Pakistan is one of the worst performers in child mortality in the world, with an under-5 mortality rate of 81 per 1000 live births in 2015( 1 ). Widespread malnutrition is reported in over 50 % of children living in Pakistan( Reference Agha, Maqbool and Anwar 2 ). Both over- and undernutrition are prevalent within Pakistani families, with coexisting nutrition-related diseases; while 45 % of children have stunted growth, 40 % of Pakistani school-aged children are overweight( Reference Corvalan, Dangour and Uauy 3 – Reference Netuveli, Hurwitz and Levy 7 ). Good feeding practices in early childhood should be a key area of focus to prevent malnutrition and measures to improve complementary feeding (CF) have been recommended for future investment( Reference Rodgers, Paxton and Massey 8 – Reference Das, Achakzai and Bhutta 10 ).

The WHO defines CF as: ‘The process starting when breast milk alone is no longer sufficient to meet the nutritional requirements of infants, and therefore other foods and liquids are needed, along with breast milk’( 11 ). CF therefore focuses on bridging the gradual transition between 6 and 24 months from exclusive breast-feeding to solid foods eaten by the whole family alongside breast-feeding. An appropriate diet following WHO guidelines in the first 2 years with breast-feeding and CF can decrease all-cause childhood mortality by approximately 20 % in low-income countries( Reference Jones, Steketee and Black 9 ). It can also guarantee sufficient nutritional intake, reducing obesogenic dietary behaviours while ensuring healthy gain of weight in children( Reference Rodgers, Paxton and Massey 8 ).

The 2010 WHO Infant and Young Child Feeding (IYCF) guidelines, an internationally ratified framework adopted in Pakistan, emphasize as a global public health recommendation that infants should be exclusively breast-fed for the first 6 months of life. Thereafter, infants should receive safe and nutritionally adequate complementary foods while breast-feeding continues for up to 2 years of age or beyond( 12 ). The period from 6 months to 24 months of age is a critical and vulnerable period of infant growth( Reference Liaqat, Rizvi and Qayyum 13 ).

Current literature shows that knowledge of infant feeding practices and CF is lacking among Pakistani families, with Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) data from Pakistan highlighting inadequate breast-feeding and complementary feeding practices (CFP)( Reference Hanif 14 , Reference Hazir, Senarath and Agho 15 ). The Pakistan DHS has only recently begun collecting information on all IYCF indicators, so an examination of these factors is particularly important( Reference Senarath, Agho and Akram 16 , 17 ).

The present systematic review is part of a large project exploring the adequacy of CFP based on IYCF recommended minimum dietary diversity and meal frequency, timing of introducing CF, and barriers and promoters influencing CFP among South Asians (SA). SA communities have fundamental differences in geography and religion, which both influence feeding practices. As such, the current review is one of four looking at CFP in Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, and SA living in high-income countries. The work aims to inform future projects to develop and evaluate culturally appropriate interventions to improve CFP across SA families in these different communities.

Methods

The present review (PROSPERO registration number CRD42014014025) summarizes publications on CFP in SA families in Pakistan only, with concurrent reviews summarizing publications on CFP in SA families in India( Reference Manikam, Robinson and Kuah 18 ), Bangladesh( Reference Manikam, Prasad and Dharmaratnam 19 ) and high-income countries (L Manikam, R Lingam, I Lever et al., unpublished results), respectively.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were included if they met the following criteria.

-

∙ Participants: children aged 0–2 years, parents, carers and/or their families.

-

∙ Outcomes: adequacy of CF (based on minimum dietary diversity and meal frequency), timing of introduction of CF and barriers/promoters to incorporating WHO recommended CFP.

-

∙ Language: studies published in English, or with translation available.

-

∙ Year: published from 2000 or later.

In the IYCF indicators, introduction of CF is assessed as the proportion of infants aged 6–8 months who receive solid, semi-solid or soft foods( 20 ). In contrast, minimum dietary diversity (MDD) is assessed by the proportion of infants 6–23 months of age who receive foods from four or more food groups. The seven WHO IYCF recommended food groups are( 20 ):

-

1. grains, roots and tubers;

-

2. legumes and nuts;

-

3. dairy products (e.g. milk, yoghurt, cheese);

-

4. flesh foods (e.g. meat, fish, poultry and liver/organ meats);

-

5. eggs;

-

6. vitamin A-rich fruits and vegetables; and

-

7. other fruits and vegetables.

While the consumption of Fe-rich or Fe-fortified foods is commonly assessed as a separate IYCF indicator, this was incorporated within dietary diversity for ease of interpretation in the current review.

Finally, minimum meal frequency (MMF) is assessed by the proportion of breast-fed and non-breast-fed children 6–23 months of age who receive solid, semi-solid or soft foods (also including milk feeds for non-breast-fed children) the minimum number of times or more per day: two times for 6–8 months, three times for 9–23 months and four times for 6–23 months (if not breast-fed)( 20 ).

All study types (qualitative/quantitative/mixed) were included to ensure the diversity of evidence was captured and summarized, to be of relevance to both policy makers and health and social care professionals. We excluded studies focusing solely on exclusive breast-feeding and interventional studies.

Information sources

We searched the following databases: MEDLINE, EMBASE, Global Health, BanglaJOL, CINAHL, Web of Science, OVID Maternity & Infant Care, The Cochrane Library, POPLINE and WHO Global Health Library. Searches were conducted in December 2014 and updated in June 2016.

