Psychotic experiences, of which hallucinations are most frequently endorsed,Reference McGrath, Saha, Al-Hamzawi, Alonso, Bromet and Bruffaerts1 are reported by approximately 5% of adults,Reference McGrath, Saha, Al-Hamzawi, Alonso, Bromet and Bruffaerts1–Reference Suetani, Mamun, Williams, Najman, McGrath and Scott3 8% of teenagers and 17% of pre-teensReference Maijer, Begemann, Palmen, Leucht and Sommer2,Reference Linscott and van Os4,Reference Newbury, Arseneault, Beevers, Kitwiroon, Roberts and Pariante5 in the general population. Multiple studies, mainly in young people, have shown a strong relationship between hallucinations and a wide variety of mental disorders, as well as suicidal ideation, suicide attempts and suicide deaths.Reference Healy, Brannigan, Dooley, Coughlan, Clarke and Kelleher6–Reference Yates, Lang, Cederlof, Boland, Taylor and Cannon9 Interestingly, research has shown that the psychopathologic significance of hallucinations varies across developmental stages in childhood and adolescence. Hallucinations become less prevalent as children enter adolescence,Reference Kelleher, Connor, Clarke, Devlin, Harley and Cannon10 but, conversely, become more predictive of psychopathology with age.Reference Kelleher, Keeley, Corcoran, Lynch, Fitzpatrick and Devlin7 The psychopathologic significance of hallucinations across the adult lifespan is less clear. Although a number of studies have suggested that the prevalence of hallucinations decreases with ageReference Maijer, Begemann, Palmen, Leucht and Sommer2,Reference Kelleher, Connor, Clarke, Devlin, Harley and Cannon10–Reference Larøi, Bless, Laloyaux, Kråkvik, Vedul-Kjelsås and Kalhovde12 there has, to our knowledge, been no research to investigate the relationship between hallucinations and mental disorders across the adult lifespan. Using data from the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey (APMS) series, originally carried out in a large UK general population sample in 1993, and repeated in 2000, 2007 and 2014, we calculated the prevalence of hallucinations in the general population from 16 to 95 years of age. We assessed for age-related variation in the prevalence of hallucinations and investigated the relationship between hallucinations and a range of mental disorders, including depression, phobia, panic disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), mixed anxiety and depression, and generalised anxiety disorder, as well as suicidal ideation and suicide attempts.

Method

The APMS series is the longest running cross-sectional study in the world, and uses consistent methods to assess the prevalence of a range of mental disorders and related factors in the general population. The study began in 1993, and has been repeated at 7-year intervals since (2000, 2007 and 2014). The consistent methods allow different study waves to be combined to allow robust testing of hypotheses, using large samples. The studies have involved multi-stage probability samples of private households. The 1993 and 2000 surveys were conducted by the Office of National Statistics, and the 2007 and 2014 surveys were carried out by NatCen Social Research in collaboration with the University of Leicester.

For the purposes of the current study, we combined data from the 1993, 2000, 2007 and 2014 APMS cohorts. The 1993 study collected data on individuals aged 16–64 years in England, Scotland and Wales, and the 2000 study collected data from individuals aged 16–74 years in England, Scotland and Wales. The 2007 and 2014 studies collected data from England only, from age 16 years, with no upper age limit.

The surveys used a two-phase interview approach. During the first phase, trained interviewers collected data on demographic information, service use, social variables and a number of physical health conditions and common mental disorders. In the second phase, clinically trained interviewers collected data on traumatic experiences, suicidality and self-harm behaviours and psychotic experiences. Participants gave verbal informed consent before completing the phase one interview, and again at the phase two interview. Participants were also asked to provide written informed consent for their data to be linked to other health information and to take part in any survey follow-up. This written consent was collected after the phase one interview and again after the phase two interview. For full APMS methods see McManus et al.Reference McManus, Bebbington, Jenkins and Brugha13

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All procedures involving human patients were approved by the London Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee and the 149 local research ethics committees which were responsible for the addresses selected in the sampling process (the 2000 survey); The Royal Free Medical School Research Ethics Committee (2007 survey, reference number 06/Q0501/71) and the West London Research Ethics Committee (2014 survey, reference number 14/LO/0411). Ethical approval was not required for the 1993 APMS.

