A poor diet is associated with four major non-communicable diseases: cancer, CVD, diabetes and respiratory disorders( Reference Aburto, Ziolkovska and Hooper 1 – Reference Walda, Tabak and Smit 4 ), which account for approximately 60 % of deaths globally per annum( Reference Cecchini, Sassi and Lauer 5 ). There is a growing body of research which highlights the benefits of fruit and vegetable (F&V) consumption, including the protective effect of F&V consumption on CVD( Reference Dauchet, Amouyel and Hercberg 6 , Reference Joshipura, Hu and Manson 7 ). The WHO Global Strategy on Diet and Physical Activity has made several key recommendations with respect to dietary intake, including increasing F&V consumption( Reference Waxman 8 ). In the 2004 joint report of the FAO/WHO Workshop on Fruit and Vegetables for Health, the WHO outlined a framework for developing interventions to promote adequate consumption of F&V in Member States( 9 ).

However, in order to develop and assess such interventions, and moreover to monitor the consumption of F&V worldwide, reliable and comparable assessment methods are essential( Reference Agudo 10 , Reference Blanquer, Garcia-Alvarez and Ribas-Barba 11 ). Methodological differences between studies which assess the intake of F&V, including differences in the units of serving size and frequency, and the definition of what constitutes a fruit or vegetable, can often hinder meaningful comparisons( Reference Roark and Niederhauser 12 ). As highlighted by Roark et al. ( Reference Roark and Niederhauser 12 ), the definition of vegetables poses a particular problem. Debate focuses on whether legumes, pulses and/or potatoes are considered to be vegetables( Reference Agudo 10 , Reference Roark and Niederhauser 12 ) and whether fruits should include nuts, olives and fruit juices which are 100 % juice( Reference Agudo 10 ). While F&V can be defined by their nutritional content as ‘low energy-dense foods, relatively high in vitamins, minerals, and other bioactive compounds as well as being a good source of fibre’( Reference Agudo 10 ) (p. 4), there is no agreed understanding of ‘fruit’ or ‘vegetable’ in terms of how they should be captured through dietary assessment methods; that is, what is considered a fruit or vegetable in one country may not be in another. This disparity may create issues when measuring and tracking intake across different regions( Reference Agudo 10 ).

Previous and existing European projects have focused on the standardisation and harmonisation of food classification systems and food composition databases between countries (e.g. the International Food Data Systems Project, the Eurofoods initiative, the Food-Linked Agro-Industrial Research programme, COST Action 99, TRANSFAIR study, EUROFIR, etc.)( Reference Blanquer, Garcia-Alvarez and Ribas-Barba 11 , 13 – Reference Riboli and Kaaks 18 ) and the IDAMES (Innovative Dietary Assessment Methods in Epidemiological Studies and Public Health) project has evaluated new-generation methods to assess dietary intake in Europe( 19 ), developing the European Food Propensity Questionnaire for use within European countries. Guidelines from the European Food Safety Authority recommend the use of a computerised method (e.g. EPIC-SOFT or similar) for collection of accurate, standardised, food consumption data at the European level( 20 , 21 ). However, standards have not, as yet, been developed for the assessment of dietary intake, including intake of F&V, as part of aetiological studies. Thematic Area 1 of the DEDIPAC (DEterminants of DIet and Physical Activity) project( 22 ) aims to address this gap and add to our understanding of the most effective, harmonised methods of dietary intake assessment by preparing a toolkit of the most useful measurement tools of dietary intake that can be used extensively across Europe( 22 , Reference Lakerveld, van der Ploeg and Kroeze 23 ). The aim of the current systematic literature review was to identify suitable assessment methods that may potentially be used to measure intake of F&V in European children and adults in pan-European studies.

Materials and methods

Data sources and study selection

The current review adheres to the guidelines of the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) Statement. The protocol for the review can be accessed from PROSPERO (CRD42014012947)( Reference Harrington, Riordan and Ryan 24 ). A systematic literature search for pan-European studies that assessed the intake of F&V was conducted. For this review, we used the definition of F&V proposed by Agudo( Reference Agudo 10 ): ‘vegetables and foods used as vegetables’, with fruits taken to be fresh or preserved fruits. Our definition included nuts, legumes and potatoes, and only 100 % fruit juice was considered a fruit. Legumes and potatoes are not consistently included as vegetables across dietary assessment methods; therefore, where possible, it was reported whether the instrument in question excluded or included these items as vegetables. Two authors, F.R. and K.R., independently conducted a search of PubMed, EMBASE and Web of Science databases, using combinations of the following search terms: ‘fruit/s’ and ‘vegetable/s’, with keywords for dietary intake, including ‘diet’, ‘eating’, ‘consumption’, ‘intake’, and search terms for European countries. A full copy of the EMBASE search strategy is presented in the online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 1. All searches were limited to English-language literature published from 1990 through to 7 July 2014.

Table 1 Identified instruments according to criteria. Instruments which meet both criteria are shaded

CNSHS, Cross National Student Health Survey; ECRHS, European Community Respiratory Health Survey; EHBS, European Health and Behaviour Survey; ENERGY, EuropeaN Energy balance Research to prevent excessive weight Gain among Youth; EPIC, European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition; ESCAREL, European Study in Non Carious Cervical Lesions; HAPIEE, Health, Alcohol and Psychosocial factors in Eastern Europe; HTT, Health in Times of Transition; IHBS, International Health and Behaviour Survey; LLH, Living Conditions, Lifestyles and Health; MEDIS, MEDiterranean Islands Study; MGSD, Mediterranean Group for the Study of Diabetes; PRIME, Prospective Epidemiological Study of Myocardial Infarction; SENECA, Survey in Europe on Nutrition and the Elderly; a Concerted Action; MONICA, Multinational MONItoring of trends and determinants in CArdiovascular disease; HBSC, Health Behaviour in School-aged Children; HELENA, Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence; TEMPEST, ‘Temptations to Eat Moderated by Personal and Environmental Self-regulatory Tools’; EYHS, European Youth Heart Study; IDEFICS, Identification and prevention of Dietary- and lifestyle-induced health EFfects In Children and infantS; ISAAC, International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood; 24-HDR, 24h recall; PCQ, Primary Caregiver’s Questionnaire; CEHQ, Children’s Eating Habits Questionnaire.

* Based on the IDEFICS instruments which were validated.

† 24-HDR and qualitative 1 d food record method has been validated but not as part of the EYHS.

‡ The reliability study on the FFQ is unpublished.

