Introduction

Sustainable intensification of agriculture can be defined as feeding a growing population while minimizing the impact on the environment, which is high on the global policy agenda and one of the grand challenges facing society (Tilman et al., Reference Tilman, Balzer, Hill and Befort2011; Garnett et al., Reference Garnett, Appleby, Balmford, Bateman, Benton, Bloomer, Burlingame, Dawkins, Dolan, Fraser, Herrero, Hoffmann, Smith, Thornton, Toulmin, Vermeulen and Godfray2013; Petersen and Snapp, Reference Petersen and Snapp2015; NAS, 2021). We must improve our knowledge of management practices that reduce environmental impact while increasing overall production. Harvesting cover crops (CC) has shown promise toward retaining agroecosystem services of CC without harvest, such as erosion control, water quality improvement and weed suppression (Blanco-Canqui et al., Reference Blanco-Canqui, Ruis, Proctor, Creech, Drewnoski and Redfearn2020). Harvesting CC before planting the primary crop may increase overall production by creating a double-cropping system (i.e., two harvestable crops are grown in the same field in succession), which can increase harvestable biomass and provide a revenue stream as livestock forage (Ketterings et al., Reference Ketterings, Swink, Duiker, Czymmek, Beegle and Cox2015; Lyons et al., Reference Lyons, Ketterings, Ort, Godwin, Swink, Czymmek, Cherney, Cherney, Meisinger and Kilcer2019) or bioenergy feedstock (Baker and Griffis, Reference Baker and Griffis2009; Feyereisen et al., Reference Feyereisen, Camargo, Baxter, Baker and Richard2013; Shao et al., Reference Shao, DiMarco, Richard and Lynd2015). Similar systems, such as relay-cropping, have been discussed as resource-efficient technologies that contribute to improved environmental quality, increased net returns and greater overall crop production per unit area than traditional systems (Tanveer et al., Reference Tanveer, Anjum, Hussain, Cerdà and Ashraf2017). Optimizing the management of these systems will be critical to maximizing productivity while maintaining agroecosystem services (Tanveer et al., Reference Tanveer, Anjum, Hussain, Cerdà and Ashraf2017; Blanco-Canqui et al., Reference Blanco-Canqui, Ruis, Proctor, Creech, Drewnoski and Redfearn2020).

Several studies have shown the potential for fertilizer application to increase rye biomass CC production. Balkcom et al. (Reference Balkcom, Duzy, Arriaga, Delaney and Watts2018) reported that in the Southeastern US low rates of commercial N fertilizer resulted in increased rye biomass with similar total costs per Mg of rye compared with unfertilized treatments. Shao et al. (Reference Shao, DiMarco, Richard and Lynd2015) showed that fertilizing and harvesting rye in the Northeastern US can increase biomass and producer revenue compared with unfertilized rye. However, fertilizer applications to CC must be used cautiously since one of the purposes of cover cropping in the drained North Central US is to reduce nutrient loss to the environment. For example, a major benefit of establishing winter rye (Cereal secale L.) CC in corn (Zea mays L.) – soybean systems (Glycine max (L.) Merr.) is to scavenge residual soil nitrogen (N) and reduce nitrate levels in drainage water (Kaspar et al., Reference Kaspar, Jaynes, Parkin and Moorman2007, Reference Kaspar, Jaynes, Parkin, Moorman and Singer2012; NAS, 2021). Soil NO3-N can be reduced by harvesting winter rye compared with non-harvested rye (Krueger et al., Reference Krueger, Ochsner, Porter and Baker2011), and the reduction results in less available N for leaching (Blanco-Canqui et al., Reference Blanco-Canqui, Ruis, Proctor, Creech, Drewnoski and Redfearn2020). A modeling study by Malone et al. (Reference Malone, Obrycki, Karlen, Ma, Kaspar, Jaynes, Parkin, Lence, Feyereisen, Fang, Richard and Gillette2018) showed that double-cropping fertilized rye with soybean reduced N loss to subsurface drainage compared with unharvested and unfertilized rye while also increasing net revenue and harvested biomass.

Rye CC is typically planted using either a grain drill or surface broadcast seeder, and the planting method can affect biomass production. Drilled rye often shows more rapid and more uniform establishment than broadcast seeding because of improved soil-seed contact and protection from erosion events and extreme fluctuations in temperature and water content (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Momen and Kratochvil2011; Bich et al., Reference Bich, Reese, Kennedy, Clay and Clay2014). While drilling must occur after harvest of the primary crop, broadcast seeding can be applied into a standing crop to increase the length of the fall growing season (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Baker and Allan2013). Alternatively, broadcast seeding after primary crop harvest can be accompanied by mechanical incorporation of the seed to improve establishment (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Momen and Kratochvil2011; Brennan and Leap, Reference Brennan and Leap2014). Koehler-Cole et al. (Reference Koehler-Cole, Elmore, Blanco-Canqui, Francis, Shapiro, Proctor, Ruis, Heeren, Irmak and Ferguson2020) reported mixed results when broadcasting rye seeds into standing corn compared with post-harvest drilling. Haramoto (Reference Haramoto2019) compared broadcasting or drilling rye seeds on the same date and reported that drilling led to higher CC biomass under dry soil conditions. Continued research into planting methods is critical to guide farmers' decision-making across a range of operations and equipment availability to maximize success of systems that include winter rye.

A major barrier to widespread adoption of CC is cost. Singer et al. (Reference Singer, Nusser and Alf2007) reported that 56% of farmers in the Northern US soybean region would plant CC if economic incentives were available. More recent studies have also reported that incentives would likely increase CC use (Roesch-McNally et al., Reference Roesch-McNally, Basche, Arbuckle, Tyndall, Miguez, Bowman and Clay2018; Plastina et al., Reference Plastina, Liu, Miguez and Carlson2020). Blanco-Canqui et al. (Reference Blanco-Canqui, Ruis, Proctor, Creech, Drewnoski and Redfearn2020) reported that double-crop CC planting may improve net returns, but more research on management scenarios is needed. While double-cropping soybean systems have been reported to increase production and producer revenue since the 1980s in the Southeastern US (Marra and Carlson, Reference Marra and Carlson1986), only recently have such systems been discussed as profitable as far north as Minnesota, US, and Ontario, Canada (Gesch and Archer, Reference Gesch and Archer2013; Gesch et al., Reference Gesch, Archer and Berti2014; Davidson, Reference Davidson2016). The two US states with the largest soybean production, Iowa and Illinois (National Agricultural Statistics Service, 2020; Shahbandeh, Reference Shahbandeh2021), are located in the Northern US soybean region, and each had less than 3% of corn and soybean land in CC in 2015 (Rundquist and Carlson, Reference Rundquist and Carlson2017). Therefore, identifying methods to profitably implement a double-crop CC system within this region could help make the practice more attractive to a large segment of producers.

Finding a combination of management practices that contribute to sustainable intensification must balance productivity, profitability and environmental quality. From a bioenergy perspective, the energy balance of double-cropping systems is an important consideration. For example, Gesch et al. (Reference Gesch, Archer and Berti2014) reported less net energy from double-cropping camelina-soybean systems than soybean-only systems. Similarly, management influences on greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions can be used to evaluate potential tradeoffs between productivity and sustainability goals (Camargo et al., Reference Camargo, Ryan and Richard2013; Malone et al., Reference Malone, Herbstritt, Ma, Richard, Cibin, Gassman, Zhang, Karlen, Hatfield, Obrycki, Helmers, Jaynes, Kaspar, Parkin and Fang2019). Although double-cropping soybean systems show promise in the North Central US, few field studies have addressed agronomic management of these systems. Here, we evaluate how rye planting methods and N fertilizer rates affect rye biomass yields and N content in a winter rye-soybean double-cropping system; and consider potential costs, estimated energy balances and estimated GHG emissions.

