Background

Bipolar disorder is highly heritable and affects approximately 1% of the population. It has a recurrent or chronic course and is associated with psychosocial impairment and reduced functioning, and it is a leading cause of global disease burden.Reference Cloutier, Greene, Guerin, Touya and Wu1 Individuals usually experience their first (hypo)manic or depressive episode of bipolar disorder in adolescence or early adulthood, but often they are not diagnosed until 5 to 10 years later,Reference Berk, Dodd, Callaly, Berk, Fitzgerald and de Castella2 especially in individuals with an earlier age at onset (AAO) or a depressive index episode.Reference Dagani, Signorini, Nielssen, Bani, Pastore and Girolamo3 Early illness onset is associated with a more severe disease course and greater impairment across a wide range of mental and physical disorders and is a useful prognostic marker.Reference Cleynen, Boucher, Jostins, Schumm, Zeissig and Ahmad4–Reference Rhebergen, Lamers, Spijker, De Graaf, Beekman and Penninx7 However, pathophysiological processes leading to a disorder are thought to begin long before the first symptoms appear.Reference Howes, Lim, Theologos, Yung, Goodwin and McGuire8,Reference Wijnands, Kingwell, Zhu, Zhao, Högg and Stadnyk9 Investigating the factors contributing to age and polarity (i.e. either a (hypo)manic or depressive episode) at onset could thus improve our understanding of disease pathophysiology and facilitate development of personalised screening and preventive measures. Accordingly, AAO and polarity at onset (PAO) of bipolar disorder are considered as suitable phenotypes for genetic analyses.

Genome-wide association studies (GWASs) have improved our understanding of the genetic architecture of susceptibility to bipolar disorder; however, the genetic determinants of AAO and PAO remain largely unknown. Evidence suggests that patients with an early AAO carry a stronger genetic loading for bipolar disorder risk.Reference Smoller and Finn10 For example, an earlier parental AAO increases familial risk for bipolar disorder and is one of the strongest predictors of 5-year illness onset in affected offspring.Reference Smoller and Finn10–Reference Hafeman, Merranko, Goldstein, Axelson, Goldstein and Monk12 Previous research has described that a higher genetic risk burden for schizophrenia may be associated with earlier AAO of bipolar disorder,Reference Ruderfer, Ripke, McQuillin, Boocock, Stahl and Pavlides13 but this finding did not replicate.Reference Stahl, Breen, Forstner, McQuillin, Ripke and Trubetskoy14–Reference Kalman, Papiol, Forstner, Heilbronner, Degenhardt and Strohmaier16 Moreover, a recent study did not find an association of bipolar disorder polygenic score (PGS) with AAO.Reference Aas, Bellivier, Bettella, Henry, Gard and Kahn17 Thus far, GWASs for age at bipolar disorder onset have been underpowered,Reference Belmonte Mahon, Pirooznia, Goes, Seifuddin, Steele and Lee18,Reference Jamain, Cichon, Etain, Mühleisen, Georgi and Zidane19 and a study of 8610 patients found no significant evidence for a heritable component contributing to onset age.Reference Ruderfer, Ripke, McQuillin, Boocock, Stahl and Pavlides13 The PAO was shown to cluster in families,Reference Kassem, Lopez, Hedeker, Steele and Zandi20 but the genetic architecture of PAO has not yet been investigated.

Aims

To fill these knowledge gaps, we performed comprehensive analyses of AAO and PAO of bipolar disorder in the largest sample studied to date by (a) examining phenotype definitions and associations, (b) investigating whether the genetic load for neuropsychiatric disorders and traits contributes to AAO and PAO of bipolar disorder, and (c) conducting systematic GWASs.

Method

References to published methods are listed in Supplementary Note 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2021.102.

Study samples

Participants with a bipolar disorder diagnosis, available genetic data and AAO information were selected from independent data-sets, including those previously submitted to the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (PGC) Bipolar Disorder Working GroupReference Ruderfer, Ripke, McQuillin, Boocock, Stahl and Pavlides13 and the International Consortium on Lithium Genetics (ConLiGen).Reference Schulze, Alda, Adli, Akula, Ardau and Bui21 These consortia aggregate genetic data from many cohorts worldwide. Our analyses comprised 34 cohorts with 12 977 patients with bipolar disorder who have European ancestry from Europe, North America and Australia. For a description of sample ascertainment, see the Supplementary Material.

