‘eat light taste food’ and ‘eat different dishes’ were also mentioned as healthy eating. On the other hand, unhealthy eating was indicated as not eating according to mealtime, drinking too much water, overeating or eating less, eating too much seafood and consuming food away from home.

Facilitators for healthy eating

Parents’ control on adolescents’ food choices was mentioned by most adolescents as a facilitator for healthy eating. Some adolescents mentioned that requests from teachers, relatives, coach and doctor to change their eating habits to healthier eating habits also facilitated them in healthy eating. The feeling of concern about their own health and body also facilitated them to eat more healthily. Their dissatisfaction about their health and physical appearance such as they felt like ‘getting fat’, ‘growing pimples’, ‘not confident with own body shape’, ‘get health problem’ and ‘always getting sick’ were considered by the adolescents a result of unhealthy eating behaviours. They practised healthier eating since they ‘want to stay healthy’, ‘to avoid diseases’, ‘to keep body fit’ and ‘to have a long life’. Moreover, they tended to eat healthier because they were ‘afraid of being fat’, ‘want to be taller’, ‘want to be thinner’, ‘concern about body size and shape’ and ‘do not want to wear spectacles’.

Some of them tended to change their eating behaviours to healthier eating habits after being influenced by other’s health conditions, for example they have seen other people fall sick or die because of excessive consumption of fast foods. Some of them also tended to eat healthier after being influenced by someone who has a slim body or seeing other people practising healthy eating.

Knowledge on healthy or unhealthy eating also contributed to facilitating the adolescents for healthy eating. The adolescents mentioned that they tended to practise healthier eating after knowing the effects of unhealthy foods and being aware that certain foods are unhealthy. The adolescents pointed out that they got the knowledge on foods that cause or prevent diseases from television programmes. Some of them got the knowledge from their teachers, such as instant noodle contains unhealthy ingredients which are harmful to health, carbonated drink is harmful to the intestine and fish has a high content of protein. Parents also became a source of their knowledge, in which parents told them that junk foods contain lots of monosodium glutamate, which is not good for the brain. Some of them got the knowledge from their friends and relatives, for example the fact that junk foods contain unhealthy ingredients.

Barriers to healthy eating

The adolescents named availability of food at home and school as the common barrier for practising healthy eating. At home, they have to consume what their parents prepared for them regardless if the food was healthy or not so healthy. On the other hand, the availability of unhealthy food choices was greater than that of healthy foods either in the school compound or outside the school.

The other barrier for healthy eating was taste and characteristics of foods. They said that the taste of healthy foods such as vegetables is ‘bitter’ and ‘not tasty’, and that the texture of green vegetables after being cooked is not attractive. It contrasted to unhealthy foods, which usually have good taste. The adolescents described that unhealthy foods and beverages are tasty, which they ‘cannot get rid of it’, increase their ‘temptation to eat’ and they ‘really like the food’. They also mentioned that they tended to follow their siblings in consuming unhealthy foods. Knowledge on healthy or unhealthy foods was also considered as barrier for healthy eating, as they mentioned that they were unable to practise healthy eating due to the lack of awareness on healthy eating and did not know the benefits of the foods.

Discussion

In the present study, adolescents had some understanding of the concept of healthy eating. Frequently, the adolescents described healthy and unhealthy eating based on food types and characteristics, by naming specific foods and food groups(Reference Croll, Neumark-Sztainer and Story45,Reference Frerichs, Intolubbe-Chmil and Brittin46) . Similar to several previous studies, fruits and vegetables were prominently mentioned as healthy foods by the adolescents(Reference Croll, Neumark-Sztainer and Story45,Reference O’Dea47) . Several previous studies with children(Reference Frerichs, Intolubbe-Chmil and Brittin46,Reference Sylvetsky, Hennink and Comeau48) and adults(Reference Povey, Conner and Sparks49) have also shown the same outcomes, as these foods have qualities such as being ‘fresh’ or ‘nutritious’(Reference Frerichs, Intolubbe-Chmil and Brittin46).