Material and methods

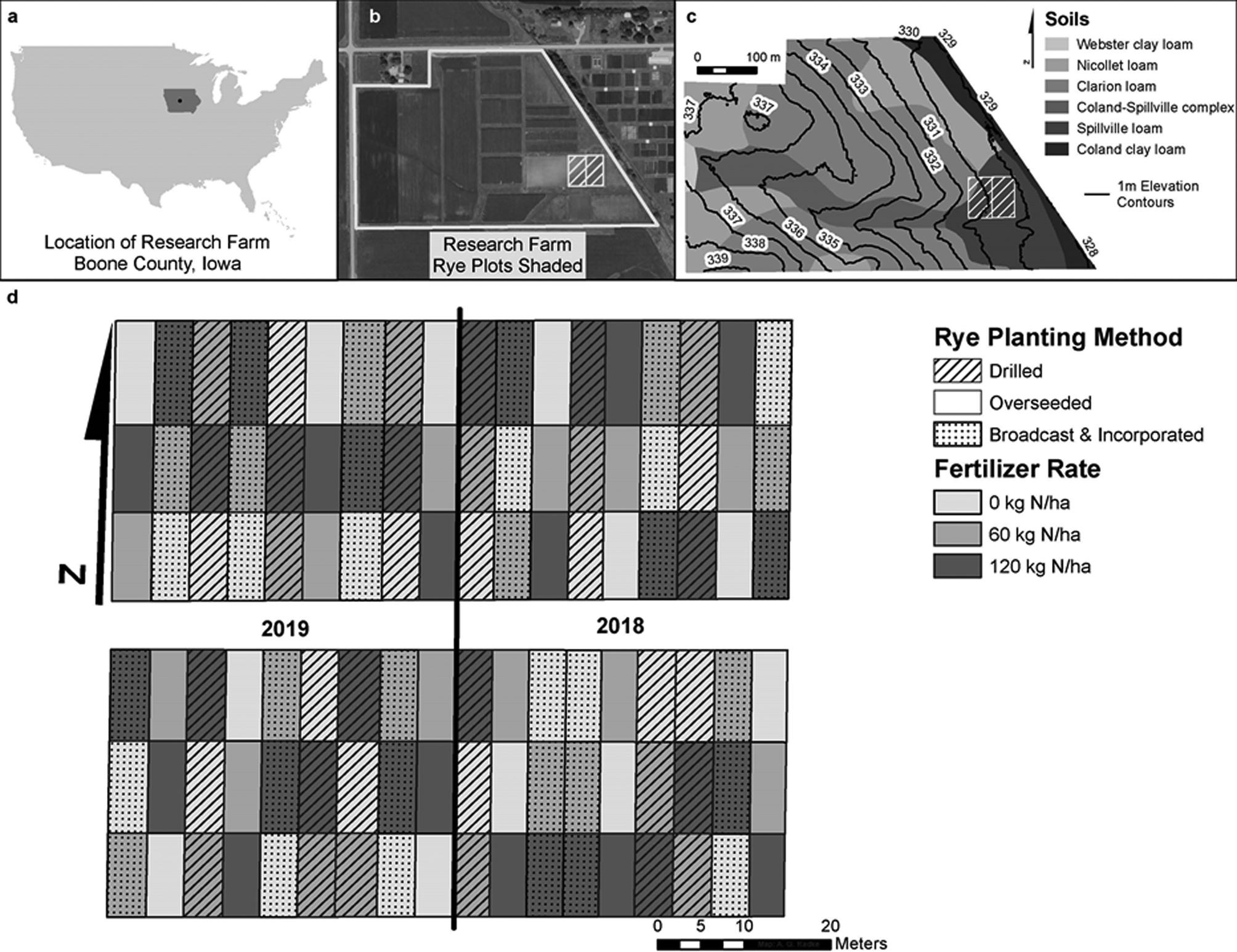

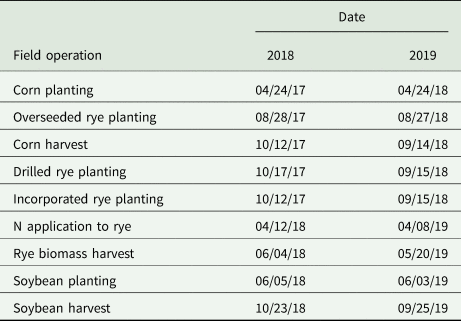

We initiated a field study in 2017 on a site approximately 10 km west of Ames, IA in Boone County (42°00′N; 93°47′W), with Spillville loam (Fine-loamy, mixed, superactive, mesic Cumulic Hapludoll) as the predominant soil type. Field plots were laid out in a split-plot randomized complete block design with six replications (blocks). Each year main plots (3.8 × 30.5 m, n = 18) were assigned to three planting methods, and subplots (3.8 × 9.1 m, n = 54) to three N rates (Fig. 1). Two sets of plots (east and west) were managed under a 2-year rotation with one year in corn and the other year in rye-soybean. The rye was planted during corn growth or shortly after harvest (Table 1). In 2018, the west field was in corn and the east field was in rye-soybean. In 2019, the crops were reversed (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Study area and plot design with (a) research farm location in Central Iowa, approximately 10 km west of Ames; (b) orthophoto showing research farm boundaries and site of rye plots, eastern plots studied in 2018 and western plots studied in 2019; (c) soils and topography of research farm with rye sites; and (d) study plot layout, showing whole- and sub-plots and north blocks separated from south blocks by a grass driveway. Note plots are not aligned perfectly on a north-south axis due to field conditions.

Table 1. Field operation dates (mm/dd/yy) for the two growing seasons when rye biomass was harvested in 2018 and 2019

Crop management and analysis

The corn and soybean were managed as a typical Central Iowa no-till system (Table 1). Weeds were controlled through a combination of preemergence and postemergence herbicides for both corn and soybean. Soybean (Pioneer P20T79R, 445,000 seeds ha−1) and corn (Viking A81-98R, 86,000 seeds ha−1) were planted with a five-row, 0.76 m row width, no-till planter. N fertilizer (32% urea ammonium nitrate, 32-0-0) was applied to corn in each growing season at planting (34 kg ha−1) and side-dressed (170 kg ha−1) along the row at V4.

Winter rye ‘Elbon’ was planted during the corn phase of the rotation using three methods: (1) drilled after corn harvest (row width = 19.0 cm; depth = 2.5 cm), (2) overseeded, i.e., broadcast over corn with a spinner spreader mounted on a high-boy tractor at the R6 growth stage, and (3) incorporated, i.e., broadcast and shallow incorporated with a rolling stalk chopper after corn harvest. Rye seeding rates for the three planting methods were 247, 371 and 309 pure live seed (PLS) m−2; or 55, 82 and 69 kg total seeds ha−1 using 51,809 total seeds kg−1 and 85% germination. Similarly, seed supplier Green Cover Seed lists a seed weight of 50,700 ‘Elbon’ seeds kg−1 (Green Cover Seed, 2021). Higher rye seeding rates are recommended in Iowa for broadcast compared with drilled seeding. In early April, we fertilized subplots within each planting method with three rates of surface applied granular urea (46-0-0): (1) 0 kg N ha−1, (2) 60 kg N ha−1 and (3) 120 kg N ha−1 (Fig. 1). Early spring can be the optimum time to apply N to winter crops in the North Central US (Franzen, Reference Franzen2018; Malone et al., Reference Malone, Obrycki, Karlen, Ma, Kaspar, Jaynes, Parkin, Lence, Feyereisen, Fang, Richard and Gillette2018).