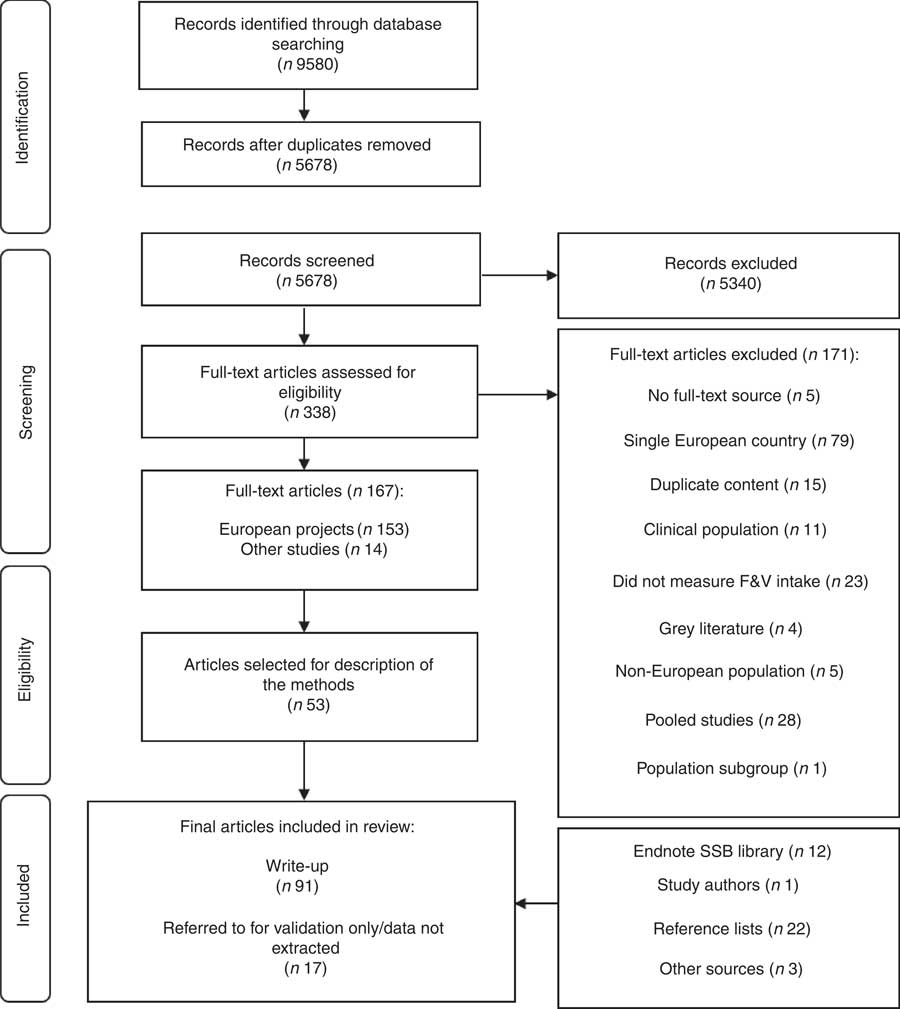

Titles and abstracts of the sourced articles were independently screened by F.R. and K.R. If in doubt regarding inclusion, the article was retained for full-text review. Any disagreement during the full-text review stage was resolved through consultation with a third author, J.M.H. Studies were included if they assessed the intake of F&V within two or more European countries, as defined by the Council of Europe( 25 ). Participants were required to be free-living, healthy populations of any age; therefore we excluded hospital-based populations and studies which focused on a specific disease subgroup (e.g. diabetic cohort) or any fixed societal subgroups (e.g. pregnant women). The review was not limited to certain study designs. If studies compared two groups, one of which was a healthy general population, they were included. Intervention studies were eligible if F&V intake was measured at baseline before any dietary intervention was undertaken. Similarly, case–control studies were included if intake was assessed in population-based controls. Studies were included only if they assessed intake of F&V at the level of the individual; that is, those which assessed household-level consumption of F&V were excluded (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Flow diagram showing study selection process for the current review (F&V, fruit and vegetable; SSB, sugar-sweetened beverages)

Reference lists of all included papers, along with relevant meta-analysis and literature reviews, were reviewed for further publications not identified by the original search. Databases were also searched using the names of individual European projects listed in the DEDIPAC Inventory of Relevant European Studies, a compilation which is an ongoing part of DEDIPAC. Authors were contacted to obtain full versions of the relevant instruments or questionnaires and some articles; and the Endnote library of a concurrently occurring systematic literature review on methods to assess intake of sugar-sweetened beverages was reviewed for further studies.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data extraction was carried out using a form that was developed, piloted and subsequently revised to capture the following data: study design; number and names of European countries involved; sample size (total and number for each country); age range of the included population; the method used and description (including frequency categories for FFQ, number of items/items that referred to F&V, details of portion estimation); mode of administration; and details on the validation or reproducibility. Originally sourced articles which described the assessment methods in the most detail were selected for inclusion in the review, with further information on the methods obtained from articles sourced from reference lists. One reviewer extracted the data for each study, which was confirmed by the other reviewer.

The aim of the current systematic literature review was to identify and describe assessment methods that have been used to assess intake of F&V. Therefore, a comprehensive quality appraisal of each included article was not conducted as part of the current review. However, it was recorded whether or not the instrument in question had been tested for validity and/or reproducibility, and relevant validation studies were referenced where possible. Data were extracted from these studies by P.D., S.E. and N.W.-D. to inform the instrument selection. In order to determine which instruments would be appropriate to use in pan-European studies, two selection criteria were applied: (i) the instrument was reviewed for validity and/or reproducibility, of which a summary of its indicators is presented; and (ii) the instrument was used in more than two countries simultaneously that represented a range of European regions. A ‘range’ meant that at least one country from at least three of the Southern, Northern, Eastern and Western European regions, as defined by the United Nations, were included( 26 ). The results of this selection are shown in Table 1.

Results

Description of the included studies

As shown in Fig. 1, 5678 papers remained once duplicates were removed, and 167 were retained after screening titles and abstracts and following full-text screening. These articles were grouped according to the major European project to which they belonged (n 153) or grouped as ‘Other’ (n 14) if they did not belong to a project. From these 167 articles, fifty-three articles were selected, typically one to three articles per project, which best described the background to the project or the methods used (Fig. 1).

Reviewing the reference lists yielded twenty-two further articles in which the methods were described( Reference Riboli and Kaaks 18 , Reference van Stralen, te Velde and Singh 27 – Reference Maes, Cook and Ottovaere 47 ). Twelve further articles were obtained from the Endnote library on sugar-sweetened beverages in which two additional studies assessing the intake of F&V, the ToyBox study and a study by Kolarzyk et al. ( Reference Kolarzyk, Shpakou and Kleszczewska 48 ), were described. One article was obtained from authors( Reference Hebestreit, Eiben and Reineke 49 ). Unpublished details on the instruments used as part of the I.Family Project( 50 ), the IDEFICS (Identification and prevention of Dietary- and lifestyle-induced health EFfects In Children and infantS) study follow-up, were obtained through contact with the IDEFICS group. Articles on the background and validation of the Food4Me project, published after the search dates, were also added to the review( Reference Celis-Morales, Livingstone and Marsaux 51 – Reference Fallaize, Forster and Macready 53 ) . The term ‘study’ is used in the current review to refer to the larger project, rather than individual analyses/publications that may arise from the same project, and therefore use the same methodology.

Taking together the articles sourced and selected from our original search (n 53), from reference lists (n 22), from the concurrent review on sugar-sweetened beverages (n 12), from authors (n 1) and articles added subsequently (n 3), a total of ninety-one articles covering fifty-one studies were included in the review. For each of the methods identified, article(s) which described the validation or reliability testing performed for that method were recorded. As a result, seventeen further articles were sourced in which validation and/or reliability testing for the identified methods was described. The characteristics of the included studies( Reference Walda, Tabak and Smit 4 , Reference Riboli and Kaaks 18 , Reference van Stralen, te Velde and Singh 27 – Reference Kolarzyk, Shpakou and Kleszczewska 48 , 50 – Reference Lanfer, Hebestreit and Ahrens 145 ) are described in Table 2.

Table 2 Summary of the included studies: design, population studied, dietary assessment instruments used and details of validation and/or reproducibility. Studies selected according to the two criteria are shaded. Where validation or reliability data was not available for fruit and vegetables specifically, this is highlighted in bold font

CNSHS, Cross National Student Health Survey; ECRHS, European Community Respiratory Health Survey; EHBS, European Health and Behaviour Survey; ENERGY, EuropeaN Energy balance Research to prevent excessive weight Gain among Youth; EPIC, European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition; ESCAREL, European Study in Non Carious Cervical Lesions; HAPIEE, Health, Alcohol and Psychosocial factors in Eastern Europe; HTT, Health in Times of Transition; IHBS, International Health and Behaviour Survey; LLH, Living Conditions, Lifestyles and Health; MEDIS, MEDiterranean Islands Study; MGSD, Mediterranean Group for the Study of Diabetes; SENECA, Survey in Europe on Nutrition and the Elderly; a Concerted Action; MONICA, Multinational MONItoring of trends and determinants in CArdiovascular disease; HBSC, Health Behaviour in School-aged Children; HELENA, Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence; TEMPEST, ‘Temptations to Eat Moderated by Personal and Environmental Self-regulatory Tools’; EYHS, European Youth Heart Study; IDEFICS, Identification and prevention of Dietary- and lifestyle-induced health EFfects In Children and infantS; ISAAC, International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood; NR, not reported; 24-HDR, 24 h recall; PCQ, Primary Caregiver’s Questionnaire; F&V, fruit and vegetables; YANA-C, Young Adolescents’ Nutrition Assessment on Computer; CEHQ, Children’s Eating Habits Questionnaire.

