On 25 August 1918, one of colonial Singapore's most notorious murders occurred at the Globe Hotel on 326 North Bridge Road. That night, Sarah Liebmann, the proprietor of the public house, was bludgeoned with an iron bar and then strangled to death. Emil Landau, an elderly man who resided at the Globe, was also murdered by strangulation that night.Footnote 1 A few days later, Liang Ah Tee, a “bar boy” employed at the hotel, confessed to the murders. By the time the case went to trial, however, Liang was claiming innocence. He pleaded with the judge through a court interpreter, “I didn't kill these people […] the police forced me to make a confession”.Footnote 2 He was nonetheless convicted by a jury and sentenced to die by judicial hanging. The execution took place on the morning of 30 October, with Liang reportedly breaking down before “usual formalities” took place and “life was declared extinct”.Footnote 3 The case was remembered as one of “the most brutal crimes that have ever been committed in the Colony”.Footnote 4

This article analyses three cases of murder perpetrated by Chinese men who worked as domestic servants in Singapore between the 1910s and the 1930s. In addition to the Globe Hotel murders, I analyse the stabbing of Wong Chee by fellow servant Ee Ah Lak in 1925 and the killing of Teo Chye Neo by her young Hainanese servant, Yeo Tin Keng, in 1933. By analysing these crimes and the responses of the colonial state and the press to them, I aim to illuminate aspects of domestic servants’ lives that would otherwise remain unknown. Despite the fact that they predominated in domestic service until the 1930s, there has been little scholarly research on this group of workers. Male servants are inadequately researched in part because of the lack of government regulation to which they were subjected. The provisions of Master and Servant Law were inherited from Britain and could be drawn on in Singapore to deal with servant insolence, neglect of duty, and absence without leave.Footnote 5 However, recruitment of servants, the terms of employment, and wages were determined not by the government but by the Hainanese kongsi, a dialect-based community that represented the majority of Chinese male servants in Singapore.Footnote 6 The lack of official intervention has ensured that there are limited sources that leave us with an impression of servants’ lives. One of the few instances when Chinese male servants were subject to governmental control, and thus appear in the archives in great detail, was when they were charged and convicted of breaking the law.

My analysis of digitized English-language newspapers and Coroner's Court records uncovered seventeen alleged violent crimes committed by servants between 1910 and 1939, twelve of which led to conviction. They included three murders, four attempted murders, one attempted murder/suicide, and four convictions for causing bodily hurt or grievous bodily hurt. Eleven of the twelve violent crimes were perpetrated by Chinese male servants. In 1921, there were roughly 12,000 Chinese men working as servants in Singapore.Footnote 7 Considering this, eleven convictions for violent crimes is a surprisingly small figure. Convictions of employers for violent crimes against servants were also rare.Footnote 8

While Chinese men convicted of violent crimes may not have been representative in terms of the domestic servant workforce, these cases nonetheless tell us a great deal about this group of workers. The most detailed insights into Chinese men's lives in Singapore are provided by three cases of murder that took place a decade apart. In addition to the extremely comprehensive reports of the press, murder cases were also subject to Coroner's Court proceedings, resulting in a rich, if at times patchy, legal archive.Footnote 9 As journalists, lawyers, and judges sought to understand the nature of the crimes and those responsible for them, they recorded minute details of domestic servants’ lives. Singapore's residential and commercial enclaves were organized along lines of race and class.Footnote 10 Chinese male servants moved across these divisions as they worked in elite and middle-class households, laboured in high-end and low-class hotels, and socialized amongst the Chinese working classes. As police and prosecutors retraced the steps of the Chinese men involved in crimes of violence, they inadvertently provided glimpses into the social worlds of Singapore in the interwar years.

Also preserved within the records of murder cases are the statements and testimonies of servants as witnesses and perpetrators. The accounts of domestic workers were provided in Hainanese, Hokchia (Foochow/Fuzhou), or other Chinese languages that were then interpreted and recorded in English. While they were undoubtedly altered by the translation process and influenced by the intimidating environments of police stations and court rooms, these first-hand accounts are invaluable. They provide one of the few avenues through which we can access servants’ voices.Footnote 11

The use of Coroner's Court records to track the lives of working-class people in Singapore was an approach pioneered by James Francis Warren in his work on rickshaw pullers and prostitutes.Footnote 12 By focusing on domestic servants, this article takes Warren's work in a new direction. My methodology resembles that of Tim Meldrum, who analysed London Consistory Court records in order to illuminate the lives of servants. Meldrum drew on servants’ voices within the ecclesiastical court records as they gave testimony about the marital disputes of their employers.Footnote 13 The records used in this article are rather different insofar as they deal with crimes committed by servants. They provide opportunities for considering how servants fared in the criminal justice system – a key regulatory arm of the colonial state.

