On 6 December 1937, Shanghai's newspaper the Chinese Press reported that a Red Cross Drive concert to be held two days later was going to be ‘the best extravagant treat planned for the music lovers of the city's cosmopolitan community’ and that ‘the benefit performance will bring together several of Shanghai's famed artists’.Footnote 1 According to this article, the concert would start with the city's Municipal Orchestra playing Avshalomov's ballet The Soul of the Chin, followed by two Chinese pieces, the pipa solo Downfall of Chu and the ensemble piece Moonlight of Chingyang by members of the Shao-Chao Institute. The second half would start with the Municipal Orchestra playing Schubert's Marche Militaire, followed by Lois Woo's performance of the first movement of Edward Grieg's Piano Concerto and two vocal numbers by the famed soprano Mary Waung. The concert would conclude with Brahms's Hungarian Rhapsody No. 1 by the Municipal Orchestra.Footnote 2

I draw attention to this ‘Red Cross Drive’ concert as an example of the intersection of colonialism, cosmopolitanism, nationalism, and musical life in interwar Shanghai. Concerts like this, I argue, were performative utterances of not only colonialism but also cosmopolitanism: they brought together Western and Chinese music and musicians of different origins even though relationships between people and music were mediated by colonial hierarchy. They also laid the foundation for the trajectory of Western music in China at a time when aspects of Western culture were considered vehicles for nation building. These concerts were the originary site of Western art music in contemporary China, a scene which is so vibrant today that it is thought to be holding the key to the future of Western music.Footnote 3 The case of Western music in interwar Shanghai allows us to ponder questions such as the following: what roles did music play in an inter-racial society such as interwar Shanghai? What was responsible for the transculturation of China's musical soundscape and who were the actors in the transculturation process?

This article stems from a prior projectFootnote 4 that tracked the concert programmes of the Municipal Orchestra in Shanghai (SMO). An icon of colonial power, the SMO was the first professional orchestra in China once hailed ‘Far East No. 1’.Footnote 5 Within these programmes, most of them written in English, I noticed an emerging trend of Chinese musicians’ participation after 1929.Footnote 6 Further research into these musicians’ backgrounds revealed their particular connection to the National Conservatory of Music founded in Shanghai in 1927.Footnote 7 Placing the SMO's programming trend in the historical context of socio-political changes in interwar Shanghai and triangulating the identified concerts and musicians with archival sources, programme notes, newspaper clippings, concert reviews, and musicians’ memoirs, I attempt to unravel the meanings of Western music concerts in Shanghai. In this endeavour I also draw on the notion of ‘performative’, a concept borrowed from performance studies.

In music scholarship, despite the rising interests in music performance, music's performativity as a concept is, however, not adequately examined. Or, to put it differently, it has been approached independent of its original meaning.Footnote 8 The term ‘performative’ came from the phrase ‘performative utterance’, which was first used by the philosopher John Langshaw Austin to refer to words, expressions, and statements that could be ‘operative’ and ‘doing something’ so as to ‘bring a state of affairs into existence by being uttered’.Footnote 9 Judith Butler then used the term to explain gender identity.Footnote 10 Seeing our daily acts as performed, she defined gender as ‘a stylized repetition of acts’ and ‘a constructed identity, a performative accomplishment which the mundane social audience, including the actors themselves, come to believe and to perform in the mode of belief’.Footnote 11 In other words, many of the things we do in conjunction with our identity, such as what we wear and how we behave, let others know who we are just as certain verbal utterances do. Music is a form of identity utterance too, which has been examined in an array of studies.Footnote 12 Music performance, due to its visuality, adds credulity to the utterance. It is thus seen to play a role in identification as it gives community members an opportunity to see themselves in action while at the same time imagine others sharing the same style of music.Footnote 13 The affective process of music performance also encourages its participants (both performers and spectators) to refigure who they are, redefining the self and its relationship to the community that he/she belongs to. Performance, according to William Beeman, is a purposeful enactment or displayed behaviour carried out in front of an audience that takes place within culturally defined cognitive frames with identifiable boundaries that can also serve as a safe and protected frame for the participants to practise their emotions. Though what Beeman observed may not be the objective of all performances that are iterative, ongoing, and ultimately unpredictable by nature, a performance generally aims towards changing the cognitive state of its participants.Footnote 14

The performance of Western music, I suggest, is a performative utterance that enacts a range of intentions and motivations, implicit or explicit, which do have impact on its participants. Building on the usage of the performative as an act to project meanings and also to trigger actions and changes, I explore how Western music concerts in Shanghai were deployed by different communities as a form of identity negotiation beyond its default association with Westerners. This move allows me to extend the understanding and application of the ‘performative’ concept beyond current music scholarship's use of the term to refer to music performance only and to articulate Western music performance in Shanghai as the performative of three outwardly contradictory ideologies – colonialism, cosmopolitanism, and nationalism – that were intersected and intertwined.

In this article, I will first analyse the performative aspects of Western music in colonial Shanghai by discussing the various activities of the Municipal Orchestra, an iconic institution of this rapidly changing city. Second, I will examine another important institution in Shanghai's Western music scene, the National Conservatory founded in Shanghai in 1927. This section provides a glimpse into a Chinese institution that aspired to train Chinese musicians in Western music. The following section documents the emerging collaboration between the Municipal Orchestra and the National Conservatory and shows how the collaborative concerts became a site in which different groups in Shanghai could project and negotiate colonial, cosmopolitan, and national ideals. Last, I will unravel the performative complexities of concert life in 1930s Shanghai through a detailed analysis of the ‘Red Cross’ concert mentioned at the beginning of this study.