Members of electronic networks on @jiscmail.ac.uk including minority-ethnic-health and networks (e.g. South Asian Health Foundation) developed from the Specialist Electronic Library for Ethnicity and Health were contacted to request any additional or unpublished material from members of the networks. Bibliographies of included articles were also hand-searched for additional publications.

Search strategy

The search strategy included terms for ‘feeding’, ‘South Asian’ (including terms specifying all major subgroups as below) and ‘children’. For example, the search strings used for MEDLINE were the following.

Term 1: children <2 years

Infant OR Baby OR Babies OR Toddler OR Newborn OR Neonate* OR Child OR Preschool OR Nursery school OR Kid OR Paediatric* OR Minors OR Boy OR Girl

Term 2: feeding

Nutritional Physiological Phenomena OR Food OR Feeding behaviour OR Feed OR Nutrition OR Wean OR fortify* OR Milk

Term 3: Asians

Ethnic* OR India* OR Pakistan* OR Bangladesh* OR Sri Lanka OR Islam OR Hinduism OR Muslim OR Indian subcontinent OR South Asia

Study selection and data extraction

In total, 45 712 titles and abstracts were screened against inclusion criteria. Two reviewers assessed these papers independently and conflicts were resolved by discussion with the team. In view of the large number of articles deemed eligible for full-text review, articles published before the year 2000 were excluded. In total, 44 852 titles and abstracts were excluded.

This left 860 articles describing CFP in SA children for full-text review by two independent reviewers. One hundred and thirty-one full-text articles were ultimately extracted, of which seventeen were sufficiently relevant to Pakistan.

Data were extracted by a single reviewer using a piloted modified worksheet including: country of study; study type; study year; study objectives; population studied, eligibility criteria and illness diagnosis; study design; ethical approval; sampling; data collection and analysis; feeding behaviours; adequacy of CFP; timing of initiation of CF; bias; value of the research; and weight of evidence. A second member of the research team checked each extraction.

Result synthesis

The eligible studies tended to address broad research questions, were conducted using qualitative and/or quantitative and/or descriptive methods, and were not presented following standardized reporting guidelines (i.e. STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) for observational studies or COREQ (Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research) for qualitative research). Meta-analyses were therefore not undertaken.

To standardize study classifications, the formal definitions below were applied.

-

1. Interventional study: a study in which patients are assigned to a treatment group or a comparison group and followed prospectively.

-

2. Cohort study: an observational study in which a group of patients are followed over time. These may be prospective or retrospective.

-

3. Cross-sectional study: an observational study that examines the relationship between health-related characteristics and other variables of interest in a defined population at one particular time.

-

4. Case–control study: a study that compares patients who have a disease or outcome of interest (cases) with patients who do not have the disease or outcome of interest (controls).

-

5. Qualitative: a study which aims to explore the experiences or opinions of families through interviews, focus groups, reflective field notes and other non-quantitative approaches.

-

6. Mixed methods: a study that combines both quantitative and qualitative methodology.

In view of the studies’ heterogeneity regarding methodology, participants, interventions and outcomes, a narrative approach to synthesis was utilized using guidance developed from the University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) and the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC)( 21 – Reference Popay, Roberts and Sowden 24 ).

The evidence reviewed is presented as a narrative report, with the results categorized following IYCF indicators on: (i) adequacy of CFP, comprising dietary diversity, consumption of Fe-rich foods, meal frequency, timing of introduction of CFP, food hygiene and sources of advice for feeding; and (ii) barriers/promoters influencing CFP.

Barriers were defined as obstacles or impediments to achieving correct CFP, while promoters were defined as supporters to achieving correct CFP. These were sub-categorized into factors influencing at the family level (e.g. family members) and the organizational level (e.g. health-care providers, hospitals, political bodies).

Quality assurance

The CRD guidance emphasizes the importance of using a structured approach to quality assessment when assessing descriptive or qualitative studies for inclusion in reviews. However, it acknowledges the lack of consensus on the definition of poor quality with some arguing that using rigid quality criteria leads to the unnecessary exclusion of papers( 21 ).

In our review, the EPPI-Centre Weight of Evidence Framework was used to allow for objective judgements about the value of each study in answering the review question( Reference Gough 25 ). It examines three study aspects: quality of methodology, relevance of methodology and relevance of evidence to the review question, and categorizes them into ‘low’ (L), ‘medium’ (M) or ‘high’ (H). The overall weight of evidence (WOE), i.e. the overall assessment of the extent to which the study provides evidence to answer the review question, is also rated as L, M or H. Two independent reviewers performed this evaluation, with additional arbitration by other team members where required. One study with an overall WOE=L is included in the table summarizing included studies but is not discussed further within the ‘Results’ or ‘Discussion’ section below.

