Since the 1800s, the housing market has figured prominently during economic crises, as a signal, expression, partial cause, or all three. Arguably, with increased leveraging and the globalization of finance, its significance has grown. Regardless, its role has differed in each downturn. In 2008/9, the high level of homeownership, coupled with high-ratio mortgages and risky debt securitization, meant that housing helped precipitate a financial crisis. The epicenter, and worst-affected, was the United States, where many borrowers ended up underwater (Field Reference Field, White, Snowden and Fishback2014). Housing’s role during the Great Depression of the 1930s was different because homeowners were fewer, private lenders more prominent, and financial markets more circumscribed. But, as borrowers and lenders struggled, while governments scrambled to act, housing dramatized a crisis that affected millions.

A similar drama played out in Canada, the United States, Australia, and Britain. The four countries used variations on a shared property law, all favored homeownership, and small landlords were the norm (e.g. Calman Reference McCalman1984: 45, 172; Beaumont Reference Beaumont2022: 345). In varying degrees, private lenders were common (Heales and Kirby Reference Heales and Kirby1938: 4–6; Merrett Reference Merrett and Troy2000). All four were deeply affected by the Depression, although England less so, supporting a construction boom for the middle class (Schedvin Reference Schedvin1970; Scott Reference Scott2013: 99). Evictions, mortgage arrears, and defaults were lower there (Ashworth Reference Ashworth1980: 90; Scott Reference Scott2013: 231). But, in varying degrees, there was a common dynamic.

Some parts of this story are well-known. Out of work, tenants fell behind on their rent and faced eviction. Indebted homeowners, struggling with mortgage and property tax payments, were threatened with foreclosure. Depositors drew heavily on savings and, saddled with unmarketable properties, lending institutions went bankrupt. Compelled to intervene, federal governments became permanently involved in the housing market. But these are only the most visible parts of the story (Harris Reference Harris2023a). When tenants failed to pay rent, or left apartments and houses vacant, landlords had a problem. If lending institutions struggled, so did the private investors who provided more mortgages than any type of institutional lender. And, for owners and investors alike, statistics on foreclosures give an incomplete picture: facing the inevitable, many mortgagors gave up their properties voluntarily, avoiding court. In various ways, then, much of the Depression’s housing crisis has remained invisible. Considering landlords, private investors, and voluntary “defaults,” as well as distressed homeowners and the sometimes militant tenants, this paper uses a Canadian case study to show the part played by all agents in the market. In particular, it is concerned with who lost property, to whom, and how.Footnote 1

It is important to understand the part played by all the major players because, as U.S. federal housing experts, notably Ernest Fisher, were beginning to recognize and articulate, that is how housing markets function. There are direct chains of causality, for example from tenants to landlords to lenders. There is also complexity in the way that individuals play multiple roles so that private investors are themselves tenants, homeowners, and/or landlords. That is always true. But the Depression raised the stakes and brought a sea-change in the role of governments at all levels. Local governments became indispensable, taxing property owners while providing relief directly to tenants, indirectly to landlords, and sometimes to desperate homeowners. Including all of these agents completes the picture and gives us a better idea of what was going on.

To that end, case studies are indispensable. As Rose (Reference Rose2021, Reference Rose2022) has pointed out in his study of Depression-era Baltimore, much relevant evidence, notably land registry and property assessment records, are usually only available locally. More importantly, especially in the 1930s, housing markets were local, more so than for any other consumer good. Unlike other commodities, housing was immobile. Most producers – whether builders or landlords – were locally-based, as were lenders. Those who worked in a city lived there, or in adjacent suburbs, and vice versa. As a result, market conditions varied widely. Evidence is more complete for the United States than for other countries and serves to make the point (Harris Reference Harris2023a). There, in 1934 in the depths of the Depression, annual foreclosure rates on owner-occupied homes varied more than tenfold, from 0.6/1000 loans in Richmond, Virginia to 7.4/1000 percent in Wichita, Kansas (Wickens Reference Wickens1937: Table 36). The employment base and history of each place shaped its occupational profile, together with the mix of housing types, property owners, and local investors. For example, the share of the mortgage market held by private investors and lenders ranged from 4 percent in Worcester, MA, to 64 percent in Butte, Montana (Wickens Reference Wickens1941: Table D17). These and other circumstances together shaped market dynamics, along with the health and outlook of the municipality. In 1933, the incidence of property tax delinquency extended from the trivial, in Providence, Rhode Island (2.0 percent), to the crippling, in Atlantic City, New Jersey (63.6 percent) (Bird Reference Bird1936: 343). Recognizing how local housing markets were, and the tight interdependence of local agents, the present study focusses on the experience of one city, Hamilton, Ontario.

As a Canadian city, Hamilton was in one respect unusual, and in two respects quite different from any American counterpart. Private investors played a relatively large role in the mortgage scene, while lending institutions remained sound and federal initiatives had minimal impact on the market until the 1940s. But if in those respects it was distinctively Canadian, Hamilton shared fundamental characteristics with all North American cities: its residents were profoundly affected by the Depression; overwhelmingly, its housing stock was privately owned, with residents consisting of a roughly equal mix of homeowners and tenants; many owners relied on mortgage credit; and, while depending on property tax revenues, the municipality came under growing pressure to provide relief. In the United States during the Depression, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) used Peoria, Ill., an urban area of 150,000 that was similar in size to Hamilton, to refine its new methods of housing market analysis (U.S.F.H.A. 1935). Convenient in size, in the work of Doucet and Weaver (Reference Doucet and Weaver1991) Hamilton has already served a similar purpose, a precedent on which the present paper builds. In outline, if not in detail, its experience was symptomatic.

The Canadian scene comparedFootnote 2

The main symptoms are familiar. The Canadian economy was almost as devastated by the Depression as that of the United States, more so than Australia and far more than Britain or most of Europe. In three years, 1929–32, the unemployment rate catapulted from 4.2 to 26.0 percent (Struthers Reference Struthers1984: 215). Meanwhile, the national income fell to 55 percent of its level in 1929, compared with 48 percent for the United States, and by 1937 the level in both countries had barely recovered to the mid-80s level (Safarian Reference Safarian2009: 98). The construction industry was devastated dropping by 83 percent, 1928–33, causing massive unemployment (Greenway Reference Greenway1942: 508). Building was unprofitable. Firestone (Reference Firestone1951: 101–02) debates how far house prices fell between 1929 and 1933, suggesting 21 percent but adding that “one study” estimated 37 percent. A similar range of estimates applies to the United States, although Rose has suggested that these may be underestimates (Fishback and Kollman Reference Fishback, Kollman, White, Snowden and Fishback2014: 229; Gjerstad and Smith Reference Gjerstad, Smith, White, Snowden and Fishback2014: 96; Rose Reference Rose2022). Not surprisingly, rents followed, ranging between a decline of 24 percent (1930–34) in Canada and 31 percent (1929–33) in its southern neighbor (Greenway Reference Greenway1942: 508; Gjerstad and Smith Reference Gjerstad, Smith, White, Snowden and Fishback2014: 97). In its essentials, there was a shared continental experience. It follows that, although there is no Canadian evidence on Depression-era foreclosures, rates there should be similar to those south of the border.

