Introduction

Adequate fruit and vegetable (FV) intake is critical for optimal health and reduces the risk of diet-related diseases such as cardiovascular disease, cancer and diabetes (Carter et al., Reference Carter, Gray, Troughton, Khunti and Davies2010; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Ouyang, Liu, Zhu, Zhao, Bao and Hu2014; Aune et al., Reference Aune, Giovannucci, Boffetta, Fadnes, Keum, Norat, Greenwood, Riboli, Vatten and Tonstad2017). Americans typically under-consume fruits and vegetables (Krebs-Smith et al., Reference Krebs-Smith, Guenther, Subar, Kirkpatrick and Dodd2010; Moore et al., Reference Moore, Dodd, Thompson, Grimm, Kim and Scanlon2015; Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Reedy and Krebs-Smith2016) with only 12.2% meeting fruit intake recommendations and 9.3% meeting vegetable intake recommendations in 2015 (Lee-Kwan et al., Reference Lee-Kwan, Moore, Blanck, Harris and Galuska2017). From 2007 to 2010, 60% of children did not meet fruit intake recommendations and 93% did not meet vegetable intake recommendations (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014). Direct farm-to-consumer interventions such as community-supported agriculture (CSA) programs have been suggested as one strategy to increase FV intake (Khan et al., Reference Khan, Sobush, Keener, Goodman, Lowry, Kakietek and Zaro2009). CSA programs traditionally involve community members paying for a ‘share’ of a local farm's crops at the beginning of the farming season and receiving a weekly (or biweekly) portion of the harvest throughout the growing season. CSA participation has been linked to increased FV intake and other positive behavioral and health outcomes (Minaker et al., Reference Minaker, Raine, Fisher, Thompson, Van Loon and Frank2014; Vasquez et al., Reference Vasquez, Sherwood, Larson and Story2016; Allen et al., Reference Allen, Rossi, Woods and Davis2017). Allen et al. (Reference Allen, Rossi, Woods and Davis2017) found that CSA participants reported a decrease in eating out at restaurants, less processed food intake while in the car, eating healthier foods such as salads and increased FV intake. Before participating in the CSA, the mean self-reported FV intake was 4.55 servings per day, and after, the mean intake was 7.22 servings (P < 0.001) (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Rossi, Woods and Davis2017). In a separate study, CSA participants reported that after joining a CSA, there were more vegetables present in the household, more frequent family meals, fewer fast food and restaurant meals, and increased FV intake (Vasquez et al., Reference Vasquez, Sherwood, Larson and Story2016). However, weekly CSA participation was not significantly associated with FV variety or intake (Vasquez et al., Reference Vasquez, Sherwood, Larson and Story2016).

Besides potential public health benefits, interest in marketing systems that directly connect farms and consumers, including farmers' markets and CSA, has grown across the USA, Canada and Europe in recent decades (Renting et al., Reference Renting, Marsden and Banks2003; Galt, Reference Galt2011). However, participation in these marketing systems is unequal, with higher-income participants more likely to participate than lower-income individuals, which hinders the role that CSAs could play in addressing health disparities (Galt et al., Reference Galt, Bradley, Christensen, Fake, Munden-Dixon, Simpson, Surls and Van Soelen Kim2017; Vasquez et al., Reference Vasquez, Sherwood, Larson and Story2017). The upfront cost may be a key barrier to participation for low-income individuals (Andreatta et al., Reference Andreatta, Rhyne and Dery2008; White et al., Reference White, Jilcott Pitts, McGuirt, Hanson, Morgan, Kolodinsky, Wang, Sitaker, Ammerman and Seguin2018; McGuirt et al., Reference McGuirt, Pitts, Hanson, DeMarco, Seguin, Kolodinsky J, Becot and Ammerman2020), who are also most at risk for low FV intake (Grimm et al., Reference Grimm, Foltz, Blanck and Scanlon2012).

To address the cost barrier, some farms offer a cost-offset (CO) using a diversity of financing mechanisms. In a previous study, farmers reported that they needed to raise between $650 and $4800 (average of $2468) per season to fund the CO for a CSA, depending on the number of subsidized shares offered and percent of the market share price to be subsidized (Sitaker et al., Reference Sitaker, McCall, Kolodinsky, Wang, Ammerman, Bulpitt, Jilcott Pitts, Hanson, Volpe and Seguin-Fowler2020b). Furthermore, most farmers reported that they initially planned to use member donations as the primary mechanism to offset the CSA cost, yet some had to scale back their funding plans due to pressing work demands on their farms (Sitaker et al., Reference Sitaker, McCall, Kolodinsky, Wang, Ammerman, Bulpitt, Jilcott Pitts, Hanson, Volpe and Seguin-Fowler2020b). Several studies have described the funding of CO-CSA through grants or other external funding sources (Quandt et al., Reference Quandt, Dupuis, Fish and D'Agostino2013; Izumi et al., Reference Izumi, Higgins, Baron, Ness, Allan, Barth, Smith, Pranian and Frank2018; Berkowitz et al., Reference Berkowitz, O'Neill, Sayer, Shahid, Petrie, Schouboe, Saraceno and Bellin2019). However, to increase the sustainability of CO-CSA programs, the feasibility of a variety of funding mechanisms should be considered, ranging from full-paying CSA member donation, tiered cost structures, philanthropic fundraising, or use of CO-CSA's members' Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits (SNAP/EBT) (Sitaker et al., Reference Sitaker, McCall, Kolodinsky, Wang, Ammerman, Bulpitt, Jilcott Pitts, Hanson, Volpe and Seguin-Fowler2020b) as well as matching programs for SNAP (e.g., Double-up Bucks). While we have previously reported on farmer opinions concerning the benefits and challenges of various funding mechanisms (Sitaker et al., Reference Sitaker, McCall, Belarmino, Wang, Kolodinsky, Becot, McGuirt, Ammerman, Jilcott Pitts and Seguin-Fowler2020a, Reference Sitaker, McCall, Kolodinsky, Wang, Ammerman, Bulpitt, Jilcott Pitts, Hanson, Volpe and Seguin-Fowler2020b), it remains unclear which of these mechanisms is most sustainable for farmers implementing a CO, and most desirable for the full-pay CSA members who may help subsidize the CO. A recent environmental scan of CO-CSA programs throughout the USA found that the sliding scale was the most widely used funding mechanism (Sitaker et al., Unpublished manuscript, Reference Sitaker, McCall, Vaccaro, Wang, Kolodinsky, Jilcott Pitts, Hanson, Volpe and Seguin-Fowler2020c). Furthermore, about three-fourths relied on individual farms to manage the funding for the off-set cost, and the remaining fourth of CO-CSA programs were operated by a third party (Sitaker et al., Reference Sitaker, McCall, Kolodinsky, Wang, Ammerman, Bulpitt, Jilcott Pitts, Hanson, Volpe and Seguin-Fowler2020b).