Scholars of domestic service have long contended that domestic life in the colonies was imbued with deep political significance. They have shown how mastery over “native” servants was viewed in colonial societies as a symbol and a practical expression of colonizer status.Footnote 14 Encounters between master and servant had the potential to reinforce or challenge colonial hierarchies.Footnote 15 The sometimes violent encounters between masters and servants in the confines of white colonial homes were a site of public commentary and governmental intervention.Footnote 16 The murder cases analysed in this article do not fit the usual definition of domestic service as involving a white employer and a native servant engaged in a private home. They took place not only in British homes, but in Chinese households as well as in commercial establishments. The men convicted of crimes were referred to as “servants” regardless of whether they laboured in private households, hotels, bars, or within company messes. The crimes involved violence towards employers as well as between servants. As they expose the diversity of situations in which men categorized “servants” were employed, these three cases challenge us to think about colonial domestic service in new ways.

In this article, I use the definition of domestic service as being “the work of an individual for another individual or family, in carrying out personal household tasks such as cleaning, cooking, childcare, and carework in general”. It is labour performed neither on the basis of “a social or kinship obligation, nor as a favour or kindness” but as “a definite ‘service’”.Footnote 17 Included within the definition of domestic service is care work performed in the context of commercial establishments. This reflects colonial conceptions of domestic service in Singapore. In defining the category of “personal service”, colonial statisticians, like the general public, did not differentiate between “domestic servants” engaged in private homes and those working in commercial establishments.Footnote 18

By analysing murders that occurred in homes as well as businesses, and by considering violence between servants as well as towards employers, this article takes up the call to consider domestic service beyond the domain of the household and builds on recent work that has examined domestic work in the more public realm of hotels and steamships.Footnote 19 This article also seeks to examine the lives of servants outside of their relationships with employers. The Sarah Leibmann (1918) and Teo Chye Neo (1933) murders illustrate that abuse and condescension on the part of employers were a catalyst for violence by some Chinese servants, whether they were employed in British or Chinese households. Yet, as the Wong Chee murder case (1925) demonstrates, acts of violence were also motivated by factors outside of the master-servant relationship. In this particular case, tensions between domestic workers arising from intimacy as well as financial stress culminated in a frenzied act of violence.

DOMESTIC SERVICE AND VIOLENT CRIME IN SINGAPORE

Colonial Singapore, like other port towns in Southeast Asia, was marked by its cultural, social, and religious heterogeneity. In 1921, the population of over 425,000 people included a very small number of “Europeans” (mostly of British origin), a slightly larger Eurasian community, and a sizeable Malay and Indian population. This cosmopolitan city was one governed and organized according to notions of “race” and divisions of class. Yet, as Lynn Hollen Lees has shown, it was also one in which the Asian middle classes mingled, forging cross-ethnic alliances and connections.Footnote 20 The Chinese community, which consisted of 74.5 per cent of the total population in 1921, was a diverse one.Footnote 21 It included Straits Chinese (Peranakan) people, who had been resident in Malaya for generations and who had married into local Malay communities, as well as a larger overseas-born Chinese (huaqiao) community.Footnote 22 In addition to divisions of citizenship, Singapore's Chinese community was divided along lines of dialect, clan, and class, which determined social status and occupation.Footnote 23 Of the major dialect groups, the Hokkiens were the most prominent, followed by the Teochews, the Cantonese, the Hakkas, and the Hainanese.Footnote 24

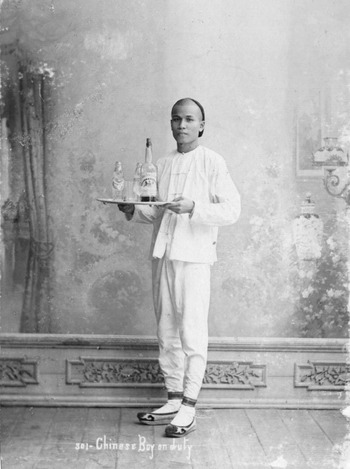

Domestic work in Singapore was organized around a hierarchy of race and gender. In 1921, there were 19,369 domestic servants employed in Singapore. Men made up sixty-four per cent of the servant population, with most drawn from the Chinese community and particularly from the Hainanese dialect group.Footnote 25 Hainanese men worked in the homes of wealthy British, Eurasian, Chinese, Indian, and Arab residents of Singapore where they were employed as cooks and houseboys, as depicted in Figure 1. In large households, Chinese men were employed alongside Indian and Malay men, and (in households with children) Chinese ayahs (nannies).Footnote 26 Within Chinese households, young bonded female servants, called mui tsai, were often also present.Footnote 27 As well as working in private homes, Chinese men, described variously as “servants”, “houseboys”, and “boys” (Figure 1), were employed in mess houses (share houses), commercial lodging-houses, and police and army barracks. They also provided personalized care in high-class hotels, such as the Hotel de l'Europe, Raffles, and the Adelphi, where each guest was allocated a “boy” to attend to their particular needs. In addition, they were engaged as general servants within clubs and public houses.Footnote 28

Figure 1. “301 – Chinese Boy on duty”, Lambert and Co, Singapore, c.1900.

University of Leiden, Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies, 50196.