* Funded by the Wellcome Trust programme grant entitled ‘Determinants of Cardiovascular Diseases in Eastern Europe: A multi-centre cohort study’ (reference number 064947/Z/01/Z) and developed by Martin Bobak, Anne Peasey, Hynek Pikhart (UCL), Ruzena Kubinova, Lubomíra Milla Novosibirsk, Sofia Malyutina, Oksana Bragina (Prague), Andrzej Pajak, Aleksandra Gilis-Januszewska (Krakow).

† Original instrument obtained for review.

‡ Validation or reproducibility of the instrument was not reported in the article and no reference to validation or reproducibility studies were provided.

From the sourced articles, fifty-one pan-European studies in total were identified: thirty-five named projects and sixteen smaller projects( Reference Kolarzyk, Shpakou and Kleszczewska 48 , Reference Baldini, Pasqui and Bordoni 54 , Reference Behanova, Nagyova and Katreniakova 56 , Reference Esteve, Riboli and Pequignot 65 , Reference Galanti, Hansson and Bergstrom 69 , Reference Hupkens, Knibbe and Drop 72 , Reference O’Neill, Carroll and Corridan 82 , Reference Parfitt, Rubba and Bolton 83 , Reference Rylander, Axelsson and Megevand 88 , Reference Terry, Howe and Pogoda 93 , Reference Tessier and Gerber 94 , Reference Van Diepen, Scholten and Korobili 107 , Reference Gerrits, O’Hara and Piko 109 , Reference Larsson, Klock and Astrom 113 , Reference Szczepanska, Deka and Calyniuk 114 , Reference Antova, Pattenden and Nikiforov 116 ). Most studies assessed dietary intake of F&V among adults( Reference Riboli and Kaaks 18 , 41 , Reference de Groot and van Staveren 44 , Reference Haveman-Nies, Bokje and Ocke 46 , Reference Kolarzyk, Shpakou and Kleszczewska 48 , 50 , Reference Celis-Morales, Livingstone and Marsaux 51 , Reference Baldini, Pasqui and Bordoni 54 – Reference El Ansari, Stock and Mikolajczyk 57 , Reference Hooper, Heinrich and Omenaas 59 , Reference Steptoe and Wardle 60 , Reference Bartlett, Lussi and West 64 – Reference Prattala, Paalanen and Grinberga 66 , Reference de Morais, Oliveira and Afonso 68 , Reference Galanti, Hansson and Bergstrom 69 , Reference Abe, Stickley and Roberts 71 , Reference Hupkens, Knibbe and Drop 72 , Reference Grant, Wardle and Steptoe 75 – Reference Karamanos, Thanopoulou and Angelico 79 , Reference Galvin, Kiely and Harrington 81 – Reference Dauchet, Ferrieres and Arveiler 84 , Reference Klepp, Perez-Rodrigo and De Bourdeaudhuij 86 , Reference Rylander, Axelsson and Megevand 88 , Reference Tabak, Feskens and Heederik 92 – Reference Tessier and Gerber 94 , Reference Van Diepen, Scholten and Korobili 107 , Reference Paalanen, Prattala and Palosuo 146 , Reference Boylan, Lallukka and Lahelma 147 ). Five assessed parents or caregivers( Reference van Stralen, te Velde and Singh 27 , 50 , Reference Lehto, Ray and Te Velde 85 – Reference Yngve, Wolf and Poortvliet 87 , Reference Manios 102 ). Four studies examined intake among older adults, namely MEDIS (MEDiterranean Islands Study)( Reference Tyrovolas, Psaltopoulou and Pounis 78 ), the Seven Countries Study( Reference Walda, Tabak and Smit 4 , Reference Virtanen, Feskens and Rasanen 91 , Reference Tabak, Feskens and Heederik 92 ), SENECA (Survey in Europe on Nutrition and the Elderly; a Concerted Action)( Reference de Groot, Hautvast and van Staveren 43 , Reference Schroll, Moreiras-Varela and Schlettwein-Gsell 90 , Reference de Groot, Verheijden and de Henauw 148 , Reference van Staveren, de Groot and Burema 149 ) and the ‘Food in later life’ study( Reference de Morais, Oliveira and Afonso 68 ). Nine studies assessed intake among children( Reference van Stralen, te Velde and Singh 27 , Reference Riddoch, Edwards and Page 30 , Reference Ahrens, Bammann and Siani 37 , 50 , Reference Lehto, Ray and Te Velde 85 , Reference Klepp, Perez-Rodrigo and De Bourdeaudhuij 86 , Reference Manios, Androutsos and Katsarou 101 , Reference Antova, Pattenden and Nikiforov 116 , Reference Nagel, Weinmayr and Kleiner 120 ) in age ranges 2–9 years( Reference Ahrens, Bammann and Siani 37 , Reference Pala, Lissner and Hebestreit 118 , Reference Bornhorst, Huybrechts and Hebestreit 119 ), 3–6 years( Reference Androutsos, Apostolidou and Iotova 95 – Reference Pil, Putman and Cardon 106 ), 2–11 years( 50 ), 7–11 years( Reference Antova, Pattenden and Nikiforov 116 ), 11 years( Reference Lehto, Ray and Te Velde 85 ) and 10–12 years( Reference van Stralen, te Velde and Singh 27 ), and seven assessed intake among adolescents( Reference Moreno, De Henauw and Gonzalez-Gross 32 , 50 , Reference Gerrits, O’Hara and Piko 109 , Reference Zaborskis, Moceviciene and Iannotti 110 , Reference Larsson, Klock and Astrom 113 – Reference Stok, de Vet and de Wit 115 ).

