Introduction

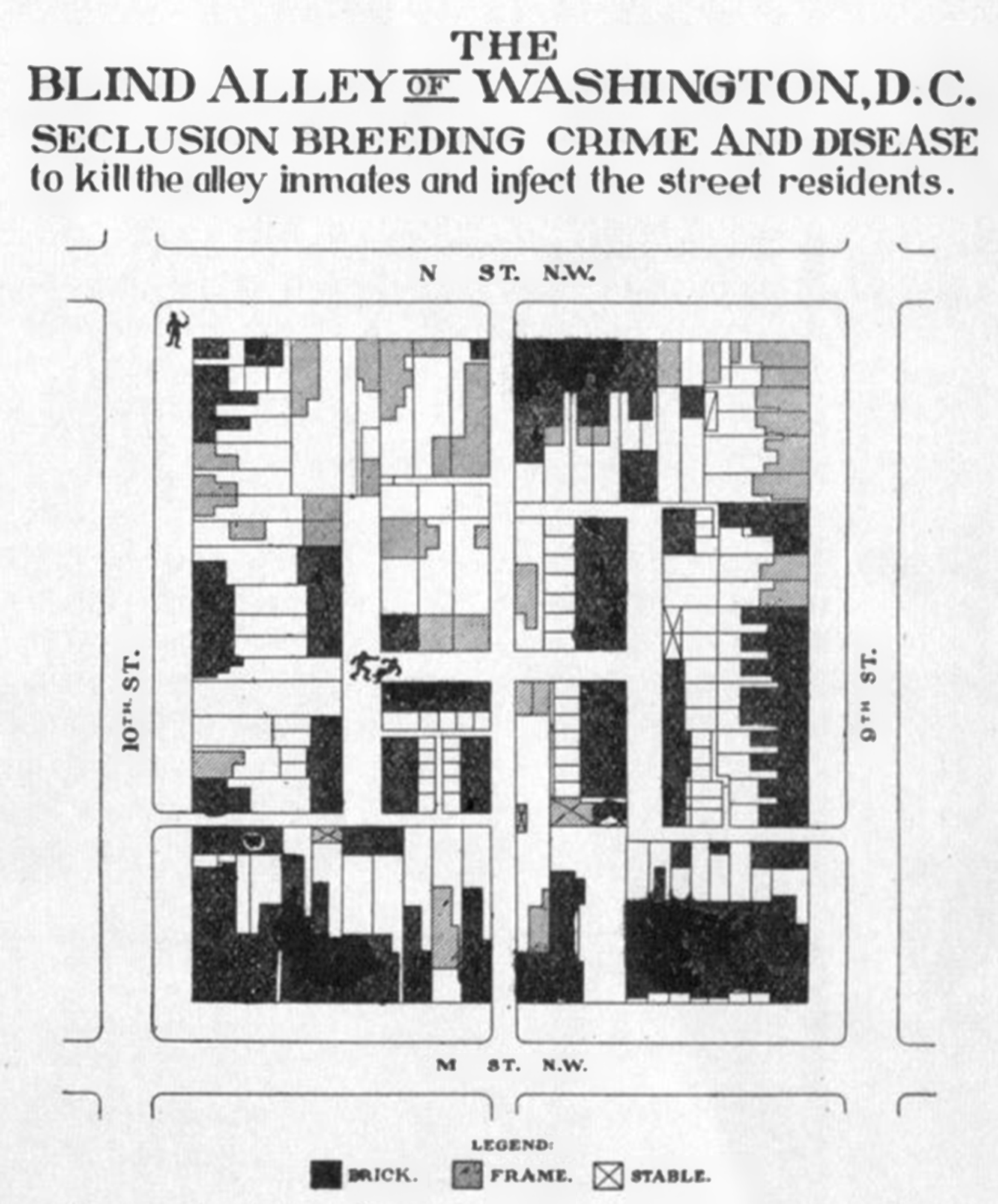

In 1912, the Monday Evening Club, a prominent civic organization aimed at addressing social problems in Washington, D.C. (DC), published a “Directory of the Inhabited Alleys of Washington DC” written by Dr. Thomas Jesse Jones, chairman of its housing committee. The directory offered readers information about the locations of inhabited alleys across the city, decried alley conditions, and discussed ongoing efforts to eliminate alleys. At the time, well over 200 DC alleys were densely inhabited by impoverished Black residents, dispersed throughout the city’s neighborhoods and often in close proximity to white households and institutions; as Jones put it, “they are so widely distributed throughout the city that even the best residential sections are not free from their evil influences.” Elite actors of reform – such as public health agencies, civic and professional associations, and charitable organizations – were engaged in an aggressive campaign to eradicate alleys, which ultimately contributed to the disappearance of all but a handful (Borchert Reference Borchert1971). In particular, reformers cited alleys’ perceived unsanitary conditions and high rates of disease, and frequently highlighted the potential for alley conditions to affect the rest of the city’s population, as contagious disease could easily traverse the short distance to elite homes and institutions. As Jones’ directory (Reference Jones1912) puts it, alleys are characterized by “seclusion breeding crime and disease to kill the alley inmates and infect the street residents” (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Jones, T.J. “Directory of the Inhabited Alleys of Washington D.C.,” Monday Evening Club; 1912.

This paper makes a unique contribution by systematically mapping DC’s alleys in the early 1900s, linking them to population and disease data, and placing the findings in historical context for a critical assessment of the alley reform movement. The Board of Health sections of the 1912–13 and 1913–14 Annual Reports of the Commissioners of the District of Columbia (hereafter, “BOH reports”) offer an unusually rich source of demographic and epidemiological data on alley residents. Historical GIS (HGIS) enables novel spatial visualization of this information through georeferencing the alleys named in the BOH reports and linking them to the associated data. Combining these quantitative and spatial sources with qualitative perspectives from contemporary housing reformers enables new perspectives on segregation, public health, and the racialized nature of housing reform during this period.

Specifically, such mixed-methods research sheds light on the fine-grained patterns of racial residential segregation early in the century, how white residents responded to them, and how these patterns began to transform to neighborhood-level segregation. Recent spatial analysis has documented that, although segregation appears low on the neighborhood level in this time period, on a smaller scale it was already high and rising – and identified that spatial configurations such as the alley played a role (Logan and Bellman Reference Logan and Bellman2016; Grigoryeva and Ruef Reference Grigoryeva and Ruef2015; Logan and Martinez Reference Logan and Martinez2018). However, this largely quantitative research focuses primarily on assessing segregation levels and patterns, and thus, research remains lacking on the lived experience of this form of segregation, in which Black and white residents were in close spatial proximity yet meaningfully separated, and on how it disappeared.

Critical reassessment of historical spatial epidemiology through mixed-methods analysis, revealing racial bias in its interpretation, provides a lens for exploring these aspects of the alley typology. Previous scholarship on alleys accepts or at least leaves unchallenged the reformers’ argument that disease flourished in unsanitary alley conditions and/or that residents bore disproportionately high burdens of disease (Borchert Reference Borchert1982: 183; Gillette Reference Gillette2006; Farrar Reference Farrar2008; Asch and Musgrove Reference Asch and Musgrove2017: 179). However, an analysis of alley-level epidemiological data reveals that this argument was overstated. Infectious disease in alleys was in fact not the terrifying epidemic that reformers portrayed it to be: most alleys had no such deaths, and mortality rates were not much different from those on streets for Black residents. Why then did reformers interpret alley epidemiology in such a dire light? And why did they wage such a determined battle to eliminate “diseased” alleys?

In answering this question, I draw on Black geographies scholarship, which emphasizes the mutually constitutive relationship between race and space (McKittrick Reference McKittrick2011, Reference McKittrick2013; Hawthorne Reference Hawthorne2019; Brand and Miller Reference Brand and Miller2020; Lipsitz Reference Lipsitz2011). Specifically, this scholarship points to how space is not only a container for and reflection of processes with racialized impacts, but also racism and racialization are enacted through space. I argue that the claim that alleys were breeding grounds of disease was not scientific fact but social construction, shaped by reformers’ preconceptions that Black communities were inherently pathological. Further, I contend that the ardor of their campaign was influenced by the pattern of micro-segregation at the scale of the city block, which triggered reformers’ apprehension and anxiety over Black alley communities’ spatial proximity to white Washington – specifically fear of contagion. Shared neighborhoods hardly brought harmonious coexistence; rather, white residents actively urged the displacement of their Black neighbors, contributing to the rise of neighborhood-level segregation.

To examine the underlying principles and beliefs of the alley reform movement and how they informed reformers’ perceptions of alleys, I use the lens of Jones’ work. A white sociologist who held a Ph.D. from Columbia University, he, like many alley reformers, was far removed socially from marginalized Black alley residents. His work as leader of a philanthropic association evinced a paternalistic mission, based on a view of Black people as culturally inferior and deficient. His biography thus helps illuminate how reformers constructed an understanding of diseased alleys and the drivers of their virulent campaign to eliminate them.