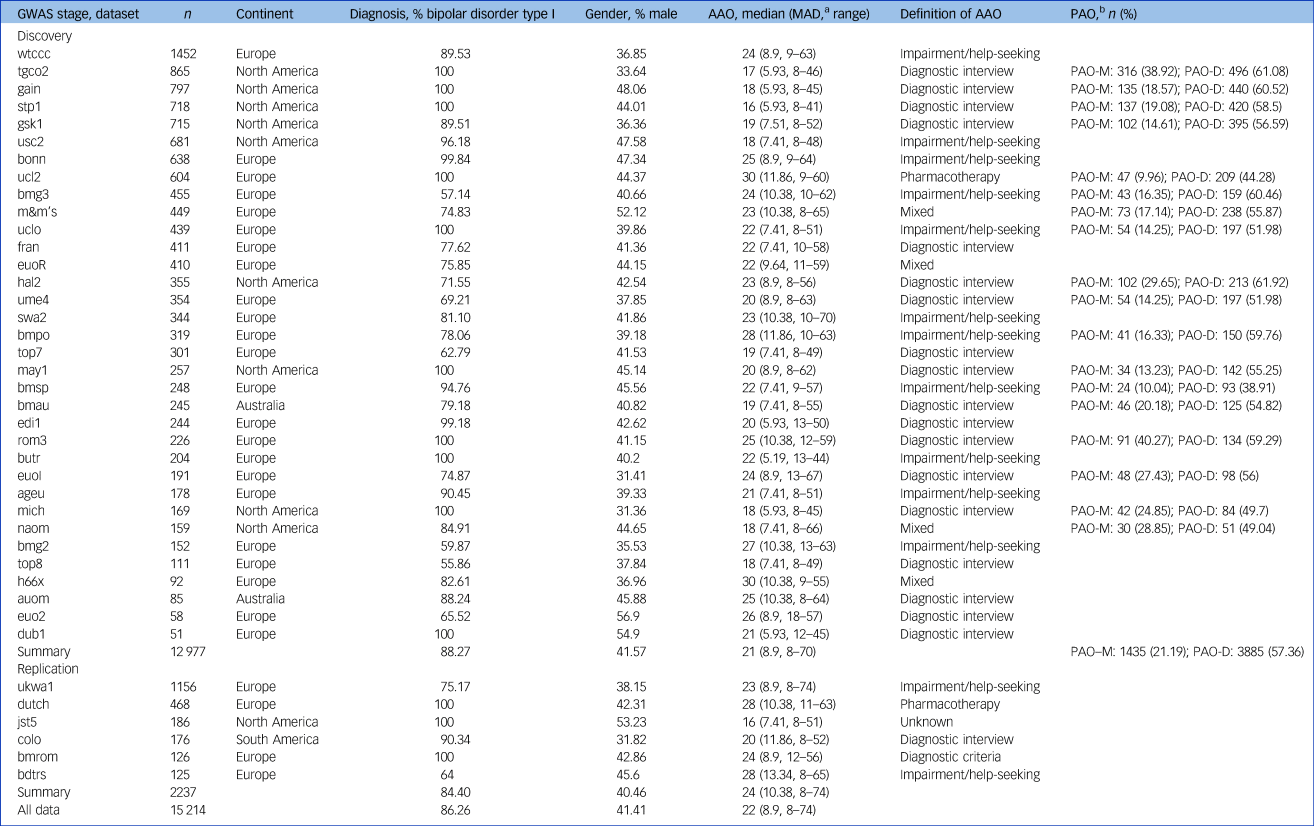

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All procedures involving human patients were approved by the local ethics committees, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients. For details on the data-sets, including phenotype definitions and distributions, see Table 1, Fig. 1, and Supplementary Table S1.

Table 1 Sample characteristics of data-sets used in genetic analyses

GWAS, genome-wide association study; AAO, age at onset; MAD, median absolute deviation, PAO, polarity at onset; PAO-M, mania/hypomania before depression; PAO-D, depression before mania/hypomania.

a. We calculated the median absolute deviation using 1.4826 as constant.

b. We defined three categories of polarity at onset: PAO-M, mania/hypomania before depression; PAO-D, depression before mania/hypomania; and PAO-X, mixed. PAO was not available for all patients. The table presents the PAO-M and PAO-D subgroups and their percentage within the individual cohorts.