Validation

Table 2 provides detail on the instruments’ validation. Of the studies which were validated or tested for reproducibility and fulfilled inclusion criterion 1 (Table 1), validity and reliability of the FFQ was assessed using biomarkers( Reference Crispim, Geelen and Souverein 63 , Reference Brunner, Stallone and Juneja 126 ), FFQ( Reference Forster, Fallaize and Gallagher 52 ), food records( Reference Haraldsdottir, Thorsdottir and de Almeida 42 , Reference Fallaize, Forster and Macready 53 , Reference Petkeviciene, Simila and Becker 80 , Reference Goldbohm, van den Brandt and Brants 128 – Reference Vereecken and Maes 132 , Reference Huybrechts, De Backer and De Bacquer 137 , Reference Tyrovolas, Pounis and Bountziouka 138 ) or 24 h recalls (24-HDR)( Reference Vereecken, De Bourdeaudhuij and Maes 36 , Reference Bel-Serrat, Mouratidou and Pala 38 , Reference Petkeviciene, Simila and Becker 80 , Reference Brinkman, Kellen and Zeegers 129 , Reference Bel-Serrat, Fernandez Alvira and Pala 135 ) as the reference method. In fifteen studies, validity was assessed by crude correlations( Reference Vereecken, Covents and Sichert-Hellert 35 , Reference Vereecken, De Bourdeaudhuij and Maes 36 , Reference Bel-Serrat, Mouratidou and Pala 38 , Reference Haraldsdottir, Thorsdottir and de Almeida 42 , Reference Fallaize, Forster and Macready 53 , Reference Crispim, Geelen and Souverein 63 , Reference Petkeviciene, Simila and Becker 80 , Reference Brunner, Stallone and Juneja 126 , Reference Goldbohm, van den Brandt and Brants 128 , Reference Kristjansdottir, Andersen and Haraldsdottir 130 , Reference Vereecken and Maes 132 , Reference Huybrechts, De Backer and De Bacquer 137 , Reference Tyrovolas, Pounis and Bountziouka 138 ), energy-adjusted correlations( Reference Forster, Fallaize and Gallagher 52 , Reference Fallaize, Forster and Macready 53 , Reference Brunner, Stallone and Juneja 126 , Reference Brinkman, Kellen and Zeegers 129 ), de-attenuated correlation coefficients( Reference Vereecken, De Bourdeaudhuij and Maes 36 , Reference Bel-Serrat, Mouratidou and Pala 38 , Reference Brinkman, Kellen and Zeegers 129 , Reference Huybrechts, De Backer and De Bacquer 137 ), mean or median differences in F&V consumption( Reference Vereecken, Covents and Sichert-Hellert 35 , Reference Vereecken, De Bourdeaudhuij and Maes 36 , Reference Bel-Serrat, Mouratidou and Pala 38 , Reference Haraldsdottir, Thorsdottir and de Almeida 42 , Reference Forster, Fallaize and Gallagher 52 , Reference Fallaize, Forster and Macready 53 , Reference Petkeviciene, Simila and Becker 80 , Reference Brunner, Stallone and Juneja 126 , Reference Goldbohm, van den Brandt and Brants 128 – Reference Kristjansdottir, Andersen and Haraldsdottir 130 , Reference Vereecken and Maes 132 , Reference Huybrechts, De Backer and De Bacquer 137 , Reference Tyrovolas, Pounis and Bountziouka 138 ), exact level of agreement of F&V consumption( Reference Bel-Serrat, Mouratidou and Pala 38 , Reference Haraldsdottir, Thorsdottir and de Almeida 42 , Reference Forster, Fallaize and Gallagher 52 , Reference Fallaize, Forster and Macready 53 , Reference Petkeviciene, Simila and Becker 80 , Reference Brunner, Stallone and Juneja 126 , Reference Kristjansdottir, Andersen and Haraldsdottir 130 , Reference Vereecken and Maes 132 , Reference Huybrechts, De Backer and De Bacquer 137 , Reference Tyrovolas, Pounis and Bountziouka 138 ), Bland–Altman plots( Reference Vereecken, De Bourdeaudhuij and Maes 36 , Reference Forster, Fallaize and Gallagher 52 , Reference Fallaize, Forster and Macready 53 , Reference Brinkman, Kellen and Zeegers 129 ) or weighted kappa( Reference Bel-Serrat, Mouratidou and Pala 38 , Reference Huybrechts, De Backer and De Bacquer 137 ) between the FFQ and reference instrument. In nine studies, reliability of F&V consumption was assessed by correlations( Reference Vereecken, De Bourdeaudhuij and Maes 36 , Reference Haraldsdottir, Thorsdottir and de Almeida 42 , Reference Fallaize, Forster and Macready 53 , Reference Petkeviciene, Simila and Becker 80 , Reference Bloemberg, Kromhout and Obermann-De Boer 131 , Reference Vereecken and Maes 132 , Reference Huybrechts, De Backer and De Bacquer 137 , Reference Lanfer, Hebestreit and Ahrens 145 ), mean/median differences( Reference Vereecken, De Bourdeaudhuij and Maes 36 , Reference Petkeviciene, Simila and Becker 80 , Reference Huybrechts, De Backer and De Bacquer 137 , Reference Tyrovolas, Pounis and Bountziouka 138 , Reference Lanfer, Hebestreit and Ahrens 145 ), weighted kappa( Reference Vereecken and Maes 132 , Reference Tyrovolas, Pounis and Bountziouka 138 , Reference Lanfer, Hebestreit and Ahrens 145 ) or intraclass correlation coefficients( Reference Huybrechts, De Backer and De Bacquer 137 ) between subsequent assessments of the FFQ. Where available, data were extracted and are provided in detail in the online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 2.

Dietary intake assessment methods

Types of methods

Several methods were used to assess dietary intake of F&V in the identified studies. The vast majority of the pan-European studies used FFQ (n 42)( Reference van Stralen, te Velde and Singh 27 , Reference Riboli, Hunt and Slimani 29 , Reference Riddoch, Edwards and Page 30 , Reference Vereecken, De Bourdeaudhuij and Maes 36 , 41 , Reference Kolarzyk, Shpakou and Kleszczewska 48 , 50 , Reference Forster, Fallaize and Gallagher 52 , Reference Baldini, Pasqui and Bordoni 54 – Reference Behanova, Nagyova and Katreniakova 56 , Reference Mikolajczyk, El Ansari and Maxwell 58 – Reference Steptoe and Wardle 60 , Reference Bartlett, Lussi and West 64 – Reference Prattala, Paalanen and Grinberga 66 , Reference Galanti, Hansson and Bergstrom 69 , Reference Abe, Stickley and Roberts 71 , Reference Hupkens, Knibbe and Drop 72 , Reference Grant, Wardle and Steptoe 75 , Reference Pounis, de Lorgeril and Salen 76 , Reference Tyrovolas, Psaltopoulou and Pounis 78 , Reference Karamanos, Thanopoulou and Angelico 79 , Reference O’Neill, Carroll and Corridan 82 , Reference Dauchet, Ferrieres and Arveiler 84 – Reference Klepp, Perez-Rodrigo and De Bourdeaudhuij 86 , Reference Rylander, Axelsson and Megevand 88 , Reference Terry, Howe and Pogoda 93 , Reference Mouratidou, Miguel and Androutsos 104 , Reference Gerrits, O’Hara and Piko 109 , Reference Zaborskis, Moceviciene and Iannotti 110 , Reference Larsson, Klock and Astrom 113 – Reference Antova, Pattenden and Nikiforov 116 , Reference Nagel, Weinmayr and Kleiner 120 , Reference Bel-Serrat, Mouratidou and Bornhorst 139 , Reference Paalanen, Prattala and Palosuo 146 , Reference Peasey, Bobak and Kubinova 150 ). Since a common FFQ instrument was not used across all countries in the EPIC (European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition) study, only the EPIC-SOFT instrument is discussed in the current review.

According to the two selection criteria (i.e. whether tested for validity or reproducibility and used in more than two countries representing a range of European regions; Table 1), six instruments were appropriate to assess intake of F&V in future pan-European studies among adults: EPIC-SOFT, the Food4Me FFQ, the ToyBox Primary Caregiver’s Questionnaire, the ENERGY (EuropeaN Energy balance Research to prevent excessive weight Gain among Youth) parent questionnaire, and the dietary history methods used by the SENECA study and Seven Countries Study. Three instruments used to assess intake among adolescents, HELENA-DIAT (Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence–Dietary Assessment Tool), HELENA online FFQ and the HBSC (Health Behaviour in School-aged Children) FFQ, fulfilled the criteria. The ENERGY children’s questionnaire and the instruments used by the IDEFICS, Pro-Children and ToyBox studies appeared appropriate to measure F&V among children. Although not validated separately, the I.Family instruments were based closely on those of the IDEFICS study and also met the criteria. The 24-HDR preceded by the 1 d qualitative food record used in the EYHS (European Youth Heart Study) was a validated method but not tested in the study population( Reference Lytle, Nichaman and Obarzanek 144 ). While Table 1 indicates the selected methods, in the interest of comprehensiveness, details on all the identified methods are provided.