At the flowering stage, we hand-clipped plants to the soil surface within a 0.38 m2 rectangular frame. Biomass samples were dried at 60°C until weights were stable, and weights were scaled up based on frame size to Mg ha−1 dry matter (DM). The collected rye biomass was finely ground and analyzed for C and N content using the dry combustion method (FlashSmart C and N analyzer; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). The remaining rye not collected for analysis was green-chopped and collected as ensilage. Soybean seed yields were determined by harvesting each main plot area, weighing the grain and measuring grain moisture. Although a control treatment without winter rye was not implemented, we compared soybean yields with Boone County, Iowa averages from National Agricultural Statistics Service (2021). We calculated N recovery efficiency (REN) by the difference method, where REN is the difference of N in rye biomass between fertilized and unfertilized treatments divided by the amount of fertilizer N added (Cassman et al., Reference Cassman, Dobermann and Walters2002).

Economic analysis

We estimated biomass production costs associated with the different treatments, including establishment, fertilization and harvest costs. We estimated unfertilized rye establishment costs at $92–$110 ha−1 for the different treatments, assuming seed costs of $0.67 kg−1 and $55 ha−1 for custom no-till planting (Plastina and Johanns, Reference Plastina and Johanns2021). Costs related to rye planting and labor in our analysis differed only according to the seeding rate, although costs for the different methods for on-farm implementation may differ based on field conditions, producer operations and equipment availability. Also, the planting costs used are higher than those recently reported for drilling or broadcasting CC seeds (Plastina and Johanns, Reference Plastina and Johanns2021), but are similar to the $99 ha−1 reported by Balkcom et al. (Reference Balkcom, Duzy, Arriaga, Delaney and Watts2018) and less than the $151 ha−1 reported by Roley et al. (Reference Roley, Tank, Tyndall and Witter2016). While Balkcom et al. (Reference Balkcom, Duzy, Arriaga, Delaney and Watts2018) and Roley et al. (Reference Roley, Tank, Tyndall and Witter2016) included rye termination costs, we did not include these costs because harvesting the rye at the flowering stage effectively terminated growth, thereby negating the need for additional management (Clark, Reference Clark2007). However, CC termination cost using herbicide will increase the production costs, which Roley et al. (Reference Roley, Tank, Tyndall and Witter2016) estimated at $45 ha−1.

We assume winter rye was harvested as hay, which takes about 3 days under good conditions to cure in the field after mowing (Porter, Reference Porter2017). In Iowa, the first alfalfa hay cutting can be mid-May (Barnhart, Reference Barnhart2010), which is comparable to or earlier than our harvest dates (Table 1). Assuming mowing, raking and tedding at $63.4 ha−1 and baling and moving large round bales to storage at $22.4 Mg−1 DM harvested, total on-farm custom harvest costs not including nutrient replacement were $175.4 ha−1 for 5.0 Mg rye harvested (Plastina and Johanns, Reference Plastina and Johanns2021). In comparison, if rye harvest costs were similar to harvesting corn stover for biofuel as Baker and Griffis (Reference Baker and Griffis2009) assumed, estimated rye harvest costs when the producer owns all the necessary equipment (or custom rates) would be $101 ha−1 (or $179 ha−1) using the values reported by Edwards (Reference Edwards2014) for corn stover harvest in Iowa without including hauling or nutrient replacement costs. Graham et al. (Reference Graham, Nelson, Sheehan, Perlack and Wright2007) reported $106 ha−1 for 3.5 Mg of shredded/raked/baled corn stover without hauling but including nutrient replacement.

We estimated dry fertilizer N application costs at $15 ha−1 (Plastina and Johanns, Reference Plastina and Johanns2021), which is similar to Balkcom et al. (Reference Balkcom, Duzy, Arriaga, Delaney and Watts2018). Fertilizer prices were estimated at $0.88 kg-N−1 (Mensing, Reference Mensing2019), $0.66 kg-K2O−1 and $0.86 kg-P2O5−1. We estimated P and K inputs based on 3.5 and 13.0 kg P2O5 and K2O removed per Mg rye CC harvested (from FEAT Model described below). We did not include field application costs of P and K, assuming them to be unchanged with or without rye.

Overall, the total production costs for 5.0 Mg of unfertilized harvested rye biomass ranged from $267 to $285 ha−1. Adding P, K and N fertilizer increased these costs to between $325 and $464 ha−1 depending on seeding and fertilizer rates. We calculated the cost of producing one Mg of biomass DM as the total production cost divided by harvestable biomass. While rye was clipped to the soil surface during collection, we estimated harvestable biomass by subtracting 0.75 Mg from total aboveground biomass. A 10 cm rye height can be assumed equal to 1 Mg rye aboveground biomass, and 7.5 cm height is acceptable to maintain soil ecosystem services when harvesting CC with high soil surface residue after no-till corn (Blanco-Canqui et al., Reference Blanco-Canqui, Ruis, Proctor, Creech, Drewnoski and Redfearn2020).

The costs above do not include a potential reduction in soybean yield resulting from the double-cropping system, which can occur when harvesting an overwintering crop in late May or early June (Gesch et al., Reference Gesch, Archer and Berti2014; Nafzinger et al., Reference Nafziger, Villamil, Niekamp, Iutzi and Davis2016). Breakeven prices for harvested rye were calculated as the price needed to generate net revenue equal to that without soybean yield reduction (Gesch et al., Reference Gesch, Archer and Berti2014):

where Pr is the breakeven rye price ($ ha−1), Ps is the soybean price (assumed $400 Mg−1 DM), Ys0 is the countywide soybean yield (Mg DM ha−1) for the year (National Agricultural Statistics Service, 2021), Ysr is the soybean yield (Mg DM ha−1) with harvested rye treatments, Yri is the rye yield (Mg DM ha−1) for treatment i, and Cri is the rye production costs ($ ha−1) for treatment i. For rye prices below this breakeven level, growing soybean alone would be more profitable than the double-crop system. This approach provides an indication of the minimum rye price that would be needed for a double-crop system to be more profitable than prevailing practices without considering off-site transportation costs.

Energy budgets and GHG with FEAT

We estimated energy balances and GHG emissions for each rye treatment based on inputs and outputs in the field operations using the Farm Energy Analysis Tool (FEAT) version 1.2.7 (Camargo et al., Reference Camargo, Ryan and Richard2013), unless otherwise noted. Operations associated with corn and soybean management were assumed to remain the same with or without rye. Therefore, included in the energy and GHG balance were only on-farm fuel use for seeding, fertilizing and harvesting the rye, and energy and emissions resulting from the production of seeds, N, P and K fertilizer based on N rate and replacement of P and K exported in crop biomass and transport of inputs. The energy associated with on-farm fuel use (44.8 MJ L−1) and transportation associated with inputs (0.64 GJ Mg−1) were estimated based on the FEAT database. We did not include energy inputs and emissions resulting from transportation after harvest.

