Coming off the back of an electoral campaign, each new administration tends to overplay its “break” with its predecessors and to emphasize the aspects that represent change rather than continuity. In few transitions was this truer than when Kennedy replaced Eisenhower: the New Frontier and its youthful President, the first one born in the twentieth century, replacing the “old” guard with a new vision for the projection and use of American power in the Cold War.1 In his inaugural address, Kennedy picked up on this generational theme in announcing, “let the word go forth from this time and place, to friend and foe alike, that the torch has been passed to a new generation of Americans – born in this century, tempered by war, disciplined by a hard and bitter peace, proud of our ancient heritage.”2

The journalist Theodore White captured the mood of expectation in describing “an impatient world wait[ing] for miracles” from the new President, who “had been able to recognize and distinguish between those great faceless forces that were changing his country and the individuals who influenced those forces. For if it is true that history is moved on by remorseless forces greater than any man, it is nonetheless true that individual men by individual decision can channel, or deftly guide, those impersonal forces either for the good or to disastrous collision.”3

However, for all its promise of change, many of the ideas that Kennedy articulated for economic and foreign policy in an “impatient world” predated his arrival in the Oval Office. Just as the bureaucratic “revolutions” that McNamara undertook at the OSD fell within a lineage of change, a gradual process of bureaucratic transformation that preceded his tenure, so too did many of the Kennedy administration’s foreign policy ideas. On economic policy as well, a great deal of continuity existed between Eisenhower and Kennedy. Even if the administration had brought in prominent left-wing economists, leading some to conclude that, “Kennedy’s economic advisors … were Keynesian expansionists, committed to full employment and economic growth, less concerned than their Republican counterparts about budget deficits and inflation,”4 in reality, the President was cautious and reluctant to move on their recommendations.

Moreover, although Kennedy had chastised Eisenhower for “putting fiscal security ahead of national security”5 during the election campaign, once in office, he too was concerned that international responsibilities were beginning to weaken the economic foundations of the United States. World War II and the ensuing Cold War created new treaty obligations and defense installations across the world that produced persistent balance of payments deficits. As a result, a central but overlooked part of Kennedy’s foreign policy and, in turn, of his defense policy was that other countries should bear a greater share of the burden for their own security.6 Economic concerns conditioned his, and McNamara’s, strategic choices in Vietnam and elsewhere.

Notwithstanding a high degree of continuity and the fact that President Kennedy’s views on national security and defense policy evolved in office, a number of philosophical threads underpinned the new administration’s defense policy and differed in emphasis from its predecessor’s. First and foremost, Kennedy shifted away from a policy that focused on nuclear forces and toward flexible response, which allowed for a broader foreign policy view and the deployment of both military and non-military tools to allow cross-government, coordinated interventions on a broader spectrum of international situations, especially in the developing world. The administration pledged to experiment with new ways of projecting US power after decades during which the projection of US power had become increasingly defined in military terms.

The inaugural address set the tone and ended on a measured note, a message to other countries that they had to make sacrifices and share the burdens of protecting their freedom. Contrary to popular belief, the speech was not “bellicose and filled with soaring hubris,”7 and when President Kennedy said that “we shall pay any price, bear any burden … in order to assure the survival and success of liberty,” the operative we was not just the American people but also the people of the world.8 Although he suggested a clear focus on providing aid to the developing world and to the “peoples in the huts and villages of half the globe,” Kennedy alerted that the administration would merely “help them help themselves.” Furthermore, while he accepted the logic of nuclear deterrence, Kennedy cautioned that both the Soviet Union and the United States were “overburdened by the costs of modern weapons” and threatened by the danger that “science [might] engulf all humanity in planned or accidental self-destruction.”9

Nevertheless, the address established a revised intellectual framework, new priorities for and a redefinition of international security. As a result, it spurred drastic changes at the OSD, which moved to align defense capabilities to meet the new objectives. Where Vietnam was concerned, this included the Special Group on Counterinsurgency, ISA at the OSD and McNamara’s private office. Each played a preeminent role in the articulation of Vietnam policy and eventually in the withdrawal plans initiated in the spring of 1962.

