Chronic non-communicable diseases (NCD), such as arterial hypertension and diabetes, represent one of the main causes of global morbidity and mortality, disproportionately affecting vulnerable populations in low- and middle-income countries(Reference Simões, Meira and dos Santos1,2) . Characterised by a gradual onset and prolonged evolution, these multifactorial conditions are associated with socio-economic factors, inadequate dietary patterns and limited access to health services(2,Reference Machado, Parajára and Guedes3) .

In Brazil, social inequalities amplify the effects of NCD, especially in contexts of urban poverty, such as favelas(Reference Simões, Meira and dos Santos1,Reference Rocha, Canella and Canuto4,Reference Malta, Bernal and Carvalho5) . These areas have a high population density and are home to around 16 million Brazilians, with the highest proportion of women in the Northeast region of the country(6). In addition, they suffer from social and health vulnerability, high rates of food insecurity and limited access to healthy food or its low quality(2,Reference Rocha, Canella and Canuto4,6,Reference Leite, Assis and Carmo7) .

Although the national literature points to growing trends in ultra-processed foods (UPF) consumption in the general population, there is a lack of evidence specifically linking the food environment of areas with marked inequalities, such as favelas, to NCD(Reference de Medeiros, Silva-Neto and Dos Santos8,Reference Louzada, Cruz and Silva9) . However, the combination of low income, an obesogenic food environment, and increased exposure to UPF is associated with worse health outcomes in these populations(Reference Louzada, Costa and Souza10–Reference Carvalho, Sá and Bernal12).

The focus on women in these communities is particularly relevant, as in addition to being more vulnerable to NCD(Reference Malta, Bernal and Carvalho5,Reference Carvalho, Sá and Bernal12) , they play key roles as caregivers and those primarily responsible for choosing and preparing food in the home(Reference Roy, Mazaniello-Chézol and Rueda-Martinez13). The expansion of UPF consumption, which is widely available in these environments, plays a central role in this scenario(Reference Louzada, Cruz and Silva9–Reference Srour, Fezeu and Kesse-Guyot11).

These foods, associated with aggressive marketing strategies and relatively greater affordability, have been linked to a higher risk of NCD(Reference Leite, Assis and Carmo7,Reference de Medeiros, Silva-Neto and Dos Santos8,Reference Louzada, Costa and Souza10,Reference Srour, Fezeu and Kesse-Guyot11,Reference Vitale, Costabile and Testa14) . Despite advances in food environment research in Brazil, few studies have explored how socio-economic conditions, combined with changes in global food systems, influence the dietary patterns and health outcomes of women in Brazilian favelas. These favelas are marked by a double burden of malnutrition, with simultaneous prevalence of food insecurity and obesity(Reference Rocha, Canella and Canuto4,Reference Mendes, Rocha and Botelho15) .

In view of this, this study aims to assess the relationship between the food environment in favelas and the presence of arterial hypertension and diabetes among women in situations of social vulnerability. By filling gaps in knowledge about these health determinants, it is hoped that it will contribute to the formulation of interventions that address social inequalities and health patterns in these specific contexts.

Methods

Design and study location

Cross-sectional (individual data) and partially ecological (environmental component), population-based study conducted between October 2020 and May 2021 in favelas and urban communities in the city of Maceió, capital of the state of Alagoas, Northeast Brazil.

The Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics(16) characterises favelas and urban communities as areas predominantly characterised by households with varying degrees of legal insecurity of tenure and at least one of the following criteria: absence or incomplete provision of public services; predominance of buildings, urban landscapes and infrastructure generally self-produced or guided by urban and construction parameters different from those defined by public authorities and location in areas with occupancy restrictions defined by environmental or urban legislation.

Sample size and selection

Taking into account the estimated 24 614 adult women of reproductive age (20–44 years) in the ninety-four favelas and urban communities of Maceió, along with a prevalence of 26·3 % for arterial hypertension among women aged 18 years and older in Maceió(17), adopting a margin of error of 2 % and a CI of 95 %, it would be necessary to recruit at least 1731 women. The sample size calculation was performed using the StatCalc v. 7.2.5.0 program (Center for Disease Control, Atlanta, EUA).