Owners and investors followed a typical mix of strategies. Landlords, who owned most residential properties, lowered rents, but it hurt. By 1932, for example, Hamilton tenants were bargaining; encouraged by agents, owners of houses and apartments were luring them “from one building to another,” promising a free month’s rent (“House renting …” 1932). The result was predictable. In 1935, a Vancouver lobby group for the real estate industry commented that “for the last five years the landlord has had a terrible time: few buildings, if any, have paid anything worth while” [sic] (Vancouver Real Estate Exchange Ltd. Reference Horn1935: 201). Things were little better by 1938. Evictions had declined, but a decade of “small incomes received from the properties” had compelled landlords to scrimp on maintenance, resulting in poor conditions (“Bad housing conditions …” 1938).

A few landlords managed well. Robert Sweeney (Reference Sweeny2021) has shown that in Montreal a few rentiers had accumulated property portfolios over generations, often through marriage. With capital, they may have thrived by buying up buildings at fire sale prices. But rentiers were untypical. Richard Dennis (Reference Dennis1995) – who underlines how little historians know about landlordism – suggests that smaller ones were hard hit, being least able to afford evictions. Often, their incomes were little better than that of their tenants. That mattered because small landlords were the norm, as they remained after 1945 (Doucet and Weaver Reference Doucet and Weaver1991: 348; Mallach Reference Mallach2007). Many, including resident landlords, owned just one property. Sometimes this was inadvertent. When a Hamilton homeowner defaulted, the buyer took up residency but let his family stay on as basement tenants (Broadfoot Reference Broadfoot1997: 9–10). More commonly, and notably in Montreal with its extensive stock of plexes, becoming a small landlord was strategic (Canada 1935: 26). As the Montreal architect Percy Nobbs commented, “… at the beginning of the Depression the housing of the unemployed was done by the petit propriétaire” (ibid.: 42). It did not help that vacancies had more than doubled. In Toronto, the rate in single-family dwellings rose from 1.6 percent in 1930 to 3.1 percent three years later; meanwhile, those in apartments and duplexes jumped from 9.4 percent to 15.8 percent (Carver Reference Carver1946: Table X). Hamilton’s slightly higher overall rate rose in lockstep, from 7 percent in 1929 to 16 percent in 1934, a level like that in many American cities (Doucet and Weaver Reference Doucet and Weaver1991: 400–01).

Reluctant to lose tenants, landlords made other concessions. Revisiting their classic study of Middletown, the Lynds (1937: 190) note “the lenience of many landlords [was] in part dictated by their desire to have their properties occupied by trusted tenants rather than standing idle.” The threat of eviction was often just a bargaining tool. In Chicago, Edith Abbott (Reference Abbott1936: 430) reports that “frequently” the landlord “waits a while,” hoping the tenant would pay up. Doucet and Weaver (Reference Doucet and Weaver1984: 257) found that this tactic had been advocated by a Hamilton property agency during the recession of the 1890s. Indeed, the agency’s records indicate that barely half of the notices served resulted in evictions (Doucet and Weaver Reference Doucet and Weaver1991: 374). Hamilton landlords adopted the same tactics during the Depression. A retired worker interviewed by Peter Archibald (Reference Archibald1996: 372) recalled that eviction “wasn’t done very often.” As the Lynds (Reference Lynd and Lynd1936: 115n25) observed, during the Depression, “grocers … and the landlords of Middletown have borne a heavy burden of bad debts and slow payments.”

Landlords feared bad optics, coupled with popular resistance. Lester Chandler (Reference Chandler1970: 52) has described them as “one of the least loved economic classes in America”; their image was no better in Canada. It was easy to mobilize crowds to resist evictions, a tactic employed by communist activists. Every city offers examples, including Cleveland and Toronto’s East York (Schultz Reference Schultz1975; Kerr, Reference Kerr2011: 89–93). In Hamilton, “a crowd of angry neighbors” gathered in April 1933 to stop bailiffs ejecting the Reape family from 216 Belmont; a year later, when landlords were being criticized for “hard-heartedness” from “several quarters,” a “family was moved back into the building they had been evicted from by incensed neighbors” (“Angry crowd …” 1933; “Two fatally hurt …”, 1934). Even if the eviction was successful, with his reputation tarnished, the landlord faced a challenge in finding another tenant.

As they lowered rents and dealt with vacancies, mortgaged landlords found it harder to pay taxes and satisfy lenders. In the United States, a Financial Survey in 1934 showed that the owners of rental properties were especially likely to be in arrears (45.7 versus 41.9 percent) (Wickens Reference Wickens1941: Table D44). The only evidence on foreclosures of rental properties is local, the best being the Cleveland Real Property Inventory. There, between 1927 and 1937, the foreclosure rate on rental homes (12.5 percent) was higher than for those that were owner-occupied (10.9 percent), and much higher on large apartment buildings (43.1 percent) (U.S. Federal Home Loan Bank Board, n.d.: 13). There is no comparable Canadian evidence, but there is no reason to believe that landlords there fared better than their southern neighbors. As the planner, Noulan Couchon, observed about Montreal, “a great many” petit propriétaires “had lost their homes” He then paused, adding: “[a]s a matter of fact, they have been losing them by the thousands” (Canada 1935: 26. See also Choko Reference Choko1980: 114).

So, of course, had homeowners. Many Canadians, no less than Americans, aspired to own their own home. By 1930, a similar proportion of urban residents had achieved that goal – 46 and 44 percent, respectively (Harris and Hamnett Reference Harris and Hamnett1987). Fewer Canadian homeowners had mortgages, 31 versus 45 percent, mostly because Canada had fewer large cities where homes were least affordable (Harris and Ragonetti Reference Harris and Ragonetti1998). But those in debt probably struggled just as much. ‘Probably’ because here, again, the American evidence is better, although not ideal. National data for the United States indicate that the Depression caused annual foreclosures on non-farm properties to almost quadruple, rising steadily from 3.6/1000 loans in 1926 to 7.9 in 1930 and peaking at 13.3 in 1933 (Snowden Reference Snowden, Carter, Gartner, Haines, Olmstead, Sutch and Wright2006: Table Dc). This is helpful, but incomplete because it omits voluntary defaults, commonly in the form of quit claims. It is unclear how common these were. Local case studies yielded estimates ranging from 14 percent to 63 percent of all defaults (Mehr Reference Mehr1944: 56; Hoad Reference Hoad1942: 52). Nationally, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) reported 18 percent, but as a public agency, its experience was untypical (Harriss Reference Harriss1951: 3). All that can be said is that the rate of default was higher than foreclosure statistics suggest.

In Canada, Baskerville (Reference Baskerville2008: 287) has shown that in Victoria, B.C. foreclosures exploded during the 1890s recession, but no comparable evidence is available for 1930s. There are commentaries akin to what Couchon said about Montreal’s small landlords. In Vancouver, as noted, the Vancouver Real Estate Exchange bemoaned their fate. Two years later, in the city’s Better Housing scheme 30 percent of borrowers had defaulted and another 33 percent were in arrears (Wade Reference Wade1994: 52).Footnote 3 In Ontario, mortgage companies and local housing commissions reported that “large numbers of workingmen … must be substantially behind on their mortgage and interest payments” (Cassidy Reference Cassidy1932: 240). Indeed so. Around Toronto, Paterson (Reference Paterson1988: 218) found that in five subdivisions 8.9 percent of all mortgage loans defaulted between 1909 and 1941. Most were voluntary quit claims, which accords with the findings of a study of nineteenth-century rural Ontario (Gagan Reference Gagan and Armstrong1974: 151). Most of the defaults reported by Paterson surely happened during the 1930s. Ghent’s (Reference Ghent2011) evidence for New York suggests that most lenders were inflexible, but a Canadian observer reckoned that institutional lenders “tried to ‘nurse’ their urban and rural debtors” (Drummond Reference Drummond1987: 335). After all, the market was depressed. Hamilton’s Housing Commission is an extreme case: by 1940, more than two-thirds of its borrowers were in default (Doucet and Weaver Reference Doucet and Weaver1991: 292). The net effect during the thirties was to bring down the Canadian rate of urban homeownership by five points (Harris and Hamnett Reference Harris and Hamnett1987).

