Spanish accounts confirm that at the time of the sixteenth-century entrada, turkeys and turkey husbandry were a prominent part of the Rio Grande Puebloan economic and ceremonial way of life (Schroeder Reference Schroeder and Ortiz1979:236–252). However, by the seventeenth century, domesticated turkeys virtually vanished due to the Spanish encomienda, or tithing system, which placed heavy demands on already strained Native maize and clothing (manta) resources. At the same time, the repartimiento system exploited Native labor for the production and export of cotton and woolen textiles to New Spain (Hackett Reference Hackett1937:120; Kessell Reference Kessell2008:83–84; Scholes Reference Scholes1937:106, Reference Scholes1942:48; Snow Reference Snow and Weigle1983; Webster Reference Webster1997:493, Reference Webster and Potter2009:186–187, 203). The research questions addressed here are, Did Spanish demands for tribute and Native labor of the 1600s adversely impact a millennium of indigenous turkey husbandry and ceremonialism, so central to Pueblo identity and ancestral traditions? And how did Pueblo people collectively respond?

This article draws on genetic, archaeological, ethnographic, iconographic, and folklore evidence to argue that although Spanish tribute and Native labor demands disrupted Puebloan turkey husbandry, turkeys remained important to kachina ceremonialism and played a central role in Native narratives of resistance and revitalization during the Pueblo Revolt era (AD 1680–1692). A specific set of Indigenous narratives about Corn Maiden (aka Turkey Girl) and her turkey charges informed the revitalization movement and shaped pan-Pueblo identity during the post–Pueblo Revolt interregnum.

To support this claim, first, the article provides an overview of turkey husbandry as a gendered practice and its ritual/symbolic use and significance to Ancestral Puebloan people throughout the northern Southwest spanning the longue durée from Basketmaker II to Spanish colonization in the 1600s. Second, because Spanish demands on maize and Native labor depleted domestic turkey flocks, turkey feather artifacts important to kachina ceremonialism had to be reused, and turkey feather blankets used as burial shrouds were replaced by woolen blankets. Finally, in a subversive response, “Turkey Girl” (Persecuted Heroine type) tales attributed to allied Pueblo groups (Keres, Tewa, Zuni, Towa, Northern Tiwa) during the post–Pueblo Revolt period appropriated and repurposed one or more Spanish Christianized folktales as an expression of pan-Pueblo resistance to Spanish culture and revitalization.

Turkey Husbandry in the American Southwest

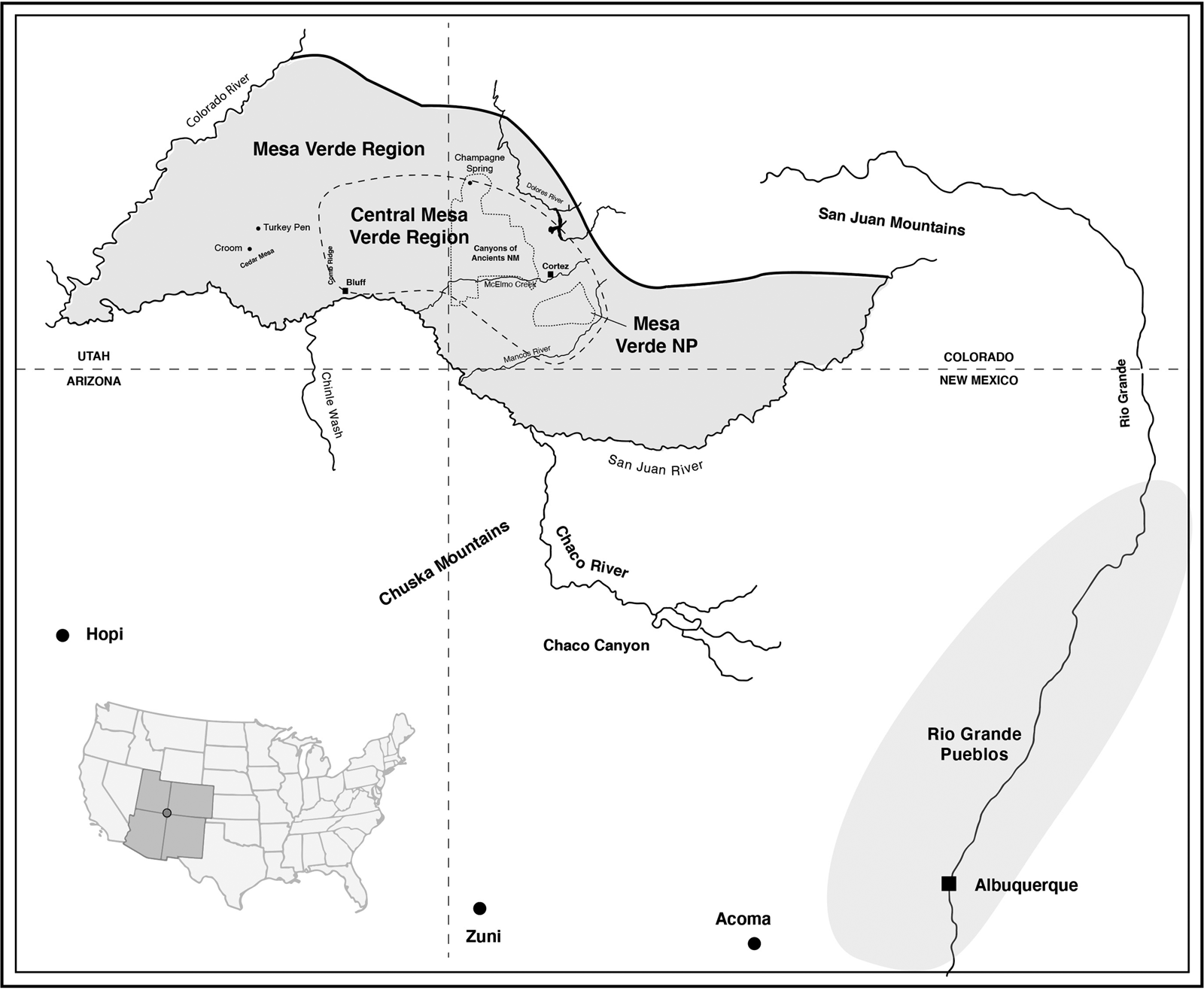

This section adopts the definition of Ancestral Puebloan turkey husbandry as the breeding, feeding, and management or penning of wild and domesticated turkeys in the American Southwest from a fairly broad perspective for the purpose of reviewing evidence reported at multiple sites in the northern San Juan and Rio Grande Valley (RGV; Figures 1 and 2) regions. First, this evidence supports the claim that turkey husbandry was a widespread and temporally continuous practice in the American Southwest spanning over a millennium beginning in Basketmaker II (500 BC–AD 500). Second, I discuss evidence suggesting that Ancestral Puebloan turkey husbandry was a gendered activity involving the women of the household.

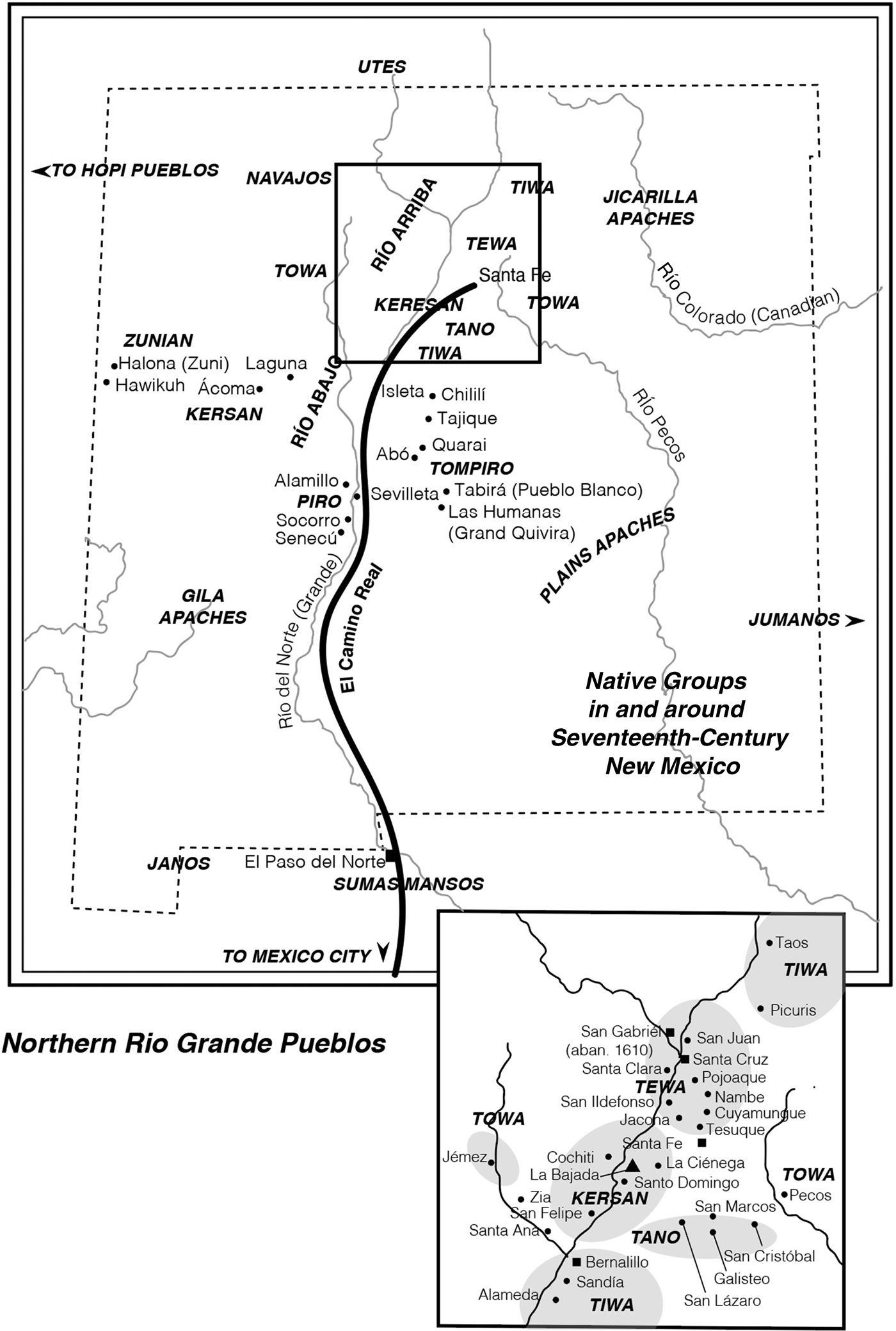

Figure 1. Map of the Mesa Verde, Chaco, and Rio Grande areas (after Lipe et al. Reference Lipe, R, Bocinsky, Chisholm, Lyle, Dove, Matson, Jarvis, Judd and Kemp2016:99, Figure 1; map by Corinne Idler).