A total of 2356 women were invited to participate in the study, of which 1882 were included. The inclusion process is described in Figure 1. The women were recruited from forty favelas and urban communities, randomly chosen according to the criteria presented in Figure 2.

Figure 1. Flow chart for the inclusion of study participants.

Figure 2. Flow chart for selecting the favelas and urban communities included in the study.

The study used a three-stage probabilistic cluster sampling design: (i) Favelas and urban communities were selected randomly and proportionally from each of the seven administrative regions of Maceió studied. (ii) Census tracts: One was randomly selected from each favela and urban community. (iii) Streets: One street was randomly selected for data collection in each census tract evaluated.

All households on the selected street were visited, and when necessary, neighbouring ones were included until the corresponding sample size for the area was completed. All households where at least one adult woman of reproductive age (20–44 years) resided were included, with data collected from one woman per household. Pregnant women and those with any disability that compromised their food intake or prevented them from taking part in the interview or understanding the survey questionnaires were not included.

Data collection

Socio-demographic and health variables

To characterise the population, the following variables were collected: age (years), schooling (years of study) and race/skin colour (white, black, brown, yellow and indigenous). Monthly per capita family income was also assessed and classified according to the cut-off points for poverty (poverty – US$ < 91·90; and out-of-poverty US$ ≥ 91·90). Values converted from reais to US dollars, considering the average dollar exchange rate between October 2020 and May 2021 – R$5·43)(18).

Dependent variables - arterial hypertension and diabetes

The presence of arterial hypertension and diabetes was assessed through the women’s self-report of a previous medical diagnosis of these chronic conditions. To determine the presence of arterial hypertension, the following questions were asked: ‘Has any doctor ever told you that you have high blood pressure?’ and ‘Has any doctor asked you to take any medication to lower your high blood pressure?’ The second question was only asked of women who answered ‘yes’ to the first.

To determine the presence of diabetes, the following questions were asked: ‘Has a doctor ever told you that you have diabetes?’ and ‘Has a doctor ever asked you to take any medication to control diabetes?’. The second question was only asked of women who answered ‘yes’ to the first.

Those who answered ‘yes’ to the two questions relating to each disease were considered to have a diagnosis of arterial hypertension and diabetes. This method aligns with practices in other research studies(17,19) .

Independent variable - consumer’s food environment

All formal and informal retail businesses within a 400-m buffer were audited, a distance deemed suitable for assessing the relationship between the food environment and health outcomes(Reference Wilkins, Radley and Morris20). This buffer was calculated from the midpoint of the streets selected for data collection in the favela under study. A total of 624 food retail establishments were audited.

The audit was conducted using the AUDITNOVA instrument, validated for food retail businesses in Brazil, which evaluates factors such as availability, price, variety and advertising strategies in food retail(Reference Borges and Jaime21). As recommended by Borges et al.(Reference Borges and Jaime21), to characterise the food environment, the primarily marketed food group in each establishment was determined. This involved counting the number of shelves, displays and counters for each food group category (Fresh/Minimally Processed Foods; Culinary Ingredients; Processed Foods; UPF). The food group with the largest display area was considered the primary marketed group in the establishment.

From the data collected in the audit process, it was possible to calculate the healthiness score of the consumer’s food environment, composed of two dimensions: (1) food dimension (score from –27 to 56), formed by the indicators of availability and promotional price of all audited foods and beverages and (2) environmental dimension (score from –18 to 15), composed of the indicators advertising/information and placement of advertisements within the stores(Reference Borges, Gabe and Jaime22).

Finally, the values obtained in the food and environmental dimensions were summed to determine the healthfulness score, which ranges from –46 to 71 points. These scores were standardised on a scale from 0 to 100, where higher scores indicate healthier establishments. The average final score for each favela and urban community was also stratified into tertiles: the first tertile indicates low healthfulness, the second tertile indicates intermediate healthfulness and the third tertile indicates high healthfulness.