If Kennedy was keen for allies to pick up a greater share of the costs associated with their defense, it was also because he had set in motion a shift away from nuclear power that, in the short term, was inevitably very expensive. Paradoxically, as Yarmolinsky later explained, it was precisely because the budget was expanding for a time that the administration could push through its necessary reforms. Cutting force levels and the budget at the same time was unfeasible – it “tend[ed] to freeze attitudes and to heighten institutional jealousies” – even if, in the longer term, a significant budget cut was “highly desirable.”10

Strategically, two ideas inspired the move away from Eisenhower’s national security policy, which was centered on nuclear deterrence. First, although they were reticent to make these ideas public, Kennedy and several of his closest colleagues believed that nuclear weapons and their use were inherently immoral. Second, reflecting the mood of the times, they felt nuclear deterrence specifically, and the Cold War competition more generally, had created conditions in which lower-level conflict had become more likely. Accordingly, defense policy was overhauled to respond to a broader set of contingencies and particularly situations of low-level, guerrilla-type conflict in newly independent states where the Communist threat seemed on the rise, notably in Laos and Congo. The Defense Department played a key role in coordinating relevant tools across government for these types of conflicts, principally by expanding the administration’s aid program and strengthening its own capabilities, including by reinforcing the Army’s Special Forces.

From the outset, the administration adopted a moralistic tone about nuclear weapons.11 In September 1961, once again building on the rhetoric of his inaugural address, Kennedy spoke to the issue of nuclear disarmament at the UN General Assembly, saying that nuclear weapons threatened to turn the “planet into a flaming funeral pyre” and that “weapons of war must be abolished before they abolish us.”12 At other times, religious undertones pervaded his speeches on the issue. For instance, in his June 1963 commencement address at the American University, he argued for a relaxation of the arms race, saying, “For, in the final analysis, our most basic common link is that we all inhabit this small planet. We all breathe the same air. We all cherish our children’s futures. And we are all mortal.” Using quasi-biblical language, he implicitly confronted the reluctance of the JCS to begin disarmament talks,13 by adding: “Surely this goal is sufficiently important to require our steady pursuit, yielding neither to the temptation to give up the whole effort nor the temptation to give up our insistence on vital and responsible safeguards.”14 Privately, Kennedy held even stronger reservations and questioned whether nuclear weapons could ever be useful or if they could ever achieve what were ultimately political objectives.15

Similarly, in April 1963, Alain Enthoven, a key figure in the formulation of nuclear policy, wrote an article in a Jesuit publication describing how the administration’s shift in policy fit within the moral codes of the just war tradition. Enthoven wrote: “Now, much more than in the recent past, our use of force is being carefully proportioned to the objectives being sought, and the objectives are being carefully limited to those which at the same time are necessary for our security and which do not pose the kind of unlimited threat to our opponent in the Cold War that would drive them to unleash nuclear war.”16 In other words, by developing a more flexible force structure, the administration was laying the groundwork for a more proportional and discriminate response to political crises than a posture relying primarily on nuclear weapons allowed.

McNamara echoed the President’s views in his own speeches, but in a way that reflected both the practical steps that his department had undertaken to lessen the United States’ reliance on nuclear weapons, and his concerns that allies, especially France, were increasing the likelihood of nuclear escalation by developing their independent nuclear force. McNamara made two particularly controversial and landmark speeches: one on May 5, 1962, to the NATO Ministerial Meeting in Athens and a distilled version of the same speech the following month in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Both speeches outlined the administration’s general approach to nuclear strategy, but whereas the former was classified and only for NATO Defense Ministers, the latter was a public address aimed at “talking to [unresponsive] NATO Allies through the press.”17

In Ann Arbor, McNamara said, “Surely an Alliance with the wealth, talent, and experience that we possess can find a better way than extreme reliance on nuclear weapons to meet our common threat.” He reiterated the idea set out in the inaugural address that the projection of US power had to rely on more than military power, let alone nuclear power. He explained that “military strength is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for the achievement of our foreign policy goals” and added that “military security provides a base on which we can build free world strength through the economic advances and political reforms which are the object of the President’s programmes, like the Alliance for Progress and the trade expansion legislation.”18

Moreover, one of the main ideas in McNamara’s speeches and in Enthoven’s article was that the United States had enough, even perhaps too many, nuclear weapons.19 Although the administration, and the JCS in particular, had many reservations about the viability of disarmament talks and the 1963 Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, McNamara nevertheless argued that it was important “to lay groundwork” and that the administration could “never know [how useful these initial steps would be] in future.”20

