Poor diet is a risk factor for increased prevalence of chronic disease( Reference Ezzati and Riboli 1 – Reference Pomerleau, Lock and McKee 4 ). Prevention of chronic disease should start early in life( Reference D'Souza and King 5 – 8 ). Low income and socio-economic deprivation have been associated with poorer dietary intakes( Reference Craig, McNeill and Macdiarmid 9 – Reference Pilgrim, Barker and Jackson 12 ) and therefore with increased risk for chronic disease( Reference Hamer and Mishra 13 ). Those living in deprivation are more likely to lack nutritional knowledge and cooking skills( Reference Siu, Giskes and Turrell 14 ). The lack of home-cooking skills reduces the likelihood of cooking and consuming freshly cooked meals( Reference Larson, Perry and Story 15 ), resulting in a low fruit and vegetable intake( Reference Crawford, Ball and Mishra 16 ). Additionally, poor cooking skills have been reported to be a strong predictor of ready-meal consumption( Reference van der Horst, Brunner and Siegrist 17 ) which can contribute to higher total energy, fat, salt and sugar intakes( Reference Anderson, Wrieden and Tasker 18 , 19 ). In recent years, purchases of ready meals have increased considerably in the UK( Reference Buckley, Cowan and McCarthy 20 ) due to their convenience and relative cheapness( Reference Mahon, Cowan and McCarthy 21 ) while home-cooking skills are declining( Reference Caraher, Dixon and Lang 22 ).

The Scottish Government has recognised the importance of improving diet and has produced several policy documents highlighting the need to promote health and nutrition interventions aiming to improve diet and reduce health inequalities( 23 , 24 ). The Scottish Government has stated that those on ‘a low income in particular require more support, education and skills development to allow people to break through barriers of food affordability and availability, and lack of food skills’( 23 ). Actions to break barriers should incorporate ‘practical and achievable steps supplemented by the promotion of healthy food choices and meal preparation to help the public take steps in moving towards a healthier diet’( 23 ). The relevance of health promotion during early years has also been recognised in government policies( 25 , 26 ). Thus increased food skills have been recently highlighted as a short-term outcome in the Maternal and Infant Nutrition Framework: ‘more parents and carers have the confidence and skills to implement good feeding and eating patterns’ which in turn will help to achieve national outcomes that allow a ‘best start in life’ and ‘longer and healthier lives’( 27 ). Cooking skills programmes (with healthy eating messages at their core) are a popular community nutrition intervention( 28 ) in line with the current policies( 23 , 29 ). However, studies formally addressing evaluation of their effectiveness are scarce( Reference Rees, Hinds and Dickson 30 ). Wrieden et al. reported results from an evaluation of a cooking skills intervention in which forty-one participants attending a 7-week cooking skills course significantly increased their self-reported fruit consumption from baseline to post intervention and reported a significant increase in confidence when following a recipe from baseline (67 %) to 6 months after the intervention (90 %)( Reference Wrieden, Anderson and Longbottom 31 ). A study conducted in the USA suggested that home meal preparation was related to improvements in diet/meeting dietary guidelines in young adults( Reference Larson, Perry and Story 15 ). Consistent results were also found in the formative evaluation of the ‘Cooking with a Chef Program’ which was conducted following a 5-week programme targeting low-income families in South Carolina, USA( Reference Condranksy 32 ). However, there are insufficient evaluations considering the long-term impact of these programmes. As evaluation of public health interventions is essential to determine programme effectiveness, accountability and adequacy including longer-term outcomes, the aim of the present study was to evaluate the impact of a cooking skills intervention on self-reported confidence about cooking skills and food consumption patterns by measuring at baseline, post intervention and 1 year after delivery.

Methods

Study design

This was a single group pre-test/post-test repeated measures design( Reference Wludyka 33 ).

Ethics

The first phase (baseline and post intervention) of the study was assessed by the Research and Development Manager of NHS Ayrshire and Arran board and was considered as a service evaluation. For the 1-year follow-up phase, ethical approval was granted by the University of Glasgow Medical Faculty Ethics Committee.

