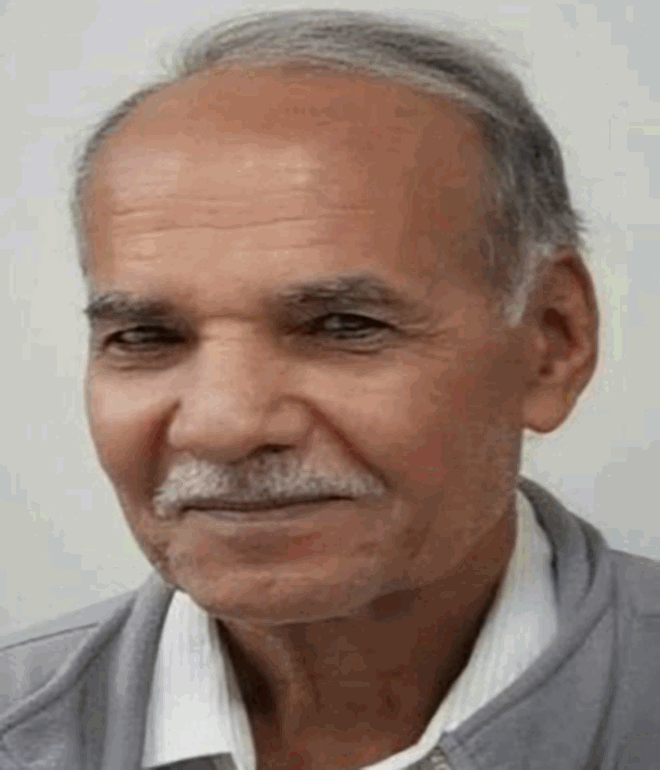

The world of Islamic art has suffered a calamitous loss with the sudden death in Tehran, from Covid-19, of Abdullah Ghouchani on 7 August 2020. He was a truly towering figure, the greatest epigrapher in the world in medieval Arabic and Persian, with a near-miraculous capacity to read the unreadable. He did his work without fanfare and he generously made his knowledge available to those who sought his help. For him, information was to be shared, not hoarded. He loved to share his discoveries. As a result, he was in high demand, especially among his museum and university colleagues, not just in Iran but globally, for over forty years. He published widely, but a huge amount of the work that he did, though it will be preserved in the records of museums and institutions of learning, will see publication only gradually in the decades to come, and not under his name, though one hopes that his key contributions will be acknowledged. But in any case, he was not greedy for glory. Indeed, one of the wise sayings that he deciphered on Samanid pottery fits him like a glove: “generosity is a quality of the people of Paradise” (al-judu min akhlaqi ahli’l-janna).

Abdullah Ghouchani was born on 11 August 1948 in Baghdad, of Iranian parents. He spoke Persian at home but it seems that his Arabic was better, and indeed that his Persian had an Iraqi accent. He completed his primary, secondary, high school and university education there, taking a BA in Arabic Language and Islamic Law at the University of Baghdad in 1971. With the rise to power of the Ba‘th party and Saddam Hussein, Abdullah’s family (being of Iranian origin) was forced to leave Iraq (in the first wave of the mass deportation of Iranians in 1972). So Abdullah made his way to Iran —for the first time in his life—and settled there, easing his passage into a Persian-speaking environment by watching plenty of Persian films. He first found work, after his mandatory military service, as a teacher of Arabic for six months in 1974 in Turbat-i Jam, Khurasan. The fact that his native language was Arabic—he himself stated that his first languages were Arabic and Persian—and that he was entirely at home in Arabic culture and literature proved to be a priceless asset for his later work as an epigrapher. This training gave him the kind of background that western scholars of Islamic studies simply cannot match. So he was formidably equipped for the tasks he undertook—bilingual in written and spoken Arabic and Persian, and with a quasi-magical touch in deciphering the most difficult inscriptions. He had the necessary context for epigraphy at his fingertips, and his interests and expertise extended far beyond the Iranian sphere.