Results

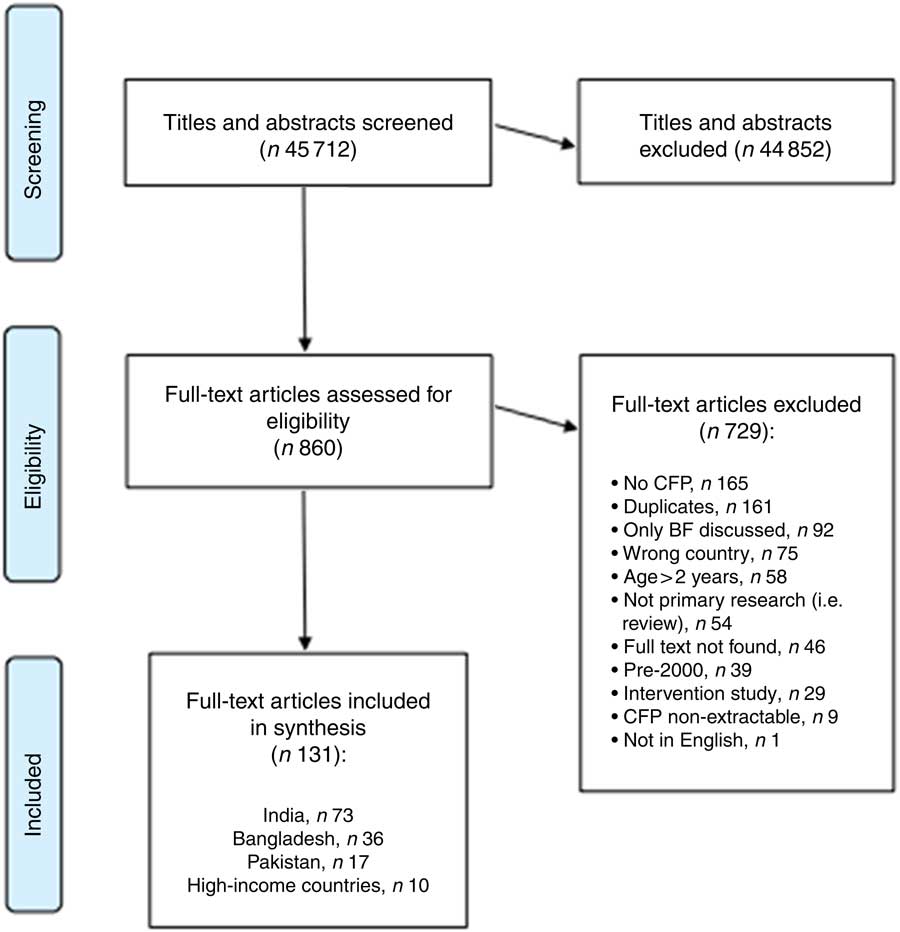

Of the 45 712 studies identified, seventeen studies focusing on CFP in Pakistan were ultimately included in the current systematic review. The study selection process is denoted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 Study selection process for the current systematic review (CFP, complementary feeding practices; BF, breast-feeding)