Figure 2. Map of Rio Colorado Valley pueblos of the seventeenth century (after Kessell Reference Kessell2008:100, Figure 10; map by Corinne Idler).

Evidence of genetic uniformity of the turkeys within the Greater Southwest culture area for well over a millennium suggests that intensive breeding of a single population occurred through time (Speller et al. Reference Speller, Kemp, Wyatt, Monroe, Lipe, Arndt and Yang2010:2810). The predominance of a single haplotype (aHap1) also suggests control of hens during breeding season (Lipe et al. Reference Lipe, R, Bocinsky, Chisholm, Lyle, Dove, Matson, Jarvis, Judd and Kemp2016:106), although before AD 1050, they were not exploited as an important subsistence resource (Badenhorst and Driver Reference Badenhorst and Driver2009 and others). The wild progenitor of the domesticated turkey appears to have been introduced into the American Southwest through human-mediated exchange of domestic (or at least captive) birds from eastern (Meleagris gallopavo silvestris) and Rio Grande (Meleagris gallopavo intermedia) turkeys (Speller et al. Reference Speller, Kemp, Wyatt, Monroe, Lipe, Arndt and Yang2010:2807–2810). Speller and colleagues' (Reference Speller, Kemp, Wyatt, Monroe, Lipe, Arndt and Yang2010) genetic analysis of turkeys in North America and southern Mexico revealed rare cases of interbreeding between domesticated turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo intermedia; aHap1) and Merriam's indigenous turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo merriami; aHap2).

Despite the scarcity of evidence of interbreeding, domesticated and wild turkeys were often co-present and managed by Ancestral Puebloans throughout the northern Southwest from Basketmaker II to Pueblo III (AD 1300) and at Rio Grande Valley sites from AD 1200–1300 to the Pueblo Revolt era, AD 1680–1692 (Kemp et al. Reference Kemp, Judd, Monroe, Eerkens, Hilldorfer, Cordray, Schad, Reams, Ortman and Kohler2017; Speller et al. Reference Speller, Kemp, Wyatt, Monroe, Lipe, Arndt and Yang2010; also see Lipe et al. Reference Lipe, R, Bocinsky, Chisholm, Lyle, Dove, Matson, Jarvis, Judd and Kemp2016:100, 106). Recently, Conrad (Reference Conrad2021a) reported evidence (including caked droppings, eggshells, and feathers) of similar strategies used for turkey confinement over 1,600 years from Basketmaker II to the historic period. These strategies included creating penning spaces, reusing extant spaces, and individual bird management such as tethering.

At Basketmaker period sites, pens were created in rock shelters and caves, such as Pocket Cave, Broken Flute Cave, Painted Cave, Tseahatso, and Atlatl Cave (see references in Conrad Reference Conrad2021a) and habitation structures were reused as pens; for example, at Pictograph Cave in the Kayenta area. Later during Pueblo II–III, evidence of penning appears at Mesa Verde (Step House, Spruce House), Chaco Canyon (Pueblo Bonito, room 92; Spadefoot Toad, room 9), and Salmon Ruin (Conrad Reference Conrad and Crown2020, Reference Conrad2021a and references).

Publoans inhabiting large villages during Pueblo III–IV, adapted earlier turkey management practices by creating pens within plazas and rooms, reusing kivas and rooms for pens, and caging or tethering individual birds (Conrad Reference Conrad2021a). The greater RGV and southwest New Mexico region marks the eastern-southeastern edge of Southwest indigenous Merriam's turkeys habitat (see Speller et al. Reference Speller, Kemp, Wyatt, Monroe, Lipe, Arndt and Yang2010:2810, Figure 4). Genetic analysis of turkey bones identifies the mtDNA of domestic and wild turkeys at RGV sites predating AD 1280 (Kemp et al. Reference Kemp, Judd, Monroe, Eerkens, Hilldorfer, Cordray, Schad, Reams, Ortman and Kohler2017; Speller et al. Reference Speller, Kemp, Wyatt, Monroe, Lipe, Arndt and Yang2010). These sites include LA3333, approximately 32 km (20 miles) south of Santa Fe (AD 1170–1230); LA6169, close to Cochiti Pueblo (AD 1200–1280); and LA672 Forked Lightning, Pecos (AD 1175–1350, based on tree-ring data and pottery; Kemp et al. Reference Kemp, Judd, Monroe, Eerkens, Hilldorfer, Cordray, Schad, Reams, Ortman and Kohler2017:4–5, Table 1). The oldest level of LA4618 in Los Alamos (AD 1275–1325) slightly predates AD 1280 (Speller et al. Reference Speller, Kemp, Wyatt, Monroe, Lipe, Arndt and Yang2010:2809, Figure 3).

Stubbs and Stallings' (Reference Stubbs and Stallings1953) excavation of Pindi Pueblo (LA1) in the Santa Fe area revealed several phases of occupation with evidence of intensive turkey domestication (e.g., eggshell, turkey bone, caked droppings, turkey pens) as early as AD 1250–1270 (Post and Blinman Reference Post and Blinman2013). Pindi Pueblo plazas accommodated turkey pens in the form of “enclosures of small poles and twigs appended to the exterior walls of room blocks” (Post and Blinman Reference Post and Blinman2013). Evidence of turkey husbandry or perhaps trade in turkeys also appears at early post–AD 1280 sites such as Arroyo Hondo (LA12) and South Pueblo, Pecos (Kemp et al. Reference Kemp, Judd, Monroe, Eerkens, Hilldorfer, Cordray, Schad, Reams, Ortman and Kohler2017:4).

Whereas seventeenth-century Spanish records recount seeing hundreds of penned turkeys at various RGV pueblos (Schroeder Reference Schroeder and Ortiz1979:236–253), Conrad (Reference Conrad2021b) found a surprising paucity of turkey pens in the archaeological record for RGV Classic period (AD 1400–1600) pueblo sites. I propose that a possible explanation for this gap may be turkey imprinting behavior, which would likely make penning unnecessary in some cases. Studies in turkey behavior reveal how easily wild turkey hatchings and poults—unlike chickens and less so for ducks—imprint on human caregivers (Healy Reference Healy and Dickson1992:53–55; Hutto Reference Hutto2011), creating long-lasting social bonds with each other and with humans. Although turkey imprinting on human caregivers may not have impacted penning practices in all cases, the turkey-human potential for close bonding figures centrally in Pueblo “Turkey Girl” tales discussed below.

Women as Turkey Primary Caregivers

Gendered readings of the archaeological record in the American Southwest reveal the close relationship between turkey husbandry and women caregivers from Basketmaker II to historic times across the entire northern Southwest region. Cross-cultural ethnographic studies and recent research on turkey and human paleodiets support the idea that women were typically the primary caregivers of small mammals or birds, including domesticated turkeys (Lipe et al. Reference Lipe, R, Bocinsky, Chisholm, Lyle, Dove, Matson, Jarvis, Judd and Kemp2016; Rawlings Reference Rawlings2006; Rawlings and Driver Reference Rawlings and Driver2010; Szuter Reference Szuter and Crown2000).

Rawlings (Reference Rawlings2006:166; also Lipe et al. Reference Lipe, R, Bocinsky, Chisholm, Lyle, Dove, Matson, Jarvis, Judd and Kemp2016:105–106; Rawlings and Driver Reference Rawlings and Driver2010:2437) draws on ethnographic evidence to discern worldwide patterns associated with the care and feeding of small, household-based domestic animals. She concluded that women of the household had control over distributing maize and other plants and that they cooked and cleaned up after meals. Consequently, small mammals and birds fed from household stores of food and scraps from household meals were fed and cared for by the women of the house.

If turkeys were raised by women of the household, then we would expect to see proof of their being fed from domestic stores of food. Based on carbon and nitrogen isotopic analyses of pollen profiles from domesticated turkey coprolites at sites spanning 500 BC–AD 1150 in the northern San Juan area, researchers concluded that the diet of domesticated and free-riding wild turkeys was often similar to that of their human caretakers—that is, rich in maize, a C4 plant (see Conrad et al. Reference Conrad, Jones, Newsome and Schwartz2016; Lipe et al. Reference Lipe, R, Bocinsky, Chisholm, Lyle, Dove, Matson, Jarvis, Judd and Kemp2016:103, 104, Table 1; McCaffery et al. Reference McCaffery, Tykot, Gore and DeBoer2014, Reference McCaffery, Miller and Tykot2021; Rawlings Reference Rawlings2006:167, Table 38).

It is important to note that before turkeys were confined in pens in late Pueblo II, isotopic values of the remains of daytime free-ranging domesticated turkeys revealed a diet that incorporated C4 plants and animal protein, probably from insects and small lizards (Lipe et al. Reference Lipe, R, Bocinsky, Chisholm, Lyle, Dove, Matson, Jarvis, Judd and Kemp2016:105, Table 2). Jones and colleagues (Reference Jones, Conrad, Newsome, Kemp and Kocer2016) found one exception to this pattern in turkey paleodiet at Tijeras Pueblo, south of present-day Albuquerque, where maize farming was less reliable, resulting in turkey paleodiet of C3 plants. Despite the evidence of some domesticated turkeys having a somewhat diverse diet, the revelation of both wild free-riding and domesticated turkeys' dietary dependence on a maize-rich diet, in general—similar to that of their female caregivers and relations—provides some insight into Pueblo folktale narratives in which Turkey Girl, who apparently represents Corn Maiden, feeds her turkey charges and shares with them a close “kinship” relationship.