While Hainanese men predominated in domestic work in Singapore, men from the Hokchia dialect group also worked as servants.Footnote 29 Hokchia domestic workers commanded lower wages than Hainanese men, receiving between $15 and $25 in wages a month in the mid-1920s, depending on their role.Footnote 30 In the same period, Hainanese servants could command between $20 and $35 per month.Footnote 31

The predominance of Hainanese men in domestic service is partly explained by the tendency for occupations in colonial Singapore to be organized according to dialect group. It was also a consequence of familial patterns of migration, with some domestic servants having followed in the footsteps of male relatives.Footnote 32 The cohesiveness of Singapore's Hainanese servant class was fostered by their membership of the Hainanese kongsi, which colonial officials labelled a “secret society”.Footnote 33 The kongsi helped men find work, played a role in setting standards for working conditions and wages, assisted in the event of unemployment or retirement, and occasionally facilitated (or threatened to facilitate) collective action on behalf of domestic workers.Footnote 34

One area in which the Hainanese kongsi asserted its power was in relation to the campaign for servant registration. Calls for the government to regulate the domestic servant population had been a feature of the political landscape since the 1880s. Between 1911 and 1913, British residents of Singapore (supported by the local press) organized a concerted campaign calling for servant registration. They wanted a system whereby employers were provided with the personal and (potentially) criminal histories of prospective Chinese servants. While a bill for servant registration was passed by the Legislative Council in 1913, it ultimately did not come into force due to the combined threat of mass-strike action facilitated by the Hainanese kongsi and a lack of will on the part of government to enforce the legislation.Footnote 35

By the late 1920s, the nature of the domestic workforce was changing. Indoor domestic work gradually became the domain of Chinese women immigrants, referred to as maijie or “black-and-white amahs” (a reference to the colour of their uniforms), who gradually displaced the Chinese houseboys of the previous era.Footnote 36 By 1931, domestic service had become the most popular occupation for Chinese women in Singapore and, by the 1940s, female domestics constituted seventy per cent of the workforce.Footnote 37 Where men were employed as private servants they tended to be confined to outdoor tasks as gardeners or drivers.Footnote 38 The decline of male servants in private households in Singapore was part of a slow process of feminization of domestic labour across the Asia-Pacific region during the 1930s.Footnote 39 In contrast to private service, however, men continued to be employed in domestic work in hotels, clubs, and bars well into the 1940s.Footnote 40

The available evidence does not provide a clear picture of the frequency of violence within the domestic service relationship in Singapore. In terms of the everyday experiences of Chinese men working as servants between 1910 and 1939, the acts of intense violence studied in this article were not the norm. Murders by stabbing and suffocation, causing grievous hurt by bludgeoning victims, suicides and attempted suicides by swallowing acid – the evidence suggests that these were exceptional events. The lack of reported violent crime reflects the larger patterns of crime in Singapore, where larceny rather than assault or murder was the most common chargeable offence committed.Footnote 41 Certainly, when it came to servants, theft was regularly reported in the local newspapers.Footnote 42 At the same time, however, oral histories and memoirs from domestic servants and their employers in colonial Singapore suggest that physical violence, sexual violence, and the threat of violence were commonplace,Footnote 43 as they were in other colonial contexts.Footnote 44 It is likely that the small number of convictions for such crimes in Singapore is more indicative of underreporting, rather than an absence of violence.

This article does not aim to understand how central a role violence played in the domestic service relationship. Rather, I am interested in what three murder convictions can tell us about the “social materiality” of domestic workers’ lives.Footnote 45 The murder of Sarah Liebmann and Emil Landau in 1918 occurred at a modest hotel in downtown Singapore. The stabbing death of Wong Chee in 1925 took place at a Japanese shipping company mess, located on the city end of Orchard Road. Teo Chye Neo was murdered at her home in the Straits Chinese suburb of Geylang in 1933. The information generated by the colonial state, in terms of investigating these crimes and convicting and sentencing those responsible, can be mined for evidence of the diverse working and social lives of Chinese male servants. By reading this material against the grain, we catch glimpses of how servants moved around the city, where they lived, where they slept, what they did in their leisure time, and the factors that resulted in these workers becoming victims, perpetrators, and witnesses of violent crime.

These cases also provide insight into the experience of domestic workers within Singapore's criminal justice system. In Singapore, the jury system was adopted for criminal cases only and operated (as in Hong Kong) according to English legal principals. However, while in England twelve jurors were required to sit on criminal cases, in Singapore only seven were required and a mere six in Hong Kong.Footnote 46 Another crucial difference from the English system was that verdicts were determined by a majority decision, even in capital cases. In England, a unanimous verdict from all twelve members of the jury was required in all cases. In Hong Kong, a unanimous discussion was required for capital cases.Footnote 47

As Christopher Munn has illustrated in relation to Hong Kong, the colonial court system was set up in a way that made it easier to convict those accused of serious crimes than it would have been in England. In addition, the racialized and class prejudices that were ingrained within the legal system tended to result in harsh sentences for Chinese workers.Footnote 48 Chinese workers were also disadvantaged by the fact that the court system operated on the basis of the English language. The court interpreter had the potential to “influence the course of the trial” in ways that did not necessarily result in just outcomes.Footnote 49 The three murder cases examined here cannot be taken to be representative in terms of the operation of Singapore's legal system. Nonetheless, they indicate that Munn's findings in relation to Hong Kong may also hold true for Singapore.