Under pressure from mortgaged property owners, and like many American states (Wheelock Reference Wheelock2008), Canadian provinces introduced moratoria. Provisions varied, but the core idea was to restrict foreclosures for a specific period. In Ontario, by 1932 there was “strong public demand,” and a Relief Act was passed in March (Cassidy Reference Cassidy1932: 119; Ontario 1932; Doucet and Weaver Reference Doucet and Weaver1991: 290). Borrowers in arrears on repayment of principal could appeal to stay proceedings of foreclosure. This was not a slam dunk. John Falconbridge (Reference Falconbridge1942: 836), in the definitive Canadian legal text on mortgages in this period, notes that judges had “absolute discretion,” one consideration being whether “the mortgagee’s security is … imperiled.” Moreover, arrears on interest and taxes were not covered, so public pressure continued. In January 1933, for example, a deputation of Hamilton “property-holders,” headed by the local member of the provincial parliament, lobbied for a broadening and extension (“Three deputations …” 1933). This was granted, and a revised moratorium included all types of arrears. Despite appeals from institutional lenders, this legislation was renewed until 1946.Footnote 4 It surely had some impact. Beforehand, the annual mobility rate of homeowners in Toronto’s suburbs was 12 percent (Harris Reference Harris1996: 239, 247). In the following two years, it dropped to 8.3 and then 5.4 percent. Fewer owners were being compelled to move. But this was probably only a short-term effect and was a mixed blessing: some homeowners got a temporary reprieve, but lenders became wary.

Only borrowers risked default, but all property owners paid taxes, and their arrears were rising. Across the United States, year-end tax delinquencies jumped from 10 percent in 1930 to 26 percent in 1933 (Bird Reference Bird1936: 339). There are no national data for Canada, but one clue is that Montreal’s tax arrears reached 43 percent of the city’s annual budget (Tillotson Reference Tillotson2017: 103). After three years, municipalities were required to take possession and list the property in a scheduled tax sale, “unless definitely instructed to the contrary” (“Official acquitted …” 1934). In the City of York (a Toronto suburb), “when the Depression struck, a large number of homeowners lost their properties, either to the mortgage holder (usually an individual …) or as a result of their inability to pay property taxes to the township” (City of York 1987: 141). But, as in the United States, property owners resisted (Beito Reference Beito1989; Tillotson Reference Tillotson2017). Like landlords and lenders, and for similar reasons, municipalities relented. As David Beito (Reference Beito1989: 8) observes, at tax sales “buyers could nowhere be found.” In many ways, then, during the Depression, the Canadian experience paralleled that of the United States.

But there were differences, primarily concerning mortgage credit. In the United States, the financial system buckled. Many banks and Savings and Loans went under, and the federal government took major steps to strengthen the survivors (Fish Reference Fish and Fish1979; Schwartz Reference Schwartz2021; White Snowden and Fishback 2014). Through the HOLC it refinanced over a million homes in imminent danger of default. In contrast, no major financial institution in Canada collapsed, and the federal government took no steps to ensure stability (Bacher Reference Bacher1993). Nor did it refinance mortgages. Even the Dominion Housing Act of 1935, which signaled the arrival of the federal government as a permanent presence on the housing scene, was a pale imitation of the U.S. National Housing Act of 1934, which established the Federal Housing Administration. Throughout the Depression, Canadian mortgage arrangements were largely unaltered.

They were still dominated by private, individual lenders. In the United States, individuals provided more loans than any type of institutional lender; in Canada, they loomed larger than all institutions combined (Harris and Ragonetti Reference Harris and Ragonetti1998; Doucet and Weaver Reference Doucet and Weaver1991: 283). The reasons were complex. Banks were prohibited from lending on real estate while building and loans, always less important than their American counterparts, had relied on British capital, which dried up after 1918. For decades, mortgages had been a popular investment for men and women with spare capital, partly because they were seen to be safe (Fell Reference Fell and Parkinson1940: 129; c.f. Baskerville Reference Baskerville2008). When the Depression struck, many private lenders adopted the same flexible strategy as the institutions, often because they knew the borrower personally. From Fairview, Nova Scotia, for example, in July 1932 a Miss Glean wrote that her family, currently seven months in arrears, “would have been swept out a month ago” except that Mr. Eastman “took pity on us and he is trying to give me a chance” (Grayson and Bliss Reference Grayson and Bliss1971: 32). Whether the judgment of such lenders matched that of loan officials at the institutions is an open question. Insofar as it is indicated by rates of mortgage default, as they varied between homeowners and landlords, it is an issue that the case study of Hamilton can address.

Hamilton’s owners and lenders in context

Hamilton highlights some of the housing issues in play during the Depression while exemplifying others. Although ranking seventh in size among Canadian cities, it was the nation’s pre-eminent industrial center (Richards Reference Richards1939). As such, after 1929 most employers, and their male workers, were unusually hard hit. In 1929, the purchasing power of the city’s workers was in the middle of the Canadian pack (Greenway Reference Greenway1942: 466). But work soon dried up. By 1930–31, those in leading blue-collar occupations found themselves unemployed for large parts of the year: iron and metal workers worked only 35 weeks, those in skilled trades rather less, and laborers 29 weeks (Archibald Reference Archibald1998: 157). The declining trend continued, in some cases precipitously, and wages were cut (Archibald Reference Archibald1992: 9). The only bright light was that the textile and clothing industries remained active. Numerous families came to rely on the modest income earned by women, many of whom also took in lodgers (Harris Reference Harris1994; Weaver Reference Weaver1982: 35). This challenged a domestic culture that emphasized the role of men as family breadwinners (Christie Reference Christie2000).

Even by the standards of the time, there was unusual distress. In two years, 1931–33, the number of families on relief jumped from 2209 to 8160, at which point the city created a Public Welfare Department (Archibald Reference Archibald1992: 10; Weaver Reference Weaver1982: 135). At the peak, a quarter of all households depended on public support. Across Ontario, this was unusually bad news. (Conditions out west were worse still.) Information provided by Cassidy (Reference Cassidy1932: 45) for individuals, as opposed to families, makes the point. In April 1930, only 0.8 percent of Hamilton’s population was on relief, compared with 1.5 percent in Toronto. But within 24 months Hamilton’s share had jumped to 14.3 percent, overtaking Toronto’s 9.9 percent. No wonder many people left town, riding the rods, or returning to the land. During the 1930s, Hamilton’s population, 156,000 in 1931, fell by over two thousand. Here, quintessentially, was a city in trouble.