Alleys and historical GIS

HGIS unlocks new possibilities for interpreting sources and historical questions from a spatial perspective. Alleys represent a distinct pattern of segregation that differs from the neighborhood-level separation typically thought of today, rendering a spatial lens particularly appropriate to understand how white reformers perceived their relationship to alleys, and to assess epidemiological relationships between alleys and disease.

Although there are several prior efforts to spatially analyze alleys’ distribution and characteristics (Borchert Reference Borchert1982; Logan et al. Reference Logan, Jindrich, Shin and Zhang2011; Logan Reference Logan2017; Prologue DC Reference Prologuen.d.), this work has not to date included epidemiological data, nor used the BOH source. To geolocate the alleys, I used the Sanborn fire insurance maps from 1903–16 and the 1912 Monday Evening Club directory. HGIS can then be used to spatially represent demographic and epidemiological data from the BOH reports. The reports provide tables presenting the population, number of all-cause deaths, and number of deaths due to a specified set of infectious diseases among residents in the prior year for every inhabited alley. Very few annual reports other than 1912–13 and 1913–14 contain all of these pieces of information. Fortunately, this time period was also critical in the campaign to eradicate unsanitary alley conditions (likely why the data was collected at this time and not others).

Mapping alleys from this period presents significant challenges. Beyond general changes in the street grid, most alleys were closed to residential use and their names were eliminated throughout the 20th century. Furthermore, reflecting alleys’ marginal status, their names were informal and changed frequently (Farrar Reference Farrar2008: 64). The use of multiple sources was helpful in cross-referencing to identify an alley that had multiple names. However, there are several limitations to the accuracy of matching alley locations and data. Some alleys were listed only in the 1913 or only in the 1914 report. It was difficult to determine whether the alley had gained or lost all residents between the two years, or if it was simply missed in data collection one year. I opted for the former interpretation, but if incorrect, this may have skewed my data towards a lower population for these alleys, since I averaged the population between two years in the population data. A limitation to contemporary data on alleys more generally is that surveyors’ population estimates are likely conservative, due to fear of entering alleys and alley residents’ unwillingness to engage with the outsiders (Borchert Reference Borchert1982: 45; Washington Post 1893). A final limitation is that comparable epidemiological data is not available for individual streets as for individual alleys in the BOH dataset; thus, I can only compare street and alley data on an aggregated level.

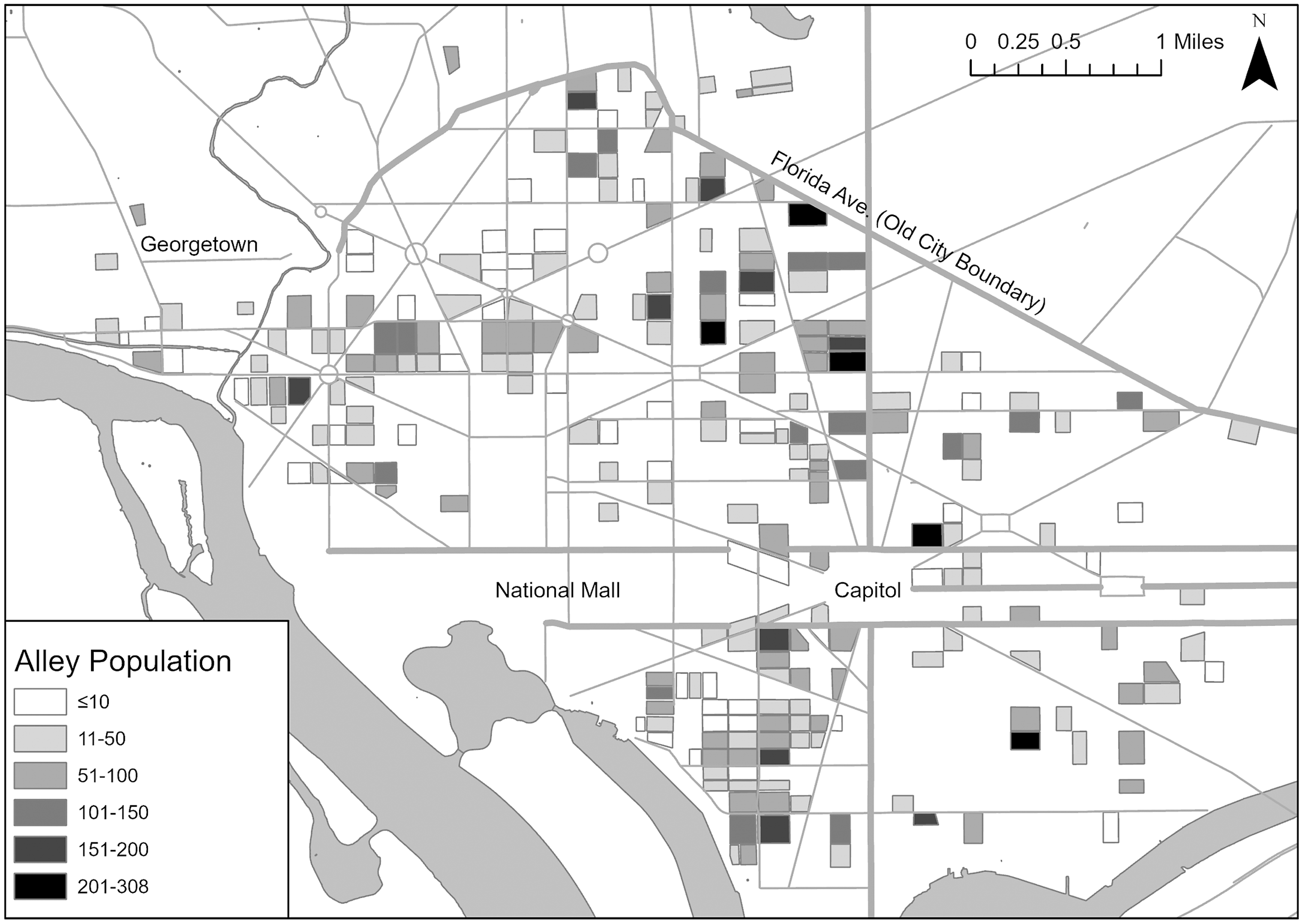

The spatial scale and configuration of segregation

The fine-scale analysis afforded by mapping individual alleys is particularly useful for considering the meaning of segregation in the early 20th century. DC’s master city plan allowed for wide, deep lots, with service alleys that cut through the block. This allowed for the creation of smaller lots with smaller homes facing the alley in the rear of the street homes – intensifying as the population boomed following the Civil War, especially with formerly enslaved people, and a housing crunch ensued. The number of alley residents increased from around 715 residents in 1858 (Borchert Reference Borchert1982), to an estimated 7,676 to 10,614 residents by 1880 (Borchert Reference Borchert1982; Logan Reference Logan2017; Groves Reference Groves1974) and a probable peak of 18,225 residents by 1897 (Commissioners of the District of Columbia 1897). While initially these homes mainly served unskilled white workers employed nearby, sometimes by their landlord, the construction and ownership of alley homes became more speculative and disconnected from the adjacent streetfront homes, with residents experiencing little contact with distant owners; the alley population also shifted to majority-Black (Borchert Reference Borchert1971; Jones Reference Jones1929). Figure 2 shows the wide distribution of alleys across the city as of 1912–14, along with the size of their populations. Most were relatively small, although some were large, with as many as 308 residents living in the interior of a single block. Inhabited alleys were common in cities up to this point in Britain and the U.S. (Borchert Reference Borchert1982: 224). DC’s “blind” alleys, however, were unique in that they were accessed only by narrow passages and formed “H” or “I” shapes of interconnected lanes, which did not allow for clean sight lines through the block, and thus, were “hidden” from the outside community (Groves Reference Groves1974). Unsurprisingly given they offered poorer-quality housing, alleys’ residents were typically socially marginalized, even in comparison with other Black Washingtonians – often migrants from rural Virginia and Maryland, and holding lower occupational profiles than their Black streetfront counterparts (Borchert Reference Borchert1982; Groves Reference Groves1974, Reference Groves1973).

Figure 2. Population by alley, Old City of Washington, and immediate surrounding area, averaged across the two years of the BOH reports. Throughout, the base map for roads comes from Open Data DC and the base map for rivers comes from University of Virginia.

Researchers long believed that racial residential segregation in U.S. cities was relatively low in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Quantitative analyses of segregation on the ward level indicated that Black urban residents lived in predominantly white wards prior to the Great Migration, with segregation increasing thereafter (e.g., Cutler et al. Reference Cutler, Glaeser and Vigdor1999). However, recent research across a wide range of cities nationwide, drawing on newly-digitized complete census records to examine segregation at levels such as the enumeration district or adjacent households, finds that in fact, segregation existed at smaller scales (Logan et al. Reference Logan, Zhang, Turner and Shertzer2015; Bae and Freeman Reference Bae and Freeman2021; Logan et al. Reference Logan, Zhang and Chunyu2015; Logan and Parman Reference Logan and Parman2017), and that the rise in segregation began by 1900 (Logan et al. Reference Logan, Zhang, Turner and Shertzer2015).