There is a need to increase our understanding of how we combine effective public health interventions with sustainable funding mechanisms. CO-CSA may be one approach to combining these dual goals. In this article, we begin to report on these research gaps by drawing on data from the Farm Fresh Foods for Healthy Kids (F3HK) intervention study which began in 2016 by offering a CO CSA, paired with nutrition education, for low-income households with children in four geographically diverse states (Seguin et al., Reference Seguin, Morgan, Hanson, Ammerman, Pitts, Kolodinsky, Sitaker, Becot, Connor, Garner and McGuirt2017). One major aim of the project was to better understand how to sustain the project after the end of grant funding. Thus, in this article, we describe the feasibility of various mechanisms to sustain the CO portion of the project, from both the farmer and full-pay CSA member perspectives. In particular, we qualitatively explore experiences and perceptions of CSA farmers and CSA members to help identify: (1) benefits and challenges of running a CO-CSA program for low-income families; (2) strategies for funding the CO including support for and opposition to potential funding channels; and (3) lessons learned from farmers who have run a CO-CSA program. To our knowledge, this is the first study that asks CSA shareholders to provide their own perspectives of the benefits and challenges of various CO-CSA funding methods.

Methods

Participants and recruitment

In-depth interviews with CSA farmers and CSA members, herein referred to as ‘farmer’ and ‘member,’ were conducted as part of the formative evaluation phase of F3HK, a community-based, randomized intervention trial to examine the impact of subsidized or CO-CSA participation on dietary intake, quality and related outcomes among low-income families (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02770196). Additional details on the design and methods of the intervention are published elsewhere (Seguin et al., Reference Seguin, Morgan, Hanson, Ammerman, Pitts, Kolodinsky, Sitaker, Becot, Connor, Garner and McGuirt2017). Farmers and members were identified across four geographically diverse states: New York, North Carolina, Vermont and Washington. Farmers were recruited through cooperative extension referrals, our research teams' networks and Internet searches. Members of those CSA programs were sent a recruitment email and/or received a flyer placed in their CSA share or posted at the pick-up site.

Farmers were screened to determine whether they utilized a CO-CSA model, and two samples were selected: (1) CSA farm with a CO and (2) CSA farm without a CO. Twelve interviews were conducted in each group for a total of 24 farmer interviews, evenly dispersed across the four states. A total of 20 interviews with full paying members were conducted; five in each state. All participants were at least 18 years of age and spoke English. Farm profiles and member demographic characteristics can be found elsewhere (Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Severs, Hanson, McGuirt, Becot, Wang, Kolodinsky, Sitaker, Jilcott Pitts, Ammerman and Seguin2018).

Interviews with farmers were conducted over the phone and interviews with members were conducted in-person. Farmers provided verbal consent and members provided written consent. Farmers were compensated $50 and members were compensated $20. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Vermont [Protocol ID #15–442 (Farmer) and #16–213 (Member)] and Cornell University (Protocol ID #1501005266).

Interview guides

Two farmer interview guides were developed based on whether they operated a CO CSA or not. The questions in both guides paralleled one another with the primary difference being the way in which farmers were asked about the mechanisms for COs, specifically with regard to their experiences vs their perceptions. In addition to the mechanisms for COs, the interview guide included questions around CSA operations, marketing strategies, characteristics of CSA members and most popular produce which are discussed elsewhere (Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Severs, Hanson, McGuirt, Becot, Wang, Kolodinsky, Sitaker, Jilcott Pitts, Ammerman and Seguin2018).

In order to classify a farmer as a ‘farmer with a CO-CSA’ vs a ‘farmer without a CO-CSA,’ we asked farmers ‘Do you already have strategies in place to subsidize CSA shares for low-income consumers?’ However, after the interviews were conducted, our research team noted some inconsistencies in how this question was answered. For example, some farmers had informal CO mechanisms in place but responded ‘no’ while others had the same informal mechanisms in place but responded ‘yes.’ Also, some had offered CO-CSA in the past, but had stopped, and some farmers had used only one of the offset mechanisms but not the others. Consequently, we pooled interview data from all farmers for analysis.