Instruments which met the two selection criteria for which validation data on F&V intake were available are summarized in Table 3. Of those for use among adults, F&V intakes assessed by EPIC-SOFT were described by authors as having weak to moderate correlation with biomarkers( Reference Crispim, Geelen and Souverein 63 ). The Food4Me FFQ was reported to demonstrate moderate agreement with a 4 d weighed food record( Reference Fallaize, Forster and Macready 53 ) and good agreement with the EPIC-Norfolk FFQ( Reference Forster, Fallaize and Gallagher 52 ). While the ToyBox Primary Caregiver’s Questionnaire was tested for reliability there were no data available for F&V. Similarly, the ENERGY parent questionnaire was tested for reliability but data were unpublished. The Seven Countries Study dietary history instrument was not validated but reproducible( Reference Bloemberg, Kromhout and Obermann-De Boer 131 ). HELENA-DIAT, administered by self-report, was reported to have good agreement with intakes when administered by interview( Reference Vereecken, Covents and Sichert-Hellert 35 ). The HELENA-FFQ was found to have adequate reliability( Reference Vereecken, De Bourdeaudhuij and Maes 36 ). The HBSC FFQ was found to be reproducible and reported to have good agreement with a 7 d food diary( Reference Vereecken and Maes 132 ).

Table 3 Summary of the selected instruments which were validated (n 8) for assessment of fruit and vegetables

EPIC, European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition; 24-HDR, 24 h recall; HBSC, Health Behaviour in School-aged Children; HELENA, Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence; IDEFICS, Identification and prevention of Dietary- and lifestyle-induced health EFfects In Children and infants; CEHQ, Children’s Eating Habits Questionnaire; self-admin., self-administered.

* Original instrument obtained for review.

The IDEFICS FFQ was compared with two 24-HDR but had low agreement with 24-HDR according to the authors, and agreement varied by food group and age of child in a population across eight survey sites( Reference Bel-Serrat, Mouratidou and Pala 38 ). However, the instrument had good agreement with 24-HDR in a sample of Spanish children( Reference Bel-Serrat, Fernandez Alvira and Pala 135 ) and has been demonstrated to be reproducible( Reference Lanfer, Hebestreit and Ahrens 145 ). The Pro-Children instrument, when compared with 7 d( Reference Kristjansdottir, Andersen and Haraldsdottir 130 ) and 1 d( Reference Haraldsdottir, Thorsdottir and de Almeida 42 ) diet records, was reported to have moderate to good validity for ranking individuals according to usual intake and was reproducible( Reference Haraldsdottir, Thorsdottir and de Almeida 42 ). The ToyBox study instrument was shown to be reproducible and was reported to have moderate relative validity when compared with 3 d diet records( Reference Huybrechts, De Backer and De Bacquer 137 ).

FFQ

Range of items and definitions

Characteristics of the identified FFQ are summarised in Table 4. FFQ were used to assess dietary intake, identify determinants of dietary intake, or test diet–disease associations and identify disease risk factors. The number of food items listed on these FFQ ranged between sixty-six and 322, with the number of items relating to fruit and vegetables ranging from one item( Reference van Stralen, te Velde and Singh 27 , Reference Steptoe and Wardle 60 ) to ninety-five items( Reference O’Neill, Carroll and Corridan 82 ). Several FFQ used non-itemised terms such as ‘fruit’, ‘vegetables’, ‘fresh fruit’, ‘raw vegetables’ and ‘cooked vegetables’( Reference Ahrens, Bammann and Siani 37 , Reference Haraldsdottir, Thorsdottir and de Almeida 42 , Reference Kolarzyk, Shpakou and Kleszczewska 48 , Reference Behanova, Nagyova and Katreniakova 56 , Reference Mikolajczyk, El Ansari and Maxwell 58 , Reference Bartlett, Lussi and West 64 , Reference Prattala, Paalanen and Grinberga 66 , Reference Paalanen, Prattala and Alfthan 67 , Reference Galanti, Hansson and Bergstrom 69 , Reference Grant, Wardle and Steptoe 75 , Reference Dauchet, Ferrieres and Arveiler 84 , Reference Gonzalez-Gil, Mouratidou and Cardon 100 , Reference Gerrits, O’Hara and Piko 109 , Reference Zaborskis, Moceviciene and Iannotti 110 , Reference Szczepanska, Deka and Calyniuk 114 – Reference Antova, Pattenden and Nikiforov 116 , Reference Nagel, Weinmayr and Kleiner 120 ), while others listed individual fruits and vegetables( Reference Riddoch, Edwards and Page 30 , Reference van Dongen, Lentjes and Wijckmans 39 , 41 , Reference Forster, Fallaize and Gallagher 52 , Reference Fallaize, Forster and Macready 53 , Reference O’Neill, Carroll and Corridan 82 , Reference Peasey, Bobak and Kubinova 150 ). FFQ could be classed as having low (<5 items relating to fruit or vegetables) or high (>5 items relating to fruit or vegetables) comprehensiveness based on the cut-off used by Cook et al. ( Reference Cook, O’Reilly and Derosa 151 ). Thirteen FFQ were classed as having low comprehensiveness for F&V, including the ENERGY and HBSC questionnaires( Reference van Stralen, te Velde and Singh 27 , Reference Currie, Griebler and Inchley 31 , Reference Kolarzyk, Shpakou and Kleszczewska 48 , Reference Behanova, Nagyova and Katreniakova 56 , Reference El Ansari, Stock and Mikolajczyk 57 , Reference Bartlett, Lussi and West 64 , Reference Prattala, Paalanen and Grinberga 66 , Reference Abe, Stickley and Roberts 71 , Reference Grant, Wardle and Steptoe 75 , Reference Szczepanska, Deka and Calyniuk 114 – Reference Antova, Pattenden and Nikiforov 116 , Reference Nagel, Weinmayr and Kleiner 120 ).

Table 4 Summary of FFQ: instrument purpose and characteristics

CNSHS, Cross National Student Health Survey; ENERGY, EuropeaN Energy balance Research to prevent excessive weight Gain among Youth; EHBS, European Health and Behaviour Survey; ESCAREL, European Study in Non Carious Cervical Lesions; HAPIEE, Health, Alcohol and Psychosocial factors in Eastern Europe; HTT, Health in Times of Transition; IHBS, International Health and Behaviour Survey; LLH, Living Conditions, Lifestyles and Health; MGSD, Mediterranean Group for the Study of Diabetes; PRIME, Prospective Epidemiological Study of Myocardial Infarction; MEDIS, MEDiterranean Islands Study; HELENA, Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence; TEMPEST, ‘Temptations to Eat Moderated by Personal and Environmental Self-regulatory Tools’; HBSC, Health Behaviour in School-aged Children; IDEFICS, Identification and prevention of Dietary- and lifestyle-induced health EFfects In Children and infantS; ISAAC, International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood; EPIC, European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition; NR, not reported; EBRB, energy balance-related behaviours; F&V, fruit and vegetables; veg, vegetables; self-admin., self-administered; CATI, computer-assisted telephone interview; PAPI, paper-assisted personal interview.

* Original instrument obtained for review.

† Original instrument not obtained.

‡ Information on Food4Me instrument was obtained from study authors.

Some FFQ further subdivided F&V into ‘raw/fresh’, ‘cooked’ or ‘tinned’, each with separate items listed underneath( Reference Peasey, Bobak and Kubinova 150 ). The NORBAGREEN FFQ( 41 ) and the FFQ used by Larsson et al.( Reference Larsson, Klock and Astrom 113 ) assessed the consumption of individual fruits and vegetables, but also included a cross-check question on the total consumption of vegetables and fruits. The NORBAGREEN FFQ assessed consumption within different contexts and using different cooking styles; for example, asking participants to report the frequency of consumption of ‘cooked, canned or steamed vegetables’ and of ‘dried fruit or berries’.