In particular, emerging research suggests the role not only of spatial scale of segregation but also of the spatial configuration or pattern of segregation within small areas, with qualitatively different types of spaces segregated from one another although close together (Logan and Bellman Reference Logan and Bellman2016; Grigoryeva and Ruef Reference Grigoryeva and Ruef2015; Logan and Martinez Reference Logan and Martinez2018). Such typologies include the alley as well as a “backyard” pattern, in which housing was located behind the street-facing house but lacked its own alley access, particularly associated with the legacy of slavery; and side streets, which were narrow like alleys but ran for several blocks parallel to streets (Grigoryeva and Ruef Reference Grigoryeva and Ruef2015; Logan and Martinez Reference Logan and Martinez2018). Grigoryeva and Ruef (Reference Grigoryeva and Ruef2015) define such micro-patterns of segregation as tertiary segregation: “a function of residential street layout or other neighborhood features that influence pedestrian paths,” which allow “social groups [to] be separated […] while living in reasonably close spatial proximity” – as opposed to separation across administrative or political geographic boundaries, creating racialized districts, or across straight-line paths.

Spatial analysis has confirmed this pattern of fine-grained segregation in DC (Grigoryeva and Ruef Reference Grigoryeva and Ruef2015; Logan Reference Logan2017). DC’s Black residents largely lived on distinctly Black street segments, separated from yet very close to white residents. In particular, alleys, which were almost entirely Black while often adjacent to predominantly white streets, exemplify this pattern of tertiary segregation.

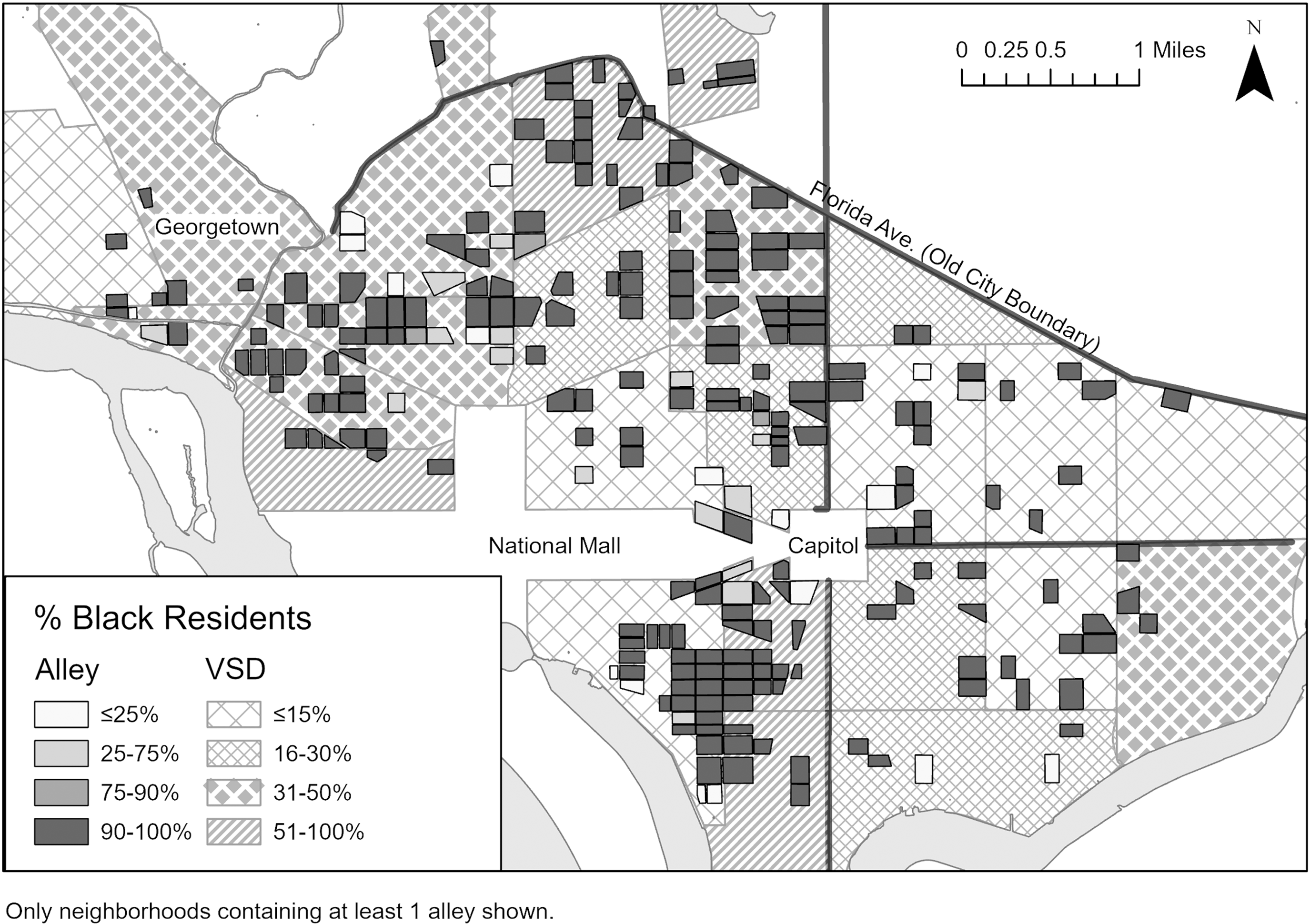

Quantifying and mapping the racial composition of DC’s alleys and neighborhoods, based on the data in the BOH reports (Commissioners of the District of Columbia 1913, 1914), demonstrates these patterns of segregation. I use the geographic unit of vital statistics districts (VSDs) as a proxy for neighborhoods.Footnote 1 As Figure 3 shows, integration was relatively high on a neighborhood level. In VSDs containing alleys, the proportion of Black residents ranged from 8.3% to 79.8%, with a mean of 33.7% and median of 30.4%, against a citywide proportion of 27.9%. Thus, Black and white residents certainly shared neighborhoods. However, Black residents could be segregated in alleys in such neighborhoods. On average in my study period (Table 1), citywide, the vast majority (91.2%) of alley residents were Black, while less than half a percent of the white population lived in alleys. Indeed, as Figure 3 demonstrates, even neighborhoods with a high proportion of white residents contained a substantial population of Black alley residents. It is noteworthy that most Black residents (88.7%) actually lived on streets, and alleys were home to only 3.5% of the city’s residents. However, given that Black people made up a much smaller proportion of the overall population than white people, they still made up only around a quarter of street residents. Therefore, while most Black residents did not live in alleys, alleys were distinctively Black spaces. This distribution of the Black population is similar to Logan’s (Reference Logan2017) calculations for 1880 although the proportion of Black alley residents has slightly increased – at that time, 86.3% of alley residents were Black, and 87.4% of Black residents lived on streets – suggesting that the alley pattern of segregation was largely set by 1880.

Figure 3. Proportion of Black residents in alleys and Vital Statistics Districts, Old City of Washington, and immediate surrounding area, averaged across the two years of the BOH reports.

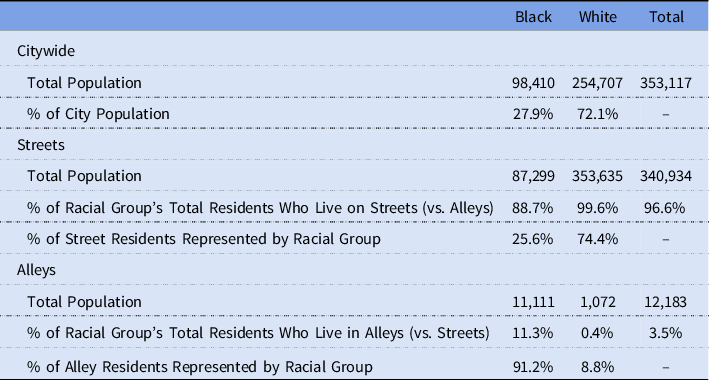

Table 1. Population data for street and alley residents, by race a

Source: Board of Health sections of the 1912–13 and 1913–14 Annual Reports of the Commissioners of the District of Columbia; 1913 and 1914 Reports Data Averaged.

a Population is averaged between the two years in calculating alley population, to provide a more representative number for annual population in this time period.

Figure 4, which maps the race of heads of household in a segment of Northwest DC, reveals this pattern on the local scale.Footnote 2 Households in the interior alleys were near-universally Black. Meanwhile, almost all white residents lived on streets, in some cases on the perimeter of squares containing alleys. It is also worth noting that streets varied much more in their racial composition than alleys: Some street segments were entirely Black, some entirely white, and unlike in alleys, some mixed-race street segments were also present. Thus, although street segments were often segregated from one another, the street typology was not racialized in the same way as the alley typology. This is similar to Logan’s (Reference Logan2017) map of an area containing racially homogenous alleys and white or mixed-race streets. (The area on Logan’s map did not include as many all-Black street segments as mine, however, but this could be due to case selection. He finds that the average Black person lived on a street or alley segment that was 68% Black but does not distinguish the two typologies. Thus, possible change in prevalence of segregated Black vs. mixed-race streets is unclear.)