He started his career in the Iranian Centre for Archaeological Research in 1975 and continued it in the National Museum of Iran. While working there he pursued his Master’s degree, eventually gaining an MA (in Islamic history) at Tehran. He retired from the Iranian Research Institute for Cultural Heritage and Tourism in 2004. This career path permitted him to work on occasion at the University of Tehran (where he taught at Master’s level for ten years, even before he obtained his own MA), the Tehran branch of the Āzād University (three years), the Muqaddas Ardabili University in Ardabil (one year) and the Mirath-i Farhangi Institute in Tehran (three years). In Tehran he was active in the Golestan Museum and the Reza Abbasi Museum, and he also worked in many local museums throughout Iran. Moreover, he acted as advisor to several PhD students, and in recent years held a number of workshops in Iran. Between 1988 and 2004 he also took up various international fellowships in Berlin (at the Deutsches Archaeologisches Institut), London (the British Museum), Oxford (the Ashmolean Museum), New York, Los Angeles (at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art), Washington, Toronto (at the Royal Ontario Museum) and Paris (at the Louvre). He remained a loyal member of the Iranian Centre for Archaeological Research and the future Cultural Heritage Organization of Iran even after his official retirement in 2004.

How did his interest in epigraphy emerge? Here it is best to quote his own words:

Soon after I started my career with the Iranian Centre for Archaeological Research, when its director realized that my first language was Arabic, he suggested to me that I should work on inscriptions. In the beginning, due to my lack of any experience with inscriptions, reading Kufic was difficult for me; however, after 6 months I was able easily to read Kufic inscriptions. My first serious experience was to read the inscriptions of Nishapur, including 140 earthenware dishes, which led to my publishing 2 books in Persian and English in 1985 and 1986. After that, I started to read square Kufic inscriptions, so I chose four famous monuments in the city of Isfahan and this led to my publishing the book on square Kufic inscriptions.

It is salutary to note that his first big assignment was to tackle the inscriptions of Samanid pottery, many of which had for decades defeated the best epigraphers because of their legendary difficulty. Thereafter, he never looked back. The world of scholarship may indeed be grateful to the foresight of that energetic and charismatic director of the Iranian Centre of Archaeological Research, Dr. Firouz Bagherzadeh, for recognizing and nurturing Abdullah’s talent. And over the years that talent was respected and esteemed by his colleagues in Iran. He was buried in a special part of the Behesht-i Zahra Cemetery dedicated to Iranian artists (honarmandan), which shows how highly he was highly regarded in Iran.

His largely post-retirement career at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, which houses the most extensive collection of Islamic art in the United States, was the jewel in the crown of the last years of his life. In fact his association with this museum began in 1997. Before his arrival, the Department of Islamic Art had relied on Annemarie Schimmel (d. 2003) as its informal epigrapher, and she had done sterling service for many years, especially in calligraphy. Abdullah’s range was substantially wider and he was able to spend much more time in the department. He simply devoured work, and methodically made his way through a substantial part of the collection.

This second career, involving yet another move to a foreign country, required determination, self-belief and vision. He possessed these qualities in full measure; one colleague wrote of him: “I will never forget those blazing eyes and the fierce pride that surrounded him like an aura.” He quickly saw that he would need a Green Card, so he went about his application in a very deliberate way, hiring a lawyer who pushed hard for him and was able to secure that much-coveted document on his behalf. With that in hand, he was able to bring his two daughters to the US, and they enrolled in the City University of New York, where both studied computer engineering and went on, to his immense pride, to land good jobs in that general field. Indeed, when Golnaz graduated and got a job on the east coast, Abdullah joyfully announced this success to his colleagues at work. He well understood how important it was for his daughters to be in a place where they could succeed on their own merits—and they did. As for himself, he entered on this second career, in a culture, land and language not his own, with energy and steadfast commitment. As another colleague said of him, “he had moxie and wasn’t afraid of advocating for himself.” Happily he had a brother in California, whose help he acknowledged in his book on Samanid pottery.