Programme background

Cooking skills programmes delivered by National Health Service (NHS) community food workers in NHS Ayrshire and Arran over the past 11 years have sought to raise awareness of the importance of healthy eating and to build up confidence and skills in cooking through practical, participatory sessions in an informal atmosphere. Initial programmes originally targeted one local authority area as a high proportion of the population in this area lies within the 15 % most deprived in Scotland( 34 ). However, Scottish Government funds to improve Maternal and Infant Nutrition allowed funding for work among the group known as ‘early years’ (comprising parents of nursery age children) across the whole of the NHS board area covering North, South and East Ayrshire Local Authorities.

Recruitment and delivery of cooking skills programme

Early Years Managers from each local authority identified target nurseries based on vulnerability of children and families. While areas of high deprivation – based on the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD) – were not always specifically targeted, postcodes of participants showed that this was usually the case. Participants, mainly parents or key carers, were recruited through informal ‘meet and greet’ sessions held by community food workers at target nurseries. Community food workers attended the nurseries at dropping off and picking up times and spoke with parents including offering activities around food to increase engagement. Activities included games or tasting food such as pancakes or smoothies, which allowed conversations around food to develop and an invitation to cooking skills sessions to be offered where appropriate.

The programme consisted of weekly practical sessions lasting for 2 h with duration of 4 to 8 weeks. The aims of the cooking programme were to:

-

1. increase awareness of the importance of food to good health;

-

2. extend skills in shopping, cooking and budgeting and thereby improve eating behaviour; and

-

3. increase confidence and self-esteem by developing new skills and working with a wide range of foods.

The number of weeks (4–8 weeks) the programme ran was mainly dependent on the participants’ wishes and availability and on the facilities available in the different venues to comply with health and safety requirements; this was identified following risk assessments. Groups consisted of a maximum of eight participants to allow for interactive participatory group work, for everyone to prepare and cook their own dishes, and to comply with health and safety requirements. The course content started in week one with a group activity introducing and discussing the Eatwell plate through a game with replica foods and examples of food products. Subsequent session content varied depending on the specific needs, wishes and skills of the participants. However, the format of each session included participants each preparing and cooking one or more dishes to take home, a related nutrition game or activity on nutritional messages or information provided or on shopping skills particularly label reading, and discussion of relevant supporting resources. An example session is minestrone soup with garlic bread, with a discussion on stocks and understanding salt content on labels, types of bread and spreading fats, and also including taste, nutrition and cost comparisons with bought soup (processed, ready-made). As a key part of the programme participants were provided with Munch Crunch 2( 35 ), a recipe book of cheap, easy and healthy recipes developed by the community food workers over previous years to develop skills and confidence to cook at home. All food for all participants was provided each week, as was some basic equipment for participants to take and use at home.