Study and participant characteristics

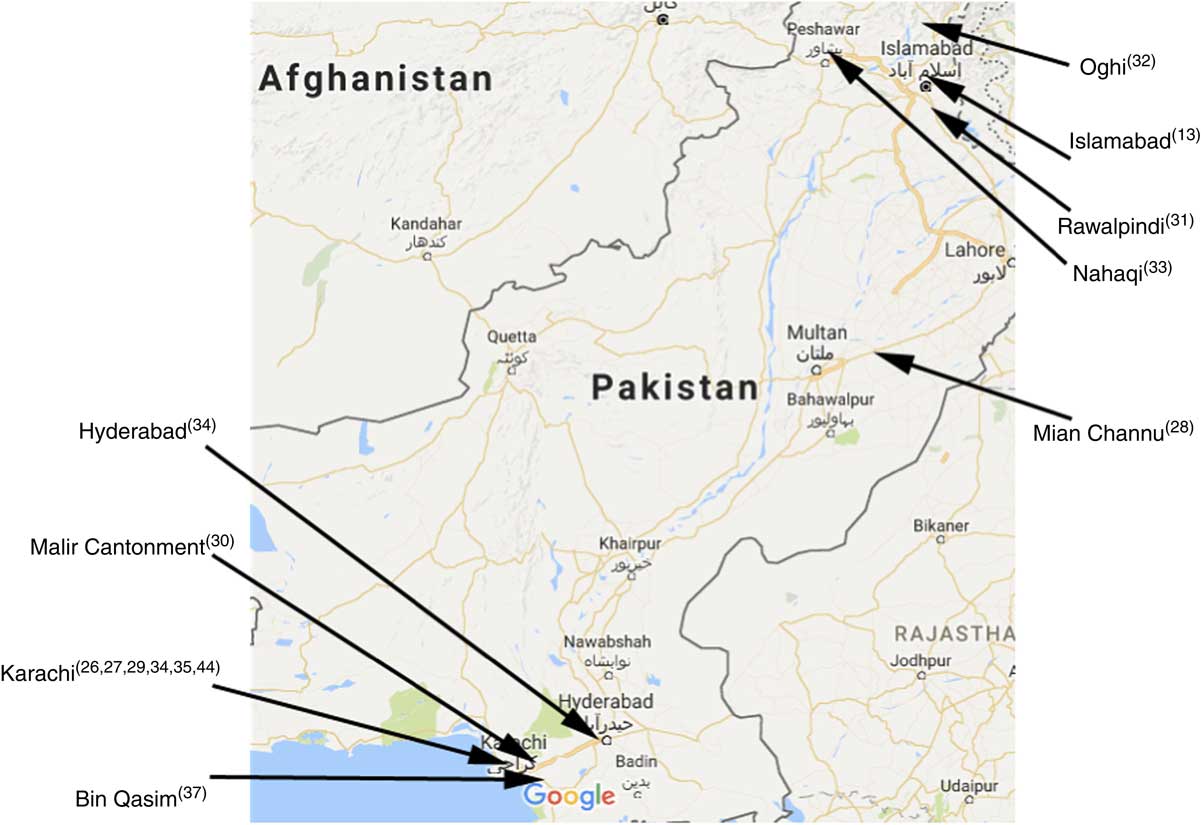

These seventeen studies consisted of fourteen cross-sectional studies, two qualitative studies and one cohort study. Table 1 summarizes all included studies. Figure 2 illustrates the study locations of fourteen of these seventeen included studies, with the remaining three not detailing precise study locations.

Fig. 2 (colour online) Location map of fourteen of the studies included the current systematic review (map courtesy of Google Maps; data © 2017 Google)

Table 1 Summary of studies included in the current systematic review

CF, complementary feeding/complementary food; NGO, non-governmental organization.

Table 2 presents the weight of evidence awarded to each of the studies. The core narrative themes extracted from the papers are presented under the following headings: (i) adequacy of CFP and (ii) factors associated with CFP.

Table 2 Weight of evidence awarded to each study in the current systematic review

L, low; M, medium; H, high.

Adequacy of complementary feeding practices

As per the WHO IYCF indicators, adequacy of CFP is assessed according to dietary diversity, meal frequency and timing of introducing CFP. These are detailed in the subsections below, with three further subsections discussing Fe-rich foods, food hygiene and advice providers.

Dietary diversity

Dietary diversity was explored in nine studies, with food consumption recall being the commonest way to assess MDD. Most studies did not provide precise rates of the population being fed with each food group, and no study properly assessed rates of achieved MDD across four of the seven WHO IYCF food groups defined above.

Table 3 denotes a summary of all complementary food groups identified from the studies. Of the nine studies with data relevant to MDD, five studies described CFP involving four of the seven food groups( Reference Krebs, Mazariegos and Tshefu 26 – Reference Shamim, Naz and Waseem Jamalvi 30 ). Overall, Pakistani CF diets were described as being based largely on grains and legumes by Lingam et al. (WOE=H)( Reference Lingam, Gupta and Zafar 31 ). Shamim et al. (WOE=M) observed frequent poor dietary diversity, with even those who were fed recommended weaning items (including home-made cereals, egg, banana and fish) having a high prevalence of stunting (31·4 %), wasting (20·3 %) and underweight (46·4 %)( Reference Shamim, Naz and Waseem Jamalvi 30 ).

Table 3 Foods utilized for complementary feeding in Pakistan, categorized into WHO food groups

If type of fruit/vegetable was not provided, it was classified as ‘other fruits and vegetables’.

In nine studies, the ‘grains, roots and tubers’ food group was utilized for CFP. Eight named ‘other fruits and vegetables’, six mentioned ‘legumes and nuts’, five studies included ‘dairy products’, four studies ‘flesh foods’ and four studies ‘eggs’. No studies mentioned ‘vitamin A-rich fruits and vegetables’.

‘Grains, roots and tubers’ were most commonly mentioned as being used for CF, included in nine studies. Sarwar (WOE=H) observed that 42 % of sampled children aged 3–12 months were first introduced to CF with cereal, and 49 % with rice; at the time of the study, 84 % were fed rice and 29 % cereal( Reference Sarwar 28 ). In comparison, Ahmed et al. (WOE=M) found that 10 % were introduced to CF with cereal, and 20 % currently were fed rice( Reference Ahmed, Farooq and Jadoon 32 ). Mehkari et al. (WOE=H) listed common CF food items including daliya (porridge, 64 %), several made with rice such as kitchri (rice and pulses, 69 %) and kheer (rice with milk, 48 %), and mashed potato (65 %)( Reference Mehkari, Zehra and Yasin 27 ). Shamim (WOE=M) also listed kitchri, daliya/dayla and suji (a wheat derivative) as CF foods( Reference Shamim 29 ). Lingam et al. (WOE=H) observed that Cerelac, a store-bought porridge, was common among affluent families, and in some families, it was mixed with boiled potatoes( Reference Lingam, Gupta and Zafar 31 ).

‘Other fruits and vegetables’ were mentioned in eight studies with none directly specifying use of ‘vitamin A-rich fruits and vegetables’. Sarwar (WOE=H) observed that 11 % of infants aged 3–12 months were first introduced to CF with fruits and 11 % with vegetables, and 60 % were currently fed fruits and 47 % vegetables( Reference Sarwar 28 ); while Ahmed et al. (WOE=M) noted that 30 % were first weaned with fruits of any sort, while 30 % were currently fed apples and 30 % bananas( Reference Ahmed, Farooq and Jadoon 32 ). Banana was popular, with Shamim (WOE=M) finding that banana was the only fruit offered by participants, and that seasonal fresh fruit and vegetables were not offered at all( Reference Shamim 29 ). Shamim et al. (WOE=M) and Dykes et al. (WOE=M) also observed the use of banana( Reference Shamim, Naz and Waseem Jamalvi 30 , Reference Dykes, Lhussier and Bangash 33 ).