Figure 4. Map of an area of NW DC, showing the race of head of household for both alley and street residents. Each dot represents one head of household. Squares containing alleys are shaded. Based on Urban Transition HGIS Project Geographic Reference File of 1910 census. 1903 Sanborn and 1913 Baist fire insurance maps used for street grid and building locations.

To date, research on tertiary segregation has consisted of spatial and quantitative analyses identifying its existence. However, this then raises the question of its social meaning and how it was experienced. Many researchers, based on findings of low ward-level segregation, have argued that shared neighborhoods reflected an age of more fluid race relations. Massey & Denton (Reference Massey and Denton1993, 17), for example, suggest that “the two racial groups moved in a common social world, spoke a common language, shared a common culture, and interacted regularly on a personal basis.” Likewise, researchers have suggested that the racialization of space arose only with the development of neighborhood-level segregation, which enabled association of the presence of Black residents with particular areas, and their linkage with adverse conditions and behaviors (Gotham Reference Gotham2014). Yet the distinction and separation between alleys and streets suggests that geographic proximity of white and Black residents was not an indicator of racial tolerance and that racialization of space was already occurring. Indeed, if segregation was already present by this period, and its rise in intensity and scale had already begun, then it is unlikely that patterns such as alleys entailed such intermingling and harmony. Evidence of housing discrimination, spatial stigma, and hostility towards Black residents in politics, employment, and education during this period, further contradict rosy interpretations (Freeman Reference Freeman2019). Rather, we can more properly think of these small Black residential areas as nascent ghettos (Freeman Reference Freeman2019; Logan et al. Reference Logan, Zhang and Chunyu2015). Configurations such as the alley still maintained meaningful “symbolic boundaries” between racialized groups (Logan and Martinez Reference Logan and Martinez2018), or what Gunnar Myrdal (Reference Myrdal1944: 621) described as segregation by “ceremonial distance” as opposed to spatial distance. How did white residents react to close proximity to the racialized and marginalized space of the alley? Further, the growing intensity and scale of segregation occurring during this period raise the little-examined question of the processes by which tertiary segregation transformed into racialized districts. On the enumeration district level, Logan and Martinez (Reference Logan and Martinez2018) calculate a Dissimilarity Index for DC of .36 and Isolation Index for Black residents of .43 in 1880; by 1910, Bae and Freeman (Reference Bae and Freeman2021) find that the city’s Dissimilarity Index had increased to .46 and Isolation Index to .48, and by 1920, .58, and .53, respectively. While newly-constructed neighborhoods might be able to exclude Black residents, many already-built neighborhoods already contained both Black and white residents, and thus, the shift to racialized districts would require one group of residents to leave. What happened to alleys as micro-segregation became macro-segregation?

I argue that the two questions are related. If white residents did not share a common world with Black residents due to racial animus, and relegated them to separate spaces, it would seem surprising if they viewed with equanimity substantial Black communities literally in their own backyards. Indeed, white residents did not view benignly and coexist peacefully with the Black alley communities in their midst, but rather, reacted strongly against their proximity and agitated for their elimination. Reformers’ framing of epidemiological statistics offers a lens into these dynamics.

Alleys, health, and the campaign for eradication

Jones’ Monday Evening Club alley directory (Reference Jones1912), as well as an editorial (Reference Jones1913), devoted significant attention to condemning the health conditions in alleys. He pointed to overall mortality rates of 30.09 per thousand in alleys vs. 17.56 in streets and observed that mortality rates by race were higher among alley dwellers than street dwellers for all four infectious diseases which were supposedly the most common causes of death. Jones’ preoccupation with the health conditions in alleys reflected the concern in the broader alley reform movement. Alleys’ unsanitary conditions and corresponding high rates of disease were primary arguments made in a widespread campaign to eliminate alleys, which were regularly described as breeding grounds of disease, plague spots, and human pestholes.

The industrialization and urbanization of the late 1800s and early 1900s brought dramatic population growth, pollution, sanitation challenges, and outbreaks of infectious diseases to many cities. Progressive reformers saw health and housing conditions as intimately intertwined – pointing to unsanitary characteristics such as lack of light, ventilation, or indoor plumbing, as well as overcrowding, as contributing to the spread of infectious diseases and even moral disorder (Foglesong Reference Foglesong1986: 56–88; Boyer Reference Boyer1983: 9–32; Corburn Reference Corburn2007). In DC, the housing reform battle took the form of ongoing efforts to legislate the end of alleys’ residential use. As one 1910 article summarized, there was a “consensus” that Washington should “tear down the old insanitary structures, rebuild with modern and healthful dwellings, let the rental be expended on improvements, and thus wipe out the blot of Washington’s alley conditions” (Washington Post 1910b) – although the rebuilding component was never as clearly defined. Reformers waged vocal and active publicity campaigns to educate the public and attract their support, with a heavy emphasis on graphic, shocking reports, and photographs that detailed squalid conditions (Asch and Musgrove Reference Asch and Musgrove2017: 202). The movement against “unsanitary” alleys went as high as President Theodore Roosevelt, who exclaimed in a State of the Union address (Roosevelt Reference Roosevelt1904) that DC’s “hidden residential alleys are breeding grounds of vice and disease.”

This campaign had reached a high point during the period of my data (Jones Reference Jones1929: 38). Earlier efforts had succeeded in banning construction of new alley dwellings in 1892, as well as creating a board to condemn unsanitary buildings in 1906, which had demolished 375 alley homes within five years (Jones Reference Jones1912). Accordingly, the alley population had declined from its peak of 18,225 residents in 1897, to 11,111 residents by 1913–14. However, reformers sought to eliminate all alley dwellings. They viewed the alley spatial typology itself as inherently conducive to social and physical pathology. As Dr. William Woodward, the city’s health officer, remarked, testifying on behalf of a bill to ban all residence in alleys, “It is not that individual buildings are insanitary,” but rather, “the alley conditions are per se bad” (US Congress 1914b).

Mirroring the broader housing reform campaign, elite religious and civic organizations – rather than Black alley residents themselves – led the charge in DC. The group drafting a bill to eliminate alleys, for example, included representatives from the Board of Trade, the Chamber of Commerce, the Monday Evening Club, and the women’s department of the National Civic Federation (Bicknell Reference Bicknell1914). Alley reform’s leading advocate, Charlotte Hopkins of the Associated Charities, was the granddaughter of a Massachusetts Congressman and president of Harvard University (McManus Reference McManus1934). First Lady Ellen Wilson was such a committed advocate of alley elimination that the passage of the elimination bill was her dying wish (Bicknell Reference Bicknell1915). The alley researcher James Borchert points out that people producing surveys and studies of alley life (often the same as the campaigners) were typically very well-educated and financially well-off (Borchert Reference Borchert1982, 254). Jones encapsulates the stark difference between the backgrounds of reformers and alley residents. He held a Ph.D. from Columbia University and, shortly after the publication of the directory, went on to serve as the director of the influential Phelps-Stokes Fund, a philanthropy focused on education, particularly for African-American and African students (Johnson Reference Johnson2000).

Specifically, like Jones, other reformers also emphasized alleys as unsanitary plague spots in their appeals to the public, frequently presenting statistics on the higher rates of disease in alleys. Testifying on behalf of the bill to eradicate alleys, for example, Frederick Simmons, of DC’s Board of Commissioners, noted that “the medical statistics showed the very heavy mortality which occurred in the inhabited alleys” (US Congress 1914a). Congressman William P. Borland, remarking on the same statistics as Jones, went so far as to insist that “the death rate of the District of Columbia, which is much larger than it ought to be in a national capital, is due almost entirely to the unhealthful condition of these alleys” (emphasis added) (US Congress 1914a).

However, alley reformers presented the statistics in a misleading fashion, overstating alleys’ impact. To shed light on why they might do so, I first explore how concerns regarding unsanitary conditions and disease in alleys were not necessarily motivated by a desire to promote alley residents’ well-being, but rather, fear that disease might spread outside of the alleys to impact the rest of DC’s residents.

Spatial proximity motivates fear

In an editorial (1913), Thomas Jesse Jones explicitly tied alleys’ presence to the risk of the spread of infectious disease to street households. He argued that the previously-mentioned dismal statistics he presented on mortality in alleys compared to streets should be “understood as a measure of contagion and infection from the alley inhabitants to the street population:”

Disease in them, therefore, means more than the suffering and death of alley population: it means the possible and even probable infection of the comfortable and supposedly sanitary houses of the street. One needs only recall the typhoid fly and the malaria mosquito and their trips from the house of the poor to the house of the rich to realize the close relationship that may be established between the consumptive of the alley and the resident of the street.

Jones was particularly concerned with the now-familiar point of alleys’ proximity to elite homes and institutions: “these houses with their diseases and crime fill the center of many blocks rimmed with splendid houses and hotels.” He impressed upon his readers that “A glance at the map of Washington shows the dangerous proximity of these disease centers to the best residential blocks of the city:” “Even the White House, and the northwest section, famous for its palatial homes of national rulers and foreign ambassadors are not free from these menacing blots.” The tertiary model of segregation thus created much higher risk for elites than neighborhood-level segregation: “The insanitary houses of most cities are localized in certain sections away from the homes of the prosperous. This separation affords some protection. In Washington, this is not the case.”