The other way in which Hamilton stands out, even in Canada, is in the prominence of individual investors. Nation-wide, the share of the so-called “personal sector” in non-farm mortgage debt ranged between 40 and 50 percent during the 1930s (Harris and Ragonetti Reference Harris and Ragonetti1998). This figure is approximate. As a residual category that includes non-profits as well as non-financial businesses, it overstates the significance of private individuals. Conversely, it does not include equitable mortgages. Following British precedent, to this day Canadian law recognizes such arrangements, whereby the borrower places the title deeds with the lender until a certain proportion – sometimes all – of the loan has been repaid; “no actual mortgage document … has been executed” (Woodard Reference Woodard1959: 52; Falconbridge Reference Falconbridge1942: 69–84). There is no way of knowing how common these were, or who provided them. However, their prominence in a contemporary legal text suggests that they were quite frequently employed, while their informal character suggests they were most common where borrower and lender knew each other.

Regardless, individuals clearly played a smaller role nationally than in Hamilton. There, through the first decades of the twentieth century, they made nine out of ten first mortgage loans, dropping slightly to four-fifths in 1931 and then just under three-quarters in 1941 (Harris and Ragonetti Reference Harris and Ragonetti1998). A subsample described later indicates that a third were women, and among the men, there were a disproportionate number of the self-employed and professionals (Harris Reference Harris2023b). The institutional sector was correspondingly marginal: in 1931, insurance companies held just over 7 percent of loans, with loan and trust companies making up most of the balance between 3 and 4 percent each. It is hard to imagine a better place to explore the impact of the private lender.

In other respects, Hamilton was more typical. Although only fifty miles from Toronto, its housing market was distinct. Analyzing its housing scene in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Doucet and Weaver (Reference Doucet and Weaver1991: 364–65) conclude that “the rental shelter business was extremely localized.” Between a quarter and a third of all landlords, most of whom owned only one or two properties, not only lived in the same city as their tenants but on the same block, or even the same house. Lenders were just as local. The subsample discussed later shows that through the 1930s more than nine out of ten lived in Hamilton or its suburbs. Typically, too, Hamilton was a city of detached single-family dwellings, albeit ones often occupied by tenants. A small wave of apartment construction before WWI had been followed by a larger one after 1918, becoming a “mania” in the late 1920s (Doucet and Weaver Reference Doucet and Weaver1991: 391). By the stock market crash, then, the city had a serviceable mix of housing types as well as tenures. Serviceable in the good times. Given what was happening in the labor market, however, rents, and probably prices, tanked while owners struggled.

Being a landlord in Hamilton in the early 1930s was a torment. Tenants were hard to find. Between 1929 and 1934, the vacancy rate rose from 7 percent to 16 percent, in line with the North American trend (ibid.: 401). In 1933, a relief official commented that “landlords are certainly worse off than a year ago” (“Owners prefer …” 1933). Desperate, they lowered rents by about 25 percent (Archibald Reference Archibald1992: 11). A simple calculation suggests that on average their revenues fell by 32 percent. Meanwhile, taxes and, for borrowers, mortgage payments were unaltered. Landlords became defensive. When her eviction of a tenant made headlines, one landlady made her case: “we have to get our rent or we won’t be able to pay our taxes and then we won’t have a house to rent,” adding, “landlords and landladies are not necessarily the villains of the piece” (“Says eviction last resort …” 1934).

The occasional tenant agreed. After one family was evicted, neighbors looked after the mother and daughter while the father and a “small boy” slept outside to guard their furniture. Even so, the mother conceded that “you can’t blame the landlord” (“Printer injured,” 1934). But she was unusual. Most tenants, neighbors, and activists were militant in their resistance, so that by 1936 “only one firm was willing to carry out evictions” (“Evictions in Hamilton …” 1936). It is clear where popular sympathies lay. The newspapers reported many evictions, but few cases where landlords went under. It took a letter to the Toronto Globe for one Hamilton landlord to bemoan the way he lost both an “apartment house and business property” (“Ask lower interest …” 1935).

Homeowners were also in great trouble. The defaulting homeowner who was allowed to move into the basement was a typical case. Steve Metarski, a Polish immigrant and sub-contractor, bought a home in the 1920s (Broadfoot Reference Broadfoot1997: 9–10). After work dried up, the house went to a bankruptcy auction, but he was allowed to keep possession and try to maintain payments. This proved impossible. The challenges of homeowners received more coverage than those of landlords. In 1934, the Hamilton Herald – itself soon to go under – told the story of Samuel George, 49, a war veteran, British immigrant, taxi driver, one-time bricklayer, “sturdy citizen,” and father of two, who was in imminent danger of default (“Taximan says …” 1934). And desperate times called for desperate measures. An Italian-Canadian, Mike Pokotelli, lied in order to get relief, passing the proceeds to his brother-in-law to help cover a mortgage (“Used money …” 1933). The net effect was that homeownership fell: according to the assessment record sample, from 54 percent in 1931 to 46 percent in 1941.Footnote 5 This average disguises great variation. In Hamilton, typically, it was the young and single who were laid off first (Heron Reference Heron2015: 108). In a cohort analysis, Doucet and Weaver (Reference Doucet and Weaver1991: 312) have shown that during the 1920s homeownership in the 25–34 year-old group fell from 36 percent to 24 percent. The following decade it fell further, to 14 percent. The trajectory of 34–44 year-olds – 53–44 to 27 percent – was even worse. Singles and younger families were kept out of the homeowner market, while many of those who had got their foot on the ladder in the 1920s were in trouble.

Residents of all sorts sought assistance wherever they could find it. Tenants were the first to get help. By 1932, private organizations, notably Hamilton’s Central Bureau of Family Welfare, were disbursing “large sums for rent” and had intervened to “persuade landlords to carry their tenants a little longer” (Cassidy Reference Cassidy1932: 217, 229–31). Although payment was often made directly to the landlord, many of the latter became wary “for they fear that they will be left to carry unemployed tenants in later months” (ibid.: 245). Agencies had limited funds, offered only stopgap assistance, and ended up covering barely one-seventh of all relief costs (Weaver Reference Weaver1982: 135). As the Depression deepened, tenants turned to the city, and by 1932 Hamilton, like other Ontario municipalities, was “finding it necessary to assume greater responsibility for paying rent …” (Cassidy Reference Cassidy1932: 213). It tapped the province, which eventually agreed to reduce the city’s share of relief costs to one-third. After wrangling, a policy emerged whereby tenants facing eviction could qualify for a monthly amount that equaled 150 percent of the landlord’s annual charge for property tax and water, divided by twelve (Weaver Reference Weaver1982: 135). Payment was made to the landlord if he or she accepted the arrangement. This always involved a substantial reduction in rent, notably in Hamilton where by 1936 the rent allowance of $9/month was among the lowest in the province (Struthers Reference Struthers1984: Appendix IV).

For landlords, this was a better, more permanent, arrangement than that offered by social agencies, but it left many in trouble. They fought back. In May 1933, veterans’ associations reported over a hundred cases where landlords refused to accept rent vouchers and were taking steps to evict; the city’s Controller “said it looked as though landlords and real estate agents were taking concerted action to try to force the payment of higher rent relief” (“Government willing …” 1933). The city stood firm, however, and eventually all but one landlord was “lenient when appealed to” (“Only one relief tenant …” 1933). This did nothing for those in debt, many being in desperate straits. That same year, a provincial survey found that fully 98 percent of relief payments to tenants went to municipalities to cover landlords’ back taxes, something which many municipalities, including Hamilton, required (Ontario, 1934: 52). Hamilton landlords appealed this, too, and were told that, at the discretion of the Welfare Commissioner, a landlord might be allowed to keep one in three rent relief payments for himself (“Landlords get part of rent” 1934). But evidently, the Commissioner thought this to be “a rare thing.”