Western Music and Shanghai

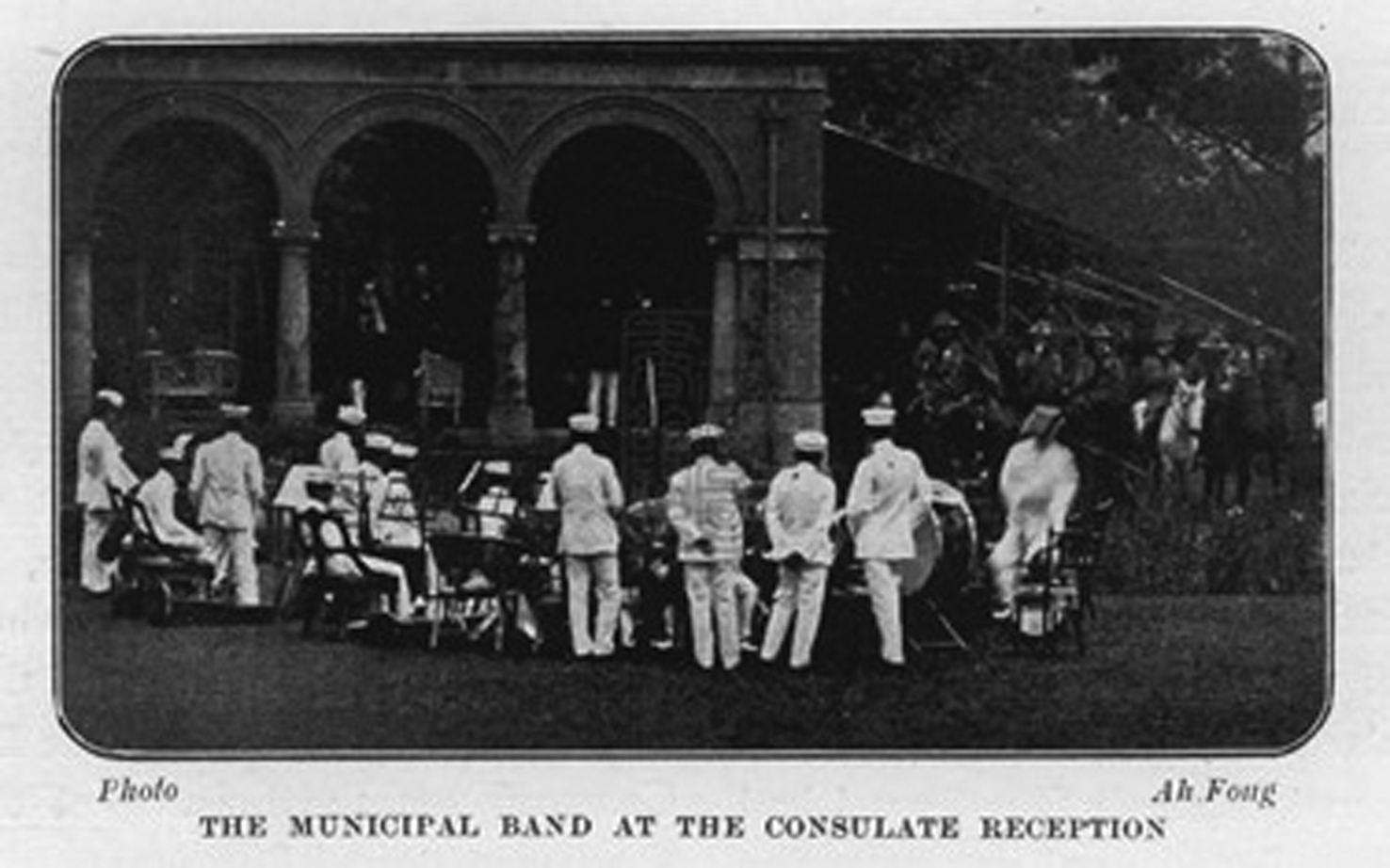

Western music in the early twentieth century and interwar Shanghai was first and foremost a performative utterance of colonialism and settler colonial identity, a phenomenon also found in other colonial cities and settler communities such as Tianjin in China, Hanoi in Vietnam, and Manila in the Philippines. Shanghai, which literally means ‘upon the sea’, was one of the five Chinese treaty ports opened to foreign trade and settlement following the 1842 Treaty of Nanjing, signed in the wake of Qing China's defeat by the United Kingdom in the First Opium War. Interwar Shanghai was a multi-racial society ruled by three jurisdictions: International Settlement and the French Settlement, where foreign subjects enjoyed extraterritorial rights, and the Chinese Settlement. Western music in the settlements displayed Western lifestyle, cultural identity, and most of all, sovereign power that explicitly distinguished Western settlers from Chinese residents. The founding of the Public Band, predecessor of the SMO in 1879, is a case in point (Figure 1).Footnote 15 The band supporters’ middle-class aspiration and reverence for European culture – their ‘home’ culture – was best illustrated in the Municipal Council members’ argument for the band to be converted to an orchestra in 1906.Footnote 16 It was thought that since high arts such as theatre, opera, and museums were not available in Shanghai, they should at least have good music by revamping the existing public band into a full orchestra.Footnote 17 Motivated by such a colonial and middlebrow desire, the municipal band was turned into an orchestra in 1907, although its name change to the Municipal Orchestra and Band took place only in 1922.Footnote 18

Figure 1 The Municipal Band, c. 1906.