Chinese lawyers were employed in Singapore from the 1890s and juries included adult men from the “European”, Chinese, Malay, Indian, and Eurasian communities.Footnote 50 However, for important trials (such as murder trials), “special juries” were established with jurors selected on the basis of “superior qualifications in terms of property, character or education”.Footnote 51 While the names of the jurors were not provided in the press accounts of the trials, they were likely of middle- or upper-class origin. Judges in Singapore were members of the British ruling elite.Footnote 52 In this context, it is not surprising that all three cases examined in this article led to death sentences, despite each of the accused pleading “not guilty” to the charge of murder. While the jury decision was unanimous in the Liang case, the verdicts were six to one in relation to both Ee and Yeo.

HOTEL SERVANTS AND THE GLOBE HOTEL MURDERS OF 1918

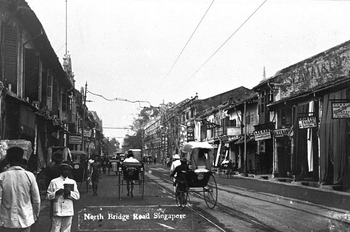

The Globe Hotel, where Liang Ah Tee murdered Sarah Liebmann and Emil Landau, was located on North Bridge Road in the downtown area of Singapore. The section of North Bridge Road on which the hotel was situated ran parallel to Victoria Street and Beach Road. This was a crowded urban area in which low-class brothels and opium houses were common.Footnote 53 They were patronized by the Chinese workers who lived in downtown Singapore, often residing in shop houses that combined work and residence.Footnote 54 The area around Victoria Street and North Bridge Road in particular was dominated by rickshaw workers and their lodgings (Figure 2).Footnote 55 Liang himself had previously worked as a rickshaw puller before taking up a position as a bar boy at the Globe. He resided with other rickshaw men at 65 Bain Street, only 250 metres from the hotel.Footnote 56

Figure 2. North Bridge Road Singapore, 1910s.

Lim Kheng Chye Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore. 19980005879–0017.

While the Globe Hotel might have been located in a somewhat disreputable area, Liebmann and her establishment were represented favourably in the local English press. The Straits Times, the mouthpiece of the British elite of Singapore society, described Liebmann as a “good sort” who “did not have a single enemy”. The hotel, fraternized largely by visiting sailors, was praised as:

[…] a well conducted bar, the proprietress being a “stickler” for quiet behaviour on the premises. She always saw that the sailors, naval and mercantile, left her premises without having had too much to drink and there was always the attraction of some music to keep the men happy.Footnote 57

The positive description of Liebmann in the press is somewhat surprising considering that she was a single European woman and the owner of a hotel. European “barmaids” were sometimes portrayed as a threat to colonial morality and authority.Footnote 58 Liebmann's respectability was perhaps related to her status as a widow and her class position. She was fifty-nine and had lived in Singapore for six years, having moved to the city following the death of her Russian husband in Penang. Liebmann and her elderly lodger, Landau, were both Austrian Jews and were part of the second wave of Jewish migration to Singapore between 1881 and 1914.Footnote 59 The Jewish community was a socially diverse one, with Liebmann and Landau part of the well-to-do commercial class.Footnote 60