Once tenants were receiving reliable, if meager, assistance, homeowners pressed their case. By summer of 1933, about 1,500 were on relief (“Relief for home owners” 1933). City Council agreed in principle that they should receive assistance equivalent to that offered to tenants, but the decision lay with the newly established Relief Board. The Board was unwilling to act without provincial support, and so regularly sought guidance. In July, at the request of Hamilton’s Welfare Commissioner, the province explained that for a homeowner on relief, it would only help with property taxes if the municipality “threatens and takes action” or the lender calls in the bailiffs (“Veteran teachers …” 1933). Subsequent clarifications noted that support was only available to those who had been denied protection under Ontario’s moratorium, and where the owner was at least 12 months in tax arrears (“Freed at Hamilton …” 1933; “Home owners are disappointed” 1933). The province emphasized that the goal of relief was to prevent eviction not to protect the owner’s equity, unless the family “might be in danger of not having any place to sleep” (“He interprets …” 1934). In practice, because courts favored mortgaged owners with substantial equity, only those who were deep in debt received help (“Owners of homes …” 1934: 1). Even so, despite lobbying from the newly-formed Home Owners’ Association, the Welfare Board was slow to act and conservative in its interpretation of the guidelines. By November 1935 it had grown even more parsimonious. It was requiring that twenty-five unmortgaged homeowners take out mortgages, instead of going on relief. Under pressure it backtracked, but then asked those applicants to give mortgages to the city to cover their relief payments. The city’s downfall was that it refused to reimburse the province for its share of those payments. It was nixed by the provincial Ministry of Welfare (“Won’t oblige …” 1935; “Scheme to mortgage home-owners…” 1935).

Throughout this wrangling, there were regular reports of “hundreds of home owners” being “confronted … by foreclosure proceedings” (“Welfare Board is attacked by owners,” 1933; c.f. “Board is tied …” 1933). When these were carried through, neighbors and activists sometimes organized resistance. In June 1934, for example, when bailiffs evicted the Forostians, who moved into a tent, “feeling against the mortgagee ran high” (“Evict owner …” 1934). Probably because their son was associated with the Young Communist League, a Communist candidate in the forthcoming civic election delivered a speech from the front steps of the house. But such actions were less common than with tenants. Amidst growing need and continuing uncertainty, tenants and homeowners competed for public attention and city relief. The civic election in fall of 1933 highlighted mutual resentments, creating the highest turnout on record – double the rate of 1929 (Archibald Reference Archibald1992: 17, 20).

The twists and turns of the City and the Welfare Board were rooted in the City’s dire finances. Tax arrears had been growing steadily since 1930. A prepayment plan was introduced in January 1933, which offered a 4.5 percent discount, and within a year 800 property owners had taken advantage (“Dundas teachers …” 1934). By 1935, however, there were more than three times as many that were more than three years in arrears (“Mayor questions …” 1935). In February 1934 the Tax Collector was asked why collections had “fallen so far below those of many other Canadian cities” (“When bailiff called off” 1934). He explained that, following provincial instruction, tax sales, and the use of bailiffs, had been suspended for two years. This had probably made little difference. Later that year, when the province allowed a new sale, of the 1000 properties on the block only 13 were sold. The city’s treasurer argued that this was a poor measure of success, suggesting instead that “the value of tax sales lay in the incentive they provide delinquent property owners to … pay up their arrears” (Junior high school …” 1935).

He was probably right, just as comparable threats of foreclosure from lenders and of eviction from landlords were sometimes having the desired effect. The Depression had forced tenants, homeowners, landlords, lenders, and the city itself into making finely-modulated calculations about how much leeway they might be allowed, and how far they could go in their financial negotiations. It was a complicated collective dance, not least because both circumstances and rules were changing all the time. To understand the main results of this dance – who lost their property, to whom, and in what manner – historical researchers need to dig into the local records that tell us who owned, who owed what to whom, and what their respective status was as residents and taxpayers.

Methodology

The key records are the plan abstract books in the land registry, the annual property assessments, and, for supplementary purposes, city directories. They were tapped to reconstruct patterns and changes in property ownership and mortgage financing in Hamilton throughout the first half of the twentieth century. Accordingly, a longitudinal data file was created, including some information from other decades not reported here.

Together, these sources provide an unparalleled picture of the mortgage scene. Abstract books summarize key information about the legal ownership of land parcels, together with details about the amount, source, and terms of mortgages (Hagopian Reference Hagopian1995). They also show whether, and how, those encumbrances were removed. Inconveniently, however, they are organized by registered plan, not address. It was impossible to construct a random sample directly from this source, above all because registered properties often do not correspond to individual dwelling units, notably with apartment buildings. Instead, an initial 0.1 percent sample of dwelling units was drawn from the City of Hamilton’s assessment records for 1951 by counting every thousandth residential unit listed. This yielded 114 units. Assisted by Walter Jaksic in the Hamilton-Wentworth Registry Office, a graduate student, Doris Forrester determined in which registered plan each unit fell. These units were seeds from which she and two research assistants grew clusters, each of 49 additional units, usually by proceeding clockwise within the plan, starting from the original. In some cases, units had to be added from adjacent plans. City directories confirmed that all units were residential. This yielded a 5 percent sample of 5700 residential units. For each, mortgage information was recorded. In the case of defaults, the voluntary and involuntary options, four in total, were recorded. This information was then linked to property assessments, which indicated tenure, dwelling type, and assessed value. From the land registry, the legal history of each property was tracked from 1901. With more effort, and for each unit, assessment records yielded tenure and dwelling type for each census year, 1901–51.Footnote 6 This is the core database.

Supplementary databases addressed specific questions, including those pertaining to private lenders and the timing of default. A 25 percent subsample was constructed of properties that were mortgaged to private individuals. For three years – 1931, 1941, and 1951 – information was gathered on the name, occupation, address of lender, terms of the mortgage, and when the mortgage was taken out. For this subsample, city directories were used to determine the tenure status of the lenders and to establish the household status of those identified as married women. Some findings are reported here. Independently, another subsample was taken of all properties that were mortgaged in 1931 and which subsequently experienced defaults. For these properties, information was recorded on the name, occupation, address of lender, the terms of the mortgage, when it was taken out, and when default occurred.

Results

Based on these sample data, it was possible to document for the first time for any North American – or indeed any city anywhere – the changing timing, incidence, and form of mortgage defaults during the Depression, as well as their variations by tenure and lender type. ‘Default’, not ‘foreclosure’ is the key word. As noted earlier, defaults could occur in more than one way. The basic distinction is between voluntary, where the borrower simply relinquishes the property, and involuntary, where the lender takes the lead. It is useful to be clear about what each entailed.