The SMO's summer concerts at the public parks’ bandstands were iconic of the city's colonial context. These public concerts displayed Western sovereignty and racial divide, in addition to providing entertainment to settlers. Before 1928, Chinese residents in the settlements, aside from amahs who accompanied their employer's Western children, were not allowed to enter the parks. In fact, the Municipal Council's construction of public parks in the early twentieth century was motivated by complex agendas, as pointed out by the historian Dorothée Rihal. Some of the public parks bore bigger political agendas than merely providing leisure space for the European settlers in Shanghai. For instance, both the Hongkew Park (1909) and Jessfield Park (1914) were built on purchased lands in the Chinese territory as a part of the settlement's expansion plan to further assert its power, influence, and presence. Evidently, the park concerts carried multiple meanings: they performed British sovereignty and empire, showcased settlement lifestyle, provided relaxation and entertainment, and upheld the settler community's value of ‘good music’ (Figure 2).Footnote 19

Figure 2 (Colour online) Bandstand in the public garden.

Western settlers in Shanghai were vocal about their city's musical institution and had high expectations for the outdoor concerts. For example, a reviewer from 1920 complained that the concert programme was not classical enough and that the Public Garden, the oldest park in the settlement, was surrounded by noise.Footnote 20 Even though the two long-reigning directors of the SMO – Rudolf Buck from Germany (1907–17) and Mario Paci from Italy (1919–42) – were first reluctant to conduct such outdoor concerts, Paci succeeded in transforming them into the city's prestigious events. For example, by a number of accounts, the first open-air concert at Hongkew Park in summer 1922 was a great success that showcased the Peer Gynt Suite, extracts from Madam Butterfly, and Schubert's ‘Unfinished’ Symphony. The audience was able to hear the music even from a distance as the concert used amplification. A concert reviewer even suggested that the success in attendance ‘was a direct contradiction to the frequent assertion that the Shanghai public is not a music loving one’.Footnote 21

As mentioned in the Municipal Council Report, the 1922 summer season of the SMO was extremely successful. The first concert attracted 1,800 people, and by the fourth concert there were approximately 3,500 people in the audience.Footnote 22 The same format thus continued in the following year and after. The Municipal Council even installed a new bandstand with a shell-shaped sounding board at the Jessfield Park. The first concert at this park in June 1923 was reported to have attracted a large audience, and because of the new device, ‘there was no difficulty in hearing anywhere, although the seats stretched back for a long distance from the stand’.Footnote 23

But let us not forget that in 1923, the preceding concerts had no Chinese attendees due to the discriminatory practice of the Municipal Council. As Chinese were not allowed to be inside the city's Town Hall before 1925 or the public parks before 1928,Footnote 24 they were barred from all the SMO concerts. These concerts therefore reiterated colonial policies responsible for the racial divide and hierarchy. Nonetheless, Shanghai's Western music scene changed considerably after the mid-1920s due to the Chinese public's changed attitude towards Western influences after the New Culture Movement (1919) as well as the changes in the Settlements’ policies mentioned previously. Western music was no longer the exclusive cultural domain of settlers from the West. Chinese musicians were able to take part in musical activities not only in their own community but also the Western community, which will be discussed in a later part of this study.

A National Conservatory of Western Music

It was in the colonial context discussed previously that the Guoli Yinyue Xueyuan (the National Conservatory of Music), the first music conservatory in China, was founded in Shanghai in 1927. The founding of such an institution performed three intertwined ideals: colonialism, nationalism, and cosmopolitanism. It is not surprising that a conservatory negotiated ideals that appear to be contradictory at first glance. After all, a conservatory is not merely a place where Western music teaching and learning take place; it is viewed as a metaphor of the larger society,Footnote 25 an icon of national cultural identity, and even a site of political and ideological struggle. For instance, the founding of the French Conservatory of the Far East (Conservatoire Français d'Extrême-Orient) in Hanoi in 1927 was a colonial project intended by the French government to control the indigenous.Footnote 26 The case of the National Conservatory in Shanghai was, however, more complicated. It was founded by Chinese elites, and its name performed the founders’ nationalistic intent. However, its location in the French Concession betrayed its colonial undertone. Its underlying call, I argue, was cosmopolitanism, in the sense that its founders aspired to cosmopolitanism as a way to attain a ‘unity’ of Chinese and Western music.

CAI Yuanpei (Tsai Yuan-pei) (1868–1942) and XIAO Youmei (Hsiao You-mei) (1884–1940), the founders of the National Conservatory in Shanghai, believed that music played an important role in moving China towards what they conceived as a modern society.Footnote 27 As evident in the conservatory's recruitment advertisement, the founders, who were taking other countries’ practices as a model, hoped that the conservatory would unify and synthesize Chinese and Western music. They took the latter as music of the world and maintained that music's ultimate goal was to nourish people's sense of beauty, harmony, and love of art, with datong (Great Unity) as the ultimate objective.Footnote 28 Datong was the Chinese concept of utopia achieved through ideal government, which first appeared in the Confucian classic Liji (The Book of Rites) and was developed by the reformist KANG Youwei (1858–1927) in his volume Datong shu (The Book of Datong). Aside from bestowing music the power to lead to the utopian state, Cai Yuanpei also tried to inspire students to use music to lessen people's sufferings in a speech delivered at the opening of the 1929 school year.Footnote 29