‘Legumes and nuts’ were identified in six studies for CF, primarily through the use of pulses in kitchri, a dish made of pulses with rice. Dev et al. (WOE=H) found that 93·0 % of home-made food given by sampled mothers in Bhains Colony in Karachi contained kitchri, as did 42·6 % of home-made food given in Bilal Colony( Reference Dev, Shaikh and Shaikh 34 ); and Mehkari et al. (WOE=H) found that 69·1 % of participants used kitchri for CF( Reference Mehkari, Zehra and Yasin 27 ). Shamim et al. (WOE=M), Shamim (WOE=M) and Lingam et al. (WOE=H) also listed kitchri as a weaning food( Reference Shamim 29 – Reference Lingam, Gupta and Zafar 31 ). Krebs et al. (WOE=M) described the use of beans and lentils, and groundnuts (peanuts)( Reference Krebs, Mazariegos and Tshefu 26 ).

In terms of ‘dairy products’, Sarwar (WOE=H) described the use of cow’s milk by 37 % of those sampled and Ahmed et al. (WOE=M) described its use by 10 %( Reference Sarwar 28 , Reference Ahmed, Farooq and Jadoon 32 ). Shamim (WOE=M) described extensive use of milk-based cereals( Reference Shamim 29 ). Sarwar also found that 20 % of infants were introduced to CF with eggs, and 44 % were currently fed eggs( Reference Mehkari, Zehra and Yasin 27 ), although conversely Shamim (WOE=M) claimed egg seldom comprises CF foods( Reference Shamim 29 ).

The use of commercial foods was mentioned by six studies, with usage rates ranging from 11 to 52 %. Shamim (WOE=M) found that 52 % of mothers used commercial cereals for CF( Reference Shamim 29 ), while Mohsin et al. (WOE=H) reported that 46·4 % used commercial food items in general( Reference Mohsin, Shaikh and Shaikh 35 ), and in Mehkari et al. (WOE=H) this proportion was 15 %( Reference Mehkari, Zehra and Yasin 27 ). Sarwar (WOE=H) claimed that 2 % of infants were introduced to CF with sweet convenience foods, and at the time of the study 11 % were regularly consuming savoury convenience foods and 20 % sweet convenience foods( Reference Sarwar 28 ). Dev et al. (WOE=H) reported that 21 % of mothers in Bilal Colony provided only shop-bought/processed CF compared with 37 % in Bhains Colony, attributing this difference to the presence of a non-governmental organization in Bilal( Reference Dev, Shaikh and Shaikh 34 ). Shamim et al. (WOE=M) also mentioned the use of commercial foods( Reference Shamim, Naz and Waseem Jamalvi 30 ). Sarwar and Mohsin et al. reported tea was used for CF, which is not part of any WHO recommended food group( Reference Sarwar 28 , Reference Mohsin, Shaikh and Shaikh 35 ).

Iron-rich foods

There was little information on consumption of Fe-rich foods. Use of flesh foods (meat, fish, poultry and liver/organ meats) was mentioned in only four studies. In Sarwar (WOE=H), 2 % of infants were first introduced to CF with meat, and at the time of the study 24 % were fed with meat( Reference Sarwar 28 ). This is a similar proportion to Krebs et al. (WOE=M), who found that 22·2 % were fed meat regularly( Reference Gough 25 ). Conversely, Shamim (WOE=M) claimed that meat was almost never used for CF( Reference Shamim 29 ). Otherwise, Shamim et al. (WOE=M) described fish as being given for CF ‘regularly’ in fishing villages, although it is considered too costly elsewhere( Reference Shamim, Naz and Waseem Jamalvi 30 ).

Meal frequency

Meal frequency was measured in four studies, with rates of MMF ranging from 35·7 to 55·8 % across the studies. MMF is two times for 6–8 months, three times for 9–23 months and four times for 6–23 months (if not breast-fed)( Reference Hanif 14 ).

Mohsin et al. (WOE=H) found that 55·8 % of infants aged 0–2 years were fed solid foods three times daily, achieving MMF if paired with breast-feeding; they also found that 39·9 % were fed twice daily (which would meet MMF only for 6–8-month-olds) and 2·2 % were fed only once daily( Reference Mohsin, Shaikh and Shaikh 35 ). Memon et al. (WOE=H) found 50 % of infants aged 12–23 months received complementary foods at the MMF optimal rate of three or four times daily( Reference Memon, Shaikh and Kousar 36 ). Krebs et al. (WOE=M) found that 37·7 % of infants aged 5–9 months were fed three or more times daily, meaning at least this proportion at a minimum met MMF, and 50·7 % were fed once or twice daily( Reference Gough 25 ). Comparing two colonies in Karachi, Dev et al. (WOE=H) found that 48·3 % were fed three or more times daily in Bilal Colony, but 35·7 % in Bhains Colony; as many as 10·2 and 9·5 % in the respective colonies were fed only once daily( Reference Dev, Shaikh and Shaikh 34 ).

Timing of introducing complementary feeding

Table 4 denotes a summary of timing of when CF was introduced across the studies. The most commonly listed age for CF commencement was at 3–6 months (eleven studies), followed by 6–9 months of age, the optimal period (nine studies). The third most common were under 3 months of age and 9–12 months of age, both by three studies. One study described CF introduction between 1 and 2 years.