Energy inputs and outputs were as follows (GJ Mg−1): N 54.8; P 10.3; K 7.0; rye seeds 6.2; rye biomass 21.8; soybeans 23.8. Energy input associated with on-farm fuel use was estimated using 20 L ha−1 diesel for planting and harvesting rye, and 1.7 L ha−1 for N fertilizer application. Fuel use for P and K were not included, and this fuel use was assumed to be the same with or without rye in corn-soybean systems. Net energy of each treatment was calculated by subtracting the energy input from the output of the harvested rye and subtracting the reduced energy output with the estimated soybean yield reduction (Ys0 − Ysr from Equation 1).

IPCC emission factors for wet climates were used to estimate direct emissions of N2O from soils following N fertilization (1.6%) and N content in above and below-ground residues (0.6%) resulting from rye management (Hergoualc'h et al., Reference Hergoualc'h, Akiyama, Bernoux, Chirinda, del Prado, Kasimir, MacDonald, Ogle, Regina, van der Weerden, Calvo Buendia, Tanabe, Kranjc, Baasansuren, Fukuda, Osako, Pyrozhenko, Shermanau and Federici2019). Calculations in FEAT were followed except where field data for biomass N content and residue remaining after harvest could be input. Estimates of N2O emissions were converted to kg CO2-e (CO2-equivalent) ha−1 using the 100-year estimated warming potential with climate-carbon feedbacks of 298 kg CO2-e kg N2O−1 (Myhre et al., Reference Myhre, Shindell, Bréon, Collins, Fuglestvedt, Huang, Koch, Lamarque, Lee, Mendoza, Nakajima, Robock, Stephens, Takemura, Zhang, Stocker, Qin, Plattner, Tignor, Allen, Boschung, Nauels, Xia, Bex and Midgley2013).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using PROC MIXED in SAS (version 9.4, SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA) for split-plot designs to determine the impact of N fertilizer and planting method on rye biomass, N content, REN, and energy and economic parameters. The fixed effects were N rate, planting method and their interactions; the random effects were replication (the blocking factor) and the whole-plot error (the interaction between replication and the whole-plot factor – the planting method). Pairwise comparisons were made using the Tukey–Kramer test when main effects were significant at P < 0.05. We separated data by growing season because of differences in weather conditions and field plot locations. Data were also analyzed using PROC MIXED with year included as a random effect to determine whether treatments were significantly different regardless of year.

Results and discussion

Growing conditions

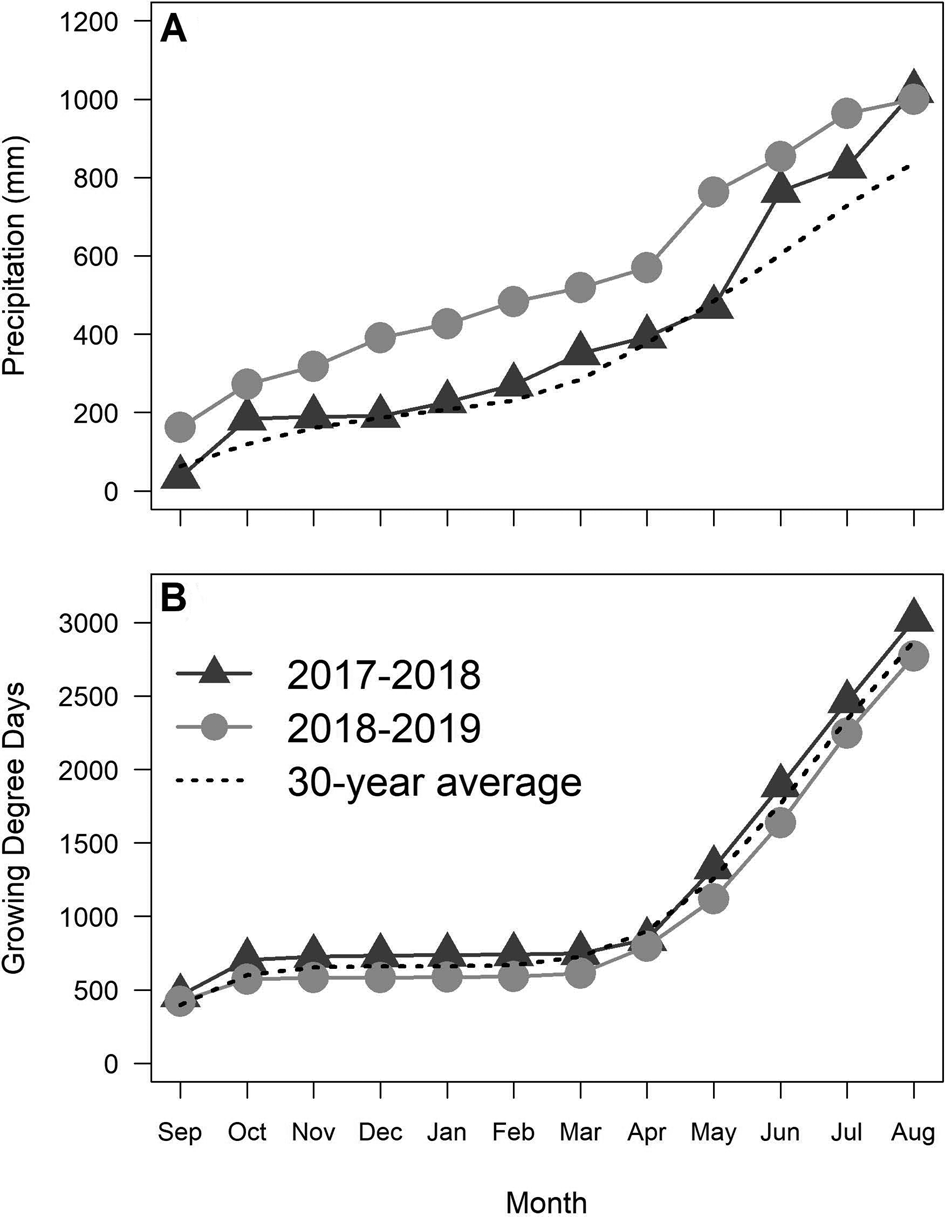

Annual cumulative September through August rainfall during each of the two growing seasons was approximately 1000 mm, above the average of 860 mm (Fig. 2a). The 2017–2018 rainfall was similar to the 30-year average until June 2018, when the monthly rainfall was 296 mm compared with the average of 121 mm. In September 2018, the rainfall was 91 mm greater than the average, and the cumulative rainfall remained above average through August 2019. While rainfall in both years was above average, June through August 2019 received 314 mm less rainfall than 2018 and 110 mm less than the average. Cumulative rye growing degree days (GDD; base 4.4°C) for September through May were 1332°C days in 2017–2018 and 1119°C days in 2018–2019, while the average was 1247°C days (Fig. 2b). The warmer October 2017 and May 2018 compared with 2018–2019 were the largest monthly GDD differences between the two growing seasons.

Fig. 2. Monthly precipitation (a) and growing degree day (4.4°C) (b) for the two growing seasons, 2018 and 2019, plotted with the 30-year averages (1990 through 2019).