The Religious Significance of Turkeys to Pueblo People

Turkeys were valued ritually and symbolically for their feathers starting in the Basketmaker II period, only becoming a food source between AD 1050 and 1280, which is when Ancestral Pueblo populations in the Central Mesa Verde (CMV) area increased and subsequently decimated large game species (Badenhorst and Driver Reference Badenhorst and Driver2009; Lipe et al. Reference Lipe, R, Bocinsky, Chisholm, Lyle, Dove, Matson, Jarvis, Judd and Kemp2016:98). A large body of archaeological evidence encompassing the northern San Juan and Rio Grande Valley regions, in addition to cross-cultural ethnographic evidence, has increased our understanding of the reasons why turkeys were valued ritually and symbolically for over a millennium in the northern Southwest (Morris and Burgh Reference Morris and Burgh1954; Munro Reference Munro, Ubelaker and Sturtevant2006; Tyler Reference Tyler1979).

One class of material evidence pertains to the ritualized interments of complete turkeys from Basketmaker III to Pueblo III across the northern San Juan region. The Basketmaker III sites in southeast Utah and northeast Arizona include the Croom site (42SA3701 at Cedar Mesa [Matson et al. Reference Matson, Lipe and Haase1988, Reference Matson, Lipe and Haase1990]) and Tseahatso at Canyon de Chelly (Morris Reference Morris1939:18–19). Excavations at Champagne Spring (5DL2333), a Pueblo II–III site in southwest Colorado, report 70 ritualized interments of turkeys (Dove Reference Dove2012). Lipe and colleagues (Reference Lipe, R, Bocinsky, Chisholm, Lyle, Dove, Matson, Jarvis, Judd and Kemp2016:107–108), as well as others, hypothesized that the ritualized interments of poults and adult turkeys occurred in the spring during the planting season as prayers for rain and a bountiful corn crop.

A symbolic complex centered on turkeys, rain, and ancestors as rain beings is materially present at Chaco great house sites. Evidence of the ritual use of turkeys at Pueblo Bonito and Chacoan outlier sites suggests that turkey-rainmaking ideology and symbolism may have diffused to Pueblo Bonito (29SJ387) with migrants leaving northern San Juan villages between AD 875 and 925 (Wilshusen and Van Dyke Reference Wilshusen, Van Dyke and Lekson2006:237, 246–248). At Pueblo Bonito, evidence of ritualized turkey burials appears in rooms and kivas that are in the “Old Bonitian” north-central, ritually important section (Judd Reference Judd1954; Parsons Reference Parsons1939:29, note). Notably, turkey bones were identified in Kiva R (AD 860)—the place associated with the highest frequency of ceremonial offerings (Heitman Reference Heitman, Heitman and Plog2015:226–227, Table 8.4). In addition, Kristin Safi's (Reference Safi2015:439–453, Table D1) macroregional study of Chacoan great houses in the northern and southern San Juan regions during the Pueblo II period examined evidence of community-integrating activities related to feasting and ritual use of turkeys. Conrad (Reference Conrad2021a) discusses several sites with evidence of ritual turkey interments, for example Mesa Verde (Mug, Step, and Spruce Houses), Pueblo del Encierro in the RGV, the Zuni Village of the Great Kivas, Sapawe (Sapa'owingeh), on the Chama River, and others in the RGV as well as at Paquimé (Phase 1300s–1400s) in northern Mexico.

Based on material and ethnographic evidence, archaeologists interpret turkey interment practices in the context of a turkey symbolic complex composed of ancestors, prayers for rain/clouds, and maize agriculture. Tyler (Reference Tyler1979:93–94) notes that in historic and present-day Pueblo societies, turkeys are associated with the dead, who can become cloud spirits and bring rain (Lipe et al. Reference Lipe, R, Bocinsky, Chisholm, Lyle, Dove, Matson, Jarvis, Judd and Kemp2016:108; see Parsons Reference Parsons1939:275, 290). McKusick (Reference McKusick2001:43; also Riley Reference Riley1999:21, 65) maintains that this turkey-centered, rainmaking ideology is likely associated with a rainmaking kachina belief system involving the deity Tlaloc that diffused north from Mesoamerica (or perhaps northern Mexico). By the fourteenth century, clearly the turkey-feather symbolism had been integrated into kachina ritualism (Adams Reference Adams1991; Lekson and Cameron Reference Lekson and Cameron1995). As McNeil and Shaul (Reference McNeil and Shaul2018) posit, rainmaking ideology most likely diffused into southeast Utah and subsequently into the CMV area with southern Uto-Aztecan migrant farmers from the Sonora/Arizona borderland farming communities during the early Basketmaker II period.

A second class of material evidence, turkey-feather blankets or robes, supports the idea of a symbolic association between turkeys and the deceased. Twined turkey-feather cord was employed in the production of blankets or robes, which provided warmth over an individual's lifetime (Lipe et al. Reference Lipe, Shannon Tushingham, Blinman, Webster, LaRue, Oliver-Bozeman and Till2020) and served as a burial shroud in death, often for women and children (Osborne Reference Osborne2004; Parsons Reference Parsons1939:275, 29; Webster Reference Webster1997:715–739, Appendix G, Reference Webster, Drooker and Webster2000). Cross-cultural ethnographic evidence confirms women's privileged involvement in mortuary practices (Gligor and Soficaru Reference Gligor and Soficaru2018). Whereas Pueblo men wove cotton textiles for ceremonial use in a kiva on an upright loom, women produced turkey-feather blankets in the household setting on a frame (Lipe et al. Reference Lipe, Shannon Tushingham, Blinman, Webster, LaRue, Oliver-Bozeman and Till2020:Figures 1, 2–4, and Table 1; Osborne Reference Osborne2004:50, Figures 36–37; Webster Reference Webster and Potter2009:178, Figure 4.35) using the soft downy plume and semi-plume of turkey feathers.

Archaeological records confirm the presence of turkey-feather blankets dated from Basketmaker II to Pueblo II in the northern Southwest region and from late Pueblo II to the contact period in the RGV. Basketmaker II period turkey-feather blankets were recovered in funerary contexts at Grand Gulch in southeast Utah (Osborne Reference Osborne2004:49), Cedar Mesa (Guernsey and Kidder Reference Guernsey and Kidder1921; Kidder and Guernsey Reference Kidder and Guernsey1919:174–175; Lipe et al. Reference Lipe, Shannon Tushingham, Blinman, Webster, LaRue, Oliver-Bozeman and Till2020), Canyon del Muerto (Morris Reference Morris1939:18–19), and in the Prayer Rock District (Lukachukai Mountains; Morris Reference Morris1980:51–53, 111). Several excavations in the northern San Juan dated turkey-feather blankets to Basketmaker II–III: the Dolores Archaeological Project (DAP, Dolores River Valley), the Animas–LaPlata Project, the Navajo Reservoir Project in northwest New Mexico, and the Mesa Verde / Wetherill Mesa Project in southwest Colorado (Kane and Robinson Reference Allen E. and Robinson1988; Osborne Reference Osborne2004; Webster Reference Webster and Potter2009:125, Table 4.19).

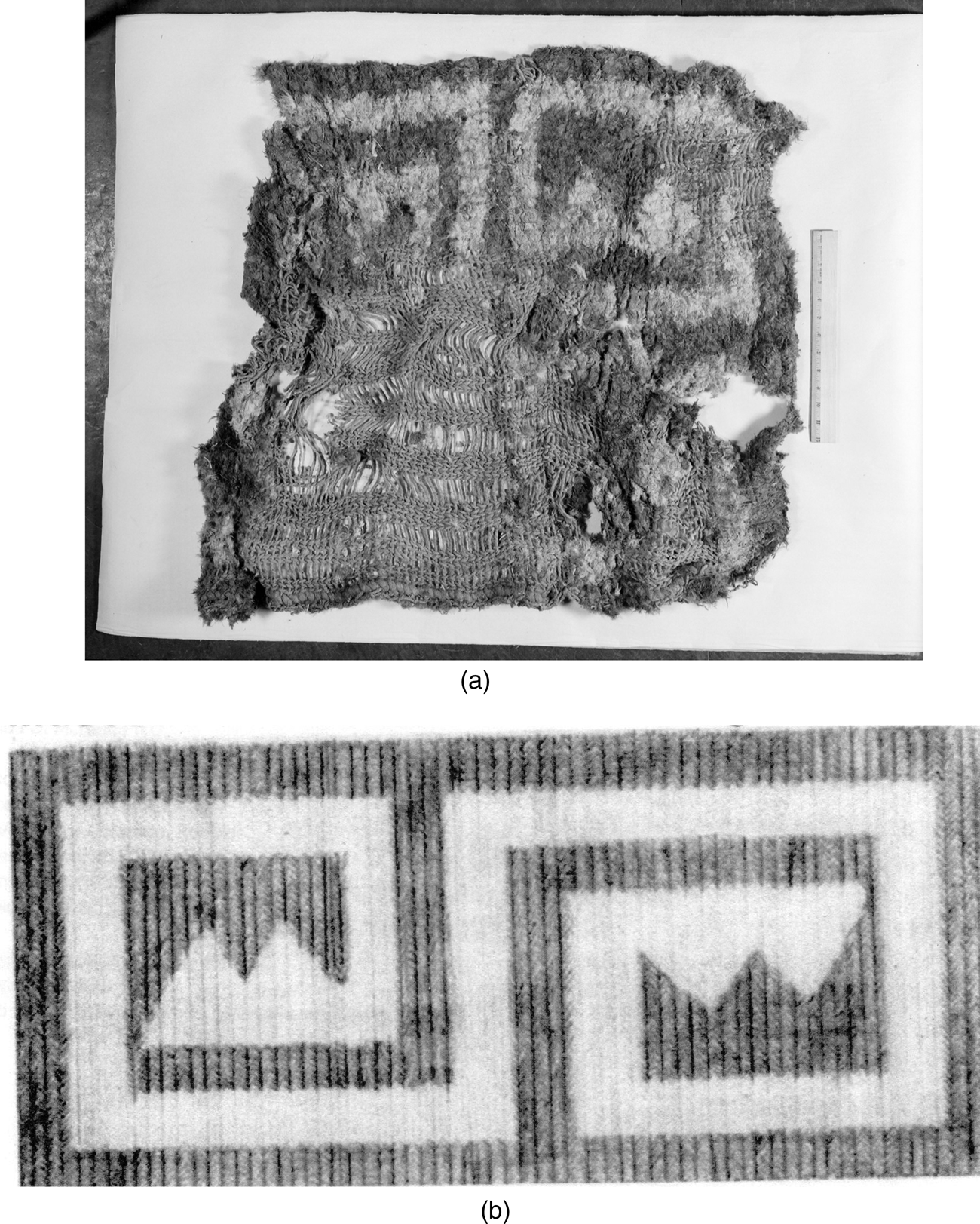

At Mesa Verde sites from AD 500 to 900, Osborne (Reference Osborne2004:22–24, 26, 29–33, 49–63) reports that 22 (out of 41) turkey-feather blankets functioned as burial wrappings for infants, subadults, and adults. Of these 22 burial shrouds, three were decorated blankets using tan or brown-and-white turkey feathers to create a variety of designs dated to the mid–AD 1200s. One Mesa Verde decorated blanket depicted an interlocking fret woven design (Osborne Reference Osborne2004:61, Figure 42), resembling McElmo and Mesa Verde Black-on-white pottery designs (Figure 3a and 3b). According to Laurie Webster (personal communication 2020), a turkey-feather blanket from Grand Gulch (AD 1200s) was decorated with a “grid” of white downy squares, similar to the dot-in-a-square motif (“corn kernels”) seen in late twelfth- or early thirteenth-century ritual clothing (Webster et al. Reference Webster, Hays-Gilpin and Schaafsma2006).