The availability of UPF for each of the audited businesses was also calculated, following the proposal of Serafim et al.(Reference Serafim, Borges and Cabral-Miranda23). For this procedure, all eighteen UPF available in AUDITNOVA were considered, and they were grouped into five subcategories: (i) sausages – sausage and pork sausage; (ii) bakery products, biscuits and snacks – bread, breakfast cereals, snacks and cookies; (iii) sweets – ice cream, chocolates and candies; (iv) sugary drinks –canned soda, 2L soda, zero/light/diet soda, nectar, mix of soda and milk drink and (v) ready-to-eat foods – ready-to-eat pizza, seasoning mix and instant noodles.

The scoring of the subcategories was constructed based on the number of available foods in each audited business: processed meats – 2 items (score 0–11); bakery products, biscuits and snacks – 4 items (score 0–22); sweets – 3 items (score 0–17); sugary beverages – 6 items (score 0–33) and ready-to-eat foods – 3 items (score 0–17). Scores were standardised on a scale from 0 to 100 points, where a higher number of UPF available in each subcategory corresponded to a higher score, as utilised in the study by Serafim et al.(Reference Serafim, Borges and Cabral-Miranda23). Consequently, the average final score for each favela was determined, which was further stratified into tertiles: the first tertile indicating low availability, the second intermediate and the third high availability.

Spatial data

The geographic coordinates (latitude and longitude) of all audited retail businesses were collected using the Google Earth v. 9.3.25.5 application (Google, United States), positioned 1 meter from their main entrance. Subsequently, this data were entered into the QGIS 3.16.15 software (Open Source Geospatial Foundation, Chicago, United States).

After this procedure, the layer containing the previously calculated buffer was overlaid with another layer containing establishment-level data to calculate average values of measures assessing the healthiness and availability of UPF. This provided information for each favela and urban community.

Data analysis

Descriptive analyses were conducted for both individual characteristics and the food environment, with continuous variables presented as mean and sd and categorical variables as absolute and relative frequencies. Variables describing the food environment were analysed continuously and presented median and interquartile ranges.

The presence of arterial hypertension and diabetes was considered as dependent variables. Independent variables included characteristics of the food environment related to healthiness (categorised values into tertiles: low healthiness, intermediate healthiness and high healthiness) and the availability of UPF (categorised values into tertiles: low availability, intermediate availability and high availability).

The association analysis was conducted using binary logistic regression through generalised estimating equations. The association was estimated by OR and their respective 95 % CI. For this procedure, three evaluation models were created: Model 1 included the healthiness of the environment, Model 2 included the availability of UPF in the environment and Model 3 included both the healthiness and availability of UPF in the environment. The models were adjusted for the following confounding variables: age (years), years of schooling, race/skin colour and poverty status. Analyses were performed using the statistical software Jamovi Computer Software (Version 2.3.28, The jamovi project, Sydney, Australia). A significance level of <5 % was adopted.

Results

The socio-demographic and health characteristics of women included in this study are available in Table 1. Regarding arterial hypertension and diabetes, 10·9 % and 3·2 % of women had these conditions, respectively. The mean age and years of formal education were found to be 31·0 years and 8·1 years, respectively. We observed that 61·1 % of the population self-identified as mixed-race (brown), and 75·8 % were living in poverty.

Table 1. Socio-demographic and health characteristics of women living in slums and urban communities in Maceió, northeast Brazil, 2020/2021 (n 1882)

* Assessed by monthly household income per capita (poverty – US$< 91·90; and out of poverty US$ ≥ 91·90. Values converted from reais to US dollars, considering the average dollar exchange rate between October 2020 and May 2021 – R$5·43)(18).