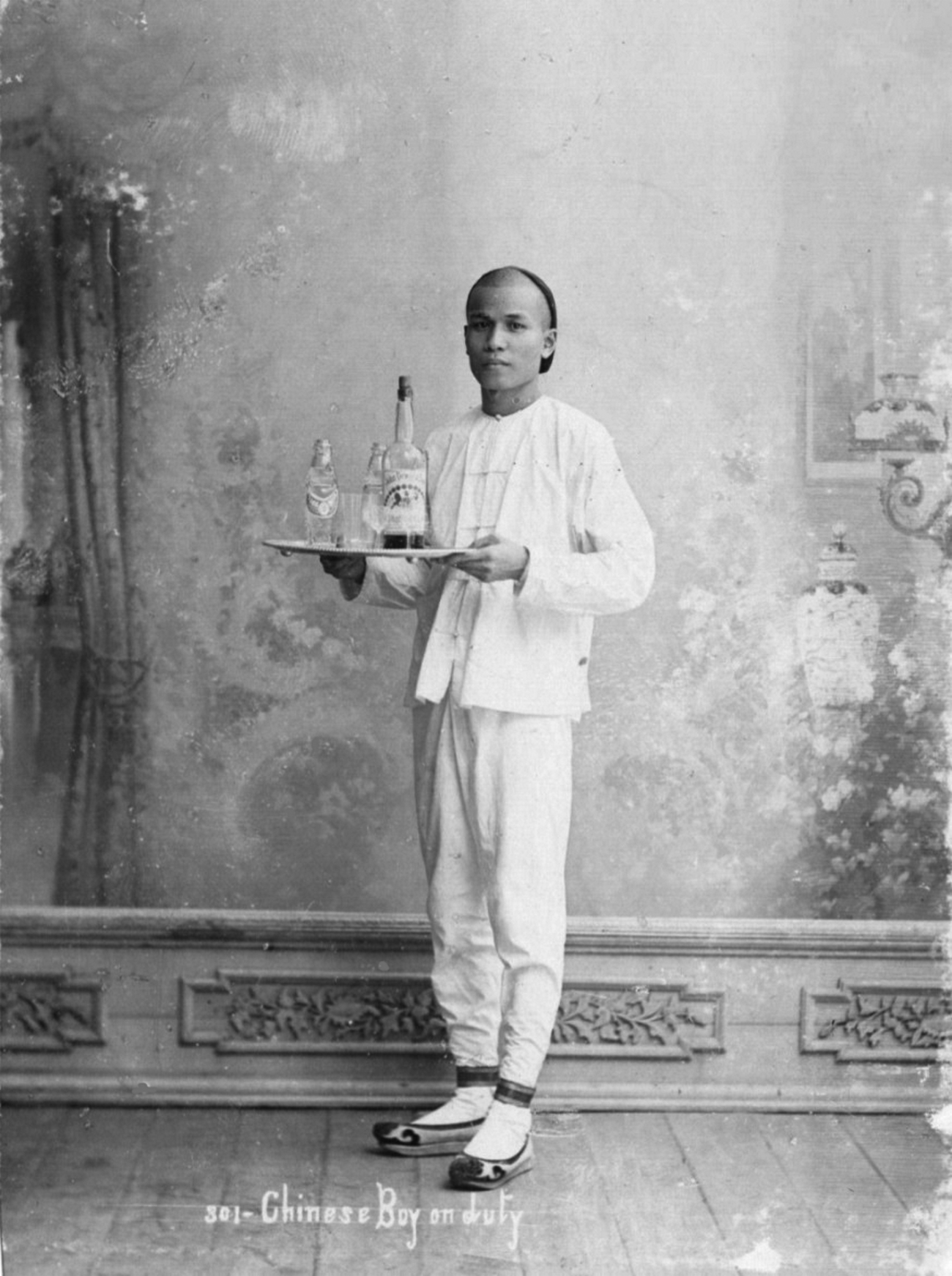

While no specific details about Liang's personal history are provided in the criminal archives, he was typical of Hokchia migrant men who, as late arrivals to Singapore, tended to take up the least sought after occupations, such as rickshaw pulling.Footnote 61 Numerous photographs and postcards featuring rickshaw workers, such as Figure 3, are suggestive of the hard physical labour that the job involved and the limited returns that it provided. Liang's lowly status is further demonstrated by his meagre world possessions, which the police detailed following a search of his dwelling. As was common for men of the rickshaw puller class, Liang owned one box of possessions that was stored under his bed in the small room he shared with other men.Footnote 62 In addition, he owned, according to Detective Inspector Alfred Lancaster, “an old hat” and “a bundle of clothes hanging on a nail over the accused's bed” and a pair of slippers.Footnote 63

Figure 3. Postcard of a rickshaw puller from Singapore published by Max H. Hilckes, c.1910.

Courtesy of the National Archives of Singapore, 19980005094–0107.

The opportunity for Liang to move up the social ladder and become a hotel servant was presented by his roommate and friend, Ah Lay. Ah Lay had been working at the Globe for a number of years. However, sick with an undisclosed illness, he was unable to continue his job and asked Liang to take it over.Footnote 64 Chinese domestic workers were regularly recruited through word-of-mouth, with jobs often passed from one friend or family member to another.Footnote 65

While it might have been a step-up from being a rickshaw “coolie”, Liang described his mere ten days of working life at the Globe as unhappy ones. In his original statement of confession (written with the assistance of a police translator), he maintained that he had murdered Liebmann after she abused him. As he put it:

On the night of August 25, I was asked by the deceased woman to fetch some liquor and I brought the wrong stuff. She abused me and told me that I could not do my work. At eleven o'clock the shop was closed and I told the deceased woman that I could not come the next day. She got angry and struck me and then I hit her with a peace [sic] of iron on the nose and she fell down. I then strangled her with a piece of cloth.Footnote 66

Liang claimed that he also strangled the eighty-year-old Landau following a violent altercation with the man that night. By the time of the murder trial, however, Liang had retracted his original confession, claiming that his statement to Detective Inspector Lancaster had been made under duress. As Liang put it to Justice Ebden at the murder trial:

[Lancaster] told me if I repeated to the magistrate what I told him he would supply me with chandu cigarettes and other things in prison. He also told me that if I made a statement before the magistrates I would be discharged and called as a witness for the Crown, and Twa Bok would be convicted. I agreed.Footnote 67