Measures

Hallucinations

The following question from the Psychosis Screening QuestionnaireReference Bebbington and Nayani14 was used to assess hallucinations: ‘Over the past year, have there been times when you heard or saw things that other people couldn't?’. Questionnaire items on auditory and visual hallucinations have been shown to have high positive and negative predictive value for symptoms verified in clinical interviews.Reference Kelleher, Harley, Murtagh and Cannon15,Reference Gundersen S, Goodman, Clemmensen, Rimvall, Munkholm and Rask16

To ensure our findings were not simply attributable to psychotic disorders, we ran analyses excluding individuals with a psychotic disorder or probable psychotic disorder. However, for the sake of completeness, we have also included supplementary analyses including individuals with a psychotic disorder or probable psychotic disorder (see Supplementary Figs 1–11, Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2021.100). A diagnosis of psychotic disorder was based on assessment with the Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (SCAN).Reference Wing, Babor, Brugha, Burke, Cooper and Giel17 Participants were invited for SCAN assessment if they had any of the following: current antipsychotic use, history of psychiatric hospital admission, self-reported diagnosis or symptoms suggesting a psychotic disorder, or a positive response to the question, ‘Did you at any time hear voices saying quite a few words or sentences when there was no one around that might account for it?’. For individuals who were invited to, but did not complete the SCAN, a diagnosis of ‘probable psychosis’ was assigned if they endorsed two or more of the above screening criteria.

Mental health outcomes

The Clinical Interview Schedule – Revised (CIS-R) was used to assess the past-week prevalence of the following diagnoses (defined according to the ICD-10 criteria): depression, phobia, panic disorder, OCD, mixed anxiety and depression, and generalised anxiety disorder.Reference Brugha, Bebbington, Jenkins, Meltzer, Taub and Janas18 An ‘any mental disorder’ variable was also created. It also provides a total CIS-R score that reflects the severity of past-week mental health symptoms.

Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts were assessed in the 2000, 2007 and 2014 data-sets with the following questions: ‘Have you ever thought of taking your life, even if you would not really do it?’ and ‘Have you ever made an attempt to take your life, by taking an overdose of tablets or in some other way?’.Reference McManus, Bebbington, Jenkins and Brugha13,Reference McManus, Meltzer, Brugha, Bebbington and Jenkins19

Statistical analysis

We calculated the prevalence of hallucinations and mental disorders with data from the 1993, 2000, 2007 and 2014 data-sets, using the following age ranges: 16–19, 20–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69 and ≥70 years. We calculated the prevalence of suicidal ideation and suicide attempt in the same age ranges, using the combined 2000, 2007 and 2014 data-sets (the 1993 data-set was excluded as it did not include the necessary data on suicidal ideation and attempts).

Because some age groups had low numbers of individuals with suicidal ideation or attempt, we collapsed the seven age groups into the four following age groups, for the purposes of looking at the relationship between hallucinations and suicidal behaviour: 16–29, 30–49, 50–69 and ≥70 years. For each age category, we used logistic regression to assess the relationship between hallucinations and mental disorders, suicidal ideation and suicide attempts.

We used presence (yes/no) of mental disorders, suicidal ideation and suicide attempt as an outcome, and hallucinations (yes/no) as predictor to look at the association in each age group separately. To assess whether any difference in the odds of suicidal ideation or suicide attempt in individuals with hallucinations was explained by severity of general psychopathology, we repeated the analyses adjusted for the total CIS-R score. To assess whether there was a significant difference in prevalence of mental disorder, suicidal ideation and suicide attempt across these age groups, we ran logistic regressions with the i. command in Stata/SE 14 for Windows, and compared the prevalence in each age category to the prevalence in the previous age category.

To test for a linear increase or decrease in the strength of the relationship between hallucinations and the three outcomes (mental disorders, suicidal ideation and suicide attempt) across age groups, we used the Stata command ‘nptrend’, a nonparametric test for trend across ordered groups.

Because approximately 15% of individuals over 85 years of age are in non-private residences,20 such as nursing homes, we wanted to be sure that results in our ≥70 years age group were not driven by selective attrition of less healthy individuals from the general population of private residences. Therefore, we carried out sensitivity analyses excluding individuals aged 80–95 years (i.e. including only individuals aged 70–79 years in the oldest cohort), to see whether the same trend persisted. See Supplementary Fig. 12, Supplementary Tables 3 and 4).