Figure 3. (a) Decorated turkey-feather blanket with pattern developed in light and dark down. Photo courtesy of Penn Museum, object # Wetherill B 1, no. 2; (b) reconstruction of the design woven into the blanket (Osborne Reference Osborne2004:61, Figure 42).

Regarding Pueblo Bonito around AD 875–925, Judd (Reference Judd1954) documented four “Older Bonitians” buried in (turkey) feather robes or blankets. In addition, there are numerous references in the Chaco online archive for the Hyde Expedition to yucca cord wrapped with feathers, which evidence suggests were turkey feathers. In the oldest crypt, room 33, one individual is buried with “fabrics” (possible cotton or feather cloth?); in adjacent room 53, the skull of a child was found with fragments of a feather blanket and the pieces of two cradles (Judd Reference Judd1954:339); and in adjoining room 56, a young woman was shrouded in a feather robe (Judd Reference Judd1954:339; Moorehead Reference Moorehead1906:34).

The National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) Smithsonian Institution Anthropology database lists Pueblo Bonito room 330, individual #15 as covered with a blanket made of feathers and rabbit skin in a mesh of yucca strings. This essentially describes a hybrid turkey-feather and rabbit fur blanket. Given that a few (n = 4) known Pueblo Bonito burials included turkey-feather shrouds—a practice similar to that reported in numerous Mesa Verde burials (Osborne Reference Osborne2004)—this raises the question of whether turkey-centered rainmaking ideology and ritual practices diffused by way of a trading network between Mesa Verde and Chaco Canyon, as I infer from Wilshusen and Van Dyke's (Reference Wilshusen, Van Dyke and Lekson2006:237, 240–242) research .

Webster (Reference Webster1997:715–739, Appendix G) lists sites in the Eastern Pueblo RGV area, where an abundance of turkey-feather blankets were identified mainly in burial contexts—evidence suggesting their ritual/symbolic significance. In chronological order, they include Pueblo III Pindi Pueblo (LA1), Pueblo IV Puye or Frijoles Canyon (Cave burial) and Arroyo Hondo; Pueblo IV–V Bandelier's Puaray (LA326), Kuana (LA187), and Tsankawi; and Pueblo V Jemez Cave (LA6164), Jemez Mountains (LA38962), and Unshagi (LA123). According to Webster (personal communication 2020), turkey-feather blankets fell out of use by the 1700s after the Pueblo Revolt, although the craft is being restored by women in the eastern Pueblos today.

Turkey Imagery on Painted Pottery and Rock Art

Given the evidence of the ritual and symbolic importance of turkeys to Ancestral Puebloans, it is unsurprising that turkey or turkey-track petroglyphs appear as early as Basketmaker II–III in the Bluff area of southeast Utah (Ann Phillips, personal communication 2021) and later in painted design elements on pottery at northern San Juan (i.e., Mesa Verde and Chaco) and at RGV sites by the 1300s.

Painted pottery from ritual contexts depicting turkey or turkey-track images is present at CMV, Chaco, Cibola/Mimbres, and RGV sites—the latter associated with Tewa and Keresan speakers. In DAP and nearby CMV area excavations at Sand Canyon and Hovenweep in southwest Colorado, several (n = 13) pots depict turkey tracks and four turkeys on rim sherds and an exterior surface. One turkey image appears on a kiva jar lid (Figure 4). Regarding Mesa Verde, Osborne (Reference Osborne2004) reports that decorated bowls with turkey images are deposited in ritual contexts. For example, a Mesa Verde Black-on-white bowl depicting five turkeys on its exterior with a dot-in-a-square “maize” and “rain lines” design on its interior (Figures 5a and 5b) was recovered from estufa (kiva) #238 at Spring (or Mug) House (Osborne Reference Osborne2004:562, no. 160). A pictograph of a turkey was depicted in a kiva at Long House, Mesa Verde. The concurrence of turkey imagery, vessel type (small bowl and jar), and mortuary depositional context suggests that turkeys—typically hens or prepubescent males (a few with “beards”)—represented a religiously important bird associated with rainmaking rituals for Mesa Verde people.

Figure 4. Mesa Verde Black-on-white kiva jar and turkey image painted on inside of lid, 1997.10.5MT765.V18, Sand Canyon Pueblo (5MT765). (Photo courtesy of Canyons of the Ancients Museum, Cortez, Colorado.) (Color online)

Figure 5. (a) Exterior of Mesa Verde Black-on-white bowl with five turkeys from Mug House, MVNM; (b) interior of same bowl. (Catalog # MEVE 19664, ACC 00703. Photo courtesy of Chapin Mesa Archaeological Museum, Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado.) (Color online)

Judd (Reference Judd1954:200, Figure 50B) provides a drawing of two turkeys eating a frog that are painted on the exterior of a bowl, possibly Mesa Verde Black-on-white, from Pueblo Bonito Kiva 2-E. Similarly, in room 266, Judd describes several bowls and small jars that are thought to be Mesa Verde imports (Judd Reference Judd1954:195; Wilshusen and Van Dyke Reference Wilshusen, Van Dyke and Lekson2006), with one bowl depicting a frog, associated with water, on the inside bottom (Judd Reference Judd1954:Plate 58[a]). The Chaco online database for the Hyde Expedition also lists a potsherd with turkey-track design from Pueblo Bonito (H/O3998) and a turkey effigy pot from Judd's (Reference Judd1954) Smithsonian report (NMNH cat. no. E410312-0).

Several Classic Mimbres bowls (AD 1000–1150) depict turkey images (n = 30) with anatomical traits including snood, wattle, and beard (Dolan Reference Dolan2021; Figure 6). Like their Chacoan and Mesa Verde contemporaries, Mimbres people apparently viewed turkeys, as well as macaws, as ritually symbolic birds. Lekson (Reference Lekson2008:237) posits that during Pueblo II (AD 900–1150) Mimbres middlemen transported Mesoamerican goods and ideas—in my view, rainmaking ideology—to Chaco elites by following inland routes to and from western Mexico and Aztatlan cities on the Pacific Coast. Located along the same longitudinal axis as Mimbres villages and Chaco sites (Lekson Reference Lekson2015; Minnis et al. Reference Minnis, Whalen, Kelley and Stewart1993), Medio period (AD 1200–1450) Paquimé in northern Mexico (Dean and Ravesloot Reference Dean, Ravesloot, Woosley and Ravesloot1993) confined turkeys and macaws in pens most likely for ceremonial purposes.

Figure 6. Classic Mimbres Black-on-white bowl (MA 10317): turkeys consuming centipede, AD 1000–1150. Ceramic, slip, and paint, 4⅛ × 10 × 9½ in. (Photo courtesy of the Dallas Museum of Art, Foundation for the Arts Collection, anonymous gift 1988.99.FA.) (Color online)

In contrast to utilitarian ware, Ancestral Puebloan painted pottery often encoded religious knowledge, and it was used in ritual contexts and deposited in kivas or burials. Whereas large decorated bowls were used in the context of communal feasting and exchanged among different communities, smaller (~10–12 cm) bowls were made to be kept, because they played a role in “constructing and maintaining social and ritual power” (Mills Reference Mills and Crown2000:308–309). Although ethnographic sources suggest that this class of objects was typically made by men (Bunzel Reference Bunzel1932; Parsons Reference Parsons1939), by late Pueblo III, potters' tool kits appear in mortuary contexts (Crotty Reference Crotty1983:30), all in female burials, which suggests that Pueblo women were potters then as they are today (Hays-Gilpin Reference Hays-Gilpin and Crown2000:104). Regarding who may have painted religious imagery on pottery, Hays-Gilpin (Reference Hays-Gilpin and Crown2000:104–105) maintains that women were permitted to paint religious imagery on pottery as Hopi women did in historic times, painting kachinas on pottery, and as Zuni women did (Bunzel Reference Bunzel1972) as a prayer offering—similar to men's turkey-feather prayer sticks. If one of women's roles in a household was as primary caregiver for domesticated turkeys, then it is reasonable to assume that women produced and decorated pottery with turkey or turkey-track imagery.

After settling in the RGV area in the early 1300s, Tewa-speaking migrants from Mesa Verde (Ortman Reference Ortman2012:8–9, Figure 1.2 from Mera Reference Mera1935) appear to have subsequently adapted the local Bandelier (Biscuit A) Black-on-white pottery (AD 1350–1450) to create a Biscuit B type (AD 1400–1540) by enlisting stylistic elements from Mesa Verde Black-on-white, such as rim ticking, interior and exterior banded designs, and—in rare known cases—turkey images important to Tewa religious beliefs as previously discussed.