Table 4 Timing of introduction of complementary feeding in Pakistan

Based on the 2006–07 Pakistan DHS, Senarath et al. (WOE=H) noted that timely initiation of CF in Pakistan was the lowest (39 %) compared with other SA countries: India achieved 55 %, Nepal 70 %, Bangladesh 71 % and Sri Lanka 84 %( Reference Senarath, Agho and Akram 16 ). There was little improvement in the timing of introducing CF in infants aged 6–9 months between 1990–91 (32·1 %) and 2006–07 (36·3 %) in the national DHS, and the timing of introducing CF was ranked as ‘poor’ by Hanif (WOE=M)( Reference Hanif 14 ); Hazir et al. (WOE=H) found 60·8 % of Pakistani infants aged 6–8 months had not commenced CF, with 10·6 % of infants starting CF earlier than the recommended time( Reference Hazir, Senarath and Agho 15 ).

Hazir et al. (WOE=H) found that urban respondents were more likely to practise early or timely CF, with 13·8 % giving CF at 3–5 months and at 56·6 % at 6–8 months( Reference Hazir, Senarath and Agho 15 ). Only 9·1 % of rural respondents gave CF at 3–5 months and only 33·2 % at 6–8 months( Reference Hazir, Senarath and Agho 15 ). Liaqat et al. (WOE=M) observed CF starting as late as up to 12 months among 64 % of uneducated respondents, compared with 17 % of educated respondents( Reference Liaqat, Rizvi and Qayyum 13 ), and Shamim (WOE=M) found that less educated mothers sometimes delayed CF until the infant was 1 year old( Reference Shamim 29 ). Dev et al. (WOE=H) described CF beginning between 1 and 2 years for 15·3 % in Bilal Colony and for 18·4 % in Bhains Colony( Reference Dev, Shaikh and Shaikh 34 ).

Food hygiene

Two studies looked at hand-washing and found good compliance; Mohsin et al. (WOE=H) found that 92 % of respondents washed hands before cooking( Reference Mohsin, Shaikh and Shaikh 35 ), which is similar to Mehkari et al. (WOE=H) where 98 % practised hand-washing before feeding children( Reference Mehkari, Zehra and Yasin 27 ). However, Mohsin et al. also found that 71·7 % did not boil drinking-water( Reference Dev, Shaikh and Shaikh 34 ).

Meal preparation for infants was generally done together with other family cooking. Three studies described meal preparation, with Mohsin et al. (WOE=H) noting that 50 % of the mothers were cooking complementary foods separately from adult foods and Memon et al. (WOE=H) describing that only 33 % of children aged 6–11 months were provided with meals especially prepared for them( Reference Mohsin, Shaikh and Shaikh 35 , Reference Memon, Shaikh and Kousar 36 ). Only 25·6 % of mothers who home-cooked food prepared meals especially for the infant in Shamim (WOE=M)( Reference Shamim 29 ).

Advice providers

Nine studies discussed advice providers. Of these, eight studies highlighted the importance of advice from family and friends, and one indicated that advice from medical professionals predominated. Memon et al. (WOE=H) found that 78 % of mothers in their sample were advised primarily by family members, compared with 22 % by medical professionals( Reference Memon, Shaikh and Kousar 36 ), and Sarwar (WOE=H) found that two-thirds of mothers received advice from family and friends on weaning( Reference Sarwar 28 ). Six other studies similarly emphasized the importance of families and friends in giving advice for CF( Reference Liaqat, Rizvi and Qayyum 13 , Reference Shamim 29 , Reference Ahmed, Farooq and Jadoon 32 – Reference Dev, Shaikh and Shaikh 34 , Reference Premji, Khowaja and Meherali 37 ). Mohsin et al. (WOE=H) was the one study that indicated otherwise, saying that doctors were the primary source of knowledge in the case of commercial complementary foods for 52·9 %, compared with 25·4 % who consulted relatives and friends( Reference Mohsin, Shaikh and Shaikh 35 ). Three studies mentioned the media as another source( Reference Shamim 29 , Reference Ahmed, Farooq and Jadoon 32 , Reference Mohsin, Shaikh and Shaikh 35 ). Other sources included women’s magazines in Ahmed et al. and extra-familial elders in Premji et al.( Reference Ahmed, Farooq and Jadoon 32 , Reference Premji, Khowaja and Meherali 37 ).

Factors associated with complementary feeding practices

We identified several factors influencing CFP. They are summarized in Table 5 as either a barrier or a promoter, and sub-categorized as acting at family or organizational level. Overall, eight promoters and fourteen barriers were identified.

Table 5 Factors influencing complementary feeding (CF) practices in Pakistan

NGO, non-governmental organization.

Promoters

Five studies identified four promoters at the family level. Promoters were: more educated mothers (four studies); literate mothers (one study); mother who had more than four antenatal visits (one study); and high level of parenting support (one study).