The establishment of a national conservatory in China in 1927 was no doubt a testimony to China's quest for modernity, a project that had started in the late nineteenth century. This quest culminated in the New Culture movement in 1919, which led to broader acceptances of foreign (Western) ideas as well as the adoption of the plain Chinese language. Western music, which had been introduced to the school curriculum as part of the nation's education reform, became even more widespread in large cities in the 1920s and 1930s. The founding of a government-funded music institute to provide systematic and professional Western music training to Chinese youngsters was thus seen by the country's elites as a nationalistic and anti-imperialistic endeavour. Chinese musicians undergoing such training were thought to be able to compete with their Western counterparts on equal grounds to be on a par with Western powers in the cultural arena. This line of thinking is indicative of how colonialism moulded the mindset of the Chinese public at the time. Even though neither Shanghai nor China was fully colonized as some other Asian countries such as Vietnam or the Philippines, colonialism had left an indelible mark on the Chinese psyche. Ironically, colonialism was mapped onto China's national quest for modernity, which is a case in point of the coevality of two contradictory processes, colonialism and nationalism, that could also be seen as cosmopolitanism.

Therefore, it comes as no surprise that Western music thrived at the National Conservatory in Shanghai, even though Chinese music was also a part of the conservatory's programme.Footnote 30 In a few years, it came to have five departments: Theory and Composition, Keyboard (which was originally just piano), Orchestra (which was originally violin, cello, and then other orchestral instruments), Voice, and Chinese music.Footnote 31 The first cohort of students admitted to the National Conservatory was small with only twenty-three students, but the student body grew quickly. Enrolment statistics from 1932 show that 125 students were enrolled. Of these, sixty studied the piano, twenty-five the voice, and twenty the violin. It is noteworthy that Chinese music, theory and composition, and other orchestral instruments attracted fewer than ten students each.Footnote 32 The number bespoke Chinese youngsters’ interest in mastering Western music performance, particularly the piano.

Even though Xiao Youmei aspired to build a music education synthesizing both Chinese and Western traditions,Footnote 33 his two-pronged agenda failed from the start in the face of the ingrained colonial mindset, which meant that the cultural capital accrued by Western music was valued more by Chinese youngsters. As the preceding enrolment statistics point out, it was Western music performance that Chinese youngsters most aspired to learn. Such a trend was closely tied to the rising recognition of Chinese musicians in Shanghai beginning in the late 1920s. Perhaps the most consequential in this regard was a number of Chinese musicians’ performances with the SMO, the city's colonial icon that had been notorious for collaborating only with musicians from European metropolis. The four SMO concerts from 1929 to be discussed in the following section, I would argue, were the performative of a new Shanghai that took advantage of Chinese–Western collaborations.

The SMO's Collaboration with Chinese Musicians

By 1929, Shanghai had grown into a cosmopolitan city. It was home to expatriate and settler communities of different national origins, traditions, and ideologies, while its soundscape was marked by national, ethnic, class, and gender divides.Footnote 34 Among the residents in the city were well-trained musicians from Russia, Germany, and even the United States, who taught instrumental playing not only to Western but also to Chinese youngsters. Chinese elites then were eager to embrace Western music, a cultural asset and a form of cultural capital. Western music reiterated taste and social class on the one hand,Footnote 35 and on the other, it enacted the idea of Chinese modernity, which, for them, meant sharing in the prestige associated with Shanghai's international community.

The four concerts of the SMO that involved collaboration with Chinese musicians not only kindled notions of China's modernity but also performed two conflicting but coeval and intertwined ideals that mapped onto each other: cosmopolitanism and colonialism. These concerts were meant to send a message to the public regarding the core values of cosmopolitan Shanghai, drawing attention towards the Municipal Council's recent receptiveness towards the Chinese public, which had previously been banned from attending SMO concerts in the Town Hall and the public parks (four and two years prior, respectively). The change in the Council's policy was a hard-won battle for the Chinese community, and these exceptional concerts appeared to encapsulate the spirit of a more open and cosmopolitan Shanghai (Table 1).Footnote 36 But often these collaborations could also become a site of colonially tainted Sino-Western relations.

Table 1 SMO concerts with Chinese performers (1927–48)

The dynamics of colonial hierarchy is particularly well exemplified by the 14 May 1929 concert of the SMO's ‘Young People's Concerts’, a series that started in 1926 with the aim of introducing classical music to youngsters in Shanghai. This concert showcased Chinese performers to Shanghai's well-to-do youngsters who studied at ‘Western schools’ reserved for children of Western decent,Footnote 37 corroborating the impression that Chinese youngsters were thriving in the colonial system. The first half of this concert featured Michael Haydn's Toy Symphony, while the second half featured Chinese students of Western pedagogues, namely violinists David C. L. Tai and S. M. Hsu, and flautist J. Y. Lao.Footnote 38 Particularly noteworthy is David Tai (DAI Cuilun) (1912–81), who was to become an important figure of twentieth-century Chinese music.Footnote 39

A similar logic of colonialism shaped the eighth and last concert in the ‘Young People's Concerts’ series. Held on 4 June 1929, it showcased the girls’ choir of the McTyeire Chinese School. The choir sang a work by CHAO Yuenren (1892–1982), a composer and US-trained linguist who was known in Shanghai's Chinese music scene for his Western-style art songs.Footnote 40 The concert was highlighted as a ‘Dance and National Folk-Songs Programme’, a misnomer as the performed works were not genuine folksongs. Such a programme reiterated colonial values by showcasing the Chinese body as accomplished colonial subjects: the Western-trained composer and the girls’ choir of a missionary school were well versed in Western music and successfully assimilated into the colonial society. The McTyeire Chinese School was founded by the American Woman's Council of the Methodist Church in 1890 to provide training for Chinese girls from affluent families who were willing and able to pay considerable tuition for their daughters’ education. Interestingly, the school also provided music training for its students, and by 1916, there were already 112 students learning the piano and four learning the violin. In 1916, the school was also raising funds for yet another building to meet the increasing demands for its programmes.Footnote 41 Given the provision of Western music education at this school, it is not a surprise that its choir was featured at the SMO's Young People concerts, a series started in 1926 with the aim of introducing classical music to youngsters.Footnote 42 Prior to the 1929 concert, the SMO had collaborated with the McTyeire Chinese School choir in 1927 and 1928.Footnote 43