From Chaco Red Mesa Black-on-white pottery, Mera (Reference Mera1935; see Ortman Reference Ortman2012:35) draws a direct descendant line of pottery types to Kwahe'e Black-on-white (AD 1050–1200) found at an early LA1 Pindi occupation site, followed in time by Santa Fe Black-on-white (AD 1175–1350) and Pindi Black-on-white (AD 1300–1425). The latter, depicting two facing turkeys, was found at Pindi (Tewa word for “turkey”) Pueblo, where turkey husbandry was well established (Supplemental Figures 1 and 2, Biscuit B and Pindi Black-on-white bowls). If Pindi Pueblo was actually founded by Keresan (not Tewa) speakers, as Eric Blinman proposes (personal communication 2020), then it is possible that they had an historic connection to Chaco. At the large Classic period site of Sapawe (Sapa’owingeh; AD 1300–1600) that is attributed to Tewa speakers, a Biscuit ware miniature pot with Mesa Verde style rim ticking depicts a turkey image on one side of its exterior and a fanned out turkey tail on the other (Maxwell Museum catalog #:66.105.52; UNM excavations at Sapawe 1964). It is thought to have been found in a burial context suggesting that it reflects a northern Southwest turkey-rainmaking ideology. Although beyond the scope of this article, it is worth mentioning in passing that, according to Shaul (Reference Shaul2014:141–143), the Keresan language served as a “prestige code” for Chacoan ceremonialism, which this study argues included turkey-centered rainmaking ideology.

From AD 1300 to 1540 in large, aggregated Rio Grande Valley towns, pottery styles and iconography cut across several media. According to Hays-Gilpin (Reference Hays-Gilpin and Crown2000:104), religious iconography—such as kachinas, macaws, cloud terraces, rainbows, and flowers—appears on pottery, rock art, and kiva murals. I would add to this list turkey imagery, which is often found in close proximity to Corn Maiden figures on pottery and rock art (Patterson-Rudolph Reference Patterson-Rudolph1997:8, Tables 2 and 9, Figure 4) and was conceptually integral to rainmaking ideology and proto-kachina ceremonialism.

Notably, rock art images of turkeys at Santa Fe Valley and Frijoles Canyon sites depict turkeys with diagnostic snood and/or wattle attributes (rarely with typically male “beard” or tail displays). All known RGV turkey images are stylistically similar to those depicted on Mesa Verde Black-on-white (Tewa); for example, Pindi Black-on-white (Keres?), and Bandelier Biscuit B Black-on-white (Tewa) bowls (see Supplemental Figures 1 and 2). On all of these bowls, turkey hens or prepubescent toms are stylistically similar—with elongated, boat-shaped bodies (sans tail display), arched heads with snood and/or wattle, turkey-track talons, and three or four feather tails. At Santa Fe Valley rock art sites, such as the La Cieneguilla Petroglyph site near Santa Fe and Petroglyph National Monument near Albuquerque, I have observed stylistically similar turkey and turkey-track rock art imagery at high-visibility sites appropriate for public viewing. In a few isolated cases, rock art sites are situated in low-visibility, perhaps ritually restricted venues such as the “Las Estrellas” site in Frijoles Canyon (Munson Reference Munson2002, Reference Munson, Wiseman, O'Laughlin and Snow2006), which dates to the post–Pueblo Revolt period, when remote refuge pueblos such as Tewa Nake'muu (LA12655) provided sanctuary.

Spanish Impact on Turkey Husbandry and Kachina Ceremonialism

The Spanish colonization system of taking tribute (encomienda) and exploiting labor (repartimiento) from Pueblo people adversely impacted their physical and cultural survival. In this section, I focus specifically on the impact of these systems on Native ceremonial practices, particularly those that relied intensively on maize and turkeys. Increasing assaults on Native culture and identity reached a climax in the 1660s with the “Kachina Wars,” when Spanish governors and Franciscan friars joined in an attempt to squelch the kachina religion by prohibiting dances and destroying ritual objects.

Established under governor Pedro de Peralta in 1609–1610, the Spanish system of tribute (or tithing) required one fanega (“bushel”) of maize and 1 m2, or vara, of cotton mantas (cloth for clothing) or one animal hide from each household per year. The number of seventeenth-century Pueblo households, or “tributary units,” was 4,000. If half of these units collected one Pueblo-woven manta per year, then the Pueblos supplied roughly 2,000 mantas annually to these outside consumers (Kessell Reference Kessell2008:84; Webster Reference Webster1997:185).

Spanish Impact on Turkey Husbandry

When various Spanish expeditions arrived in New Mexico over the course of the sixteenth century, many reported seeing Pueblo villages with large turkey herds and people wearing turkey-feather cloaks (Reed Reference Reed1951:199; see Schroeder Reference Schroeder and Ortiz1979:236–253 on Coronado [AD 1540–1542], Rodriguez-Chamuscado [AD 1581–1582], Espejo [AD 1582–1583], Castaño de Sosa [AD 1590–1591], and Oñate [AD 1598–] expeditions; Webster Reference Webster1997:90). Piros, southern Tiwas, Keres, Tanos, Ubates (Galisteo Basin), Tewas, and Zunis made turkey-feather blankets or robes; Piros and Keres raised turkeys for meat (Schroeder Reference Schroeder and Ortiz1979:236–250; Webster Reference Webster1997:81, 85); and eastern Tiwa and Tompiro pueblos raised turkeys mainly for their feathers (Bolton 1963:180).

Since the Early Agricultural Period, maize had been an essential part of the paleodiet of domesticated turkey and Ancestral Puebloan people (Lipe et al. Reference Lipe, R, Bocinsky, Chisholm, Lyle, Dove, Matson, Jarvis, Judd and Kemp2016; Rawlings and Driver Reference Rawlings and Driver2010). It is reasonable to assume that the size of household turkey flocks were greatly reduced due to poor maize crop yields resulting from the drought of the 1660s, a problem further exacerbated by maize tribute demands forced on Pueblo women. This, in turn, would result in a scarcity of turkey feathers for turkey-feather robes, burial shrouds, and kachina ceremonial objects (e.g., masks, prayer sticks). By the 1700s, turkey-feather blankets (robes/shrouds) were no longer in use, having been replaced by Spanish sheep wool—according to Webster (Reference Webster1997)—and turkey-feather ceremonial objects, refreshed with new feathers in the past, had to be reused (discussed below).

In addition to maize tribute, Spanish textile tribute in cotton mantas would also disrupt the supply of Native cotton ceremonial clothing (e.g., kilts, mantas, fringe belts), which was traditionally produced by Pueblo men on upright looms in kivas. Inquisition documents dating from the mid-1660s recount how missionaries exploited Pueblo labor for the production of textiles exported to New Spain (Hackett Reference Hackett1937:144). If Pueblo men were trying to meet the demands of textile tribute, this would impinge on time needed to farm maize, hunt, and weave cotton cloth for ceremonial purposes. During the 1660s, textile tribute negatively impacted Native household production of everyday and ceremonial clothing and blankets by enlisting men (upright looms) as well as women and children (spinning, knitting stockings).

The depletion of turkey flocks resulting from maize tithing and textile tribute demands on women's labor and time made it difficult to meet the ever-present need for new turkey-feather ceremonial objects and turkey-feather robes and shrouds. These perhaps unintended assaults on Pueblo culture and identity would devolve further during the 1660s into direct, coordinated attacks by Spanish civil and religious authorities on the kachina religion.

The Kachina Wars of the 1660s

Between 1630 and 1660, Spanish governors resisted the Franciscan mission attacks on native ceremonies—and even actively promoted them. They did so partly because they regarded Pueblo masked dances as harmless ceremonies akin to folk dances that were popular in seventeenth-century Europe and partly to reduce tensions with Pueblo people that might foment violence (Riley Reference Riley1999:91, 104–105, 156–157). By the late 1660s, however, they had allied with Franciscan friars to implement a concerted attack on Pueblo religious ceremonies—specifically masked dances, which lay at the core of Pueblo life.

From the beginning of missionization in the 1620s, Franciscans dressed in dark-blue habits in honor of the Blessed Virgin (Kessell Reference Kessell2008:98–100,109) and actively opposed the kachina religion. In 1625, the friars began the practice of cutting Indians' hair, ignorant of the fact that long hair had then (and now) great ceremonial importance to Pueblo people (Riley Reference Riley1999:96). In 1623, Fray Alonso de Benavides, custodian for the missions in New Mexico, intensified the mission agenda by using his Inquisitorial powers to characterize Pueblo ceremonialism as a form of witchcraft and demonology. In the 1640s and 1650s, Puebloan pushback against religious oppression resulted in public whippings of the rebel leaders, further driving Pueblo ceremonialism and resistance underground (Riley Reference Riley1999:72, 110–111, 130). Turkey Girl tales, discussed below, allude to these offenses.

In the late 1660s, the war against the kachina religion involved banning kachina dances and confiscating and destroying religious paraphernalia (e.g., feathered prayer sticks, masks, and ceremonial clothing; Riley Reference Riley1999:157). Natural disasters such as drought (AD 1659) and famine (AD 1667–1668) destroyed the land, desiccated the corn, and killed domesticated animals, including turkeys, all of which directly impacted kachina ceremonialism (Kessell Reference Kessell2008:104). In 1675, governor Juan Francisco Treviño and three advisors pressed to end the resurgence of Pueblo religion among the Tewas and outlying Taos (northern Tiwa), Acoma (Keres), and Zunis, but the friars were unable “to turn back the tide of idolatry” (Kessell Reference Kessell2008:110–111, 134). This conflict ended with the roundup of Tewa “sorcerers” and the confiscation of all ceremonial paraphernalia. In the early 1660s, Father Alonso de Posada banned any further kachina dances and ordered missionaries to destroy all seized Pueblo ceremonial artifacts, including masks, prayer sticks, and effigies. One thousand six hundred such objects, among them a dozen “diabolical” kachina masks from Isleta Pueblo, were burned at the friars' bidding (Kessell Reference Kessell2008:86–87, 98, 125; Scholes Reference Scholes1942).

Franciscan Conversion Efforts

Whereas on the one hand, Franciscan friars suppressed kachina ceremonialism, on the other, they disseminated Catholic dogma through iconographic and oral literature messaging, such as articles of faith pertaining to the venerated status of the Immaculate Virgin Mary, the Christ Child, and the Holy Family. Statues and paintings representing the Blessed Virgin Mary (BVM) testify to her widespread veneration among Franciscan friars in Old Spain and at missions in New Mexico (Kessell Reference Kessell2008:97–100). For example, La Conquistadora, a 1 m (3 ft.) high high wooden statue brought to Santa Fe, New Mexico, by Fray Benavides in 1626, was honored on the banner displayed by Don Diego de Vargas during his reconquest beginning in 1692. She also figures centrally in a Pueblo Revolt–era painting that juxtaposes acts of conversion with atrocities against the Pueblo people (Supplemental Figure 3).