McNamara and his colleagues’ speeches were drafted in a way that reflected the delicate nature of the changes within the Defense Department and with an eye toward their inevitable international impact. According to his main speechwriter, “we began each talk of this kind by pointing out our enormous superiority” before moving on to presenting the potentially controversial policy changes.21 The primary purpose was not to reassure the allies but the Chiefs. The administration was declaring that in spite of the shift in policy, it would not cut their nuclear arsenal drastically. Yarmolinsky recalled that the Chiefs had framed “the terms of the debate” in such a way that such cuts were impossible.22

Overall, as they did with many of McNamara’s changes, the Chiefs lodged wholesale resistance to almost every aspect of the reforms to nuclear strategy. They resisted disarmament talks and the test ban treaty on the basis that they lacked adequate verification systems. More alarmingly, they refused to share their main nuclear contingency plan, the so-called Single Integrated Operational Plan, or SIOP 63, with Defense Department staff or even with the President himself, offering only to brief McGeorge Bundy on its contents.23 They also resisted Defense Department efforts to integrate flexible response thinking into their planning.24 Even Maxwell Taylor resisted reform once he became Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in October 1962. In a taped conversation with President Kennedy in December 1962, he stated, “As you know, in the past I’ve always said, we probably have too much … But sir, I would recommend staying with the program essentially as it is.”25

By 1962, faced with resistance from the Chiefs as well as from European allies who were reluctant to invest in the conventional forces required for a more flexible nuclear strategy, the administration discretely settled on a policy of mutually assured destruction (MAD). In part, the policy was a logical corollary of McNamara and his colleagues’ conclusion that “nuclear warfare itself was suicidal” and therefore that the United States needed a “nuclear component sufficient to serve only as a deterrent.”26 Above all, it was the product of economic concerns. The administration toyed with nuclear policy alternatives, notably by investing in civil defense projects and by studying the possibility of a counterforce strategy, namely attacking Soviet nuclear sites before they could launch missiles. Both were designed to limit damage to the United States and thus increase survivability in the event of a nuclear exchange. McNamara ultimately considered both to be cost-prohibitive and so they were eventually axed. As one scholar has noted, “the downward revision of strategic goals was … motivated in large part by a desire to put a lid on defense spending.”27

In reality, Kennedy’s nuclear policy was not radically different from Eisenhower’s, which is not to say that flexible response was, as some have contended, entirely a “myth.”28 The prospect of nuclear war repulsed both Kennedy and Eisenhower, but for Kennedy, this implied the need to reshape defense policy and its tools so that the United States could respond to conflicts across the spectrum of violence from the lowest level up to and including nuclear war.

The idea that the United States should be prepared for lower-level conflict, especially in the developed world, had intellectual precedents in the Eisenhower administration.29 Maxwell Taylor, Eisenhower’s Army Chief, had fallen out with the administration over the New Look strategy and had provided much of the intellectual foundation for flexible response in his book The Uncertain Trumpet, which was published with great fanfare in 1960.30 Elsewhere, others such as then Undersecretary of State for Economic Affairs C. Douglas Dillon recalled that, in the last two or three years of the Eisenhower administration, he and his State Department colleagues had “push[ed] hard” for limited war capabilities. However, not until Kennedy’s election did his “minority view,” which the new President shared, take center stage.31

The Kennedy administration was predisposed to take the contingency of US involvement in lower-level conflicts seriously, but this gained a sense of urgency in January 1961. At that time, Chairman Nikita S. Khrushchev made his landmark “national wars of liberation” speech in which he predicted that local insurgencies in the developing world were more likely in a thermonuclear world and where he stated that Marxists had “a most positive” attitude toward “such uprisings.”32 Khrushchev’s speech made a deep impression on the Kennedy administration: one joint State-Defense report from December 1961 noted that the administration recognized “changing political conditions around the world, shifts in the nature and probability of threats” and especially that the “likelihood of indirect aggression seems much greater during the 1960s than that overt local aggression.”33

McNamara, in an address to the National Bar Association in February 1962, described Khrushchev’s speech as possibly “the most important statement made by a world leader in the decade of the 60’s.” In a lengthy analysis of Khrushchev’s words, he explained: “What Chairman Khrushchev describes as wars of liberation and popular uprisings, I prefer to describe as subversion and covert aggression. We have learned to recognize the pattern of this attack. It feeds on conditions of poverty and unequal opportunity, and it distorts the legitimate aspirations of people just beginning to realize the reach of the human potential. It is particularly dangerous to those nations that have not yet formulated the essential consensus of values, which a free society requires for survival.”34