The member interview guide included questions about food assistance programs, attitudes toward incorporating local foods into food assistance programs and mechanisms for COs. Additionally, members were asked to perform a contingent valuation exercise in which they were asked about willingness to financially support a CO-CSA. Participants were asked about both weekly and seasonal donation amounts. For each scenario, eight prices were offered (weekly $1, $2, $3, $4, $5, $8, $10, $12; seasonal $20, $40, $60, $80, $100, $160, $200, $240). Each price was asked until a maximum amount was identified. The mean and range for these reported donations were calculated [see McGuirt et al. (Reference McGuirt, Pitts, Hanson, DeMarco, Seguin, Kolodinsky J, Becot and Ammerman2020) for a longer discussion of a contingent valuation exercise with CO-CSA members]. The guide also contained questions on features of their CSA, CSA preferences, factors that influence their participation, their child's involvement in the CSA (if relevant) and food shopping preferences. These latter themes are included in a separate publication (Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Severs, Hanson, McGuirt, Becot, Wang, Kolodinsky, Sitaker, Jilcott Pitts, Ammerman and Seguin2018). Members were also asked to respond to a brief demographic survey including age, sex, race, ethnicity, education, household income and household composition.

The specific mechanisms for COs asked of both farmers and members included member donations, workshares, fundraising, grants and SNAP benefits. In order to elicit feedback on the use of member donations, farmers and members were asked slightly different questions. Farmers responded to the question, ‘Please share your thoughts on having your full-pay members pay extra as a cost-offset.’ Members were asked, ‘How much would you be willing to pay in addition to your produce box per week in order to make a produce box more accessible for a low-income person?’ Members were also provided a follow-up question, ‘Would you prefer a CSA that does an automatic sliding scale payment system based on income or one that allowed for voluntary donations?’ Due to the difference in questions asked, members attitudes toward voluntary donations and a sliding scale structure could be teased apart, whereas farmers typically discussed either voluntary donations or a sliding scale, but not both, so farmer feedback was grouped under one broader category referred to as ‘member donations.’ A workshare was defined as ‘an agreement where the customer would work a certain number of hours in return for a discounted CSA share.’ EBT was defined as ‘the electronic card payments that participants in the SNAP program – what we used to call the Food Stamp program – can use to purchase food.’ A definition was not provided for the use of grants or fundraising as a CO, and thus the participants self-defined these mechanisms. Although not explicitly defined, farmers and members almost always discussed these in the context of grant and fundraising efforts being initiated and managed by the farm. Farmer interviews lasted 32–146 min (median = 51 min) and member interviews lasted 34–87 min (median = 52 min). In order to ensure consistency across states, all interviewers were trained in protocols for recruitment and interview facilitation.

Qualitative data analysis

All interviews were recorded, transcribed verbatim and imported into NVivo version 11 (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia). Interviews of farmers and members were coded separately. Three member interviews and four farmer interviews were randomly selected and descriptively coded by the second and fifth authors. These authors met to discuss their initial coding and review their coding notes. All differences were discussed until consensus was reached. A codebook was generated and used to re-code the seven original interviews, and guide the remainder of coding, which was conducted by the fifth author. The second and fifth authors individually reviewed quotations within codes for each CO mechanism, and subsequently categorized them as ‘support,’ ‘neutral,’ or ‘opposition’ using magnitude coding. Thematic analysis was used subsequently to identify themes, with a focus on the benefits and challenges of operating a CO-CSA, mechanisms for funding a CO-CSA, and lessons learned from farmers who had previous experience with a CO-CSA.

Results

Farm and participant characteristics

Most of the farmers interviewed had been operating their CSA for at least 5 years (67%), with ten farms running their CSA for 10 years or longer. CSA membership ranged from 6 to 1200 members. Seven out of 24 farms (29%) had a waitlist for their CSA. Fourteen farms had <200 members while eight had ⩾200 members. For most farmers, their CSA was one of multiple revenue streams that included sales from farmers' markets and wholesale distribution. Of the 24 interviewed CSA farmers, 22 (92%) were selling their products at farmers' markets and/or wholesale, in addition to their CSA.

The members interviewed were primarily female (95%), white (100%) and had 4+ years of college education (83%). CSA members averaged 46.3 years in age. Nine of the 20 (45%) were in households with two adults and children, while 11 were in households with just two adults, no children. Thirteen of 18 (72%) participants reported household incomes of $50,000–$74,999, or higher. Forty percent of members had participated in CSA for over 5 years.

Perceived benefits and challenges of running a Co-CSA for low-income families

Overall, both farmers and CSA members had positive opinions of CO-CSA. Table 1 shows the perceived benefits and challenges of a CO CSA from the perspectives of farmers and full-pay members. These benefits and challenges are discussed in detail below.

Table 1. Perceived benefits and challenges of running a CO-CSA for low-income families from the perspective of CSA farmers and CSA members across four states

Access to healthy food

Sixty-three percent of farmers expressed a desire to make healthy food accessible to everyone, regardless of income level, and viewed this as a motivator for operating a CO-CSA program. Statements such as ‘I think healthy food is a human right,’ and ‘food should not be an elite thing’ were concepts shared by many. One farmer sympathized with those facing economic access barriers, noting ‘if I made the amount of money that I make now and decided I wanted to eat only local, organic produce, I couldn't afford it.’

Similarly, 45% of members conveying the belief that ‘everybody should have fresh, nutritious food.’

‘I think that's sort of a personal philosophy sort of question in that, you know, if you have enough, you need to make, do what you can to make sure other people have enough. Kids should not go to bed hungry at night.’—Member from North Carolina (NC), 02

Investment in community and society: The concept of CO-CSA was seen by both farmers and members as a positive way to invest in community and society (25 and 30%, respectively). Often, this was described as a small change that could have far-reaching impacts, such as one farmer who shared:

‘And obviously the pros are boundless in my mind. Yeah. Just it's a, it's a big picture thing. Just seems like getting everyone access to good food is really important for making change in our, in our world.’—Farmer from Vermont (VT), 02

Support for local farms: The potential to expand membership (and therefore farm revenue) was another benefit of CO-CSA cited by 29% of farmers. Fifteen percent of members felt similarly, expressing that CO-CSA is a ‘way for a farmer to then create a market for that produce.’ Members expressed the desire to support their local farmers and the greater community and viewed CO-CSA as a positive way to achieve that goal. As one member said:

‘I think it just makes sense. It goes with my whole equity thing. If I can, then I should. And I think it's a good investment in the people in my community: the recipients and then the farmers.’—Member, NC, 04

Administrative challenges for farmers: Sixty-seven percent of farmers were concerned about the administrative time required to initiate and maintain a CO-CSA program amongst their other farm demands. A few farmers were concerned about how to start and build a CO-CSA including ‘the organization of it all,’ and ‘not knowing where to start.’ However, farmers' primary concern was the management and administrative duties associated with collecting and tracking weekly CO-CSA payments. As one farmer shared:

‘just more administrative time… so that's more time that I'm not able to actually be farming, I have to really set aside time to do the paperwork.’—Farmer, NC, 02

Lack of members' interest, knowledge or skills: Seventeen percent of farmers and 65% of members mentioned that a lack of interest, knowledge and/or skills among low-income households could be a barrier to the success of CO-CSA. Some suggested that education might be needed regarding less familiar items found in CSAs. One member noted that unfamiliar produce may serve as a barrier to actual use and consumption, but noted that this issue is not necessarily limited to low-income individuals:

‘It's one thing to give people the vegetables, but if they don't know what it is, they're not gonna eat it. I mean, and there's plenty of people with more income who look at kale or swish chard, and they don't know what it is, and they don't wanna eat it. They don't know how to cook it, and so they don't eat it. So if like, you know…there's more to it than just providing the food items.’—Member from Washington (WA), 02

Mechanisms for funding a Co-CSA, including support and opposition of potential funding channels

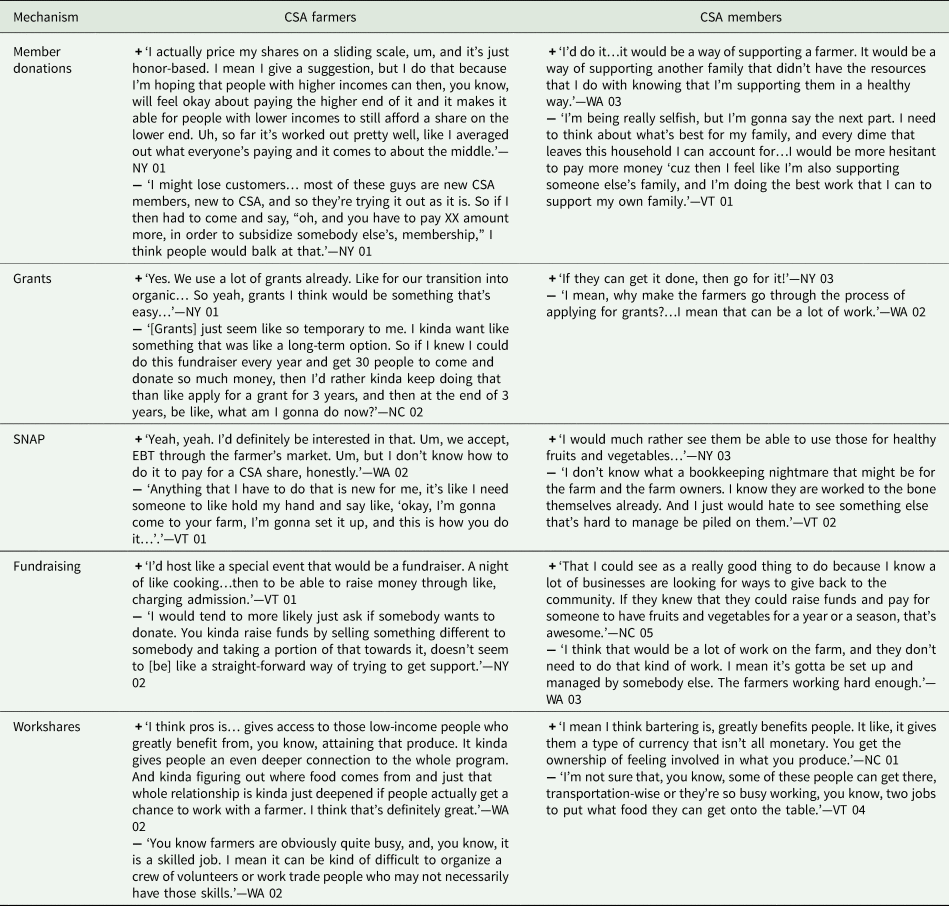

Figure 1 shows farmers and members' support and opposition to a range of strategies to offset the cost of CSA membership for low-income families. There was some support for all mechanisms; however, concerns around how the operationalization and implementation of these strategies were noted for all. Table 2 presents illustrative quotations in support and opposition of various funding channels.

Fig. 1. CSA member and CSA farmer support and opposition for CO-CSA funding mechanisms.

Table 2. Perceptions among CSA farmers and CSA members regarding CO-CSA funding mechanisms

Member donations

Member donation was the most supported mechanism by both farmers (63%) and members (80% supported voluntary donation and 58% also supported sliding scale; Fig. 1). Due to the open-ended nature of the question, farmers generally discussed member donations in the context of either voluntary donations (87%) or sliding scale (13%). Voluntary donations often involved farmers asking their members for donations and using those funds to partially or fully cover the cost of a share for families in need. A sliding scale is a payment structure in which higher income members pay a higher price for their CSA share, and lower income members pay a lower price. The ways in which these mechanisms were implemented were often unique to each farm. One farmer noted how a simple change in the CSA sign-up form tripled the donations received from full-pay members and another shared the structure they used for their sliding scale:

‘…on our membership form … in the past was a little blurb in the middle that said… ‘support <the CO-CSA program>. It provides scholarships for limited income families to join our farm. Make a donation!’ So this year, I'm like “I really wanna increase our farm donations.” I'm like, “I think I'm gonna change it and make it a line item where people are forced to put it in zero” [laugh] like for money. I didn't wanna make people feel bad, but…I felt like people weren't seeing it. So, I did that this year, and we like tripled our dollars. … it really worked.’—Farmer, VT, 01

‘…the full shares have always been on a sliding scale…so this year they're $495, $595, $695 or $795 depending on your perceived ability to pay. We don't check income, we don't do any of that stuff… it's honor system.’—Farmer from New York (NY), 03

According to this farmer, donations can be unpredictable. Relationship-building with donors is important in environments with competing calls for charitable giving:

‘It just takes time, I think, to build that relationship with a person or a group that is gonna donate. It's not something that can happen right away or that you should count on immediately.’—Farmer, NC, 01

Eighty percent of CSA members supported the use of voluntary member donations to help offset the cost of CSA shares for low-income individuals. Table 3 shows the amount members were willing to donate on a weekly vs seasonal basis, by income category. Seventeen of 20 participants were willing to donate, either in weekly installments or in a lump sum at the beginning of the season. On average, CSA members reported that they would be willing to donate a maximum of $4.22 weekly (range: $0–$12) or $50 per season (range: $0–$100). There appears to be a trend suggesting that higher annual income members may be willing to donate more money, especially when donating in a lump sum seasonally. Three members were not willing to personally contribute, and interestingly, these three members were spread over different income categories (Table 3). Reasons for not wanting to donate included other financial obligations, other causes that they already supported, or being ‘on the cusp’ themselves:

‘My initial thoughts are…you know, where do you draw the line for someone who can afford to pay extra versus someone who needs extra, because I, my family income is, like, on the cusp [laughs], where I can't really afford to help pay for somebody else, I can barely afford to pay for myself.’—Member, VT, 05

Fewer members were supportive of using a sliding scale for funding a CO-CSA (58%). Supporters of a sliding scale structure often liked being provided with guidelines and described this structure as being an innovative way to ‘frame where's a good place to be giving.’

‘I like the sliding scale…I don't know how that works, or how people feel about giving that much information about their income, but I think the sliding scale helps people understand their own fortune.’—Member, NC, 01

Forty-two percent of members opposed the use of a sliding scale or had mixed views. This opposition was primarily because they wanted choice and control, and therefore preferred to have the option of making a voluntary donation.

‘I feel like when things aren't mandatory, they tend to work better, so probably the voluntary.’—Member, NC, 04

‘I don't like having people have to prove that they're [low-income]… I hate having that income verification piece. I just think that that really is uncomfortable for people…. I think [if] I had to choose, I'd go the voluntary donation.’—Member, WA, 01

Table 3. Amount full-pay CSA members are willing to donate weekly and seasonally by household income

a Interviewer did not ask participant about willingness to donate on a weekly basis or seasonal basis; donations only in the context of one timeframe were discussed.

Grants

Farmers had mixed opinions about grants as a funding mechanism (33% support; 29% neutral; 38% opposition). Several mentioned that they would need help to start the process of finding and applying for grants, but nonetheless were interested in learning more about this mechanism. Many farmers also expressed concern around how time consuming this method could be alongside their other responsibilities. Some had concerns about the sustainability of this method for a long-term program.

‘…the pros would be…just another kind of thing in your corner … gettin’ those cost offset options out there. A…con being, … the kind of bureaucracy and paperwork that…as a farmer, that's usually not my favorite thing to do.’—Farmer, WA, 02

‘I think the only problem with grants …is that they come to an end. And … it needs to be kinda this self-sustained program, or it's this really cool thing for 3 or 5 years, and then it just kinda disappears. So I think they're a great idea as long as it…as it can be a thing that continues after the grant is done.’—Farmer, NY, 03

CSA members generally supported grants as a CO mechanism, but a few barriers emerged in the discussion of this method. The benefits include ‘kick starting’ CO programs for low-income families. Members generally thought it would be a great way to get a program like this off of the ground but, like farmers, were concerned with the sustainability of this short-term funding mechanism. Also a few members were concerned that farmers may not have the time to write grants amidst the other responsibilities that come with running their businesses.

‘I think grants--it's not like, definitely not a sustainable model for long-term but I think initially to get a farm to help with cost offset can be really helpful especially, too, if you're trying to get more private charitable donations. If you had like a grant to begin with to show like, “Look at this. Like what we can do with just this amount of money, it's a like of a good fundraiser for the future”.’—Member, NC, 05

‘’Cuz farmers probably don't have time to do it.’—Member, NC, 04

SNAP/EBT benefits

Farmers had no opposition to accepting SNAP benefits, but most expressed concerns about the difficulty or uncertainty of incorporating SNAP into their business models.

‘I don't really understand how to go about getting set up on that.’—Farmer, NC, 01

‘It's sort of a pain in the butt, the way they have to do it, because it's not something that's necessarily designed to work well with the CSA model.’—Farmer, NY, 01

‘Actually, two of my… EBT “bonus bucks” people never even paid me in full last year. [laugh] All they had to do was pay 8 dollars and 60 cents a week [laugh] and technically by my program, every other week, should be having 17 dollars debited from their EBT card for a small share. Apparently that might be too much for some people.’—Farmer, NY, 02

Several farmers mentioned that they accepted EBT through the farmers' market but not through their CSA.