In addition to religious iconography, in the Franciscan missions of the seventeenth century, Catholic dogma was orally transmitted through various genres of Spanish religious folk literature spoken in Castilian dialect (Espinosa Reference Espinosa and Espinosa1985:17, 243). They included traditional religious Spanish ballads (Espinosa Reference Espinosa and Espinosa1985:90, 97), hymns, prayers, and other religious verses pertaining to Christ of the Passion, the “cult of the Divine Child” (Espinosa Reference Espinosa and Espinosa1985:112), the Holy Family (Espinosa Reference Espinosa and Espinosa1985:114–116), and the Immaculate Conception of the BVM (Espinosa Reference Espinosa and Espinosa1985:118–119). During the Inquisition in sixteenth-century Old Spain, the Immaculate Conception—the then disputed belief that Mary was conceived without original sin—became accepted Catholic dogma and a central theme in Spanish folk literature.

War captains from all villages who resisted Otermin's reconquest of 1681 included indios ladinos—that is, Indigenous men educated in mission schools, some of whom even had Spanish half-brothers (Espinosa Reference Espinosa1942:135, footnote 72; Kessell Reference Kessell2008:97–98, 127). Among them were Alonso Catiti of Santo Domingo Pueblo, Francisco el Ollita of Cochiti (Keres), Francisco Tanjete of San Ildefonso Pueblo (Tewa), and others who learned to speak, read, and write Spanish as well as Spanish prayers, hymns, and religious stories (Espinosa Reference Espinosa1942:22; Kessell Reference Kessell2008:98–99; Preucel Reference Preucel2000; Preucel et al. Reference Preucel, Traxler, Wilcox and Schlanger2002:86–87). For Native children growing up in the 1630s, such as Esteban Clemente (Salinas and Tanos), Spanish folktales with a clear Catholic message would serve the purpose of indoctrinating them in Catholic dogma (Espinosa Reference Espinosa and Espinosa1985:23; Riley Reference Riley1999:156–157). I argue below that Turkey Girl tales represent a discursive nativistic response to these Spanish conversion efforts.

Mesa Top Villages, Revivalism, and Nativistic Resistance

To provide some historical context for Turkey Girl tales as a form of nativistic resistance, in this section I provide an overview of contemporaneous and complementary forms of northern Puebloan revivalism as a form of resistance to Spanish reconquest efforts between 1681 and 1694. Pueblo multiethnic groups (Keres, Tewa, Towa, northern Tiwa, Zuni) abandoned their pueblos along the Rio Grande (see Figure 2) and in many cases (re)occupied mesa-top ancestral sites in order to escape Spanish influence and revive ancestral traditions (Aguilar and Preucel Reference Aguilar, Preucel, Schmidt and Mrozowski2013, Reference Aguilar, Preucel, Duwe and Preucel2019; Preucel Reference Preucel2000; Preucel et al. Reference Preucel, Traxler, Wilcox and Schlanger2002:86–87). Turkey Girl tales recount how Corn Maiden and her turkeys escape up local canyons to the mountain sanctuaries.

According to Liebmann and colleagues (Reference Liebmann, Ferguson and Preucel2005:46), some Pueblo leaders used architecture and village locations in refugee communities to establish a revitalization movement. In the aftermath of the 1680 revolt, architectural form was used by new mesa-top villages to express “revivalist rhetoric” and by Pueblo leaders “to encode specific cosmological meanings and world views” (Preucel et al. Reference Preucel, Traxler, Wilcox and Schlanger2002:87). Using semiotic and space syntax analysis to study 10 Pueblo Revolt–era (1680–1696) mesa-top refuge villages, Liebmann and others (Reference Liebmann, Ferguson and Preucel2005) discovered significant differences in early (1680s) and later (1690s) villages with regard to the focus on multiethnic communal integration and adherence to a pro-revitalization ideology.

The earlier dual-plaza-oriented villages of Kotyiti (LA295; Keres co-resided with Tewa) and Boletsakwa (LA136; Jemez/Towa co-resided with Cochiti Keres) were architecturally more restrictive, suggesting centralized leadership. These earlier villages spatially controlled highly structured social interactions, such as the focus that Preucel describes as “a centrally located sipapu” (emergence place) and corner gateways marking the four directions, thereby architecturally encoding shared Keresan and Tewa cosmological views (Preucel et al. Reference Preucel, Traxler, Wilcox and Schlanger2002:87) that reflect a pro-revitalization ideology. The dual-plaza village of Kotyiti is of particular interest here due to the cosmological similarities in Keresan and Tewa Turkey Girl tales, discussed below. Liebmann and others (Reference Liebmann, Preucel, Aguilar, Douglass and Graves2017:146) argue that the presence of tuff-tempered Tewa wares found at Kotyiti suggests that Tewa migrants (potters) were allied and that they co-resided with Cochiti Keres at this dual-plaza village.

In contrast, the later, multiethnic villages of Astialakwa (Jemez/Towa), East Kotyiti (Keres and Tewa/Jemez?), and Dowa Yalanne (Zuni) had less centralized leadership and a dispersed layout that lent itself to informal interactions that aided communal integration (Liebmann et al. Reference Liebmann, Ferguson and Preucel2005:45), but without enacting a strong commitment to the earlier revitalization ideology. Notably, for this study, Dowa Yalanne reflected a mixture of high (unrestricted movement) and low (restricted movement) integration values similar to both Astialakwa's dispersed plan and Kotyiti's plaza-oriented plan (Liebmann et al. Reference Liebmann, Ferguson and Preucel2005:52–53). The social changes reflected in Pueblo Revolt–era refuge village architecture shaped and influenced village alliances that were, in turn, reflected in different degrees of commitment to revitalization ideology.

Appropriating and Repurposing Spanish Culture

Pueblo people also expressed resistance to Spanish culture through the appropriation and repurposing of Christian spaces and ecclesiastical objects. Jeanette Mobley-Tanaka (Reference Mobley-Tanaka and Preucel2002; also Gruner Reference Gruner2013:328; Liebmann Reference Liebmann and Preucel2002) has argued that even during times of apparent acquiescence to Catholic rule, Pueblo resistance was quietly carried out by the use of multireferential symbols, which mimicked Catholic tropes but carried hidden meanings. Examples include wearing crosses but interpreting them as representing dragonflies or using nonrepresentational abstract designs to hide images of turkey feet—perhaps alluding to Puebloan ideology of “movement” as survival. Similarly, noniconographic Catholic tropes explicitly expressed in Spanish religious literature (hymn, prayers) that conveyed Catholic authority were either mimicked, deliberately ignored, or destroyed—notably, Franciscan veneration of the BVM, Christ Child, and Holy Family (Espinosa Reference Espinosa and Espinosa1985:111–119).

Some scholars characterize the Pueblo rebellions as a nativistic rejection of foreign influence and a revitalization of precontact lifeways and traditional religion. Rather than the flat-out rejection of Spanish culture, Gruner (Reference Gruner2013:314) argues that the material evidence of Spanish influence found in refuge pueblos has clearly been repurposed by certain Pueblo people, such as the caching and appropriation of religious paraphernalia—for example, holy vestments, censers, and chalices (Gruner Reference Gruner2013:324). In one case, the Spanish-speaking indio ladino Juan was a baptized Native who joined the Pueblo Revolt and entered battle against the Spanish on horseback “wearing a red cloth stolen from the Galisteo mission in the style of a priest's sash” (Kessell Reference Kessell2008:120).

Liebmann (Reference Liebmann and Preucel2002:142) explains the appropriation of select Catholic religious paraphernalia as part of a deliberate strategy employed to (re)create traditional Pueblo identities. Moreover, Gruner views evidence that Pueblo Revolt–era leaders were appropriating and reusing Catholic ecclesiastical paraphernalia (e.g., vestments, censers, crosses, etc.) as evidence that these objects “were ritually neutralized” in the same way that the Spanish appropriated Indigenous sacred spaces, notably kivas (Gruner Reference Gruner2013:314). As an example, at Pecos, the Indigenous congregants razed their church and built a kiva with the brick rubble (Gruner Reference Gruner2013:318; also see Kessell Reference Kessell2008:125). Diego de Vargas noted similar practices during the Pueblo Revolt of 1696. At San Diego Pueblo, the floor of the abandoned church was littered with abandoned crucifixes that were covered with ashes and prayer feathers as a kind of purification rite (Espinosa Reference Espinosa and Hayes1998:252). Gruner posited that ritually purifying Catholic paraphernalia implies that the material and discursive relics of Christianity were believed to have real power, which must be “diffused before a new order could be reestablished” (Gruner Reference Gruner2013:31).

Although the Spanish viewed such repurposing as a form of blasphemy, Gruner points out that the incorporation of Spanish material culture into the revitalization movement was a well-established idiom of Indigenous resistance that predated the 1680 revolt, occurred in other Spanish colonial territories, and was practiced by leaders in the Pueblo Revolt revitalization movement (Gruner Reference Gruner2013:322).

Turkey Girl Tales: Idioms of Indigenous Resistance

In this section, I discuss Turkey Girl tales that reflected actual idioms of nativist resistance. I discovered that at least one Spanish religious folktale was deliberately appropriated and repurposed by Pueblo Revolt leaders as an expression of resistance to Spanish religious and cultural suppression. I focus on a Spanish Christianized folktale, “Estrella de Oro” (Gold Star), which originated in Castile, Old Spain, in the sixteenth century, before being transmitted to the missions in New Mexico with Franciscan friars (Espinosa Reference Espinosa and Espinosa1985:21–22) and remains popular to this day. My approach comports with Erina Gruner's definition of nativism as “the consolidation of indigenous identity achieved by appropriating and repurposing Spanish culture” (Gruner Reference Gruner2013:314). The tales that I collectively refer to in this article as Turkey Girl tales highlight, to varying degrees, the importance of Corn Maiden/Mother and her turkey charges in the ethnogenetic process of constructing a pan-Pueblo identity based on ancestral religious beliefs.

Folkloric Classification and Comparative Method

In this section, I discuss and apply the comparative method employed in folklore studies to argue that the Pueblo Turkey Girl tales represent an indigenous repurposing of a specific Spanish Christianized folktale, “Estrella de Oro” (Gold Star) #6 (Espinosa Reference Espinosa1937). This Spanish tale is classified in the Persecuted Heroine (Cinderella) tale type that diffused from the Near East to Spain between the thirteenth and sixteenth centuries. According to my analysis, it was appropriated and repurposed in several (n = 9) Northern Pueblo “Turkey Girl” variants.