In responding to this threat, Kennedy argued that the United States’ image abroad needed an overhaul and recommended a full set of strategies ranging from appropriate military interventions to well-designed aid and development efforts.35 To this end, delivering on a campaign promise, he established the Peace Corps under the leadership of his brother-in-law Sargent Shriver in March 1961 and, in October 1961, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under David Bell, “one of his closest associates.”36 Responding to congressional criticism, USAID consolidated existing and scattered aid programs to encourage a longer-term and more strategic approach to existing aid efforts. The creation of USAID also embodied the administration’s belief that “foreign aid [was] a relatively cheap way of preventing Communist encroachment.”37

In keeping with these changes, McNamara argued before Congress that “a dollar of economic aid is as important as a dollar of military aid,”38 and behind the scenes, he coordinated the Defense Department’s overseas programs closely with USAID, notably in Vietnam, where their budgets were practically fused. Paradoxically, McNamara’s ability to think of his office within the larger scope of government rather than downward to the military services and other bureaucratic interests meant that he weighed heavily on a number of relevant government-wide structures.

At the time, one of the most important cross-government offices for the administration’s stated desire to respond to “wars of national liberation” was the Special Group Counterinsurgency (CI). According to National Security Action Memorandum (NSAM) 124, which set up the Special Group in January 1962, its purpose was “to ensure proper recognition throughout the US government that subversive insurgency (“war of national liberation”) is a form of politico-military conflict equal in importance to conventional warfare” and to ensure the “adequacy of resources” and “interdepartmental programs” to “prevent and defeat subversive insurgency.”39

To this end, the group included a number of military, OSD, NSC and State Department representatives, the director of the CIA and the director of USAID.40 Maxwell Taylor, first as the President’s Military Representative and then as Chairman of the JCS, together with Attorney General Robert Kennedy, headed the group. Although, from a bureaucratic perspective, the Attorney General was an unusual choice for this role, his presence was designed to send a strong signal that the President was the “driving force behind this effort.”41 Roswell Gilpatric, who usually represented the Defense Department on the Special Group (as it was not McNamara’s “dish of tea”) remembered that, “You know, [Kennedy had] read some Marine magazine about Green Beret type of activity, and he felt that when you got away from strictly conventional military or intelligence of State Department activities, there wasn’t any well-coordinated, cohesive direction. And that’s when I think he told his brother he wanted to get him into this thing.”42

At any one time, the group oversaw efforts in a dozen or so countries spread across Latin America, the Middle East, Africa and Asia.43 Asia had always been its first focus: Thailand, Laos and Vietnam had been founding countries in its portfolio, although Latin America superseded them by 1963.44 For each of these countries, the group prepared quarterly Internal Defense Plans, which were a kind of progress report on each country’s efforts to suppress domestic insurgencies or unrest. The group reviewed and assessed the work of relevant US agencies’ work in each of the countries, usually USAID, United States Information Agency (USIA) and civic action programs, which included efforts at building up local military and policing capabilities. Although the most visible aspects of the group’s work were on military and paramilitary capabilities, its focus was primarily on civic action programs. Civic action was a murkier aspect of US foreign policy and had been regarded as marginal within government before the Kennedy administration.45 It involved projects on the boundaries of the different agencies.

The Special Group was particularly active throughout 1962, but by January 1963, after Taylor’s move to the JCS,46 it seemed to fall into disuse, much to the chagrin of Robert Kennedy, who complained that “there are a lot of things that could be done under the proper auspices,” whereas “our present CI operation is most unsatisfactory.”47 His colleagues were even more pointed in their criticism and bemoaned that the State Department could not pick up where Taylor had left off. One wrote: “I assume that the Department of State is still not ready (I am not prepared to say unable) to assume this leadership role.”48

Robert Komer, the NSC’s representative to the group,49 was slightly more positive in his assessment and felt it “performed a real service in pushing, needling, prodding and coordinating” counterinsurgency efforts across the administration.50 Yet by July 1962, he too became frustrated at the State Department’s lack of leadership: “A case could be made that [the Special Group] has already performed its main service, i.e. to get the town moving on CI in the way JFK wants. But I fear that if we scratch the Group now everything will sink back into the usual bureaucratic rut. State, which should be monitoring the CI show, is simply not set up to do it.”51