In the national U.S. data, “foreclosure” is used in a broad sense to include the involuntary “power of sale” as well as true foreclosures, which go through the courts (Snowden Reference Snowden, Carter, Gartner, Haines, Olmstead, Sutch and Wright2006). Both were options in Ontario. Foreclosure was expensive because lenders had to go through the courts. Judges favored borrowers who were still paying interest and taxes (Woodard Reference Woodard1959: 28). And the procedure could take six months if, as was common, the borrower requested time to pay arrears. Power of sale usually took one month, with no legal uncertainty, and was cheaper. Falconbridge (Reference Falconbridge1942: 662) observed that it was “a simpler and more expeditious mode of getting rid of the mortgagor's equity of redemption and of realizing the mortgage debt.” (It still is.) Hence, when available in the United States, it was often preferred (Russell and Bridewell Reference Russell and Bridewell1938). In Ontario, it usually had to be specified as an option in the mortgage contract, and lawyers were skeptical, perhaps because it reduced their business (e.g. Mikel Reference Mikel1933). However, this option was routinely included in Hamilton mortgages (Doucet and Weaver Reference Doucet and Weaver1991: 251). For example, in 1925 Robert Duncan, a watchman, obtained a loan for $3,200 from Hugh Thompson which noted that power of sale could be enforced at one month’s notice. The mortgage ran for three years, with half-yearly installments of interest only.Footnote 7

For lenders, the advantage of going to court was the possibility of getting a deficiency judgment: if the defaulted property was worth less than the mortgage, the lender could claim the balance owing. This matters when property values have tanked and mortgage ratios are high. After 1929, values fell a lot, but the conventional wisdom is that first mortgages rarely exceeded 50 percent. However, a recent study of Baltimore indicates that many borrowers also held junior mortgages and faced high loan-to-value ratios (Rose Reference Rose2022). Indeed, one in three were underwater by 1932. In Ontario, contemporary commentary indicates that fewer borrowers were as deeply in debt and that fewer lenders needed recourse. A rare exception came when the lender on a slum property in Toronto declined a quit claim because of substantial back taxes on a rental property that had been allowed to deteriorate (“Mayor says bailiffs …” 1938). For most lenders, the ideal was a voluntary default.Footnote 8 In America, the U.S. federal agencies disagreed about whether to encourage this. The HOLC favored them “whenever possible,” because cheap and quick (Harriss Reference Harriss1951: 82), but the Federal Housing Administration disapproved because they could be challenged in court (Bovard Reference Bovard1936). Judges knew that lenders, in a position of power, might pressure debtors to be compliant. Lenders could point out that foreclosure would ruin a borrower’s credit. Occasional reports indicate that requests, and sometimes pressure, were exerted. Some borrowers resisted – it is impossible to say how many. In 1933, for example, the City of Toronto repeatedly leaned on an owner who was behind on taxes as well as mortgage payments. The owner resisted, declaring that “he had no intention of signing a quit claim deed” … “I intend to protect my equity and my life savings” (“Occupant resists” 1933).

More commonly, borrowers acquiesced or volunteered to negotiate. In 1937, a Toronto Globe and Mail correspondent suggested that, if a borrower offered a quit claim, he might receive $50–100 from the lender, saving time and legal fees (Farmer Reference Farmer1937). This was implausible. A more likely scenario was reported in the Toronto Daily Star in 1933 when a lawyer offered a borrower $5 (“Urges 100 P.C. Moratorium” 1933). Even this might have been generous. Some settlements recorded in Hamilton, such as the one that Rich Bigrigg, a carpenter, offered Alice Lawson, married woman, in 1938, involved a nominal $1.Footnote 9 Releasing the equity of redemption was another option (Falconbridge Reference Falconbridge1942: 54–55). Here, too, negotiation happened, with variable results. In August 1935 Fred Taylor, gentleman, gave $100 to Edith Stephens, recently widowed, in return for her release of equity on a $1200 mortgage taken out in 1924. Judging from other cases, however, such as Letitia Hamilton’s payment of $1 to William Bradley in March 1938, a more modest sum was the norm. The sample size is small, however. All that can be said with certainty is that “inducements” were common and sometimes substantial, while many probably went unrecorded. Mutual advantage made them worthwhile.

Newspaper accounts confirm that many Hamilton homeowners voluntarily gave up ownership. Late in 1931, while reporting that annual foreclosures had dropped slightly, the Hamilton Herald noted that “many” problems had been arranged in other ways, either with arrears being paid up or by “settlement without foreclosure” (“Fewer residents …” 1931). An example made headlines. A Mrs. Hempstead, realizing she could not maintain mortgage payments, let go of the property, the lender allowing her family to stay on as tenants (“Mrs. Hempstead” 1934). This was probably quite common given that lenders, in their new role as landlords, might otherwise have had difficulty in finding a tenant. Indeed, this was sometimes specified as a possibility – though never a legal certainty – in mortgage contracts, although it is unclear how long such arrangements lasted. It appears that, except in purpose-built apartment buildings, rental contracts ran monthly, or even weekly (c.f. Day Reference Day1999: 158, 165). Moreover, many were verbal, therefore difficult to enforce (Stark Reference Stark1936). At any rate, Mrs. Hempstead did not plan to stay on. Her husband and eldest son had ridden the rods to Alberta, where they bought a farm and built a home. The Herald was raising funds to ship her, and her other eight children out west. Hardly a typical case. But the paper noted that “this” – apparently, any type of default – was the “‘via dolorosa’ of hundreds of worthy Hamilton families.”

In fact, land registry records show that voluntary defaults rivaled the involuntary forms through the 1920s and 1930s. Among the mortgages on single-family homes existing in 1921, and which subsequently defaulted, 48 percent of properties were freely released by borrowers, usually through quit claims (Table 1). The equivalent proportion for mortgages existing in 1931, actually rose, slightly, during the 1930s, to 52 percent, before falling to 42 percent in the 1940s for mortgages existing in 1941.

Table 1. Types of mortgage default, Hamilton, Ontario, 1921–41

Source: 5 percent longitudinal sample of property assessments records, linked to land registry.

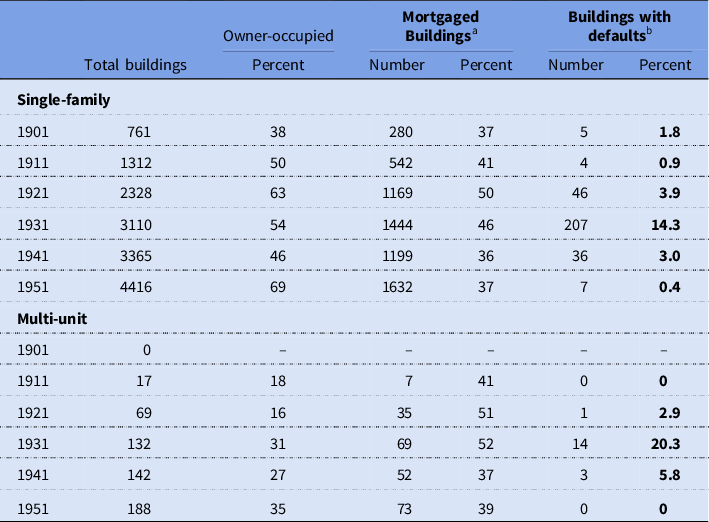

Those same records confirm that, as expected, overall rates of default were far greater during the Depression than in any other decade in the first half of the twentieth century. Rates were already higher in the 1920s than in the previous two decades: 3.9 percent of the single-family homes that had been mortgaged by, or in, 1921 later defaulted (Table 2). But the equivalent rate for 1931 more than tripled, to 14.3 percent. This turns out to be broadly similar to that of the United States as a whole.