Evaluation methodology

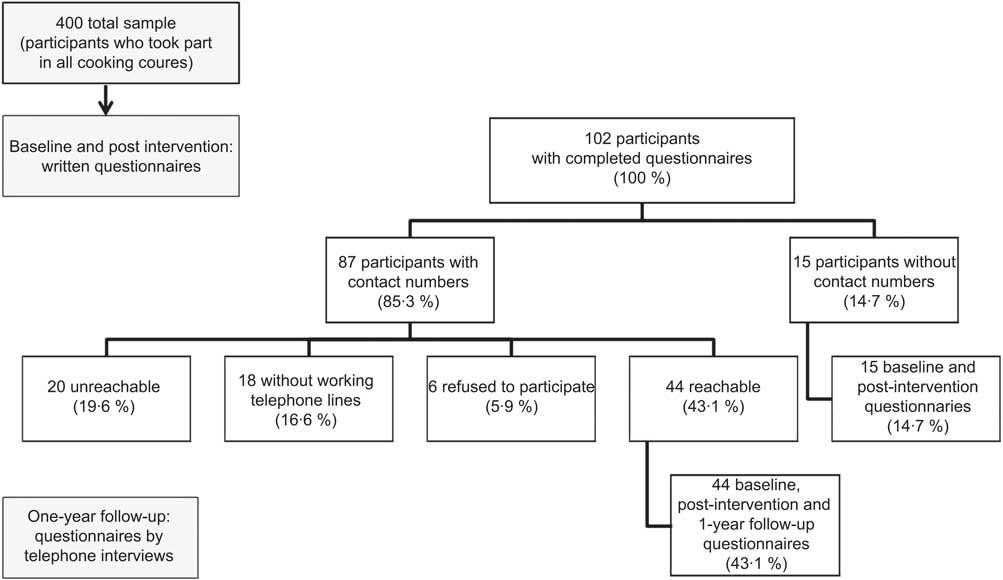

With the support of an NHS evaluation officer, pre-intervention questionnaires (baseline) and post-intervention questionnaires (final session) were given to all parents attending programmes from September 2010 to January 2011. All questionnaires were self-completed by participants. Pre-intervention questionnaires were completed at the beginning of the programme (week 1) and post-intervention questionnaires were completed always on the final session (week 4–8) independent of the programme duration. Both questionnaires took 5 to 10 min to complete. Participants who did not attend final sessions were contacted by telephone to ensure questionnaire completion; this could be done over the telephone or by post. Programme participation and questionnaire completion rates are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 Programme participation and questionnaire completion rates

For the 1-year longitudinal follow-up evaluation, participants who had taken part in a cooking programme over the September 2010–January 2011 period and had also completed both (pre- and post-intervention) questionnaires were contacted one year after participation by telephone to ask if they wished to take part in the 1-year follow-up evaluation. At the start of the telephone conversation, participants were given information about the 1-year follow-up study and were asked if they wished to participate. Participants who provided informed oral consent were asked to complete the 1-year follow-up questionnaire over the telephone. The researcher read the questions and all information was recorded. The telephone interview lasted no longer than 10 min. After collection, all data were kept confidential.

Evaluation questionnaires

Baseline (pre-intervention) evaluation was conducted using an early and shortened version of a validated questionnaire( Reference Barton, Wrieden and Anderson 36 ). The decision to use a shortened version of the questionnaire was based on previous experience of cooking programmes. The participants in these groups were often vulnerable parents with relatively low literacy levels. The questionnaire comprised closed questions on a Likert-style scale. Six items from the validated questionnaire were used as core questions in the baseline questionnaire: (i) ‘How confident do you feel about being able to cook from basic ingredients?’; (ii) ‘How confident do you feel about following a simple recipe?’; (iii) ‘How confident do you feel about tasting food that you have not eaten before?’; (iv) ‘How confident do you feel about preparing and cooking new foods?; (v) ‘How often do you eat fruit?’; and (vi) ‘How often do you eat vegetables or salad (not including potatoes)?’. In addition, a question on ready meals was added: ‘How often do you eat ready meals?’. Confidence was rated on a scale from 1 to 7 (‘not at all confident’ to ‘very confident’). To determine food consumption patterns, participants were asked to indicate how often they consumed ready meals, vegetables and fruit using the following scales: from 1 = ‘never’ to 7 = ‘more than once a day’ for ready meals; from 1 = ‘less than once a week’ to 7 = ‘more than twice a day’ for vegetables and salads; and from 1 = ‘less than once a week’ to 6 = ‘2 or more times a day’ for fruit. To aid accurate completion of the fruit and vegetable questions, participants were given information on fruit and vegetable portion sizes prior to questionnaire completion. At the end of the programme (post intervention) participants were asked to answer the same core questions used in the baseline questionnaire plus additional ones to evaluate the programme's effectiveness: on programme enjoyment, self-perception of dietary changes and whether their food knowledge had increased.