At the Met he was on a succession of contracts with such titles as Research Associate and Senior Fellow. He began (1997–98) by reading the inscriptions on all the museum’s Saljuq and Ilkhanid ceramics and tiles. In 2008–09 he worked on the museum’s gallery reinstallation project. In this period he was also able to read and transcribe the Persian and Arabic inscriptions on the works included in the Masterpieces from the Department of Islamic Art catalogue (2011) and on the objects flagged for the 2011 galleries. These alone are superlative achievements. But his contribution went far beyond these three specific tasks, for between 2005 and 2020 he was the resident epigrapher, mentor and scholarly guide to the Islamic department, consulting for the galleries in 2008–11, and contributing to the Deccan symposium Sultans of the South (2008), with a piece on the inscriptions of the Ibrahim Rauza shrine in Bijapur. He also contributed to the volume accompanying the Deccan exhibition, Opulence and Fantasy: Sultans of Deccan India (2015) and to the exhibition Court and Cosmos. The Great Age of the Seljuqs (2015–16) and its catalogue, reading the inscriptions on many scores of objects. He wrote a theme page for the Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History on the rare coins excavated at Nishapur in the Museum’s collection (c. 2017–20). He worked primarily as an epigrapher and on classical texts, especially poetry and history. He was very talented in using the databases of Persian poetry and it was particularly impressive that, as one colleague recalls, he found verses on pottery that had previously been thought to be the work of well-known poets—but those poets lived after the pots were made! That makes one think about what was, so to speak, floating in the air and how a humble object with an inscription can yield a glimpse into the rich world of medieval Iran. Abdullah also helped to build the museum’s library of electronic literary sources. All was grist to his mill; the range and depth of his knowledge was awe-inspiring. He could handle the inscriptions and the verses in the Persian and Mughal albums; he recorded poetic inscriptions for the Met’s website; and he updated inscriptions for the Met’s database of objects. All in all, he was an indispensable member of the department’s team.

But there was so much more to him than that. His colleagues recollect with affection how keenly he was interested in people, projects and activities in the department and how he made himself part of them in his own discreet way. He was a keen observer of events and often expressed wry insights into what was going on. They remember that he was always impatient to share his ideas, insights and discoveries, striding into their offices with enthusiastic insistence. They recognized him as a workaholic of sorts who relished every challenging inscription that came his way. They were happy to spend hours and hours in his company, going over materials and discussing objects, and they miss him very much. He kept them connected to Iran, and the museum community there, in many formal but also informal ways. For many years he was the go-to person for those who wanted help with inscriptions and texts: not just curators and researchers in the Department of Islamic Art, but countless Fellows and interns. He was always willing to read inscriptions for colleagues in other departments such as Arms and Armor and Textile Conservation, as well as for scholars of Islamic art outside the Met. He also worked on projects involving epigraphy for the Louvre, Hermitage, the British Museum, the Brooklyn Museum, Newark Museum, Purdue University and many more museums, institutions and collections in several countries, gradually producing a truly formidable body of work. This, then, truly was a man who made a difference.

The roll-call of his current projects, left unfinished at his death, makes the head spin. At the Met alone he was working on two projects with Navina Haidar. In the Speaking Object project he was collaborating with a group in Iran to transcribe, translate and read out the inscriptions on objects in a special digital program. In the Jahangir project he was examining the material in Iranian collections, including the Golshan album, in preparation for a future Jahangir exhibition. In the Fuqqa’ project with Martina Rugiadi he was analyzing a poem about two vessels. This ironic piece highlighted and supported his earlier interpretation of fuqqa’ (the spheroconical vessels which had triggered so much controversy) as containers for beer. His publication of this theory in the prime journal of the field, Muqarnas (IX, 1992, 72–92, with Chahriyar Adle), was a triumph, decisively overturning the theories proposed by some of the great names among scholars of Islamic art. His last major project at the Met, in collaboration with Maryam Ekhtiar, was devoted to the coins of Nishapur—to identify them, read and prepare a preliminary translation of their inscriptions, and catalogue them. This project, which is ongoing, embraced all the coins (more than 600) from the Museum’s extensive excavations at Nishapur in the 1930s. This work is available as he left it on the Met’s website. He had arranged with the conservators to have the coins cleaned, but a larger and more ambitious catalogue was not in the works because the grant money had run out. Ideally, the Metropolitan Museum would have joined the Iran Bāstān Museum in a co-publication of all the excavated Nishapur coins. But the basic spade-work has been accomplished. And his formidable capacities as a numismatist in this particular area can be appreciated in his publication of the Rayy hoard of Nishapur coins: Ganjina-yi sikkaha-yi Nishabur makshufa dar shahr-i Rayy (Tehran, 1383/2004; 448 pages). He established connections with numerous other numismatists, not just in the New York area but worldwide, and coins were a topic of perennially absorbing interest for him.