The Kennedy administration’s counterinsurgency agenda had important budgetary and bureaucratic repercussions for the Defense Department that aggravated its already strained relationship with the services. Marine Corps General Victor Krulak had the frustrating task of overseeing the services’ progress on building counterinsurgency expertise and capabilities and adjusting their doctrines. They reported to Krulak, who was based out of the JCS Staff, and he, in turn, reported to McNamara and occasionally directly to the President. He also participated in the Special Group (CI), sometimes sitting in for Taylor or Gilpatric. Later he recalled that most of the time, despite impressive statistics and a service-wide Joint Counterinsurgency Doctrine, progress was “more volume than value” and “mostly they weren’t doing much.”52

The services resented yet another OSD-led reform agenda but were compelled to go along given the administration’s public commitment to counterinsurgency. Most senior military officials dismissed these efforts as “faddishness” and considered themselves more than prepared to respond to any contingency.53 In part, as far as the Navy and Air Force were concerned, resistance was also rooted in suspicions that the administration’s interest in counterinsurgency was essentially designed to strengthen the Army, which itself had initially resisted involvement in counterinsurgency operations.54 If Eisenhower’s New Look had favored the Air Force and to a lesser extent the Navy budget, it was clear that flexible response favored the Army. Both services regularly lamented the administration’s perceived “Army bias” particularly after the arrival of Taylor, and the administration’s fascination with the Special Forces puzzled them.

In many ways, this early period of the Kennedy administration’s involvement in Vietnam was a “coming of age” period for the Special Forces. Although the Special Forces had been activated in 1952 at Fort Bragg in North Carolina, they were largely dismissed as an esoteric bunch until Kennedy came to power. Their numbers almost tripled between 1961 and 1963.55 The administration’s first budget specifically foresaw “a substantial contribution in the form of forces trained” for guerrilla warfare (see Figure 3.1).56

Figure 3.1 Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara visits the 82nd Airborne Division at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, October 12, 1961. McNamara favored light and mobile Army units, prompting the other services to accuse the administration of having an Army bias.

In addition, the administration maintained a high level of publicity around the Special Forces. The columnist Joseph Alsop, an administration insider, writing just weeks after Kennedy’s inauguration, described an NSC meeting where Kennedy praised the Special Forces as “equal to the nuclear deterrent.”57 Both Kennedy brothers went out of their way to raise the profile of the Special Forces: President Kennedy decreed that they be given their iconic green berets as a “symbol of excellence, a badge of courage, a mark of distinction,”58 and Robert Kennedy famously kept a green beret on his desk.

In his address to the National Bar Association in February 1962, McNamara singled out the Special Forces, though not by name, as a key tool to deal with “wars of national liberation,” which he described as “often not wars at all.” He warned that dealing with these types of situations “requires some shift in our military thinking” and that the Defense Department was “used to developing big weapons and large forces,” whereas it now needed to train “fighters who can, in turn, teach the people of free nations to fight for their freedom.”59

In a speech delivered at the Special Forces training school in Fort Bragg that was initially intended for McNamara, Yarmolinsky explained how the Special Forces fit into flexible response and the need to have forces “across the full spectrum” of conflicts. He explained their special value in the face of guerrilla warfare and subversion, where they had “taken on an importance that was virtually undreamed of only a decade ago.” Significantly, one line was removed from his speech at the last minute that might have had special resonance with Vietnam: “We have no desire to, and few countries would want us to, send large scale American troops to their nations to deal with problems of terrorism and subversion and guerrilla warfare. Nothing could be more inappropriate.”60

In private, Yarmolinsky, who as a leading member of Kennedy’s presidential campaign had been instrumental in creating the idea of the “New Frontier,” went further and explained how “these people are properly New Frontiersmen as much as any Peace Corps volunteer or [US]AID mission member. In a world where force is still necessary, they can make the necessary use of force both understandable and justifiable to the uncommitted people of the world.”61 Thomas Hughes, who became director of INR in 1963 and who worked closely on Vietnam, also saw the Special Forces as a preeminent symbol of the New Frontier and Vietnam as their first project. He explained, “A new breed of Americans, right out of Kennedy’s inaugural address, was being tested in Vietnam.”62

From a bureaucratic perspective, the Special Forces fit tidily into the types of cross-government work that the administration wanted to experiment with and from the Defense Department’s view, with a more cost-efficient strategy whereby the United States could rely on airlift capabilities and rapid reaction forces instead of forward positioning to deal with crisis situations across the world. Yarmolinsky described how “not numbers but quality” mattered most and that the Special Forces showed how a “relatively small body of superbly capable and superbly trained men can provide, and I am sure will provide, an enormous contribution.”63 In addition, capabilities such as the Special Forces held a distinct appeal because they were so adaptable and had a much lighter logistic and support base, and because the Defense Department did not have to finance them entirely.