Where individual F&V items were listed, FFQ also varied in terms of whether pulses( Reference Bel-Serrat, Mouratidou and Pala 38 , Reference O’Neill, Carroll and Corridan 82 ) or potatoes( Reference Mikolajczyk, El Ansari and Maxwell 58 , Reference Gerrits, O’Hara and Piko 109 ) were included under ‘vegetables’. Some FFQ listed potatoes as ‘cooked vegetables’( Reference Bel-Serrat, Mouratidou and Pala 38 , Reference Paalanen, Prattala and Alfthan 67 ), ‘white-yellowish vegetables’( Reference O’Neill, Carroll and Corridan 82 ) or specified ‘vegetables (potatoes excluded)’( Reference Abe, Stickley and Roberts 71 , Reference Larsson, Klock and Astrom 113 ). Many FFQ listed separate potato items or ‘potatoes’ and ‘legumes/pulses’ as separate group headings with their own items listed below( Reference Riddoch, Edwards and Page 30 , Reference Vereecken, De Bourdeaudhuij and Maes 36 , Reference Bel-Serrat, Mouratidou and Pala 38 , Reference van Dongen, Lentjes and Wijckmans 39 , Reference Kolarzyk, Shpakou and Kleszczewska 48 , Reference Forster, Fallaize and Gallagher 52 , Reference Fallaize, Forster and Macready 53 , Reference Prattala, Paalanen and Grinberga 66 , Reference Gonzalez-Gil, Mouratidou and Cardon 100 , Reference Larsson, Klock and Astrom 113 , Reference Peasey, Bobak and Kubinova 150 ). With some exceptions( Reference Forster, Fallaize and Gallagher 52 , Reference Fallaize, Forster and Macready 53 , Reference Klepp, Perez-Rodrigo and De Bourdeaudhuij 86 , Reference Mouratidou, Miguel and Androutsos 104 ), if an FFQ listed fruit or vegetable juice it did not always specify 100 % fruit or vegetable juice( Reference van Stralen, te Velde and Singh 27 , Reference Klepp, Perez-Rodrigo and De Bourdeaudhuij 86 , Reference Gonzalez-Gil, Mouratidou and Cardon 100 ). Therefore, participants could interpret this as including fruit squash and dilutions.

Mode and structure

All FFQ were paper-based and self-administered with some exceptions in which the FFQ was web-based( Reference Celis-Morales, Livingstone and Marsaux 51 ), administered via face-to-face interview( Reference Terry, Howe and Pogoda 93 , Reference Boylan, Lallukka and Lahelma 147 ) or by computer-assisted telephone interview( 41 ). Most of the identified FFQ used pre-coded frequency categories. The majority provided a single frequency scale with typically five or six categories extending from ‘never’, ‘less than once a month’ or ‘less than once a week’ to ‘every day’, ‘more than once a day’, ‘more than X times per day’ or ’several times a day’( Reference Currie, Griebler and Inchley 31 , Reference Weiland, Bjorksten and Brunekreef 40 , Reference Kolarzyk, Shpakou and Kleszczewska 48 , Reference Mouratidou, Miguel and Androutsos 104 , Reference Larsson, Klock and Astrom 113 , Reference Szczepanska, Deka and Calyniuk 114 , Reference Bel-Serrat, Mouratidou and Santaliestra-Pasias 122 ), although the ENERGY FFQ asked participants to select from seven frequency options per week or six frequency options per day. The ESCAREL (European Study in Non Carious Cervical Lesions) FFQ provided a two-step frequency scale: participants first specified whether they consumed fruit juice ‘often’ and then provided a frequency from ‘more than three times per week’ to ‘less than once per week’.

Time period

Most FFQ specified the time period to which consumption frequency referred, generally the previous 12 months. However, other time periods were used, including the previous 3–4 months( Reference O’Neill, Carroll and Corridan 82 ), 3 months( Reference Boylan, Welch and Pikhart 70 ), 1 month( Reference Kolarzyk, Shpakou and Kleszczewska 48 , Reference Forster, Fallaize and Gallagher 52 – Reference Baldini, Pasqui and Bordoni 54 ) and 1 week( Reference van Stralen, te Velde and Singh 27 , Reference Prattala, Paalanen and Grinberga 66 , Reference Abe, Stickley and Roberts 71 , Reference Zaborskis, Moceviciene and Iannotti 110 , Reference Bel-Serrat, Mouratidou and Bornhorst 139 ), or consumption on an average day( Reference Stok, de Vet and de Wit 115 ). The remaining FFQ did not provide a specific time period and participants were directed to report usual or habitual intake. Some FFQ assessed consumption of certain F&V by season( Reference Esteve, Riboli and Pequignot 65 , Reference Antova, Pattenden and Nikiforov 116 ).

Portion size estimation

The majority of FFQ were semi-quantitative and assessed both frequency and amount; in most cases, assessing portion size using photographs( Reference Riddoch, Edwards and Page 30 , Reference Vereecken, De Bourdeaudhuij and Maes 36 , Reference van Dongen, Lentjes and Wijckmans 39 , 50 , Reference Forster, Fallaize and Gallagher 52 , Reference Fallaize, Forster and Macready 53 , Reference Terry, Howe and Pogoda 93 , Reference Androutsos, Apostolidou and Iotova 95 – Reference Duvinage, Ibrügger and Kreichauf 99 , Reference Manios, Androutsos and Katsarou 101 , Reference Manios 102 , Reference Mouratidou, Miguel and Androutsos 104 – Reference Pil, Putman and Cardon 106 ), absolute weights( Reference van Dongen, Lentjes and Wijckmans 39 ) or household measures( Reference Vereecken, De Bourdeaudhuij and Maes 36 , Reference van Dongen, Lentjes and Wijckmans 39 , Reference Karamanos, Thanopoulou and Angelico 79 ). Fruit was often estimated in natural units or standard portions (e.g. one piece, one fruit( Reference O’Neill, Carroll and Corridan 82 )). Other FFQ asked participants to record the quantity eaten for each food item either in tablespoons for vegetables (unless otherwise indicated as florets, slices, etc.) or by small, medium and large for fruit( Reference O’Neill, Carroll and Corridan 82 ). The ToyBox Children’s FFQ asked participants to select from a pre-coded list of portion size ranges for each separate food item, providing examples of typical food items corresponding to these measurements (e.g. 1 tablespoon of prepared vegetables =30 g). The ENERGY questionnaire asked participants to report the number of glasses or small bottles, cans and/or bottles, and specified volumes for each.

Some FFQ recorded portion size in-line; that is, participants were asked to report the frequency of a named portion( Reference Baldini, Pasqui and Bordoni 54 , Reference Behanova, Nagyova and Katreniakova 56 , Reference Galanti, Hansson and Bergstrom 69 , Reference Karamanos, Thanopoulou and Angelico 79 , Reference Dauchet, Ferrieres and Arveiler 84 , Reference Gonzalez-Gil, Mouratidou and Cardon 100 , Reference Gerrits, O’Hara and Piko 109 , Reference Stok, de Vet and de Wit 115 ). The Willett FFQ used by Baldini et al. ( Reference Baldini, Pasqui and Bordoni 54 ) provided a detailed description of what constitutes a usual serving size for each of the 120 FFQ items and the MGSD (Mediterranean Group for the Study of Diabetes) FFQ( Reference Karamanos, Thanopoulou and Angelico 79 ) outlined the usual serving size for different food categories (i.e. one serving of raw vegetables constitutes 100 g or about 1 cup).

Diet records/diet diaries

The characteristics of the identified diet records are summarised in Table 5. Diet records were typically used to determine and compare estimates of dietary intake across regions.