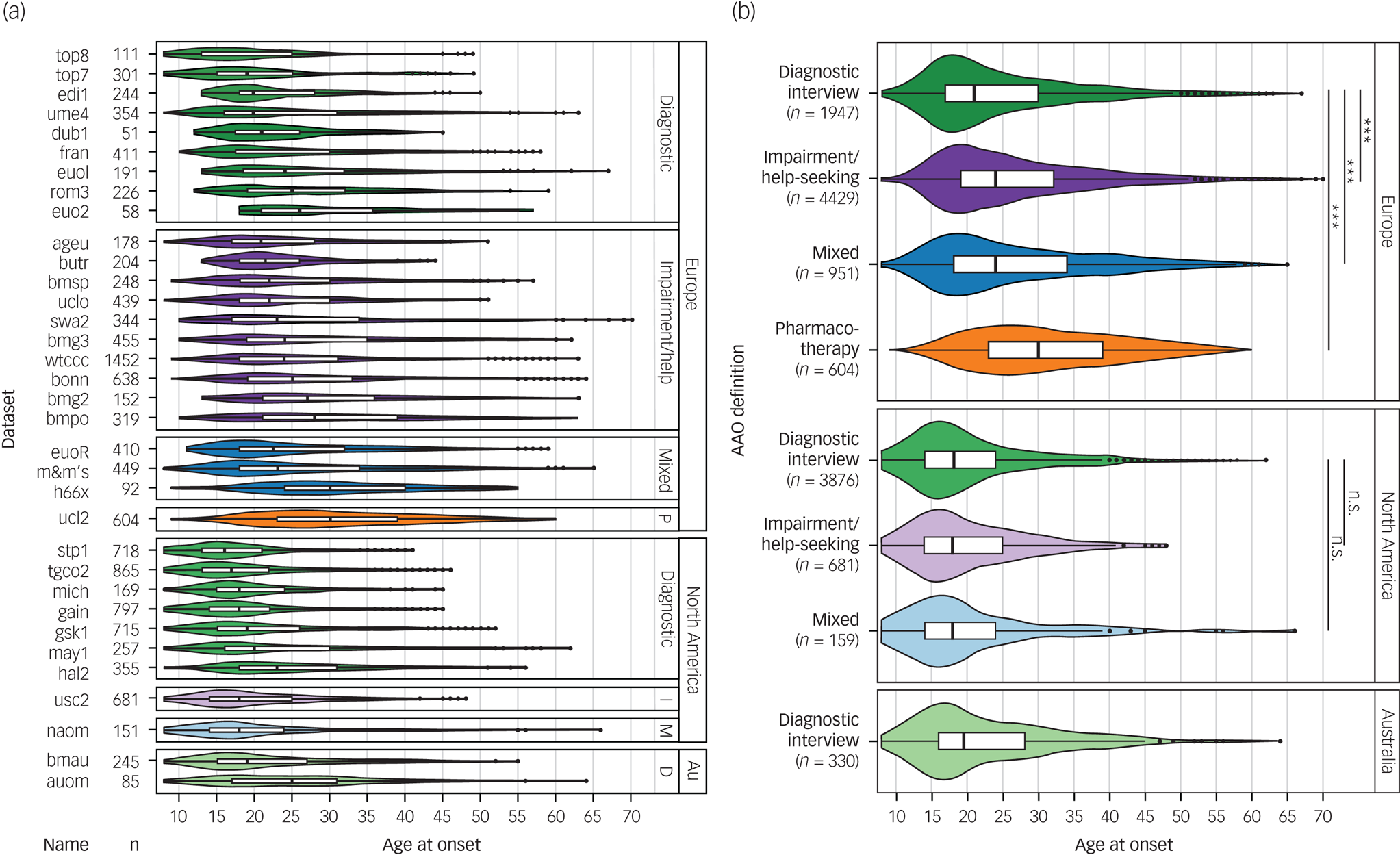

Fig. 1 Differences between phenotype definitions and continents across the 34 data-sets used for discovery-stage genetic analyses.

(a) The various data-sets used four different definitions for age at onset: diagnostic interview, impairment/help-seeking, pharmacotherapy and mixed. (b) The untransformed age at onset differed significantly between cohorts, depending on the phenotype definition used and the continent of origin.

Au, Australia; Diagnostic, diagnostic interview; D, diagnostic interview; I, impairment/help-seeking; M, mixed; P, pharmacotherapy. n.s., not significant; P > 0.05; *** P < 0.001.

Definition of AAO

The definition of age at bipolar disorder onset differed by cohort. To enhance cross-cohort comparability, we grouped the definitions into four broad categories as follows (Supplementary Table S1).

(a) Diagnostic interview: age at which the patient first experienced a (hypo)manic, mixed or major depressive episode according to a standardised diagnostic interview.

(b) Impairment/help-seeking: age at which symptoms began to cause subjective distress or impaired functioning or at which the patient first sought psychiatric treatment.

(c) Pharmacotherapy: age at first administration of medication.

(d) Mixed: a combination of the above-mentioned definitions.

Across definitions, participants younger than 8 years at onset were excluded (n = 279) because of the uncertainty about the reliability of retrospective recall of early childhood onset. The distribution of AAO was highly skewed and differed considerably between the cohorts (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Therefore, we transformed AAO in each cohort by rank-based inverse-normal transformation and used this normalised variable as the primary dependent variable in all genetic analyses. To facilitate interpretability of effect sizes, we also report results of the corresponding untransformed AAO.

Definition of PAO

For each cohort, PAO was defined by comparing the age at the first (hypo)manic and first depressive episode or using the polarity variable provided by the cohort. Specifically, patients were divided into three subgroups:

(a) (hypo)mania before depression (PAO-M);

(b) depression before (hypo)mania (PAO-D); and

(c) mixed (PAO-X).

The third category included patients with mixed episodes and those with a first (hypo)manic and depressive episode within the same year (Table 1). In the primary analysis, we combined patients with (hypo)mania and mixed onset and assigned this as the reference category. In secondary analyses, we excluded the patients in the mixed group.

Phenotypic disease characteristics

We performed phenotypic analyses of disease onset in patients with bipolar disorder type I from three cohorts: the Dutch Bipolar cohort (n = 1313)Reference Van Bergen, Verkooijen, Vreeker, Abramovic, Hillegers and Spijker22 and the German PsyCourseReference Budde, Anderson-Schmidt, Gade, Reich-Erkelenz, Adorjan and Kalman23 and FOR2107Reference Kircher, Wöhr, Nenadic, Schwarting, Schratt and Alferink24 cohorts, which were analysed jointly (n = 346). We analysed the following disease characteristics, which were previously reported as being associated with disease onset and were assessed in a similar way across cohorts: lifetime delusions, lifetime hallucinations, history of suicide attempt, suicidal ideation, current smoking, educational attainment, living together with a partner, and frequency of manic and depressive episodes per year. For more detailed information, see the Supplementary Note 2 and Supplementary Table S9.

Quality control and imputation of genotype data

The cohorts were genotyped according to local protocols. Individual genotype data of all discovery-stage cohorts were processed with the PGC Rapid Imputation and Computational Pipeline for GWAS (RICOPILI) with the default parameters for standardised quality control, imputation and analysis. Before imputation, filters for the removal of variants included non-autosomal chromosomes, missingness ≥0.02, and a Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium test P < 1 × 10−10. Individuals were removed if they showed a genotyping rate ≤0.98, absolute deviation in autosomal heterozygosity of Fhet ≥0.2, or a deviation >4 s.d.s from the mean in any of the first eight ancestry components within each cohort. From genetic duplicates and relatives (pi-hat >0.2) across all samples, only the individual with more complete phenotypic information on AAO and PAO, gender and diagnosis was retained. Imputation was performed by IMPUTE2 with the Haplotype Reference Consortium reference panel.

PGS

We calculated PGS based on prior GWAS of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism spectrum disorder (ASD), bipolar disorder, educational attainment (measured as ‘years in education’), major depression (MD), and schizophrenia (see Supplementary Table S3, which includes references). PGS weights were estimated with PRS-CS(see Supplement), with six scores per GWAS (with φ = 1 × 10−1, 1 × 10−2, 1 × 10−3, 1 × 10−4, 1 × 10−5, and 1 × 10−6). We tested the associations of the PGS with the AAO and PAO by linear and logistic regressions, respectively. Gender, bipolar disorder subtype and the first eight ancestry components were included as covariates. The significance threshold was Bonferroni-corrected for 96 tests (α = 0.05/(6 φ thresholds × 8 traits × 2 phenotypes) = 5.2 × 10−4).