Jones’ arguments are representative of the preoccupations of the alley clearance movement. Reports on the “slum” conditions in alleys or pleas for action often emphasized that alleys were not isolated in some discrete part of the city, but rather, were close even to DC’s most elite streets and residents (e.g., see Figure 5, highlighting the Capitol building). For example, the Washington Post (1909) anxiously observed that “In every quarter of the Capital, one may find them, hidden only a few feet back of respectable front doors, where diplomats and statesmen come and go.” Likewise, the Citizens’ Relief Association and the Associated Charities noted that “some of the worst alleys are located in northwest Washington within a stone’s throw of palatial mansions, magnificent churches, monuments, and the edifices of the national government” (Washington Post 1901). Congressman William Borland fretted that “it is impossible in the city of Washington to separate the population from the contagion of the alley slums,” unlike in industrial cities where slums were concentrated near industry and away from purely residential neighborhoods (US Congress 1913).

Figure 5. Willow Tree Alley. Reformers emphasized alleys’ proximity to elite institutions such as the Capitol. Source: Neglected Neighbors.

Other reformers also then often stressed the possibility for alleys’ problems, including disease, to spread beyond their borders to the surrounding streets. Alley residents “pass[ed] daily back and forth between their homes and yours, weav[ing] an inseparable bond which threatens the welfare of the entire community” (Bicknell Reference Bicknell1912), and thus, reformers compared alley residents to “apples tossing about in a common barrel, in which the rottenness of the bad fruit is given every opportunity to infect all the rest” (Weller and Weller Reference Weller and Winston Weller1909: 69). The Washington Post deemed the city’s slums “breeding places of disease and death, responsible […] in no small measure for many deaths beyond their limits, just as the felon in the old London docks carried jail fever to the judge on the bench” (Washington Post 1910a). This rhetoric particularly emphasized physical proximity: “Washington is honeycombed with filthy alleys, spreading disease in even the most beautiful parts of the city” (Washington Herald 1910). Jacob Riis (Reference Riis1997 [1890]), author of the influential tenement exposé How the Other Half Lives (1890), agreed – dramatically proclaiming in a speech to the Associated Charities that “the influences [alleys] exert threaten you, for the handsome block, in whose center lies the festering mass of corruption, is like an apple with a rotten core” (Washington Post 1903).

For example, replicating Jones’ concern with “the typhoid fly,” Charles Frederick Weller and Eugenia Winston Weller’s book on life in alleys, Neglected Neighbors, described a case of death from typhoid fever in Snow’s Court, whose victim used an unsanitary privy (Figure 6). They emphasized that “This case of typhoid might readily supply germs to infect the resourceful residents on Pennsylvania avenue, less than two blocks distant, the worshipers in the prosperous-looking church, which occupies a nearby corner, and the scientists in the United States Weather Bureau two squares away” (Reference Weller and Winston Weller1909, 94). In another example – describing an alley located near the British Embassy, the city’s wealthiest Presbyterian church, a fashionable apartment house “in all its magnificence,” and “very stylish thoroughfares” – the Wellers note that “Flies, carrying typhoid fever germs from the open box toilets of ‘Chinch Row’, could readily enter neighboring kitchens and infect the food or milk of the wealthiest citizens of Washington or of the nation’s ablest statesmen” (Reference Weller and Winston Weller1909, 215).

Figure 6. The Wellers’ depiction of an unsanitary privy in Snow’s Court. Source: Neglected Neighbors.

Legislators, too, adopted this view. Congressman Borland, during a 1914 debate on the bill to eliminate alleys, made the now-familiar observation that the alleys “surround the houses of the average citizen and the respectable toilers; they lurk behind the palaces of the wealthy, and they flourish under the very shadow of the Dome of the Capitol.” He then went on to emphasize the corresponding risk of broader disease transmission, placed in the context of alleys’ spatial proximity: “These alleys are centers of disease. They radiate out insanitary influences” (US Congress 1914a).

Reformers used this risk of the spread of disease to urge action to protect non-alley residents (Gillette Reference Gillette2006: 115–16). The call to white Washington thus appealed to self-interest: as an editorial urging that alleys be “cleaned up” noted, “Selfishness alone […] may prove a stiff enough broom to sweep the city clean” (Washington Post 1909). William Jennings Bryan echoed this argument on a visit to Washington, contending that “selfish […] self-preservation” was the first reason to clear the alleys, given what he claimed to be twice as high of a death rate: “Disease breeds in those places. When a plague enters a city it is invariably by way of its alleys and slums” (Washington Post 1913). A Washington Post (1896) described alleys as a “danger to the many,” insisting, “These wretched slums are a menace to public health […] Washington is threatened, morally and physically, by their existence.” Similarly, Clare de Graffenreid (Reference Graffenreid1896), who had been hired to conduct a survey on alley homes by the Woman’s Anthropological Society, argued that alley conditions “are not of mere local or personal interest, as affecting the comfort and health of alley denizens. They are, on the contrary, of wide personal interest, since they bear on the introduction into an otherwise healthy community of filth, disease, and epidemics.”

This self-preservation motivation was common to the housing reform campaigns of the time. Elite Progressive housing reformers were not driven to eradicate poor conditions merely by concern for the well-being of the poor. Rather, fearful of the unrest and turmoil among urban masses accompanying chaotic urbanization, they sought social control to stem off the consequences that slums might incur for the better-off – such as public health and safety risks, social unrest, and reduced real estate values (Marcuse Reference Marcuse1980; Foglesong Reference Foglesong1986: 56–88; Boyer Reference Boyer1983: 9–32). As Jacob Riis exclaimed in How the Other Half Lives (1890), tenements were “the hot-beds of the epidemics that carry death to rich and poor alike.” Thus, their belief that physical improvements could address pathologies of both environments and people (Corburn Reference Corburn2007) was informed by both their paternalistic sense of elite superiority and their self-interest. In DC, the alley spatial typology added urgency to such infectious disease concerns.

White reformers were keenly aware of alleys’ spatial proximity, and believing that alleys were disease-ridden plague spots, they feared the possibilities for nearby disease to spread to their own communities. Was this fear justified?

Race, place, and disease

As previously mentioned, Jones cited 1909 mortality rates of 30.09 per thousand in alleys and 17.56 in streets – certainly a dramatic difference that merits concern. Yet correlation does not necessarily indicate causation. A closer examination of BOH data reveals that the gap between street and alley mortality significantly narrowed when accounting for racial composition, suggesting that conditions linked to racialized marginalization, not alleys themselves, largely explained the differences. Further, alleys’ comparatively small population meant that their impact on DC’s mortality was limited: the vast majority of deaths, including from infectious diseases, occurred among street residents.

Jones’ 1909 statistics are similar to the data for my 1912–14 study period (Table 2). Analysis of the 1912–14 data beyond the descriptive statistics provided by the BOH reports provides further insights. Alley residents represented 11.3% of the Black population and a relatively similar proportion of their deaths, 13.3%. Moreover, alley residents account for only 5.8% of the city’s deaths, which although certainly higher than their proportion of the population (3.5%), remains quite small in comparison to the 94.2% of deaths occurring among street residents. Thus, it is hard to support assertions blaming alleys for DC’s excess mortality, such as Congressman Borland’s claim that the city’s high mortality rate was due “almost entirely” to alleys.

Table 2. Mortality in streets and alleys, overall and infectious disease, by race a

Source: Board of Health sections of the 1912–13 and 1913–14 Annual Reports of the Commissioners of the District of Columbia; 1913 and 1914 Reports Data Averaged).

a Data is averaged between the two years in calculating mortality, to provide a more representative number for mortality in this time period.

b Includes diphtheria, scarlet fever, typhoid fever, whooping cough, diarrhea (under 2 years), pneumonia, bronchitis, pulmonary congestion, and pulmonary tuberculosis.

Focusing specifically on infectious disease, the picture is similar: Alley residents died at higher rates, but the difference was much smaller when accounting for race. Overall, alley residents faced over twice as high of a risk of dying from infectious diseases than street residents (10.8 vs. 4.4 per 1000). However, among Black residents, the risk per 1000 residents was 8.5 for street residents and 11.3 for alley residents – a difference that, while not inconsiderable, is much less pronounced. Likewise, 33.8% of deaths among Black street residents were attributable to infectious disease, compared to a similar 37.3% of those among Black alley residents. Out of all the Black residents who died of infectious disease, 14.5% were alley residents – not much higher than their proportion of the Black population, 11.3%. (The difference is larger for white residents, 21.4% in streets, 36.4% in alleys; but as only six white alley residents on average died each year of any infectious disease, the power of these numbers is limited.) Alley residents made up a greater proportion of people citywide who died from infectious disease (8.6%) than they did of people who died from all causes (5.8%); but again, the vast majority of people who died of infectious disease were street residents.