Lancester's offer of “chandu cigarettes” suggests that Liang was an opium smoker. This is perhaps not surprising. Working in the downtown area, Liang would have had easy access to opium houses and the majority of Hokchia rickshaw workers used the drug.Footnote 68 While it was portrayed by colonial authorities as a Chinese vice, opium was entirely legal in Singapore at the time. Indeed, by the 1910s, the Straits Settlements government held a monopoly on the sale of the drug, the revenue from which made an important contribution to the government coffers.Footnote 69

Liang's claim of duress also illuminates his broader social circle and the financial pressures that Hokchia men endured. Twa Bok was a rickshaw puller who lived with Liang and Ah Lay at the Bain Street lodgings. Liang claimed that he, Ah Lay, and Twa Bok had discovered the bodies of Liebmann and Landau on the morning after the murder. The three men then took $31.50 (Straits) from the premises, removed a ring from Liebmann's finger, and unscrewed the earrings from her ears.Footnote 70 The money was found during the initial search of Liang's room by Lancaster. The jewellery was only located after Liang himself suggested Lancaster return to the Bain Street lodgings and search inside his slippers.Footnote 71 Ah Lay died during the course of the trial and was unable to provide a statement. Twa Bok, however, maintained that he was not involved with the theft and had tried to persuade Liang against it.Footnote 72

Considering the small amount of money and goods that were taken, a financial motive for double murder does not seem to be all that convincing. However, the prosecution asserted that Liang had envisioned a far greater monetary reward. The hotel safe contained $3,850 and the three men had allegedly tried to prise it open and, when that proved impossible, they took it from the premises.Footnote 73 For the jury, this was a compelling motive. They unanimously declared Liang guilty of murder after only five minutes of deliberation.Footnote 74 When the judge asked the prisoner if he had anything to say, Liang once again asserted his innocence, claiming, “[i]f I committed the murder I would have run away […] I would not have gone back to work the next morning”. An unmoved Justice Ebden donned the black cap and passed a sentence of death.Footnote 75 For his part in the crime, Twa Bok was arrested by police on a banishment warrant and soon after removed from the colony.Footnote 76

In the press coverage of the murders, one writer, using the pseudonym “A Hylam”, noted that Liang was “not a Hylam, but a Hokchia” and that “Hylam” (Hainanese) “boys” would “never commit this kind of hideous crime”, in part because the salaries they received were much more generous.Footnote 77 In some cases, Hainanese commanded double the wage of Hokchia servants.Footnote 78 While the writer was quite correct in drawing attention to the very different conditions of employment for Hainanese men in elite homes and high-class hotels, the capacity for murder was not (of course) determined by ethnicity. Nor did all Hainanese domestic workers enjoy high wages and good working conditions, as the Onan Road Murder of 1933 illustrates.

WORK AND DEATH IN A STRAITS CHINESE HOUSEHOLD: THE ONAN ROAD MURDER, 1933

Not far from downtown Singapore, Geylang, in the north-east of the city, was a traditional enclave for the Malay and Arab communities, with the land dedicated to the cultivation of coconut plantations. In the 1920s and 1930s, the district underwent major development as roads, shophouses, and terraces began to be established. At that time, significant numbers of Straits Chinese families moved into the area.Footnote 79 It was in one such household that a young Hainanese servant, Yeo Tin Keng, was employed by a Straits-born Hokkien couple in 1933. Yeo was the only servant employed within the household on 40-A Onan Road, a sandy lane off Geylang Road.Footnote 80 On the morning of 22 June, after his master had left for work, fourteen-year-old Yeo stabbed to death his mistress, Teo Chye Neo, in front of her five-year-old daughter. The screams of Teo alerted passers-by and while Yeo attempted to flee, he was captured and taken to Katong police station. The twenty-seven-year-old Teo, who was pregnant at the time of her death, died at the scene. She was found “lying in a pool of blood” with at least ten stabs wounds to the face and neck.Footnote 81

Unlike the previous murder studied in this article, the inquest records for the Onan Street murder are not held in the National Archives of Singapore. The Coroner's Court Master Book includes only a short reference to the case, with the cause of death described as shock due to stab wounds and a finding of murder recorded.Footnote 82 The case was, however, reported in considerable detail in the newspapers.

Considering that Yeo murdered a pregnant woman, and did so in front of her young daughter, the measured way in which the case was reported is surprising. The articles that described the murder and Yeo's trial focused on his young age of fourteen and the systematic abuse that he experienced in the Onan Road household. Neighbours interviewed during the murder trial maintained that Teo was “a woman of violent temper” and that she had frequently abused and scolded Yeo.Footnote 83 Teo's five-year-old daughter was also interviewed at the trial and she confirmed that Yeo was subjected to daily abuse, including on the day of the murder when her mother slapped him in the face. In his own (translated) account, Yeo maintained that:

The deceased used to scold and abuse me and hit me with a piece of wood, clogs and shoes. If she found a little dust on the chair, she would abuse me […] Sometimes she spat on me. I was struck on the arms and forehead with a piece of firewood.