GWASs

We performed a discovery GWAS on the 34 cohorts (n = 12 977) and replication analyses in six additional cohorts with n = 2237 patients with bipolar disorder. As a first step, we conducted individual GWAS for each cohort with 40 or more patients using the RICOPILI workflow, using the same covariates as in the PGS analyses. Sample sizes are provided in Supplementary Tables S2 and S7. The resulting GWAS did not show an inflation of test statistics for any of the cohorts, indicating limited population stratification (Supplementary Table S2). Next, we performed a fixed-effects meta-analysis using METAL, combining the cohort-specific GWASs. For the meta-analysis summary statistics, we applied the following variant-level post-quality control parameters: imputation INFO score ≥0.9, minor allele frequency (MAF) ≥0.05, and successfully imputed/genotyped in more than half of the cohorts.

The primary analyses were AAO (normalised, analysed by linear regression) and PAO (analysed by logistic regression). Secondary analyses included GWASs stratified by AAO definition and continent of origin.

We estimated the power to replicate our initial genome-wide significant finding from the discovery GWAS based on the regression coefficients using the pwr package in R. Assuming the same effect size and MAF (beta 0.075, allele frequency 0.32) and a standardised phenotype, we had 76% power to detect the effect in our sample size of 2237 at an alpha level of 0.1. For comparison, we had 57% power to detect the effect in our discovery sample, using the more stringent genome-wide significance cut-off.

Heritability analyses

Next, we assessed the overall variance in AAO and PAO explained by genotyped variants (so-called single-nucleotide variant (SNV)-based heritability, h2SNV). For the only individual cohort with more than 1000 samples, we estimated h2SNV with GCTA GREML. In this case, we validated the robustness of the h2SNV estimate with the mean of 1000 × resampling of 95% of the sample. To estimate the overall heritability of the meta-analysis summary statistics we estimated h2SNV by linkage disequilibrium score regression, for each GWAS with sample size >3000. The 95% CIs were constrained to a minimum of 0 and a maximum of 1.

Results

Heterogeneity of AAO and PAO across cohorts

Among the four definitions of AAO across the 34 cohorts, impairment/help-seeking was the most common in Europe and diagnostic interview the most common in North America (Table 1, Fig. 1). Across all cohorts, the median AAO was 21 years (range of medians: 16–30 years; Fig. 1). However, substantial differences in the AAO were observed between subgroups: first, the median untransformed AAO was lower in bipolar disorder type I than in type II (type I, 21 years; type II, 22 years; Kruskal-Wallis test P = 1.8 × 10−4; Supplementary Table S6).

Second, the AAO was lower when determined by diagnostic interview compared with other phenotype definitions (diagnostic interview, 19 years; impairment/help-seeking, 23 years; pharmacotherapy, 30 years; mixed, 22 years; P = 2.96 × 10−191). Third, the age was lower in North America compared with Europe (Europe, 24 years; North America, 18 years; and Australia, 19.5 years; P = 2.0 × 10−263). These differences across continents remained significant when including onset definitions and bipolar disorder subtype in a multivariable regression model, indicating that they are likely partially independent from the assessment strategy (Supplementary Table S6).

The majority of patients reported a depression-first PAO. Patients with depression-first were less frequent in the impairment/help-seeking than in the diagnostic interview category (55% and 60%, respectively; P = 4.5 × 10−4, Supplementary Fig. S1), but their proportions were similar between Europe and North America (57% and 59%, respectively; P = 0.17 test of proportion).

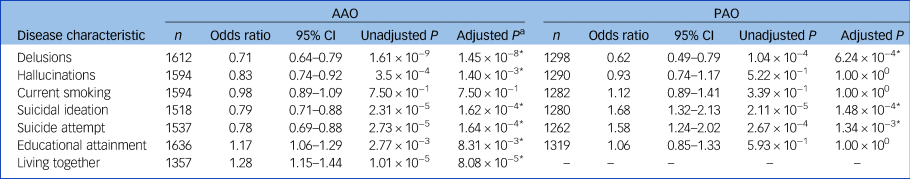

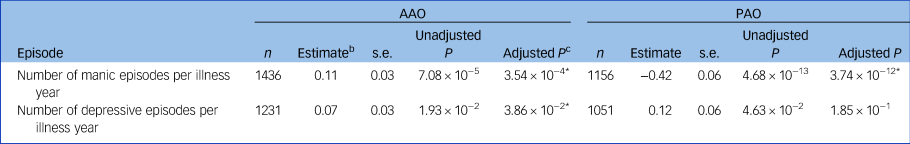

Analyses of disease characteristics

In a meta-analysis of the Dutch and German samples, earlier AAO was significantly associated with a higher probability of lifetime delusions, hallucinations, suicide attempts, suicidal ideation, lower educational attainment and not living together (Table 2, Supplementary Tables S4 and S5). A later AAO was positively significantly correlated with a higher number of manic and depressive episodes per year (see Tables 3, and the Supplementary Note 2). Moreover, a (hypo)manic onset was significantly associated with a greater likelihood of delusions and more manic episodes per year, whereas a depressive onset was associated with a higher probability of suicidal ideation and lifetime suicide attempts.

Table 2 The association of age and polarity at onset with disease characteristics in two European bipolar disorder cohorts

AAO, age at onset; PAO, polarity at onset; n, total number of participants from the Dutch and German cohorts.

* P < 0.05

a. After Bonferroni–Holm correction.

Table 3 The association of age and polarity at onset with manic and depressive episodes in two European bipolar disorder cohortsa

AAO, age at onset; PAO, polarity at onset; n, total number of participants from the Dutch and German cohorts.

* P < 0.05

a. The number of manic/depressive episodes was divided by (years of illness) + 1. For secondary analyses of the number of episodes not corrected for the years of illness, see the Supplementary Note 2.

b. Unstandardised beta coefficient.

c. After Bonferroni–Holm correction.