Table 2. Mortgage defaults on single-family and multi-unit dwellings, Hamilton, Ontario, 1901–51

Source: 5 percent longitudinal sample of property assessment records, linked to land registry.

a Buildings with mortgages on the dates in question.

b Mortgages that existed in the years in question that were later defaulted.

Making the comparison requires ingenuity. Several steps are involved. First, considering only involuntary defaults, Hamilton’s rate for the 1930s was 6.9 percent which, divided by ten, yields an average annual rate of 6.9/1000. Step two involves averaging the available annual rates for the United States. This yields a figure of 9.8/1000.Footnote 10 However, this figure pertains to all non-farm properties. Fortunately, two plausible adjustments are possible. The first uses historical evidence on foreclosures sampled from lending institutions in the 1950s by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). It distinguished 1–4 family dwellings from all other properties, using samples of mortgages held by lending institutions (Morton Reference Morton1956). The fullest information on mortgages taken out in the 1920s, and mostly existing in 1931, is available for commercial banks. For them, the foreclosure rate for all properties (7.8 percent) was 6.4 percent higher than that for 1–4 family homes (7.3 percent).Footnote 11 Accordingly, the national rate for all types of property might plausibly be adjusted down to 9.2/1000. But evidence gathered by the Cleveland Property Inventory and later summarized by the Federal Home Loan Bank Board (n.d: 13) shows that foreclosure rates 1927–37 were higher on 2–4 family (14.1 percent) than on single-family homes (10.9 percent), yielding a weighted average for 1–4 family homes of 11.7 percent. Because this average is 6.8 percent higher than the rate for single-family homes, and assuming Cleveland’s experience was typical, the national rate for 1–4 homes may be adjusted downwards again to 8.6 percent. This figure is somewhat higher than the present estimate for Hamilton’s single-family properties. However, based on the meager evidence concerning voluntary defaults in the United States, it appears that in Hamilton a relatively high proportion of defaults took this form. If that was so, Hamilton’s experience was in the same ballpark as that of U.S. urban areas as a whole.

If, for many property owners, the 1930s were a bad time to be in debt, timing also mattered in another way. American research has established that the riskiest loans were those taken out just before the Depression. The NBER sample showed rates of default rising steadily from the early 1920s through the early 1930s, before declining (Morton Reference Morton1956: 100). One reason was that loans are always most vulnerable in the first few years, when the loan ratio is relatively high; those initiated in the late twenties had had little time to grow equity before the Depression hit. Another reason was that, as a contemporary text for appraisers warned, late in the decade an overheated market was encouraging corrupt practices, and poor judgment (Zangerle Reference Zangerle1927). Intriguingly, however, the experience of private lenders in Hamilton is subtly different (Table 3). Of the loans existing in 1931, 46 percent had been taken out since 1928, but these accounted for only 36 percent of defaults. The riskiest group was those made in 1925–27, with 17 percent of loans but 30 percent of defaults. The slight difference in timing may reflect a difference in risk assessment between institutional and private lenders, with the latter, dominant in Hamilton, becoming cautious as the decade wore on. Perhaps they were less caught up in the speculative frenzy of the late twenties.

Table 3. The origin date of residential mortgages held by individuals existing in 1931 and of those defaulting, Hamilton, Ontario

Sources: Columns 1 and 2: 25 percent subsample of original 5percent sample of property assessment records, linked to land registry. Columns 3 and 4: Properties in the original 5 percent sample for which reliable information could be obtained.

Note: Default rates, overall or for each time period, cannot be inferred from this evidence.

Timing mattered in another way. In terms of employment, incomes, rents, and prices, the Depression bottomed in 1933–34. That is also when foreclosures peaked across the United States. However, in Hamilton defaults peaked slightly later, in 1935–37, and a few persisted into the 1940s (Table 4). Again, the reason is unclear. Notably, the mix varied, with more voluntary defaults than foreclosures happening in the early thirties. This difference surely reflects the impact of the provincial moratorium, which began in May 1933, for this did not apply to voluntary defaults. During the moratorium some lenders may have encouraged borrowers to let go of their properties, thereby circumventing the law. For a different reason, a comparable, temporary dip in foreclosures is apparent in NBER’s statistics for U.S. lending institutions in 1933–34, which is when the refinancing activity of the HOLC was concentrated (Morton Reference Morton1956: 100). There, as in Hamilton, the timing of foreclosure indicates the impact of government policy.

Table 4. Timing of default on residential mortgages that existed in 1931, Hamilton, Ontario

Source: 5 percent longitudinal sample of property assessment records, linked to land registry.

But, as Henry Whipple Green, guiding force of the Cleveland Property Inventory, was the first to show, to speak of average rates of foreclosure, even within the category of residential real estate, was misleading. As noted earlier, the Cleveland RPI showed that rates of foreclosure were higher on multi-unit than on single-family buildings (U.S. Federal Housing Administration 1940: 122). This difference was probably attributable in part to differences in the experience of homeowners and landlords. Many researchers have shown that homeowners and landlords view their property differently (e.g. Mallach Reference Mallach2007). For homeowners, the dwelling may be a major repository of wealth and potential source of security, at least when owned outright, but it is also a home that embodies meaning. In contrast, landlords are likely to see it only as a source of income, or as a longer-term investment. The contrast is not sharp, especially for resident landlords and amateurs who own only one or two properties, but it is nonetheless real. With that in mind, it is reasonable to suppose that, under stress, strategies will differ, with homeowners hanging on as long as possible while, guided by financial considerations, smart landlords cut their losses. During the Depression, such a difference was often accentuated by the different pressures that the two groups faced. Families of homeowners were vulnerable to unemployment or reduced wages, but so were many amateur landlords, and these also faced reduced rents and vacancies. Such differences, in owners’ outlook and experience, surely help to explain contrasts between the foreclosure experience of one- and multi-family dwellings.

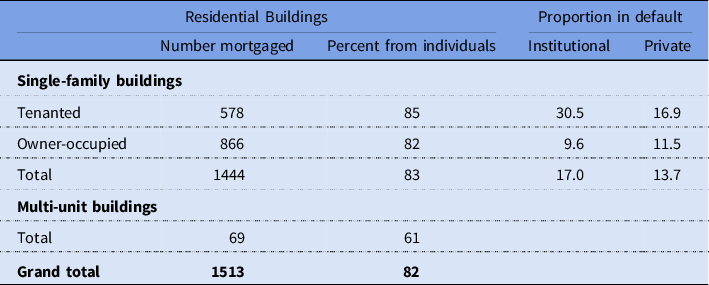

But the argument is speculative. Today, and even more during the Depression, many single-family homes are occupied by tenants. Doucet and Weaver (Reference Doucet and Weaver1991: 378–79) estimate that in Hamilton as late as 1941, almost half of all households, and 69 percent of all tenants, lived in rented houses. Conversely, units in many multi-unit buildings were occupied by their owners. The present evidence for Hamilton confirms that it is important to consider how defaults varied by tenure as well as by dwelling type. Not surprisingly, the incidence was higher in multi-unit (20.3 percent) than in single-family buildings (14.3 percent) (Table 5). But tenure mattered even more. Among single-family homes, the default rate on tenanted houses (19.0 percent) was almost as high as on multi-unit buildings, while the experience of owner-occupiers was markedly better (11.2 percent). This may be because homeowners were more likely to hang on. Among defaulting borrowers, a higher proportion of landlords (26 percent) than homeowners (17 percent) lost their properties by 1934, the pattern being reversed by the late 1930s (Table 4). This is consistent with the only comparable evidence, which again is for Cleveland. There, the timing of default was precisely modulated by dwelling size. The peak years for foreclosures of large apartments came in 1932 and 1935; those for 2- and 4-family dwellings in 1935–36, but only in 1937 for single-family homes (U.S. Federal Housing Administration 1940: 122).