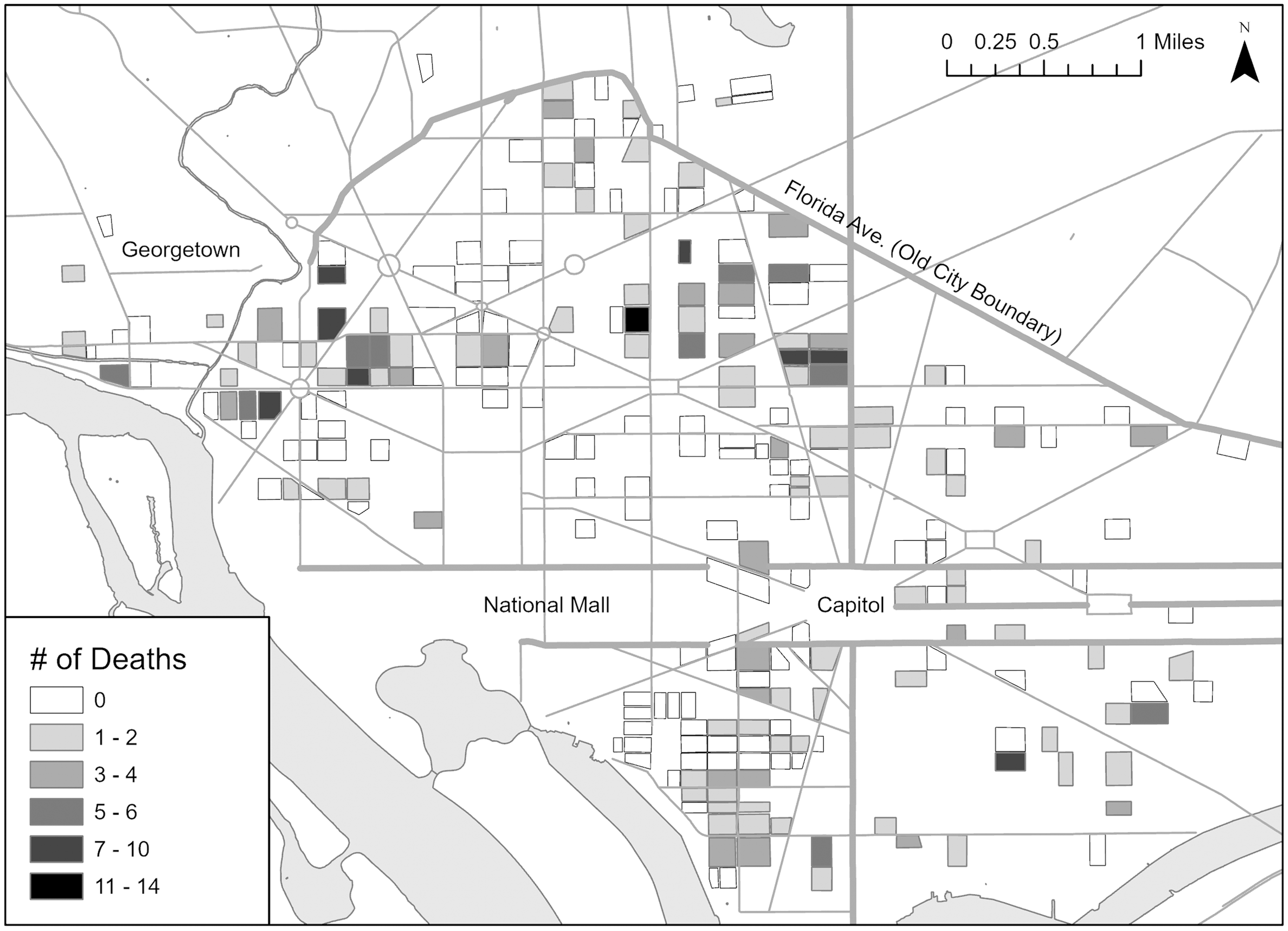

Mapping the total number of deaths from the infectious diseases tracked by the BOH in alleys in the 1913 and 1914 reports (Figure 7) similarly fails to paint a picture of terrifying epidemics.Footnote 3 Over this two-year period, 53% of inhabited alleys (131 out of 246) had no deaths from these diseases whatsoever. In 72 of the 115 alleys where such deaths did occur (or 63% of these 115), they were limited to one or two deaths. Only 17% of alleys in total (43) saw more than two residents die. I provide absolute numbers rather than rates given the small populations of many alleys, but the alleys with 3+ deaths did also tend to have proportionally larger populations.

Figure 7. Total deaths from select infectious diseases, by alley, in total across the two years of the BOH reports.

How, then, can we understand the health disparities between alleys and streets? Almost all alley residents were Black, and Black residents experienced extreme marginalization, impacting morbidity and mortality: For example, they engaged in the most difficult and dangerous physical labor, had less income available to afford a healthy diet, and had difficulty accessing and paying for medical care (Borchert Reference Borchert1982: 184,221). We would expect Black residents to have higher mortality rates than white residents, and therefore, expect alleys, as almost entirely Black places, to have higher mortality rates than streets, as majority-white places. This still leaves the slightly higher rates of disease among Black alley residents relative to Black street residents, but unsanitary alley conditions are not the only factor that could explain this. Because alley residents were even more socially marginalized than Black street residents – often migrants from the country, working the most undesirable jobs – they might have borne a higher burden of disease no matter where they lived.

Likewise, when we return to the 1909 BOH report from which Jones’ data came, and limit the comparison to Black street and alley residents for the same time period, rather than the raw mortality rate for all residents without accounting for racial composition, we see a much smaller difference: 31.94 in alleys (vs. 30.09), 25.84 in streets (vs. 17.56) (Commissioners of the District of Columbia 1909). Jones presumably had access to this information, as it was presented in the same table of the BOH report as the overall street vs. alley mortality rate. Yet he selectively highlighted the statistic that fit his narrative.

This error in Jones’ excessive causal attribution of health disparities to the alleys is shown clearly in his presentation of infant mortality rates. In a speech to the Young Women’s Christian Association, he pointed to the alley death rate of 373 per 1000 infants < 1-year-old, and argued that if alley residents “could be housed elsewhere,” this rate “could be reduced at least to 200 for every 1,000” (Washington Post 1912b). Similarly, in his editorial, he drew a comparison between the 373 per 1000 overall death rates for infants < 1-year-old in alleys with that of 158 per 1000 in streets (Jones Reference Jones1913). However, the rate among Black infants living on streets was still 287 per 1000 – lower than in alleys, but still much higher than 200 or 158. Further, this rate was more than twice as high as that for white street residents, who saw 115 deaths per 1000 infants, so street residence did not eliminate racial disparities (Commissioners of the District of Columbia 1909). Clearly, alleys did not fully explain the health disparities faced by alley residents, which reformers’ selective statistics concealed, and evicting residents from alleys would not result in the improvements Jones claimed.

Turning to specific infectious diseases, Jones also discussed mortality rates for alleys and streets across four diseases that were disaggregated by race, despite not doing so for overall mortality rates: pneumonia, tuberculosis, whooping cough, and diarrhea for children under 2 years. Black alley residents were indeed more likely to die from these diseases than Black street residents, strikingly so in the case of pneumonia. This is perhaps unsurprising given that these diseases are linked particularly closely to poverty and to environmental conditions such as crowding and poor sanitation. However, here too a caveat to Jones’ claims is necessary. An examination of the 1909 BOH report reveals that although Jones claimed to select the four most common causes of death, death from typhoid fever was much more common than from whooping cough (114 deaths vs. 30). Similar data on typhoid fever was provided in the report but not included by Jones. For this condition, the mortality rate among Black street residents was substantially higher than among Black alley residents (Commissioners of the District of Columbia 1909). This exclusion is especially noteworthy given Jones’ mention of the threat of the “typhoid fly” from alleys. Thus, he again omitted information that countered his narrative.

Although health outcomes were indeed worse in alleys, the statistics suggest that reformers exaggerated their claims regarding the degree to which DC’s overall mortality rate was influenced by alley mortality, as well as the direct impact of alleys. The obsessive fear of alleys causing disease does not appear proportional to the threat. Rather, the data suggest that Black residents, in general, had high mortality rates – which, given that alleys were nearly entirely Black, meant that alleys would likely have higher mortality rates than streets. The far more startling statistic, indeed, is how much greater a burden of disease all-Black residents bore compared to white residents, wherever they lived. The mortality rate from infectious disease was almost three times higher among Black street residents than white. While certainly alley housing was crowded and substandard, reformers misinterpreted what they saw and overestimated the extent to which housing caused, rather than was correlated with, rates of disease.

It is true that reformers did not have tools such as HGIS available to analyze patterns of disease, which could have helped them to recognize this alternative interpretation. Further, detailed statistics on alleys were only available for a limited number of years. However, this still leaves the question of why reformers would have so strongly tended toward viewing alleys as disease-ridden. Moreover, as Jones’ misinterpretation of the available statistics shows, reformers ignored epidemiological evidence that they did have. Their zeal to eliminate alley dwellings on sanitary grounds is all the more puzzling given that, as previously mentioned, individual unsanitary dwellings could be legally condemned and demolished, and thus, those that remained by this point generally met a threshold of safety and sanitation (Farrar Reference Farrar2008: 62). How, then, are we to understand reformers’ rather obsessive understanding of alleys as unsanitary and diseased?