The Special Forces in Vietnam represented the type of bureaucratic innovations that the Kennedy administration pursued through its Special Group (CI). The Special Forces were deployed under CIA command and ran projects in remote villages where ethnic minorities lived, notably the Montagnard communities. The latter were discriminated against in Vietnamese society and were therefore reluctant to embrace either the Ngo Dinh Diem regime in Saigon or the North Vietnamese communists. Working with other agencies in Vietnam, the Special Forces combined seemingly anodyne activities such as running clinics and offering job training with psychological and propaganda operations as well as programs to arm and train local militias. As one CIA history explained, “they were more than soldiers; they were, in a way, community developers in uniform.”64 From a bureaucratic perspective, the most interesting aspect of these activities is that the executive authority over the Special Forces and civic action programs was not with the Army but with the CIA, in coordination with the ubiquitous ISA.65

The administration’s interest in Special Forces and counterinsurgency was a response to objective international realities about the changing shape of conflict but was conditioned by economic concerns. The same pressures that had encouraged McNamara to settle on a nuclear policy premised on MAD also informed his interest in counterinsurgency programs over traditional military deployments.

Kennedy entered the White House with a sense of economic vulnerability that continued throughout his time in office and colored many of McNamara’s defense decisions. Part of this vulnerability stemmed from slow growth in the US economy and nagging unemployment figures that coincided with Premier Khrushchev’s own economic plan that threatened to overtake the US economy by 1970.66 But especially it came from the balance of payments problem and the threat it posed to the dollar as the international reserve currency. As Kennedy’s economic advisor Seymour Harris explained, “We have now become like all other nations – a nation that has to watch its balance of payments. We were free of that particular responsibility for a long time.”67

Confirming Francis Gavin’s work, and contrary to the conventional wisdom that the balance of payments and gold outflow would not surface as an issue until much later in the decade, the economic historian Barry Eichengreen used data mined from official documents to show that balance of payments concerns had a greater level of saliency in the 1962–1963 period than at any other point, including the “crisis years” of 1968 and 1971 when the Bretton-Woods system eventually collapsed.68

Eichengreen has also shown that the first dollar crisis occurred not at the end of the decade as scholars have traditionally assumed, but at the end of 1960 just as the Kennedy administration prepared to take office. Two related trends converged to undermine the dollar at that moment. First, in that year, the traded value of an ounce of gold on the open markets shot up to $40 whereas the dollar converted at $35, a moment the Kennedy’s Council of Economic Advisers later described as “the gold flutter.”69 Galbraith wrote to Kennedy in October of that year that the increase had been “unprecedented” and that the “counterpart of this is a weakening of the dollar,” which could precipitate a devaluation of the dollar.70 Second, the period of 1958–1960 was the first period since 1945 during which the United States experienced a balance of payments deficit, which would persist for the remainder of the decade, and a gold outflow of $1.7 billion in 1960 alone. As a result, 1960 was the first year where dollar claims exceeded the United States’ gold reserves. As foreign holders of US dollars, primarily Western Europeans, began to trade in their dollars for gold, fears about an eventual run on the dollar spread.

The recollections of Kennedy’s colleagues suggest that gold loss issues were not just salient across government but had a special impact on President Kennedy, who feared that by undermining the role of the US dollar as a reserve currency, gold losses posed a direct threat to US power. According to Carl Kaysen, who was the main point man on these issues in the NSC staff, “The President was occupied, and in the judgment of some of his professionally knowledgeable advisors, over-occupied with the problem of balance of payments and gold for the whole of his term in office.”71 Similarly, Paul Nitze, from the vantage point of the Defense Department, recalled that “President Kennedy … felt that this was one of the most important things that had to be controlled; that if we didn’t control this gold outflow, there could be a run on the dollar and this would be a disaster, forcing us to currency control and all kinds of things which were unattractive.”72