Table 5. Tenure differences in mortgage defaults on single-family and multi-unit buildings, Hamilton, Ontario, 1931

Source: 5 percent longitudinal sample of property assessment records, linked to land registry.

If homeowners hung on longer, they did not necessarily wait until the lender acted. In fact, when they did default, they (58 percent) were more likely than landlords (46 percent) to do so voluntarily (Table 1). In Hamilton, this practice was inherited from the 1920s and continued into the 1940s. The greater willingness of distressed homeowners to release their properties, albeit after a longer struggle, seems paradoxical. Why not fight to the bitter end? Cost might have been a consideration, coupled with a fear or limited awareness of legal procedures. Homeowners might also have been more susceptible to pressure from lenders. Another factor might have been the attitude of the lenders themselves. Given that homeowners were generally viewed more favorably than landlords, lenders might have been more willing to cut them some slack. Certainly, that was the advice that a Hamilton-area lawyer was offering clients in the late 1930s (Doucet and Weaver Reference Doucet and Weaver1991: 288). Default, then, was more likely to happen when the borrower finally faced the inevitable, as Mrs. Hempstead did.

Indirect evidence suggests that in this regard the character of the lender might also have played a role. If, as noted earlier, the default rate on multi-unit dwellings was relatively high (20.3 percent), so was the extent to which their owners relied on institutions (31 percent) (Tables 1, and 6). The sample size is too small to disaggregate the default rate on apartment building by type of lender, but evidence for the more numerous single-family homes is suggestive. Among those that were owner-occupied, rates did not differ greatly by lender type (Table 6). On rented properties, however, those relying on lending institutions were much more likely to default. The implication may be that, regardless of building type, institutional lenders were more likely to foreclose on rental properties. Private lenders, meanwhile, were more likely to “know the private affairs of the borrower” and so, perhaps, to trust that payment would be forthcoming in due course (Bowie Reference Bowie, Pease and Cherrington1953: 293). Without richer evidence, however, that is only plausible speculation.

Table 6. Tenure, dwelling type, and source of finance on residential buildings, Hamilton, Ontario, 1931

Source: 5 percent longitudinal sample of property assessment records, linked to land registry.

Perhaps the most intriguing result from Hamilton, however, is that default rates on the mortgages held by private individuals (13.7 percent) were lower than those held by institutions (17.0 percent) (Table 6). Contemporary observers, and federal agencies in both Canada and the United States, were skeptical of private investors. Frank Watson, a lawyer and technical staffer who helped draft the legislation that created the U.S. Federal Housing Administration, offered the fullest critique. He criticized them for lacking experience and sense. They preferred old-style, short-term “balloon” mortgages, with interest often payable every six months, instead of the long-term, amortized monthly payments that the FHA promoted (Watson Reference Watson1935: 57–68). Looking back at the Depression experience, Bowie (Reference Bowie, Pease and Cherrington1953: 294) suggested that foreclosures on privately-held mortgages showed that too many investors “had no knowledge, or did not even want to have any, of facts and conditions.” The fact that Hamilton’s private investors were less likely to take possession of residential property than the supposedly more professional lending institutions challenges such arguments.

Significantly, that evidence is consistent with results reported for Baltimore by Rose (Reference Rose2021) and evidence reported in the Financial Survey of 52 U.S. cities in 1934. In Baltimore, in 1930, some affluent borrowers preferred short-term mortgages to the longer-term, amortized versions offered mostly by savings and loans. As for outcomes, the Survey found that in fifteen cities mortgage arrears were higher than average on the first mortgages held by private individuals, but that such arrears were lower than average in thirty-seven cities. Arrears normally point to foreclosures. And indeed, in Cleveland foreclosure rates for private loans were lower than average, and on both owner-occupied and tenanted properties. It may be that some private investors lacked the courage or business sense to foreclose, although most relied on local agents (typically lawyers) who knew the market and how to deal with delinquencies. But, clearly, negative assumptions about the wisdom of private investors were just that: assumptions.

Conclusion

The experience of Hamilton, Ontario, confirms two plausible, but previously untested, expectations about what happened to housing markets in North America during the Depression. First, given how house prices, rents, and vacancies moved in sync in the Canadian and U.S. economies, it is no surprise that rates of mortgage default in Hamilton were close to the U.S. average. Indeed, with minor variations, they followed a similar temporal trajectory, rising in the late 1920s and peaking by the middle of the 1930s. Second, findings for Hamilton are consistent with the fragmentary U.S. evidence that landlords fared worse than homeowners. This was probably because so many were small-time operators, owning one or two properties and therefore vulnerable to a decline in sources of income as well as rents.

And then there are two other findings, less predictable because there has been little basis on which to speculate. The first is that defaults on mortgages provided by private investors were lower than those held by lending institutions. It mattered little that those institutions were more likely to finance apartment buildings, which had the highest vacancy rates. Their relative disadvantage held true even in single-family dwellings. Consistent with the limited available evidence for U.S. cities, this contradicts the assumptions of contemporary experts and agencies. The most significant finding and, given the paucity of evidence, the least predictable is that, when financially strapped, many borrowers relinquished their properties voluntarily. In Hamilton, such defaults accounted for about half the total. This was probably not typical. But it shows that the existence of voluntary defaults should be acknowledged in any interpretation of housing markets and finance during the Depression. Moreover, given that they varied by tenure, building type, and lender, they raise as yet unanswered questions about how different types of owners and investors dealt with one another.

In varying degrees, as suggested at the outset, these findings have relevance beyond North America, and indeed beyond the 1930s. There were certainly variations on the theme, but there is reason to believe that most major findings for Hamilton held true: landlords were more likely to lose their property, private lenders did no worse than institutions, and voluntary defaults – along with informal arrangements – were common. However, none of these claims has been tested. In some ways, comparisons with other economic recessions, for example, that of 2008/9, serve to underline the distinctiveness of the thirties. At that time, home ownership was less common and less leveraged, while financial markets were much more local. But some features of that era have persisted. A small-investor rental market still exists (Mallach Reference Mallach2007); so do private lenders, especially within ethnic and family networks; and, although largely unexplored, it seems likely that voluntary defaults and informal arrangements are still common. Some issues transcend place and time.

So, too, does the approach taken here. The evidence for Hamilton underlines the importance of viewing the housing market as a whole. In the thirties, the complex web of exchange became apparent because governments were drawn into the fray to an unprecedented extent. Tenants, homeowners, and even landlords called on them to help. Provinces (and many states) enacted moratoria and eventually helped, but it was municipalities that bore the brunt. Expenditures rose while tax revenues fell. Like landlords and lenders, they struggled while making concessions. There were very visible conflicts, and plenty of grumbling, but also pervasive compromise. Typically, it had taken a crisis to reveal the character of each individual, whether property owner, investor, or politician, while exposing cracks in the creaking structure on which everyone depended.