On the day of the murder, Yeo claimed that Teo had hit him because the floors were not clean.Footnote 84 He tried to return to his job but his mistress continued beating him and kicking him before grabbing a knife and running at him. According to Yeo's account, a struggle ensued and he stabbed her in the face before she fell on the knife. He panicked, took the backdoor key from her bedroom, opened the door and ran.Footnote 85

It was not entirely uncommon for Chinese men who had been “reprimanded”, physically threatened, or “abused” to retaliate with violence.Footnote 86 Yeo suffered not only from daily abuse, but also from social isolation. He was locked in the house and prevented from leaving to socialize with his friend and his brother, who also resided in Singapore.Footnote 87 For Chinese domestic workers, visiting family members or frequenting coffee houses was important in terms of leisure.Footnote 88 Such outlets allowed Chinese men to escape the “disciplinary gaze of their employer”, providing opportunities for them to socialize in groups, complain about the demands of the job and seek emotional support.Footnote 89

While Hainanese hotel workers enjoyed the protection and camaraderie of the Hainanese kongsi, Yeo had been recruited informally. He came to work for Teo after she approached him at the Katong Market with an offer that was a $2 increase on the $4 a month salary he received in his previous job as a servant at the Joo Chiat English School. This was a very small wage compared with the $20 to $30 dollars a month that Hainanese servants in other households and hotels were commanding. In any case, in the three months that he was employed at Onan Street, Yeo claimed that he had received no wages at all.Footnote 90

This case illustrates the degree to which the working conditions of Chinese male servants were unregulated. In their campaigns for servant registration, employers claimed that the lack of governmental regulation left them vulnerable to exploitation and abuse by their Chinese staff.Footnote 91 As Yeo's story suggests, however, domestic workers were perhaps more vulnerable to exploitation than their employers. In light of Yeo's circumstances, his defence Lawyer, Mr Mitter, urged the jury to return a finding of self-defence. The jury members must have found the claims of abuse compelling. They deliberated on the verdict for over an hour, with the foreman asking for clarification from the judge as to “how long a time would be implied in the word ‘sudden’ as regards to the question of sudden provocation”. While the jurors were sympathetic, they found Yeo guilty of murder by a verdict of six to one. As Yeo was underage, he was sentenced to “be detained pending His Majesty's pleasure”, at which point he disappeared from public discourse.Footnote 92

The first two cases of murder examined in this article considered servant violence towards their employers. The final case to be considered, the Orchard Road Murder of 1925, involved a conflict between two domestic workers.

THE ORCHARD ROAD MURDER OF 1925: VIOLENCE BETWEEN SERVANTS

On 5 November 1925 at around seven o'clock in the evening, a thirty-year-old Hokchia tukan ayer (water carrier) by the name of Ee Ah Lak murdered Wong Chee, a Hokchia houseboy. The men had worked and lived together for two years within the mess of the NYK Japanese shipping company located on 106 Orchard Road. At the northern end of Orchard Road lay the suburb of Tanglin, which encompassed the Botanical Gardens and was home to the British colonial elites.Footnote 93 Here, they resided in leafy Anglo-Indian bungalows with their household staff living onsite in servants’ quarters.Footnote 94 Numerous servants also lived within servants’ quarters in the mansions of wealthy Straits Chinese and overseas Chinese located in the vicinity of Orchard Road on illustrious streets such as Devonshire Road, St Thomas Walk, Scotts Road, and Emerald Hill.Footnote 95 Rather than being surrounded by bungalows and mansions, however, the NYK mess house was at the south-eastern end of Orchard Road, a busy commercial area (Figure 4). The mess house was within walking distance of an area called Dhoby Ghaut. Here, Indian laundry workers (dhobies) worked in commercial laundries, washing clothes using water from Stamford Canal.Footnote 96

Figure 4. Postcard of Orchard Road towards the direction of Dhoby Ghaut, Singapore, c.1920.

Robert Feingold Collection. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore, 19980005107–0086.

The murder that took place in the NYK residence was a vicious one. Ee stabbed nineteen-year-old Wong twenty-one times in the abdomen, chest, and extremities with a dual-edged Japanese knife. Shortly after the murder, Ee presented himself to the Orchard Road Police station. Dressed in bloody clothes and carrying the knife, he confessed to the crime. The police rushed to the NYK mess and arranged transport for Wong to the Tan Tock Seng Hospital. By the time he arrived at the hospital, however, Wong was unconscious. He died of his injuries shortly after.Footnote 97

The first police officer who arrived at the scene of the murder was a Malay sub-Inspector. He interviewed the mortally wounded Wong in Malay about what had happened. According to this account, Wong claimed that he had asked Ee to return twenty dollars that he had lent him some weeks ago. In response, Ee became angry and stabbed Wong. The other houseboy and cook employed in the mess confirmed, as did Wong's mother, that Ee owed Wong money.