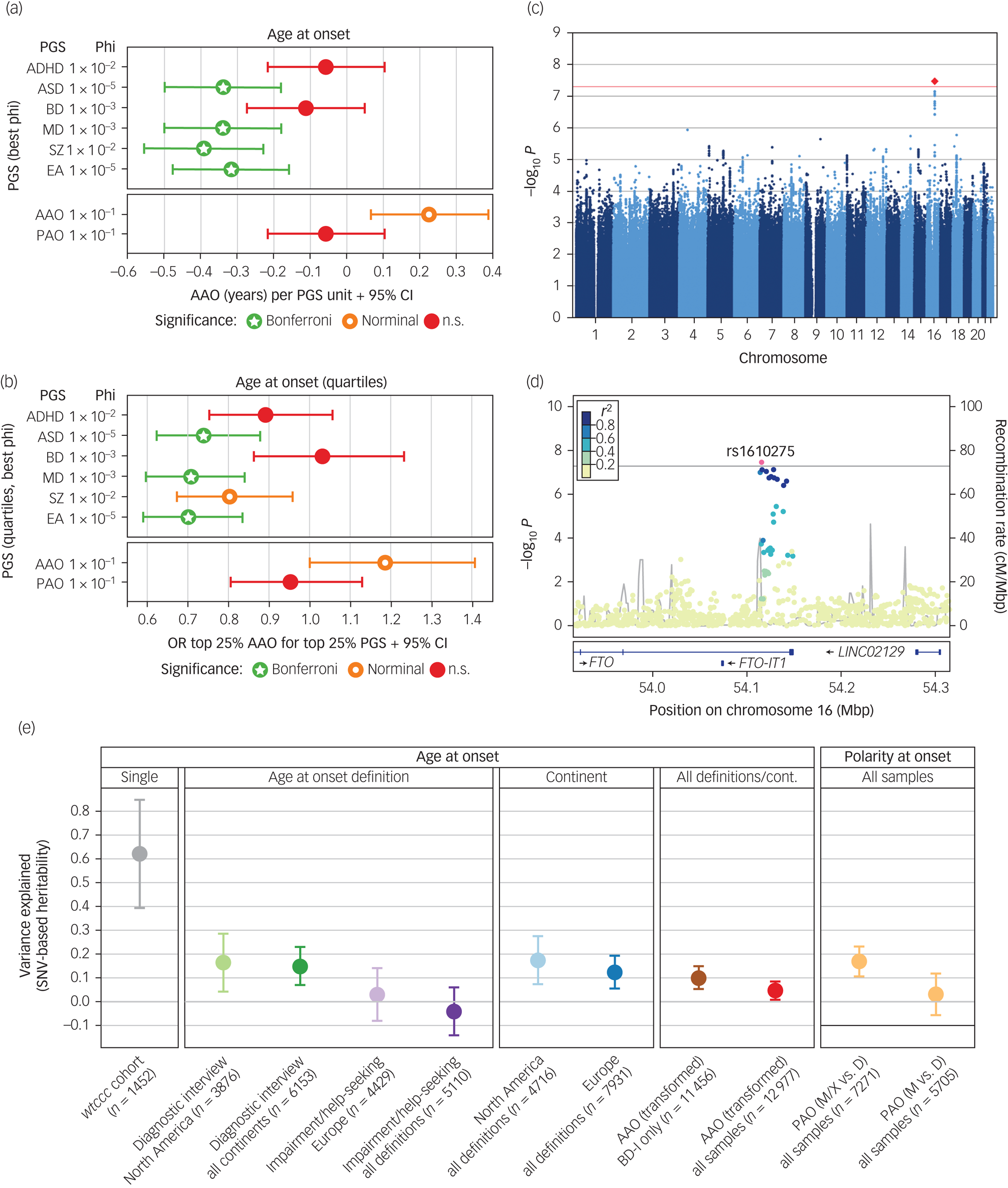

Associations of PGSs with AAO and PAO

Next, we conducted analyses to evaluate whether the genetic liability for five psychiatric disorders and educational attainment were associated with the age at disease onset (Fig. 2(a) and (b) and Supplementary Table S8). After correcting for 96 tests, higher PGSs for ASD (β = −0.34 years per 1 s.d. increase in PGS, s.e. = 0.08, P = 9.85 × 10−6), major depression (β = −0.34, s.e. = 0.08, P = 1.40 × 10−6), schizophrenia (β = −0.39, s.e. = 0.08, P = 2.91 × 10−6) and educational attainment (β = −0.31, s.e. = 0.08, P = 5.58 × 10−5) were significantly associated with an earlier age at bipolar disorder onset. This was not the case for ADHD or bipolar disorder PGS. No PGS was significantly associated with PAO (Supplementary Fig. S4, Supplementary Table S8).

Fig. 2 Results from the genome-wide association study (GWAS), polygenic score (PGS) analyses, and heritability analyses.

(a) and (b) Results from analyses of PGS. For detailed results, see Supplementary Table S8. Significance levels: n.s., not significant, P > 0.05; nominal: P < 0.05; Bonferroni, below the Bonferroni-corrected significance threshold corrected for 96 tests (P < 5.2 × 10−4). (a) Associations of PGSs with the AAO. For interpretability, the plot shows the untransformed AAO. Significance levels are based on the analyses of the AAO after rank-based inverse-normal transformation (which was performed because the distribution of AAO was highly skewed and differed greatly across the study cohorts). (b) Associations of the top versus bottom AAO quartiles with the top versus bottom PGS quartiles. A higher odds ratio (OR) indicates an association with higher AAO. (c) Manhattan plot of the discovery-stage AAO GWAS. (d) Locus-specific Manhattan plot of the top-associated AAO variant. (e) Estimation of the variance in different phenotype definitions explained by genotyped single-nucleotide variants (SNV) (h2SNV). For the cohort wtccc, we directly estimated h2SNV from genotype data in GCTA GREML; we estimated all other heritabilities from GWAS summary statistics using LDSC. The plot shows h2SNV estimates and s.e.

ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; BD, bipolar disorder; cM, centi Morgan. Mbp, mega base pairs; MD, major depression; EA, educational attainment; SNV, single-nucleotide variant; cont, continent; disorder type I; PAO, polarity at onset; PAO-M, mania/hypomania before depression; PAO-D, depression before mania/hypomania; PAO-X, mixed; SZ, schizophrenia.

GWASs

Next, we attempted to identify individual genetic loci associated with the AAO or PAO. In our discovery GWAS using 34 cohorts, one locus was significantly associated with AAO (rs1610275 on chromosome 16; minor allele G frequency = 0.319, β = 0.075 (s.e. = 0.014), P = 3.39 × 10−8, Fig. 2(c), Supplementary Table S7, Supplementary Fig. S2). This SNV mapped to an intron of the brain-expressed gene FTO (alpha-ketoglutarate dependent dioxygenase, Fig. 2(d)). However, this association was not replicated in an independent sample of six cohorts (Supplementary Table S7, Supplementary Fig. S2). In the replication sample (n = 2237), we had 76% power to replicate this SNV at a P-value threshold of 0.1. The GWAS of PAO did not yield any genome-wide significant findings, in either primary (PAO-M/-X versus PAO-D) or secondary (PAO-M versus PAO-D) analyses (Supplementary Fig. S3).

We also calculated PGSs for AAO and PAO using leave-one-out summary statistics from these GWASs. The AAO PGS was nominally significantly associated with AAO (β = 0.23 years, s.e. = 0.08, P = 0.0087, φ = 0.1, Fig. 2(a) and 2(b)) for five of six tested φ parameters but did not withstand correction for multiple testing (Supplementary Table S8). The PAO PGS was not associated with the PAO (Supplementary Fig. S4).

SNV-based heritability of the investigated phenotypes

We estimated the SNV-based heritability h2SNV directly from genotype data using GCTA in the only cohort large enough for this analysis, wtccc. For the AAO, the h2SNV in wtccc was estimated at 0.63 (P = 0.0026) (Fig. 2(e)). We evaluated the robustness of this estimate by resampling (mean h2SNV = 0.62, resampling 95% CI 0.15–1.00).

We next estimated h2SNV by linkage disequilibrium score regression (LDSC) from the GWAS summary statistics generated in the present study (Fig. 2(e)). We observed that the heritability decreased when cohorts, phenotype definitions and continents were combined (for example ‘diagnostic interview’ in North America: AAO h2SNV = 0.16, 95% CI 0–0.40, ‘impairment/help-seeking’ in Europe: h2SNV = 0.03, 95% CI 0–0.25, all combined h2SNV = 0.05, 95% CI 0–0.12). As a result of the insufficient sample size, we could not estimate the h2SNV of impairment/help-seeking in North America and diagnostic interview in Europe. For depression versus (hypo)manic and mixed PAO, h2SNV was 0.17 (95% CI 0.05–0.29) on the observed scale.

Discussion

In our study of bipolar disorder disease onset, we first evaluated the association between AAO or PAO with several clinical indicators of severity in a sample of 1659 patients. We showed that an earlier onset is associated with increased severity, demonstrating and replicating the clinical relevance of these phenotypes. Next, we performed genetic analyses including 12 977 patients from 34 cohorts. Here, we demonstrated that higher genetic risk for ASD, major depression, schizophrenia and educational attainment is associated with an earlier AAO, providing evidence that the age at bipolar disorder onset is influenced by a broad liability for psychiatric illness.

Third, we performed GWAS to identify genetic variants associated with the AAO and PAO, which did not yield any replicated associations. Fourth, we outlined the extent to which age (and, partly, polarity) at onset varies across cohorts, depending both on the continent of recruitment and on the diagnostic instrument used to determine the AAO.

Finally, we showed that this substantial phenotypic heterogeneity affects the heritability of the phenotype, which decreased when multiple cohorts with different diagnostic instruments were combined. This analysis emphasises how genetic analyses are hampered by phenotypic heterogeneity.

Illness onset is associated with disease course

In a first set of analyses, we confirmed the clinical relevance of disease onset phenotypes in bipolar disorder. Age at bipolar disorder onset was associated with important illness severity indicators, such as suicidality, psychotic symptoms and lower educational attainment, thereby replicating findings of previous studies.Reference Van Bergen, Verkooijen, Vreeker, Abramovic, Hillegers and Spijker22,Reference Perlis, Miyahara, Marangell, Wisniewski, Ostacher and DelBello25 Furthermore, patients with a depressive bipolar disorder onset had an increased reported lifetime suicidality, whereas those with a (hypo)manic onset were more likely to experience delusions and more manic episodes per illness year. Contrary to previous evidence in a US (but not in a French) sample, we observed that an earlier onset was associated with fewer episodes per illness year.Reference Etain, Lajnef, Bellivier, Mathieu, Raust and Cochet26 Of note, when not normalising for the illness duration, the AAO was, as expected, positively correlated with the number of episodes (see Supplementary Note 2).

Increased genetic scores for neuropsychiatric phenotypes predict an earlier illness onset

Higher PGSs for schizophrenia, major depression, ASD and educational attainment were significantly associated with a lower AAO, and none of the tested PGSs were significantly associated with PAO. Our findings support the hypothesis that a general liability for psychiatric disorders influences an earlier age of onset in bipolar disorder. Alternatively, an earlier onset may also reflect the broader phenotypic spectrum sometimes captured in early-onset bipolar disorder. Unexpectedly, and in contrast to several other disorders (for example multiple sclerosis), where the strongest genetic risk factors for disease liability are also the most important genetic factors associated with an earlier disease onset,Reference Naj, Jun, Reitz, Kunkle, Perry and Park6,Reference Andlauer, Buck, Antony, Bayas, Bechmann and Berthele27 we did not find a significant association between bipolar disorder PGS and the age at bipolar disorder onset. Statistical power may have influenced this result, as the sample sizes of both the schizophrenia and major depression GWASs were larger than that of the bipolar disorder GWAS, improving the predictive ability of these PGSs compared with the bipolar disorder PGS.