Similar to children, the adolescents always conceptualised unhealthy foods in relation to the foods’ taste, texture and visual appeal(Reference Frerichs, Intolubbe-Chmil and Brittin46). In a previous study(Reference Croll, Neumark-Sztainer and Story45), chips, candy, fast foods and soda pop were considered by adolescents as unhealthy foods, as well as pizza, sugary foods, butter/oils, junk foods, hamburgers and McDonald’s™. Other studies have shown that children(Reference Frerichs, Intolubbe-Chmil and Brittin46,Reference Sylvetsky, Hennink and Comeau48) and adults(Reference Povey, Conner and Sparks49) also considered fast foods, fried foods and sweet foods as unhealthy foods. In our study, the adolescents also mentioned that processed and canned foods, as well as food taste enhancers as unhealthy foods, similar to a previous study(Reference Povey, Conner and Sparks49). The adolescents also defined healthy eating based on the exclusion of unhealthy foods(Reference Stevenson, Doherty and Barnett50). Moreover, the adolescents were able to relate cooking methods in differentiating healthy and unhealthy foods, as well as relating healthy eating with the concept of balance and moderation(Reference Povey, Conner and Sparks49,Reference Dixey, Sahota and Atwal51) .

In the present study, some adolescents mentioned seafood and high-protein foods as unhealthy foods. They elaborated that they have experienced allergic symptoms when consuming seafood or they have seen others experience allergic symptoms due to seafood consumption. Even though fish and shellfish represent a valuable source of protein for the general population, these foods are known to induce hypersensitivity reactions in sensitised or allergic individuals(Reference Fernandes, Costa and Oliveira52). Moreover, in our study, fried rice was named as both a healthy and an unhealthy food. The adolescents may have considered fried rice as healthy because fried rice is usually prepared with the inclusion of vegetables and a protein source, such as chicken. Hence, it can be considered a balanced dish. On the other hand, fried rice was considered an unhealthy food because frying is considered an unhealthy cooking method(31).

Parents’ control on adolescents’ food choices was mentioned by most adolescents as a facilitator for healthy eating, consistent with a previous study(Reference Frerichs, Intolubbe-Chmil and Brittin46). An adolescent is influenced most heavily by parents and other family members and is exposed to the foods, activities and perceptions of obesity supported by the family in the home environment(Reference Brown, Shaibu and Maruapula53), whereby they adapt to and eat whatever their parents decide(Reference O’Dea47,Reference Monge-Rojas, Garita and Sanchez54) . Parental concern about adolescents’ weight was shown to impact on the availability of healthy foods at home. It was shown to be associated with less home availability of energy-dense snack foods like cakes, potato chips and sweets, and a lower intake of these food items among adolescents(Reference MacFarlane, Crawford and Worsley55). Furthermore, the availability of healthy foods was positively associated with diet quality and inversely related to BMI(Reference Tabbakh and Freeland-Graves56).

These findings document the potential of the home as a setting to promote positive dietary behaviours in adolescents. Additionally, the home food environment was shown to be more significant than the school food environment in predicting the dietary patterns among children from twelve countries(Reference Vepsäläinen, Mikkilä and Erkkola57). Since mothers were usually reported to be responsible for the preparation of family meals(Reference Rathi, Riddell and Worsley58,Reference Berge, MacLehose and Larson59) , maternal knowledge on nutrition could give positive effects in improving the quality of food intake and eating behaviour of adolescents at home. Proficient knowledge on nutrition appeared to be linked to a healthier home environment and enhanced diet quality. Mothers with greater knowledge on nutrition provided a healthier home environment, provided more healthy foods and made unhealthy foods less available in the home, which in turn improved the diet quality of adolescents(Reference Tabbakh and Freeland-Graves56).