Chinese labour migrants to Singapore typically followed the lead of male family members, such as brothers and uncles.Footnote 98 Wong was somewhat unusual for a Chinese migrant in that his mother lived in Singapore. She resided on Victoria Street, about a twenty-minute walk away from the Orchard Road mess house. While other Chinese men employed as domestic workers in Singapore remitted money to China to support relatives, Wong supported his mother in Singapore.Footnote 99 In her interview at the inquest, Wong's mother confirmed that her son had lent Ee money, but disputed the amount. She explained that Wong usually gave her fifteen dollars a month, which was three quarters of his monthly wage. In the previous month, however, he had only given her ten dollars, having lent Ee the rest.Footnote 100 It is true that tensions arising from debts owed or threats to financial stability drove domestic workers to engage in violent acts in other households.Footnote 101 In the case of the Orchard Road murder, however, the money that Ee owed Wong does not seem to have been the catalyst for the stabbing.

The cook, the houseboy, and Wong's mother maintained that Wong had only limited Malay and that this may have resulted in a miscommunication with the attending police officer. They explained that Ee and Wong were good friends, who always socialized together and had shared a room for the past eleven months. All four of the servants employed in the household were close, having migrated from the same district in China.Footnote 102 The houseboy, who had talked to Wong before he died, maintained that the conflict arose when Ee asked to share Wong's bed and Wong refused. In the small room that they shared, Wong had an iron bed and a mosquito net. Ee had only a green canvas bed, the legs of which were broken.Footnote 103 In his testimony at the inquest, Ee confirmed this basic account but added that Wong had told him he could no longer sleep in the same room and had thrown his pillow and blankets on the floor. Wong (Ee claimed) then grabbed the knife and attempted to stab Ee. Ee wrestled the knife from him and struck him with it blindly.Footnote 104

It may have been the lack of personal space and the basic furnishings of the servants’ quarters that proved a catalyst for violence. It is not clear if Ee's employer (referred to in the records as “the tauke” (towkay/boss) provided him with the canvas bed or if Ee had purchased it himself. What is clear is that Ee could not afford to have the bed repaired. As a water carrier, Ee earned only $15 per month and was the most easily replaced and least skilled of the household staff. A sense of humiliation and injustice certainly comes through in Ee's account of the murder. This might explain the level of rage involved in the killing, with four stab wounds in Wong's chest delivered with enough force to puncture the lungs.Footnote 105

There is another possibility for motive. The intimate setting of the murder in the bedroom and the accounts that described the men as friendly and constantly in each other's company may suggest that this was an intimate relationship turned sour. In China, unlike the European context, homosexuality was tolerated at least up to the Chinese Revolution of 1912.Footnote 106 Chinese “houseboys” in Singapore, like those in French Indochina, were depicted by European colonists as being open to homosexual liaisons.Footnote 107 Yet, the stigma and secrecy that surrounded homosexuality, and the threat of prosecution for engaging in sodomy, has ensured that definitive proof of same-sex relationships in colonial Singapore is hard to come by.Footnote 108 The possibility that Ee murdered Wong due to the breakdown of an intimate relationship was not one raised in the press or the legal documents. In contrast to the Wong murder case, in two other criminal cases involving Chinese male servants, journalists and lawyers were quick to suggest that the rejection of sexual advances by Chinese women had driven the men to engage in violence.Footnote 109

Regardless of the motive, Ee admitted to stabbing Wong but maintained innocence in relation to the charge of murder. In defending his client at the murder trial, which took place on 25 to 26 January 1926, V.D. Knowles argued that provocation by Wong ensured Ee had “entirely lost control of himself”. Knowles urged the jury to find him guilty of the lesser charge of homicide.Footnote 110 Only one juror seems to have found that argument convincing, with the remaining six finding him guilty of murder. Justice Deane concurred with the majority verdict and sentenced Ee to death.Footnote 111 The Coroner's Court records describe his death by judicial hanging three months after the murder of Wong, on 9 February 1926.Footnote 112

CONCLUSION

The three cases of murder explored in this article challenge us to think about domestic service in new ways. The Globe Hotel murders, the Onan Street murder, and the Orchard Road murder illuminate the diverse situations in which Chinese male servants lived and laboured. Rather than the traditional paradigm of elite white employers and Asian servitors within private homes, we see men defined as servants working in low-class hotels, company messes, and middle-class Straits Chinese households. The stories explored here build on our existing knowledge of the troubled encounters between masters and servants. They also bring to light the personal lives and struggles of domestic workers. The three cases examined in this article highlight Chinese men's personal and family relationships, their struggles to eke out a living, and the material conditions in which they lived.

This article represents a first step towards analysing crimes committed by Chinese male servants in order to document the experiences of a group of workers about which little is known. Chinese male servants laboured largely outside of governmental regulation. The rare cases in which they were convicted of crimes brought them into contact with the power of the colonial state in an unprecedented way. The rich archival materials generated by these moments of regulation provide glimpses into the experiences and perspectives of these men. They also shine a light on the broader social worlds of the residents of colonial Singapore as well as the way in which the justice system operated. Further analysis of the Globe Hotel, Onan Street, and Orchard Road murders using the Chinese-language press, alongside analysis of other serious and petty crimes for which Chinese male servants were convicted, has the potential to shed further light on this group of workers and on the nature of everyday life in the cosmopolitan port city of Singapore.