The most commonly mentioned promoter was ‘more educated mothers’, identified in four studies( Reference Liaqat, Rizvi and Qayyum 13 , Reference Hazir, Senarath and Agho 15 , Reference Shamim 29 , Reference Memon, Shaikh and Kousar 36 ). A positive relationship between maternal education and nutritional status was described by Liaqat et al. (WOE=M)( Reference Liaqat, Rizvi and Qayyum 13 ), with Shamim (WOE=M) noting that some uneducated mothers delayed CF until their child was 1 year old( Reference Shamim 29 ). Interestingly, while Memon (WOE=H) et al. noted that the probability of inappropriate CFP in uneducated mothers was 3·7 times higher than in educated mothers, there was no correlation between paternal education and CFP( Reference Memon, Shaikh and Kousar 36 ).

Five studies identified four promoters at the organizational level. Promoters were: wealthy households (three studies); activity of non-governmental organization (one study); improved health education (one study); and urban households (one study).

The most identified promoter was wealthier households. Hazir et al. (WOE=H) found that the percentage of timely CF at 6–8 months was higher in richer and richest households, at 51·3 and 70·9 %, respectively, compared with poorest, poorer and middle households, which achieved rates of 28·0, 33·7 and 23·1 %, respectively( Reference Hazir, Senarath and Agho 15 ). This association was also found in Senarath et al. (WOE=H) and Lingam et al. (WOE=H)( Reference Senarath, Agho and Akram 16 , Reference Lingam, Gupta and Zafar 31 ).

Barriers

Twelve studies identified ten barriers at the family level. Barriers were: lack of maternal knowledge on CF (five studies); cultural beliefs (four studies); higher parity of mother (three studies); insufficient breast milk (three studies); lack of maternal time (two studies); mother in employment (two studies); mother becomes pregnant during CF period (two studies); mother who had fewer than four antenatal visits (one study); delivery by caesarean section (one study); and difficulty getting the baby to feed (one study).

The most cited family-level barriers were lack of maternal knowledge on CF and cultural beliefs. In terms of inadequate knowledge, Memon et al. (WOE=H) found that 90 % of mothers had inadequate knowledge on frequency of CF( Reference Memon, Shaikh and Kousar 36 ), with large gaps in knowledge also reported by Mohsin et al. (WOE=H)( Reference Mohsin, Shaikh and Shaikh 35 ). Knowledge is not sufficient for good CF, however; Mehkari et al. (WOE=H) reported that although 78 % of female health-care professionals knew WHO guidelines on initiating CF at 6 months, only 53 % adhered to them( Reference Mehkari, Zehra and Yasin 27 ). Regarding cultural beliefs, ideas about certain foods being ‘hot’ or ‘cold’ inhibited dietary diversity. Mohsin et al. (WOE=H) listed ‘hot’ foods including bread, meat, potato and egg, and ‘cold’ foods including rice, curd and banana, and observed that 41 % of caregivers would avoid ‘cold’ foods in winter and during illness( Reference Mohsin, Shaikh and Shaikh 35 ). Premji et al. (WOE=M) also found that cultural beliefs inhibit CF during illness( Reference Premji, Khowaja and Meherali 37 ).

In total, nine studies identified four barriers at the organizational level. Barriers were: household poverty (six studies); food affordability and access (four studies); poor advice from health workers (one study); and rural households (one study).

The barrier posed by being poor was the most popular influencing factor either positively or negatively. Hazir et al. (WOE=H) and Senarath (WOE=H) both identified that CF initiation was delayed significantly in the middle to poorest wealth index compared with the richest in Pakistan( Reference Hazir, Senarath and Agho 15 , Reference Senarath, Agho and Akram 16 ). Dykes et al. (WOE=M) described how women felt that poverty stopped them being able to adequately feed their children( Reference Dykes, Lhussier and Bangash 33 ), and Liaqat et al. (WOE=M) named poverty as one of the main reasons for inappropriate practices( Reference Liaqat, Rizvi and Qayyum 13 ). Cost and accessibility was the second most identified barrier, with Shamim (WOE=M) finding that meat and seasonal fruits were rarely given due to their cost and low availability, and Shamim et al. (WOE=M) observing that expensive ready-to-make cereals were often overdiluted( Reference Shamim 29 , Reference Shamim, Naz and Waseem Jamalvi 30 ).

Discussion

To our knowledge, the present is the first systematic review to assess CFP in Pakistan. We identified that CFP in many Pakistani SA families were not meeting WHO IYCF standards on minimum dietary diversity, meal frequency and timing of introducing CF.

Implications of key findings

Grains, roots, tubers and legumes appear to predominate for CF in Pakistan. It is concerning that only five of nine studies discussing dietary diversity described CF foods covering four of the seven groups recommended in the WHO IYCF guidelines; the true number of infants consuming foods across these four groups is likely to be low. No study directly addressed rates of meeting MDD requirements. Inappropriate CF foods were sometimes described, such as tea and crackers mentioned by Sarwar (WOE=H) and Shamim et al. (WOE=M)( Reference Sarwar 28 , Reference Shamim, Naz and Waseem Jamalvi 30 ). Besides reducing appetite, tea tannin impairs Fe absorption which may contribute to anaemia( Reference Zijp, Korver and Tijburg 38 ). The widespread use of commercial complementary food items in Pakistan due to doctors’ recommendation, perceptions that this is ‘best for the baby’, media influence and easy availability of such foods is another issue which must be tackled( Reference Mohsin, Shaikh and Shaikh 35 ). Only two studies provided information on CF related hygiene, which both discussed hand-washing( Reference Mehkari, Zehra and Yasin 27 , Reference Mohsin, Shaikh and Shaikh 35 ). Food hygiene is an emerging concern in Pakistan and we recommend future studies collect data on this important topic( Reference Akhtar 39 ).