Soybean yields

Overall soybean yields in 2018 (3.8 Mg ha−1) were similar to the county average of 3.7 Mg ha−1, but the yields in 2019 were 0.6 Mg ha−1 lower than the county average of 3.6 Mg ha−1 (National Agricultural Statistics Service, 2021). Although precipitation and GDD were close to the 30-year averages (Fig. 2), the reduction in overall yield in 2019 may be partly a result of lower 2019 June through August precipitation. Also, in-field variability between the east and west plot areas may be related to the roughly 1 m higher field elevation in 2019 compared with 2018 (Fig. 1). Kravchenko and Bullock (Reference Kravchenko and Bullock2000) reported that elevation influenced soybean yield, with higher yields consistently observed at lower landscape positions.

Soybean yields were not determined in subplots of N fertilizer rates because of logistical constraints, but adding fertilizer N to rye prior to soybean was only expected to have a small effect, if any, on soybean yields (Salvagiotti et al., Reference Salvagiotti, Cassman, Specht, Walters, Weiss and Dobermann2008; Mourtzinis et al., Reference Mourtzinis, Kaur, Orlowski, Shapiro, Lee, Wortmann, Holshouser, Nafziger, Kandel, Niekamp, Ross, Lofton, Vonk, Roozeboom, Thelen, Lindsey, Staton, Naeve, Casteel, Wiebold and Conley2018). While high N fertilizer rates (>200 kg N ha−1) to soybean can increase soybean yields in Iowa and Nebraska (Bakhsh et al., Reference Bakhsh, Kanwar, Baker, Sawyer and Malarino2009; Cafaro et al., Reference Cafaro La Menza, Monzon, Lindquist, Arkebauer, Knops, Unkovich, Specht and Grassini2020), only small N-related effects on soybean yields have generally been detected (Mourtzinis et al., Reference Mourtzinis, Kaur, Orlowski, Shapiro, Lee, Wortmann, Holshouser, Nafziger, Kandel, Niekamp, Ross, Lofton, Vonk, Roozeboom, Thelen, Lindsey, Staton, Naeve, Casteel, Wiebold and Conley2018). Soybean yields are typically not reduced following unharvested rye CC (Acharya et al., Reference Acharya, Moorman, Kaspar, Lenssen and Robertson2020; Koehler-Cole et al., Reference Koehler-Cole, Elmore, Blanco-Canqui, Francis, Shapiro, Proctor, Ruis, Heeren, Irmak and Ferguson2020), though corn yields are sometimes decreased (Kaspar and Bakker, Reference Kaspar and Bakker2015; Pantoja et al., Reference Pantoja, Woli, Sawyer and Barker2015). However, further investigation into soybean yields in double-cropping systems is warranted, as the later rye termination from harvest and later soybean planting date may reduce yields by shortening the growing season (Egli and Cornelius, Reference Egli and Cornelius2009; Hu and Wiatrak, Reference Hu and Wiatrak2012). Also, double- or relay-cropping soybean systems can use more water than single-cropping systems in the North Central US (Gesch and Johnson, Reference Gesch and Johnson2015), and a main limiting factor in double-cropping soybean systems is limited soil water availability (Santos Hansel et al., Reference Santos Hansel, Schwalbert, Shoup, Holshouser, Parvej, Vara Prasad and Ciampitti2019). Despite some studies in the Northern US soybean region reporting lower soybean yields when double-cropping, these systems have the potential for higher total crop yields (Gesch et al., Reference Gesch, Archer and Berti2014; Nafzinger et al., Reference Nafziger, Villamil, Niekamp, Iutzi and Davis2016; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Wells, Anderson, Gesch, Forcella and Wyse2017).

Rye biomass

Growing conditions for both 2018 and 2019 were favorable for rye biomass production, with precipitation higher than the 30-year average and GDD approximately average for both years (Fig. 2). Averaged across planting methods and N rates, Table 2 shows above ground biomass was slightly higher in 2018 (6.1 ± 1.3 Mg ha−1) than in 2019 (5.5 ± 1.6 Mg ha−1). This may be attributed to (1) more GDD total in September 2017 through May 2018 (Fig. 2), (2) the later rye harvest date in 2018 (Table 1), and (3) rye being N limited in 2019 but not in 2018 as discussed below. For the 60 kg ha−1 N rate, the rye biomass was similar between years and the difference was less compared with the unfertilized treatment (6.3 vs 5.9 and 5.9 vs 4.1 Mg ha−1, Table 2). Overall, rye biomass production in this study was similar to ranges reported in Alabama (Balkcom et al., Reference Balkcom, Duzy, Arriaga, Delaney and Watts2018) and Maryland (Mirsky et al., Reference Mirsky, Spargo, Curran, Reberg-Horton, Ryan, Schomberg and Ackroyd2017), and exceeded production in Nebraska (Koehler-Cole and Elmore, Reference Koehler-Cole and Elmore2020; Koehler-Cole et al., Reference Koehler-Cole, Elmore, Blanco-Canqui, Francis, Shapiro, Proctor, Ruis, Heeren, Irmak and Ferguson2020) and Kentucky (Haramoto, Reference Haramoto2019).

Table 2. Mean values (with standard deviations) for rye aboveground biomass dry matter, accumulated aboveground N content in the biomass and N fertilizer recovery efficiency (REN) for the two growing seasons, 2018 and 2019

*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant.

Different letters indicate significant differences within column identified by the Tukey–Kramer test at α = 0.05 level.

Data are reported by rye planting method (drilled after corn harvest, broadcast and overseeded into R6 corn, and broadcast and incorporated after corn harvest) and by fertilizer N application rate (0, 60 and 120 kg N ha−1). Data for REN are not pooled by planting method. Estimated harvestable biomass and N removed are biomass – 0.75 and aboveground N × (biomass-0.75) × biomass−1.

Above-average precipitation and consistent GDDs in both rye growing seasons likely reduced differences between planting methods. Fall establishment of CC by drilling is typically more uniform and rapid than broadcast (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Momen and Kratochvil2011; Noland et al., Reference Noland, Wells, Sheaffer, Baker, Martinson and Coulter2018), but these advantages are most evident in dry conditions (Haramoto, Reference Haramoto2019; Koehler-Cole et al., Reference Koehler-Cole, Elmore, Blanco-Canqui, Francis, Shapiro, Proctor, Ruis, Heeren, Irmak and Ferguson2020). Thus, overseeded and drilled rye produced similar biomass in 2018, but incorporated rye produced significantly higher biomass (Table 2). Seed incorporation likely improved production compared with the overseeded treatment because improved seed-soil contact typically improves germination and emergence, leading to greater biomass production (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Momen and Kratochvil2011; Brennan and Leap, Reference Brennan and Leap2014; Peterson et al., Reference Peterson, Berti and Samarappuli2019). Any advantage of earlier planting and higher seed rate in the overseeded treatment was likely offset by only 36 mm of precipitation in September of 2017 compared with an average of 71 mm (Fig. 2). The higher-than-normal precipitation that facilitated establishment did not occur until October, when the other treatments had also been seeded. Additionally, the broadcast and incorporated rye likely outproduced the drilled treatment because of increased seeding rates, which can lead to more biomass (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Allan, Baker and Pagliari2019; Koehler-Cole and Elmore, Reference Koehler-Cole and Elmore2020), though that is not always a consistent response (Haramoto, Reference Haramoto2019). Conversely, September precipitation in the 2019 season led to the early establishment of the overseeded treatment (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Baker and Allan2013); the early establishment allowed a longer growing season that, coupled with the highest seeding rate, contributed to the overseeded treatment producing the most biomass (although not significantly higher than the other two planting methods, Table 2).