‘Yes. I am interested in that. For right now, the way we can do that is through our farmers’ market. All the farmers’ markets we sell at have the swipe machine and are approved…’—Farmer, WA, 03

Some concerns included not knowing how to become authorized to accept SNAP, the length of time it would take to get authorized, and the logistics of its use after it was implemented. These quotations illustrate confusion about the logistics of the use of SNAP/EBT for a CSA:

‘You can also now use it (SNAP/EBT) for CSA. It's a pretty recent thing. You don't need to have….the electronic machine…it's like carbon copy. And then there's a logging system that you go online and say, this person, you know bought that much.’—Farmer, VT, 01

‘We didn't have enough volume to have, have one of those machines… Lately we've had food stamps members every year. But there was a while where no one with food stamps wanted to sign up….they really didn't want you having one of those machines unless you're doing regular business, so we didn't have one. We use paper. And it, it works fine. As long as they don't take them away from us [laugh]. There was some debate as to whether they wanted everything to go electronic. But [for] farmers at farmers’ markets and also some of us CSA people, it's the only thing we can use.’—Farmer, NY, 03

A few farmers were concerned with how payments would work, especially since members usually pay in advance of the season. Many requested additional information about SNAP/EBT, so that they could explore this option further.

Members mostly supported the use of SNAP benefits for the purchase of CSA shares. Some cited challenges with this method including burdening already busy farmers with extra logistics and bookkeeping.

Fundraising

Farmers were also divided in their opinions of fundraising as a CO mechanism; an equal number cited positive and negative perceptions. Most farmers spoke of fundraising in terms of hosting an on-farm event such as a catered or potluck dinner, or a barn dance.

‘It's a lot of work. We're having a pig roast at the farm in July to fundraise for Farm Fresh. It'll be fun and interesting and a lot of people will be there.’—Farmer, NC, 01

‘It's just a dinner. Food and music and drinks and an auction. Yeah, it was really nice. It was…a “Thanks for Giving” fundraiser is what it's called. It's the weekend before, the Saturday before Thanksgiving. And we did it at the [community center] which was really nice…’—Farmer, NC, 01

Some farmers saw fundraising as a time-consuming and unsustainable way to get support. Many said that they do not have the bandwidth or time to plan and execute a fundraiser.

CSA members voiced the most disapproval for fundraising as a CO mechanism. Many perceived it to be too burdensome for farmers to plan and execute amidst their other commitments. Some members viewed fundraising activities as overdone and had a cynical perspective toward the potential of fundraising:

‘I think that would be a lot of work on the farm, and they don't need to do that kind of work. It's gotta be set up and managed by somebody else. The farmer's workin’ hard enough.’—Member, WA, 03

‘Ugh. I'm so sick of fundraising. I would say last on the list. Last.’—Member, VT, 03

However, a few believed that it could be a fun and educational way for the community to connect around a good cause.

‘A lot of businesses are looking for ways to give back to the community. If they knew that they could raise funds and pay for someone to have fruits and vegetables for a year or a season, that's awesome.’—Member, NY, 03

Workshares: Farmers were at best, skeptical and at worst, opposed to funding a CO-CSA through workshares. While some farmers had experience with workshares, many others had never tried it, yet felt that it would not work well for their business. Some of the cited challenges included people not following through with their commitment, not possessing the needed skills, training and management, uncertainty around liability and labor regulations, and the lack of time that many low-income families already face.

‘I didn't have to have workers’ compensation. And I couldn't find anything that told me, if somebody was coming and helping you pick and you weren't paying them, or they were like share picking or something like that, if that went towards your worker's comp. ‘Cause it was in my mind, “wow this is gonna have to make me pay for insurance, I don't know if I can afford [laugh] somebody to come and help pick”.’—Farmer, NY, 02

‘There's certain jobs that, especially certain harvesting jobs, that we know members can handle, and certain ones we don't want them to do … things that are very delicate’—Farmer, NY, 03

‘Yeah we, we've had some trouble with that in the past. Because people will say, oh I wanna trade a CSA share for work. And we're like okay. And then they're like, I can only come Sunday these hours. Or Tuesday at, for 2 h after work … And it is not really convenient for what we need to get done. So it feels more like we're trying to figure out their schedule, than them working with ours.’—Farmer, VT, 01

‘…there's a lot of families who are working a lot of jobs. And I just don't think it's fair that we ask people who can't afford things to give up their time.’—Farmer, VT, 01

Workshares seemed to work best when farms were selective about which members were allowed to participate, and who limited the number of workshares offered. Finally, several farmers mentioned that they trade services rather than farm labor, not necessarily for low-income households only. Some of the services traded included website development, construction, excavation and electrical work.

CSA members generally supported workshares as a CO mechanism. The benefits of this mechanism went beyond just the CO, with some members thinking that working for their food would help low-income households build a connection to the farm and facilitate learning and education. However, lack of time and transportation emerged as barriers that might make workshares challenging for low-income households including one member who said ‘a lot of low-income households are really busting [their butts] as it is.’

‘So I think, you know, it, it, it sounds like a great idea to get ‘em involved, and I think it's something that really should be tried, but, I'm not sure that, you know, some of these people can get there, transportation-wise or they're so busy working, you know, two jobs to put what food they can get onto the table.’—Member, VT, 04

‘I think if there's that investment from the individual who's going to receive it, um, I think that's really important in helping the…I guess it's the CSA box go further and having an impact because there not just like being given it, it's like they have to work a little bit more for it.’—Member, NC, 05

Lessons learned from CSA farmers who have run a subsidized CSA program

Farmers who reported offering a CO-CSA shared general implementation lessons learned. Recruitment and selection of CO-CSA members was one component that several farmers discussed. Finding low-income participants who would be vested in and benefit from a CSA was a priority. Partnering with community organizations was described as helpful because ‘care managers and outreach workers were able to recommend people,’ and this helped connect eligible community members to the farm while taking the burden of advertising and promoting the program off the farmers. One farmer recalled that they switched their model from a ‘free share’ to a ‘cost share’ and noticed that the financial investment from these CO-CSA members resulted in ‘more serious participants.’