Table 5 Summary of diet records: instrument purpose and characteristics

SENECA, Survey in Europe on Nutrition and the Elderly; a Concerted Action; MONICA, Multinational MONItoring of trends and determinants in CArdiovascular disease; F&V, fruit and vegetables; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; 24-HDR, 24 h recall; self-admin., self-administered, vit., vitamin; IUNA, Irish Universities Nutrition Alliance.

* Original instrument obtained for review.

Seven pan-European studies( Reference de Groot and van Staveren 44 , Reference Haveman-Nies, Bokje and Ocke 46 , Reference de Morais, Oliveira and Afonso 68 , Reference Galvin, Kiely and Harrington 81 , Reference Parfitt, Rubba and Bolton 83 , Reference Tabak, Feskens and Heederik 92 , Reference Tessier and Gerber 94 ) used diet records or diaries, either a 7 d record or three consecutive day records. With the exception of studies which used weighed records( Reference Parfitt, Rubba and Bolton 83 ) or a mixed approach( Reference Galvin, Kiely and Harrington 81 ), most studies estimated portion size using photographs( Reference Riddoch, Edwards and Page 30 , Reference Haveman-Nies, Bokje and Ocke 46 , Reference Virtanen, Feskens and Rasanen 91 ), household measures and objects (e.g. cups, spoons, etc.)( Reference Riddoch, Edwards and Page 30 , Reference de Groot and van Staveren 44 , Reference Haveman-Nies, Bokje and Ocke 46 ), standard units( Reference Haveman-Nies, Bokje and Ocke 46 ) or an artificial model of foods( Reference Haveman-Nies, Bokje and Ocke 46 , Reference Virtanen, Feskens and Rasanen 91 ). Participants were typically asked to record a description of the food eaten, the time and location at which it was eaten, an estimated portion, the preparation method, brand names (or, if possible, recipe details), and weights or amounts of leftovers( Reference Parfitt, Rubba and Bolton 83 ). A few records were pre-coded or structured( Reference Haveman-Nies, Bokje and Ocke 46 , Reference Evans, Ruidavets and McCrum 108 ).

Dietary history method

The other method identified (Table 5) was the cross-check dietary history method used as part of the Seven Countries Study. Food consumption recorded at each meal occasion was used to generate a list of foods. This list was then used to assess consumption of each food on a daily, weekly or monthly basis. Tessier et al. ( Reference Tessier and Gerber 94 ) used a qualitative diet history method to record present diet in comparison with past diet. This was largely open-ended but included a frequency scale for vegetable consumption.

Dietary recalls

Characteristics of the identified 24-HDR are summarised in Table 6. The majority of the 24-HDR were used to determine estimates of dietary intake, comparing estimates across regions or over time. Among the nine studies which used the 24-HDR method( Reference Slimani, Deharveng and Charrondiere 28 , Reference Riddoch, Edwards and Page 30 , Reference Vereecken, Covents and Sichert-Hellert 35 , Reference Bel-Serrat, Mouratidou and Pala 38 , Reference Pomerleau, McKee and Robertson 55 , 74 , Reference Elwing, Kullberg and Kucinskiene 77 , Reference Klepp, Perez-Rodrigo and De Bourdeaudhuij 86 , Reference Van Diepen, Scholten and Korobili 107 ), five were computerised methods. Two were conducted via face-to-face interview (i.e. SACINA and EPIC) and three were self-administered (i.e. HELENA, SACANA child and SACANA adult 24-HDR). There were six paper-based methods. Both the IDEFICS and I.Family 24-HDR programs, SACINA( Reference Bel-Serrat, Mouratidou and Pala 38 ) and SACANA( 50 ), and the program used by the HELENA study, HELENA-DIAT( Reference Vereecken, Covents and Sichert-Hellert 35 ), were based on the YANA-C (Young Adolescents’ Nutrition Assessment on Computer) and structured by six meals/times throughout the day. Information was entered directly into the program, with the exception of the Hungary centre where participants completed the 24-HDR at home, after which the data were entered. EPIC-SOFT differed in that before foods were entered per meal, a ‘quick list’ of all food and recipes consumed during that day was entered by an interviewer in chronological order, with each quick list item described and quantified.

Table 6 Summary of dietary recalls: instrument purpose and characteristics

EPIC, European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition; HELENA, Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence; EYHS, European Youth Heart Study; 24-HDR, 24 h recall; IDEFICS, Identification and prevention of Dietary- and lifestyle-induced health EFfects In Children and infantS; NR, not reported; F&V, fruit and vegetables; self-admin., self-administered.

* Original instrument obtained for review.

All four computer-based 24-HDR incorporated prompts and reminders, including probes and warnings for data exceeding normal ranges; checked entries for occurrence of fruit, vegetables and sweets; or probed for food items often eaten in combination with other items( Reference Vereecken, Covents and Matthys 34 , Reference Vereecken, Covents and Sichert-Hellert 35 ) or displayed checklists containing foods easily forgotten( Reference Slimani, Deharveng and Charrondiere 28 ). The remaining 24-HDR were conducted via face-to-face interview and incorporated different levels of structure, pre-coding and prompts, including listing some items so that participants were specifically prompted to think about their consumption of different fruits, vegetables and juices( Reference Androutsos, Katsarou and Payr 96 , Reference Bloemberg, Kromhout and Obermann-De Boer 131 ). Portion size was assessed largely using photographs( Reference Slimani, Deharveng and Charrondiere 28 , Reference Vereecken, Covents and Sichert-Hellert 35 , Reference Bel-Serrat, Mouratidou and Pala 38 , Reference Pomerleau, McKee and Robertson 55 , Reference Yngve, Wolf and Poortvliet 87 ), household measures( Reference Pomerleau, McKee and Robertson 55 , Reference Elwing, Kullberg and Kucinskiene 77 ), drawings of commonly used foods( Reference Pomerleau, McKee and Robertson 55 ) or standard measures (i.e. cups).

Discussion

The aim of the current review was to identify the main methods used to assess intake of F&V in pan-European studies that measured dietary intake of F&V (FFQ, n 42; 24-HDR, n 11; diet record/diet diary/dietary history, n 7). Of the identified methods, forty-one were used to assess intake among adults, five of which assessed intake among parents/caregivers. Nine assessed intake among children ranging in age from 2 to 12 years, and seven were used among adolescents. Key differences were found to exist between methods to measure intake of F&V, which should be considered in terms of how they might affect the comprehensiveness, and the comparability, of the intake data collected. For example, the identified FFQ differed in many respects, some of which have been reported previously( Reference Cade, Thompson and Burley 152 , Reference Thompson and Subar 153 ). These included: (i) listing individual fruits or vegetables v. non-itemised, broad terms; (ii) including potatoes and legumes under the heading of vegetables; (iii) variation in the number and range of items (from about twenty to forty specific items to fewer than five broad items); (iv) variation in the number and range of frequency categories; and (v) variation in the method of portion size estimation.

While dietary assessment methods used in US( Reference Serra-Majem, Frost Andersen and Henrique-Sanchez 156 ) or UK( Reference Shim, Oh and Kim 157 ) studies have previously been compiled, the current review is the first to specifically focus on systematically identifying and describing instruments that can be used to assess intake of F&V in pan-European studies. As European-wide interventions to promote the consumption of F&V are further developed, valid instruments that can assess and monitor intake in a standardised and comparable way across Europe are essential. In order to identify instruments which would be most promising to use in future pan-European studies to measure F&V, and those to include in the DEDIPAC toolbox, two selection criteria were applied: (i) the instrument was tested for validity and/or reproducibility; and (ii) the instrument was used in more than two countries simultaneously which represented a range of European regions.