Averaged over both years, biomass DM values for the unfertilized and 60 kg N ha−1 plots were 5.0 and 6.1 Mg ha−1 and were significantly different (Table 2). However, in 2018, rye biomass production was not increased by N fertilizer, suggesting that N was not a limiting factor for biomass production (Table 2). Despite rye typically displaying a biomass response to N fertilizer in the Southeast to the Northeast US (Reiter et al., Reference Reiter, Reeves, Burmester and Torbert2008; Mirsky et al., Reference Mirsky, Spargo, Curran, Reberg-Horton, Ryan, Schomberg and Ackroyd2017; Balkcom et al., Reference Balkcom, Duzy, Arriaga, Delaney and Watts2018), N demands in 2018 in our North Central US site were likely met by a combination of residual N from the preceding corn crop and soil N mineralization. The east plot area producing rye in 2018 was at the bottom of a slope (Fig. 1). Mamo et al. (Reference Mamo, Malzer, Mulla, Huggins and Strock2003) reported that field areas non-responsive to N were mostly at lower elevations, likely having increased N availability and mineralization.

Conversely, rye biomass did respond to N fertilization in 2019, suggesting that residual N and soil N mineralization did not meet crop N demand in the higher elevation west plot area (Fig. 1). While adding N fertilizer increased biomass production compared with the unfertilized treatments, the highest rate, 120 kg N ha−1, did not produce significantly more than the 60 kg N ha−1 treatment (Table 2). This finding roughly agrees with Mirsky et al. (Reference Mirsky, Spargo, Curran, Reberg-Horton, Ryan, Schomberg and Ackroyd2017), who found that 72.4 kg N ha−1 was needed to reach maximum rye biomass production. Similarly, a study in Canada indicated that N fertilization above 42 kg N ha−1 for rye was not justified (Landry et al., Reference Landry, Janovicek, Lee and Deen2019).

Blanco-Canqui et al. (Reference Blanco-Canqui, Ruis, Proctor, Creech, Drewnoski and Redfearn2020) reported that while more research is needed, the few studies available indicate that CC harvesting does not generally affect ecosystem services such as soil properties, erosion and weed suppression. In our study, even without fertilization, the rye produced enough biomass to provide agroecosystem services based on yields reported in other studies. Rye reduced nitrate concentrations in subsurface drainage with much lower biomass (<2 Mg ha−1) in Iowa corn-soybean systems (Kaspar et al., Reference Kaspar, Jaynes, Parkin, Moorman and Singer2012). Rye biomass production of 3.5–4.0 Mg ha−1 effectively reduced runoff and soil erosion in Wisconsin monocrop corn silage production by more than 50% (Siller et al., Reference Siller, Albrecht and Jokela2016), while less than 1 Mg ha−1 of rye biomass reduced erosion rates in 2 out of 3 years in a no-till corn-soybean system (Kaspar et al., Reference Kaspar, Radke and Laflen2001). Similarly, CC biomass of about 4 Mg ha−1 suppressed weeds prior to main crop planting in a Pennsylvania corn-oat production system (Finney et al., Reference Finney, White and Kaye2016), although others report that 8 Mg ha−1 biomass or more is needed to reduce weed pressure on subsequent main crops (Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, Curran, Grantham, Hunsberger, Mirsky, Mortensen, Nord and Wilson2011; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Reberg-Horton, Place, Meijer, Arellano and Mueller2011).

Rye N content and potential leaching

The amount of N in rye aboveground biomass differed among planting methods in 2018, but not in 2019 (Table 2). The incorporated method had the highest amount of biomass N in 2018, reflecting higher total biomass production. In both years, N application led to greater biomass N content (Table 2) compared with unfertilized plots. Two-year average N content values for the unfertilized and 60 kg N ha−1 rates were 57.7 and 88.4 kg N ha−1 and were significantly different. Notably, in 2018 the higher N content in the fertilized treatments occurred despite similar biomass production (Table 2) and developmental rates (data not shown) among the three N rates, indicating that biomass N concentration was higher in the fertilized treatments. The higher rye biomass N concentration occurred despite little increase in overall biomass production, which is consistent with Lyons et al. (Reference Lyons, Ketterings, Ort, Godwin, Swink, Czymmek, Cherney, Cherney, Meisinger and Kilcer2019) that reported rye biomass N content can increase beyond the N rate that optimized yield.

The N content in aboveground biomass and estimated N removed during rye harvest exceeded the additional N applied in the 60 kg ha−1 treatment in both years but not in the 120 kg ha−1 treatment (Table 2). REN peaked at 63.8% in 2019 and reached only 38.5% in 2018 in the 60 kg N ha−1 treatment. In comparison, Balkcom et al. (Reference Balkcom, Duzy, Arriaga, Delaney and Watts2018) reported approximately 50% REN for rye across three fertilizer rates of spring applications (34, 67 and 101 kg N ha−1). These findings suggest some reduction in a CC's ability to limit N loss in the fertilized system, but the fertilized rye double-cropping system may still lead to a reduction in soil N and N losses compared with a no-CC scenario. This finding is critical in Iowa because water quality deterioration caused by excessive nitrate levels is an ongoing concern (Dinnes et al., Reference Dinnes, Karlen, Jaynes, Kaspar, Hatfield, Colvin and Cambardella2002; Hatfield et al., Reference Hatfield, McMullen and Jones2009; Syswerda et al., Reference Syswerda, Basso, Hamilton, Tausig and Robertson2012), so any management practice that reduces the potential for nitrate leaching should be considered. In a modeling study, Malone et al. (Reference Malone, Obrycki, Karlen, Ma, Kaspar, Jaynes, Parkin, Lence, Feyereisen, Fang, Richard and Gillette2018) reported that fertilized and harvested rye in corn-soybean rotations reduced drainage N loss by 18% compared with rye CC that was neither fertilized nor harvested. In a nearby field with similar soil and other conditions, Kaspar et al. (Reference Kaspar, Jaynes, Parkin, Moorman and Singer2012) reported unfertilized and unharvested rye reduced N concentration in drainage water 48–58%. So, even without removing rye and the associated organic N, considerable N reduction in drainage water under similar conditions has been reported when including CC. These findings suggest that harvesting rye at an N application of 60 kg N ha−1 may reduce nitrate leaching and N loss to subsurface drainage and surface water compared with no CC or unharvested and unfertilized CC.

Nonetheless, spring N application must be carefully managed because most tile drainage occurs during spring months (Jaynes et al., Reference Jaynes, Kaspar, Moorman and Parkin2008; Waring et al., Reference Waring, Lagzdins, Pederson and Helmers2020) and some fertilizer N loss would be carried out of tile drainage lines and discharged to surface waters. For example, the lower elevation plots in the current study with rye in 2018 did not require N fertilizer for additional biomass production, and management decisions such as higher or lower fertilizer rates can depend on field variability. Precision N management of crops within a field has been reported to contribute to sustainable food production without degrading the environment (Diacono et al., Reference Diacono, Rubino and Montemurro2013; NAS, 2021).