For many, the specter of the 1933 Banking Crisis loomed large: facing similar circumstances, the Democratic Roosevelt administration was forced to devalue amid a major financial crisis that many blamed on a lack of clear government policy.73 Kennedy’s first State of the Union address made it clear that the administration would not devalue and that it would address the deficit head on. He explained: “This Administration will not distort the value of the dollar in any fashion. And this is a commitment. Prudence and good sense do require, however, that new steps be taken to ease the payments deficit and prevent any gold crisis. Our success in world affairs has long depended in part upon foreign confidence in our ability to pay.”74

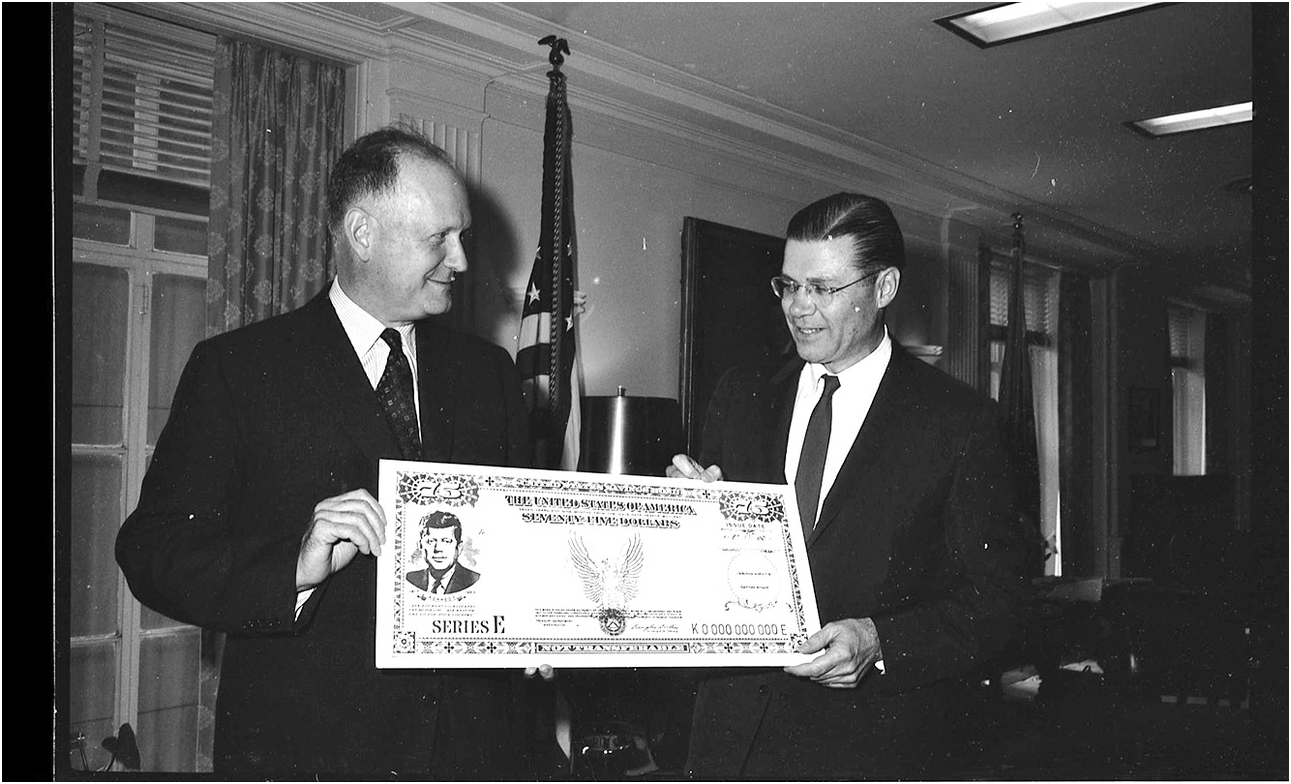

Kennedy sought to reassure key stakeholders with a message of prudence and of continuity on the economic front. Secretary Dillon’s recollections are interesting on this subject because they explain the nature of Kennedy’s concern just as they elucidate why he might have selected Republicans as Secretaries of Defense and Treasury, key posts at the intersection of foreign and economic policy. In addition to his background in finance, Dillon had served as Eisenhower’s Ambassador to France at a time when France was disengaging from Indochina and offloading the war’s costs onto its ally, the United States. In addition to his experiences in the State Department, as a member of the establishment, Dillon was a close personal friend of the Rockefeller brothers and many others in the business world, which gave him valuable access to a Democratic administration and to a young President under pressure to prove his economic credentials (see Figure 3.2).