According to these criteria, six instruments appear to be suitable to assess intake of F&V among adults in pan-European studies. However, only two of the studies had been validated for F&V intake (EPIC-SOFT and Food4Me), using biomarkers and 4 d diet records, respectively. All three instruments selected to assess intake among adolescents, the HELENA-DIAT instrument, the HELENA online FFQ and the HBSC FFQ, had been validated, using 24-HDR (HELENA instruments) and both 24-HDR and 7 d diet record (HBSC) as reference methods, with good agreement but some overestimation of intakes by the HELENA and HBSC FFQ. Five instruments were selected to assess intake among children; however, just three instruments were validated for F&V intake (IDEFICS FFQ, Pro-Children and ToyBox), using 24-HDR (IDEFICS), 7 d (Pro-Children) and 3d (ToyBox) diet records as the reference method, demonstrating moderately good ranking for food groups by the Pro-Children instrument, moderate relative validity for ToyBox and low agreement of the IDEFICS FFQ with 24-HDR.

As already stated, the results of the current review will feed into the development of the DEDIPAC toolbox of dietary intake assessment methods, which will provide a basis for appraising and selecting suitable instruments for use in future pan-European studies. However, before selecting from the eight validated instruments shortlisted herein, the quality of the validity and/or reproducibility studies performed for the instrument should be considered to assess the suitability of the instruments identified for the study in question; for example, judging the reference method used (i.e. biomarkers, long-term or short-term dietary assessment method) and the statistics used to assess validity (i.e. whether compared at group level, mean/median differences, or assessed using crude, energy-adjusted, de-attenuated or intraclass correlations)( Reference Serra-Majem, Frost Andersen and Henrique-Sanchez 156 ). Although a tool may have been tested for validity in several countries, ideally it should be validated in the population in which it is to be used. Although no selection was made based on the comprehensiveness of the instrument, this may be another criterion to consider before utilising the instrument in question; that is, based on the cut-off of five items used by Cook et al.( Reference Cook, O’Reilly and Derosa 151 ), the ENERGY parent and child instruments, the ToyBox parent’s questionnaire and the HBSC FFQ were ranked as having low comprehensiveness for F&V.

The purpose of the dietary assessment should also be taken into consideration. Most of the identified FFQ were used to identify determinants of dietary intake or examine diet–disease associations. This contrasts with 24-HDR and diet records, which were primarily used to assess intake for cross-cultural comparisons or over time. It is generally accepted( Reference Thompson and Subar 153 ) that diet records, 24-HDR and dietary history methods, unlike FFQ, are suitable for cross-cultural comparisons. FFQ are typically designed to be population-specific, encapsulating local dietary customs and foods, and may not be the ideal instrument to use across several countries( Reference Thompson and Subar 153 ). However, this also must be balanced against the feasibility of using the instrument; namely, resource-demanding methods such as interview-administered 24-HDR (EPIC-SOFT) compared with self-completed 24-HDR (HELENA-DIAT) or FFQ (Food4Me, IDEFICS, HBSC, HELENA, Pro-Children and ToyBox instruments), which needs to be taken into consideration to determine whether an instrument can be used effectively to assess intake of F&V in a chosen pan-European population.

Owing to the lack of an appraisal tool to rate dietary assessment instruments on the basis of their characteristics, the quality of the identified instruments was not assessed as part of the current review. Future work should consider developing a standardised approach to appraisal which would greatly aid any comparison of quality across dietary assessment tools, particularly where validation studies are absent. Comparing the characteristics of the instruments identified in the current review could provide a basis for agreement on such quality standards; for example, requiring instruments to assess portion size and, where they do, that a consistent approach be used – defining servings in units which are understandable to participants (e.g. ‘15 g or tablespoon’ of cooked vegetables, ‘beaker=225 ml’ of fruit juice) or through use of a standardised photographic food atlas.

It may also be possible to decide how specific FFQ questions, including the format of these questions, could be better standardised across FFQ used in pan-European studies, even if the FFQ themselves are country-specific. As highlighted, the identified FFQ varied considerably on comprehensiveness (number of items) and detail (use of broad terms like ‘fruit’ or ‘vegetables’ v. specific items). While cut-offs such as that used by Cook et al. ( Reference Cook, O’Reilly and Derosa 151 ) may be applied, any judgement on comprehensiveness must be balanced against the purpose of the assessment; for example, is the aim is to examine dietary patterns overall, rather than focus specifically on health and disease associations with individual fruits and vegetables, and is there additional benefit to be gained from providing an exhaustive list? However, where broad terms are included, this needs to be supplemented with adequate explanation or an inventory of items intended to fall under these terms, to avoid the possibility of participant misunderstanding and consequently variation across countries and regions. For example, some FFQ listed fruit or vegetable juice but did not always specify 100 % fruit or vegetable juice. Similarly, some did not clarify whether potatoes or legumes were covered by a broader term such as ‘vegetables’.

The current review has a number of strengths and limits. A comprehensive search strategy was used that aimed to identify all pan-European studies measuring the intake of F&V among children and adults, and their associated assessment instruments. The search was supplemented by hand-searching reference lists, sourcing further instruments through contact with study authors, and reviewing the results of concurrently occurring systematic literature reviews. Where possible, a copy of the original instrument was obtained to facilitate the description of the methods. However, although a comprehensive search was conducted, the possibility that all relevant articles were not identified cannot be excluded. The review is limited in its focus to pan-European studies, as the aim was to identify instruments used in European populations and to provide a selection of methods which may be applied to future studies based in these countries. However, this does not preclude the fact that additional instruments and innovative methods( Reference Shim, Oh and Kim 157 ) that have been used and validated as part of large-scale non-European studies, such as the US NHANES (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey)( 158 ), may be suitable for assessing intakes across Europe. In some cases, a copy of the original instrument or article that detailed characteristics of the assessment method could not be identified and the description provided may be limited as a result. This being said, the primary aim of the review was to identify assessment instruments. Therefore the results serve as a valuable reference. As mentioned, no quality appraisal of the identified instruments could be conducted. However, by indicating which instruments were validated and/or tested for reproducibility, summarising these results and applying additional criteria, the review has selected a number of potential instruments and provided a basis for determining the suitability of instruments for use in future studies.

Conclusion

The present review has identified a range of instruments to assess intake of F&V and indicates that a large degree of variability exists between currently available instruments. To standardise the measurement of F&V intake between European countries, instruments should use a consistent approach to assessing F&V; for example, using itemised terms and, when non-itemised broad terms are used, clarifying whether potatoes and legumes/pulses are captured by these terms. The current review has indicated eight instruments validated for F&V intake that may be suitable to assess the intake of F&V among adult, child or adolescent populations. These methods have been used in pan-European populations, encompassing a range of European regions, and should be considered for use by future studies focused on evaluating consumption of F&V.

Acknowledgements

Financial support: The preparation of this paper was supported by the DEDIPAC Knowledge Hub. This work was supported by the Joint Programming Initiative ‘Healthy Diet for a Healthy Life’. The funding agency supporting this work was The Health Research Board (HRB), Ireland (DEDIPAC/2013/1). Conflict of interest: L.F.A. was co-author on the Pro-Children validity and reproducibility study. Authorship: F.R. planned and conducted the review, and drafted and revised the paper. K.R. planned and conducted the review, and drafted the paper. I.J.P. drafted and revised the paper. M.B.S. contributed to the planning, and drafted and revised the paper. L.F.A. contributed to the planning, and drafted and revised the paper. A.G. drafted and revised the paper. P.v.V. drafted and revised the paper. S.E. conducted the review of validation data, and drafted and revised the paper. P.D. conducted the review of validation data, and drafted and revised the paper. N.W.-D. conducted the review of validation data, and drafted and revised the paper. J.M.H. contributed to the planning, and drafted and revised the paper. Ethics of human subject participation: Not applicable.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1368980016002366