What of his publications? In the nature of things, few of his readings could be published separately, since they became part of the permanent museum record for each of the objects whose inscription(s) he had read. But he did publish his decipherments and interpretations of key pieces, such as an inscribed Mongol paiza, the famous Freer luster plate, or a seal bearing the astonishingly early date of 22 AH. And he wrote many more articles of this kind.

His most important books are, in chronological order:

Angular Kufic on Old Mosques of Isfahan (Khatt-i Kufi mu‘aqali dar masajid-i bastani-yi Isfahan) (Tehran,1364/1985, 199 + 16 pages).

Inscriptions on Nishabur Pottery (Katibaha-yi sufal-i Nishabur) (Tehran, 1364/1986; 301 + 16 pages).

Rey Hoard of Nishabur Dinars (Ganjina-yi sikkaha-yi Nishabur makshufa dar shahr-i Rayy) (Tehran, 1383/2004; 448 pages).

Persian Poetry on the Tiles of Takht-i Sulayman (Ish‘ari-yi farsi-yi kashiha-yi Takht-i Sulayman) (Tehran, 1371/1992, 121 pages + 24 pages of plates in color).

Ahadith-i kashiha-yi zarinfam-i Harami mutahhar-i Imam Rida (Hadiths on Luster Tiles of the Shrine of Imam Rida) (Tehran, 2019; 426 pages).

To these should be added the following short books:

Masjid i Jami‘-yi Sava (Jame‘ (Congregational) Mosque of Saveh) (with Abolfazl Farahani) (Tehran, 1380/2001; 104 + 7 pages).

Gunbad-i Sultaniya ba istinad-i katibaha (Tehran, 1380/2001; 104 pages).

Katibaha-yi Masjid-i Jami‘ va Imamzada-yi ‘Abdallah, Shushtar (Inscriptions of Shushtar Great Mosque and Shrine of Imamzadeh Abdullah (Tehran, 1382/2003; 57 pages).

Barrasi katibaha-yi Masjid-i Jami‘-yi Gulpaygan (Inscription of the Golpaygan Great Mosque) (Tehran, 1382/2003; 65 pages).

Barrasi-yi katibaha-yi binaha-yi Yazd (Research on Inscriptions of Yazd. Architectural Structures of Yazd) (Tehran, 1383/2004).

His last book on the luster tiles in the Mashhad shrine was one in which he took particular pleasure, though the process of publication was slow and Abdullah noted that the publisher had altered the cover (he did not specify how). This huge volume (426 pages) will assuredly be a landmark in the study of medieval Iranian luster tiles, not least for the information it yields on the career of perhaps the foremost potter of pre-Mongol Iran, Abu Zayd. As examples of how he participated in multi-author volumes, apart from those cited earlier, one might mention Jahrbuch des Museums für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg. Neue Folge: 1998–2000 (Hamburg, 2002), and An Anthology from the Islamic Period Art (Tehran, 1996); the work on the inscriptions in this latter book is all his. A listing of his articles, which is not up to date and therefore only partial, can be found at: https://independent.academia.edu/AGhouchani

To strike a personal note, I am proud to say that I was his colleague and worked with him on various projects, especially on a forthcoming book on the vanished Saljuq mosque of Van. To me he was a beacon of Iranian culture. His range was extraordinary, extending from architecture to the manufacture of luster tiles to coins, manuscripts, metalwork and textiles—and his writing was informed by his profound knowledge of Islamic history and of both Arabic and Persian literature. I had a huge respect for him, and already I miss him sorely. But he was so much more than an epigrapher of genius. I really liked and admired him as a human being, and was most impressed by the way he carved out a life for himself in the very different society of America. That took courage. He was a kind and gentle man, with a shy smile and a distinctive quiet charm that was all his own. He wore his learning lightly. He was quite remarkably modest, though he well knew his own worth. He loved what he did, and this made conversations with him delightful. I treasure the memory of those encounters. In my opinion he did not receive all the honors that his achievements deserved; I said this to him on one occasion, but he just waved it all away. That was a very telling and truthful gesture: it revealed the measure of the man. He was a model scholar and a moral man. He has gone before his time; he was indeed a nonpareil and we shall not see his like again.