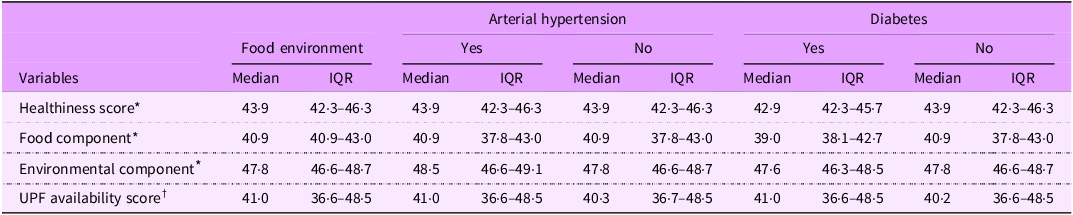

Regarding the food environment, it was identified that 31·4 % and 2·9 % of the evaluated commercial establishments primarily sold fresh/minimally processed foods and processed foods, respectively, while 65·7 % primarily sold UPF. The median healthiness score of the food environment was 43·9 (IQR 42·3–46·3) points, both in the presence and absence of arterial hypertension. Similarly, when assessing diabetes, the highest median score was observed in the absence of this NCD, 43·9 (IQR 42·3–46·3) points (Table 2). For the evaluation of UPF availability, the highest median score found was 41·0 (IQR 36·6–48·5) points, both for the presence of arterial hypertension and diabetes (Table 2).

Table 2. Characteristics of the consumer’s food environment, according to the presence of arterial hypertension and diabetes in socially vulnerable women from socially vulnerable regions of Maceió, northeast Brazil, 2020/2021 (n 624)

IQR, interquartile range; UPF, ultra-processed foods.

* Assessed according to the proposal by Borges; Gabe; Jaime(Reference Borges, Gabe and Jaime22).

† Assessed according to the proposal by Serafim et al.(Reference Serafim, Borges and Cabral-Miranda23).

Table 3 describes the association between the food environment and the presence of arterial hypertension. Through the adjusted analyses, the healthiness classified as intermediate and high of the food environment decreased the chances of women having arterial hypertension by up to 55 % (OR: 0·45; 95 % CI: 0·24, 0·81) and 62 % (OR: 0·38; 95 % CI: 0·17, 0·83), respectively (Model 1). It was also possible to observe that the availability of intermediate (OR: 1·57; 95 % CI: 1·07, 2·32) and high (OR: 1·64; 95 % CI: 1·09, 2·47) UPF in the food environment increased the odds of women having arterial hypertension by approximately 1·6 times (Model 2). When including both healthiness and availability measures of UPF in the food environment in the same model, it was identified that high healthiness decreases the odds of arterial hypertension by up to 63 % (OR: 0·37; 95 % CI: 0·16, 0·86). Meanwhile, intermediate availability (OR: 1·74; 95 % CI: 1·08, 2·85) and high availability (OR: 1·75; 95 % CI: 1·13, 2·70) of UPF increased the odds of arterial hypertension by more than 1·7 times (Model 3).

Table 3. Associations between characteristics of the food environment and the presence of arterial hypertension in women living in slums and urban communities in Maceió, northeast Brazil, 2020–2021 (n 1882)

UPF, ultra-processed foods.

The models were adjusted for age (years), years of schooling, race/skin colour and poverty status.

* Assessed according to the proposal by Borges; Gabe; Jaime(Reference Borges, Gabe and Jaime22). T1: low healthiness; T2: intermediate healthiness; T3: high healthiness of the consumer’s food environment.

† Assessed according to the proposal by Serafim et al.(Reference Serafim, Borges and Cabral-Miranda23). T1: low availability; T2: intermediate availability; T3: high availability of UPF in the consumer’s food environment.