Economics

In 2018, planting method and fertilizer rate affected cost required to produce an Mg of harvested biomass (Table 3). The biggest cost difference in 2018 was between N rates of 0 and 120 kg N ha−1 ($26.8 Mg−1), where the fertilizer costs were not offset by higher biomass. The overseeded method had the highest cost resulting from the highest seeding rate and low biomass. In 2019, neither fertilizer rate nor planting method significantly affected costs because the higher seed and fertilizer costs were offset by higher biomass. Averaged over both years, costs for the 0 and 60 kg N ha−1 rates were $77.4 and $79.7 Mg−1 (and were not significantly different). The costs per Mg of rye biomass are nearly twice the $44 Mg−1 reported by Balkcom et al. (Reference Balkcom, Duzy, Arriaga, Delaney and Watts2018) in a study with approximately half the rye biomass (~2.2 Mg ha−1), partly because of including P and K replacement and other harvesting costs in the current study.

Table 3. Mean values (with standard deviations) for energy balance components, production costs and breakeven prices for the two growing seasons, 2018 and 2019

*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant.

Different letters indicate significant differences within column identified by the Tukey–Kramer test at α = 0.05 level.

Data are reported by rye planting method (drilled after corn harvest, broadcast and overseeded into R6 corn, and broadcast and incorporated after corn harvest) and by fertilizer N application rate (0, 60 and 120 kg N ha−1). Net energy and breakeven price estimates include soybean yield reduction in 2019. Note that breakeven prices in 2018 are equal to production costs because soybean yield was similar to the county average. Energy output, net energy, costs and prices were based on estimated harvestable biomass (see Table 2).

With no apparent effect on soybean yield in 2018, the breakeven price would be the rye production costs ($67.4 and $77.5 Mg−1 for 0 and 60 kg N ha−1). Although this study did not include a no-rye treatment, we estimated the effects of potential reduction in soybean yields on breakeven prices by comparing with the county average in 2019. The 0.6 Mg ha−1 soybean yield reduction in 2019 contributed to breakeven prices of $166 and $131 Mg−1 for N rates of 0 and 60 kg N ha−1 (Table 3). Thus, the breakeven price was lower for fertilized compared with unfertilized rye in 2019. Averaged over both years, breakeven prices for the unfertilized and 60 kg N ha−1 rates were $117 and $104 Mg−1 (and were not significantly different). Assuming fertilized and unfertilized rye have nearly the same potential price per Mg as reported by Shao et al. (Reference Shao, DiMarco, Richard and Lynd2015), the slightly lower breakeven price and significantly higher yield for the fertilized rye across the current 2-year study indicate that fertilizer input would be neutral to economically viable in these conditions and help sustainably intensify agriculture.

The zero N rate rye production cost of $77.4 Mg−1 averaged over the 2-year study is similar to the estimated $75 Mg−1 for harvested and unfertilized rye biomass reported by Baker and Griffis (Reference Baker and Griffis2009) and used by Malone et al. (Reference Malone, Obrycki, Karlen, Ma, Kaspar, Jaynes, Parkin, Lence, Feyereisen, Fang, Richard and Gillette2018). If the fertilizer cost increases from $0.88 to $1.33 kg-N−1 (Malone et al., Reference Malone, Obrycki, Karlen, Ma, Kaspar, Jaynes, Parkin, Lence, Feyereisen, Fang, Richard and Gillette2018), the breakeven price for the 60 kg N ha−1 fertilized rye-soybean double-crop system increases from $104 to $110 Mg−1 over the 2-year study, which is still slightly lower than unfertilized rye. While N application in rye production after corn on high organic matter soils is recommended in the Northern US soybean region (Kaiser, Reference Kaiser2018), Malone et al. (Reference Malone, Herbstritt, Ma, Richard, Cibin, Gassman, Zhang, Karlen, Hatfield, Obrycki, Helmers, Jaynes, Kaspar, Parkin and Fang2019) reported only small reductions in soil organic C and N in Central Iowa long-term corn-soybean rotations with removal of C and N through corn stover harvest without N replacement. Thus, N application may not be required to prevent reduced soil organic matter. Further, economically optimum N fertilizer rates within a field can vary substantially over short distances and year-to-year (Mamo et al., Reference Mamo, Malzer, Mulla, Huggins and Strock2003; Scharf et al., Reference Scharf, Kitchen, Sudduth, Davis, Hubbard and Lory2005), suggesting the lower elevation plots of the current study with rye harvested in 2018 require less N fertilizer on average over several years than the slightly higher elevation plots of rye harvested in 2019.

For comparison with our breakeven prices: (1) prices for good grass hay in Iowa were >$120 Mg−1 in 2021 (AMS, 2021; Hay and Forage Grower, 2021) and (2) value for rye as a bioenergy feedstock plus coproducts were >$150 Mg−1 (Shao et al., Reference Shao, DiMarco, Richard and Lynd2015) or ~$400 Mg−1 (Herbstritt et al., Reference Herbstritt, Richard, O'Brien, Emmett, Karlan, Kasper, Kohler, Wu, Lence and Malone2022). Note, however, that bioenergy feedstock or silage involves different operations (and therefore costs) than hay. If the rye market price were below the breakeven prices calculated here or breakeven prices were higher (e.g., including off-site transportation or higher harvest/operation costs), positive value may still be present factoring in the ecosystem services associated with the harvested rye (Balkcom et al., Reference Balkcom, Duzy, Arriaga, Delaney and Watts2018; Blanco-Canqui et al., Reference Blanco-Canqui, Ruis, Proctor, Creech, Drewnoski and Redfearn2020).

Winter rye has potential as a cellulosic bioenergy feedstock in the US (Baker and Griffis, Reference Baker and Griffis2009; Feyereisen et al., Reference Feyereisen, Camargo, Baxter, Baker and Richard2013; Shao et al., Reference Shao, DiMarco, Richard and Lynd2015; Malone et al., Reference Malone, Obrycki, Karlen, Ma, Kaspar, Jaynes, Parkin, Lence, Feyereisen, Fang, Richard and Gillette2018), and government initiatives like the US Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS2) call for increasing the production of cellulosic biofuels from crops like winter rye (EPA, 2022). Agricultural biomass similar to winter rye is used for bioenergy production from anaerobic digestion in several countries outside the US (Valli et al., Reference Valli, Rossi, Fabbri, Sibilla, Gattoni, Dale, Kim, Ong and Bozzetto2017; Theuerl et al., Reference Theuerl, Herrmann, Heiermann, Grundmann, Landwehr, Kreidenweis and Prochnow2019; Kemausuor et al., Reference Kemausuor, Adaramola and Morken2018). Industrial scale renewable natural gas facilities using agricultural residues as their feedstock are operating in the North Central US (e.g., https://www.verbio.us/project/verbio-nevada-biorefinery/), and interest is growing for these systems to produce biogas from agricultural biomass and convert it into renewable natural gas (Pleima, Reference Pleima2019). Herbstritt et al. (Reference Herbstritt, Richard, O'Brien, Emmett, Karlan, Kasper, Kohler, Wu, Lence and Malone2022) reported the revenue potential of the winter rye collected in this current study as a feedstock for these digestor systems, which included using the digestate as a feed protein supplement. Since the market for winter rye as an energy feedstock is currently limited in the US, our economic analysis focused on breakeven prices rather than revenue and compared these breakeven prices to current market prices for hay and potential prices for the cellulosic bioenergy market.