The thirty-second and last concert of the SMO's 1929 concert season featured a Chinese choral society called The Shanghai Songsters.Footnote 44 This concert exemplified a more mutually beneficial connection between the SMO and the Chinese musicians. The Shanghai Songsters was an amateur choral group founded almost a decade before by elite Chinese vocalists of Western music who graduated from local colleges or colleges abroad. As early as in 1921, the group, which was associated with the local YMCA, was reported to have performed Easter music at a local church.Footnote 45 The Songsters was particularly active in 1926, when they came to be known for their many concerts at the Shanghai College as a part of the school's music appreciation initiative.Footnote 46 As mentioned in the North-China Herald, their well-presented programmes were always well received, reflecting the growing popularity of Western music among the Chinese population in Shanghai.Footnote 47 As a matter of fact, the group performed not only choral works but also various Chinese and Western solo vocal works that featured Chinese soloists.Footnote 48

The collaboration between the SMO and the Shanghai Songsters in 1929 was built on prior collaborations. In November 1928, the Shanghai Songsters was part of the SMO's Schubert Festival concert. They joined the Russian choir, creating a choir of eighty-five voices of ‘sonorous sound … that swept across the big Town Hall’.Footnote 49 Together, they performed Schubert's ‘First Love’ and ‘Tender Music All Inviting’. A week after this concert, the SMO joined the Songsters at this vocal group's tenth anniversary concert, which received great acclaim from both the audience and the reviewers.Footnote 50 These collaborations explained why Paci, the director of the SMO, chose to feature the group in a concert that marked the end of the SMO's concert season for 1929.

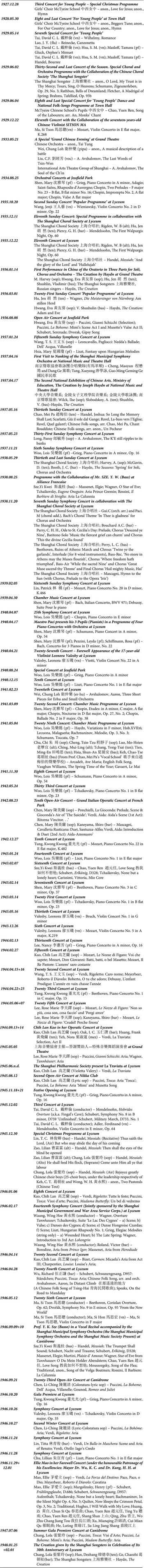

While Paci's importance in the success of the group was overstated by Western critics, the collaboration was a win for both institutions. For the Songsters, working with the SMO meant more recognition as well as the opportunity to sing an expanded repertoire of large-scale works such as Beethoven's Ninth Symphony, Haydn's The Creation, and even Verdi's Stabat Mater. As for the SMO, as mentioned by Paci in his correspondence with the Secretary of the Municipal Council, such choral concerts attracted good audience attendance, and most of all, the Songsters did not charge a fee, unlike the Russian choir.Footnote 51 Two extant photos of the group with Paci in 1929, the first from the June concert and the second from the November concert, show the shifting relationship between the director and the SMO, whether intentionally or accidentally. The first shows Paci as an imposing maestro sitting in front of the choir members at the piano whereas the second shows him as a beloved collaborator sitting among the choir members (Figure 3a and b).Footnote 52

Figure 3a and 3b (Colour online 3a) Mario Paci with the Shanghai Songsters in 1929 (3a: originally published in ‘Photo Standalone 3’, China Press, 24 November 1929, B4. Owing to the poor quality of the original version, the one used here was published in the Chinese magazine Tuhua shibao 570/1 (1929), 1. 3b: ‘Shanghai Songsters to Assist Municipal Concert at Town Hall’, China Press, 27 May 1929, 4.)

The last collaboration between Paci and Chinese musicians in 1929 took place during the SMO concert on 22 December, which counted as a part of the 1930 concert season. It involved the seventeen-year-old MA Sicong (spelled Sitson Ma in Shanghai newspapers and Ma Tzu-tsung in New York Times), who was to play Mozart's Violin Concerto in E flat major, K. 268.Footnote 53 Ma had already made an appearance in Shanghai's music scene by appearing in Songsters’ annual concert three weeks before the advertised collaboration with the SMO.Footnote 54 His SMO debut was highly anticipated in the Chinese community as the SMO had never featured a Chinese soloist in its regular concerts – a fact noted in advertisements in various newspapers. Ma was a rare case of success in Western instrumental playing at this time, and to some extent, this was due to early education. His brother took him to France when he was 11. He started to learn the violin at 12, entered a regional conservatory at 13, and studied at the Paris Conservatory at 15. When Ma came back to China in 1929 at the age of 17, he was hailed by the Chinese media as a ‘wonder boy’. He was reported to have played in Guangzhou and Nanjing and to have been invited to play in Japan as well.Footnote 55 Ma's fame and his great reception at the Songsters concert must have prompted Paci to give him a chance to play with the SMO.