In Table 4, it was also identified that high healthiness in the food environment decreased the odds of women having diabetes by up to 75 % (OR: 0·25; 95 % CI: 0·07, 0·97) (Model 1), while high availability of UPF in the food environment increased the odds by up to 2·2 times (OR: 2·18; 95 % CI: 1·13, 4·21) (Model 2). When both healthiness and availability measures of UPF in the food environment were included in the same model, it was observed that high healthiness reduced the odds of diabetes by up to 60 %, while intermediate and high availability of UPF increased the odds by up to 2·8 times (OR: 2·78; 95 % CI: 1·20, 6·45) and 2·2 times (OR: 2·22; 95 % CI: 1·04, 4·77), respectively (Model 3).

Table 4. Associations between characteristics of the food environment and the presence of diabetes in women living in slums and urban communities in Maceió, northeast Brazil, 2020–2021 (n 1882)

UPF, ultra-processed foods.

The models were adjusted for age (years), years of schooling, race/skin colour, and poverty status.

* Assessed according to the proposal by Borges; Gabe; Jaime(Reference Borges, Gabe and Jaime22). T1: low healthiness; T2: intermediate healthiness; T3: high healthiness of the consumer’s food environment.

† Assessed according to the proposal by Serafim et al.(Reference Serafim, Borges and Cabral-Miranda23). T1: low availability; T2: intermediate availability; T3: high availability of UPF in the consumer’s food environment.

Discussion

The findings presented in this study highlight the relationship between the food environment and arterial hypertension and diabetes among socioeconomically vulnerable populations. This relationship can potentially be replicated in other areas of Brazil, Latin America and other low- and middle-income countries around the world. An inverse association was identified between the environmental health index and arterial hypertension and diabetes, while the high availability of UPF was positively associated with these conditions in vulnerable women.

The prevalence of arterial hypertension (10·1 %) and diabetes (3·2 %) in the study is lower than the national (arterial hypertension, 29·3 %; diabetes, 11·1 %)(17) and global (arterial hypertension, 19·1 %; diabetes, 23·8 %) averages(Reference Ochmann, von Polenz and Marcus24), indicating the importance of considering this vulnerable context in the future perspective of health investments(Reference Saldiva and Veras25). From this increase, especially in more vulnerable areas, it is possible to detect NCD, such as arterial hypertension and diabetes, at an early stage(Reference Figueiredo, Ceccon and Figueiredo26). However, there are significant barriers to the prevention and adequate treatment of NCD in Brazil, including low health coverage, an insufficient number of health professionals, and the need for more priority to promote an adequate and healthy diet(Reference de Oliveira, Duarte and Pavão27,Reference Bortolini, de Oliveira and da Silva28) .

Therefore, actions related to chronic diseases must take into account the influence that the food environment has on food choices and health outcomes, which are affected by factors such as availability, variety, price, quality, advertising and marketing strategies and household access to food(Reference Borges and Jaime21,Reference Serafim, Borges and Cabral-Miranda23) , as well as socioeconomic, cultural, territorial, biological and individual conditions(Reference Rocha, Canella and Canuto4,Reference Meijer, Nuns and Lakerveld29) .

The food environment in economically vulnerable areas lacks commercial establishments that offer healthy, quality food options, as identified in this study, in which the majority of the establishments evaluated sold mainly UPF(Reference Rocha, Canella and Canuto4,Reference Mendes, Rocha and Botelho15) . As a result, economically vulnerable populations increasingly have access to cheaper food of lower nutritional quality, which leads to the adoption of inadequate eating habits(Reference Menezes, Oliveira and Almendra30) and is related to the current epidemiological profile of the population(Reference Meijer, Nuns and Lakerveld29).

Our results show that the greater availability of UPF in the food environment is positively associated with the presence of arterial hypertension and diabetes. Worryingly, there is widespread marketing, distribution and consumption of UPF with high sugar, Na and saturated fat content, high-calorie concentration, high glycaemic index and low fibre content in Brasik(Reference de Medeiros, Silva-Neto and Dos Santos8,Reference Louzada, Cruz and Silva9) .