The 1-year follow-up questionnaire included the same questions used at baseline and post intervention. Participants were additionally asked if the programme had impacted on family eating habits (closed question, yes/no) and if what they learnt had benefited their family, improved their overall confidence, boosted their confidence to learn other skills and influenced their employability (all presented as Likert-style scales, from 1 = ‘not at all’ to 7 = ‘very much so’).

Statistical analysis

All data were analysed using the SPSS statistical software package version 17·0. The consistencies of the three questionnaires were tested using Cronbach's α in the same population. The average Cronbach's α values for baseline, post-intervention and 1-year follow-up questionnaires were 0·822, 0·708 and 0·713, respectively. The reliability scales were tested in four items for confidence questions at baseline (n 102; range 0·720–0·846), four items for confidence questions at post intervention (n 102; range 0·513–0·777) and eight items for confidence at 1-year follow-up (n 44; range 0·643–0729). The four items in baseline and post-intervention questionnaires were chosen because they assessed constructs for confidence in the same way as the original survey( Reference Barton, Wrieden and Anderson 36 ). The eight items assessed in the 1-year follow-up questionnaire included the same four items for confidence assessed at baseline and post intervention and four more items (benefits for family, overall confidence, confidence to learn other skills and influenced employability). The other items of the questionnaire were not included in the reliability analysis because they were assessing different constructs (food patterns). Our scores were slightly lower than the ones for confidence (0·86) reported by Barton et al.( Reference Barton, Wrieden and Anderson 36 ) but showed good internal consistency.

Data from the questionnaires were analysed to evaluate changes between baseline, post intervention and 1-year follow-up. Data were analysed for all participants who completed all three questionnaires (completers). Data were not normally distributed; therefore non-parametric tests were used. Questions related to confidence to cook from basic ingredients, follow a simple recipe, new foods and preparing and cooking new foods between stages (baseline, post intervention and 1-year follow-up) were analysed using Friedman's two-way ANOVA by ranks followed by the post hoc Wilcoxon signed rank test. Differences in food consumption patterns were tested using Wilcoxon's test. Comparisons between participant characteristics were analysed using the χ 2 test. Significance was accepted at P < 0·05.

Results

A total of 400 participants took part in the cooking skills programme, of whom 102 completed and returned both the baseline and post-intervention questionnaires during the evaluation period. Eighty-seven of these participants had provided telephone contact numbers, while fifteen did not provide a telephone number. Of the eighty-seven participants, forty-four were accessible by telephone one year later and gave oral consent to complete the 1-year follow-up questionnaire (Fig. 1).

The majority of participants in the baseline and post-intervention study were female and under 45 years old. Most participants fell into SIMD quintiles 1 and 2 and attended at least four sessions. Characteristics in the 1-year follow-up group were similar to those of the total group (baseline and post intervention except for location, P = 0·004; Table 1). No differences in gender (96 % females), age (78 % under 45 years old) and SIMD quintiles (71 % living in quintiles 1 and 2) were observed between participants who were not accessible for follow-up (n 56) and those who completed follow-up questionnaires (n 44). However, participants who were not accessible for follow-up were different from the ones who were accessible in the number of sessions attended, with 40 % attending fewer than four sessions (P = 0·004).

Table 1 Characteristics of participants: parents of nursery age children from deprived communities in Ayrshire and Arran, Scotland, who attended a cooking skills intervention in September 2010–January 2011

SIMD, Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation.

*For comparisons between baseline/post intervention and follow-up. Statistical significance at P ≤ 0·05 using the Wilcoxon signed ranked test.

Confidence

For participants who completed both baseline and post-intervention questionnaires (n 102), median values (25th, 75th percentiles) at baseline v. post intervention for self-reported confidence in cooking using basic ingredients were 5 (3, 6) v. 7 (6, 7); in following a simple recipe were 5 (4, 6) v. 7 (6, 7); in tasting new foods were 5 (3, 6) v. 6·5 (6, 7); and in preparing and cooking new foods were 5 (3, 6) v. 6 (6, 7).