The adolescents in our study were also willing to engage in healthy eating behaviours as a result of the feeling of dissatisfaction with their own health or physical appearance. A previous study(Reference Stevenson, Doherty and Barnett50) found a stronger link between the willingness to engage in healthy eating behaviours and the perception of weight and attitudes to weight-control behaviours, rather than concerns about short-term or long-term health. Health consciousness was found to have a positive, significant impact on substituting buying intentions, for instance substituting less healthy snack alternatives such as sweets and chips with healthier ones based on fresh fruits and vegetables(Reference Nørgaard, Sørensen and Grunert60).

The correct way to maintain a healthy body weight through healthy eating should be emphasised in health education among adolescents since weight concern was shown to have a direct association with weight-related problems, such as purging, binge eating and overweight(Reference Haines, Kleinman and Rifas-Shiman61). Several longitudinal studies also demonstrated that body dissatisfaction predicts the development of disordered eating behaviours in adolescents(Reference Stice62,Reference Wertheim, Koerner and Paxton63) .

Knowledge on healthy or unhealthy foods is also important to facilitate adolescents in practising healthy eating. This shows that having information about diet and nutrition is very crucial in adolescents because it is considered an important tool for knowing how to choose better foods(Reference Monge-Rojas, Garita and Sanchez54,Reference Molaison, Connell and Stuff64) . The knowledge among adolescents is of concern, as dietary practices established at this stage in life may persist in subsequent years(Reference Pedersen, Holstein and Flachs26).

Perceived barriers to healthy eating have been shown to fully mediate the relationship between self-efficacy and fruit and vegetable consumption(Reference Bruening, Kubik and Kenyon65). In the present study, the adolescents mentioned availability of foods at school as a barrier for them to practise healthy eating. In school, it seems common to find that there is a higher availability of unhealthy food choices compared with healthy foods(Reference Croll, Neumark-Sztainer and Story45,Reference O’Dea47,Reference Monge-Rojas, Garita and Sanchez54,Reference Rathi, Riddell and Worsley66) . In Malaysia, there is a guideline for food and drink sales in the school cafeteria and any location within the school compound, which lists the foods and drinks that can be sold at school, as well as the foods and drinks prohibited and not recommended to be sold in schools. However, there are still many school cafeterias that do not adhere to the guideline.

Targeting perceived barriers to healthy eating such as the lack of availability, as well as affordable and appealing healthy foods in schools may serve to increase adolescents’ willingness and ability to incorporate recommendations into their lifestyles(Reference Croll, Neumark-Sztainer and Story45). Besides home, school eating was shown to be associated with better food choices than other locations(Reference Ziauddeen, Page and Penney67). The availability of healthy foods can increase the consumption of healthy foods, as shown in previous studies whereby adolescents believed that if fruits or vegetables were more readily available in their environment, such as in vending machines at school or on the table at home, they would be more likely to consume them(Reference Kubik, Lytle and Hannan68,Reference Di Noia and Contento69) . Efforts are needed not only to increase the availability and accessibility of healthful foods, but also to educate children on appropriate food choices within and among food groups, as well as to provide youths with nutrition education and behavioural skills training to encourage greater consumption of these foods(Reference Condon, Crepinsek and Fox70). There are limitations for adolescents to apply their nutrition knowledge into practice due to low confidence in food skills. Even though they are very interested in developing food skills such as food preparation, they had very limited opportunities due to the lack of food literacy education in home and school settings(Reference Ronto, Ball and Pendergast71). Future intervention could emphasise skill-based nutrition education since it has great potential in improving eating behaviours and food skills(Reference Hartmann, Dohle and Siegrist72,Reference Price, Carrington and Margheim73) .