Whether Ma's concert was successful and whether it had actually taken place is a mystery as there was no further mention of the event at all. What remains in record from around this time is an announcement of a concert at the Town Hall in January, not with the SMO but with other Chinese musicians.Footnote 56 Regardless of exactly what had happened, it appears that Ma ultimately saw himself as a composer rather than a concert violinist. The fact that he changed his career path to study composition from 1931 to 1932 at the Paris Conservatory was telling of how he felt about his own talent in violin performance.Footnote 57

Ma's collaboration with the SMO was probably not a successful one, and the SMO did not collaborate with any more Chinese soloists until several years later. According to my study of the SMO programmes, those who were deemed good enough to appear repeatedly with the SMO included Mary Xia, Lois Woo, SZE Yi Kwei, Leonora Valesby, TUNG Kwong Kwong, and KAO Chih Lan, and these Chinese musicians did turn out to be successful performers (see Table 1). Woo and Kao became leading pedagogues in China while Sze went on to attain an international career as an operatic bass-baritone and taught at the Eastman School of Music.Footnote 58

In this regard, the SMO's collaborative concerts with Chinese musicians, which showcased the Chinese body in performance, were a performative site of power negotiations. On the one hand, these concerts helped the SMO to enact the promise of cosmopolitanism as well as to expand its audience pool. On the other, they provided Chinese musicians the opportunity to play with the only professional orchestra in China at the time, even though, as I emphasized with the first two examples, their representation could be mediated by colonial hierarchy. These collective performances were indeed deemed moments of glory by the musicians and audiences of the time, and they laid the path for a trajectory of Western music in China.

Chinese Performing Western Music

The attention Chinese musicians received from their collaborations with the SMO encapsulated the intersection of cosmopolitanism, colonialism, and nationalism in colonial Shanghai. Different actors and communities bestowed the endeavours with different meanings, each taking advantage of the opportunities afforded by such collaborations. Western music concerts by Chinese musicians also gained recognition from Shanghai's Western communities as testified by reports of them in English, French, German, and even Russian newspapers to be discussed shortly. Xiao Youmei, the co-founder and president of the National Conservatory, was quite aware of the importance of music performance to the reputation of the institution. A small recital by its faculty members was organized for the conservatory's inauguration as well as its first anniversary celebration. The first joint student concert was held in May 1930 and thereafter annually.Footnote 59 Overseen by the conservatory's Concert Committee, other performances of the conservatory included students’ graduation recitals, faculty concerts, as well as ad hoc concerts devoted to a special purpose, which were sometimes covered by Shanghai's newspapers. Interestingly, these were covered more often by Western newspapers than Chinese-language ones.

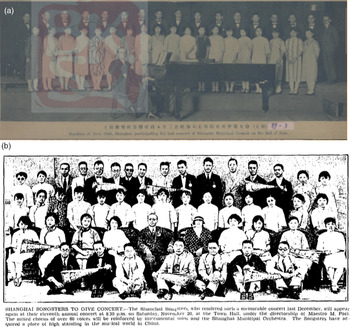

One such example concerned the first cohort of the conservatory's graduates – CHIU Foo Sung, LEE Hsien Ming, and YU I Hsung covered in the China Press in 1933.Footnote 60 Aside from documenting the performances, these English newspaper reports testified to the international community's recognition of Chinese musicians taking part in initiatives associated with Western classical music. Chiu Foo Sung was said to have given a piano recital at the University of Shanghai to bring classical music to university students. Lee Hsien Ming, the future wife of the Russian émigré composer and pianist Alexander Tcherepnin,Footnote 61 was reported to have played at the American Women's Club.Footnote 62 Yu was said to have sung at the annual meeting of the National Child Welfare Association of China and a charity ball in aid of the China Mission to Lepers,Footnote 63 the former an NGO with a New York connectionFootnote 64 and the latter a subsidiary of the Mission to Lepers in the United Kingdom and the United States.Footnote 65 Since Chiu and Lee were students of the renowned Russian pedagogue Boris Zakharov, their graduation was also reported in the Russian newspaper Shanghai Zaria in great length with an eye-catching photo of the students with their teacher (Figure 4), clearly affirming Russian musicians’ contribution to the Shanghai community.Footnote 66 In the North China Daily News, the success of the students was hailed as a testimony to Western music's universality – ‘music, the universal language, can lift the curse of Babel’.Footnote 67

Figure 4 (Colour online) Boris Zakharov with CHIU Foo Sung, LEE Hsien Ming, 1933 (‘B.S. Zakharov i laureaty: Istoricheskii vypusk Natsionalnoi Konservatorii’ (‘Professor B.S. Zakharov and his prize-winners: Historic graduates of the National Conservatory’). Shankhaiskaia Zaria, 7 July 1933, 6).