The change in median confidence ratings between baseline, post intervention and 1-year follow-up for completers (n 44) is shown in Table 2. All median confidence aspects of cooking were statistically significant between the three time points: cooking using basic ingredients (P < 0·001), cooking following a simple recipe (P < 0·001), tasting new foods (P < 0·001) and preparing and cooking new foods (P < 0·0015).

Table 2 Median values for confidence ratings and patterns of ready-meal, vegetable and fruit consumption at baseline, post intervention and 1-year follow-up in completers (n 44): parents of nursery age children from deprived communities in Ayrshire and Arran, Scotland, who attended a cooking skills intervention in September 2010–January 2011

Δ, change; P25, 25th percentile; P75, 75th percentile.

*Scale values are from 1 to 7 (from ‘not at all confident’ to ‘very confident’).

†Scale values are from 1 to 7: 1 = ‘never’; 2 = ‘1–3 times a month’; 3 = ‘once a week’; 4 = ‘2–4 times a week’; 5 = ‘5–6 times a week’; 6 = ‘once a day’; 7 = ‘more than once a day’.

‡Scale values are from 1 to 7: 1 = ‘less than once a week’; 2 = ‘once a week’; 3 = ‘2–4 times a week’; 4 = ‘5–6 times a week’; 5 = ‘once a day’; 6 = ‘twice a day’; 7 = ‘more than twice a day’.

§Scale values are from 1 to 6: 1 = ‘less than once a week’; 2 = ‘once a week’; 3 = ‘2–4 times a week’; 4 = ‘5–6 times a week’; 5 = ‘once a day’; 6 = ‘2 or more times a day’.

Post hoc analysis showed that median confidence in cooking using basic ingredients increased significantly from 5 at baseline to 7 at post intervention (P < 0·05) but was not maintained, as it decreased slightly but significantly to 6 at 1-year follow-up (P = 0·033). Median confidence in following a simple recipe increased significantly (P < 0·05) from 5 at baseline to 7 at post intervention. Confidence was maintained from post intervention to 1-year follow-up (median 7, P = 0·067). Confidence in tasting new foods increased significantly (P < 0·05) from baseline (median = 5) to post intervention (median = 6); however, at 1-year follow-up, median confidence level decreased significantly (P = 0·002) again to the baseline value. At baseline, median confidence in preparing and cooking new foods was rated 5 and this rating increased significantly to 6 at post intervention (P < 0·001). From post intervention to 1-year follow-up, no change in ranking for confidence in preparing new foods was reported with a median of 6 (P = 0·083).

Participants’ confidence increased from baseline to post intervention for all evaluated aspects of cooking. These changes in confidence were retained at 1-year follow-up only for following a simple recipe and preparing and cooking new foods. In the case of cooking using basic ingredients and tasting new foods, the confidence level decreased significantly (P < 0·05) from post intervention to 1-year follow-up; however, these decreases did not drop to baseline levels.

Food consumption patterns

Median (25th, 75th percentiles) patterns of food consumption at baseline v. post intervention for participants who completed both baseline and post-intervention questionnaires (n 102) were as follows: 4 (2, 6) v. 3 (2, 6) for ready meals; 4 (3, 6) v. 5 (4, 6) for vegetables; and 4 (3, 5) v. 5 (3·2, 6) for fruit. Median values for patterns of food consumption for completers (n 44) and changes are shown in Table 2. For completers, median baseline consumption of ready meals was 2–4 times/week while a reduction to 1 time/week was reported post intervention; at 1-year follow-up, the self-reported consumption of ready meals remained at 1 time/week. There was a significant difference (P < 0·001) between the consumption of ready meals from baseline to post intervention which was kept also at 1-year follow-up (P = 0·545). Median vegetable consumption at baseline was 2–4 times/week and increased significantly (P = 0·028) to 1 time/d post intervention. This increased frequency of vegetable consumption was still reported at 1-year follow-up (P = 0·177). Median fruit consumption at baseline was 5–6 times/week and increased significantly to 1 time/d post intervention (P < 0·001); this increase remained at 1-year follow-up (P = 0·170).