A few farmers talked about the CSA model being a poor fit for some, especially the ‘really, really low-income, at-risk people.’ The CSA model was designed so that members share both the benefits, as well as the risks, with the farmer, and some individuals are so strained financially that they cannot take on that risk.

Discussion

This research contributes new evidence to inform strategies to make CSA programs more inclusive to consumers across the economic spectrum while making the funding mechanisms more sustainable. The interviewed farmers' support for offering a CO-CSA program appeared to stem from their values, which included a belief in access to healthy food for all and giving back to the community. This agrees with prior literature (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2007; Galt et al., Reference Galt, O'Sullivan, Beckett and Hiner2012). We found that members expressed similar values and support for CO-CSA programs. Yet as noted in another study (Sitaker et al., Reference Sitaker, McCall, Belarmino, Wang, Kolodinsky, Becot, McGuirt, Ammerman, Jilcott Pitts and Seguin-Fowler2020a), farmers and members were concerned that a CO-CSA operation might require increased time to manage transactions, track payments and follow up on missed pick-ups, taking time from the urgent needs of farm management that must take precedence. We found member donations to be the CO-CSA funding mechanism most widely supported by both farmers and members. For farmers, this may be because member donations require modest effort on their part and leverages members' dedication to the CSA model (Sitaker et al., Reference Sitaker, McCall, Kolodinsky, Wang, Ammerman, Bulpitt, Jilcott Pitts, Hanson, Volpe and Seguin-Fowler2020b), which is enhanced by the farmer–member relationship that has been developed over time. A recent environmental scan of CO-CSA programs throughout the USA counted sliding scale funding separately from member donations and found sliding scale to be the most widely used funding mechanism (Sitaker et al., Unpublished Manuscript, Reference Sitaker, McCall, Vaccaro, Wang, Kolodinsky, Jilcott Pitts, Hanson, Volpe and Seguin-Fowler2020c). In the current study, the CSA members that we interviewed preferred the option of voluntary donations over a sliding scale because they valued having choice and flexibility in their donations. One farm in our study utilized a voluntary sliding scale where price points were given as guidelines, or suggestions, but were not mandatory. This voluntary sliding scale system may be viewed as a more appealing model by members who like to have some autonomy over their donation.

Full-pay members seemed somewhat supportive of workshares, because they saw additional benefits of enabling low-income families to contribute toward the cost of their share while developing closer ties to their farm. However, farmers did not favor this mechanism, which is in line with previous research (Woods et al., Reference Woods, Ernst, Ernst and Wright2009); they felt that managing untrained volunteers would require additional time and skills and necessitate dealing with additional liability issues and work regulations. The low interest in workshare similar to previous CSA work-share relationships can have many of the characteristics of an employee/employer relationship (Pennsylvania Association For Sustainable Agriculture, 2012) and may be subject to labor laws. Labor laws were in the forefront of many farmers' minds, which could be due to an increased in labor law enforcement by the Department of Labor (Kalyuzhny, Reference Kalyuzhny2012); therefore, workshares may be a less viable option than in past years. Workshares, while perhaps successful in the past, are not currently likely to be socially or economically sustainable.

Grants and fundraisers were moderately received by farmers and members. Farmers and members saw drawbacks to grants and fundraisers, due to the additional paperwork and planning required of the farmer. Additionally, some members thought that fundraising was ‘overdone.’ If grants and fundraisers are pursued by more farmers, additional supports, perhaps through the local cooperative extension, and online resources and workshops could be offered to ensure farmers have help in writing grants and ultimately operationalizing these CO mechanisms (McGuirt et al., Reference McGuirt, Pitts, Seguin, Bentley, DeMarco and Ammerman2018).

Farmers and members both supported the use of SNAP to help low-income members pay for a CSA share. For farmers, the procedures for accepting SNAP were largely unknown and somewhat daunting. A CSA member using their SNAP benefits may pre-pay a maximum of 14 days prior to pick-up (United States Department of Agriculture 2015); thus, farmers need to manage weekly or bi-weekly payment plans. This deviates substantially from the traditional CSA model in which members pay for their share upfront prior to the start of the season and share some financial risk alongside the farmer. At the same time, while there are administrative burdens associated with SNAP, the use of SNAP greatly reduces the burden of fundraising for farmers. Furthermore, SNAP is the largest food assistance program in the USA, with rules that are largely similar across states. This provides important opportunities to further leverage SNAP and to develop technical assistance resources for farmers that could be used more broadly. For low-income members, acceptance of SNAP may make the purchase of a CSA more feasible, but does not actually reduce or offset the cost. The full price of a CSA, even if purchased with SNAP benefits, may still be out of reach for low-income individuals pointing to the importance of additional financial support for low-income households such as double-up bucks programs, which are discussed further below.