Figure 3.2 Secretary of Defense McNamara (right) with Secretary of the Treasury C. Douglas Dillon (left), August 5, 1964. Dillon encouraged President Kennedy’s fiscal conservatism and was frustrated with President Johnson’s economic policies.

Dillon explained Kennedy’s “particular” concern over the balance of payments and the offer of the Treasury position: “He was afraid that there was a lack of confidence in the US and that nobody knew what the new policies would be. He said that I could render substantial assistance because I was known in Europe and was known to believe in the maintenance of the value of the dollar and in a sound dollar, which he very much believed in himself.”75 In and of itself, a balance of payments deficit was not a problem, and as the administration itself explained in a press release in February 1961, “early deficits in our balance of payments were, in fact, favorable in their world effect” since they had stimulated growth and thus new markets, especially in Europe.76 The danger came if dollars were converted into gold, which would threaten the stability of the dollar as the international monetary system’s reserve currency.

From the outset, the administration was alerted to “speculative fears concerning the future of the dollar”77 and especially, as Galbraith suggested to Kennedy, the risk that “Republican bankers” might seek to “embarrass the administration” by provoking a run on the dollar.78 Since devaluation was not an option for a President who had pledged to “maintain the value of the dollar,” Kennedy chose to reassure those who might initiate a speculative attack.79

As a result, Dillon became the administration’s envoy to the business community, whose confidence was needed but which was suspicious of an administration considered too liberal and intellectual for its liking. The administration had “started afoul” with business, clashing, as it had done in 1961, over steel prices and making staffing choices that accentuated fears. In the Eisenhower administration, 36 percent of appointments were from the business community; in Kennedy’s, only 6 percent were.80

Dillon reached out, among others, to his friend David Rockefeller, whose advice to the new President was that “the only way to achieve a solid solution to our balance of payments problem … is through time honored methods,” namely an expansion of exports, manipulating interest rates and, crucially, “through maintaining confidence (both here and abroad) in the soundness and integrity of the dollar.” He ended by explaining to the President that confidence could be encouraged with “more effective control of expenditures and a determined and vigorous attempt to balance the budget.”81 Rockefeller’s letter suggests that the administration’s fiscal prudence was not just an intellectual preference but also the product of real and perceived constraints, not least of which was the specter that the US business community could use underlying economic weaknesses to embarrass it.

In time, the administration acted on each of Rockefeller’s suggestions, but it could not detract from the fact that it was defense installations and not trade that drove the balance of payments deficit. In fact, trade had expanded as European economies recovered in the preceding decade and the United States ran a “very substantial, unusually large, export surplus.”82 Instead, services drove the deficit. More specifically, as a Federal Reserve report at the time concluded, over 38 percent of the deficit could be traced back to “services in connection with the maintenance of installations abroad.”83

During the presidential campaign, in a speech on the balance of payments delivered in Philadelphia in October 1960, then Senator Kennedy explained that the “first” contributor to the balance of payments was the “heavy commitments abroad for military and economic aid, and for the support of our own overseas military forces.”84 Newspapers at the time echoed his remarks and warned that “the cost of preserving American’s world-wide defense commitments, particularly the lavish establishment in Europe, has been a major cause of the outflow of gold and foreign currency, now threatening the stability of the dollar.”85

Given McNamara’s background as an economist and his focus on economical defense as well as his efforts to align defense resources and capabilities to national priorities, he turned to the issue of the balance of payments with vigor. It shaped his approach to ruthless cost cutting in all operations abroad and especially on Vietnam. In 1962, a number of factors converged to produce McNamara’s disengagement plans from South Vietnam. First and foremost, many of the economic and budgetary issues that troubled the incoming administration became especially acute just as Kennedy charged his trusted Defense Secretary to bring order to South Vietnam policy. At the same time, civilian advisors at the State Department and elsewhere produced a strategy for South Vietnam that reflected the ethos of the New Frontier and its interest in lower-level conflicts and counterinsurgency. More than that, their strategy seemed to kill two birds with one stone: it provided a possible answer to South Vietnam’s problems and a solution for McNamara’s economic and budgetary concerns.