These associations highlight the need for interventions that promote healthy food choices and reduce the presence of foods known to be harmful to health, such as UPF(Reference Nguyen, Cranney and Bellew31). Therefore, at the heart of addressing the food environment in the context of NCD is the urgent need to transform the dominant food system and, consequently, the food environment. This transformation involves strengthening local food production and increasing the availability of and access to healthy foods that are part of regional food cultures, thus helping to reduce dependence on UPF and protect the health of the population(Reference Madlala, Hill and Kunneke32,Reference Popkin, Barquera and Corvalan33) .

Our results corroborate the observations of studies that have evaluated the influence of the food environment on eating behaviour, directly impacting the occurrence of NCD(Reference Oliveira, Menezes and Almendra34), especially CVD(Reference Meijer, Nuns and Lakerveld29). In fact, the characteristics of the food environment can influence a population’s eating patterns in various ways(Reference Rocha, Canella and Canuto4), particularly in the consumer’s food environment, where the availability, easy access and predominant presence of UPF can lead people to consume these foods more frequently, adopting unhealthy eating patterns(Reference Menezes, Oliveira and Almendra30).

In addition, the characteristics of UPF affect the development and worsening of diseases in a continuous and chronic process since prolonged consumption of these foods leads to adaptations in eating behaviour that prevent individuals from stopping or reducing their intake(Reference Silva-Neto, da Silva Júnior and Bueno35). Energy intake from these foods, especially among socially vulnerable women, is increasing(Reference de Medeiros, Silva-Neto and Dos Santos8), which leads to an increase in body adiposity, especially visceral fat deposition, which tends to trigger pro-inflammatory processes through the release of substances such as adipokines, which raise blood pressure and negatively influence insulin action(Reference Zorena, Jachimowicz-Duda and Ślęzak36).

Additional mechanisms related to UPF deserve attention. Chemical additives not used in traditional food preparation (emulsifiers, non-nutritive artificial sweeteners and thickeners) are added to these products, with already recognised negative cardiometabolic effects(Reference Monteiro, Cannon and Levy37). In addition, UPF are hyperpalatable, relatively cheap, practical and widely available, which favors high consumption in the general population(Reference Monteiro, Moubarac and Levy38). In this context, broadening the focus to NCD and the environment in which people live makes it possible to identify the challenges to better address these conditions. Thus, the results of this study are useful for supporting the adoption of public policies that enable people to adopt adequate and sustainable dietary practices.

In contrast, our findings also highlight that a healthier food environment, with a greater presence of fresh and minimally processed foods, showed a negative association with the presence of arterial hypertension and diabetes. Being in a healthier food environment reflects positively on diet quality(Reference Vinyard, Zimmer and Herrick39), helping to prevent non-communicable chronic diseases(Reference Bevel, Tsai and Parham40).

This is because physical and financial access to fresh food can encourage healthy food choices, positively influencing eating habits, especially among socioeconomically vulnerable populations(Reference Madlala, Hill and Kunneke32). We also emphasise that dietary recommendations for the prevention and control of NCD are difficult to adopt and maintain in an environment that promotes and encourages habits and attitudes contrary to these practices(Reference An and Chen41).

In this context, public policies should aim to facilitate the adoption of healthy and sustainable practices(Reference Skeggs and McHugh42), incorporating environmental and lifestyle factors, such as taxing UPF(Reference Valizadeh and Ng43), subsidies for the production of fresh/minimally processed foods(Reference Popkin, Barquera and Corvalan33) and front-of-pack labeling, which helps consumers with clear information about the composition of foods(Reference Ganderats-Fuentes and Morgan44). In addition, it is essential to regulate marketing strategies used to promote UPF and implement permanent policies, such as school feeding programs, encouraging healthy habits from an early age. However, changing the food environment through regulatory measures faces challenges, such as a lack of political support, food industry strategies, financial limitations and the population’s resistance to accepting these changes(Reference Nguyen, Cranney and Bellew31). In this sense, food education has emerged as a crucial tool for raising public awareness of the importance of gradually transforming the food environment, reducing the consumption of UPF and promoting healthier choices.