The 2000, 2007 and 2014 data-sets were weighted to take into account participant non-response and selection. Data were weighted to match the population in terms of age×gender and region. Information on how the data were weighted can be found at: http://doc.ukdataservice.ac.uk/doc/8203/mrdoc/pdf/8203_apms_2014_user_guide.pdf.

All analyses were conducted using Stata/SE version 14, and were adjusted for cohort effects.

Results

General descriptive statistics

The 1993 (N = 10 108), 2000 (N = 8580), 2007 (N = 7403) and 2014 (N = 7546) data-sets were combined, with a total sample size of 33 637 (56% female). The age of participants ranged from 16 to 95 years. The mean age of respondents was 46.6 (s.d. 17.2). In total, 245 participants (0.73% of the sample) met criteria for psychotic disorder or probable psychotic disorder.

Prevalence of hallucinations across age

In total, 1376 individuals (4.24%) reported hallucinations within the past year, 58.2% of whom were female. There was a significant decreasing trend of hallucination across the seven age groups (z = −6.83, P < 0.001; see Fig. 1(a)). Overall, there was a significant decrease in the prevalence of hallucinations between individuals aged 16–19 years and 20–29 years, no significant difference between individuals in the next three age groups, followed by a significant decrease in prevalence of hallucinations between individuals aged 50–59 years and 60–69 years, and then another significant decrease in individuals aged ≥70 years. There was a significant decreasing trend of hallucinations across the seven age groups for males (z = −5.16, P < 0.001) and females (z = −4.61, P < 0.001). See Supplementary Fig. 14 for prevalence of hallucinations across age, stratified by gender.

Fig. 1 (a) Prevalence of hallucinations by age and (b) prevalence of mental disorder by age and hallucinations.

Prevalence of mental disorders across age

In the total sample, 5668 individuals (16.97%) had at least one mental disorder, 66.1% of whom were female. There was a significant increase in the prevalence of mental disorder between ages 16–19 years and 20–29 years, and then a significant decrease in the prevalence of mental disorder for each subsequent age group compared with the previous age group (see Fig. 1(b)). There was a significant decreasing trend of mental disorders across the seven age groups for males (z = −4.68, P < 0.001) and females (z = −10.23, P < 0.001). See Supplementary Fig. 14 for prevalence of mental disorder across age, stratified by gender.

Prevalence of suicidality across age

Suicidal ideation

In the total sample, 3924 individuals (16.81%) reported lifetime suicidal ideation, of which 62.7% were female. There was no significant decrease in the prevalence of suicidal ideation from 16–29 years to 30–49 years, followed by a significant decrease in prevalence from 30–49 years to 50–69 years, and another significant decrease from 50–69 years to ≥70 years (see Fig. 2(a)). There was a significant decreasing trend of suicidal ideation across the seven age groups for males (z = −9.67, P < 0.001) and females (z = −14.25, P < 0.001). See Supplementary Fig. 15 for prevalence of suicidal ideation across age, stratified by gender.

Fig. 2 (a) Prevalence of suicidal ideation by age and hallucinations and (b) prevalence of suicide attempt by age and hallucinations.

Suicide attempt

In the whole sample, 1256 individuals (5.38%) reported at least one lifetime suicide attempt, of which 67.1% were female. There was a significant decrease in prevalence of suicide attempt between each age group when compared with the previous age group (see Fig. 2(b)). There was a significant decreasing trend of suicide attempt across the seven age groups for males (z = −5.26, P < 0.001) and females (z = −9.58, P < 0.001). See Supplementary Fig. 16 for prevalence of suicide attempt across age, stratified by gender.

Psychopathologic significance of hallucinations

Prevalence of mental disorder across age, by hallucinations

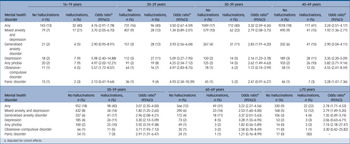

Individuals who reported hallucinations had a three to five times greater odds of having at least one mental disorder compared with individuals in the same age group who did not report hallucinations (see Table 1). There was a significant decreasing trend of having at least one mental disorder across the seven age groups in individuals with hallucinations (z = −2.81, P = 0.005). Females who reported hallucinations had a three to five times greater odds of having at least one mental disorder compared with females in the same age group who did not report hallucinations; males had a three- to four-fold increase in odds. See supplementary analyses for gender-stratified results (Supplementary Table 5).