Knowledge, diet improvement, further benefits

All participants (100 %) agreed that they had more knowledge of food after taking part in the programme (both at post intervention and 1-year follow-up). Specific comments about knowledge given at follow-up mostly concerned an increased awareness of the nutritional content of food (40·9 %), cooking from raw ingredients being healthier than ready meals (36·4 %), meal planning (food preparation within budget; 6·8 %), awareness of the proportions of different food groups needed in the diet (6·8 %) and increased awareness of the importance of consumption of fruit and vegetables in the diet (4·5 %). When participants were asked if they considered themselves to have a more balanced diet, 97·1 % and 84·1 % reported that they thought they did have a more balanced diet because of the cooking programme at post intervention and 1-year follow-up, respectively.

At post intervention, when asked if they enjoyed participating in the cooking programme, all but one of the participants answered yes to this question (no further comments were expressed for this response). When asked what they had enjoyed about the cooking programme, participants gave a range of comments including ‘cooking and trying new and/or healthier foods’, ‘it being enjoyable’, ‘a helpful demonstrator’, ‘learning new skills’ and ‘gaining confidence and knowledge on nutrition/healthy eating and free of cost’. All participants reported that they would recommend the cooking programme to others.

At 1-year follow-up participants were also asked about their perception of benefits on family members in terms of nutrition/healthy eating after taking part in the programme. Fifty per cent of participants ‘strongly agreed’ and the remaining either ‘slightly agreed’ or ‘agreed’ (47·7 %) that the programme provided benefits for their families. The majority of the participants also agreed that the cooking programme had improved their overall confidence, with 50·0 % strongly agreeing and 36·4 % agreeing or slightly agreeing. A similar response rate was recorded for the perceived confidence to learn other skills in which 43·2 % of participants strongly agreed and 40·9 % agreed or slightly agreed. On the perception of being more employable after the course, 70·4 % of participants had a level of agreement, 13·6 % felt neutral and 16·0 % disagreed. Thus, overall self-perception of benefits, confidence on gaining new skills and being more employable were positive with high levels of agreement.

Discussion

To our knowledge, the present study is the first UK-based one to report a longitudinal evaluation with 1-year follow-up interval of the effectiveness of a cooking skills programme. We obtained a moderate (43 %) response rate at 1-year follow-up which is similar to other evaluation studies using telephone-based interviews in low-income populations( Reference Chang, Brown and Nitzke 37 ). Our results showed that the cooking skills programme appeared to have a long-term positive effect on participants’ cooking confidence in using basic ingredients and following simple recipes. Further effectiveness of the programme was shown in participants’ reported improved healthful eating patterns (reduced consumption of ready meals and higher consumption of vegetables and fruits) from baseline to post intervention and maintenance of these patterns at 1-year follow-up.

Cooking skills programmes have previously been shown to improve participants’ confidence in certain aspects of cooking, e.g. following a simple recipe, and thus our observations are in line with other studies( Reference Wrieden, Anderson and Longbottom 31 , Reference Condranksy 32 ). Nevertheless, comparisons should be made with caution as our study lacked a control group whereas Wrieden et al.( Reference Wrieden, Anderson and Longbottom 31 ) used a controlled before and after design for their study. Even though our study did not have a control group, the participants acted as their own controls and changes across time are reported in the same participants, thus our results are robust. Furthermore, the use of a randomised controlled trial for the evaluation of this community-based intervention had ethical and practical implications, particularly when funding is short term; these limitations are also described by others( Reference Victora, Habicht and Bryce 38 ).

Improvements in healthy eating patterns such as fruit and vegetable consumption have also been reported in participants taking part in cooking skills programmes( Reference Condranksy 32 , Reference Brown and Hermann 39 ); although again direct comparisons with other studies are difficult since methodologies to assess dietary intake differ. To our knowledge, maintenance of self-reported eating patterns one year after a cooking skills programme has not been previously reported and thus our study provides new information on the potential longer-term impact of cooking skills programmes on families’ health.