The adolescents also related healthy eating with the taste and characteristics of foods, in a negative view, consistent with several studies(Reference Croll, Neumark-Sztainer and Story45,Reference O’Dea47,Reference Sylvetsky, Hennink and Comeau48,Reference Stevenson, Doherty and Barnett50,Reference Monge-Rojas, Garita and Sanchez54,Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Story and Perry74) . This shows that food aesthetics, in terms of taste, texture, appearance and smell, is one of the most powerful physical reinforcers of food choices(Reference Stevenson, Doherty and Barnett50,Reference Rasmussen, Krølner and Klepp75) . Similar to previous studies, it seemed difficult to eat as recommended because of the better taste of unhealthy foods than more healthful options(Reference O’Dea47,Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Story and Perry74) , as well as the satiety and craving of ‘less healthful’ alternatives(Reference O’Dea47).

The way foods are prepared or served also influences food choices among adolescents(Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Story and Perry74). Changes in preparation methods or improvements in the presentation of fruits and vegetables could make these items more appealing to children(Reference Condon, Crepinsek and Fox70). Food preparation was shown to be important for children’s and adolescents’ acceptance of vegetables, for example they preferred boiled vegetables over baked and stir-fried vegetables of the same colour(Reference Molaison, Connell and Stuff64,Reference Poelman and Delahunty76) . In addition, a study also showed that adolescents had high acceptance of snack products based on fresh fruits and vegetables(Reference Nørgaard, Sørensen and Grunert60).

The strength of the present study is its focus on adolescents and the inputs which came from adolescents from three main ethnicities in Malaysia (Malay, Chinese and Indian), both in the urban and rural area. To our knowledge, the present study is the first using a qualitative method, specifically focus group discussions, to explore the adolescents’ perceptions on healthy eating, as well as the facilitators and barriers for practising healthy eating in the Malaysian setting. As for the limitations of the study, the adolescents may have given socially desirable responses during the focus group discussions, especially when they could not prompt their personal barriers or if they overstated their positive healthy eating behaviours. Moreover, the present study was carried out among school adolescents in the district of Hulu Langat, Selangor. Thus, the study results cannot be generalised to all adolescents from other schools in Selangor or other states in Malaysia. The results also cannot be generalised to adolescents who are not studying in formal education.

Conclusions

The findings of the present study contribute to a better understanding of the adolescents’ perceptions of healthy eating, as well as the facilitators and barriers to practising healthy eating in Malaysia. Overall, even though the adolescents had the correct concepts on healthy eating, which guided their existing knowledge, the higher perceived barriers may inhibit them from practising healthy eating. This is the gap that researchers should take into account in developing interventions to promote a healthy lifestyle among adolescents. Instead of only providing the adolescents with relevant knowledge, they should be educated on coping with the barriers around them in order to make healthy lifestyle a reality. Future interventions should include a method of promoting the immediate benefits of healthy eating to enhance the importance of healthy eating in the eyes of adolescents. In addition, the intervention should also emphasise increasing the availability of healthy food choices at home and in the school environment. Apart from educating the adolescents, health and nutrition education programmes should also provide knowledge and guidance towards healthy eating for their parents. This is because adolescents are looking to their parents to encourage, support and enable them to be involved in more healthful behaviours. As mentioned earlier, the results of the present study were used in the development of the content and activities of the EPaL intervention programme.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors sincerely thank the schools, teachers and students who participated in this study. They are also grateful for the support and cooperation received from the Department of Education of Selangor and the Ministry of Education of Malaysia. Financial support: This study was financially supported by a grant offered by the Ministry of Higher Education of Malaysia under the Exploratory Research Grant Scheme (ERGS) (grant number 5527042). The Ministry of Higher Education of Malaysia had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: S.I.Z.S.I., C.Y.S., M.N.M.T. and Z.M.S. contributed to the conception and design of the study. C.Y.S. led the project and secured the necessary funds. S.I.Z.S.I. carried out the study, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. C.Y.S., M.N.M.T. and Z.M.S. contributed to drafting the manuscript and provided critical input. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the Ethics Committee for Research Involving Human Subjects of Universiti Putra Malaysia, Selangor, Malaysia (reference UPM/TNCPI/RMC/1.4.18.1(JKEUPM)/F2). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.