The CO-CSA model holds promise as a strategy to remove access barriers to locally grown produce and increase FV consumption among low-income adults (Quandt et al., Reference Quandt, Dupuis, Fish and D'Agostino2013; Izumi et al., Reference Izumi, Higgins, Baron, Ness, Allan, Barth, Smith, Pranian and Frank2018; Berkowitz et al., Reference Berkowitz, O'Neill, Sayer, Shahid, Petrie, Schouboe, Saraceno and Bellin2019; Seguin-Fowler et al., Reference Seguin-Fowler, Hanson, Jilcott Pitts, Kolodinsky, Sitaker, Ammerman, Marshall, Belarmino, Garner and Wang2021). Potential collateral benefits include connections to the land and the farmers who grow the food, as well as participation in a community of residents that appreciates local agriculture (Hanson et al., Reference Hanson, Garner, Connor, Jilcott Pitts, McGuirt, Harris, Kolodinsky, Wang, Sitaker, Ammerman and Seguin2019). Yet CO-CSA as a mechanism to improve food security remains tenuous. Few farmers interviewed for this study had support from community partners in operating their CO-CSA program. Further, many small and medium-sized farms operationalize their support for greater inclusivity in access to healthy food by charitably contributing their time and products to support a CO-CSA. This was true of some of the farmers we interviewed, who sometimes subsidized CSA share prices claimed not to operate a CO-CSA program. A national scan of CO-CSA programs estimated that 75% rely on the individual farms to manage and find funding for the off-sets (Sitaker et al., Unpublished Manuscript, Reference Sitaker, McCall, Vaccaro, Wang, Kolodinsky, Jilcott Pitts, Hanson, Volpe and Seguin-Fowler2020c). The remaining 25% of CO-CSA programs were operated by third party entities specifically designed to focus on building a diverse funding and outreach strategy, implemented by skilled, designated staff and involving one or more farms (Sitaker et al., Reference Sitaker, McCall, Kolodinsky, Wang, Ammerman, Bulpitt, Jilcott Pitts, Hanson, Volpe and Seguin-Fowler2020b). While seldom discussed, there is a need to question the extent to which the CO-CSA model is socially or economically sustainable for farmers. Previous research has pointed to the challenges of making of living in agriculture, in particular for small-scale operations that engage in direct-to-consumer market channels (Pilgeram, Reference Pilgeram2011; Weiler et al., Reference Weiler, Otero and Wittman2016; Bruce and Castellano, Reference Bruce and Castellano2017).

The CO-CSA model could be further strengthened and supported through federally funded programing. Several reports demonstrate successful outcomes for programs that incentivize the use of SNAP benefits at direct-to-consumer venues. The Double-up Food Bucks program, which provides additional benefits to SNAP recipients for each dollar spent at farmers' markets, has been shown to increase the use of farmers' markets and self-reported FV intake (Young et al., Reference Young, Aquilante, Solomon, Colby, Kawinzi, Uy and Mallya2013; Dimitri et al., Reference Dimitri, Oberholtzer, Zive and Sadolo2015; Olsho et al., Reference Olsho, Payne, Walker, Baronberg, Jernigan and Abrami2015; Durward et al., Reference Durward, Savoie-Roskos, Atoloye, Isabella, Jewkes, Ralls, Riggs and LeBlanc2019). However, Double-Up Food Bucks program participation is low, with one study indicating that 5% of SNAP enrollees participated in double-up bucks programming (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Lachance, Richardson, Mahmoudi, Buxbaum, Noonan, Murphy, Roberson, Hesterman, Heisler and Zick2018). This low participation rate suggests that additional barriers to the use of such programs must be overcome. An alternative might be to expand the USDA Local Foods Promotion Program to provide federal funding to CO-CSA programs. In combination with programming operated by third party entities, and additional support from community partners, federal funding would help bring the CO-CSA model to scale, to the benefit of farmers and low-income participants alike.

The study limitations include overlap between the samples of CSA farms with and without CO-CSA programs: several farmers stated they did not have a CO CSA but during the course of the interview it became clear that they had some prior or current experience offering subsidized CSA shares. These blurred lines made it impossible to examine differences between the perspectives of farmers with and without a CO CSA. Second, the members may have been most supportive of member donations because it is the offset mechanism with which they were most familiar. Finally, we did not include perspectives of the CO-CSA recipients themselves. However, in a prior study, we reported on the perspectives of the participants receiving the CO (White et al., Reference White, Jilcott Pitts, McGuirt, Hanson, Morgan, Kolodinsky, Wang, Sitaker, Ammerman and Seguin2018), which suggested that more flexible pick-up times and choice of produce in the shares enhanced the benefits of the CO-CSA program. This study also has several strengths, including an in-depth focus on farmers and members, important stakeholders in any CO-CSA. To our knowledge, this is the first study that asks members to give their opinions of the pros and cons of various CO-CSA funding methods.

Conclusions

Of the mechanisms we explored, only donations from full-pay members were broadly supported by both farmers and members. Therefore, CO-CSAs based upon donations from full-pay members should ensure that members are invested in the idea. The idea of using SNAP/EBT for CO-CSA is another appealing mechanism for farmers and members, but more work should be done to ensure that this model is easy to implement and sustain. Innovative policies, such as incorporating concepts of the Double-Up Food Bucks model and CO-CSA, should be explored in future studies.

Based upon data from Sitaker et al., the average amount estimated by farmers to fund their CO-CSA was $2468 per season for the CO (Sitaker et al., Reference Sitaker, McCall, Kolodinsky, Wang, Ammerman, Bulpitt, Jilcott Pitts, Hanson, Volpe and Seguin-Fowler2020b). On average, the members we interviewed reported that they would be willing to pay an extra $50 per season to help others afford a CSA membership. Therefore, around 51 full-pay members would need to give $50 to make the average CO-CSA work financially. Toolkits have been developed to help farmers consider how to start a CO CSA program (Wholesome Wave, 2014; Sitaker, Reference Sitaker2018). Future research should investigate the implementation of these various CO-CSA operational models in order to determine which models are most economically viable and sustainable for both the farmers and consumers. More broadly, future research should examine the extent to which models that rely on the goodwill of farmers and customers can be sustainable in the long-term and should assess the ethical and policy implications of individual responses to the larger structural challenges associated with poverty and the ability to purchase a healthy diet.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the CSA farmers, their staff and the CSA members who participated in the study.

Author contributions

RSF, SJP, KLH, JK, ASA and MS conceptualized and designed the research study, oversaw intervention implementation and data collection, and revised the manuscript for important content; SJP and LCV drafted the paper and made final revisions. LCV and AS analyzed data. LCV, JTM, WW, EHB, AS and FB contributed to data collection and analysis, and revised the manuscript for important content. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Financial support

This research was supported by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), under award number 2015-68001-23230. USDA had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article.

Conflict of interest

None.