In terms of MMF, even when CF is initiated it is often not given at the optimum rate of three or four times daily. Increased presence of non-governmental organizations and medical staff in local factories may help improve CF practices; Dev et al. (WOE=H) examined CF in two socio-economically similar colonies in Karachi and linked the superior CF practices in Bilal Colony, where 48·3 % met MMF compared with 35·7 % in Bhains Colony, to these factors( Reference Dev, Shaikh and Shaikh 34 ). This approach could help inform interventions to improve MMF in other areas.

Timing of CF is a problem in Pakistan, which has the lowest proportion of timely CF among all the SA countries( Reference Senarath, Agho and Akram 16 ). Premature CF is associated with increased risk of infection according to Shamim et al. (WOE=M)( Reference Shamim, Naz and Waseem Jamalvi 30 ), and Sarwar (WOE=H) found late introduction of CF affected growth and could lead to defiant eating behaviours including rejection of food and difficulty in learning to masticate( Reference Sarwar 28 ). Measures to increase knowledge about timing of CF can help mitigate these health effects.

The eight promoters identified in the present review can help inform interventions to improve CF in Pakistan. One in particular, improved health education, could help address some familial barriers such as a lack of knowledge or cultural beliefs. Sarwar (WOE=H) found that mothers wanted information in traditional languages to help improve their care practices, and also valued group discussions and demonstrations( Reference Sarwar 28 ). It was thought that such sessions, by being more interactive, could address points of confusion. Another health-care intervention, cognitive behavioural therapy, has been trialled to target deeply embedded beliefs around breast-feeding in a socio-economically disadvantaged district of Pakistan( Reference Rahman, Haq and Sikander 40 ). By building a therapeutic relationship with the mother, this holistic intervention was used successfully to deliver messages on breast-feeding. Active methods to encourage mothers to practise correct CF behaviour could be very effective, and should be practical while respecting the local customs and traditional culture( Reference Sarwar 28 ).

Fourteen separate barriers to appropriate CF were identified. Among the familial barriers, the listing of ‘mother in employment’ as a barrier is concerning and suggests that more needs to be done to support working mothers. Memon et al. (WOE=H) suggest workplace policies should be modified to provide social support and motivation for breast-feeding among working mothers( Reference Memon, Shaikh and Kousar 36 ). A further very notable barrier is the absence of knowledge on appropriate CF at all levels. Previous studies have shown that educational and behaviour change interventions successfully improve CF practices( Reference Imdad, Yakoob and Bhutta 41 , Reference Shi and Zhang 42 ). Training should be provided in order for health-care professionals to deliver consistent information, as properly trained professionals can improve feeding practices and outcomes in children aged 6–24 months( Reference Zaman, Ashraf and Martines 43 ). Given that eight of the nine studies that discussed advice providers highlighted the importance of family and friends, it seems advisable that interventions should target whole communities, not mothers alone.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of our systematic review are derived from searching a large number of databases utilizing very broad search strings, performing an updated search in June 2016, and having two reviewers undertake study selection, data extraction and quality assessment.

Key limitations include the exclusion of: (i) papers that focused solely on children over 2 years of age, where CFP described in their younger years may have been missed; (ii) papers published before the year 2000 at full-text review; and (iii) papers not published in English, which would have added to the diversity of CFP described. These limitations mean the review is potentially not exhaustive; however, we were able to screen a total of 45 712 abstracts across the four reviews. This is, to our knowledge, the most comprehensive review of the literature to date.

In several studies where there was overlap between children under and over 2 years of age and/or SA by Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi origin, CFP described and attributed to the whole study population may be incorrect. Furthermore, we did not assess the quantities of the foods used, only the frequency with which they appeared in the studies.

While we excluded interventional studies that may have described CFP in their study population, this is unlikely to be the primary focus of such studies and therefore unlikely to have affected our systematic review significantly.

Conclusion

Despite adoption of the WHO IYCF guidelines, inadequate CFP remain in families across Pakistan. While Pakistan has made giant strides in decreasing child mortality over the last two decades, further work is required to improve CFP to reduce this further, as well as to tackle rates of wasting, stunting and underweight. The current systematic review has highlighted CFP and the factors that influence them, paving the way for development of evidence-based interventions.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank Lucy Stephenson, Alexandra Robinson, Melanie Flury, Taimur Shafi, Atul Singhal, Rani Chowdhary, Charlotte Hamlyn-Williams, Prerna Bhasin, Aaron O’Callaghan and Conor Fee for assisting in the systematic review. Financial support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. L.M. is funded by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Doctoral Research Fellowship (grant number DRF-2014-07-005); S.A. is funded by the NIHR Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) North Thames at Bart’s Health NHS Trust; and M.L. is partly supported by the NIHR CLAHRC North Thames at Bart’s Health NHS Trust. NIHR had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest. Authorship: L.M., R.L. and M.L. conceived and participated in the design of the study. L.M., A.S., A.D., E.C.A., J.Y.K., A.P. and S.A. coordinated and undertook the review. All authors performed the data interpretation and contributed equally to write the draft, read and approved the final manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: Not applicable.