Our results highlighted a significant decrease in the consumption of ready meals which could be partly attributable to the increased skills and confidence in cooking and preparing foods and the knowledge gained of the nutritional composition of convenience products. Indeed, Brunner et al. concluded that the more consolidated nutrition knowledge and the higher the cooking skills, the more reduced the consumption of convenience food( Reference Brunner, van der Horst and Siegrist 40 ).

Further benefits of the programme stressed the importance of enjoyment and social interaction which seems to help build confidence, capacity and form cohesive communities. Participants reported this as one of the most attractive features of the programme itself. Certainly, an exploratory trial to gather views of deliverers and community members involved in cookery programmes throughout Scotland emphasised an increase of participants’ social skills after completion of the programme( 28 ). Also, other evaluations of cooking skills programmes targeting youth and older people have revealed similar outcomes( Reference Brown and Hermann 39 , Reference Keller, Gibbs and Wong 41 , Reference Thomas and Irwin 42 ).

The present findings may imply the need for further contact or follow-up support with participants of cooking skills programmes as a way to support maintenance of changes since we showed that these changes appeared to diminish after the intervention took place, particularly in the case of confidence in cooking using basic ingredients and tasting new foods. This suggests that the cooking skills intervention has increased participants’ confidence in different aspects of cooking but the effects seem to be greater when they have just finished the intervention; therefore, additional interventions or support may be necessary in order for participants to maintain their confidence seen at post intervention. However, it is promising to see that the positive behaviour changes made did not diminish to baseline levels and therefore a refresher cooking skills programme after 6 months or a year may be a way of ensuring positive messages and actions are maintained. Community-based interventions aiming to improve diet-related outcomes are complex interventions that require the involvement of several stakeholders for sustainability, but long-term policy commitment (e.g. funding) is essential for sustainable outcomes( 43 ).

Despite its strength in being the first longitudinal study of its kind to include a long-term follow-up in the UK, there are a number of methodological limitations to consider. First, the use of a shortened version of a validated questionnaire as well as self-reported questionnaires on food consumption may have skewed the information as participants could have tried to impress the interviewers by under- or over-reporting their responses. Furthermore, social desirability or approval bias is higher in women( Reference Hebert, Ma and Clemow 44 ). Questions on frequency of fruit, vegetable and ready-meals consumption may not be reliable as portion sizes were not reported; instead participants reported only the frequency of eating these foods. However, there was a brief discussion on what constitutes a portion of fruit and vegetables prior to completion of baseline questionnaires to aid accuracy. A control group could have strengthened the findings reported here but it was not possible to include one as discussed above. Consequently, due to its longitudinal nature, the present study contributes important information to fill a gap in the literature in terms of long-term effects of cooking skills programmes. Nevertheless, the results should be interpreted with caution as just 10 % of the original participants in the programme completed all evaluation components. These programmes are commonly used as public health nutrition interventions to contribute to dietary improvement but they are not often evaluated in terms of their long-term impact. In many circumstances this is due to the nature of short-term funding for such interventions and programmes, but also as shown another contributing factor may be the low response from participants to participate in evaluation processes.

Conclusions

The effectiveness of the cooking skills programme was reflected in the positive results seen. Our results suggested that participants benefited from the intervention, whereby their overall confidence and eating habits improved and most changes were maintained one year after. Further qualitative comments were mostly positive and highlighted the importance of the social component of the course. This suggests that the intervention has benefited participants’ eating habits and health not only in the short term, but also in the long term.

Acknowledgements

Sources of funding: The cooking skills programme was funded by the Scottish Government (CEL36). Conflicts of interest: There are no competing interests. Authors’ contributions: A.L.G., study design, analysis, interpretation of results, writing and editing, supervision. E.V., telephone interviewing, analysis, interpretation of results, writing. P.S.L., telephone interviewing, analysis. F.S., supervision and delivery of community programme, study design, writing and editing. A.P., study design, writing and editing.