The described significant relationship of higher educational attainment PGS with an earlier AAO may seem counterintuitive. However, several studies described a significant association, genetic correlation and causal relationship between a higher educational attainment and bipolar disorder risk.Reference Mullins, Forstner, O'Connell, Coombes, Coleman and Qiao28,Reference Vreeker, Boks, Abramovic, Verkooijen, Van Bergen and Hillegers29 Our findings demonstrate that a high educational attainment PGS is not only a risk factor for bipolar disorder but also associated with an earlier onset of the disorder.

Lack of replication of the GWAS finding

We have conducted two GWASs to identify individual loci influencing the age and polarity at bipolar disorder onset, possibly independently of affecting lifetime disorder risk. Our discovery GWAS prioritised a genome-wide significant locus associated with the AAO. However, the lack of replication suggests that this finding may have been false-positive. This failure to replicate could have been because of insufficient statistical power in the replication sample, as our power analysis did not account for the likely phenotypic and genetic heterogeneity across cohorts and may thus have underestimated the necessary sample size. Importantly, the replication sample was more ethnically diverse than the discovery sample, which reduced the statistical power. The PAO GWAS, with its lower sample size and dichotomous phenotype, did not identify any genome-wide significant locus.

We also calculated an AAO PGS using our GWAS and tested it on our sample. Although the effect size of this PGS on the AAO was substantial (0.23 years per unit change in the PGS), the association was only nominally significant.

The heterogeneity of phenotype definitions

A striking finding of our study was the systematic difference in the AAO distribution across cohorts, continents and assessment strategies. Although the assessment strategies varied considerably by continent, with diagnostic interview being mainly used in North America and impairment/help-seeking in Europe, we showed that the continent-level differences were partially independent from the AAO assessment strategy and that both factors contributed significantly to the heterogeneity (Supplementary Table S6). However, variations in the demographic structure of analysed populations may have biased the assessed AAO of bipolar disorder, contributing to the observed differences. Although prior research has identified AAO differences across continents (for example the incidence of early-onset bipolar disorder is higher in the USA than in Europe)Reference Post, Luckenbaugh, Leverich, Altshuler, Frye and Suppes30 this study is the first to systematically assess this heterogeneity across many cohorts with different ascertainment strategies.

For the polarity at disease onset, the relative proportion of patients reporting a depressive index episode did not differ across continents but across instruments. A (hypo)manic onset was more common if the onset was based on an impairment/help-seeking instead of diagnostic interview phenotype definition.

Phenotypic heterogeneity affects genetic analyses

Interestingly, the systematic differences in AAO phenotypes across cohorts are reflected in heritability estimates: we observed the highest SNV-based heritability h2SNV when onset was established by diagnostic interview and the lowest when it was captured with more health system-specific and subjective measurements, such as item 4 of the Operational Criteria Checklist for Psychotic Illness (impairment/help-seeking). Moreover, h2SNV estimates approached zero when all samples were combined in our primary analysis (h2SNV = 0.05; 95% CI 0–0.12), underscoring the strong impact of phenotypic heterogeneity. For PAO-M/-X versus PAO-D, we observed significant h2SNV estimates, demonstrating that genetic factors contribute to the polarity at bipolar disorder onset.

Thus, we not only showed systematic heterogeneity in a clinically relevant psychiatric phenotype across cohorts but also provided direct evidence for how this heterogeneity can hamper genetic studies. Similarly, a recent investigation demonstrated that the phenotyping method (for example diagnostic interview versus self-report) significantly influenced heritability estimates, GWAS results and PGS performance in analyses of major depression susceptibility, with broader phenotype definitions resulting in lower heritability estimates.Reference Cai, Revez, Adams, Andlauer, Breen and Byrne31 These results indicate that although increasing samples sizes generally improves the power to detect significant associations, larger samples are no silver bullet: careful phenotype harmonisation and uniform recruitment strategies are likely at least as important.

Limitations

In addition to diverse phenotype definitions originating from different ascertainment methods, as described above, several factors may have limited the cross-cohort comparability of the AAO and PAO. These factors include differences in the definition and ascertainment of the age at bipolar disorder onset and in how bipolar disorder was diagnosed across cohorts and continents. Such differences can lead to bias, affecting genetic analyses. For example, as patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder type II show, on average, later ages at onset than patients with bipolar disorder type I,Reference Manchia, Maina, Carpiniello, Pinna, Steardo and D'Ambrosio32 differing proportions of bipolar disorder subtypes across cohorts may have an impact on AAO analyses. Therefore, we included the bipolar disorder subtype as a covariate in our genetic analyses to control for this confounder. Still, this cross-cohort heterogeneity has likely reduced our statistical power.

Given that, for all included cohorts, the disease onset phenotypes were assessed retrospectively, measurement errors associated with interrater reliabilities and recall bias may have occurred across cohorts. For example, hypomania was likely underreported, potentially biasing the PAO towards depression. Notably, such potential issues are not specific to the present study but may affect all retrospective analyses of psychiatric phenotypes. Nevertheless, differences in the diagnosis of bipolar disorder and the ascertained phenotypes between cohorts might have exacerbated these problems. Therefore, future studies should focus on compiling clinically more homogeneous, phenotypically better-harmonised data-sets instead of only assembling the largest possible sample.

Furthermore, the rank-based inverse normal transformation of the AAO phenotype may have affected the GWAS and heritability analyses. We conducted this transformation because, first, the original AAO distribution was highly skewed and thus not suitable for linear regression and, second, the AAO differed significantly between cohorts, which could have biased the meta-analysis. However, by transforming the data, only the rank and not the absolute differences in onset between patients was maintained, reducing the interpretability of the phenotype and the genetic effects.