Stith Thompson, an American folklorist, translated Swedish folklorist Antti Aarne's 1910 innovative motif-based classification system and enlarged it in scope. According to the Aarne-Thompson (AT) method of folkloric classification, the Persecuted Heroine (or Cinderella) folktale is classified as tale type 510A. Folkloric comparative analysis concluded that it originated in China (Waley Reference Waley1947) and spread to the Near East and to southern then northern Europe in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries (Dundes Reference Dundes1988:266; Mills Reference Mills and Dundes1982; see type B in Rooth Reference Rooth1951, Reference Rooth and Dundes1982). This is based on 12 shared narrative units or “motifs” involving a character, an event, or a theme (Aarne and Thompson Reference Aarne and Thompson1971; Thompson Reference Thompson1955–1958). Here, I replace the AT term “motif” with Lévi-Strauss's (Reference Lévi-Strauss1958) more-or-less synonymous term “mytheme” to reference generic units of narrative structure (Table 1).

Table 1. Mythemes of Southern Europe (Spain) Tales 510A + 480 (in bold).

Note: Number in parentheses reflects number of versions with this mytheme.

* Mytheme 6 in table type 510A is missing: midnight or sunset prohibition or promise.

The database of Spanish-Castilian-language Persecuted Heroine tales identified for this comparative analysis includes five tales dating to sixteenth-century peninsular Spain and eight tales traced to Spanish-speaking descendants of Spanish colonists living in northern New Mexico and southern Colorado in the early twentieth century. Based on their nearly identical mythemes, I infer that Spanish tales fitting the Persecuted Heroine tale type 510A diffused from peninsular (Old) Spain to the Rio Grande missions with Franciscan friars who enlisted them in the process of indoctrinating Native children into the Catholic faith (Espinosa Reference Espinosa and Espinosa1985:23).

The Old Spain group of tale type 510A includes “Estrella de Oro” (Gold Star; 5 and 6; Espinosa Reference Espinosa1937:10–11) and “Las Dos Marias” (Two Marias), “Puerquecilla” (Little Piglet; 111), and “Estrellita de Oro” (112; Espinosa Reference Espinosa1946).Footnote 1 The New Mexico and southern Colorado group includes tales in original Spanish or English translation: “La Oreja de Burro y la Cuerno Verde,” “Granito de Oro,” and “La Huérfana” (Lea Reference Lea1953); “Estrellita de Oro” (Hays-Gilpin Reference Hays-Gilpin and Crown2000); “Cinderella” (106), “The Golden Star” (107), and “The Jealous Stepsisters (108; Rael Reference Rael1957); and “Little Gold Star” (San Souci Reference San Souci2000).

Spanish Christianized Folktales Used for Conversion

In sixteenth-century Castilian Spain, variants of Persecuted Heroine tale type 510A incorporated a Christianized version of Near East Muslim subtale 480, “The Kind and Unkind Girls” (Mills Reference Mills and Dundes1982:180–192), in which the miracles of the BVM and her Test of Virtue figure centrally. I analyzed five peninsular (Old) Spanish tales classified as “Cinderella” tale type (510A and 480) and eight nearly identical tales from northern New Mexico and southern Colorado descendants of the Spanish colonizers told in the sixteenth-century Castilian dialect (Espinosa Reference Espinosa and Espinosa1985:17, 20). My comparative analysis revealed that all 13 tales shared 10–12 mythemes, of which 4–6 represent the Christianized message of the “The Kind and the Unkind Girls” tale (see Table 1). For example, in “Estrella de Oro” the heroine is asked to perform three acts of unkindness—such as “spank the [Christ] child,” “show disrespect to the old man” (Saint Joseph), and put dirt in the old man and child's food—but she does the opposite, showing kindness and compassion.

In other versions of the Spanish tale, she is asked to perform one or two acts of kindness, which she does obediently. In five tales, she is rewarded with a gold star on her forehead, recalling the Virgin Mary's crown of stars in the book of Revelation (12:1): “And a great portent appeared in heaven, a woman clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet and one her head a crown of twelve stars.” In contrast, her stepsister, who acts unkindly, is punished with a green horn on her forehead (envy) and/or a donkey tail (ignorance) on her chin. I maintain that “Estrella de Oro” was employed in the Franciscan missions' conversion of Native children as early as the 1630s. It is worth noting that San Miguel Chapel, a Spanish colonial mission church build in 1610 in Santa Fe, New Mexico, to this day houses a post–Pueblo Revolt statue of the Virgin Mary adorned with a crown of stars (Supplemental Figure 4).

Nativized “Turkey Girl” Tales

Like the Spanish folktale “Estrella de Oro,” the Indigenous Turkey Girl tales represent ethnolinguistically distinct variants (n = 9) of the Cinderella tale type 510A (all but one of which expunge 480). Although these Pueblo tales share at most nine out of 12 mythemes with the Spanish folktale, they represent thoroughly nativized variants of the tale. Several past studies confirm the presence of Spanish influence on Pueblo Indian folktales (Boas Reference Boas1922; Espinosa Reference Espinosa1937, Reference Espinosa and Espinosa1985:Appendix B, 240–250; Parsons Reference Parsons1918, Reference Parsons1939:1110–1012, Reference Parsons1994; Parsons and Boas Reference Parsons and Boas1920). Collected from diverse native informants in the early 1900s, these Pueblo tales are infused with ethnically distinct Indigenous characters, settings, and religious beliefs that are clearly associated with the Pueblo Revolt period revitalization movement. Aurelio Espinosa (Reference Espinosa and Espinosa1985:62–64) describes tales in this group as innovative variants of Spanish tales made by indigenous people who live “where Spanish culture hasn't taken deep root in spite of the widespread use of Spanish as the language of the community.”

The database of tales used here comes from Pueblo informants and ethnographers:

(1) Tewa: “The Turkey Girl” (Parsons Reference Parsons1994; Santa Clara), and “The Turkey Girl” (Valarde Reference Velarde1989; San Ildefonso)

(2) Keresan: “Turkey Mother” (Benedict Reference Benedict1931; Cochiti) and “Turkeys Befriend a Girl” (White Reference White1935; Santo Domingo)

(3) Zuni: “Turkey Herd” (Parsons Reference Parsons1918), “The Poor Turkey Girl” (Cushing Reference Cushing1901), “The Turkey Girl: A Cinderella Story” (Pollock Reference Pollock1996, based on Cushing Reference Cushing1901), and “The Good Child and the Bad” (Parsons and Boas Reference Parsons and Boas1920)

(4) Northern Tiwa: “A Little Cinderella” (De Huff Reference De Huff1922; Picuris)

I analyzed nine Turkey Girl tales to identify shared mythemes and their relationship to tale type 510A (and 480). Each tale was labeled with a letter related to its language group and a number for each tale in that group (see mythemes in Weiner Reference Weiner2018). They consist of two Tewa (T1 and T2), two Keresan (K1 and K2), four Zuni (Z1 to Z4), and one Tiwa (Ti1) tales. Of the 12 mythemes in the Spanish Cinderella tales, eight of the Turkey Girl tales contain an array of mythemes from 1 to 3 and 7 to 12. Tellingly, mythemes 4–6, the miracles of the Virgin Mary and her test of virtue, are omitted in all but one tale—a Spanish tale recounted by a Zuni consultant (Table 2).

Table 2. Turkey Girl Tale Mythemes Similar to Spanish “Persecuted Heroine” Tale Type.

Note: Number in parentheses reflects number of versions with this mytheme.

Eight of the nine Pueblo tales include the following nativized themes, all of which are parsed more fully into their ethnolinguistic variants in Supplemental Table 1. The heroine's name relates either to a kinship relationship to turkeys or corn; she is denied an invitation to a dance at an ancestral site; she is bathed in a river purification rite and transformed by the magical powers of her turkey charges into ceremonial attire; she is initially admired when arriving at the dance; she is subsequently accused of being a sorceress, and violence erupts against her or among her suitors; she breaks her promise to return to her turkeys by sunset; she hides from her attackers in a sacred lake, sipapu, cave, or shrine; abandoned, the turkeys flee into the mountains, or they flee with her to a “better place”; her turkeys escape captivity and fly in the four directions.

Because these are Indigenous tales, it is important to interpret them from an emic perspective provided by Native consultants and ethnographers as accurately as is possible for a nonnative reader (Boas Reference Boas1922; Cushing Reference Cushing1901; Parsons Reference Parsons1994; Parsons and Boas Reference Parsons and Boas1920; Velarde Reference Velarde1989; White Reference White1935). We can infer from the heroine's name—Turkey Girl or Turkey Mother—that she is the sole caregiver of domesticated turkeys who love her, whereas her human family (biological or foster parents) does not feed or care for her (T1, T2, K2, Z1). In other tales, her name suggests her role as the turkeys’ primary food provider—Corn Maiden or Mother: “full-kernel girl” (k'oke-anyo), or “sister of Yellow and Blue Corn Girls” (Z2, Z4, T1, Ti1). This is consistent with what we know historically about the relationship between Ancestral Puebloan women and their turkey charges, who depend on maize cultigen for food. So strong is the bond that both Pueblo people and turkeys in the tales refer to corn as “Mother” (Ford Reference Ford, Johannesson and Hastorf1994; Parsons Reference Parsons1939:39, 72–73, 124–125); for Keres at Cochiti, Corn Mother is “Uretsete” (Patterson-Rudolph Reference Patterson-Rudolph1997:8). In some of these tales, the heroine refers to her turkeys in kinship terms: “all her children”(T1), “elder and younger sisters” (Z1), and “tall brothers” (Ti1), recalling turkey imprinting on human caregivers mentioned earlier.

An orphan or foster child, the heroine is excluded from attending a ceremonial dance or festival at an ancestral site near her village—for example, Pe'sehre near Pecos (T1), Puye near Santa Clara Pueblo (T2), Yopatra Kadowima near Cochiti (K1), Ma'tsakä east of Zuni (Z2), and Hawikuh near Zuni for “dance of the Sacred Bird” (Z4). Some villages, such as Keresan Santo Domingo (Kewa) or Tompiro Pecos, were occupied and exploited as Franciscan missions. The practice of conducting masked dances, banned during the Kachina Wars of 1660s and again in 1675, at remote ancestral villages recalls how certain groups sought to escape the control of the civil and religious authorities by fleeing to ancestral mesa-top refuges.