The visibility of the conservatory's students in the media was due to their prowess in musical skills. Those who completed the entire curriculum were said to be in great demand due to the burgeoning of Western music programmes at various regional tertiary educational institutions.Footnote 68 In this regard, it is interesting to note how students benefited from Shanghai's unique context. Almost half of the performance staff of the conservatory were graduates of the Saint Petersburg Conservatory. This not only reflected Xiao Youmei's determination to have the best staff possible but also the relocation of many Russian émigrés to Shanghai from Harbin and other cities fleeing the revolution after 1925. The rapid development of the piano and vocal departments was in part due to two of the renowned Russian pedagogues at the conservatory – Boris Zakharov and Vladimir Shushlin. They brought their performance skills and musical knowledge to Chinese students and were hailed as forefathers of Chinese pianism and bel canto respectively.Footnote 69 The conservatory also benefitted from the players of the SMO, including its concert master Arigo Foa and the cello principal Igor Shetzov, as well as the principals of the wind and brass sections.Footnote 70

WU Leyi (Lois Woo), the star student at the conservatory mentioned at the beginning of this article, exemplified Shanghai's cosmopolitan ideals as she embodied moments of collaboration between the SMO and the National Conservatory. At Wu's debut with the SMO in November 1937, she played Grieg's Piano Concerto.Footnote 71 Her performance must have been a great success as she was again featured at the Red Cross concert just three weeks later. The year 1940 was even more triumphant for her as she played in three SMO concerts, and then in the following few years, she played repeatedly, covering almost all major repertoire of the piano concerto literature.Footnote 72 Wu later became one of the leading pianists of the PRC and eventually, a famous pedagogue of the Shanghai Conservatory, its predecessor being the National Conservatory.

While there was no visual documentation of Wu's performance with the Municipal Orchestra, there was one featuring GAO Zhilan, a vocal student at the conservatory. This photo, likely from a concert from 1944 or 1945,Footnote 73 showcased her in front of one of the most powerful icons of Shanghai whose players were largely European (Figure 5).Footnote 74 The photo was and is a performative of national glory from a Chinese perspective, a testimony to the ‘Chinese can do’ spirit, the so-called ‘wei guo cengguang’ (meaning literally ‘bringing glory to the nation’). In fact, a newspaper report treating a similar concert – the pianist Mary Xia's performance with the Municipal Orchestra in 1937 – used the phrase ‘Brings considerable glory to our nation’ in the title.Footnote 75

Figure 5 GAO Zhilan with the Shanghai Municipal Orchestra, 1945.

Therefore, it is fair to assume that the Chinese musicians’ high-profile performances were not merely concerts but performative acts of an array of political, social, and cultural expectations and assumptions that suggested negotiations at many different levels that had a profound impact on Chinese youngsters at the time. A moment on the SMO stage, I gather, must have inspired Chinese youngsters to contemplate a career in music, which used to garner little to no respect due to folk musicians’ low social status.

Even those less successful conservatory students who collaborated with the SMO were to become important musical figures of the PRC, Taiwan, and Hong Kong. Their contribution to Chinese musical development would have happened with or without the SMO concerts in which they took part. But the recognition they got from an iconic institution of Western music-making in China, I assume, must have also meant something to them and those who followed their footsteps, thanks to the performative power of music performance.

The Performativity of Music Performance

As shown previously, Western music performance accrued an array of meanings in Shanghai with the change of time. It was a performative act of colonial power and sovereignty when it was first brought to the Chinese territory. But as it began to take root and was practised by Chinese musicians in the course of the 1920s and 1930s, it came to enact ideals of Chinese modernity and nationalism. At the same time, Shanghai's international community also came to regard Western music performance as an act of cosmopolitanism, in response to the socio-cultural changes in the city.

As I have demonstrated, SMO's concert programming reflected such a change in the zeitgeist. In addition to the concerts already analysed, we can turn to the Chinese premiere of the choral movement of Beethoven's Symphony No. 9, which took place on 7 April 1936 at the Grand Theatre. The orchestra showcased the collaboration of various Shanghai's vocal ensembles, such as the Shanghai Choral Society (which consisted of Westerners), the Shanghai Songsters (exclusively Chinese), a group of German vocalists, and Mashin's Russian choir.Footnote 76 Privately, Paci complained about the extra rehearsals that this entailed,Footnote 77 and it is not clear how much interaction singers from each of these communities had with one another and whether such interaction would have actually helped to improve racial harmony. Nevertheless, the different choirs singing Beethoven's ‘Ode to Joy’ on the same stage would have been understood as a display of Shanghai's cosmopolitan aspirations.

Other collaborative concerts can be understood as sites in which multiple meanings were negotiated as they were charged with an array of explicit and implicit intentions among the performers and the audiences. In this regard, it is worthwhile revisiting the ‘Red Cross Drive’ fundraising concert mentioned at the beginning of this study.Footnote 78 As a benefit concert that sought to raise $100,000 for the Red Cross's work to help the victims of the Sino-Japanese war, the event exhibited international cooperation and human benevolence as the causes of Shanghai's cosmopolitan community. This was no doubt a cosmopolitan gesture, testifying to the goodwill of Shanghai's international and Chinese residents.

From a Chinese perspective, such a concert was also an act of nationalism, an act to bring ‘face’ to a China that at the time was being looked down on as ‘backward’. Further research reveals that it was a ‘Mrs. Ernest S.H. Tong, assisted by a group of foreign and Chinese members of the younger social set’ who was behind the scene.Footnote 79 Presumably, it was because of this Chinese woman's financial support and the multi-racial scope of the audience (i.e., both Western and Chinese residents in Shanghai) that the concert programme highlighted Chinese identity. This was reflected in the programming as well: the concert included traditional Chinese music by the Chaozhou (Shao-Chao) ensemble and Avshalomov ‘Chinese’ ballet. Moreover, the concert displayed Chinese musicians as practitioners of Western music sharing the same stage with the Municipal Orchestra.