Energy budgets and greenhouse gas emissions using FEAT

Energy inputs per hectare were the lowest for the unfertilized treatments and the highest for the 120 kg N ha−1 fertilizer treatments in both years (Table 3). In 2018, energy outputs were similar between the fertilizer rates (Table 3), while in 2019 the 60 and 120 kg N ha−1 treatments resulted in higher energy output than the unfertilized treatment. The average annual energy output of approximately 117 GJ ha−1 for the N rate of 60 kg ha−1 is similar to rye silage reported by Camargo et al. (Reference Camargo, Ryan and Richard2013) of slightly more than 100 GJ ha−1. The calculated annual energy input (5.5 GJ ha−1) is lower than the Camargo et al. (Reference Camargo, Ryan and Richard2013) estimate of approximately 10 GJ ha−1, partly because we did not include additional lime, herbicide, insecticide or tillage. The current calculated energy inputs were closer to the double-cropping fertilized camelina-soybean system of 7.1 MJ ha−1 reported by Gesch et al. (Reference Gesch, Archer and Berti2014) when subtracting the soybean-related energy inputs.

The net energy associated with the rye management in the double-cropping system was positive in both years for all treatments (greater than 55 GJ ha−1) when accounting for the estimated 2019 reduced soybean yield. Averaged over both years, net energy values were 84 and 104 GJ ha−1 for the unfertilized and 60 kg N ha−1 rates (and were significantly different). In contrast, net energy of double-cropping soybean systems with winter camelina were reported 53 GJ ha−1 lower than soybean-only systems (Gesch et al., Reference Gesch, Archer and Berti2014). The main differences in the net energy of the two studies were the high soybean yield reductions of 2.0 Mg ha−1 and lower camelina yield of approximately 1.2 Mg ha−1 reported by Gesch et al. (Reference Gesch, Archer and Berti2014). They attributed the high soybean yield reduction mostly to the late seeding dates (30 June 2010 and 11 July 2011) relative to the conventional mono-cropping soybean (5 May 2010 and 19 May 2011).

The FEAT model predicted that N fertilization would lead to increased GHG emissions, which ranged from a low of 277 kg CO2-e to a high of 1931 kg CO2-e ha−1 year−1 in 2019 (Fig. 3). Direct N2O emission resulting from fertilizer application was the largest source of GHG, totaling 450 and 899 kg CO2-e ha−1 year−1 in the 60 and 120 kg N ha−1 treatments (Fig. 3). This estimate depends heavily on the choice of emission factors and is the largest source of uncertainty in estimating GHG impacts of fertilizer management in the double-cropping system. The geographic location and fertilizer application timing in early spring on wet soils support the higher emission factor of 1.6% for fertilizer application in wet climates. However, this effect may be offset by lower soil temperatures in spring, when the growing rye is expected to take up most of the additional N. In balance, the 1.6% emission factor may overestimate emissions as statistical modeling studies of soybean relay-cropping systems suggest a much lower emission factor (Cecchin et al., Reference Cecchin, Pourhashem, Gesch, Lenssen, Mohammed, Patel and Berti2021).

Fig. 3. Predicted (FEAT model) greenhouse gas emissions as CO2-equivalents from management of the rye-soybean double-cropping system under alternate rye planting methods and fertilizer N application rates. For each growing season, 2018 and 2019, data are reported by rye planting method (drilled after corn harvest, broadcast and overseeded into R6 corn, and broadcast and incorporated after corn harvest) and by fertilizer N application rate (0, 60 and 120 kg N ha−1). Average rye biomass yield and N content for each treatment from each year were used for this analysis.

Energy required to manufacture the N fertilizer (234 and 469 kg CO2-e) was the second greatest source of GHG. Increased biomass production resulting from N fertilization did not offset these emission sources, and GHG intensity (kg CO2-e GJ−1 output) increased with each fertilizer rate in both years. In 2018, GHG intensity was 3.1, 9.7 and 18.2 kg CO2-e GJ−1 output at 0, 60 and 120 kg N ha−1, and in 2019 GHG intensity was 4.0, 10.5 and 15.8 kg CO2-e GJ−1 output at 0, 60 and 120 kg N ha−1.

The FEAT model estimates N2O emissions resulting from N contained in plant residues returned to the field. In this case, residues included N contained in the rye stubble and the N contained in below-ground residues, which were estimated as a percentage of above-ground biomass based on default values in the FEAT model. Rye residues were predicted to contribute substantially to direct and indirect N2O emissions in all systems, averaging 143–206 kg CO2-e depending on biomass production. However, the IPCC emission factors likely overestimate rye residue contribution to N2O production. Residues with higher C:N ratio, such as rye, are likely to immobilize inorganic N during decomposition and unlikely to contribute to increased N2O emissions (Charles et al., Reference Charles, Rochette, Whalen, Angers, Chantigny and Bertrand2017). In a 10-year study on a similar soil type, Parkin et al. (Reference Parkin, Kaspar, Jaynes and Moorman2016) found no increase in N2O emission associated with rye that produced less than 2.0 Mg ha−1 in corn-soybean rotations. Rather, rye led to a non-statistically significant decrease in N2O emissions. Moreover, rye decreased leaching by 192 kg ha−1 and correspondingly decreased estimated indirect N2O emissions by 1.44 kg N2O-N over the 10 years. Similarly, Machado et al. (Reference Machado, Farrell, Deen, Voroney, Congreves and Wagner-Riddle2021) found that residue contribution to N2O emissions never exceeded 0.1% in diversified and conventional cropping systems.

Thus, our estimates likely overestimate the burden and underestimate the ecosystem services provided by the double-crop CC in terms of GHG emissions. However, yield benefits from fertilizer application in the rye phase may be evaluated against potential for increased GHG emissions from the system.

Conclusions

Over the 2-year study in the North Central US, we found that double-cropping soybean with winter rye CC showed promise to increase overall production per unit land area. We found that planting method did not consistently affect any metrics included in this study, suggesting that this double-cropping system can be successfully implemented in a variety of ways when conditions are favorable for CC production. Fertilizing the rye double-crop CC at 60 kg N ha−1 was economically competitive with no fertilizer application over the 2-year study, produced more biomass, had higher net energy and had more N removed with harvest than applied. However, increasing the fertilizer rate to 120 kg N ha−1 did not increase biomass production or N accumulation enough to offset increases in N rate. Further research into fertility management of rye within the double-cropping soybean system will improve the efficiency of these systems, as our findings indicated that landscape position and year may have played roles in biomass production response to N fertilizer. Additionally, further research into downstream markets like sustainable bioenergy may offset GHG emissions from N fertilizer and improve these systems overall carbon balance and environmental benefit, as reported by Herbstritt et al. (Reference Herbstritt, Richard, O'Brien, Emmett, Karlan, Kasper, Kohler, Wu, Lence and Malone2022). Sustainable bioenergy systems can remove carbon from the atmosphere through terrestrial sequestration and bioenergy carbon capture and storage (Sanchez et al., Reference Sanchez, Nelson, Johnston, Mileva and Kammen2015; Field et al., Reference Field, Richard, Smithwick, Cai, Laser, LeBauer, Long, Paustian, Qin, Sheehan, Smith, Wang and Lynd2020). Overall, including rye in a double-cropping soybean system to intensify agricultural production can be economically and environmentally viable in the North Central US.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the essential assistance of B. Knutson, O. Smith, D. Carney, A. Morrow and numerous student workers for establishing the site, collecting data, conducting sample analysis and managing the field plots. This research was supported by the US Department of Energy under the Bioenergy Technologies Office, award number EE0007088. The USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Mention of trade names or commercial products in this article is solely for the purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the USDA.

Conflict of interest

None.