At the same time, it is necessary to expand initiatives that guarantee fair access to healthy food, considering the financial and structural barriers faced by vulnerable populations(Reference Valizadeh and Ng43). The FAO High-Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition emphasises that inadequate food environments compromise food security, especially in vulnerable urban populations, contributing to the double burden of malnutrition and increased NCD(45). Key recommendations include strengthening access to fresh and healthy food, encouraging local production and distribution, regulating marketing practices that promote UPF and developing integrated policies that address structural inequalities in food supply(45).

Our study has strengths and limitations. Our strengths include the novel association found between consumer food environment characteristics and two NCD among women living in favelas in a Brazilian capital. In addition, our study assessed the food environment through audits in commercial establishments using an instrument validated for the Brazilian context, which is an effective method for assessing the quality of the food environment. This approach provided a systematic, standardised and comprehensive assessment(Reference Lytle and Sokol46).

As limitations, we can point to the self-reported medical diagnoses of arterial hypertension and diabetes by the participants, especially considering their low level of education. For this reason, results can be underreported. Some women may have arterial hypertension or diabetes and have not yet been diagnosed. However, as mentioned above, this method is used by the Brazilian government to assess the prevalence of these two diseases in the country. This form of assessment has been used in Brazil for many years, with the entire population, regardless of their education or economic situation. In addition, our sample is made up of women living in poverty, which can limit access to healthcare and medical diagnosis of these conditions. These factors may have influenced the relatively low prevalence of diabetes in our sample.

However, a study evaluating individuals with a medical diagnosis of diabetes found that 75 % of them accurately reported their diagnosis(Reference Shah and Manuel47). Self-reported arterial hypertension, on the other hand, has high specificity (88 %) and moderate sensitivity (77 %) in Brazilian studies, demonstrating its validity as a population screening tool, especially in homogeneous contexts, such as vulnerable communities, where access to formal diagnoses is limited(Reference Moreira, Almeida and Luiz48). Studies also point to greater congruence in reports among women, possibly due to the central role they play in family health care, which reinforces the method’s reliability in female populations. Thus, self-reported arterial hypertension is a valid strategy for identifying health trends in groups with specific socioeconomic and cultural characteristics, such as women in slums(Reference Moreira, Almeida and Luiz48,Reference Bonsang, Caroli and Garrouste49) .

In addition, the associations found between food environment variables and the health conditions analysed should be interpreted with caution. Cross-sectional studies’ limitations include possible confounding factors and different time intervals between exposure and results. Therefore, although the study allows for the generation of new hypotheses and contributes to a comprehensive analysis in conjunction with other available scientific evidence, it reduces its ability to establish causality. We recommend conducting prospective studies to further explore the causality between the characteristics of the food environment and the health outcomes assessed.

In conclusion, our results suggest that the characteristics of the consumer’s food environment (lower healthiness index and high availability of UPF) significantly influence the prevalence of arterial hypertension and diabetes, especially among socially vulnerable women. Improving the food environment, with lower availability of UPF and greater access to healthy foods, is an intersectoral strategy that can contribute significantly to preventing and reducing the prevalence of arterial hypertension and diabetes in vulnerable women.

Acknowledgements

To all the women who participated in this study. To the research team who worked hard to make this study possible. To the Nutritional Recovery and Education Center (Centro de Recuperação e Educação Nutricional - CREN) of Alagoas for all logistical support.

Authorship

L.G.R.S.-N. and T.M.d.M.T.F.: contributed to data collection, the conception and design of the study, statistical analysis, interpretation of results and writing of the manuscript. R.C.E.d.M., J.S.O. and N.P.d.S.: contributed to data interpretation, manuscript writing and critical revision of the intellectual content. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the work.

Financial support

Luiz Gonzaga Ribeiro Silva-Neto was supported by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior–Brazil (CAPES) research fellowships (grant number: 88887.081866/2024-00).

Competing interests

There are no conflict of interest.

Ethics of human subject participation

This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Alagoas (approval number: 4,836,765). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.