Progressives, race, and space

I now turn to an exploration of how reformers’ understanding of Black people and Black space as deviant and pathological created a construction of the “breeding ground of disease.” Returning to Jones’ career, which was steeped in the promotion of white supremacy in the guise of virtuously championing Black education, sheds light on how reformers’ paternalism and prejudices could influence their interpretations of alley life and residents. I use the lens of Black geographies scholarship, which offers critical perspective into how racism is enacted spatially – as Black people are relegated to “spaces of otherness,” and such geographies and their inhabitants are mutually rendered as “inhuman, dead, and dying” (McKittrick Reference McKittrick2013). Although most Black residents lived on streets, the alley typology was prime for such racialization: Given that over 90% of alleys’ residents were Black, alleys became encoded as Black spaces, while conversely, streets were more difficult to compartmentalize as distinctively Black. Yet simultaneously, Black geographies contest this framing by emphasizing that Black places constitute sites of production for alternative spatial imaginaries.

Jones believed firmly in racial hierarchy, holding that Black people and other groups not perceived as fully white had not “evolved” to the same stage of civilization as Anglo-Saxon white people. He advocated providing narrow accommodationist vocational training for Black students, teaching them to be docile and industrial within the status quo. For example, in a Department of Education study he led on schools for Black students, Jones highlighted the ways that supposed characteristics of Black people justified inferior education (e.g., they should receive “simple manual training” because “the Negro’s highly emotional nature requires for balance as much as possible of the concrete and definite”) (Jones Reference Jones1917, 23). He sought to assimilate Black people to Anglo-Saxon norms, which he believed to be inherently superior, but only insofar as it led them to understand their present subordination and suited their ability to perform their menial role in their current stage of civilizational “evolution”. He did reject the idea of absolute and eternal inferiority of Black people, contemplating that in the distant future, they might come to be capable of higher achievement if they successfully assimilated and “matured,” but for now, he felt, they must recognize their inferior station and learn to perform the associated responsibilities to white people’s satisfaction (Johnson Reference Johnson2000). By imbibing such notions as the need to strive to “develop” in order to “become the equals of other races,” a Black pupil might, “instead of regarding the difficulties of his race as the oppression of a weaker by the stronger,” view them as “the natural difficulties which almost every race has been compelled to overcome in its upward movement” (Jones Reference Jones1906: 5).

Jones also applied his bifurcated educational model in colonial contexts across the United States, Asia, and Africa, where his views of racial hierarchies are further evident (Johnson Reference Johnson2000). He remarked, for example, that “As the physical elements of the mammals have a distinct similarity from the lower stages to the highest, including man, so the elements of primitive society parallel those of the highest communities of Europe and America” (Jones Reference Jones1926: 19). Paralleling arguments about alleys, Jones claimed that sanitary campaigns must not “be limited to the higher levels of civilization” but must also be expanded to “primitive people” on the grounds that “plagues have a way of spreading into the higher group” (Jones Reference Jones1926: 50–51).

Jones’ public disputes with W.E.B. Du Bois, whose educational philosophy was diametrically opposed to Jones’, underscore the white supremacism of his positions. Du Bois advocated for Black people to fully develop their intellectual capacities. He called out white prejudice as the cause of Black inequality and wanted Black education to enable students to understand and challenge such structures (Johnson Reference Johnson2000). Du Bois (Reference Du Bois1918) argued that Jones’ recommended model of industrial schools – “training schools for cheap labor and menial servants” – would “deliberately shut the door of opportunity in the face of bright Negro students”. Of particular note for the alley reform movement, Du Bois criticized Jones, as a white man, for taking a range of leadership roles to make decisions about what was ‘best’ for Black people, noting philanthropy’s tendency to “work for the Negro rather than with him” (ibid.). “Are we going to consent to have our interests represented in the important councils of the world – missionary boards, educational committees, in all activities for social uplift – by white men who speak for us, on the theory that we can not or should not speak for ourselves?” Du Bois asked (Reference Du Bois1921). Du Bois’ views were shared by other Black leaders. Carter G. Woodson, editor of the Journal of Negro History, declared that “an investigation will show that Dr. Jones is detested by ninety-five percent of all Negroes who are seriously concerned with the uplift of the race,” because he had made himself “the self-made white leader of the Negroes, exercising the exclusive privilege of informing white people as to who is a good Negro and who is a bad one, what school is worthy of support and what not, and how the Negroes should be helped and how not” (quoted in Hine Reference Hine1986). W.M. Brewer, Woodson’s successor in that position, called Jones “the most evil person that touched Negro life from 1902–1950” (quoted in Ellis Reference Ellis2013).

Jones’ paternalistic belief in the inferiority and deficiency of the Black people he was ‘helping’ indicate a predisposition to view alley residents as pathological, and an inability or unwillingness to view the conditions in Black communities in context and question the social structures producing inequality. His approach of speaking for, rather than with, Black residents also decreases the possibility that he could develop valid insight beyond his own preexisting beliefs. Altogether, then, such views would make it unlikely that Jones could accurately understand and interpret alley conditions, instead seeing them refracted through the lens of his own racist sense of superiority.

Jones’ biases are characteristic of reformers’ attitudes. For example, in a revealing exchange, the reformer Grace Bicknell conveyed to First Lady Ellen Wilson, on an alley tour to recruit her to the cause, her “great desire that [alley residents] might one day be forced to live where they would be subjected to the supervision and restraint” of the street and its mainstream society. The First Lady, who adopted alley elimination as a pet cause, responded that “her mother and grandmother, who were both slave-owners, taught her from her childhood that it was the duty of the southern Christian woman to work for the good of the Negroes” (Bicknell Reference Bicknell1915). Far removed socially from alley residents, reformers interpreted perceived failures to adhere to their own norms or achieve their own standards of living as indicators of pathological inferiority and deviance. Reformers’ arguments did not seek to be representative of or even include the views of alley residents themselves. Indeed, their social distance from alley residents made it difficult for researchers to even gather information from distrustful residents and complete any fieldwork (Borchert Reference Borchert1982: 258). One white woman moving to an alley to conduct her dissertation research reported little contact with her Black neighbors across the first 17 months of residency, and contact with only four families after that, observing that “it is difficult for a white woman to move into a segregated district, and friendly intercourse grows slowly.” The dissertation was titled “A Deviant Social Situation,” perhaps indicating an attitude that may have made her neighbors justifiably wary of bonding with her (Sellew Reference Sellew1938). Accordingly, reformers investigating alley conditions failed to understand alley life on its own terms or consider alternative explanations for what they saw. They envisioned alleys, as Black spaces, to be inherently unsanitary and diseased, overstating the horrors of conditions in alleys and their effects on residents’ health as they found in the data simply what they expected to see.

This reading of reformers’ attitude aligns with other work on elites’ discursive co-construction of diseased racialized bodies and space, naturalized with scientific statistics. Samuel K. Roberts, a researcher of African-American urban history, observes in his work on tuberculosis in Baltimore that health officials’ maps of tuberculosis cases emphasized the spatial correlation between Blackness and disease without providing context. Thus, “racialized space was to be regarded as a simultaneous expression and a cause of illness” (Roberts Reference Roberts2009, 108). Similarly, historian Nayan Shah, studying the politics of public health in San Francisco’s Chinatown, examines how “health authorities readily conflated the physical condition of Chinatown with the characteristics of Chinese people” (Shah Reference Shah2001: 1–2) – viewing Chinese immigrants as filthy, unhygienic, and diseased while failing to consider how discrimination had pushed them into poorer-quality, crowded housing. Through this lens, unsanitary physical conditions thus served both as “evidence of moral turpitude and as an incubator of fatal epidemics” (ibid., 22).

It is also illuminating to consider approaches that reformers did not adopt. Reformers generally placed much less emphasis on ensuring former alley residents would have access to sanitary housing after eviction – failing to adequately consider how housing instability, homelessness, or displacement to unfamiliar territory might impact their health. Certainly, some reformers took interest in finding ways to construct sanitary low-cost housing, but most expressed little concern over the residents’ fate. Moreover, the movement did not advocate for structural reforms that might have alleviated poor housing conditions but threatened the social hierarchy from which reformers benefited. Conspicuously, housing discrimination limited the housing supply available to Black Washingtonians; notably, this same period saw the rise of racially restrictive covenants (Borchert Reference Borchert1982: 7–9, 14–15; Shoenfeld and Cherkasky Reference Shoenfeld and Cherkasky2017; Washington Post 1912a). Yet combating these restrictions did not feature on reformers’ agenda. Similarly, addressing employment discrimination could have helped to address poverty and enable residents to afford higher-quality homes outside alleys. Black residents were generally denied access to skilled employment, facing the most difficult labor for the least pay; this was particularly true for alley dwellers, often migrants whose social class was lower (Borchert Reference Borchert1982: 167, 176–77; Asch and Musgrove Reference Asch and Musgrove2017: 208). Yet reformers not only were silent on this topic, they could even promote unequal employment. For instance, leading alley reformer Charlotte Hopkins lectured Black employees at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing about accepting workplace segregation implemented by President Woodrow Wilson’s administration, saying, “Why will you go where you are not wanted? Do you know that the Democrats are in power? If you people will go along and behave yourselves, and stay away from places where you are not wanted, we may let you hold your places” (Washington Bee 1913). Federal employment had long represented one of the best opportunities for upward economic mobility and stable employment for Black Washingtonians, which was stymied as a result of Wilson’s policies (Asch and Musgrove Reference Asch and Musgrove2017: 220–26). Focusing on the technical reform of eliminating alleys, along with suggesting that alley residents themselves played a role in their poor health, distracted attention from structural reforms that would address inequality experienced by Black alley and street residents. Instead, reformers sought interventions that would amplify the separation of exclusionary white space, while leaving their elite racialized social position unchallenged.