In preparation for the dance, the turkeys administer the heroine's bath of purification in the river (T2; Parsons Reference Parsons1939:453–457) and then transform her with the flap of their wings (T1, Z1) or the stroke of a stick (T2, K1)—that is, a magic wand—into a beautiful Pueblo maiden properly prepared for a dance ceremony. Her short, lice-infested hair becomes shiny and long (K1, T2, Z4; Parsons Reference Parsons1939:454–455), and her dirty clothes become pristine ceremonial attire: black or white Hopi manta or blanket (Hopi being a major source of white cotton cloth; K1, T1), moccasins, and coral (T2) or turquoise jewelry (Z4, K1, T1). Several Turkey Girl tales reflect turkey husbandry practices reported by the Spanish in the 1600s (T1, T2, K1, Z2, Z4); that is, that turkeys enjoyed free-ranging during the day and were probably herded using a stick into a pen or corral (Z4) to be fed maize and kept safe from predators at night.

At the dance, the heroine is initially admired by all the young men, but soon conflict ensues when she forgets her promise to her turkeys to return by sunset (K1, T2, Z1, Z4) due to “excess of enjoyment” (Z2), when her mother believes her transformation was due to the heroine being “a black hearted witch” (K1, T2), or when she is scolded by her sisters for coming to the dance and flees (T1). In one case, she is pursued by a hostile crowd of men into the mountains, where an enormous turkey wing hides and protects her (T2). The social tension and threats of violence recall actual intratribal conflict between Pueblo factions in the 1670s and 1680s involving those who aligned with the Spanish and those who organized the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 (Espinosa Reference Espinosa1942; Liebmann et al. Reference Liebmann, Preucel, Aguilar, Douglass and Graves2017).

Corn Maiden's broken promise to return to her turkey “family” by sunset, perhaps feeding time when they are herded into pens (Z4), may reference the breakdown of the long-standing relationship and “love” (Z1) between domesticated turkeys and Pueblo women caregivers due to the unsustainable demands of the Spanish tribute on maize or following the drought and famine of the 1660s. Due to the adverse impact of maize tribute and drought, turkey flocks were apparently decimated along with ritually important feather prayer sticks and turkey-feather robes/shrouds. Later in the tales, turkeys—perhaps a metaphor for Pueblo people who fled to mesa-top villages—escaped their confinement by fleeing up the canyons to the mountain; for example, to Canon Mesa (Shoya-k'wikwi), to “top of hill” near Kyakima (Z1), to Canon of the Cottonwoods behind Thunder Mountain (Z2), or to “Turkey Track Mountain” (T2). The lived experience of flight to ancestral sites on mesa tops confirms the Puebloan belief that “life is movement” for Pueblo people (Duwe and Cruz Reference Duwe, Cruz, Duwe and Preucel2019:115; Naranjo Reference Naranjo, Varien and Potter2008).

In some of the tales, the heroine finds her turkeys, and together they escape into the place of emergence: the sipapu, where “there are a girl's footprints and turkey tracks to this day” (K1), into a “cave of shrines, into a better land” (T2), “into a hole to live happily with good spirits” (Ti1), or to a new home at Jemez” (perhaps Old Cochiti; K2). In one Tewa tale, she escapes into the lake of emergence, but without her turkeys (T1). In a Zuni version, she fails to find her turkeys, she goes home and cooks for her sisters, and her turkeys fly off alone to “a high rock” (Z1). In three versions of the tale, her turkeys fly off in the four directions without her, perhaps returning to the wild (Z1, T1, Ti1).

Importantly, eight out of the nine Turkey Girl tales collected are traced to Pueblo groups that joined the revolt. For that reason, I believe they were an integral part of resistance and revitalization necessary for pan-Pueblo ethnogenesis. Tales that offer a more optimistic view of restoring the bond between Pueblo people (turkeys) and Corn Maiden recount how they escape together perhaps to initiate future re-emergence and revitalization (K1, K2, T2). Others are less optimistic regarding revitalization in the future (Z1, Z2, Z4, T1, Ti1).

Conclusion

Before the arrival of the Spanish, turkey husbandry flourished first in the northern San Juan (500 BC–AD 1150) and subsequently in southern San Juan and Rio Grande Valley (AD 900–1680) areas. During the Early Agricultural period in the northern San Juan area, turkeys and their ritually important feathers came to be associated with a rainmaking ideology and symbolic complex that may have diffused north to the northern San Juan area with southern Uto-Aztecan-speaking maize farmers from the Tucson farming communities. Before spreading north with maize agriculture, this ideology had roots in a Mesoamerican rainmaking ideology associated with the deity Tlaloc and kachina, or rain beings. The archaeological records of sites in the Central Mesa Verde area (AD 600–1200) and Chacoan central and peripheral sites (AD 800–1150) suggest that turkeys remained a symbolically and ritually significant bird, perhaps as much as imported macaws or parrots.

For about a millennium, Ancestral Puebloan women (Corn Maidens/Mothers) across different ethnic groups experienced a close human-turkey relationship, characterized as a long-lasting social bond, which was probably a result—as least in part—of turkey imprinting on their human caregivers. Women tended their domesticated and wild turkeys; fed them a predominantly maize diet when possible; and harvested their feathers for prayer sticks, ceremonial costumes, and masks. Most turkey-feather blankets, woven on a loom frame using down twined on yucca cordage, have been recovered from burial contexts across the northern and southern San Juan and Rio Grande Valley regions. They were probably gifted to infants at birth, were valued for warmth throughout a lifetime, and served as a burial shroud in death.

The ritual/symbolic importance of turkeys for Ancestral Puebloans spanning over a millennium before the arrival of the Spanish is supported by multiple lines of evidence. Material evidence—such as turkey ritualized interments, feather prayer sticks and blankets/shrouds, and turkey images on small, ceremonial bowls, kiva walls, and rock art—suggests that Southwest regional turkey-centered rainmaking rituals and ideology predated and perhaps contributed to the fourteenth-century kachina religion. All of these socially and ritually important Indigenous traditions tied to turkey husbandry were adversely impacted by the Spanish maize and textile tribute (encomienda) systems and demands on native labor (repartimiento) of the mid-1600s, effectively ending Native turkey husbandry at Rio Grande Valley pueblos.

Despite this assault on Native culture, kachina ceremonialism continued clandestinely, forcing Pueblo people to reuse feathered prayer sticks and masks and, by the early 1700s, to replace turkey-feather burial wrappings with woolen blankets. In response, multiethnic Pueblo people (Keresan, Tewa, Zuni, Towa, and others) sought refuge and the revitalization of their ancestral traditions at post–Pueblo Revolt period mesa-top or remote villages. Around this time, Native people would appropriate and repurpose elements of Spanish culture and ecclesiastical materials as part of a pan-Pueblo resistance and revitalization movement.

A previously overlooked expression of resistance to Spanish culture, Turkey Girl tales collected by ethnographers in the early 1900s from Keresan, Tewa, Towa, northern Tiwa, and Zuni informants reflect the appropriation and repurposing of one or more Spanish religious folktales employed in seventeenth-century Franciscan conversion of Native children. I attribute the authorship of these tales to diverse Pueblo Revolt–era war captains who, as children, learned to read and write Spanish in Franciscan mission schools as early as the 1630s. Collectively, these tales reflect a spirit of pan-Pueblo ethnogenesis and resistance to Franciscan conversion efforts along with varying degrees of commitment to revitalization ideology.

Acknowledgments

During the past year of restricted access to collections due to COVID-19, I am indebted to the following museum curators and archivists for their time and assistance: Bridgette Ambler and Tracy Murphy, BLM Canyons of the Ancients Museum; Julia Clifton, Museum of Indian Arts and Culture; Tara Travis and Samuel Denman, Mesa Verde National Monument Research Center; James Krakker, National Museum of Natural History; Alessandro Pezzati, University of Pennsylvania Archaeology and Anthropology Museum; and Kari Schleher, Maxwell Museum of Anthropology. I also thank Laurie Webster, who shared her knowledge of turkey-feather blankets; and Matt Liebmann, who provided helpful feedback on Rio Grande Pueblo archaeology. Finally, I am indebted to the anonymous reviewers for their painstaking feedback, which undoubtedly improved the article.

Data Availability Statement

The turkey-feather blankets from Mesa Verde are stored at the University of Pennsylvania Museum (Philadelphia). Those previously stored at the Colorado Historical Society (Denver) have been repatriated (NAGPRA 25 U.S.C 3003). Those from Pueblo Bonito (Chaco Canyon) are stored at the American Museum of Natural History (New York) and at Aztec Ruins Museum (Farmington, New Mexico; [online archive tDAR]). The ceramics with turkey designs are stored at Canyons of the Ancients Museum (Cortez, Colorado); Chapin Archaeological Museum, Mesa Verde National Monument (Colorado); and the Indian Museum of Arts and Culture, Anthropology Lab (Santa Fe, New Mexico). Electronic databases listing all known turkey-feather artifacts, turkey-design ceramics, and mythemes of the Turkey Girl tales are in the possession of the author, available to qualified researchers on case-by-case basis.

Supplemental Material

For supplemental material accompanying this article, visit https://doi.org/10.1017/aaq.2021.111.

Supplemental Figure 1. Bandelier (or Biscuit B) Black-on-white bowl fragment, Pueblo del Encierro/LA70, Sandoval County, New Mexico. Catalog #55392/11. Collections of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Albuquerque District, at the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture/Laboratory of Anthropology.

Supplemental Figure 2. Pindi Black-on-white bowl fragment, Pindi Pueblo/LA1, Santa Fe County, New Mexico. Catalog #53403/11. Collections of the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture/Laboratory of Anthropology, Museum of New Mexico.

Supplemental Figure 3. Painting, artist unknown. Nuestra Señora de la Macana (Our Lady of the War Club), depicting statue of the Virgin Mary with the Pueblo Revolt behind her. Statue was brought to New Mexico by Juan de Oñate in 1598, known then as Our Lady of the Toledo [Spain] Sacristy. History Collections of the New Mexico Museum, Santa Fe, 2012.32.1.

Supplemental Figure 4. Painted wooden or terracotta statue of the Virgin Mary with crown of stars and Christ Child (undated, probably 1800s). San Miguel Chapel, Santa Fe, New Mexico.