We performed both SNV-level and polygenic score associations using a structured meta-analysis, which mitigates some of the noise introduced by phenotypic heterogeneity. However, we were unable to account for differences in the underlying genetic aetiology of the phenotypes across cohorts. As described above, phenotypic heterogeneity is an important limitation of our study and should be considered in future phenotype and genetic analyses. Our results need to be interpreted in light of these limitations.

Implications

Phenotypes of bipolar disorder onset are clinically important trait measures contributing to the well-known clinical and biological heterogeneity of this severe psychiatric disorder. Genetic analysis of AAO and PAO may lead to a better understanding of the biological risk factors underlying mental illness and support clinical assessment and prediction. Our study provides evidence of a genetic contribution to age and polarity at bipolar disorder onset but also demonstrates the need for systematic harmonisation of clinical data on bipolar disorder onset in future studies.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2021.102

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jacquie Klesing, Board-certified Editor in the Life Sciences (ELS), for editing assistance with the manuscript. BOMA-Australia sample: we thank Gin Mahli, Colleen Loo, and Micheal Breaskpear for their contribution to clinical assessments of a subset of patients and also Andrew Frankland for his work in collating clinical record data. WTCCC sample: this study makes use of data generated by the Wellcome Trust Case-Control Consortium. A full list of the investigators who contributed to the generation of the data is available from www.wtccc.org.uk. French sample: we thank the psychiatrists and psychologists who participated in the clinical assessment of patients in France (C. Henry, S. Gard, J.P. Kahn, L. Zanouy, R.F. Cohen and O. Wajsbrot-Elgrabli) and thank the patients for their participation.

Author contributions

Concept and design: Janos L. Kalman, Loes M. Olde Loohuis, Annabel Vreeker, Till F.M. Andlauer, Thomas G. Schulze and Roel A. Ophoff. Analysis and interpretation of data: Janos L. Kalman, Loes M. Olde Loohuis, Annabel Vreeker and Till F.M. Andlauer. Drafting of the manuscript: Janos L. Kalman, Loes M. Olde Loohuis, Annabel Vreeker and Till F.M. Andlauer. Supervision, and critical revision of the manuscript: Thomas G. Schulze, Roel A. Ophoff, Francis J. McMahon, Jordan W. Smoller and Martin Alda. All other authors provided data, contributed ideas and suggestions for analyses, interpreted results and revised the final manuscript.

Funding

The funding details can be found in the Supplementary File 1.

Declaration of interest

Amare T. Azmeraw: has received 2020–2022 NARSAD Young Investigator Grant from the Brain & Behaviour Research Foundation. Ole A. Andreassen: speaker's honorarium Sunovion, Lundbeck. Consultant HealthLytix. Bernhard Baune: Honoraria: Lundbeck, Janssen, LivaNova, Servier. Carrie Bearden: Novartis Scientific Advisory Board. Clark Scott: Honoraria and Investigator-initiated project funding from Jannsen-Cilag Australia, Lundbeck-Otsuka Australia. J. Raymond DePaulo: owns stock in CVS Health; JRD was unpaid consultant for Myriad Neuroscience 2017 & 2019. Michael C. O´Donovan: research unrelated to this manuscript supported by a collaborative research grant from Takeda Pharmaceuticals. Bruno Etain: honoraria for Sanofi. Mark A. Frye: grant Support Assurex Health, Mayo Foundation, Medibio Consultant (Mayo) Actify Neurotherapies, Allergan, Intra-Cellular Therapies, Inc., Janssen, Myriad, Neuralstem Inc., Sanofi, Takeda, Teva Pharmaceuticals. Per Hoffmann: employee of Life&Brain GmbH, Member of the Scientific Advisory Board of HMG Systems Engeneering GmbH. Mikael Landen: Speaker's honoraria Lundbeck pharmaceuticals. Andrew M McIntosh: research funding from The Sackler Trust, speaker fees from Illumina and Janssen. Philip B. Mitchell: remuneration for lectures in China on bipolar disorder research by Sanofi (Hangzhou). John Nurnberger: investigator for Janssen. Benjamin M. Neale: is a member of the scientific advisory board at Deep Genomics and RBNC Therapeutics. A consultant for Camp4 Therapeutics, Takeda Pharmaceutical and Biogen. Andreas Reif: apeaker's honoraria / Advisory boards: Janssen, Shire/Takeda, Medice, SAGE and Servier. Eli Stahl: now employed by the Regeneron Genetics Center. Kato Tadafumi: honoraria: Kyowa Hakko Kirin Co., Ltd., Eli Lilly Japan K.K., Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., GlaxoSmithKline K.K., Taisho Pharma Co., Ltd., Taisho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Taisho Toyama Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma Co., Ltd., Meiji Seika Pharma Co., Ltd., Pfizer Japan Inc., Mochida Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Shionogi & Co., Ltd., Janssen Pharmaceutical K.K., Janssen Asia Pacific, Yoshitomiyakuhin, Astellas Pharma Inc., Nippon, Boehringer Ingelheim Co. Ltd., MSD K.K., Kyowa Pharmaceutical Industry Co., Ltd., Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, Eisai Co., Ltd. Grants: Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma Co., Ltd., Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Shionogi & Co., Ltd., Eisai Co., Ltd., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation. Thomas G. Schulze: is a member of the editorial board of The British Journal of Psychiatry. He did not take part in the review or decision-making process of this paper. Eduard Vieta: has received grants and served as consultant, advisor or CME speaker for the following entities: AB-Biotics, Abbott, Allergan, Angelini, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Ferrer, Gedeon Richter, Janssen, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Sage, Sanofi-Aventis, Sunovion and Takeda. None of the other authors reported any biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest. ICMJE forms are in the supplementary material, available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/10.1192/bjp.2021.102.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.