I conclude by calling attention to Black geographic life in alley communities. Black geographies scholarship refuses to equate Black geographic peril with Black death and decay and emphasizes practices of struggle and resistance in the context of such peril, which points toward liberatory spatial imaginaries (McKittrick Reference McKittrick2011). My analysis contests the construction of alleys as pathological or dying spaces by demonstrating the inaccuracy of mainstream portrayals of disease in alley communities. Although a primary analysis of the nature of alley communities is not the main purpose of this study, other work on alleys highlights their tight-knit character and shows how practices that reformers perceived as deviant represented well-suited adaptations to harsh environments of racial oppression (Borchert Reference Borchert1982; Frankel Reference Frankel1995). Such practices point towards the creation of alternative spatial relations that privilege use value and solidarity (Lipsitz Reference Lipsitz2011). Reformers failed to recognize such ways that alley life could be health-promoting and rejected residents’ attachment to their homes and communities in their paternalistic belief that they knew better than residents themselves what was good for them. For example, Grace Bicknell argued to Congress that legislation must completely eradicate alley dwellings, for residents’ own good – because otherwise residents would much prefer to stay there (US Congress 1914b). Although narratives of alley residents’ own perspectives from this period are unfortunately scarce, in such moments we can see a reflection of refusal and resistance.

Conclusion

The sensationalist depiction of alleys as breeding grounds of disease, disproportionate to their actual conditions and effects on health, cannot be understood outside the context of tertiary segregation and white reformers’ prejudices. Thomas Jesse Jones’ work on alleys, in light of his personal background and career, offers a revealing example of how reformers discursively produced pathological alley conditions. Jones’ belief in Black people’s inferiority in a racial hierarchy influenced his interpretations of alleys, predisposing him to view alley residents’ behaviors and homes as deviant from standards he saw as normative and universal. His paternalism led him to feel entitled to represent his construction of alleys as factual while blinding him to the actual shallowness of his understanding of alley life. Rather than recognize the structural factors that actually shaped health disparities among alley residents, reformers collapsed pathological people, health, and space into the “breeding ground of disease.” Further, tertiary segregation stoked reformers’ concern and zeal, as they were keenly aware of alleys’ close proximity to white homes and institutions, and connected this proximity to the possibility that disease could spread the short distance to affect themselves. They sought to reshape racial geographies, preventing contagion through a greater scale of separation.

Building on previous research on tertiary segregation, which has used quantitative data to establish the existence of separation at fine scales, this paper also draws on qualitative sources to assess the social experience of tertiary segregation and implications regarding the processes contributing to the changing scale and intensity of segregation prior to the Great Migration. The campaign against Black inhabited alleys suggests that contrary to conventional understandings, in DC at least the roots of neighborhood-scale ghettoes were not in Black population growth – indeed, the Black share of the population was declining during this period (Gibson and Jung Reference Gibson and Jung2002). Nor did tertiary segregation represent peaceful coexistence or meaningful spatial mixing. Rather, white residents pushed to expel even small “emergent ghettoes” from proximity to their homes. Indeed, only when white residents sought to move into alleys midcentury as the surrounding neighborhoods gentrified were the dwellings spared (Summer Reference Summer2021). Thus, the alley clearance campaign should not be understood as a well-meaning if misguided effort to remediate the living conditions of the poor. Alley clearance instead should be considered alongside other measures during this period that promoted racially homogenous neighborhoods, such as restrictive covenants and racial zoning, together facilitating the rise of segregated neighborhoods. This paper complements such previous work on this topic, which largely concentrates on how newly-built neighborhoods were segregated or how existing segregation was reinforced (e.g., Gordon Reference Gordon2008; Glotzer Reference Glotzer2020), by focusing on the displacement of Black residents within existing neighborhoods to enact the shift from micro- to neighborhood-level segregation.

It is particularly illuminating to consider alley clearance alongside nearby Baltimore’s Progressive mayor’s proposal of both clearance of Black “slums” and implementation of a racial segregation ordinance in 1917–8, on public health grounds (Glotzer Reference Glotzer2020: 110; Brown Reference Brown2021: 73, 78; Power Reference Power1983). To legally justify segregation, he argued that Black residents, “having a much higher rate of tuberculosis,” therefore “constitute a menace to the health of the white population,” drawing on statistics from the Health Department as evidence (The Sun 1918). To remove Black residents from areas they already lived, he further suggested a complementary “elimination of certain conjested sections, populated by Negroes, in which has been noted a very high percentage of deaths from […] communicable diseases” (quoted in Power Reference Power1983). Although the segregation plan was not enacted, its proposal indicates the conceptual linkage in white residents’ minds between spatial proximity, disease, and race; the connection between “slum” clearance and promoting segregation; and the ways that health statistics could be weaponized against populations experiencing health disparities.

Indeed, alley reformers’ campaigns for social control over “pathological” places and people shed light on the pitfalls of progressive housing reform broadly. Historians of urban planning and public health have often looked back approvingly at the progressive era as a time of prioritizing social concerns and reform (Fairchild et al. Reference Fairchild, David Rosner, Bayer and Fried2010; Williams Reference Williams2020). Yet Progressive reformers not only held elitist social control motivations – but more specifically, upheld the production and exploitation of racialized space in pursuit of white interests, following what Williams (Reference Williams2020) identifies as a “racial planning tradition.” As Stein (Reference Stein2018) observes, Progressivism was “defined by both its ameliorative programs and its interest in protecting white, Protestant capitalist power” – and notably, that power was specifically racialized. Black residents were understood as particularly unworthy, needing to strive to improve themselves and rise from the bottom of the civilizational hierarchy. In northern cities, despite the relatively small Black population at this time compared to DC, reformers’ emphasis on disorder and vice naturalized and reinforced ghettoization, and they understood Black residents’ plight as connected to deeply-rooted cultural deficiencies, often excluding Black residents from services such as settlements while supporting ethnic immigrant assimilation into whiteness (Lasch-Quinn Reference Lasch-Quinn1993; Muhammad Reference Muhammad2010; Hartman Reference Hartman2019). In southern cities like Baltimore, meanwhile, Progressives pushed through racial zoning ordinances which required separate residential areas for white and Black residents (Rabin Reference Rabin, Haar and Kayden1989). Complementing these prior accounts, this paper offers a detailed demonstration of how Progressive efforts to address slums as a public health issue should be contextualized within a rationality that embraced racial hierarchy. In particular, the article makes a novel contribution by applying Muhammad’s (Reference Muhammad2010, 277) observation regarding progressive framing of statistics on Black criminality – that “numbers do not speak for themselves” but rather “have always been interpreted, and made meaningful, in a broader political, economic, and social context in which race mattered” – to framing of epidemiological statistics, which have previously been widely accepted regarding alleys. In so doing, I connect critiques of Progressive racialization of space, to Black geographies’ refusal of renderings of Black bodies and places as dead and dying.

There are several implications for further research from these findings. First, historical epidemiological statistics are valuable but should be assessed critically, with attention to potential bias, such as exclusion of relevant variables in data collection and interpretation. The presentation of data is not neutral; data does not exist in a vacuum nor reveal a raw objective truth. Here, alley epidemiology cannot be properly understood without drawing comparisons to Black street residents, rather than the overall population, and accounting for differences in class status between Black street and alley residents. Considering the ways that contemporaries framed and deployed historical epidemiological data can be revealing of their biases and motivations in itself. Second, the experience of and contemporary reaction to tertiary segregation, and the causes of its decline in favor of racialized districts, merit further exploration. Specifically, future work could more granularly examine changes in the intensity and configuration of alley and street segregation over time, and consider factors triggering the alley elimination campaigns, which may hold clues as to the fundamental drivers of the rise in segregation.

Acknowledgements

This paper originated in a course on spatial history and historical GIS taught by Wright Kennedy, and I very gratefully acknowledge his valuable and generous suggestions, feedback, and encouragement throughout its development. The paper has also benefited from Leah Meisterlin’s insights on how to visually convey tertiary segregation, and Helena Rong’s and Ranjani Srinivasan’s feedback on the maps. I presented components of this work at the Social Science History Association’s 2021 conference, and thank attendees for their comments. Suggestions from three anonymous reviewers and the journal’s editors have much strengthened the paper.

Competing interests

I report consulting fees from Delos Living, unrelated to this work.