Table 1 Prevalence of mental disorder across age groups, by hallucinations

a. Adjusted for cohort effects.

Relationship with suicidal ideation and attempts

Across all age groups, individuals who reported hallucinations had increased odds of lifetime suicidal ideation and lifetime suicide attempt compared with individuals in the same age group who did not report hallucinations (see Table 2). There was a significant decreasing trend of suicidal ideation across age in individuals with hallucinations (z = −4.44, P < 0.001), and a significant decreasing trend of suicide attempt across age in individuals with hallucinations (z = −3.53, P = 0.002). See supplementary analyses for analysis stratified by gender (Supplementary Tables 7 and 8), where results also show an increased odds in both males and females.

Table 2 Prevalence of suicidal ideation and attempt across age, by hallucinations

a. Adjusted for cohort effects.

b. Adjusted for gender and cohort effects.

c. Adjusted for gender, cohort effects and total Clinical Interview Schedule – Revised score.

Discussion

In a large general population study, we found that the prevalence of hallucinations varied significantly across the adult lifespan, from a high of 7% in individuals aged 16–19 years (the youngest age group) to a low of 3% in individuals aged ≥70 years (the oldest age group). Our findings mirror paediatric research in that hallucinations also decline in prevalence from childhood into adolescence, from a meta-analytic prevalence of 17% in children (ages 9–12 years) to 8% in adolescents (ages 13–18 years).Reference Kelleher, Connor, Clarke, Devlin, Harley and Cannon10 Our findings show that there is significant life-course developmental variation in hallucination prevalence extending into adulthood.

Previous research on adults in the general population has reported a wide variation in the prevalence of hallucinations, depending on study methodological differences.Reference Kråkvik, Larøi, Kalhovde, Hugdahl, Kompus and Salvesen21,Reference Turvey, Schultz, Arndt, Ellingrod, Wallace and Herzog22 These methodological differences make it difficult to validly compare hallucination prevalence between age groups in different studies. A strength of the current study is that it used consistent methods to assess hallucination prevalence across the adult lifespan, meaning that we could directly compare age groups. Hallucination prevalence was largely consistent across early and middle adulthood, but significantly declined in individuals aged 60–69 years and again in individuals aged ≥70 years.

In addition to age-related variation in the prevalence of hallucinations across the adult lifespan, there was also age-related variation in the psychopathologic significance of hallucinations. There was little variation in the strength of the relationship between hallucinations and mental disorders across early adulthood and middle adulthood. For individuals aged 16–59 years, approximately 40% of individuals who reported hallucinations had one or more cooccurring mental disorder. This relationship attenuated for individuals aged 60–69 years, just over 30% of whom had one or more cooccurring mental disorder, and again for individuals aged ≥70 years, just over 20% of whom had one or more cooccurring mental disorder.

Similarly, for suicidal ideation and suicide attempt, there was a significant change across the full adult lifespan. For individuals aged 16–49 years, approximately 45% of individuals who reported hallucinations also reported suicidal ideation. This decreased for individuals aged 50–69 years, where 36% reported suicidal ideation, and decreased again for individuals aged ≥70 years, where 20% reported suicidal ideation.

For suicide attempt, there was a significant decrease in prevalence between each age group. Approximately 22% of individuals with hallucinations in the youngest age group (16–29 years) reported at least one lifetime suicide attempt. This significantly decreased to 19% of individuals aged 30–49 years with hallucinations, and decreased again to 14% of individuals aged 50–69 years with hallucinations. This decreased further in the oldest age group (≥70 years) with hallucinations, in which <10% reported a lifetime suicide attempt.