But when scrutinized, particularly when taking into consideration Sedgwick's notion of periperformative,Footnote 80 a colonial undertone emerged within the discourses that clustered around the performative. Advertised as a ‘treat of extravaganza’, the concert framed Chinese elements, the two Chinese pieces the pipa solo Downfall of Chu and the ensemble piece Moonlight of Chingyang by members of the Shao-Chao Institute, as ‘exotic’ so as to appeal to the taste of the city's cosmopolites in 1930s Shanghai. In fact, just a few years prior to this concert, the Municipal Orchestra had organized a special concert of Chinese themes that featured Avshalomov's works,Footnote 81 mistaking these as ‘Chinese’ music.

And there is yet another layer of meaning. The Red Cross was in Shanghai due to the Sino-Japanese War, which had started in August 1937. In December 1937, China's capital Nanjing was under Japanese attack. Many Chinese in Shanghai, particularly students, reacted to Japan's invasion with large-scale protests in December. These demonstrations interfered with the Red Cross's fundraising efforts, as elusively mentioned in various newspaper reports prior to the concert. In this regard, it is interesting to note that the date the concert was held came to be known in Chinese history as the 12.8 Incident, which commemorates China's struggle against the Japanese invasion. In light of this history, the concert was a testimony to Shanghai foreign settlement's neutrality and its ‘cosmopolitan’ attitude towards the war, which must have appeared apathetic to the Chinese side. The Chinese elements in the concert – be it the performance of ‘nationalism’ or ‘cosmopolitanism’ – were as intricate and ideologically complex as the many incidents surrounding it. In particular, it cannot be missed that any notion of Chinese accomplishment validated through this concert would also have to accept that such accomplishments were enacted according to Western terms.

Finally, from the perspective of Chinese elites, the embrace of Western music in a concert such as the Red Cross one stood for China's step towards modernity.Footnote 82 Such a development can be understood as a consequence of societal changes, most importantly, the rise of urban culture and capitalism following the entry of Western empires into China. If modernism in the West was the zeitgeist of the early twentieth century, embracing Western culture, known in China as modernity, was China's response to the socio-political changes wrought by imperialism.

Conclusion

The recognition of Chinese musicians as performers of Western music in interwar Shanghai came at a juncture in China's history when looking towards the West was deemed by the country's cultural leaders as an act of ‘self-strengthening’ and a necessary step in ‘catching up’ with the West. As Western music was deemed ‘new music’ and traditional Chinese music was dubbed ‘old’, it is not a surprise that many youngsters chose to follow the Shanghai musicians’ footsteps. Indeed, many of them devoted themselves to the performance of ‘new music’ without questioning its validity and relationship to Chinese identity in the Chinese context. We must not overlook the profound impact of these early performances of Western music by Chinese musicians on China's musical trajectory. Had these musicians not gained the success and recognition they did, China's musical path might have taken a different turn.

Rather than criticizing or defending such a developmental path, I underscore the need to look at Chinese musicians’ performance of Western music then as well as now holistically. And this is not a call to abandon traditional music as the object of scholarly inquiry. Traditional Chinese music is worthy of protection and research, but such endeavours should not be done at the exclusion of Western music in China in scholarship, an exclusion that has often been a feature of ethnomusicology in the West.Footnote 83 The trajectory of Western music in China must be understood in an historical context: simply said, it was adopted when the nation and its people were subjected to larger socio-political forces from within and beyond in the early twentieth century, a period often identified in PRC discourse as a century of humiliation.

Music performance has always carried layers of meanings for those who produced and consumed it. As a performative act of identity, beliefs, and aspirations, and at the same time, of racial divide, power negotiation, and good will, musical meaning is dependent on how it is constructed and by whom it is constructed. Imported music such as Western music in Shanghai, Korea, and Vietnam, while mostly overlooked in music literature in the West, carries complex and often distinct meanings to the local people and to Asian scholars, meanings that may not be as visible to the settlers and Western scholars. Given the gaps that this difference has created in Anglophone music scholarships, what is important to explore now is how different types of ‘new’ music became sites of cultural convergences and negotiations for the many parties involved in their productions and consumptions as demonstrated by all the articles in this special issue of the journal. Hyun Kyong Hannah Chang points out in her prior study of Korean Christian music in Korea that Christian musicking in early twentieth-century Korea ‘formed a complex site’ that testified to the convergence of North American religious practices and Korean social mobilization. Rather than regarding it as a mimesis of or opposition to the West, she heard this music as a trans-Pacific Korean voice and genealogy, through which the Korean Christians participated in a ‘global history’, despite their compromised positions and the shifting power relationships with those involved in the process.Footnote 84 In the same vein, I also hear Chinese musicians performing Western music in interwar Shanghai not as a mimesis of the West, but as a cosmopolitan aspiration to participate in a global musical network and acts of power negotiation in the context of semi-colonial Shanghai.

With this study of Western music concerts of Chinese musicians in interwar Shanghai during the interwar period, I hope to have shown the performativity of music performance – how it had ‘performed’ an array of ideologies, beliefs, aspirations, and desires, and negotiated identities and power relations. In the same vein, I suggest, any performance today, if subjected to careful study, would reveal a network of performatives and periperformatives, from which we can learn more about who we were/are and the society we lived/live in. As pointed out by Victor Turner:

if man is a sapient animal, a toolmaking animal, a self-making animal, a symbol-using animal, he is, no less, a performing animal, Homo performans, not in the sense, perhaps that a circus animal may be a performing animal, but in the sense that a man is self-performing animal – his performances are, in a way, reflexive, in performing he reveals himself to himself. This can be in two ways: the actor may come to know himself better through acting or enactment; or one set of human beings may come to know themselves better through observing and/or participating in performances generated and presented by another set of human beings.Footnote 85