There are a number of potential reasons for declining prevalence of hallucinations with age, as well as for the developmental variation observed in the psychopathologic significance of hallucinations. For one, brain maturation processes from middle age to old age may play a role in the reduced prevalence of hallucinations in older adults.Reference Isaac Tseng, Hsu, Chen, Kang, Kao and Chen23,Reference Sala-Llonch, Bartrés-Faz and Junqué24 For example, there is structural re-organisation of brain networks from middle adulthood to old ageReference Wu, Taki, Sato, Kinomura, Goto and Okada25 that potentially results in weakened functional segregation and integration,Reference Zhang, Wang, Chen, Guo, Wang and Chen26 which may reduce the prevalence of hallucinations in older adults.Reference Stephane, Barton and Boutros27 From a psychosocial perspective, research suggests that older adulthood is associated with the development of a number of skills that may reduce risk of hallucinations or their psychopathologic effects. For example, studies have shown that maladaptive coping skills and high levels of emotional dysregulation increase the risk of hallucinations,Reference Lin, Wigman, Nelson, Vollebergh, van Os and Baksheev28,Reference Wigman, Devlin, Kelleher, Murtagh, Harley and Kehoe29 which are factors that are known to improve as adults age.Reference Luong and Charles30,Reference Livingstone and Isaacowitz31

Strengths and limitations

The major strength of our study was the ability to look at hallucination prevalence across the full adult lifespan, from 16 years onward. The APMS series used consistent methods in assessing hallucinations, mental disorders, suicidal ideation and suicide attempts, allowing different waves of the study to be combined, resulting in a large sample size. The data-sets were cross-sectional in nature, which means that one cannot carry out longitudinal analyses of the relationships between variables of interest; however, that does not detract from the value of investigating important contemporaneous relationships between hallucinations, age and various mental health factors. A limited number of mental disorders were assessed in this study, and future research might like to include a wider range of mental disorders. Single questions were used to assess suicidal ideation, suicide attempts and hallucinations. Our clinical interest was in the psychopathologic significance of hallucinations, although other researchers may like to look at a broader range of psychotic experiences. Our results are generalisable to adults living in private residences in the community. It will be important for future research to include non-private residences to clarify the psychopathologic significance of hallucinations in other settings, including with regard to hallucinations in the context of dementia.

Implications

Using consistent measures in a large general population sample from ages 16 to 95 years, we found that the past-year prevalence of hallucinations significantly declined with age, from 7% in individuals aged 16–19 years to 3% in individuals aged ≥70 years. Hallucinations were associated with increased risk for mental disorders, suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in all age groups. At the same time, we found age-related variation in the strength of these associations, with hallucinations more strongly associated with psychopathology, suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in early adulthood and middle age, compared with later life. Our findings highlight that there are important life-course developmental features of hallucinations that vary from early adulthood to old age, which should inform clinicians working with adults of different ages.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2021.100

Data availability

The 1993 data that support the findings of this study are openly available in The UK Data Service at http://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-3560-1. The 2000 data that support the findings of this study are openly available in The UK Data Service at http://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-4653-1. The 2007 data that support the findings of this study are openly available in The UK Data Service at http://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-6379-2 The 2014 data that support the findings of this study are available from NHS Digital. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under licence for this study. Data are available The UK Data Service at http://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-8203-2, with the permission of NHS Digital.

Acknowledgements

We thank NHS Digital for granting us permission to use the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey data. We also acknowledge Fiona Boland in the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland Data Science Centre, for providing statistical advice and support.

Author contributions

K.Y. and I.K. were responsible for conception or design of the work. All authors were responsible for the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data. K.Y., U.L., H.O. and I.K. drafted the manuscript. E.M.P., J.T.W.W., F.M., M.C., J.D. and H.R. revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published. K.Y., H.O. and I.K. agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding

K.Y. and U.L. were supported by a Strategic Academic Recruitment (StAR) award to I.K. from the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland. M.C. was funded by a European Research Council Consolidator Award (number 724809, project iHEAR). I.K. was funded by the Irish Health Research Board (grant number ECSA-2020-05), and St John of God Research Foundation (project grant 2021). J.T.W.W. was funded by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (Veni grant number 016.156.019). Funding sources had no involvement in the study design; collection, analysis or interpretation of the data; in writing of the manuscript or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Declaration of interests

The authors did not take part in the review or decision-making process of this paper. M.C. is a member of the BJPsych editorial board. M.C. did not take part in the review or decision-making process of this paper.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.